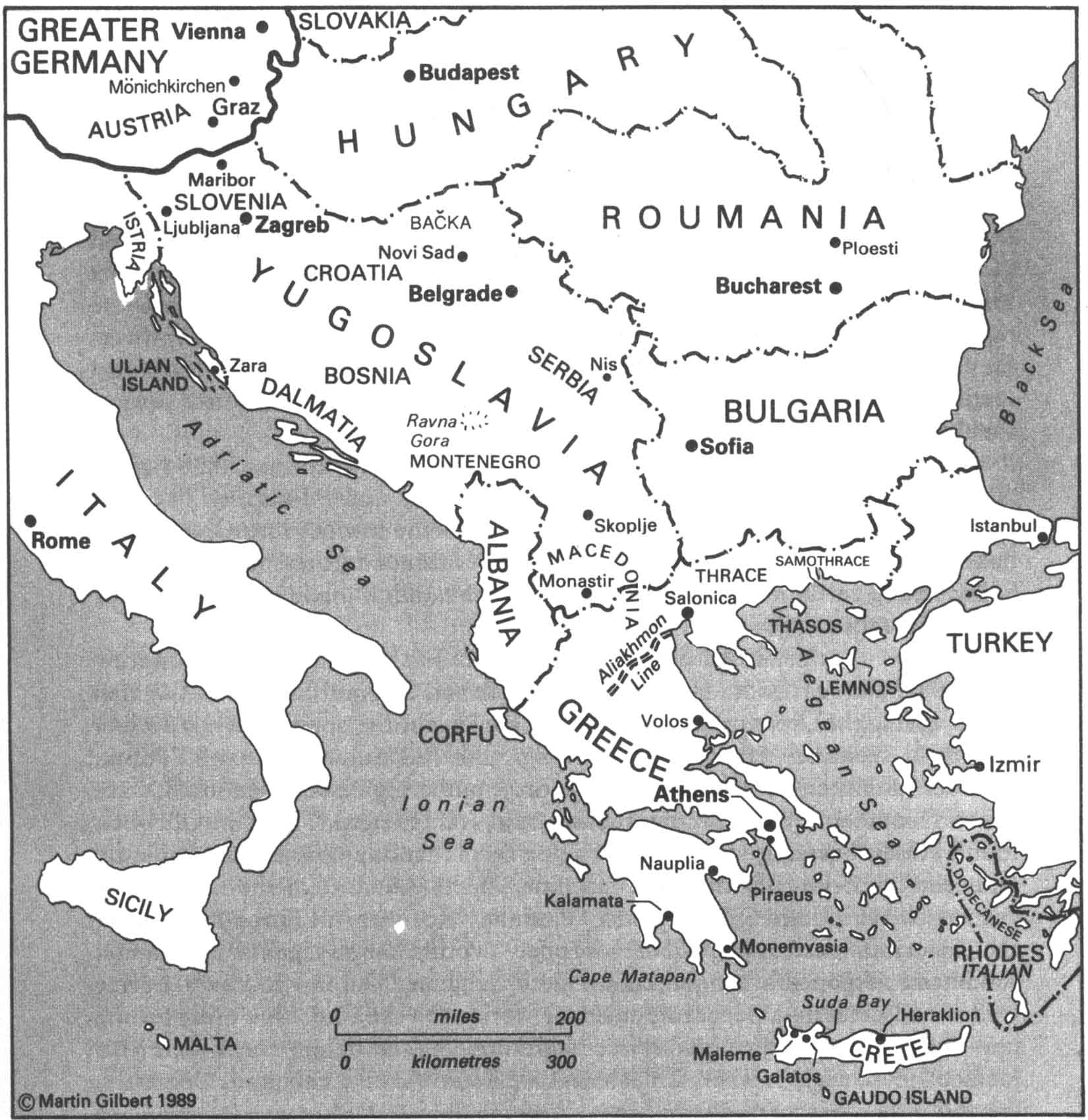

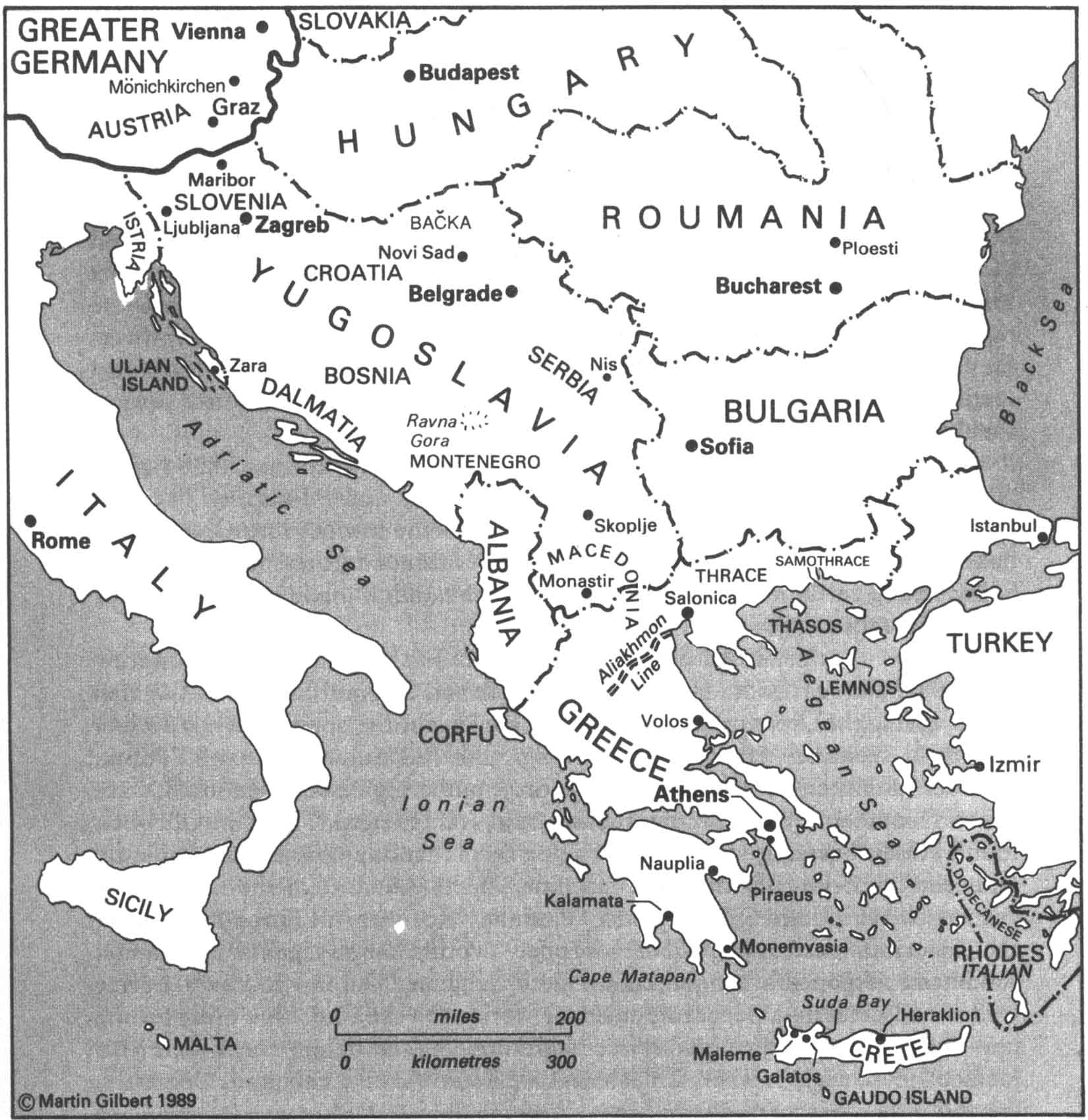

Yugoslavia and Greece, April 1941

As German forces completed their forward movements in Bulgaria, on the eastern border of Greece, and King Boris of Bulgaria finally committed himself to the Axis, the situation for Greece had become one of imminent danger. On 18 March 1941 it was judged by British Intelligence that Paul, the Prince Regent of Yugoslavia, had, like King Boris, committed himself to the Germans, thereby also exposing the northern border of Greece to a German onslaught. British diplomats in Yugoslavia were authorized to do their utmost to secure the overthrow of the pro-German Government, even if this meant giving support to subversive measures.

On March 20, Prince Paul asked his Cabinet if they would agree to Hitler’s demand, that Yugoslavia join the Axis, and allow the free passage of German troops through Yugoslavia to Greece. Four Ministers resigned rather than accept these terms. On March 25, however, in Vienna, the Yugoslav Prime Minister, Cvetković, signed Yugoslavia’s adherence to the Tripartite Pact. Watched not only by Hitler, but by the Japanese Ambassador in Berlin, General Oshima, Yugoslavia became a member of the ever widening Axis.

The news of Yugoslavia’s commitment to Germany coincided with two further blows to the Allied cause. On March 25 six Italian motor torpedo boats, commanded by Lieutenant Luigi Faggioni, entered Suda Bay in Crete, where a British naval convoy had brought troop reinforcements and arms. There, they so severely damaged the British cruiser York that she had to be beached. At the same time, Rommel, who in a surprise forward move had retaken the Western Desert fort of El Agheila from British troops, decided, contrary to his instructions and against Italian protests, to develop a full-scale offensive. The British forces facing him were depleted in men, munitions and aircraft because of the priority being given to helping Greece. ‘I have to hold the troops back to prevent them bolting forward,’ Rommel wrote to his wife on March 26. ‘They’ve taken another new position, twenty miles farther east. There’ll be some worried faces among our Italian friends.’

Those ‘Italian friends’ had other causes for alarm as well. On March 27, after twelve days of bitter fighting, their forces in Eritrea were driven from Keren. At the same time, their principal naval forces were steaming off Cape Matapan, the southernmost point of Greece, unaware that a formidable British force, alerted by the regular British reading of Italy’s most secret coded radio signals, was steaming towards them. In the ensuing battle, fought first off Matapan and then off the island of Gaudo, south of Crete, the Italians lost five out of eight cruisers and three out of thirteen destroyers. About 2,400 Italian sailors were drowned. The cost to Britain was two naval aircraft. Among those in the battle was a Royal Navy Midshipman, Prince Philip, the son of Prince Andrew of Greece; for his work in directing the searchlights of the Valiant on two of the Italian cruisers, he was mentioned in despatches.

The Battle of Matapan eliminated the Italian Navy as a force in the struggle which had just begun in the Adriatic, Ionian and Aegean Seas. Throughout 26 March there had been mass demonstrations in many of the cities and towns of Yugoslavia, against the signing of the Tripartite Pact—the trade unions, the peasants, the Church, and the Army making common cause. In the early hours of the following morning, March 27, the Cvetković Government was overthrown, and the Prince Regent replaced by the heir to the throne, the seventeen-year-old King Peter. The new Government, headed by the Yugoslav Air Force commander, General Dusan Simović, at once withdrew from the Tripartite Pact. Within forty-eight hours of having secured his northern route to Greece, Hitler had lost it. Angrily, he told his military commanders that he was determined ‘to smash Yugoslavia militarily and as a State’. The attack must begin as soon as possible. ‘Politically’, Hitler explained, ‘it is especially important that the blow against Yugoslavia be carried out with merciless harshness and that the military destruction be done in Blitzkreig style.’

Once more, ‘lightning war’ was to destroy one enemy, and frighten another. Turkey would also be persuaded by such an example to maintain her neutrality. Later that morning, in a fifteen-minute interview, Hitler offered the Hungarian Minister the Bačka province of Yugoslavia in return for Hungarian help. ‘You can believe me’, he said, ‘that I am not pretending, for I am not saying more than I can be answerable for.’ To the Bulgarian Minister in a five-minute interview, he offered the Yugoslav province of Macedonia, as well as Greek Macedonia, which was to have been Yugoslavia’s reward for joining the Axis. ‘The storm’, Hitler told the Bulgarian Minister, ‘will burst over Yugoslavia with a rapidity that will dumbfound those gentlemen!’

During March 27, six hundred German aircraft were flown to airfields in Roumania and Bulgaria from German airfields along the whole of the Channel Coast, as well as from Sicily and from Libya. With their arrival, the total German air strength ready to strike at either Yugoslavia or Greece had reached a thousand. Belgrade, the Yugoslav capital, was particularly vulnerable. That evening, Hitler signed his war Directive No. 25. Yugoslavia and Greece would be attacked simultaneously. The invasion of Russia must be postponed from May to June.

Yugoslavia now faced the full weight of Hitler’s fury. Even if she were to make ‘initial professions of loyalty’, Hitler wrote in his directive, she ‘must be regarded as an enemy and beaten down as quickly as possible’. Meanwhile, internal tensions were to be encouraged by giving political assurances to the Croats. As to the start of the attack, as soon as sufficient aircraft were in place, and the weather allowed, ‘the ground installations of the Yugoslav Air Force and the city of Belgrade will be destroyed from the air by continual night and day attack’.

The meaning of such an attack could not be in doubt; on March 28 it was announced that 28,859 British civilians had been killed in the previous seven months of air bombardment, and a further 40,166 seriously injured. In March 1941 alone, 4,259 civilians had been killed, among them 598 children under sixteen. At sea, the German submarine sinkings had also continued. ‘The strain at sea on our naval resources’, Churchill telegraphed to Harry Hopkins on March 28, ‘is too great for us to provide adequate hunting groups, and this leads to a continuance of heavy disastrous losses inflicted on our immense traffic and convoys. We simply have not got enough escorts to go round, and fight at the same time.’

The German submarine sinkings of merchant ships was a daily worry for the British people and their leaders; but for the long-term outcome of the war, the last week of March saw two secret developments of profound significance for the Western Allies. On March 27 the American—British Staff Conversations in Washington reached agreement on Joint Basic War Plan Number One between Britain and the United States, a plan which envisaged ‘war against the Axis Powers’. Comprehensive in its scope, the War Plan set out in detail what the dispositions of the land, sea and air forces of Britain and the United States would be, from the moment that America might enter the war. Also known as Defence Plan No. 1, it envisaged first the defeat of Germany in Europe, to be followed, should Japan become a belligerent, by the defeat of Japan in Asia.

Of equal relevance, as it was to prove, to the eventual defeat of Japan, was another secret development that week. On March 28, a group of Western scientists discovered a new element, the properties of which showed it to be an essential component of nuclear fission, and the evolution of an atomic bomb. In 1789 a newly discovered element had been named uranium, after the planet Uranus. The new element of 1941 was to be named after the planet Pluto, which had itself been discovered only eleven years earlier—it was to be called plutonium.

***

On March 30, in Berlin, Hitler spoke to two hundred of his senior commanders and their staff. The invasion of Russia, he said, would take place on June 22. ‘We have the chance to smash Russia while our own back is free. That chance will not return so soon. I would be betraying the future of the German people if I did not seize it now!’ Hitler then gave his commanders an explanation of his Commissar Decree. In the East, cruelty would be ‘kindness for the future’. All Russian commissars, identified by the red stars enclosed in a golden hammer and sickle on their sleeves, were criminals, and must be liquidated. ‘It is not our job to see that these criminals survive.’

Sensing the shock of many of the officers present, Hitler told them: ‘I know that the necessity of making war in such a manner is beyond the comprehension of you generals, but I cannot and will not change my orders, and I insist that they be carried out with unquestioning and unconditional obedience.’

There had been no need to browbeat subordinates in carrying out orders in the concentration camps; at the end of March it was learned in the West, through the Polish Government-in-exile, that more than three thousand Poles had been murdered in Auschwitz, or had died there from exposure and cold, in the previous ten months.

***

On March 30, in the Western Desert, Rommel now advanced across Cyrenaica, from which the British had so recently driven the Italians. Further east, in Iraq, an anti-British general, Rashid Ali, seized power on April 2, cutting off the oil pipeline to the Mediterranean. Hitler, elated at this blow to Britain’s position in the Middle East, ordered Vichy arms from Syria to be sent to Baghdad, and German military experts to be flown out to help Rashid Ali maintain his power.

Only in the war in East Africa, where Britain was total master of the Italian secret radio communications, did the British forces continue to make unbroken progress; on April 3, the day after Rashid Ali’s seizure of power in Baghdad, five Italian destroyers on their way from Massawa to Port Sudan were attacked by a squadron of torpedo-carrying aircraft. Four were sunk.

***

Since March 26, in Russia, under Order No. 008130, the Western Special Military District had been under instructions to institute a ‘state of readiness’, to be maintained until June 15. Urgent instructions were also sent to the Baltic, Western and Kiev Military District commanders to strengthen their frontier fortifications. In a massive effort to make up for past neglect, 58,000 men began work on fortifications in the Baltic district, 35,000 in the Western district and 43,000 in the Kiev district. The work was impeded, however, by a shortage of concrete, timber and cable; and, in what was meant to be a continuous defence line, there were several gaps of between five and fifty miles. One gap, particularly serious, was in the Grodno ‘fortified district’. Plans were being drawn up to make the gap less dangerous by building two ‘support points’, but these had not been completed by the third week of June.

Also at the end of March, at the persistent urgings of Timoshenko and Zhukov, Stalin agreed to call up 500,000 men to the border military districts, to augment the infantry divisions there; a few days later he agreed to the despatch of a further 300,000 men to the fortified districts, among them specialists in artillery, engineering, signals, air defences and Air Force logistics. Their training, and the implementation of a defensive strategy, was planned to begin in March and be completed by October. Yet time was clearly running out: in the first week of April, from Tokyo, Richard Sorge sent a radio message to Moscow in which he stated, citing his most senior German contact in Tokyo: ‘According to the German Ambassador, the German General Staff has completed all its preparations for war. In Himmler’s circles and those of the General Staff there is a powerful trend to initiate war against the Soviet Union.’ This time, Sorge gave no date.

Himmler was in fact training his SS troops for combat with an intensity not seen before even in SS military circles. Between January and April, ten SS men had been accidentally killed in combat training, and sixteen wounded. They were expecting to be used next in the planned occupation of Vichy France, Operation Attila, but this Hitler had postponed. On April 3 Himmler summoned the SS military commanders to Berlin, and told them to prepare for action in Greece. At the same time, uninterrupted by the Balkan imbroglio, the Special Task Forces continued preparation for their work in Russia. On the day after Himmler’s talk to the SS commanders who would be fighting alongside the German Army in Greece, that same Army agreed to give the Special Task Forces virtually unrestricted activity behind the lines, and they were specifically authorized ‘to take executive measures affecting the civilian population’. These ‘executive measures’ were to be mass murder.

***

On April 3, Rommel’s combined German and Italian Army forced the British to evacuate Benghazi. ‘We’ve already reached our first objective’, Rommel wrote to his wife, ‘which we weren’t supposed to get to until the end of May. The British are falling over each other to get away.’ That day, in Hungary, the Prime Minister, Count Pal Teleki, committed suicide, feeling that the decision of the Hungarian Regent, Admiral Horthy, to join with Germany in the invasion of Greece, forfeited Hungary’s honour. In his War Directive No. 26, Hitler, also on April 3, confirmed that Hungary was ready to take part, not only in occupying the Yugoslav province of the Bačka, but also in ‘further operations for the destruction of the enemy’. Bulgaria would ‘get back’ Macedonia. Roumania would limit her efforts ‘to guarding the frontiers with Yugoslavia and Russia’. The Italians would also move against Yugoslavia, but this would only be once the German attack ‘begins to be effective’.

On April 4, as the German forces made their final preparations for their Balkan offensive, Rommel’s troops entered Benghazi, from which the British had already withdrawn. That same day, in mid-Atlantic, a German commerce raider the Thor, disguised as a merchant ship, sank the British armed merchant cruiser Voltaire. In the first six months of 1941, these German decoy ships were to sink thirty-eight merchantmen, while the warship raiders, such as the Pinguin, sank a further thirty-seven.

At Sachsenhausen concentration camp, German doctors were continuing their experiments in euthanasia and death by gassing, using concentration camp prisoners for their experiments. ‘Our work here’, one doctor, Fritz Mennecke, wrote to his wife, ‘is very, very interesting.’ He was collecting material for ‘large quantities of new experiments’.

***

On April 5, in North Africa, despite Italian hesitations, Rommel ordered his Army to continue its eastward march. ‘Off at four this morning,’ he wrote to his wife that day, and he added: ‘Things are happening in Africa. Let’s hope the great stroke we’ve now launched is successful.’ In Italian East Africa, the final humiliation came that day, when the Italian Viceroy of Ethiopia, the Duke of Aosta, ordered the evacuation of the capital, Addis Ababa. In Moscow, Stalin spent much of the evening of April 5 with the Yugoslav Minister in Moscow, Gavrilović, promising that, if Yugoslavia were attacked, the Soviet Union would adopt an attitude of goodwill, ‘based on friendly relations’. ‘And if the Germans, displeased, turn against you?’ Gavrilović asked. ‘Let them come!’ was Stalin’s confident reply.

Even as Stalin spoke, the German Air Force launched Operation Castigo, the bombing of Belgrade. The first bombs fell at five o’clock on the morning of April 6. The battle for Yugoslavia had begun.

Swiftly, and with savage brutality, Yugoslavia was struck, and overrun. In the bombing of Belgrade, the principal purpose of which was to create confusion through terror, 17,000 civilians were killed: the largest number of civilian deaths by bombing in a single day in twenty months of war. As had happened in Warsaw in September 1939, and in Rotterdam in May 1940, so in Belgrade in April 1941, a virtually defenceless civilian population, unprepared for the onslaught, and in this instance swelled by many Yugoslavs from other towns and villages who had come to their capital to celebrate Palm Sunday, was subjected to a day of aerial slaughter. Simultaneously, all Yugoslavia’s airfields were bombed, and most of its six hundred aircraft destroyed on the ground.

Several German armies were on the move on April 6; one, advancing from Austria and Hungary, drove on Belgrade; another, advancing from Bulgaria, drove on Niš, Skoplje and Monastir; another, also advancing from Bulgaria, drove into Greece, striking at the port city of Salonica. That same day, the German Air Force bombed the Greek port of Piraeus. Six Allied ships with military cargoes were sunk before the port itself was devastated when a British merchant ship, the Clan Fraser, hit by German bombs, blew up with two hundred tons of explosives on board. In the massive explosion, ten other ships were sunk.

The Italians, eager to revenge the humiliation of their failed invasion of Greece, prepared yet again to advance from Albania; they also awaited the orders to march from Istria, in the north, and from the Italian enclave at Zara, against the Dalmatian coast of Yugoslavia. The Hungarians, too, were poised to strike. Twenty-eight Yugoslav divisions faced more than fifty Axis divisions; the Axis divisions had far greater armoured forces, and overwhelming air superiority. That night, hoping to delay German railway movement from Bulgaria to the front, six British bombers, flying from bases in Greece, bombed the railway yards in Sofia, the Bulgarian capital. But any gains from the raid were seriously offset by the sinking that day in the eastern Mediterranean of the Northern Prince, a British merchant ship bringing the Greek Army badly needed raw materials for the manufacture of explosives.

As Yugoslavia faced defeat and disintegration, with Italy among those who would share the territorial spoils, the Italian armies in Eritrea were finally and totally defeated, with the surrender of Massawa. Of the thirteen thousand defenders, more than three thousand had been killed. In North Africa, however, the German and Italian forces under Rommel’s command were completing the reconquest of Cyrenaica. ‘After a long desert march,’ Rommel wrote to his wife on April 10, ‘I reached the sea the evening before last. It’s wonderful to have pulled this off against the British.’ Less than a year had passed since Rommel had last reached the sea in triumph—at Les Petites Dalles on the Channel coast.

Stalin, watching as German forces entered the southern Yugoslav city of Niš and advanced towards Belgrade, approved a Soviet General Staff directive on April 8 to the Western and Kiev Special Military Districts, ordering the maintenance and completion of the frontier Fortified Areas. The necessary improvements were to begin by May 1.

Yugoslavia and Greece, April 1941

That night, April 8, German bombers struck again at the British aircraft factories around Coventry. Considerable damage was done to three factories. That same night, in Greece, German forces occupied Salonica, and on the following day the Greek commander of the region, General Bakopoulos, was ordered by the Greek Supreme Commander to surrender his 70,000 soldiers. At Hitler’s Chancellery in Berlin, the German diplomat Walther Hewel noted a ‘magnificent mood’.

April 9 marked the first anniversary of the German invasion of Norway. In Oslo, there were silent demonstrations in streets, schools and workplaces. Over Berlin, as a reprisal for the bombing of Belgrade, British bombers dropped explosive and incendiary bombs on the city centre, destroying several public buildings. Hitler had to spend part of the night in his air raid shelter.

In Britain, the shock of the simultaneous German invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece was met with defiance. On April 9, Churchill told the House of Commons that once the Battle of the Atlantic had been won, and Britain had received ‘the constant flow of American supplies which is being prepared for us’, then however far Hitler might go, ‘or whatever new millions, or scores of millions, he may lap in misery, he may be sure that, armed with the sword of retributive justice, we shall be on his track’.

It was on April 9, in the northern sector of the Greek frontier, that a British Army patrol crossed the frontier with Yugoslavia, near Monastir. There, it found groups of Yugoslav soldiers drifting across the frontier into Greece. The patrol returned to report that all Yugoslav resistance in the south was over. Snow falling in the mountains, and rain in the valleys, made any effective air reconnaissance impossible.

On April 10, the British Expeditionary Force in Greece began to withdraw from the Salonica front. In northern Yugoslavia, Zagreb fell to the German Army, giving the Croat nationalist leader Ante Pavelić the opportunity to declare Croatia a separate State. In North Africa, the Australian forces in Tobruk, together with their British artillery support, numbering 24,000 men in all, were cut off from their retreating comrades in arms, and besieged. That day, Goebbels found Hitler ‘beaming with joy’. But two events that day were an omen, hardly glimpsed in Berlin, of things yet to come. In the Atlantic, in the first hostile gesture by the United States against Germany since war in Europe had begun, the American destroyer Niblack dropped depth charges against a German submarine responsible for sinking a Dutch freighter. And in Moscow a decree was issued creating a separate logistical service for the Red Air Force, setting up airbase areas and ground service battalions. Special fighter corps were also formed, to strengthen the air defences of Moscow and Leningrad. Belatedly, slowly, with a desperate lack of resources, the Soviet Union was awakening to the danger.

Hitler, with victory over Yugoslavia now certain, travelled from Berlin to the tiny village of Mönichkirchen in southern Austria, to be as near as possible to his troops while still remaining on German soil. For two weeks, living in his train Amerika, he followed the course of the Balkan campaign. Among those who visited him on the train was Franz von Werra, who had finally returned to Germany after his escape that January while he had been a prisoner-of-war in Canada.

With Yugoslavia in travail, both Italy and Hungary advanced on April 11 for their part of the spoil, the Italians entering the Slovene capital of Ljubljana and the Hungarians advancing on the principal Bačka town of Novi Sad. The Italians also chose April 11 to advance across the Albanian border into Greece, occupying the same regions from which they had earlier been driven with such ignominy. On the following day, as other Italian units began their advance along the Dalmatian coast, occupying the island of Uljan, German motorized units reached the outskirts of Belgrade.

Once more, a moment of German triumph was paralleled elsewhere by a little noticed move of great significance for the future of the war—the occupation of the Danish colony of Greenland by United States forces. This was one more step towards the American policy of support for Britain in the Atlantic, by means of shared bases and extended zones of naval patrol. That same day, Roosevelt told Churchill that the United States would extend her security zone and patrol areas in the Atlantic as far east as the 25th meridian.

Even so, Britain’s position at sea was grave; in the three days up to April 10, 31,000 tons of Allied merchant shipping had been sunk at sea. German bombing had also reached a renewed intensity; on April 12 Churchill was in Bristol where, together with the new American Ambassador, Gilbert Winant, he visited the city centre, shattered by a raid the night before. Yet British morale was not being broken. ‘People were still being dug out,’ General Ismay later recalled, in a letter to Churchill, ‘but there was no sign of faltering anywhere. Only efficiency and resolution. At one of the rest centres at which you called, there was a poor woman who had lost all her belongings sobbing her heart out. But as you entered, she took her handkerchief from her eyes and waved it madly shouting “Hooray, hooray”.’

That April 12, in Greece, Australian troops had been among those surrendering to the superior firepower of the Germans, as they advanced on the Aliakhmon Line. In Yugoslavia, April 13 saw the occupation of Belgrade, the eighth European capital to be conquered by German arms in a year and a half. According to one account, the first Yugoslav civilian to be shot in cold blood in the capital that day was a Jewish tailor who, as the German troops marched by, spat at them and shouted: ‘You will all perish.’

In Moscow, on the day of the fall of Belgrade, in an attempt to ensure that he was not stabbed in the back, Stalin signed a Soviet—Japanese Neutrality Pact, valid for five years. It was an agreement which gave both sides advantages. Stalin was now free to concentrate on meeting a German threat from the West. Japan could focus her attention on South East Asia and the Pacific. At the Kazan railway station in Moscow, Stalin made a rare public appearance to say goodbye to the Japanese Foreign Minister, Yosuke Matsuoka, remarking: ‘We are both Asiatics.’ But he also sought out the German Ambassador on the station platform, telling him: ‘We must remain friends and you must now do everything to that end.’ Then, turning to an officer whom he had never seen before, the acting German Military Attaché, Colonel Krebs, and after checking to make sure that Krebs was in fact a German, Stalin called out for all to hear: ‘We shall remain friends with you—in any event!’

On April 14, the day after this scene in Moscow, Stalin approved a directive, issued by the Soviet General Staff, for the artillery emplacements in the Fortified Areas to be ‘immediately mounted in combat emplacements’; and for the Military Districts in which they were situated to be put ‘in combat readiness’. Even where the full equipment needed by the gun emplacements was not available, it was still ‘absolutely necessary’ to mount the armoured doors, and to provide ‘proper care and maintenance’ of whatever armaments had been installed. In all, 2,300 major artillery emplacements were to come under the new directive; but such were the shortages of materials that less than a thousand were in fact completed or equipped by the third week of June.

In the Hungarian-occupied areas of northern Yugoslavia, April 14 marked the first day of an extension of the terror against civilians in the new area of conquest; for on that day Hungarian armed detachments seized five hundred Jews and Serbs, and shot or bayoneted them to death.

As the German armies now broke through more and more strongpoints along the Aliakhmon Line, and some Greek soldiers, demoralized by the imminent disaster, fired on their own officers, Hitler was continuing uninterrupted with his Eastern plans. On April 15 a German aircraft, forced down near Rovno, almost a hundred miles inside the Soviet frontier, was found by the Soviets to be carrying a camera, exposed film and a detailed topographical map of the Soviet frontier region.

All Europe was now caught up in one aspect or another of war. On April 16, as the Greek Commander-in-Chief, Marshal Papagos, contemplated surrender, and pressed the British to withdraw their forces from Greece altogether ‘in order to save Greece from devastation’, London experienced one of the most severe and indiscriminate bombing attacks of the war, a retaliation for Britain’s deliberate raid on the centre of Berlin a week earlier. In all, 2,300 people were killed. Among them were more than forty Canadian soldiers, sailors and airmen on leave in the capital. In an air battle over southern England, as fighters sought to shoot down the German raiders, two Polish pilots lost their lives, Pilot Officer Mieczyslaw Waskiewicz and Pilot Officer Boguslaw Mierzwa.

***

On April 17 the Yugoslav Government signed the act of surrender in Belgrade. A total of 6,000 Yugoslav officers and 335,000 men had been taken prisoner. Once more, overwhelming military superiority, in numbers, firepower and air support, had proved too much even for the most determined defenders. On the following day, in Greece, the Germans broke through the last defences on the Aliakhmon Line, held by Allied troops from New Zealand. In despair, not only at the German military advance, but at the growing signs of defeatism and even treachery in Greek Government circles, the Greek Prime Minister, Alexander Koryzis, after having been refused permission by the Greek King to resign, kissed the King’s hand and returned to his home, where he shot himself.

That day, two men whose armies had not yet been in combat, chose different ways to reflect on the rapid Greek collapse. In Moscow, Stalin approved a further directive of the Soviet General Staff, substantially increasing the number of troops assigned to defend the Soviet frontier. At Mönichkirchen, Hitler, on his train, discussed with his architect Albert Speer the building deadlines for the completion of the proposed new Government buildings in the centre of Berlin.

It was also on April 18 that a British brigade landed at Basra, on the Persian Gulf, to challenge the pro-German Government which General Rashid Ali had set up in Baghdad. Two weeks later, 9,000 Iraqi troops attacked the British force of 2,250. The British successfully resisted the attack.

In Greece, on April 19, British troops moved back to the ports of southern Greece, chief among them Nauplia, Kalamata and Monemvasia, to prepare to embark for Crete, their evacuation made possible by the determined defence of Thermopylae by British, Australian and New Zealand units. In North Africa, a strong British commando force which landed at Bardia that day in an attempt to relieve the soldiers besieged in Tobruk was driven off. Learning from the Germans’ Enigma messages that Rommel was to be reinforced by a German armoured division, on April 21 Churchill and his Chiefs of Staff agreed to send tank reinforcements from Britain to Egypt. This was Operation Tiger, a bold move, and a risky one, as the threat of a German invasion of England had not entirely receded.

***

On April 20, Hitler’s fifty-second birthday, a German soldier, Corporal Rohland, was shot and fatally wounded at a Métro station in Paris. As a reprisal, the German Governor of the Greater Paris district, Otto von Stuelpnagel, an Army officer who had been a supporter of Hitler since before 1933, ordered the execution of twenty-two civilian hostages. Their deaths were announced in special red posters displayed throughout the capital.

***

On April 23 the Greek Army surrendered to the German and Italian invaders. Several thousand Greek soldiers had been killed, and more than nine hundred British, Australian and New Zealand troops. That day, in a scene repeated all over Greece, a Greek artillery major was ordered to surrender his battery. This particular major, however, had a heightened sense of the tragedy which had overtaken his country. As the official Greek Army report explained: ‘Artillery Major Versis, when ordered by the Germans to surrender his battery, assembled the guns, and after saluting them, shot himself, while his gunners were singing the National Anthem.’

The evacuation of British, Australian, New Zealand and Polish troops from Greece, Operation Demon, began on April 24 and continued for six days. In all, 50,732 men were evacuated, from eight small ports. Most of them were taken under strong naval escort to Crete. There was no time, however, to bring away their heavy weapons, trucks or aircraft. As the evacuation began, German parachute troops occupied the islands of Lemnos, Thasos and Samothrace, while Bulgaria, eager to annex the coastline of Thrace, invaded broken Greece from the north.

Despite the capitulation of both Yugoslavia and Greece, Hitler was still on board his train at Mönichkirchen. Visited there on April 24 by the Hungarian Regent, Admiral Horthy, he listened to Horthy’s warning that the invasion of Britain was fraught with a thousand dangers. ‘But if Russia’s inexhaustible riches are once in German hands, you can hold out for all eternity.’ Unknown to Horthy, April 24 saw the first day of the move of a German Air Force unit from the English Channel to Poland. This move was known to the British as a result of their reading of the German Air Force Enigma.

The evacuation of Attica, April 1941

On April 25 the British, Australian and New Zealand troops who had been defending Thermopylae in order to make the evacuation possible, were themselves forced back to the ports of Megara, west of Athens, and Rafina and Porto Rafti, east of the capital, where they too embarked. That day, with Greece at his feet, Hitler issued Directive No. 28, Operation Mercury, the invasion of Crete.