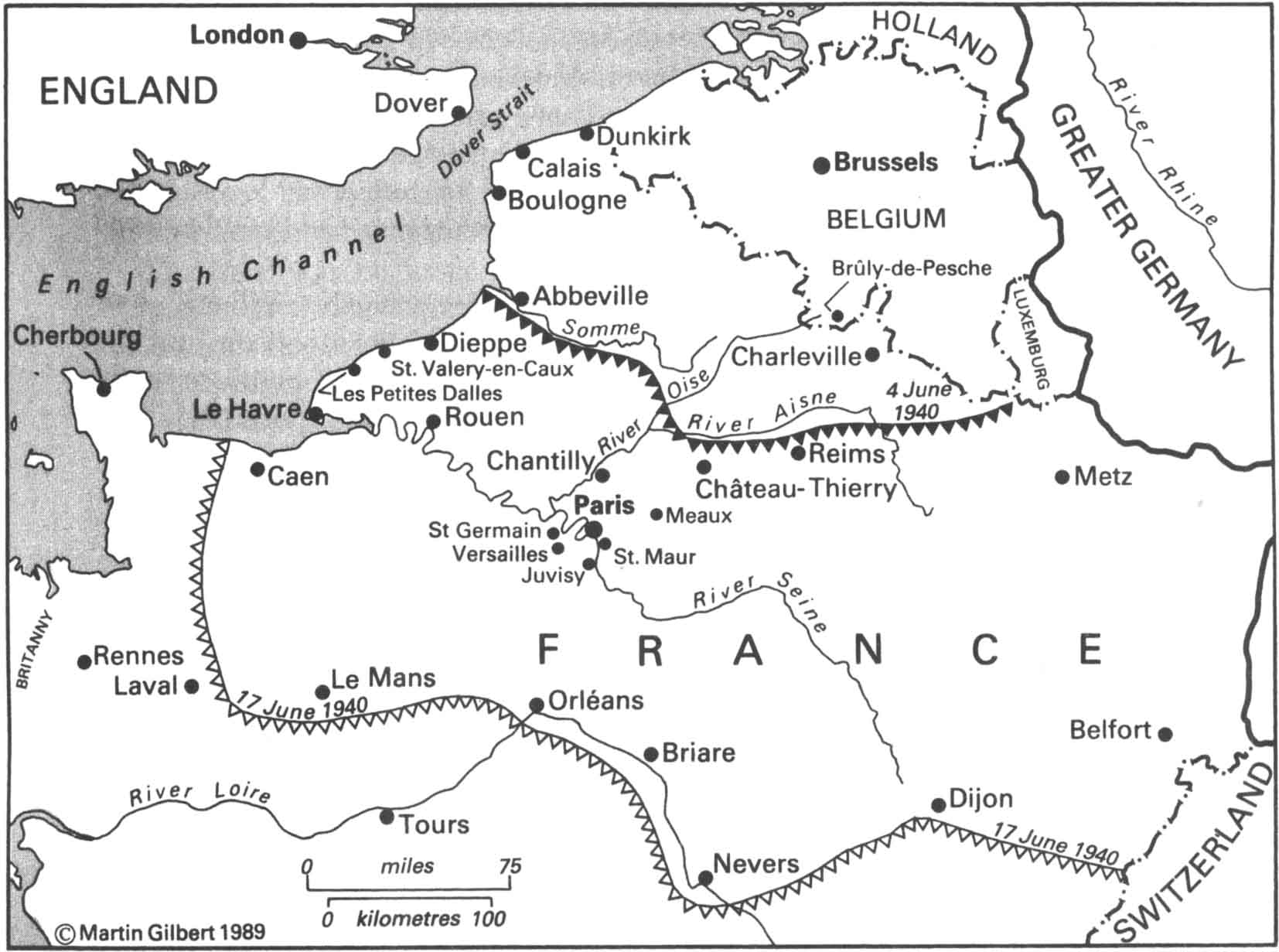

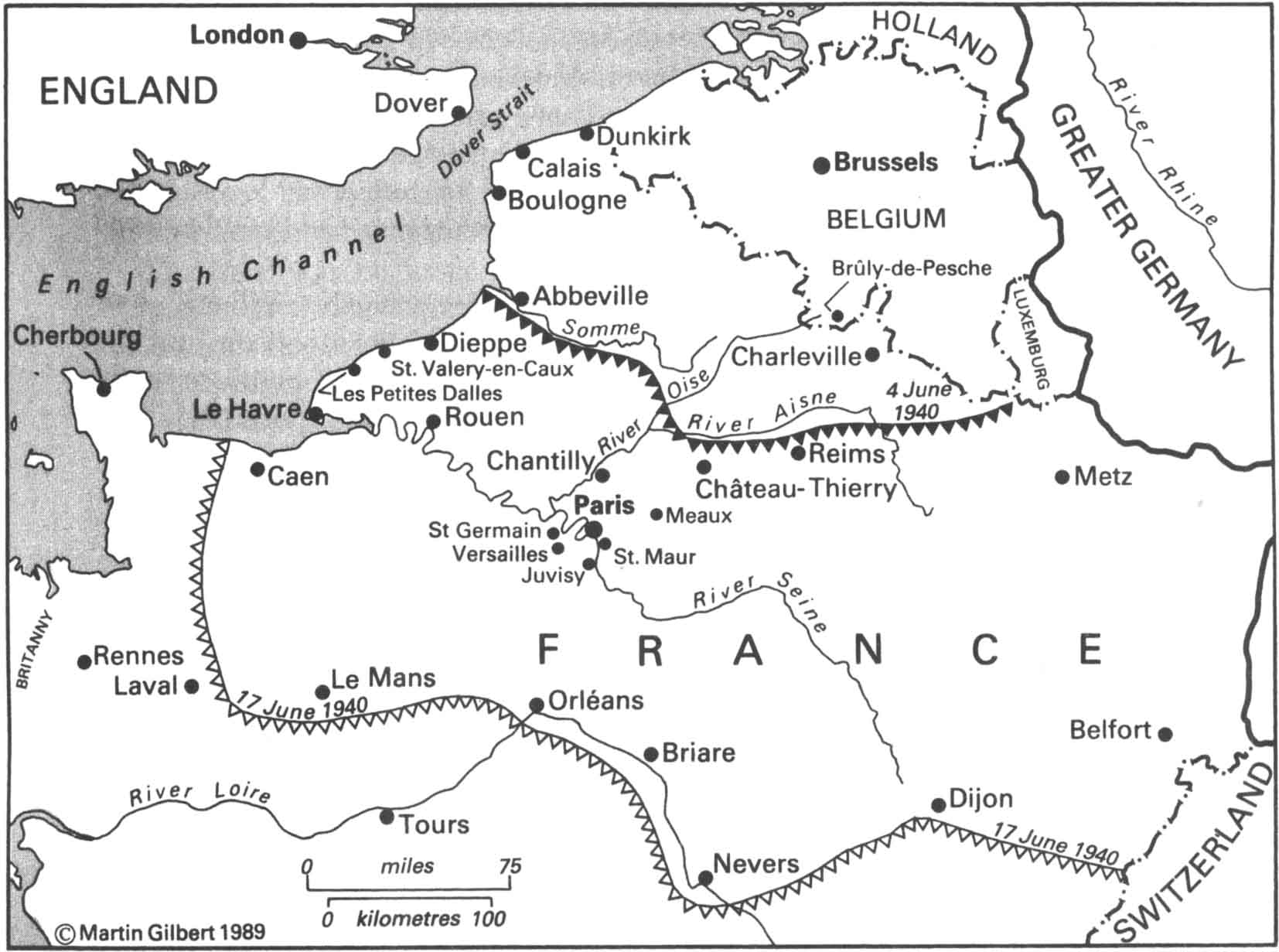

The battle for France, June 1940

With his forces in the Dunkirk perimeter about to be liberated to join the move south, Hitler began the most ambitious step of the war so far, to achieve what the Kaiser had failed to achieve during four unremitting years of battle between 1914 and 1918, the capture of Paris. ‘Ordered to the Führer today’, General Rommel wrote to his wife on 2 June 1940. ‘We’re all in splendid form’.

On June 3 the German Air Force bombed Paris. In all, 254 people were killed, 195 of them civilians, the rest soldiers. Among the civilian dead were many schoolchildren who had taken refuge in a truck which had received a direct hit. It was only under threat of severe penalties that Georges Mandel, the Minister of the Interior, was able to prevent a flight of public officials from the capital. In Berlin, Admiral Fricke, Chief of the Operations Department of the German Navy, circulated a memorandum on post-war strategy. All the peoples in the German-occupied countries in the West—Norway, Denmark, Holland, Belgium and France—should be made ‘politically, economically and militarily fully dependent on Germany’. As for France, she should be so militarily and economically destroyed, and her population so reduced, that she could never rise again to encourage the smaller states.

German confidence was easy to understand. But on June 3 the British War Cabinet was told that the Norwegian King, Haakon, although preparing to leave Norway for exile in England, ‘believed that the Allies would win in the end’.

On June 4 the British took stock of their ability to combat an invasion force, should France fall and the full German strength be turned, at last, across the English Channel. There were only five hundred heavy guns on British soil, some of them museum pieces. On June 4 the War Cabinet learned that, between May 19 and 1 June, 453 aircraft of all types had been produced; in that same period, 436 had been lost. Thirty-nine Spitfires had been produced and seventy-five lost. The number of aircraft actually serviceable on June 2 was 504. If the Germans were to mount an air attack on Britain, the head of Fighter Command, Sir Hugh Dowding, had told the War Cabinet on June 2, ‘he could not guarantee air superiority for more than forty-eight hours’. Dowding, incidentally, was not one of those who, at that time, knew of the Enigma decrypts which made it clear that an invasion would not take place at least until after France’s defeat.

Nevertheless, the British had been forced to leave a vast armament behind in the Dunkirk perimeter: 475 tanks and 38,000 vehicles; 12,000 motorcycles; 8,000 field telephones and 1,855 field wireless sets; 400 anti-tank guns, 1,000 heavy guns, 8,000 bren guns and 90,000 rifles, together with a staggering 7,000 tons of ammunition. There were now less than 600,000 rifles and 12,000 bren guns in Britain. The losses would take between three and six months to make good.

On the afternoon of June 4, Churchill spoke in the House of Commons, telling Members of Parliament, who were elated by the Dunkirk evacuation but understandably fearful for the future: ‘Even though large tracts of Europe and many old and famous States have fallen or may fall into the grip of the Gestapo and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be’.

Addressing himself to the millions of Britons who did not see how Britain could resist a German invasion, Churchill declared: ‘We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, and even if, which I do not for a moment believe, this island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving, then our Empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, would carry on the struggle, until, in God’s good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the Old’.

Churchill’s words gave courage to his fellow countrymen; in their hours of doubt and anxiety he had told them ‘we shall never surrender’. Those who heard him speak felt themselves stronger, able to face the future with a sense of national unity and pride. ‘We shall fight in France…’; these five words were not a vague promise but an immediate reality; 224,318 British troops had been evacuated from Dunkirk, but 136,000 still remained in Western France, ready to be thrown into the battle. Yet more were on their way from Norway; the first 4,500 Allied troops had been successfully evacuated from Narvik on the night of June 3. There were also 200,000 Polish soldiers in France, the remnants of the Polish Army which had confronted the Germans nine months earlier in Poland, and who had managed to escape through Roumania.

On the evening of June 4, Hitler, having moved his headquarters to a village on Belgian soil, Brûly-de-Pesche, near the border with France, ordered 143 German divisions to advance along a 140-mile front. Facing them were sixty-five French divisions. At four in the morning of June 5 the battle was begun. As German forces now opened their southward attack with a fierce aerial and artillery bombardment along the line of the Somme and the Aisne, General Weygand issued an appeal to the French troops who would have to meet the onslaught. ‘Let the thought of our country’s sufferings inspire in you the firm resolve to resist,’ it read. ‘The fate of the nation and the future of our children depend on your determination.’ That day, searching for the ablest of the soldiers to help direct the battle, Paul Reynaud appointed the recently promoted General de Gaulle to be Under-Secretary of State for War.

British troops were also in action on June 5, holding the line on the French right flank, between Abbeville and the sea. These troops, ‘though they fought with dogged tenacity’, noted the British Official History, were forced back and then virtually overwhelmed as a result of their mounting casualties, dwindling ammunition, and ‘the superior numbers of the enemy’. Such, despite innumerable heroic actions, was the fate of the whole Allied line.

That day, over the front line north of Chantilly, one of Germany’s most successful fighter pilots, Werner Molders, was forced to bail out of his burning Messerschmitt. Parachuting to earth, he found that he was on the German side of the front. Returning at once to action, he was to end the year with sixty-eight French and British ‘kills’ to his credit, becoming the first German pilot to receive the coveted Knight’s Cross with each of its three enhancements, Oak Leaves, Swords and, most rarely awarded of all, Diamonds.

In London, now that the Enigma decrypts had been accurately understood, and with imminent invasion no longer a possibility, Churchill decided to make available to Reynaud for the battle in France two squadrons of fighters and four squadrons of bombers. Churchill also agreed to Reynaud’s request for more British troops to be sent to France; the 52nd Division would begin its southward crossing of the Channel on the following day. Churchill also wanted immediate action against the German forces already holding parts of the Channel coast, asking his military experts to prepare enterprises ‘with specially trained troops of the hunter class, who can develop a reign of terror down these coasts’, even landing tanks ashore in France which could ‘do a deep raid inland, cutting a vital communication, and then crawl back, leaving a trail of German corpses behind them’.

The battle for France, June 1940

The ‘best’ German troops, Churchill argued, would be attacking Paris, leaving the ‘ordinary German troops of the line’ along the Channel coast between the Somme and Dunkirk. The lives of these troops, he wrote, ‘must be made an intense torment’.

On June 6 the Germans broke through the French defences at several points. The scent of a total German victory was in the air. ‘After the war,’ Goebbels wrote in triumph in his diary that day, ‘we shall deal quickly with the Jews.’ On the following day, King Haakon of Norway and his Government embarked at Tromsö on board the British cruiser Devonshire, bound for London. Before he left, the king broadcast to the Norwegian people, informing them that all military operations were at an end; the 6th Division had been forced to capitulate, and the Chief of Defence, General Otto Ruge, had been taken prisoner. ‘When the orders became known,’ Colonel Munthe-Kaas later wrote, ‘it was as though the units had been paralysed. Profound grief and anger filled men’s minds. Some wept. All the fighting, all the tough endurance, all the victorious combats had been of no avail.’ ‘All our hopes had collapsed,’ one young Norwegian soldier later recalled, ‘and the people felt that they had been deserted by their leaders and their Allies.’

Elsewhere, those Allies were engaged in yet another struggle, similarly outnumbered. In order to try to hamper British air support for France, on June 5, and again on June 6, the Germans had sent about a hundred bombers over Britain. But the British Government, encouraged to do so by Churchill, substantially increased its air support to France on June 6, and again on June 7, contributing on the 6th a total of 144 fighters to the air battle over France, the equivalent of twelve squadrons, and carrying out that day more than a hundred bomber sorties on targets indicated by the French High Command. Two additional fighter squadrons would be sent to France on June 8, as well as twenty-four complete barrage balloon outfits, together with their crews, for the defence of Paris.

As the Germans advanced, so their elation increased. ‘As we drove along the main Dieppe—Paris road,’ Rommel recalled on June 7, ‘we passed a German tankman bringing in a French tractor with a tank trailing behind it. The young soldier’s face was radiant, full of joy at his success.’ Rommel himself was also in buoyant mood. ‘Prisoners and booty for that day’, he wrote, ‘were tremendous and mounting hourly. Our losses were insignificant.’ But on June 8, alarmed by the ‘extremely strong resistance’ being offered by the French north of Paris, Hitler issued his Directive No. 14, effectively halting the advance in the Château-Thierry—Metz—Belfort triangle, and switching to the Paris front the troops which he had hoped to use to overrun eastern France.

In Norway, on June 8, the British evacuation of Narvik had reached its completion. During the last British naval efforts, the aircraft carrier Glorious and two destroyers, Ardent and Acasta, were sunk, and 1,515 officers and men were drowned. Only forty-three survived; forty from Glorious, two from Ardent and one, Able Seaman Carter, from Acasta. But with the successful evacuation that day of the last of the 25,000 troops who had been ashore, a sense of relief was mingled with the sense of loss.

Going down with the Glorious were the aircraft of two complete squadrons, with all but two of their pilots. That same day, June 8, Paul Reynaud pleaded with Churchill to send two or even three more squadrons to France, to join the five British squadrons already stationed there. But when the War Cabinet met that afternoon, they learned that two of those five squadrons, in action that very day, had lost ten of their eighteen aircraft. Churchill now tried to weigh up Reynaud’s request. ‘We could regard the present battle as decisive for France and ourselves,’ he said, ‘and throw in the whole of our fighter resources in an attempt to save the situation, and bring about victory. If we failed, we should then have to surrender.’ Alternatively, Churchill told his War Cabinet colleagues, ‘we should recognize that whereas the present land battle was of great importance, it would not be decisive one way or the other for Great Britain. If it were lost, and France was forced to submit, we could continue the struggle with good hopes of ultimate victory, provided we ensured that our fighter defences in this country were not impaired; but if we cast away our defence the war would be lost, even if the front in France were stabilized, since Germany would be free to turn her air force against this country, and would have us at her mercy’.

The issue was no longer one of balancing home and continental needs or forces; it was now a question of survival. ‘One thing was certain,’ Churchill told his colleagues, ‘if this country were defeated, the war would be lost for France no less than for ourselves, whereas provided we were strong ourselves, we could win the war, and, in so doing, restore France to her position.’

The War Cabinet were unanimous in accepting the logic of Churchill’s argument. No more fighters would be sent to France. And on the following day, June 9, as German troops swept towards Rouen, more than 11,000 British and French troops were assembled at the Channel port of Le Havre, to be evacuated to Britain. Other French troops, cut off entirely from the main body of the French Army, fell back on St Valery-en-Caux. There, on June 10, the British 51st Division, under General Fortune, was fighting a desperate action against far larger German forces. The French commander, General Ihler, urged Fortune to join him in the surrender of their respective armies, but Fortune refused to do so. At one moment, as British troops of the Gordon Highlanders were about to open fire on German tanks advancing towards them, French troops carrying white flags of surrender marched directly across the Highlanders’ front, making it impossible for them to open fire.

Throughout June 10 the evacuations by sea continued, from Le Havre, from Cherbourg and from St Valery-en-Caux itself. Further east, the French had been driven back across the Seine, and were retreating amid much disorder towards the Loire. Reynaud suggested that day that there should be a final stand in Brittany; he was supported in this idea by de Gaulle. But Weygand had come to the conclusion that defeat was imminent, and wanted his forces to surrender.

That afternoon, as if to indicate how close France must be to defeat, Mussolini declared war not only on France, but on Britain. Commented Hitler: ‘First they were too cowardly to take part. Now they are in a hurry so that they can share in the spoils.’

In London, all Italians between the ages of sixteen and seventy who had lived in England for less than twenty years were rounded up and interned, 4,100 in all, among them many managers, chefs and waiters from the principal London hotels and restaurants. In Washington, Roosevelt broadcast to the American people: ‘On this tenth day of June 1940, the hand that held the dagger has struck it into the back of its neighbour.’ Roosevelt also made a pledge to both France and Britain: ‘We will extend’, he said, ‘to the opponents of force, the material resources of this nation. We will not slow down or detour. Signs and signals call for speed: full speed ahead.’

Alas for Britain and France, it was the Germans who were the only ones going full speed ahead. ‘The sight of the sea with the cliffs on either side’, wrote Rommel of his arrival on June 10 at Les Petites Dalles, on the Channel coast, ‘thrilled and stirred every man of us; also the thought that we had reached the coast of France. We climbed out of our vehicles and walked down the shingle beach to the water’s edge until the water lapped over our boots.’

For the British, evacuation had once again come to dominate their naval activity. On June 10, Lieutenant-Commander Peter Scott, son of the Arctic explorer Robert Falcon Scott, who had died in his attempt to reach the South Pole in 1912, brought the destroyer HMS Broke into St Valery-en-Caux to take off as many of the men of the 51st Division as he could. Going ashore, with only three quarters of an hour before he would have to lift anchor, he was able to assemble 120 soldiers, 95 of them wounded, and embark them safely.

***

The declarations of war by Italy opened up vast new war zones. In East Africa, Italy was sovereign in Eritrea, and ruler by conquest of Ethiopia. Britain was Italy’s African neighbour in both British Somaliland and British East Africa. In North Africa, Italy was sovereign in Libya, its border with Egypt less than 450 miles from the Suez Canal, Britain’s vital imperial waterway. On June 11, as if to show that their declaration of war on Britain was in earnest, the Italian Air Force bombed Port Sudan and Aden. Also during June 11, the Italian Air Force carried out eight separate raids on the British island of Malta, in the Mediterranean.

The British and French governments, alerted by their Intelligence services more than a week earlier as to Italy’s likely declaration of war, had made plans on June 3 to bomb military targets in Italy as soon as war had broken out. On the night of June 11, from their bases in England, British bombers flew across France to bomb their targets in Genoa and Turin. From British East Africa, a small bombing raid was also carried out on Italian military installation in Eritrea. The war had come to Africa. It had also come to the Pacific Ocean. Within forty-eight hours of Italy’s declaration of war, not only on Britain and France, but on their Empires, the Australian armed merchant cruiser Manoora, steaming near the island of Nauru, sighted and gave chase to an Italian merchant vessel, the Romolo. The Romolo, unable to defend herself, and unwilling to surrender, scuttled herself instead.

Not Africa, however, nor the Pacific, but France, was the fulcrum of war on June 11, as German forces occupied Reims, and the French Government left Paris, heading southward towards the Loire. That afternoon, Churchill flew across the Channel to try to find out for himself what France intended to do; he found the Government at Briare, on the River Loire. There, he learned from General Georges of the enormous scale of French losses since the renewed German offensive had begun on June 5. Of the 103 Allied divisions in the line, 35 had been lost in their entirety. Other divisions had been reduced ‘to two battalions and a few guns’. The existing line, such as it was, ‘was held by nothing more than a light screen of weak and weary divisions, with no reserves behind them’.

Churchill urged the French to make Paris a fortress, to fight in every street. A great city, he said, if stubbornly defended, ‘absorbed immense armies’. At this, a British eye-witness noted, ‘the French perceptibly froze’. To make Paris ‘a city of ruins’, replied Marshal Pétain, ‘will not affect the issue’. The French troops, said Reynaud, ‘were worn out through lack of sleep and shattered by the action of the enemy bombers. There was no hope of relief anywhere.’

Once more, Reynaud appealed for extra British air support. But once more Churchill reiterated that none was available. To send more fighter squadrons to France, where between six and eight British squadrons were already taking part each day in the battle over France, might, Churchill said, ‘destroy the last hope the Allies had of breaking the back of Germany’s might’. Although the collapse of France opened up ‘the most distressing picture’, Churchill added, ‘yet he felt certain that even then Germany could at last be brought to her knees’.

Despite a brief discussion of a plan to hold Brittany, which a number of French generals, including de Gaulle, were prepared to examine, it was clear that the resources for a successful military resistance were almost totally used up. Churchill now spoke of the day when France would herself be under German occupation, telling Reynaud and his colleagues: ‘It is possible that the Nazis may dominate Europe, but it will be a Europe in revolt, and in the end it is certain that a regime whose victories are in the main due to its machines will one day collapse. Machines will beat machines.’

This long-term prospect could give no comfort to the French. That night, as Churchill prepared to go to bed at Briare, Marshal Pétain informed Reynaud ‘that it would be necessary to seek an armistice’.

‘Machines will beat machines’: Churchill’s words were not mere wishful thinking. That same night, as he slept in France, the first American military supplies for Britain and France were being loaded on board ship at the United States Army docks at Raritan, New Jersey. Six hundred railway freight cars had brought their precious cargoes to the dockside; these were the supplies authorized by Roosevelt ten days earlier, including 900 field guns and 80,000 machine guns. There were also half a million rifles, manufactured in 1917 and 1918, and stored since then in grease, together with 250 rounds of ammunition each. In London, before leaving for France, Churchill had approved a munitions programme whereby five hundred to six hundred heavy tanks would be ready for action by the end of March 1941.

That same June 11, far from the débâcle in France, the Norwegian army was finally demobilized and, having been disarmed, its soldiers returned to their homes. Some, determined to join the Allies, managed to leave Norway on the last of the British warships to sail westward back across the North Sea, or across the border to Sweden. One of them, Theodor Broch, Mayor of ill-fated Narvik, has recalled: ‘It was a harsh land we had had, but never had it been so delightful, so desirable as now. Our leading men had already been driven abroad. Our ships had sunk or sailed away. All along the border were young men like myself. Thousands more would follow. We had to leave to learn the one craft we had neglected. We had built good homes in the mountains, but we had neglected to fence them properly.’ Broch added: ‘Now strangers had taken over our land. They would loot it and pluck it clean before we returned. But the country itself they could not spoil. The sea and the fjords and the mountains—to these we alone could give life. We were coming back. The mountains would wait for us.’

***

The morning of June 12 saw yet another setback for the Allied cause; at St Valery-en-Caux, on the Channel coast, 46,000 French and British troops under General Ihler, including the 8,000 British troops under General Fortune, surrendered to Rommel. German artillery, firing directly on to the beaches, had prevented more than 3,321 British and French troops from being evacuated by sea; there was to be no second Dunkirk. ‘No less than twelve generals were brought in as prisoners,’ Rommel later wrote, ‘among them four divisional commanders’. A German Air Force lieutenant, who until an hour earlier had been a prisoner-of-war, was put in charge of guarding the captured generals and their staffs. ‘He was visibly delighted,’ Rommel wrote, ‘by the change of role.’

That evening, General Weygand telephoned to the French Military Governor of Paris, General Hering, ordering him to declare Paris an open city. The French capital would not, as Churchill had wished, become the scene of fighting. No tanks, no barricades, no snipers would challenge the German troops when they arrived. The Germans agreed to accept this arrangement only if the French would cease all military activity along a wide belt of suburban towns. General Hering agreed. Through St Germain, through Versailles, through Juvisy, through St Maur, and through Meaux, the Germans would march unchallenged.

Seventy years had passed since the first German siege of Paris during the Franco-Prussian War, when the French capital had sent out messages and supplies by hot-air balloon. More than twenty-five years had passed since the Kaiser’s armies had swept forward as far as Meaux, but had failed, during four subsequent years of war, to reach Paris, despite advancing as far as Château-Thierry in June 1918. Now, for the third time in seventy years, Paris was in danger.

***

Britain did not intend to abandon France to her fate. As Churchill had earlier promised Reynaud, extra British troops had been ordered to France, including men evacuated from Narvik, and Canadian troops already based in Britain. On June 12, the commander-designate of these forces, General Brooke, arrived in France. Churchill, himself still at Briare, was able to inform Reynaud on June 12 that these reinforcements were already being deployed around Le Mans. At the same time, a hundred British bombers, from their bases in Britain, were attacking the German lines of communication according to targets specifically designated by the French. In addition, fifty British fighters and seventy British bombers were still operating from bases in France against the advancing German forces.

That afternoon, Churchill flew back to England. Beneath him, from 8,000 feet, he saw the port of Le Havre burning. It too was under German attack. That night it was Le Havre’s turn to be the scene of yet another evacuation; by the early hours of June 13, 2,222 British troops had been taken back safely to England, while a further 8,837 had been taken around the French coast to Cherbourg, where they prepared to return to action side by side with the French troops on the Loire. But would the French be fighting for much longer? On his return to London, Churchill had told his War Cabinet that at Briare the French Ministers ‘had been studiously polite and dignified, but it was clear that France was near the end of organized resistance’.

In a last minute effort to stiffen French resolve, Churchill returned to France on June 13. The French Government was then at Tours. It was now ‘too late’, Reynaud said, to organize a redoubt in Brittany. There was now no hope of ‘any early victory’. France had given ‘her best, her youth, her lifeblood; she can do no more’. She was entitled to enter into a separate peace with Germany.

Churchill urged Reynaud to explore one more avenue of hope, a direct appeal to Roosevelt ‘in the strongest terms’ for American participation. ‘A firm promise from America’, Churchill said, would introduce ‘a tremendous new factor’ for France. Reynaud agreed to try, and in a telegram to Roosevelt urged the United States to ‘throw the weight of American power in the scales, in order to save France, the advance guard of democracy’. In his telegram, Reynaud asked Roosevelt ‘to declare war if you can, but in any event to send us every form of help short of an expeditionary force’. If this were done, then, with ‘America’s full help, Britain and France would be able ‘to march on to victory’.

That same day, Hitler granted an exclusive interview to the Hearst Press correspondent, Karl von Wiegand, to whom he stressed Germany’s total lack of territorial designs in North or South America.

Reynaud’s determination to continue the fight, if Roosevelt’s reply were favourable, was not shared by his Cabinet colleagues. After Churchill had returned to Britain, Weygand repeated his call for an armistice. Other Ministers, led by Mandel, wanted to move the Government to French North Africa, and to carry on the fight from there. Later that day, as German troops drew even closer to Paris, the Government moved further south, to Bordeaux. There, they received Roosevelt’s reply. The American Government, it said, was doing ‘everything in its power to make available to the Allied Governments the material they so urgently require, and our efforts to do still more are being redoubled’.

This message was clearly not a declaration of war; but at least its publication might encourage the French to carry on the fight. Roosevelt was agreeable to having the message published. But the Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, was opposed. The British Government did its best to persuade Hull to change his mind. ‘It seemed to us’, Lord Halifax telegraphed to Bordeaux, to the British Ambassador to France on the morning of June 14, ‘that it would have been impossible for the President to send such a message unless he meant it to be published, and it seemed very near to the definite step of a declaration of war.’

Churchill was still hopeful that the American response would persuade the French to fight on. Were France to continue to resist, he telegraphed to Reynaud late on 13 June, an American declaration of war ‘must inevitably follow’, and with it a ‘sovereign opportunity of bringing about the world-wide oceanic and economic coalition which must be fatal to Nazi domination’.

No such coalition was yet in prospect. On June 14 it was other forces who were gathering their strength. That day the Soviet Union delivered an ultimatum to the Lithuanian Government to allow Soviet forces to occupy their country. Lithuania complied. Two days later, Latvia and Estonia suffered a similar fate. Meanwhile, Roosevelt confirmed that his telegram to Reynaud could not be published. His message reached London at dawn on June 14. The United States, noted one of Churchill’s Private Secretaries, ‘has been caught napping militarily and industrially. She may be really useful to us in a year but we are living from hour to hour.’

At the very moment Roosevelt’s depressing negative reached London, German troops were entering Paris. By half-past six on the morning of 14 June German military vehicles had reached the Place de la Concorde, and a German command post had been established in the Hôtel Crillon. Two million Parisians had already fled the city. The 700,000 who remained woke up to the sound of German loudspeakers announcing that there would be a curfew that evening starting at eight o’clock. That morning, a huge swastika flag was hung beneath the Arc de Triomphe, and promptly at 9.45, led by a military band, German soldiers of General von Kluge’s Fourth Army marched down the Champs Élysées, in deliberate imitation of the French victory march of November 1918.

An hour and a quarter later, at eleven o’clock, the Prefect of the Paris Police, Roger Langeron, was summoned to the German Commandant and ordered to hand over the police files on all those who were politically active. To the Commandant’s anger, Langeron explained that these files had already been removed from Paris.

The German celebrations continued. So too did the establishment of the Gestapo system; espionage, informers, arrests and terror. That morning, the first twenty Gestapo functionaries arrived in Paris, headed by the thirty-year-old SS Colonel, Helmut Knochen, who had earlier made a name for himself during the successful kidnapping of Major Stevens and Captain Best at the Dutch frontier the previous November.

At that moment of German triumph, a British officer, the Earl of Suffolk, together with his secretary Miss Morden and his chauffeur Fred Hards, were in France on a special mission at the request of the British Government. Their task was to find and bring back to Britain £2½ million of French industrial diamonds essential for the making of machine tools, as well as specific rare machine tools essential for the manufacture of armaments. They had also been asked to bring back to Britain the heavy water which had been manufactured in France by a group of nuclear scientists; and also to offer the scientists a safe haven in Britain.

The Earl of Suffolk’s mission was successful. On June 14, two scientists, Hans von Halban and Lew Kowarski, who had earlier moved south from Clermont Ferrand, were at Bordeaux with twenty-six cans—the world’s supply—of heavy water, an essential factor in the uranium research needed for the construction of an atomic bomb. At Bordeaux, the Earl, his chauffeur, his secretary, the scientists, the heavy water, the industrial diamonds and the machine tools were taken on board a collier, the Broompark, which was waiting for them. As they sailed for England, the ship next to them was sunk by a magnetic mine; four days later they reached the safety of Falmouth.

Others were unable to flee. That June 14, as the Germans marched through Paris in triumph, the fifty-six-year-old Austrian-born Ernst Weiss committed suicide in his Paris apartment. A novelist, a former medical officer in the Austro-Hungarian Army in the First World War, a pupil of Freud and a friend of Kafka, he was also a Jew. In March 1938, when Hitler annexed Austria, Weiss had fled from Vienna to Prague. In March 1939, when German forces entered Czechoslovakia, he had fled Prague for Paris. Now he felt that there was no more hope. A thousand miles to the east, the Germans had begun the deportation of 728 Poles, held until then in prison in Tarnow, to the new concentration camp at Auschwitz. Some had been imprisoned because they had tried to escape from the General Government southwards into Slovakia. Others had been imprisoned because they were leaders of their local communities, priests and schoolteachers. Three of these deportees were Jews, two lawyers and the director of the local Hebrew school; none of the Jews, and only 134 of the Poles were to survive the torments of the camp. As the passenger train in which they were being taken to Auschwitz passed through Cracow station, the deportees heard an excited train announcer trumpet over the loudspeaker system the fall of Paris.

As the citizens of Paris watched their German conquerors, the citizens of Rennes, in western France, were surprised to see Canadian troops hurrying through their town. They had disembarked that morning at Brest, and were intent on moving up to the front as quickly as possible. ‘Everywhere the people cheer us,’ one of their officers noted. ‘Our lads are puffed up like a load of dynamite.’ Continuing their journey by train, by nightfall they had reached Laval. As they bedded down for the night, they could see the long line of cars and carts loaded with bedding parked beside the road, or heading west towards the coast.

On June 15 German troops took Verdun, the fortress which in 1916 had withstood every German onslaught, and for whose tenacious defence Marshal Pétain had won such acclaim. In western France, the Canadian troops who had moved forward as far as Laval on 14 June, began preparations to go into action against the Germans, who were then less than twenty miles away. But on the morning of June 15 they were ordered to take the train to St Malo, on the coast, where, at five o’clock that evening they boarded a British ship, the steamship Biarritz, bound for Southampton. Their only losses: six men who had gone missing during their journey to Laval and back.

On June 15, in Bordeaux, Reynaud told the British Ambassador that, if America did not agree to come into the war ‘at a very early date’, France would be unable to continue to fight, even from French North Africa. As soon as he received Reynaud’s message, Churchill telegraphed to Roosevelt to reinforce Reynaud’s plea for an American declaration of war. ‘When I speak of the United States entering the war’, Churchill explained, ‘I am, of course, not thinking in terms of an expeditionary force, which I know is out of the question. What I have in mind is the tremendous moral effect that such an American decision could produce, not merely on France, but also in all the democratic countries in the world, and, in the opposite sense, on the German and Italian peoples’.

This telegram was sent from London to Washington at 10.45 on the evening of June 15. It was no more effective than those which had preceded it. Roosevelt had no intention of entering the war, no matter how the matter was phrased or disguised. Nor did the facts on the ground give any confidence that France could maintain the battle for much longer. Paris was lost. Verdun was lost. On June 15, of 261 British fighters sent to France in the past ten days, 75 had been shot down or destroyed on the ground by German bombers. A further 120 were unserviceable or lacked the fuel to fly back to Britain; they were burned on the French airfields on June 15 to prevent them from being captured by the Germans. Sixty-six were flown back to Britain. In ten days, the Royal Air Force had lost a quarter of its fighter strength.

On June 16 the Germans entered Dijon. As the French Cabinet met in Bordeaux to discuss the new crisis, a German Army Group, hitherto quiescent, crossed the Rhine at Colmar. At the Cabinet meeting, Pétain, as Deputy Prime Minister, called for an immediate armistice, and threatened to resign if his colleagues refused. Reynaud, in despair, asked Britain to release France from its agreement not to make a separate peace. The British Government had no choice but to agree. It did so, giving as its condition that the French Fleet ‘immediately sails for British ports’. No such promise was made. As a last resort, the British Government offered France an ‘Anglo-French Union’ which would continue to make war even if France were overrun. The two countries, joined as one, could not then be defeated unless Britain also went down. Reynaud favoured this plan. His colleagues were not enthusiastic. Thereupon Reynaud resigned.

That evening, Marshal Pétain formed a new government. Its first act, at eleven o’clock that night, was to ask the Germans for an armistice. In the late morning of June 18, at his headquarters at Brûly-de-Pesche, Hitler learned of the French Government’s request. In delight, he jerked up his knee in a jump of joy, a single, ecstatic movement which was caught by his official cameraman, Walter Frentz, but which John Grierson, a documentary producer then serving in the Canadian Army was to ‘loop’—that is, to repeat in a series of frames—so as to give the impression that Hitler was dancing.

Negotiations for an armistice began almost at once; nevertheless, Hitler took the precaution to order his troops to continue their advance in the west, to take Cherbourg and Brest, and to take Strasbourg, the city which Germany had conquered in 1871 and France regained in 1918.

Hitler’s principal concern, as the negotiations for an armistice continued throughout June 17, was that the French might still be tempted by Britain, or pushed by the severity of his own peace terms, to carry on the war in North Africa. To avert this danger, he was prepared to contemplate the survival of France as a sovereign power; in this way the legitimate Government of France would continue to be sovereign over the French colonies overseas, which otherwise might go over to a North African based government, or be seized by Britain. To ensure that a sovereign French Government would have a semblance of reality, he would have to leave it with a part of France unoccupied, under the direct rule of a French Prime Minister and Cabinet. This he was prepared to do, even though Paris would remain within the German occupied zone.

At midday on June 17, Pétain broadcast to the French people, to inform them that negotiations for an armistice were in progress. ‘Thank God, now we’re on our own’ was the comment of Tubby Mermagen, commander of a British fighter squadron. ‘He expressed the feelings of us all,’ one of Mermagen’s Flight Commanders, Douglas Bader, later recalled. That afternoon, Churchill broadcast to the British people: ‘Whatever has happened in France’, he said, ‘makes no difference to our actions and purpose. We shall do our best to be worthy of this high honour. We shall defend our Island home, and with the British Empire we shall fight on unconquerable until the curse of Hitler is lifted from the brows of mankind. We are sure that in the end all will come right.’

That night, British bombers struck at the German oil installations at Leuna, south of Leipzig, in the heart of Germany.

Throughout June 17, British troops were being evacuated from France; Operation Ariel, as the new evacuations were called, was almost on the scale of Dunkirk’s Operation Dynamo, though without its risk of an imminent assault from the land. From Cherbourg, 30,630 men were taken off; from St Malo 21,474 Canadians; from Brest, 32,584 soldiers and airmen were rescued; from St Nazaire and Nantes, 57,235; from La Pallice, 2,303 Britons and Poles, and, from a dozen ports on the southern half of the Atlantic coast of France, 19,000 troops, most of them Poles. In the eight days between June 16 and 24, all 163,225 had been taken off to safety. One boat load, however, was not so fortunate; on June 17 the passenger liner Lancastria took five thousand soldiers and civilians on board at St Nazaire. As she left the port, heading for England, a German bomber struck, and the ship was sunk. Nearly three thousand of those on board were drowned.

Churchill, on being given details of the disaster, forbade immediate publication of the news, fearing its effect on public morale. ‘I had intended to release the news a few days later,’ he was to recall after the war, ‘but events crowded upon us so black and so quickly, that I forgot to lift the ban, and it was some time before the knowledge of this horror became public.’ It was only six weeks later, after the facts were publicized in the United States, that the British Government released the news.

The British, Polish, Canadian and French troops who left France in Operation Ariel had reason to believe that their return to Britain would be followed quickly enough by a German invasion of the now vulnerable island. But Hitler had as yet no such plan. ‘With regard to the landing in Britain,’ German naval headquarters were informed on June 17 by the High Command, ‘the Führer has not yet expressed any such intention, being well aware of the difficulties involved in such an operation. Up to now, therefore, the High Command of the armed forces has not carried out any preparatory work.’

That night, as on the previous night, British bombers set off for targets in Germany, their task being to strike at ‘aircraft factories, factories making aluminium, oil-producing plants and communications’ throughout the Ruhr. But the confidence and determination which such raids showed could not mask the grave reality in France, where, in the five weeks since May 10, a total of 959 aircraft had been destroyed, and 1,192 pilots and aircrew shot down.

At noon on June 18 Hitler met Mussolini at Munich. To Mussolini’s surprise, Hitler made ‘many reservations’, as the Italian Foreign Minister, Count Ciano, noted in his diary, ‘on the desirability of demolishing the British Empire, which he considers, even today, to be an important factor in world equilibrium’. Despite Mussolini’s objections, Hitler then supported the proposals put forward by Ribbentrop, but in fact Hitler’s own, for lenient peace terms for France. ‘Hitler is now the gambler who has made the big scoop,’ Ciano wrote, ‘and would like to get up from the table, risking nothing more.’

Hitler was confident that the French will to resist was broken. At Bordeaux, the French Foreign Minister, Paul Baudouin, and the Minister of Marine, Admiral Darlan, both assured the British Ambassador that the French Fleet would be sailed to safety or scuttled rather than be allowed to fall into enemy hands. These brave words masked a lack of ability to carry them out. Equally brave, and apparently equally empty except in courage, were the words broadcast from London at six o’clock that evening by General de Gaulle. The French Government, he said, ‘alleging the defeat of our armies’, had entered into negotiations with the Germans with a view to bringing about an end to the hostilities. ‘But has the last word been said? Must we abandon all hope? Is our defeat final?—No!’

De Gaulle went on to assure his listeners ‘that the cause of France is not lost. The very factors that brought about our defeat may one day lead us to victory. For France is not alone! She is not alone! Behind her is a vast Empire, and she can make common cause with the British Empire, which commands the seas and is continuing the struggle’. Like Britain, de Gaulle added, France could also ‘draw unreservedly on the immense industrial resources of the United States’. The outcome of the struggle, de Gaulle asserted, had not been decided by the Battle of France. ‘This is a world war.’ Mistakes had been made, but the fact remained ‘that there still exists in the world everything we need to crush our enemies some day. Today we are crushed by the sheer weight of the mechanized forces hurled against us, but we can still look to a future in which even greater mechanized forces will bring us victory. Therein lies the destiny of the world.’

With this forceful echoing of Churchill’s words at Briare on June 11—‘Machines will beat machines’—de Gaulle went on to call upon all French officers ‘who are at present on British soil or may be in the future, with or without their arms’, as well as on all French engineers and skilled workmen, ‘to get in touch with me. Whatever happens, the flame of French resistance must not and shall not die.’

A forty-nine-year-old Brigadier-General in exile was challenging the authority of a Marshal of France. His words, were heard by many with respectful incredulity. Today they are inscribed on a plaque attached to the wall of the building in which he spoke them.

Throughout June 18, German forces continued their advance across France, intent upon creating a zone of occupation, not by negotiations, but by military force; by nightfall they had occupied Cherbourg. ‘There were some bad moments for us,’ Rommel wrote to his wife, ‘and the enemy was at first between twenty and forty times our superior in numbers. On top of that they had twenty to thirty-five forts ready for action, and many single batteries. However, by buckling-to quickly, we succeed in carrying out the Führer’s special order to take Cherbourg quickly.’ Other German commanders were equally successful. Also, on June 18, Vannes, Rennes, Briare, Le Mans, Nevers and Colmar were occupied.

That same day, as a trumpet call of defiance, British bombers struck at military targets in Hamburg and Bremen.

On June 19 the British began the evacuation of the Channel Islands, so close to France that they must inevitably fall to Germany once France fell. In all, 22,656 British citizens were taken off in five days. Also on June 19, as German forces entered Nantes and Brest, and approached St Nazaire, a French naval officer, Captain Ronarch, succeeded in sailing the battleship Jean Bart out of the dry dock at St Nazaire, where she was being fitted out for action, and sailing her to Casablanca, in French Morocco. That day, on the battlefield, it was thirty troops from French Morocco who suffered from the savagery of an SS unit, then in action between Dijon and Lyon; in clearing out a rearguard position, the SS refused to take any prisoners, regarding the Moroccans as racially inferior, and killing even those who offered to surrender.

***

On June 20 a French delegation, consisting of a diplomat, an Army general, an Air Force general, and an admiral travelled to Rethondes, in the forest of Compiègne, to conduct the armistice negotiations with the Germans. That same day, Hitler told Admiral Raeder that one benefit of the defeat of France would be that Germany could send all her Jews, and all the Jews of Poland, to the French island of Madagascar, in the Indian Ocean.

As the negotiators at Rethondes continued their talks on the morning of June 21, the last German troops reached their point of furthest advance. From Rennes, Rommel wrote to his wife: ‘The war has now gradually turned into a lightning tour of France. In a few days it will be over for good. The people here are relieved that it is all passing off so quietly.’ Things were not so quiet near the village of Villefranche, south of Nevers, where a platoon of the SS Death’s Head Division, in action against both French and Moroccan troops, took twenty-five white French prisoners, but no Moroccans. That day’s fighting, stated the division’s communiqué, had yielded ‘twenty-five French prisoners and forty-four dead Negroes’.

Far from the battlefield, in a sun-drenched clearing in the forest of Compiègne, 21 June saw the final humiliation of the French Government. Hitler had chosen to present its plenipotentiaries with the armistice terms in the same railway coach in which the Germans had signed the surrender at the end of the First World War, and which since then had been a proud French exhibit to the victory over Germany. Until being brought to Compiègne, from Bordeaux, the French negotiators had had no inkling of where the negotiations were to be held. Now, at half past three on the afternoon of June 21, they found themselves confronted, in the railway coach itself, by a triumphant, silent Hitler, as General Keitel read out to them the preamble to the German armistice terms. After ten minutes, Hitler left; Keitel then told the four Frenchmen that there could be no discussion, only compliance. Three-fifths of the territory of European France would be under German occupation. A French Government would be set up in the unoccupied zone, and would be responsible for the administration of the French colonial empire. The French Fleet would not be allowed to pass out of French control. All 1,538,000 French prisoners-of-war would remain under German control.

Hitler having left the scene of France’s triumph in 1918 and its humiliation now, the French negotiators continued to argue; as they did so, several members of the former Reynaud Government who had hoped to continue resistance in North Africa, including Georges Mandel, were on their way by sea to Casablanca. That same day, coming by ship from France, the President and Ministers of the Polish Government-in-exile, which had been set up in Paris after the defeat of Poland, reached Southampton; as a gesture of support, King George VI went to Paddington station in London to greet them in their new city of exile.

The armistice negotiations at Compiègne continued throughout June 22. That day, the Italian Army, advancing along the French Riviera, occupied Menton. At six o’clock that evening, General Keitel, vexed at the delays upon which the French negotiators at Compiègne were still insisting, told them: ‘If we cannot reach agreement within an hour, negotiations will be broken off, and the delegation will be conducted back to the French lines.’ The negotiators then telephoned to the French Government at Bordeaux for instructions. They were instructed to sign. At ten minutes before seven, the armistice was signed. A sixth nation had succumbed to Germany in less than nine months.

Those French ex-Ministers who had hoped to maintain a sovereign France in North Africa were told of the signature of the armistice while still on board ship on their way along the Atlantic coast to Casablanca. From the North Sea shore, the German commerce raider Pinguin sailed on June 22 for ‘Siberia’, the code name for a point in the Indian Ocean between Mauritius and Australia where she and three fellow commerce raiders could meet their supply ships for food, ammunition and fuel, while sinking British merchant ships.

Hitler, the master of Poland, Norway, Denmark, Holland, Belgium and now France, had not forgotten his determination to bring Britain to her knees. But in Churchill he had an adversary who was equally determined. ‘His Majesty’s Government believe’, Churchill declared that night, ‘that whatever happens they will be able to carry the war wherever it may lead, on the seas, in the air, and upon land, to a successful conclusion.’

Britain was trying to make clear that she intended to fight on; the very newspaper which on June 23 carried the headline ‘French Sign Armistice’ on its front page had, as its back page banner headline: ‘RAF Bomb Berlin, Sink Ships, and Set Oil Store on Fire’. That night, the first of a special volunteer group of British ‘Striking Companies’ carried out a series of hit-and-run raids on the French coast between Calais and Boulogne. They were unopposed, and returned safely.

***

At 3.30 on the morning of June 23 Hitler left his headquarters at Brûly-de-Pesche and flew to Le Bourget aerodrome outside Paris. It was to be his first and only visit to the French capital. Reaching the city at a quarter to six, he was driven quickly to the most notable sites, including the Opera, the architecture of which he had admired from afar as a student, and Napoleon’s Tomb. ‘That’, he said to his entourage after leaving the tomb, ‘was the greatest and finest moment of my life.’ He then gave orders that the remains of Napoleon’s son, the Duc de Reichstadt, which rested in Vienna, should be transferred to Paris to lie next to his father. ‘I am grateful to fate’, Hitler told one of those with him, ‘to have seen this town whose aura has always preoccupied me.’

During his tour of Paris, Hitler ordered the destruction of two First World War monuments, the statue of General Mangin, one of the victors of 1918, and the memorial to Edith Cavell, the British nurse shot in Brussels by a German firing squad in 1915. His order was carried out. Leaving Paris at half past eight that morning, he returned to the airport, ordered his pilot to circle several times over the city, and flew back to his headquarters. ‘It was the dream of my life to be permitted to see Paris,’ he told his architect friend Albert Speer. ‘I cannot say how happy I am to have that dream fulfilled today.’

Sixteen months later, recalling his visit to Paris, Hitler told General von Kluge: ‘The first newspaper-seller who recognized me stood there and gaped.’ The man had been selling copies of Le Matin. Seeing cars approach, he had rushed forward to the prospective customers, seeking to thrust the newspaper in their hands and calling out all the while, ‘Le Matin! Le Matin!’ Suddenly, seeing who was in the car, he beat a quick retreat.

Back at Brûly-de-Pesche, Hitler asked Albert Speer to draw up a decree ‘ordering full-scale resumption of work’ on the proposed new public buildings and monuments which Speer had designed for Berlin, with Hitler’s guidance. All building work had stopped on the outbreak of war in September 1939. Now it must begin again. ‘Wasn’t Paris beautiful?’ Hitler said to Speer, ‘But Berlin must be made far more beautiful. In the past I often considered whether I would not have to destroy Paris. But when we are finished in Berlin, Paris will only be a shadow. So why should we destroy it?’

The new Berlin was to be ready in 1950. This ‘accomplishment’, Hitler told Speer, would be ‘the greatest step in the preservation of our history’.