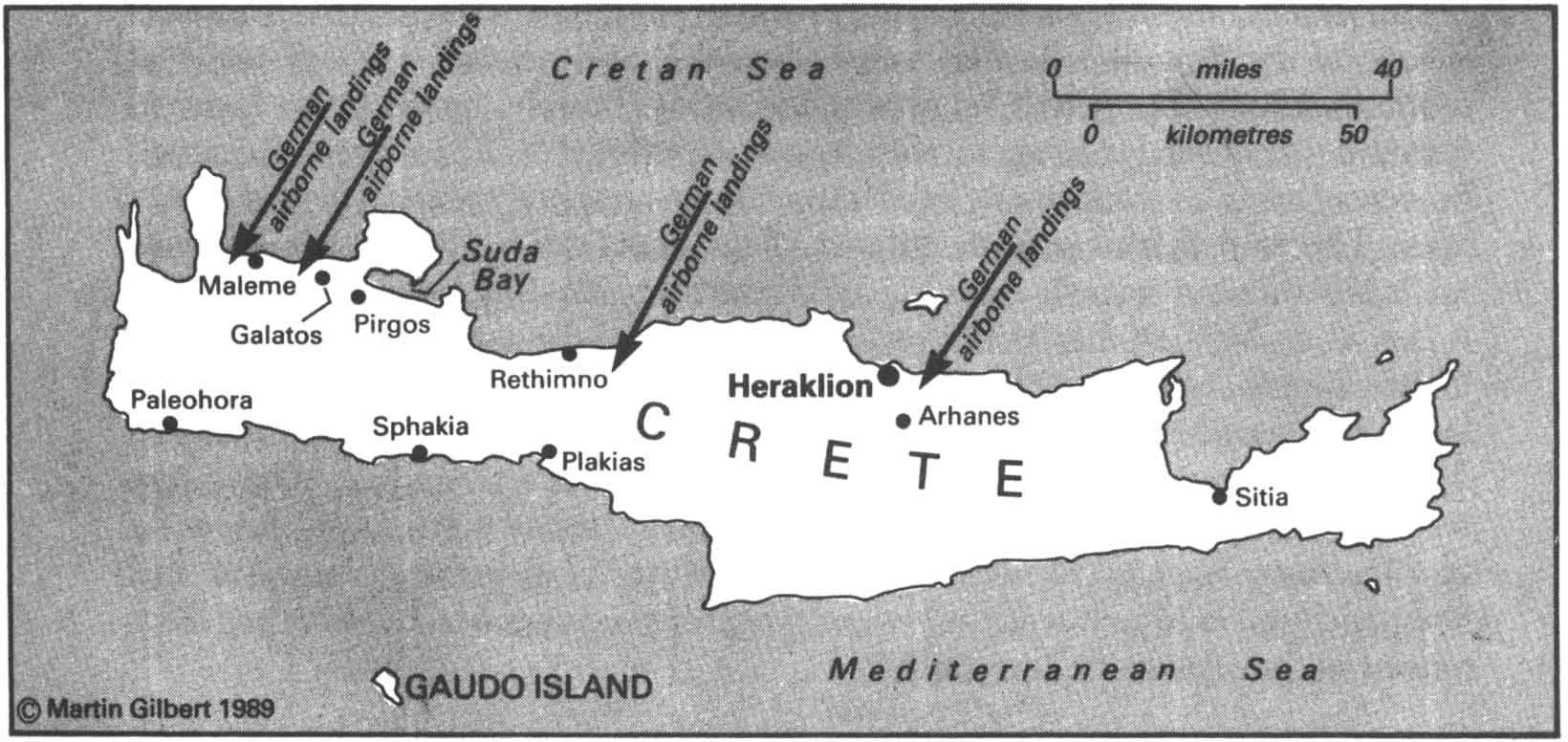

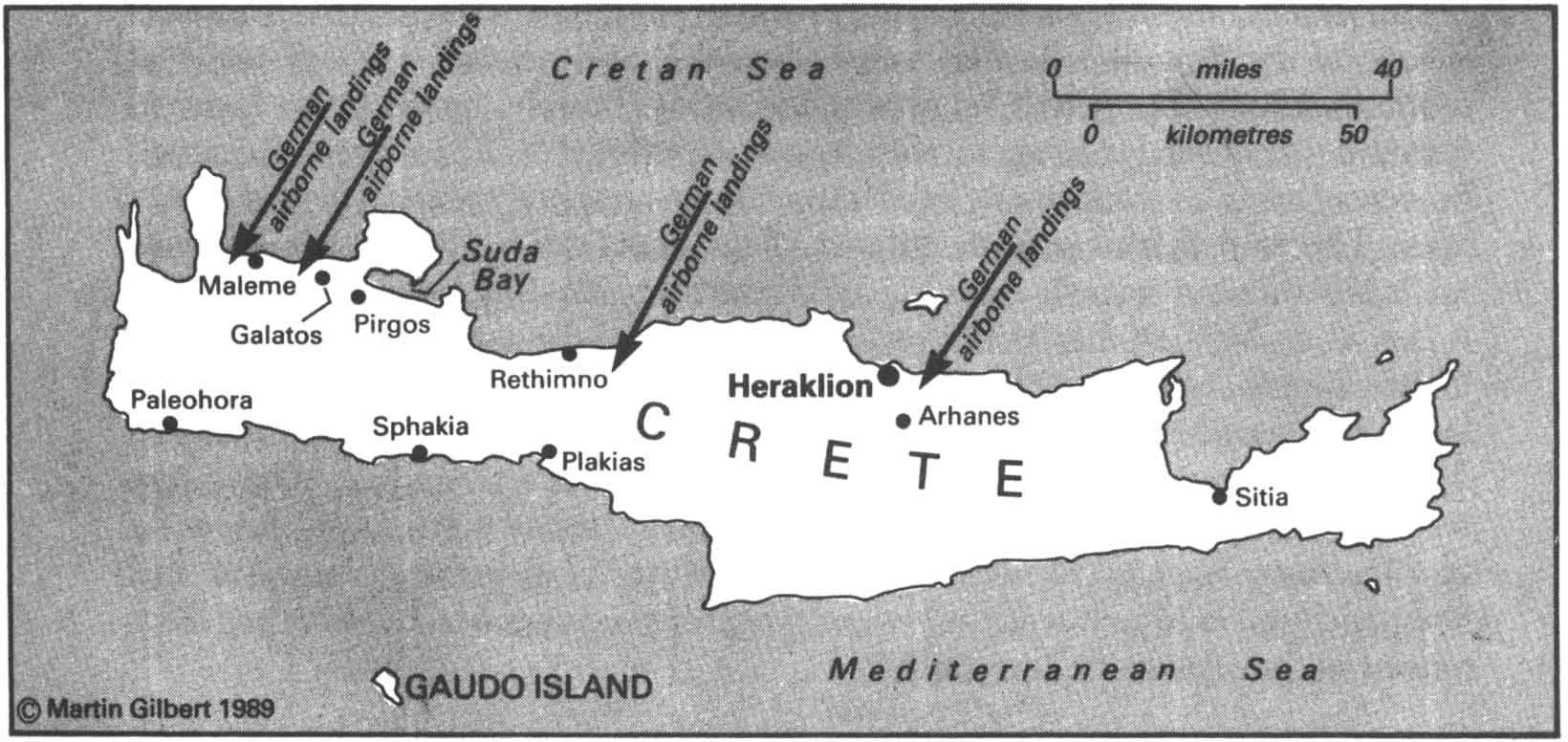

Crete, May 1941

In Moscow, Stalin was doing his utmost during April 1941 to accelerate Soviet readiness. In the third week of April, the British Military Attaché to Budapest, travelling by train to Moscow, had passed seven troop trains on the railway line between Lvov and Kiev, ‘of which four were conveying tanks and mechanized equipment, and three, troops’. This report, radioed to London by the British Military Attaché in Moscow, was intercepted by the Germans, and shown to Hitler on April 25. That day, Stalin telephoned the Russian—Jewish novelist, Ilya Ehrenburg, to say that his novel about the fall of Paris in June 1940, an event which Ehrenburg had witnessed, could now be published. He, Stalin, would help to get it passed by the censorship, which in the heyday of the Nazi—Soviet Pact, had rejected it as anti-German. ‘We’ll work together on this,’ was Stalin’s comment. Ehrenburg realized at once that Stalin’s telephone call could mean only one thing; Stalin was preparing for war with Germany. On the following day the Soviet leader was to order General Zhukov to set up five mobile artillery anti-tank brigades and an airborne corps, and to do so by June 1. One Soviet rifle corps command would also be arriving from the Soviet Far East by May 25.

April 25 saw Rommel preparing to advance still further in North Africa. ‘The battle for Egypt and the Canal is now on in earnest,’ he wrote to his wife that day, ‘and our tough opponent is fighting back with all he’s got.’ Also on April 25—for Britain, and especially for Australia, the day of the first Gallipoli landings in 1915—an armed British merchantman, the Fidelity, put ashore on the Mediterranean coast of France, at the Étang du Canet, a Pole, Czeslaw Bitner and a Maltese civil engineer, Edward Rizzo—codenamed ‘Aromatic’—who would work inside German-occupied France. Also coming ashore that night was a Belgian doctor, Albert-Marie Guérisse, who, under the name and rank of Lieutenant-Commander Patrick O’Leary, was later to operate an escape route for Allied prisoners-of-war, known to those who used it as the ‘Pat Line’, along which more than six hundred escapees were to move to safety, not only Allied aircrew and soldiers, but many Frenchmen and Belgians who wished to leave occupied Europe in order to fight in their respective forces overseas.

On April 26 Hitler left Mönichkirchen for a tour of the newly annexed regions of northern Yugoslavia, and their principal town, Maribor, renamed Marburg. That evening he travelled back to the Austrian town of Graz. ‘The Führer is very happy,’ Walther Hewel wrote in his diary, ‘a fanatical reception.’ That night, off Greece, the seven hundred survivors of a dive-bombed troop transport were dive-bombed again on the two destroyers which had rescued them, and 650 were killed. On the following day, as German troops entered Athens, the scale of the losses in the battle for Greece became clear. The Greeks had lost 15,700 men killed; the Italians, 13,755; the British Expeditionary Force, 3,712, and the Germans, 2,232; a total death toll in action of more than 35,000. Later that evening, it was learned in Berlin that Rommel’s forces had crossed into Egypt, capturing Sollum, while in the Atlantic yet more British merchant ships, and also a cruiser, had been sunk. ‘Bad days for London,’ Goebbels wrote in his diary. ‘Let us have more of them! We shall soon bring John Bull to his knees.’

Another of John Bull’s enemies struck on April 28, when Rashid Ali, who had seized power in Baghdad on April 2, sealed off the British airbase and cantonment at Habbaniya, trapping 2,200 fighting men and 9,000 civilians. The forces at Habbaniya had no artillery and, on the base, eighty-two obsolete or training aircraft. ‘Situation grave’, the base commander reported on the following day. ‘Ambassador under impression Iraqi attitude is not bluff and may mean definite promise Axis support.’

In Berlin, Ribbentrop had been urging Hitler to send aircraft and troops to Iraq. But Hitler, intent upon the destruction of the British forces in Crete, now wanted no diversion of his military resources. In a speech to nine thousand officer cadets on April 29, he declared: ‘If you ask me, “Führer, how long will the war last?” I can only say, “As long as it takes to emerge victorious! Whatever may come!”’ The word ‘capitulation’, Hitler added, was one which, as a National Socialist during the struggle for power, ‘I never knew.’ There was one word he would never know as leader of the German people and as Supreme Commander; that was also ‘capitulation’.

Military superiority was on the side of the Axis, but luck was on the side of the Allies. When, on April 29, the German Minister in Washington, Hans Thomsen, telegraphed to say that an ‘absolutely reliable source’ had revealed to him that the Americans had broken Japan’s most secret method of communications, the coded ‘Magic’ radio messages sent by Japanese ambassadors throughout the world, including Berlin, neither the Germans, nor the Japanese when alerted to the ‘alleged leak’, could believe that such a sophisticated and well-guarded Signals Intelligence code in fact could ever be broken.

German submarine successes in the Atlantic were now substantial and continuous. In April, the tonnage of Allied merchant shipping sunk had reached 394,107; a further 187,054 tons had been sunk in Greek ports during the evacuation. On April 30, in the Atlantic, the Nerissa, a troop transport, was torpedoed, and seventy-three Canadian soldiers drowned. These were the only Canadian soldiers ever lost at sea while en route from Canada to Britain. That night, a German air raid on Plymouth brought the civilian deaths that April from bombing to 6,065. ‘Hard times,’ Churchill wrote to a colleague on his return from visiting the scene of the devastation in Plymouth, ‘but the end will repay!’

While preparing to meet a German attack, Stalin did everything possible not to provoke Germany. During April his deliveries of raw materials to Germany reached their highest since the signing of the Nazi—Soviet Pact in August 1939: 208,000 tons of grain, 90,000 tons of fuel oil, 8,300 tons of cotton, 6,340 tons of copper, tin, nickel and other metals, and 4,000 tons of rubber. The rubber had been bought by Russia overseas, imported through her Far Eastern ports, and then transported to Germany by express train on the Trans-Siberian Railway. On May 1, at the May Day parade in Moscow, Stalin put the recently appointed Soviet Ambassador to Berlin, Vladimir Dekanozov, in the place of honour near him on the platform above Lenin’s tomb. That same day, the Soviet General Staff information bulletin, sent to the commanders of the Special Military Districts along the frontier, stated without prevarication: ‘In the course of all March and April along the Western Front, from the central regions of Germany, the German command has carried out an accelerated transfer of troops to the borders of the Soviet Union.’ Such concentrations were particularly visible in the Memel region, south of the Soviet Union’s most westerly naval base at Libava. The distance between the two ports was a mere sixty miles.

On May 2, as if to emphasize the imminence of danger, Richard Sorge informed his Soviet masters from Tokyo that Hitler was ‘resolved to begin war and destroy the USSR in order to utilize the European part of the Soviet Union as a raw-material and a grain base’. Sorge now reported: ‘The decision regarding the start of the war will be taken by Hitler in May.’

Hitler’s own confidence was reiterated in a speech in Berlin on May 4. ‘In this Jewish-capitalist age,’ he declared, ‘the National Socialist state stands out as a solid monument to common sense. It will survive for a thousand years.’ That day, in the Warsaw ghetto, as on every day that spring, more than seventy Jews died of starvation. In the smaller, yet equally isolated ghetto of Lodz, thirty Jews died that day; between January and June 1941, the combined death toll from starvation in both ghettos was more than 18,000.

***

On May 5 the Roumanian dictator, Marshal Antonescu, informed the Germans not only of the movement of Soviet troops westward from Siberia, and the concentration of Soviet forces around Kiev and Odessa, but also that the factories around Moscow ‘have been ordered to transfer their equipment into the country’s interior’.

German preparations for the invasion of the Soviet Union, and Soviet countermeasures were no longer being disguised. So obvious were German troop movements along the River Bug near Lvov that in the first week of May the commander of the frontier guards had asked Moscow for permission to evacuate the families of his men. Permission had been refused, and the commander rebuked for ‘panic’. Stalin himself was determined not to appear to panic; in an address on May 5 to the graduates of the Soviet Military Academies, he spoke of his confidence that the Red Army, Navy and Air Force were well enough organized and equipped to fight successfully against ‘the most modern army’. At the same time, in the version of the speech circulated by British Air Intelligence nine days later, Stalin warned that Germany had embarked on an attempt to seize the whole of Europe, and that Russia must be ready for any emergency.

‘The war is expected to start after the spring planting,’ Stalin was told by one of his own Intelligence staff that same day, May 5. Russia’s only respite was to be a German attack on Crete; also on May 5, the Enigma messages decoded in Britain confirmed that Crete was Hitler’s immediate goal.

British forces, with a substantial New Zealand contingent, and a New Zealand commander, General Freyberg, prepared as rapidly as they could to defend Crete against the Germans. Other news that day brought Britain a certain relief. On May 5 the Emperor of Abyssinia, Haile Selassie, entered his capital, Addis Ababa, five years to the day since the Italians had conquered it. Also that day, Major P. A. Cohen, who had been among several hundred British soldiers trapped in Greece, reached Crete by caïque, bringing with him 120 Australian troops who had avoided falling into German hands after Greece’s surrender.

As some men escaped from German-occupied Europe, others entered it; also on May 5, in greatest secrecy, twenty miles north of the town of Châteauroux, in Vichy France, a Frenchman working for British Special Operations, Georges Begué, parachuted successfully into the Unoccupied Zone of France, to set up a clandestine radio transmission at Châteauroux. Four days later, Pierre de Vomécourt was parachuted nearby, as the first group leader in France for the Special Operations Executive: his two brothers, who lived in France, became the first members of his group. Georges Bégue, known as George Noble, and later as ‘George One’, provided the group’s radio contact with London.

***

While Malta continued to be bombarded by German and Italian aircraft, on May 6 a second Operation Tiger saw a convoy of thirteen fast British merchant ships pass Gibraltar on their way to Egypt, eastward across the Mediterranean. Seven of the merchantmen took supplies and fuel oil to Malta, arriving without incident. In the cargo holds of the other five ships were 295 tanks and 50 fighter aircraft, urgently needed to reinforce the British troops in Egypt. During the voyage, one of the merchantmen was sunk. The remaining four, with 238 tanks and 43 fighters, reached Egypt safely.

The British had another success on May 8, when the German commerce raider Pinguin, having sunk twenty-eight merchant ships in ten months, was herself sunk in the Pacific by the British cruiser Cornwall. That same day the German submarine U-110 was captured in the Atlantic; its Commander was Julius Lemp, who had sunk the passenger liner Athenia in the first days of the war. On board his submarine the British found important cypher material which was greatly to expand Britain’s ability to read the German naval Enigma. While being towed towards Iceland, the submarine sank; its crew, including Lemp, were drowned. In the previous week, they had sunk nine Allied merchant ships.

***

On May 6, Stalin took over Molotov’s position as Soviet Premier. The German Ambassador in Moscow, von Schulenburg, in a despatch to Berlin, stressed the ‘extraordinary importance’ of this act, which was based, he said, ‘on the magnitude and rapidity of German military successes in Yugoslavia and Greece, and the realization that this made necessary a departure from the former diplomacy of the Soviet Government, that had led to an estrangement with Germany’. Stalin moved, however, to build not bridges with Germany, but to build more and effective barriers against her, ordering several reserve forces from the Urals and the River Volga to the vicinity of the River Dnieper, the western Dvina and the border areas.

On May 9, the German Air Force messages sent through the Enigma machine revealed to British Intelligence that the German troops now massing on the Soviet border would all have reached their positions by May 20. On May 10, well on time, the German Army completed Operation Otto, the development, begun on 1 October 1940, for improved rail and road facilities leading through Central and Eastern Europe to the Soviet border.

In an effort to deceive Stalin into believing that Britain, not Russia, was the real object of his invasion plans, and that German troops were only moving east to escape British bombing reprisals, Hitler now embarked upon a renewed bomber offensive against Britain. Every night during the first two weeks of May, British cities and docks were pounded from the air. Once on the night of May 8, British radio counter-measures succeeded in bending the signal beam along which German bombers flew to their targets, and 235 high explosive bombs, intended for an aircraft engine factory at Derby, were dropped on empty fields more than twenty miles away. In a bombing raid on Clydeside, however, fifty-seven civilians were killed, and, in the Liverpool docks, thirteen merchant ships were bombed and sunk in seven nights of bombing. ‘I feel that we are fighting for life, and survive from day to day and hour to hour,’ Churchill told the House of Commons on May 7, ‘but believe me, Herr Hitler has his problems too.’

That night, in a German bombing raid on Humberside, twenty-three German aircraft were shot down by British fighters and anti-aircraft fire. But Hitler’s problems that week were not to be measured in terms of aircraft lost, for on May 10, like a bolt from the blue, the Deputy Leader of the Nazi Party, Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s colleague and confidant for nearly twenty years, flew across the North Sea in a dramatic and risky solo dash, and parachuted into Britain, landing near the village of Eaglesham, in Scotland.

Hess claimed that he had come to make peace between Britain and Germany. He revealed nothing about Hitler’s plans to invade the Soviet Union. Indeed, under interrogation he insisted that there was ‘no foundation for the rumours now being spread that Hitler is contemplating an early attack on Russia’. The official Nazi announcement declared that Hess was suffering from ‘a mental disorder’. This was also the view of those who interrogated him in Britain. That night, May 10, in another German air raid, London was again struck, and the Houses of Parliament badly damaged; the debating chamber of the House of Commons was completely destroyed. On the following morning, a third of the streets in central London were found to be impassable; 1,436 civilians had been killed, more than in any other single raid on Britain.

The air raid on May 10 marked the last raid of the ‘Spring’ Blitz of 1941. Londoners were apprehensive that morning, as they had not been since the previous December. They could not know that Hitler now had other work for his bombers to do. The time for deception was over; the time for action had almost come.

***

Since April 17, Yugoslavia had ceased to exist as an independent State; in German-occupied Serbia, Italian-occupied Dalmatia, Bulgarian-occupied Macedonia, the Hungarian-occupied Banat, and the newly independent Croatia, the bonds of tyranny and persecution had begun. Serbs and Jews were the principal victims, also democrats and liberals; for all of them, forced labour in concentration camps, and random killings, became the daily dangers of life under occupation. On May 7, fleeing southwards from the Croat capital of Zagreb, a forty-nine-year-old Communist, a veteran of the Spanish Civil War, set up in Belgrade the nucleus of a Communist revolt. Known to Stalin as ‘Valter’, his real name was Josip Broz, and his alias in occupied and partitioned Yugoslavia, Tito.

Four days after Tito left Zagreb for Belgrade, a former officer in the Yugoslav Army, Colonal Draža Mihailović, established himself as a focus of revolt on the plateau of Ravna Gora, in Western Serbia.

The forces of Mihailović, like those of Tito, were to fight against the Germans and eventually make much of Serbia and Bosnia ungovernable. But Mihailović was also a bitter opponent of Communist aspirations, collaborated with the Italians, and tried to preserve his forces by avoiding conflict with the Germans, so much so that after two years the British were to switch their military support from the Četniks to the Communists.

***

In the second week of May, Hitler sent two bombers to Iraq to help Rashid Ali maintain his revolt against Britain. On May 12, a German Air Force officer, Major Axel von Blomberg, reached Baghdad to act as a liaison officer with Rashid Ali. Arriving over the Iraqi capital in the middle of a dogfight between British and Iraqi fighters, von Blomberg was shot dead by a stray British bullet.

On May 12, the Japanese Ambassador in Baghdad sent a report to Tokyo to say that Rashid Ali’s resistance could continue for no more than three to eight days. If, however, British forces were to advance from Palestine as well as from Basra, the Ambassador believed that the Iraqi Army would collapse even sooner, and abandon Baghdad. This message, picked up by British Intelligence and at once decrypted, was sent by Churchill to the Commander-in-Chief, Middle East. On May 13 another special force, consisting of Arab troops from the Arab Legion and the Transjordan Frontier Force, crossed the Transjordanian frontier into Iraq. ‘Will the Arab Legion fight?’, General Wilson, commanding in Palestine, asked the Legion’s commander, Major Glubb. ‘The Arab Legion will fight anybody,’ Glubb replied. Five days later, an advance column of Glubb’s troops, having crossed three hundred miles of desert, reached Habbaniya. But a squadron of the Transjordanian Frontier Force did mutiny on the way, claiming that they had ‘no quarrel with the Iraqis’ and that the British ‘made others fight for them’.

Crete, May 1941

***

For many months, the death toll in Britain from German bombing had been reduced by the dedicated and dangerous work of special Unexploded Bomb Disposal Squads. The death toll among these squads was high. One such squad was made up of the Earl of Suffolk—who in June 1940 had brought the heavy water and the nuclear scientists from France—his secretary Miss Morden and his chauffeur Fred Hards; they were known in the bomb disposal world as the Holy Trinity. On May 12, at Erith in Kent, they were trying to defuse their thirty-fifth bomb when it exploded, and they were blown to pieces. The Earl was awarded a posthumous George Cross.

In Europe, the German plans for action against Russian Communists, and other civilians, reached a decisive point on May 12, when a German Army briefing agenda stated that high-ranking political officials and leaders ‘must be eliminated’. General Jodl noted in the margin of this briefing: ‘We can count on future reprisals against German pilots. Therefore, we shall do best to organize the whole action as if it were an act of reprisal.’

In Poznan, in German-annexed Poland, the local newspaper announced on May 14 that three Poles, Stanislaw Weclas, Leon Pawlowski and Stanislaw Wencel, had been sentenced to death for an alleged anti-German conspiracy. ‘Everyone who believes in resistance’, the report declared, ‘will be destroyed.’

***

On May 14 the Germans began the massive air bombardment of Malta. Not aware that the British knew from the Enigma intercepts that Crete was their true invasion target, they sought to give the impression that it was Malta that was about to be attacked. The bombardment was ferocious; sixty-two German and fifteen Italian aircraft were shot down, but the British lost sixty fighters, half of them destroyed on the ground, losses that could not easily be replaced.

On May 15, nine days after learning from the Enigma intercepts that Rommel’s forces on the Egyptian border were exhausted, and needed time for rest and reorganization, the British launched Operation Brevity, against the forward German positions, forcing a withdrawal from the Halfaya Pass. Rommel, however, by an extraordinary exertion, counter-attacked in strength two weeks later. The British, aware from Enigma of the exact size and direction of Rommel’s advance, withdrew, avoiding an unnecessary clash of arms.

It was on May 15 that Hitler ordered the start of the aerial bombardment of Crete, in preparation for the invasion five days later. That day, Richard Sorge, in Tokyo, sent his Soviet masters in Moscow a radio message giving them the date of the German invasion of Russia—between June 20 and 22. That same week, Soviet reinforcements both from the North Caucasus and from the Soviet Far East were ordered to take up positions in the West, between Kraslava and Kremenchug. So urgent was their westward transfer judged to be that they were moved without arms or equipment.

***

The needs of German pilots on the Eastern Front were the reason given by Dr Sigmund Rascher, a German Air Force staff surgeon, in a letter to Himmler on May 15, asking permission to use concentration camp inmates from Dachau for experiments in atmospheric tests. These tests, Dr Rascher explained, were needed in order to find out the limits of the oxygen needs of German pilots, and their possible endurance to atmospheric pressure. Rascher also wrote of his ‘considerable regret that no experiments on human beings have so far been possible for us because the experiments are very dangerous and cannot attract volunteers’. Two or three ‘professional criminals’ from Dachau would, he said, suffice. Himmler approved of this request.

***

On May 19, following the destruction of twenty-nine of the thirty-five British fighters on Crete, the six remaining fighters were transferred to Egypt. It was felt that there was no point in sacrificing them, in view of Germany’s overwhelming air superiority. On the following morning, May 20, at 5.30 a.m., a violent German air attack was launched again against the two main airfields, at Maleme and Heraklion; an hour and a half later, in a second air attack, both airfields were completely immobilized. Then, as the second wave of bombers returned to Greece, the first wave of German airborne forces, commanded by General Kurt Student, were flown to the island in 493 transport planes. Only seven of the planes were shot down by anti-aircraft fire.

In the first day’s battle, the forces defending Crete, 32,000 British, Australian and New Zealand troops, and 10,000 Greeks, succeeded, despite a second paratroop landing in the afternoon, in holding the airfields at Maleme and Heraklion. Two convoys of German troops, sent by sea from Piraeus and Salonica, many of them in fishing boats, were badly mauled by British naval forces, the second of the convoys being forced to turn back. By nightfall, it looked as if the invasion had failed. Indeed, of the three German regimental commanders of the airborne landings, Lieutenant-General Süssman was killed when his glider crashed and Major-General Meindl was seriously wounded.

During the night, however, the Germans succeeded in capturing Maleme airfield, enabling them to fly in reinforcements of men and weapons on the afternoon of May 21; in a final, unsuccessful attempt to recapture the airfield, a New Zealander, Second Lieutenant Charles Upham was awarded the Victoria Cross. Two other Victoria Crosses were awarded on Crete: one was won by a New Zealand sergeant, Clive Hulme, who having received news that his brother had been killed in the battle, single-handed killed thirty-three Germans; the other Victoria Cross was won by a British sailor, Petty Officer Alfred Sephton. Although previously wounded by machine gun fire as his ship, the Coventry, sought to rescue the hospital ship Aba from a ferocious dive-bombing attack, Sephton continued to direct his ship’s anti-aircraft fire until the attacking aircraft were driven off. Lieutenant Upham was later to win a second Victoria Cross in the Western Desert, the only British or Commonwealth serviceman to be awarded it twice in the Second World War.

Neither the bravery of individuals, nor the tenacious courage of the troops as a whole, could successfully resist the overwhelming air and eventually land power of the German forces. On May 22, German dive-bombers sank the cruisers Fiji and Gloucester, and four destroyers. Several of the survivors of the Gloucester had been machine-gunned from the air while clinging to wreckage. The ship’s captain, Henry Aubrey Rowley, was among the 725 dead. Four weeks later, his body was washed ashore near Mersa Matruh. Commented Admiral Cunningham: ‘It was a long way to come home.’

Among the warships damaged but not sunk on May 22 was the battleship Valiant, with Midshipman Prince Philip of Greece on board; on one occasion, as he recorded in his log, she was attacked by fourteen dive-bombers. The ship was hit, however, by only two small bombs. Prince Philip’s uncle, Captain Lord Louis Mountbatten, was less fortunate; on May 23 his destroyer, Kelly, was attacked by twenty-four dive-bombers, and sunk; 130 of her crew were killed. Although still on the bridge when his ship turned over, Mountbatten was able to swim clear, whereupon he proceeded to take charge of the rescue operation.

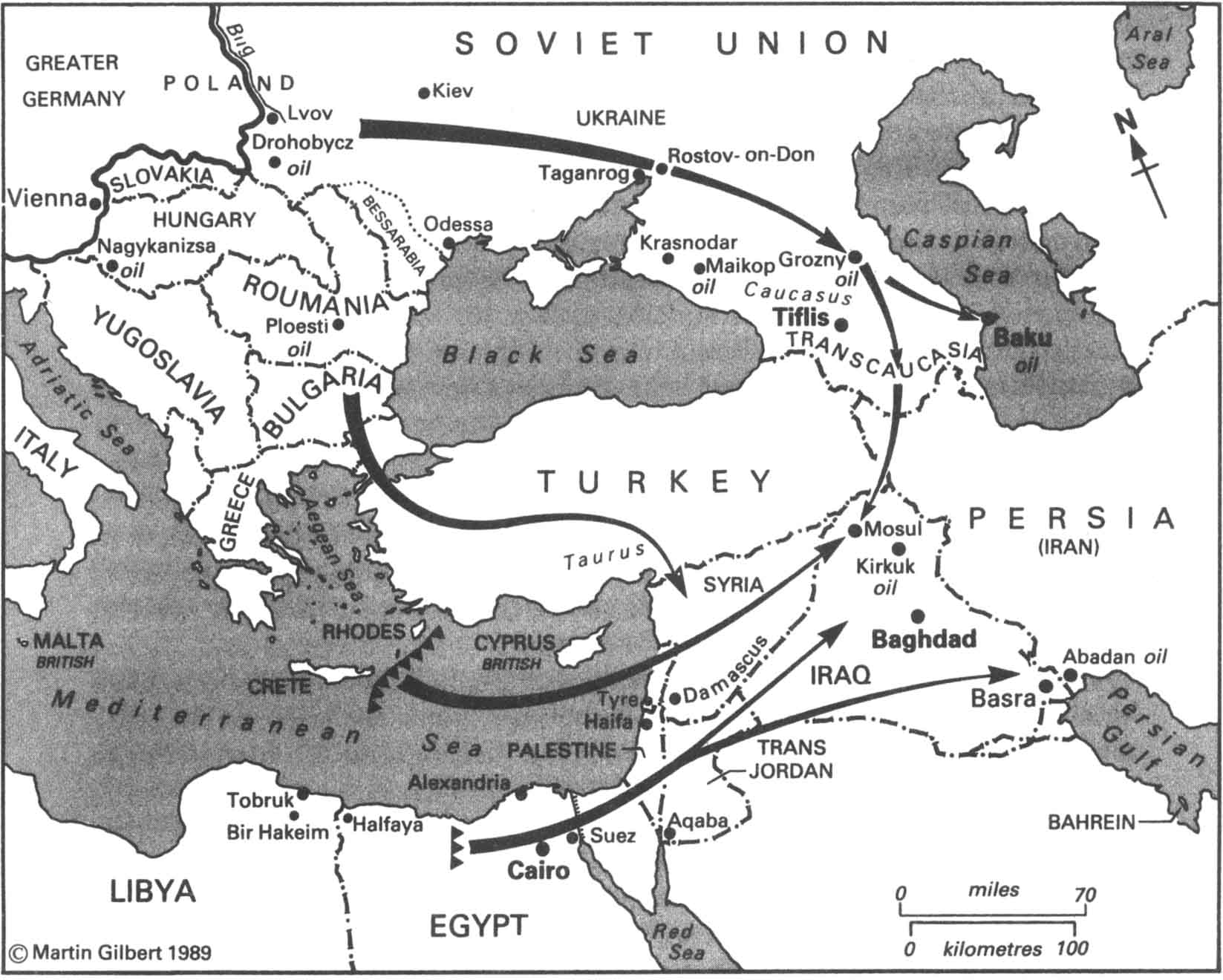

On May 23, as the battle continued both on land and at sea, the Germans were able to reinforce their men on Crete with mountain troops. It seemed, especially in Berlin, that all was lost for Britain, not only on Crete, but throughout the eastern Mediterranean, should Hitler choose to follow up his success. But on May 23, with his battle for Crete still being fought, Hitler issued his Directive No. 30, in which he made it clear that the decision whether or not to launch an offensive to ‘break the British position’ between the Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf, or on the Suez Canal, ‘will be decided only after “Barbarossa”’.

Even as the battle for Crete reached its final forty-eight hours, the British had a naval disaster in the distant Atlantic. On May 18 the battleship Bismarck, commanded by Admiral Lütjens, and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen had sailed into the North Atlantic. Six days later, on May 24, the Bismarck sank the British battle-cruiser Hood, only three of whose crew of 1,500 survived. That same day, guided by intercepted Italian radio messages, a British submarine sank the Italian liner Conte Rosso, with 1,500 Italian troops on board; it was on its way to reinforce the Italian troops in Libya.

On Crete, the British defenders continued throughout May 25 to resist the German advance, counter-attacking at Galatos with no fewer than twenty-five bayonet charges. That day, King George of the Hellenes, who had been evacuated from Athens to Crete, was evacuated again, with his Ministers, to Egypt. On May 27, near Pirgos, Australian and New Zealand troops succeeded, for a while, in driving the Germans back. But it was clear that the battle for Crete was lost. Several units were now without ammunition. During the day, General Freyberg drew up plans to evacuate the island; the evacuation began that same evening.

Even as the bad news from Crete reached Britain, news of a naval success raised morale; for on May 27 the German battleship Bismarck was attacked in the Atlantic by a ring of British warships; damaged and burning, she was unable any longer to fight or to escape. Admiral Lütjens gave orders for his ship, the pride of the German navy, to be scuttled. A hundred men were picked up by two British warships, Dorsetshire and Maori, but a German submarine alarm caused both captains to abandon their rescue work and move away at full speed. Hundreds of German sailors, desperately trying to cling to the side of their would-be rescue vessels, were cut to pieces by the churning propellers.

In all, 2,300 German sailors were drowned; Lütjens went down with his ship. ‘She had put up a most gallant fight against impossible odds,’ the British naval commander, Admiral Tovey, wrote in his official report of the action, ‘worthy of the old days of the Imperial German Navy. It is unfortunate that “for political reasons” this fact cannot be made public.’ The news of the loss of the Bismarck was received in Berlin with disbelief. ‘Mood very dejected,’ Walther Hewel wrote in his diary. ‘Führer melancholy beyond words.’

Hitler had further cause to be melancholy on May 27, when Roosevelt, in one of his radio ‘Fireside Chats’, announced that United States naval ports ‘are helping now to ensure the delivery of needed supplies to Britain’, and that ‘all additional measures’ necessary for the delivery of these goods would be taken. ‘The delivery of needed supplies to Britain is imperative,’ Roosevelt declared. ‘This can be done. It must be done. It will be done,’ and he added, in words which were to inspire all the Western combattants and subject peoples: ‘The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.’

In a telegram of appreciation to Roosevelt, King George VI declared that the President’s announcement ‘has given us great encouragement, and will I know stimulate us all to still greater efforts till the victory for freedom is finally won’.

‘…is finally won’; on Crete, the embarkation of British troops began on the following night, May 28, and was to continue until the night of June 1. As the British left from the small south-eastern ports of Sphakia, Paleohora and Plakias, the Italians landed 2,700 men at Sitia, on the eastern end of the island.

As the evacuation continued, German dive bombers sank the anti-aircraft cruiser Calcutta and damaged several other warships. When the flagship Orion was dive-bombed on May 29, she had 1,090 passengers on board; 262 of them were killed.

In five nights, 17,000 men were taken off Crete, most of them from open beaches during the few short hours of darkness. Five thousand men, separated from their units and scattered about the island, had to be left behind. The Germans had lost 1,990 men killed in action. The British and Commonwealth forces, 1,742. A further 2,265 British and Commonwealth sailors had been killed at sea.

***

On May 27, as the British troops on Crete had begun to prepare the evacuation, Rommel captured the Halfaya Pass. His troops, having taken 3,000 prisoners and 123 guns, now stood where earlier the Italians had stood, at the gateway to Egypt. That same day, at Bir Hakeim, in the Libyan desert, a French Foreign Legion force, together with Free French soldiers who included among their numbers Bretons, Tahitians, Algerians, Moroccans, Lebanese, Cambodians, Mauritians and men from Madagascar and Chad, who had been besieged for more than a week, were attacked by Italian troops. Their attackers were driven off. ‘We were told we could crush you in fifteen minutes,’ the captured Italian commander of the attack, Colonel Prestissimo, told his captors. The French were understandably confident, all the more so when, in the following days, in the desert around Bir Hakeim, a young French captain, Pierre Messmer, held up fifteen German tanks which had hoped to succeed where the Italian troops had failed.

Messmer was later to become Prime Minister in post-war France. The ‘glittering courage’ of the defenders of Bir Hakeim, as one historian has called it, was to be remembered and honoured in France for many years to come. But after fifteen days the siege was ended by a mass breakout back to the British lines, and one more desert outpost came under Rommel’s control. In the breakout, seventy-two French soldiers were killed, but 2,500 reached safety.

The British were now back in Egypt, their gains in Libya lost, and the defence of the Suez Canal once more a matter of urgency. Fortunately for them, the withdrawal from Libya coincided with the surrender of Rashid Ali in Iraq. Neither Germany nor Italy had been prepared to send more aircraft; on May 28 the British had learned from coded Italian radio messages that no further Italian air support would arrive, because of shortage of fuel. Two days later, on May 30, the Mayor of Baghdad and the army officers loyal to Rashid Ali, who were still holding out in the capital, asked for an armistice. The British triumph, however, was somewhat marred three days later, when supporters of Rashid Ali rampaged through the Jewish quarter of Baghdad, looting shops and houses, and killing their inhabitants; when the rampage was over, more than 150 Jews had been killed.

The last eleven days of May had seen the kaleidoscope of war in all its complexity: a defeat for Britain on Crete; a disaster for Germany at sea; a victory for Germany in the Western Desert, the collapse of a pro-Axis revolt in Iraq, and the murder of Jews. In German-occupied Europe, those same eleven days had also seen several manifestations of the darkest side of Nazism. Beginning on May 20, steps had been taken in both German-occupied France and Belgium to halt the emigration of Jews to neutral Portugal, and from there to the United States. Such emigration, though difficult, had enabled several thousand Jews to leave German-controlled territory during the previous twelve months. Now Walter Schellenberg, acting for Heydrich, sent a circular to all the departments of the German Security Police, and to all German consulates, informing them that Jewish emigration was henceforth forbidden, ‘in view of the undoubtedly imminent final solution of the Jewish question’. What this ‘final solution’ might be, Schellenberg did not explain; but it was clear that it did not envisage the departure of Jews to safe or neutral lands.

A clearer picture of the ‘Final Solution’ had been given by Himmler, in late May, to 120 Special Task Force leaders, meeting at the Frontier Police School at Pretzsch, on the River Elbe. These officers had been chosen to command three thousand armed men who would follow in the wake of the German armies as they advanced across Russia. The task in hand, Himmler explained, was to train ‘for their annihilation campaign against the racial enemy’. On June 1, at a further briefing by Heydrich, the task force commanders were told that the ‘eastern Jews’ were the ‘intellectual reservoir of Bolshevism’ and, ‘in the Führer’s view’, were to be liquidated.

From every corner of German-occupied Europe, troops were now being moved to the East. On June 3, the SS Death’s Head Division left Bordeaux, travelling for four days and nights across France and Germany, to Marienwerder in East Prussia. In all, between January and June 1941, 17,000 trains had conveyed German troops towards the borders of Russia: on average more than a hundred trains a day.

As Hitler prepared to invade Russia, another German who had embarked upon a war in the East died in exile in Holland; the former Kaiser, Wilhelm II. In May 1940, after having turned down Churchill’s offer of refuge in England, he had declined Hitler’s offer to return to Germany as a private citizen, to live on one of his former royal estates in Prussia. Wilhelm’s war with his cousin, the Russian Tsar, had led to the destruction of both their empires. Hitler, with his own invasion of Russia now little more than two weeks away, was confident that in the renewed clash of the German and Russian forces, it was Russia that would now be destroyed.

On June 6, two days after the death of the Kaiser, Hitler instructed General von Brauchitsch to issue the Commissar Decree to all commanders. Two days later, the first units of a German infantry division landed in Finland, whose leader, General Mannerheim had agreed to participate in the new conflict. On June 11, in a discussion with the Roumanian leader, Marshal Antonescu, Hitler said that while he was not asking for Roumanian assistance he ‘merely expected of Roumania that in her own interest she do everything to facilitate a successful conclusion of this conflict’. Antonescu, who, unlike the Hungarians, Italians and Bulgarians, had gained nothing from the German conquest of Greece, accepted with alacrity this invitation to regain the lost province of Bessarabia, and to gain new territory, in the East.

***

At two o’clock on the morning of June 8, British and Free French forces entered Syria and the Lebanon. This was Operation Exporter, the plan to overthrow the French garrisons loyal to Vichy France, and to raise the Free French flag over Beirut and Damascus. The 45,000 defenders of the garrisons, commanded by General Dentz, put up a strong resistance, which was to last for more than five weeks. Among those wounded in the first days was a Palestinian Jewish volunteer, the twenty-six-year-old Moshe Dayan, who lost an eye. During the decisive first three weeks of the battle, 18,000 Australian, 9,000 British, 5,000 Free French and 2,000 Indian troops took part in the advance, as well as several hundred Palestinian Jews. On July 9, British troops entered the Lebanese port city of Tyre.

Germany and the Middle East, the German plan of 11 June 1941

***

The German invasion of Russia was less than two weeks away; on June 9 General Halder visited the German Fourth Army to discuss special measures for ‘surprise attack’—artillery, smoke-screens, rapid movement and the evacuation of Polish civilians from the operational zone. On June 10—the 751st anniversary of the drowning of the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa in 1190, the day on which, according to legend, the dead Frederick began to await his countrymen’s call to lead them back to glory—the Germans put into effect Operation Warzburg, a ten day programme of minelaying in the Baltic, designed to prevent the Russian Baltic Fleet from escaping through the Kattegat into the North Sea. On the following day, June 11, in Directive No 32, Hitler laid down his plans for the German Army, Navy and Air Force ‘After the destruction of the Soviet armed forces’.

Hitler’s plans were wide-ranging. Operation Isabella would secure the Atlantic coastline of Spain and Portugal. The British would be driven from Gibraltar, with or without Spanish help. Strong pressure would be exerted on both Turkey and Iran to make direct or indirect use of them ‘in the struggle against England’. The British would be driven from Palestine and the Suez Canal by ‘converging attacks’ launched from Libya through Egypt, and from Bulgaria through Turkey. Meanwhile, ‘it is important that Tobruk should be eliminated’; the attack on the besieged fortress should be planned for November. If the ‘collapse of the Soviet Union’ had created the ‘necessary conditions’, preparations would also be made for the despatch of a German expeditionary force from Transcaucasia against Iraq. By using the Arabs, the position of the British in the Middle East would, Hitler added, ‘be rendered more precarious, in the event of major German operations, if more British forces are tied down at the right moment by civil commotion or revolt’.

Quite apart from these Middle Eastern and Mediterranean operations, there was, Hitler wrote, another objective to be borne in mind: ‘the “Siege of England” must be resumed with the utmost intensity by the Navy and Air Force after the conclusion of the campaign in the East’.

This directive made it clear how much depended upon Germany’s victory over Russia. That night, as if to mock at these sentiments, British bombers struck at industrial targets in the Ruhr, the Rhineland and the German North Sea ports, and continued to do so for twenty consecutive nights. In France, British Special Operations agents continued their work in setting up escape lines for prisoners of war, and in making contact with Frenchmen who did not wish to remain passive under the German occupation. ‘We shall aid and stir the people of every conquered country to resistance and revolt,’ Churchill told the British people in a broadcast on June 12. ‘We shall break up or derange every effort which Hitler makes to systematize and consolidate his subjugation. He will find no peace, no rest, no halting place, no parley.’

On June 14, as Hitler and his commanders made their final plans for the invasion of Russia, now only eight days away, Roosevelt took another step in the direction of substantial help for Britain, freezing all German and Italian economic assets in the United States. He also accepted Churchill’s request for the United States to take over the defence of Iceland, which Britain had been occupying since the defeat of Denmark in April 1940. Substantial American arms were also on their way to the British forces in Egypt, in seventy-four merchant ships, thirty of which were flying the American flag. Among their cargoes were two hundred American tanks from United States Army production.

Two days after Churchill’s broadcast, one of the heroes of the high summer of 1940, John Mungo Park, a Spitfire pilot, was killed in action over France. Nor was it only towards those States already under German rule that Britain directed her support. On June 13, in a serious attempt to show the Soviet Union that she would not be left to fight Hitler alone, Churchill offered to send Stalin a British military mission in the event of a German attack. It would seem, however, that Stalin considered this offer a provocation, part of a British scheme to precipitate him into the war against Germany. His reaction was similarly suspicious when Churchill sent him details about the German divisions concentrating on the Soviet frontier; these details had once again been culled from the Germans’ own top secret Enigma messages. It was also on June 13 that Admiral Kuznetsov, the Soviet Navy Commissar, visiting Stalin in the Kremlin, failed to arouse his concern about recent German naval movements, or to elicit from him a request to prepare the Soviet naval forces for action.

Among the most secret messages decrypted by British Intelligence at Bletchley on June 14 were German orders sent in connection with the arrival of a ‘Chief War Correspondent’ at Kirkenes, in northern Norway, near the border with Russia. At the Kremlin that day, Timoshenko and Zhukov found Stalin apparently little concerned by the German military build up. When they pointed out that according to Soviet Intelligence reports the German divisions now on the border were ‘manned and armed at wartime strength’, Stalin’s comment was: ‘You can’t believe everything Intelligence says.’ During this meeting, the discussion was interrupted by a telephone call to Stalin from the Communist Party boss in the Ukraine, Nikita Khrushchev. ‘Stalin picked up the phone,’ Zhukov later recalled. ‘We gathered from his replies that the call concerned agriculture. “Fine,” Stalin said, and smiled. Evidently, Khrushchev had reported in glowing terms about the good prospects of a bumper crop.’

‘We left the Kremlin’, Zhukov added, ‘with a heavy heart.’ For the heads of German Intelligence, however, it was the continuous Soviet troop movements that were ominous; Russian troops brought westward into European Russia in the previous month had raised the Soviet strength to 150 rifle divisions, 7 armoured divisions, and 38 armoured brigades.

That day, June 14, in East Prussia, the commanding officer of the SS Death’s Head Division, General Eicke, informed his commanders of the content of Hitler’s Commissar Decree. The war with Russia, Eicke explained, must be fought as an ideological war, a life-and-death struggle between National Socialism and ‘Jewish Bolshevism’. Political commissars attached to Red Army units were ‘to be killed immediately after their capture or surrender, regardless of the circumstances’. The Division must be ‘fanatical and merciless’. Russia had not signed the Geneva Convention, and therefore ‘could not be expected to wage war in a civilized fashion’. The men in the Death’s Head Division would therefore be expected to fight ‘without mercy or pity’. The war in the East was a struggle ‘upon which the fate of the German people depended’.

Hitler’s fanaticism had now been communicated to the men who would have to put it into practice. That same day, in a final briefing for his senior commanders, Hitler warned that the Russian forces outnumbered the Germans, but that German leadership, equipment and experience were superior. At the same time, he warned them not to underestimate the Red Army. He also, echoing his Directive of three days earlier, told them: ‘The main enemy is still Britain. Britain will fight on as long as the fight has any purpose….’

On June 15, the British forces in Egypt launched Operation Battleaxe, an attempt to drive Rommel back through Libya, and possibly even to relieve Tobruk. ‘I naturally attach the very greatest importance to the venture,’ Churchill telegraphed to Roosevelt on the eve of the attack. But the operation was seriously handicapped by its inferior equipment, and after an initial advance could make no real headway against Rommel’s tanks and armoured cars. British Intelligence had judged the time and scale of Rommel’s counter-attack correctly: the British forces simply did not have the strength to meet it. During four days of battle, 122 British troops were killed and a hundred British tanks lost.

On the day that Operation Battleaxe was launched from Egypt, all German commanders in the East, as ordered on the previous day, completed their preparations to launch the attack. They now awaited only one of two code words: ‘Altona’—postponement or cancellation, or ‘Dortmund’—proceed. That same day, the Soviet commander in Kiev, General Kirponos, convinced that war was imminent, sent Stalin by messenger a personal letter, asking for permission to evacuate 300,000 Soviet civilians from the frontier region along the River Bug, and to set up anti-tank barriers. Stalin replied, as he had to similar requests that week: ‘This would be a provocative act. Do not move.’

In Germany’s Army Group Centre, on June 15, a list of bombing targets was issued, each of which was to be destroyed in the opening hours of the assault: among them were the Red Army’s communications posts and signals centres set up in the former eastern regions of Poland, at Kobryn, Volkovysk, Lida, and Baranowicze, as well as those east of the former Russo-Polish frontier, at Slutsk, Minsk, Mogilev, Orsha and Smolensk.

In Berlin, on June 15, fantastic rumours spread, ‘that an understanding with Russia is imminent’, as the diplomat Ulrich von Hassell noted in his diary, and that ‘Stalin is coming here, etc.’ But in London, Churchill’s daily reading of the Germans’ own Enigma radio messages made it clear that a German invasion of Russia was only a matter of days. ‘From every source at my disposal, including some most trustworthy,’ he telegraphed to Roosevelt on June 15, ‘it looks as if a vast German onslaught on Russia is imminent. Not only are the main German armies deployed from Finland to Roumania, but the final arrivals of air and armoured forces are being completed.’ Should this new war break out, Churchill added, ‘we shall of course give all encouragement, and any help we can spare, to the Russians following the principle that Hitler is the foe we have to beat’.

In an appeal which he broadcast to the American people on the following night, June 16, Churchill tried to give expression to his sense of urgency, and of foreboding. ‘Every month that passes’, he warned, ‘adds to the length and to the perils of the journey that will have to be made. United we stand, divided we fall. Divided, the dark ages return. United, we can save and guide the world.’

In the United States, two days after Churchill’s broadcast, Roosevelt received Colonel William J. Donovan, whom he appointed Co-ordinator of Information, with the duty to collect and analyse all information bearing on national security, to ‘correlate such information and data’, and to make it available to the President. Donovan was also entrusted with the conduct of special questions and subversive propaganda.

On the day of Churchill’s broadcast, the last German warship in the Soviet waters of the Black Sea had sailed away. Of the twenty German engineers still working in Leningrad in May, the last one had already gone by June 15. Those signs of an impending German onslaught were seen by Soviet naval observers, and reported to the commander of the Soviet Baltic Fleet, Admiral Tributs. On June 17, in tightest secrecy, all German military, naval and air commanders received the coded radio message, ‘Warzburg’: the attack on Russia was to begin at three in the morning of Sunday June 22. On the following day at noon, Soviet Frontier troops in Bialystok were put on alert.

The German leaders and ideologues were confident of victory; on June 18, Alfred Rosenberg completed his plans for the breaking-up of the Caucasus mountain region of the Soviet Union into a series of five separate German-administered ‘General Commissariats’ in Georgia, Azerbaidjan, North Caucasus, Krasnodar and Ordzhonikidze, and two ‘Main Commissariats’ for Armenia and the Kalmyk area. By such means, Rosenberg believed, Germany would control a Berlin—Tiflis axis friendly to Germany, and a permanent barrier to any future resurgence of Russian power.

In preparation for the imminent struggle, on June 19 the SS issued special regulations, establishing a welfare fund for the care of orphans and widows of SS men killed in action. But did the Red Army appreciate that an onslaught was imminent? On June 19 the Soviet Minister of Defence, Marshal Timoshenko, ordered the camouflaging of forward airfields, military units and installations, many of which were still plainly visible both from the ground and from the air. That same evening, in a telephone call from Leningrad to Moscow, Admiral Tributs, after reporting on the final departure on June 16 of the last German warship in Soviet waters, obtained permission from Admiral Kuznetsov, the Minister of the Navy, to bring the Baltic Fleet up to ‘Readiness No. 2’, the fuelling of all Soviet warships and putting their crews on alert. Also in Leningrad, however, June 19 saw the departure of the Secretary of the Regional Party Committee, Andrei Zhdanov, the Soviet Party boss in the city, and a member of Stalin’s Military Council, for his summer holiday at the resort of Sochi, on the Black Sea. As Zhdanov left for his holiday, Admiral Kuznetsov also put the Soviet Black Sea Fleet on ‘Readiness No. 2’.

In the Middle East, the early hours of June 21 saw the surrender of the Vichy forces in Damascus to the combined British and Free French expedition. Hitler had now lost any chance of an easy descent on Palestine and the Suez Canal. That same night, on the East Prussian—Lithuanian frontier, near Buraki, a group of German soldiers on reconnaissance mission tried to cross into the Soviet lines. Three were killed and two were captured. At 2.40 that morning, the Chief of Staff of the Western Special Military District, General Klimovskikh, radioed to Moscow from his headquarters at Panevezys, that ‘German aircraft with loaded bomb racks’ had violated the frontier on the previous day, west of Kovno, and, even more ominously, according to the report of one of his Army commanders, that the wire barricades along the frontier on the Augustow and Siena roads, though in position during the day, ‘are removed towards evening’. General Klimovskikh added: ‘From the woods, sounds of engines.’

At four in the morning, a submarine commander in the Red Navy, Captain Marinenko, reported sighting a convoy of thirty-two German troop transports at the entrance to the Gulf of Finland. Admiral Tributs was duly informed, and was alarmed. Ten hours later, at two o’clock that afternoon, Stalin himself telephoned from the Kremlin to the commander of the Moscow District, General Tiulenev, to tell him that ‘the situation is uneasy’, and instructing him to ‘bring the troops of Moscow’s anti-aircraft defence to seventy-five per cent of combat readiness’. A similar instruction was telephoned shortly afterwards to Nikita Khrushchev in Kiev. Once more, it was Stalin himself on the line.

On the afternoon of June 21, Hitler wrote to Mussolini that he had made ‘the hardest decision of my life’.

Shortly after nine o’clock that evening, the Chief of Staff of the Kiev Military District, General Purkayev, telephoned to Marshal Zhukov in Moscow, to inform him that a German sergeant-major ‘had come to our frontier guards and said that German troops were moving to jumping-off areas and that the attack would begin in the morning of June 22’. The deserter was Alfred Liskof, who had given himself up at the Ukrainian border town of Vladimir-Volynsk.

Zhukov telephoned at once to Stalin, who summoned him and Timoshenko to the Kremlin. ‘The German generals may have sent this turncoat to provoke a conflict,’ Stalin told them. ‘No,’ replied Timoshenko, ‘we think he is telling the truth.’ ‘What are we to do?’, Stalin asked, to which Timoshenko replied: ‘A directive must immediately be given to alert all troops in the border districts.’

Stalin still hesitated. ‘It’s too early’, he replied, ‘to issue such a directive—perhaps the question can be settled peacefully.’ He did agree, however, to a directive to all Military Councils in the frontier districts warning them that ‘a sudden German attack is possible’. Stalin added, however, that the Soviet troops must not be ‘incited by any provocative action’ by the Germans. The directive, as signed that night by Timoshenko and Zhukov, ordered the firing posts in the Fortified Areas to be ‘secretly manned’ in the early hours of June 22; for all aircraft to be dispersed ‘before dawn’ on June 22 among field aerodromes ‘and carefully camouflaged’; for ‘all units’ to be put on the alert; and for preparations to be made ‘for blacking out cities and other targets’.

By thirty minutes after midnight, in the earliest hour of June 22, Zhukov informed Stalin that this directive had been transmitted to all the frontier districts. Even as its transmission had begun, Hitler, in an after dinner conversation with Albert Speer and Admiral Raeder, spoke of his plans for the creation of a German naval base on the Norwegian coast near Trondheim. It was to be Germany’s largest dockyard. Alongside it would be built a city for a quarter of a million Germans. The city would be incorporated into Greater Germany. Hitler then put on a gramophone record, and played his two guests a few bars from Liszt’s Les Préludes. ‘You’ll hear that often in the near future,’ he said, ‘because it is going to be our victory fanfare for the Russian campaign.’ His plans for the monumental buildings of Berlin, Linz and other cities, Hitler told them, were now to be sealed ‘in blood’, by a new war. Russia would be the source even of architectural advantage. ‘We’ll be getting our granite and marble from there,’ he explained, ‘in any quantities we want.’

Shortly after midnight, in that first hour of June 22, as the warning directive was on its way from Moscow to the frontier forces, the Berlin—Moscow Express crossed the railway bridge over the River Bug and steamed into the Soviet border city of Brest-Litovsk. A little later, two trains, coming from Kobryn, crossed the River Bug in the other direction. One was the regular Moscow—Berlin Express. The other, which followed immediately behind it, was a freight train carrying Soviet grain to the storehouses of Germany.

Life was proceeding as usual. From a point on the frontier further south, a German corps commander informed his superiors that the Soviet town opposite him was visibly unperturbed. ‘Sokal is not blacked out,’ he reported. ‘The Russians are manning their posts which are fully illuminated. Apparently they suspect nothing.’ At Novgorod-Volynsk the Soviet General, Konstantin Rokossovsky was the guest of honour at a concert at his headquarters. Receiving the Moscow Directive, he ordered his commanders to go to their units only ‘after the concert’. In the Officers’ House in Kiev, General Pavlov, commander of the Western Military District, was watching a Ukrainian comedy. Informed that ‘things on the frontier were looking alarming’, he chose to see the end of the play.

Not a concert, or a play, but a ball, was in full swing that Saturday night at the Soviet border town of Siemiatycze, attended, as had become usual for some weeks past, by the German border patrol from the other side, and by many Jews. At four o’clock in the morning, the ball was still in progress. Minute succeeded minute in raucous song and swirling dance. ‘Suddenly’, the historian of Siemiatycze has recorded, ‘bombs began to fall. The electricity in the hall was cut off. Panic-stricken and stumbling over each other in the darkness, everyone ran home.’

As the German forces stood on the Soviet frontier in the early hours of June 22, ready to invade, 2,500,000 Soviet soldiers in the Western defence districts faced an estimated 3,200,000 Germans. A further 2,200,000 Soviet soldiers were in reserve, defending the cities of Moscow and Leningrad, and the industrial regions of the Donetz basin and the Urals. The numbers, however, were deceptive; only thirty per cent of the Soviet troops had automatic weapons. Only twenty per cent of the Soviet aircraft and nine per cent of their tanks were of the modern types.

***

The master of eight European capitals—Warsaw, Copenhagen, Oslo, The Hague, Brussels, Paris, Belgrade and Athens—ruler of Europe from the Arctic coldness of the North Cape to the warm island beaches of Crete, his armies unbeaten even further south, on the frontier of Egypt, Hitler had now set his sights and his armies on Moscow. But although the day was to come when the tall spires of the Kremlin were to be visible through the binoculars of his front line commanders, Moscow was never to be his, and the march to Moscow, Napoleon’s downfall in 1812, was to lead, through suffering and destruction, to the end of all Hitler’s plans, and, within four years, to the downfall of his Reich.