The Italian invasion of Greece, October 1940

Hitler’s failure to weaken Britain sufficiently in the air to make invasion possible ended neither the conflict between Britain and Germany, nor its savagery. On 17 September 1940, the day of Hitler’s true defeat in the skies, 77 British children, and a further 217 adults, were drowned when the ship taking them to Canada, the City of Benares, was torpedoed in mid-Atlantic. One of the children on board, the eleven-year-old Colin Ryder-Richardson, tried to rescue his nurse from drowning. ‘I just couldn’t release her when she died,’ he later recalled, ‘and others had to help me to get her out of my arms.’ The young boy later received the King’s Award for Bravery, never before awarded to one so young. The courage of several members of the crew and civilian escorts was also recognized; among them Assistant Stewart George Purvis, who rescued four children from drowning, and one of the children’s escorts, Mary Cornish, who, with forty-six adults and six children, was adrift for eight days in an open boat before being rescued.

In the war of spies, the Germans were doing badly. On September 19 their Welsh agent, Arthur Owens, who had in fact been working for the British since the outbreak of war a year earlier, began to transmit a series of reports recommending targets for German bombers. These messages had been prepared for him by British Air Ministry Intelligence. That same day the Germans parachuted in another agent, Wulf Schmidt. Arrested, interrogated, persuaded to change masters, and given the code name ‘Tate’, Schmidt was sending back his first message as a double agent within two weeks. So successful did the Germans consider Schmidt’s espionage, and his work as ‘pay master’ for their other spies—all, also, turned—that he was eventually to be awarded the Iron Cross, First Class.

There were many sources of honour; on September 21, a Canadian officer, Lieutenant J. M. S. Patton, who had had no training in bomb disposal, removed an unexploded bomb which had fallen on to a factory in Surrey. He was awarded the George Cross. His fellow Canadian, Captain D. W. Cunnington, who helped him roll the bomb on to a sledge and take it away, was awarded the George Medal. In the forty days which had passed since The Day of the Eagle, 15,000 tons of bombs had been dropped on Britain.

Britain and France were about to launch their first offensive; on September, 23 British and French forces combined to carry out Operation Menace, the seizure, meant to take place without a struggle, of the Vichy-controlled port of Dakar, as a preliminary to winning over French West Africa to the Free French cause. To the surprise of the attacking forces, the Vichy authorities not only refused to transfer their loyalty to de Gaulle, but opened fire on the British ships. The garrison at Dakar had one formidable weapon at its disposal, the battleship Richelieu, which opened fire with its fifteen-inch guns, never before fired in combat. After two British warships, the cruiser Cumberland and the old battleship Resolution, had been hit, the action was called off. To have persisted with the landing, Churchill told Roosevelt, ‘would have tied us to an undue commitment, when you think of what we have on our hands already’.

During the week ending September 26, as the Blitz had continued despite heavy German air losses, more than 1,500 British civilians had been killed, 1,300 of them in London; by the end of September, the civilian death toll for the month had climbed to 6,954.

Inside German-occupied Europe, the hardships of the population had known no abatement, and life was marked by almost daily incidents of terror. On September 19, several hundred Poles had been arrested in Warsaw and sent to forced labour, and almost certain death, some to the stone quarries of Mauthausen, others to the punishment cells of Auschwitz. On September 20, an SS officer, Philip Schmitt, had received his first fifteen Belgian prisoners at a new punishment camp, Fort Breendonk, in one of the southern suburbs of Antwerp. On September 22, in Poznan, capital of the German-annexed region of western Poland, Gauleiter Artur Greiser informed all German officials under his authority: ‘It is necessary that relations with the Poles should be ruthlessly restricted to the necessities created by service and economic regards.’ Any Germans having relations with a Pole other than those arising from the Pole’s work ‘will be placed under protective arrest’. Polish women who have sex with a member of the German community ‘may be sent to a brothel’. ‘We know’, William Shirer wrote in his diary that day in Berlin, ‘that Himmler hanged, without trial, at least one Pole for having had sexual relations with a German woman’.

The produce of Polish farms was first and foremost at the disposal of the Germans. When Polish farmers refused to hand over their contribution, the punishments were drastic. On September 30 a printed wall poster in Sochaczew informed the local inhabitants that ‘The miller Niedzinski has acted against the regulations for ensuring food supplies to the General Government, so his mill at Kuklowka near Radziejowice has been burned down.’

The isolation of Jews was also spreading, not only in Poland but elsewhere in Europe. Anti-Jewish measures had been introduced in Roumania on August 10. On August 27 Marshal Pétain’s Government had abrogated a pre-war French decree which forbade all incitements to race hatred. In Luxemburg, on September 5, the occupation authorities had introduced the German Nuremberg Laws of 1935, turning the Jews into second class citizens, and had seized all 355 Jewish-owned businesses in the Duchy. In Germany itself, the night of September 24 marked the first showing of a film, Jud Süss, in the production of which Goebbels had taken a close interest. The film, by deliberately and crudely distorting an historical episode, portrayed the Jews as doubly dangerous: first there were the physically repulsive ‘ghetto’ Jews, with their grotesque ‘Semitic’ accents, who could easily be recognized as such; then there were the far more dangerous, sophisticated ‘Court’ Jews, of whom Jew Süss was one, for whom no infamy was too great if it served them in their quest for money and power.

Suffused with hatred, this Nazi version of an historical story was shown in cinemas throughout Germany and occupied Europe, as well as at special sessions for the Hitler Youth. On September 30, Himmler personally ordered all SS men and the police to see it during the course of the winter. Even the world of film and entertainment had been dragooned to serve the cause of race hatred.

One element of the Nazi policy of terror and murder was economic; the homes, the businesses, the property and even the personal belongings of the victims could all be turned to profit. On September 23, in his capacity as head of the SS, Himmler signed a decree ordering that ‘all teeth, gold fillings and bridgework should be taken out of the mouths of camp inmates’. The carrying out of the order, known as Operation Tooth, was the responsibility of SS Lieutenant-Colonel Hermann Pook. On arrival at a concentration camp, inmates were examined for dental gold. If any was found, a small tattoo was made on the left upper arm, for quick and easy identification in due course in the camp morgue. At the same time, a form was filled in giving the location of the tooth, and its estimated yield in gold. Several million such forms were captured by the Allies after the war.

The gold collected in Operation Tooth was delivered to the Reichsbank and credited to the Economic and Administrative Main Office of the SS, which also employed slave labour in stone and earth quarries, saw mills, and textile factories and throughout German-occupied Europe.

***

The British were now bombing Berlin almost every night. On September 24, William Shirer noted that the previous night’s raid had hit ‘some important factories in the north of the city, one big gas works’ and two large railway yards. Dr Goebbels, dining at the Adlon Hotel with the Spanish Foreign Minister and a host of dignitaries, had to finish the dinner in the hotel’s air raid shelter. On September 25 the raid was even heavier and longer, five hours of bombing. ‘The British ought to do this every night,’ Shirer wrote. ‘No matter if not much is destroyed. The damage last night was not great. But the psychological effect was tremendous.’

While their own capital city was being bombarded, the Germans were tightening their grip on their recent conquests. On September 25 the German ruler of Norway, Josef Terboven, after abusing those Norwegians with whom he had been negotiating to set up a Council of State, removed the existing Administrative Council from office and installed a new Government in Oslo consisting of Nazi sympathizers. Almost immediately, a ‘Norwegian Front’ was created, to serve as a broad-based underground focus of resistance. ‘The first feeling’, one Norwegian has written, ‘of resentment, grief and bitterness over the dishonourable negotiations, gave place to a liberating sense of relief. We breathed purer air because the situation had at last been clarified: resistance was the only way to go, however long and difficult that way might be.’

***

In the Far East, a further widening of the division between the confronting powers took place in the last week of September. On September 25 the United States announced a further loan to China; it would continue to support General Chiang Kai-shek in his struggle against Japan. On the following day, the United States extended the licence system for goods exported to Japan, to include all grades of iron and steel scrap. On September 27, Germany, Italy and Japan concluded a tripartite pact, extending the Rome—Berlin Axis to the Far East, lauding the creation of a New Order in Europe and Asia, and pledging each of the parties to help the others if any of them were attacked by a power not involved in the war in Europe: that is, by the United States. On October 8, Britain reopened the Burma Road for supplies to China.

***

On September 27 Jews in the occupied zone of France were ordered to carry specially marked identity cards and, if shopkeepers, to put a yellow and black poster in their window announcing ‘Jewish business’. On the following day, the works of 842 authors were withdrawn from all French bookshops, including works by Jewish writers and émigrés and French patriots. At the end of the month, the twenty-seven-year-old Theodor Dannecker reached Paris. His task was to set up a special Jewish section of the Berlin Main Security Office, reporting back directly to his superior there, Adolf Eichmann. Jews were now forced to register in alphabetical order at French police stations, where they had to give details of their domicile, nationality and profession. Henri Bergson, who was to die of old age a few months later, filled in his form: ‘Academic. Philosopher. Nobel Prize winner. Jew.’

On September 30, three German agents, two men and a woman, landed by boat off the coast of Scotland, near the tiny fishing village of Buckie. All three were caught within forty-eight hours, and brought to trial. The two men, Karl Drugge and Robert Petter, were hanged. But elsewhere, the autumn and winter of 1940 were a time of considerable German success. In October, twelve German submarines, operating in ‘wolf packs’ from the occupied zone along the French Atlantic coast, and no longer having to run the gauntlet of the North Sea and the Channel, sank thirty-two Allied merchant ships. Later they were to call this period the ‘fat year’.

On October 1, the German Army embarked upon Operation Otto, a comprehensive programme of construction and improvement on all roads and railways leading to the Soviet border. On the western bank of the River Bug, an ‘Otto Line’ was built, using Polish and Jewish forced labour. Not only were Jews brought to work on the line from several Polish cities, including Warsaw, Radom and Czestochowa, but also from cities throughout Slovakia. One camp set up as a base for work on the Otto Line was at Belzec, a Polish village on the eastern border of Greater Germany.

In October 1940, in the occupied countries of Europe, Alfred Rosenberg established a special task force to transport valuable cultural objects to Germany. More than five thousand paintings, including works by Rembrandt, Rubens, Goya, Gainsborough and Fragonard, were removed from museums and private homes, as were thousands of porcelain objects, bronzes, old coins, icons and seventeenth- and eighteenth-century furniture. At Frankfurt, Rosenberg set up the Institute for the Investigation of the Jewish Question, declaring in his opening speech: ‘Germany will regard the Jewish Question as solved only after the last Jew has left the Greater German living space.’ Meanwhile, ‘ownerless Jewish property’ could be taken at will, from hundreds of Jewish homes and shops in France, Belgium and Holland.

On October 3, the 150,000 Jews of Warsaw who lived throughout the capital were ordered to move to the predominantly Jewish district of the city, which was to be walled in, forcing more than 400,000 Jews to live in the already crowded space where 250,000 had lived before. Those Jews who had to move to this specially created ‘ghetto’ could take with them only what they could carry, or load on handcarts. The rest of their possessions, the heavy furniture, home furnishings, stoves, ovens, shop furnishings, stock, had all to be abandoned. More than 100,000 Poles, living in the area now designated a ‘ghetto’, had likewise to move, and to abandon all their possessions except those which they could carry with them.

‘Black melancholy reigned in our courtyard,’ the historian Emanuel Ringelblum, who lived in the Jewish quarter of Warsaw, wrote in his diary when details of the move to the ghetto were made public. ‘The mistress of the house’—a Polish Catholic woman—‘had been living there some thirty-seven years, and now has to leave her furniture behind. Thousands of Christian businesses are going to be ruined.’ On the following day, Jews from the suburb of Praga, across the river from Warsaw, were expelled from their homes and ordered into the new ghetto. ‘Today was a terrifying day,’ Ringelblum wrote, ‘the sight of Jews moving their old rags and bedding made a horrible impression. Though forbidden to remove their furniture, some Jews did it.’

‘The war is won!’ Hitler told Mussolini when they met at the Brenner Pass on October 4. ‘The rest is only a question of time.’ The British people were under ‘an inhuman strain’; only the hope of American and Russian aid kept them in the war. However, in spite of this boast, on the following day, unable to bear a loss of fighter aircraft, which had totalled 433 since The Day of the Eagle on August 13, Hitler ordered an end to daylight raids on Britain. October 5 saw the first of the German raids which came only at night. Hundreds of thousands of Londoners took to sleeping, for safety, in the deep stations and tunnels of the Underground; one tunnel, a mile long, between Bethnal Green and Liverpool Street station, provided shelter for 4,000 people. Hundreds of thousands of children again left London, to live in the countryside; by mid-October the number of child evacuees had reached 489,000.

On October 7, German troops entered Roumania; one more step towards Hitler’s goal of an unbroken eastern front against Russia. Five days later, he issued orders to abandon Operation Sea Lion altogether, except as a deception operation to divert the Russians’ attention from the preparations being made for war against them.

***

For the British prisoners-of-war in France, there now began a search for some means of escape. On October 10 a young subaltern, Jimmy Langley, captured at Dunkirk with severe arm and head wounds, and with his shattered left arm amputated and still suppurating, escaped from a hospital at Lille. A French family living a mile from the hospital sheltered him, giving him clothes and a night’s shelter. A few weeks later he was at Marseille, in Vichy France, and on his way back to Britain.

Langley was soon to play a leading part in guiding, from London, the dangerous work of escape, evasion and return to Britain of many hundreds of prisoners-of-war and airmen. This work went further than rescue; each returning soldier, sailor or airman brought back precious fragments of knowledge and Intelligence about the German Army, Navy and Air Force, and about civilian life in Germany and the occupied lands.

For those airmen who were shot down in aerial combat over Britain, and who had been badly burned in combat, a special burns unit at East Grinstead, headed by the New Zealand-born plastic surgeon, Archibald McIndoe, became their lifeline, as they embarked upon the slow, painful and disfiguring process of recovery, a process which, but for the dedication and skill of McIndoe and his team, would have been impossible. In five and a half years, 4,500 airmen were to be treated at East Grinstead, of whom two hundred needed a total reconstruction of face and hands.

***

On October 12, President Roosevelt spoke in Dayton, Ohio. ‘Our course is clear,’ he said. ‘Our decision is made. We will continue to pile up our defence and our armaments. We will continue to help those who resist aggression, and who now hold the aggressors far from our shores.’ At Lashio, in Burma, with the Burma Road now reopened for the despatch of supplies to China, five thousand Chinese labourers had on the previous day been loading twenty million dollars of high octane fuel, aircraft wings, rifle barrels and raw cotton on to two thousand American-built trucks. Although Roosevelt said nothing about this in his speech, it was clear that China was not to be abandoned.

Speaking of the Blitz, Roosevelt told his listeners: ‘The men and women of Britain have shown how free people defend what they know to be right. Their heroic defence will be recorded for all time. It will be perpetual proof that democracy, when put to the test, can show the stuff of which it is made.’ Hitler thought otherwise: ‘Let the British announce what they will,’ he told a visiting Italian Minister on October 14, ‘the situation in London must be horrific.’ That lunchtime, in London, a theatre company which had opened the previous day, but whose changing rooms had been bombed during the night, changed on stage for its second performance. Its repertoire was an hour-long selection of scenes from Shakespeare. ‘Shakespeare beats Hitler’ was the headline next morning in the Daily Express.

Hitler was not impressed by such bravado. In his talk with his Italian visitor on October 14 he said: ‘Let’s wait and see what London looks like two or three months from now. If I cannot invade them, at least I can destroy the whole of their industry!’ On the following night, the most intense bombing raid of the war thus far struck Londoners a ferocious blow. Nine hundred fires were started. Dozens of shelters were hit. A bomb above Balham underground station broke through to the platform below; of the six hundred people in the shelter, sixty-four were killed—buried alive under the mound of ballast and sludge which poured on to the Underground platform. From eight in the evening until five in the morning the bombs rained down. By morning, four hundred Londoners had been killed.

On the following night, October 16, British bombers struck at the German naval bases at Kiel. That day, the British Cabinet had decided that, if bad weather made it impossible to bomb specific targets, the bombers should drop their bombs on large cities such as Berlin. It was also agreed that the public should not be told of the new policy, in case people were upset that Britain’s one offensive weapon, precision bombing, was revealed to be far less effective than they had imagined.

In the United States, October 16 marked the first registration day under the Selective Training Act. On that one day, more than sixteen million Americans registered. ‘We are mobilizing our citizenship,’ Roosevelt declared in a radio address, ‘for we are calling on men and women and property and money to join in making our defence effective.’

An unexpected example of the effectiveness of American defence came on the day Roosevelt spoke, with the arrest in Boston of George Armstrong, a British merchant seaman who had deserted his ship in Boston, gone to New York, made contact with the German Consulate-General, and then returned to Boston to collect information about the Atlantic convoys. Caught before he could do any damage, in due course he was deported to Britain, where he became the first Briton of the war to be tried for spying. He was found guilty and hanged.

Armstrong’s would-be activities highlighted the perils of the Atlantic crossing for merchant seamen. On the day after his arrest, six German submarines, hunting in a ‘wolf pack’, attacked a convoy of thirty-five ships bringing war supplies from Canada to Britain. Code named SC—for Slow Convoy—7, it had sailed from Sydney, Nova Scotia. Twenty of its ships were sunk. A day later, the same six submarines attacked a second convoy, HX—coming from Halifax—79. Of its forty-nine ships, twelve were sunk. In two days, 152,000 tons of shipping had been destroyed. Among the submarine commanders whose torpedoes had done such devastating work was Günther Prien, who had sunk the Royal Oak, and Heinrich Bleichrode, whose torpedoes had sunk the City of Benares almost exactly a month earlier. On October 21, as the victorious submarines returned to their base at Lorient, on the Atlantic coast of France, German bombers made their two hundredth air raid on the port of Liverpool, one of Britain’s main gateways to the Atlantic.

It was from Liverpool that the passenger liner Empress of Britain set sail for Canada in the third week of October. Attacked from the air when 150 miles off the coast of Ireland, fifty of her crew and passengers were killed. The rest were taken off safely, and the liner towed back towards Britain. But during the journey she was torpedoed by a German submarine and sunk.

Not every German submarine could carry out its raids unchallenged; four days after the SC 7 and HX 79 sinkings, a German submarine, U-32, was forced to the surface by depth-charges. Its commander, Hans Jenisch, was the first of the German submarine aces to be captured. He and his crew were interrogated. ‘The prisoners were all fanatical Nazis,’ the British interrogator noted in his report, ‘and hated the British intensely, which had not been so evident in previous cases. They are advocates of unrestricted warfare, and are prepared to condone all aggressive violence, cruelty, breaches of treaties and other crimes as being necessary to the rise of the German race to the control of Europe.’

German successes during 1940, the interrogator added, ‘appear to have established Hitler in their minds, not merely as a God, but as their only God’.

In German-occupied Europe, the bonds of tyranny were continually tightening. On October 20, Artur Greiser told his officials in the eastern German province of the Warthegau: ‘The Pole can only be a serving element,’ and he reiterated his call ‘to firmness: be hard, and again hard’. Two days later, from the western German provinces of Baden, the Saar and the Palatinate, more than five thousand German Jews were sent by train across France to internment camps in the French Pyrenees. All the property of the deported Jews, their homes, businesses and belongings, was seized by the Germans in the towns and villages from which they were expelled, and in which their ancestors had lived for many centuries. The largest of the camps to which they were sent was at Gurs. ‘From this camp Gurs’, a German pastor, Heinrich Grüber, later recalled, ‘we had—in Berlin—very bad news, even worse news than reached us from Poland. They did not have any medicaments or any sanitary arrangements whatsoever.’

Pastor Grüber protested. For this courageous act, he was arrested and sent as a prisoner to Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

As news of the deportations, the camps and the persecution reached Britain, there was a determination not to weaken under the continuing German air bombardment, which in the week ending October 16 had killed 1,567 people, 1,388 of them in London. On October 21 Churchill broadcast to the French people: ‘We seek to beat the life and soul out of Hitler and Hitlerism. That alone, that all the time. That to the end. We do not covet anything from any nation except their respect.’ Churchill ended his broadcast with words—which a Frenchman who heard them described as drops of blood in a transfusion: ‘Good night, then: sleep to gather strength for the morning. For the morning will come. Brightly will it shine on the brave and true, kindly on all who suffer for the cause, glorious upon the tombs of heroes. Thus will shine the dawn.’

In the third week of October, Hitler left Germany for France in his special train, Amerika. On October 22 he met Pierre Laval, Deputy Prime Minister of Vichy France, at Montoire, in the German-occupied zone. Hitler was anxious that Laval should agree to a more active Vichy policy against Britain, whose defeat, Hitler said, was inevitable. Laval assured him that he desired the defeat of the country which had sullied France’s honour at Mers-el-Kebir and Dakar. On the following day, Hitler continued southward by train to the French border at Hendaye, where he met the Spanish leader, General Franco. But despite Hitler’s urgings, Franco refused to enter an alliance with Germany, or, as Hitler pressed him, to allow German troops through Spain to attack the British at Gibraltar. That attack, Hitler told Franco, could take place on January 10. After it, he would give Gibraltar to Spain. But Franco was not to be wooed; after nine hours of discussion, he still refused to cast in his lot with Germany. ‘I would rather have three or four teeth extracted’, Hitler told Mussolini, ‘than go through that again.’

Franco returned to Madrid, and Hitler to Montoire, furious that Franco had refused to join the Axis, and had denied him the means of striking at Gibraltar. At Montoire, Hitler now met Marshal Pétain, on whom he likewise pressed the need for closer collaboration between Vichy France and Germany, ‘in the most effective possible way to fight Britain in the future’. Pétain, like Franco, was evasive. Unlike Franco, he appeared to Hitler a more dignified figure, receiving praise as a man ‘who only wants the best for his own country’. But even though it might have secured the return to France of more than a million and a half French prisoners-of-war, Pétain refused to agree to enter the war against Britain, and evaded Hitler’s request that Vichy France should take steps to drive de Gaulle and the Free French forces from their bases in French Equatorial Africa.

It was from French Equatorial Africa that, on October 27, de Gaulle announced the setting up, for the Free French movement, of the Empire Defence Council. All French possessions still loyal to Vichy were invited to join it. In a powerful appeal to Frenchmen everywhere, de Gaulle declared: ‘I call to war, that is to say to combat or to sacrifice, all the men and all the women of the French territories which have rallied to me.’ In ‘close union’ with France’s Allies, that part of ‘the national patrimony’ which was in the hands of the Free French would be defended, while elsewhere the task would be ‘to attack the enemy wherever it shall be possible, to mobilize all our military, economic and moral resources, to maintain public order, and to make justice reign’.

Churchill was much impressed by this Brazzaville Declaration, as it became known. It was bound, he wrote to his Foreign Minister, Anthony Eden, a few days later, ‘to have a great effect on the minds of Frenchmen on account both of its scope and its logic. It shows de Gaulle in a light very different from that of an ordinary military man.’ Were the Vichy Government to bomb Gibraltar, Churchill assured de Gaulle two weeks later, or to take other aggressive action, ‘we shall bomb Vichy, and pursue the Vichy Government wherever it chooses to go’.

Not Pétain’s France, however, but Mussolini’s Italy, was on the eve of military action.

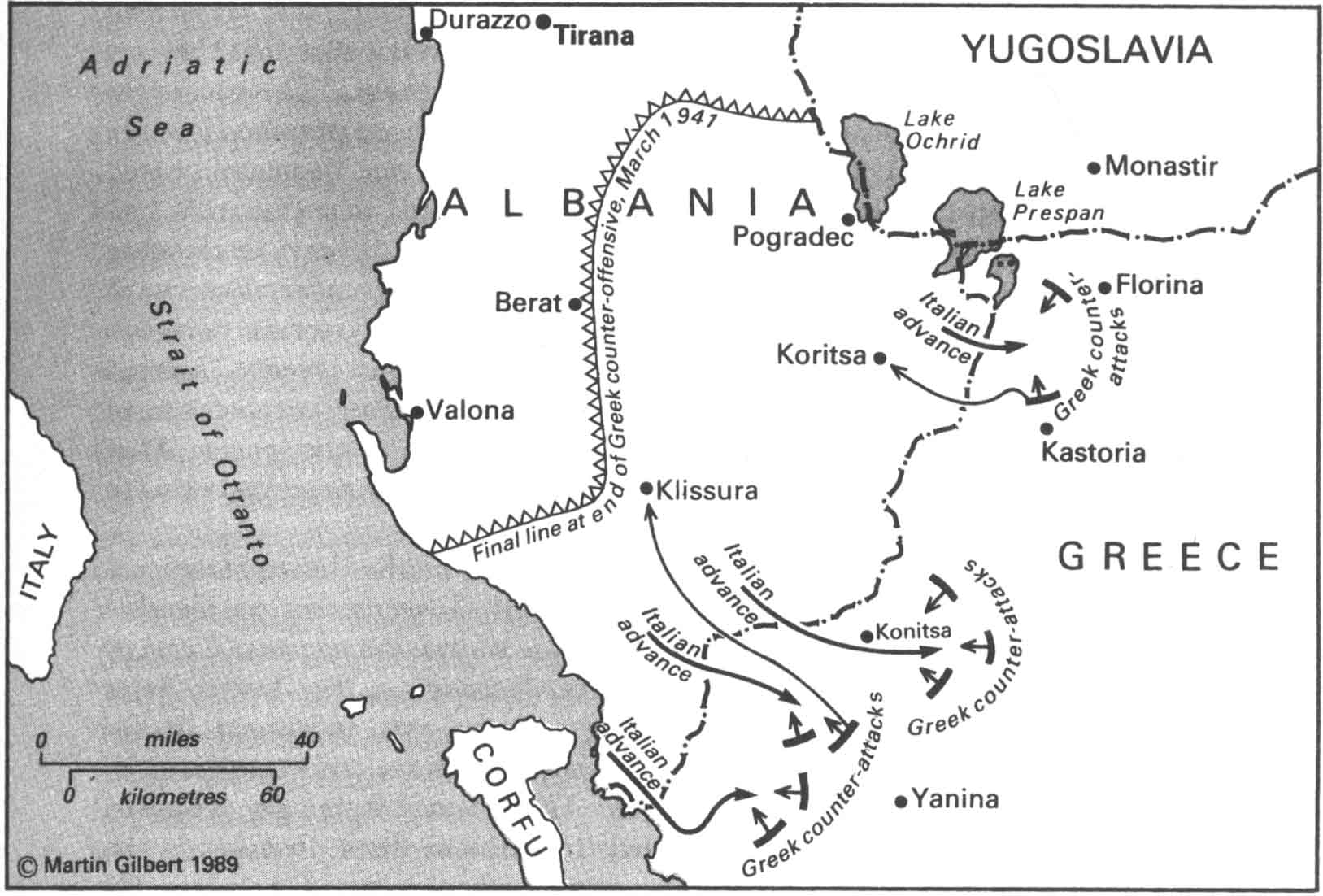

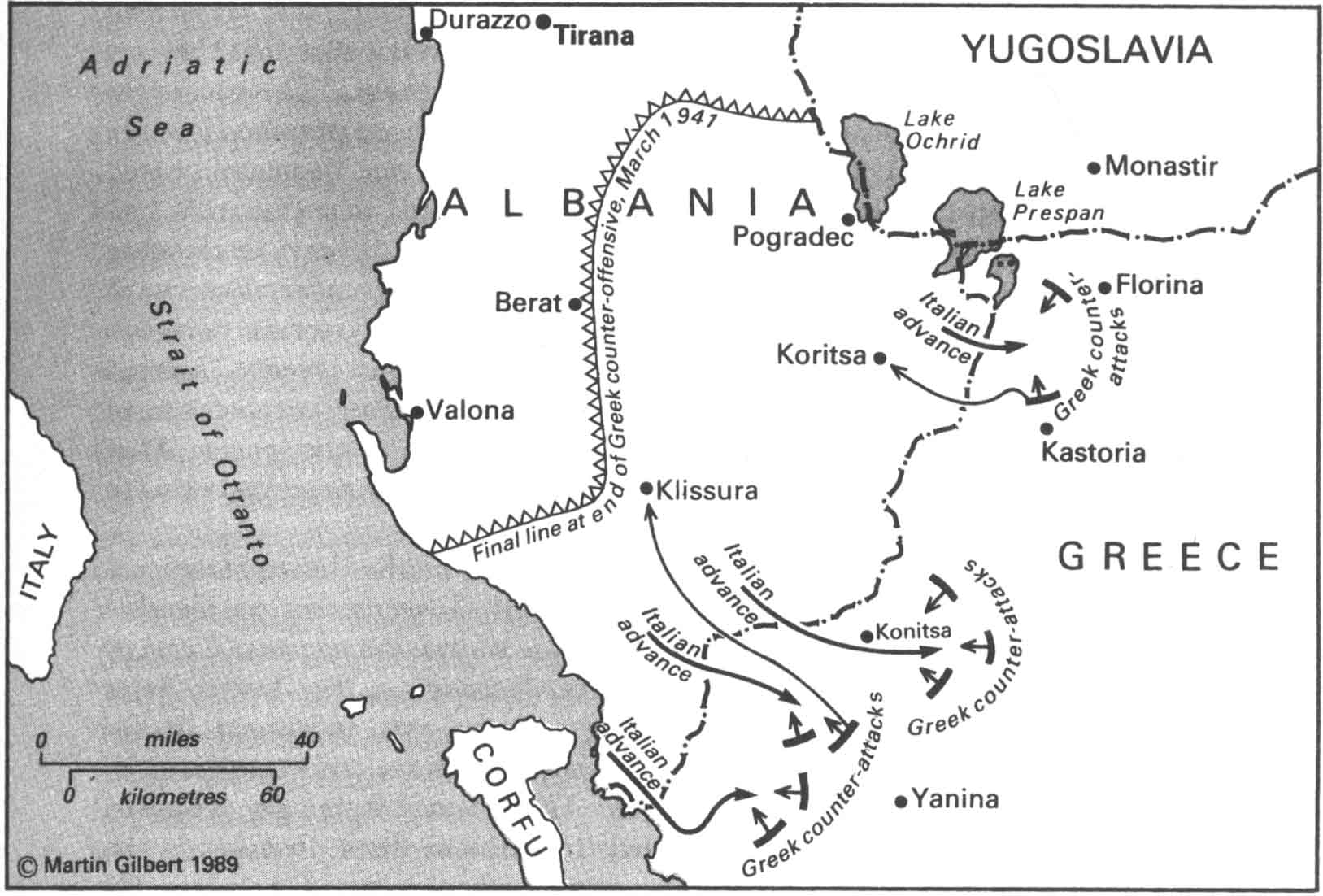

On 28 October 1940, Italian forces in Albania, their conquest of Albania a year and a half old, invaded Greece. In less than fourteen months, nine countries had been invaded without warning: Poland, Finland, Denmark, Norway, Holland, Belgium, Luxemburg, France and now Greece. Yet again, soldiers and civilians were to be subjected to air bombardment. Yet again, those in combat and those in hiding were to suffer equally the devastation and sorrow of war.

The news that Italy had invaded Greece reached Hitler in his train, Amerika, as he was on his way from Munich to Florence, where Mussolini greeted him in German with the words, ‘Führer, we are on the march!’ Hitler was furious, regarding the attack on Greece as a major strategic error. To have continued the advance into Egypt, seizing the British naval base at Alexandria, or to take Crete, in the Mediterranean, would, Hitler believed, have made far more sense. But now Italy was embroiled in a mountainous country, against a tenacious enemy, while leaving her Libyan flank exposed to a British counter-attack.

The Italian invasion of Greece, October 1940

One country apparently still determined not to be embroiled in direct military action in Europe was the United States. On October 30, two days after the Italian invasion of Greece, Roosevelt, then on a re-election campaign tour, told an audience in Boston: ‘I have said this before, but I shall say it again and again and again: Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.’

Those ‘foreign wars’ were twofold, with a distant third in prospect; in Greece, the third day of the Italian attack saw Mussolini’s forces already unable to advance as far as they had intended, and forced, as a result of bad weather conditions, to give up the plan to land on the island of Corfu. In Britain, October 1940 had seen 6,334 civilians killed, of whom 643 were children under sixteen; and in the East of Europe, so Churchill told his senior military commanders on October 31, the Germans ‘would inevitably turn their eyes to the Caspian and the prize of the Baku oilfields’.

Churchill’s forecast was not a fanciful one; on the day that he made it, the German ruler of the Warthegau, Artur Greiser, was lunching with Hitler and Martin Bormann at the Chancellery in Berlin. Greiser was upset that the eyes of the German people were now turned west instead of east. The spaces that Germany needed for expansion and settlement could only be obtained from the East. ‘The Führer agreed that this opinion was a correct one,’ Bormann noted.

British Intelligence, based partly on Enigma, confirmed what Churchill had forecast and Greiser wished. On October 31, British Military Intelligence reported that a vast programme of motorization was being undertaken in the German Army, that there had been a steady movement of German divisions from western Europe to Poland, and that there were now seventy German divisions in eastern and south-eastern Europe. The number of mechanized divisions was also increasing; these would be fully trained by the spring. What Military Intelligence did not know was whether these forces were intended for operations in Russia or in the Middle East.

Four days before Italy’s invasion of Greece, Britain and the United States had concluded a secret agreement which gave the British Government considerable confidence in its long-term ability to turn the tide of invasion against Germany during 1942. Under this agreement, signed on October 24, the United States Administration agreed ‘to equip fully and maintain’ ten additional British divisions, using American weapons then under production, and equipping the divisions in time for the ‘campaign of 1942’. The United States also promised to ‘ensure priority’ for the material needed to maintain these divisions in the field. ‘This is splendid’, was Churchill’s comment when he heard the news. He was also told, on October 26, that the current British request for military supplies to be purchased from the United States included seventy-eight million rounds of rifle ammunition, seventy-eight million cartridges suitable for the Thompson machine gun, more than two and a half million tons of explosives, and 250 aircraft engines. In urging Roosevelt to approve these orders, and to expedite them, Churchill telegraphed on October 27: ‘The World Cause is in your hands.’

Britain’s plans to take the land war to Germany in 1942 were a sign of her leaders’, and of her people’s determination not to accept the German mastery of Europe. But the fury of the German air attacks was unabated. On October 28, more than 450 German aircraft attacked strategic targets throughout southern England. Twenty-eight were shot down, for the loss of only seven British fighters, but the damage which they did was considerable. In London, fifty people were killed while sheltering under a railway arch at Croydon, and eighteen in a church crypt at Southwark. On November 1, determined to carry the war to both enemy capitals, British bombers struck at military targets in Berlin and Rome. But Churchill was not yet content, writing to the Chief of the Air Staff: ‘The discharge of bombs on Germany is pitifully small.’

Britain now sent what aid she could to Greece, including a squadron of fifteen aircraft which had been stationed in Egypt to defend Alexandria and the Suez Canal against an attack by the Italians, whose troops were now entrenched sixty miles inside the Egyptian frontiers, at Sidi Barrani. ‘If Greece was overwhelmed,’ Churchill warned his War Cabinet on 4 November, ‘it would be said that in spite of our guarantees we had allowed one more small ally to be swallowed up.’

Britain’s guarantee to Greece had been given in April 1939. There was almost no military equipment, however, that could be spared. Some British troops, some anti-aircraft guns and a coastal defence battery were on their way. But it was to be by Greece’s own exertions that the Italian invasion was brought to a halt. On November 4, a week after the Italian attack had begun, Greek forces, counter-attacking, began to drive the Italians back towards their starting points.

***

On November 3, for the first night since September 7, there was no German air raid over London. The German Air Force was reaching a point of exhaustion. In the previous three months, 2,433 German aircraft had been shot down over Britain, and more than six thousand German airmen killed. These losses were particularly unacceptable in view of Hitler’s determination to move against Russia.

‘Everything’, Hitler told General Halder on November 4, ‘must be done so that we are ready for the final showdown’. There were those in the German High Command who wanted to use the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus—the Straits—as a means of opening the way, through Turkey, to Syria, which was under Vichy control. ‘We can only go to the Straits’, Hitler told Halder, ‘when Russia is defeated.’