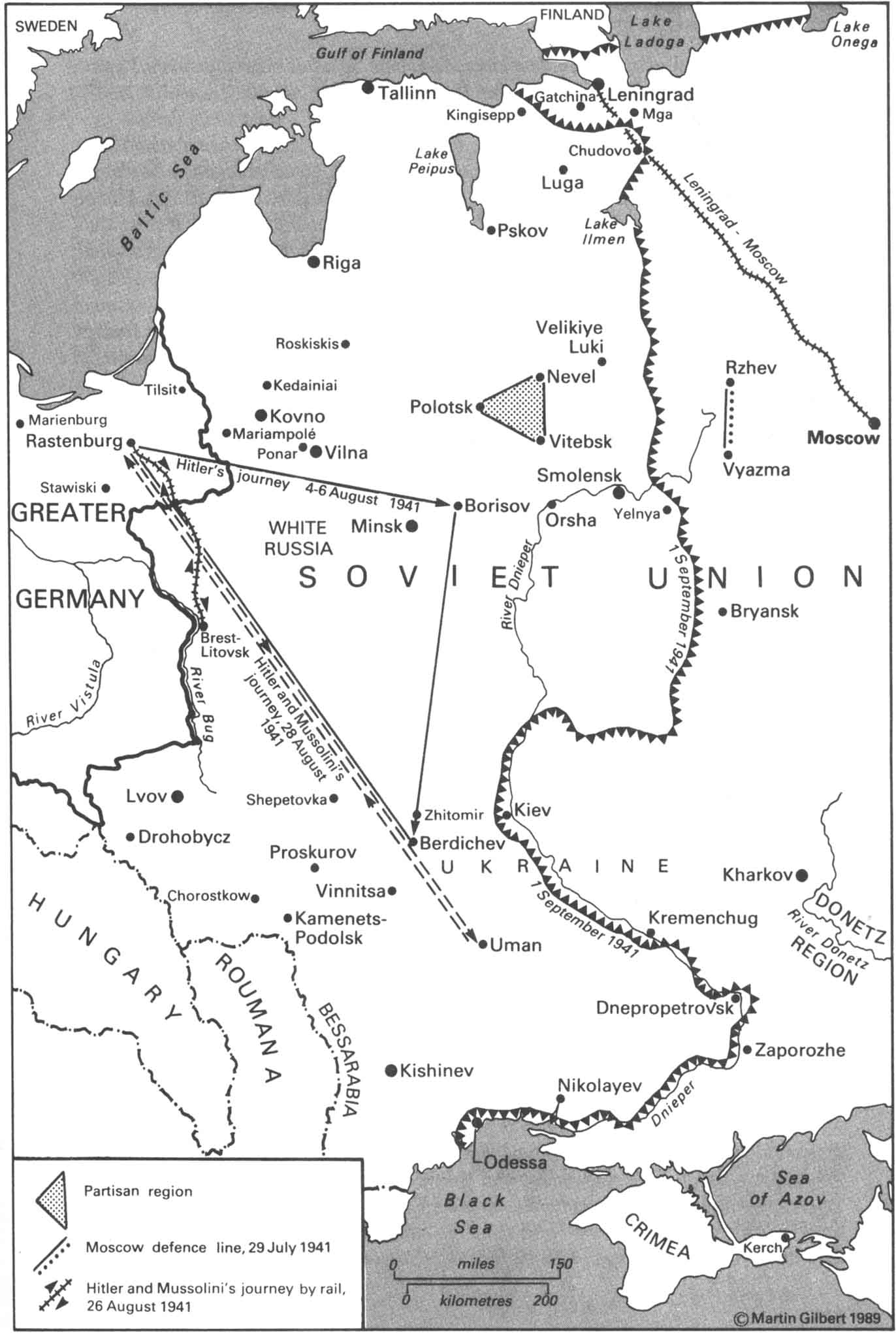

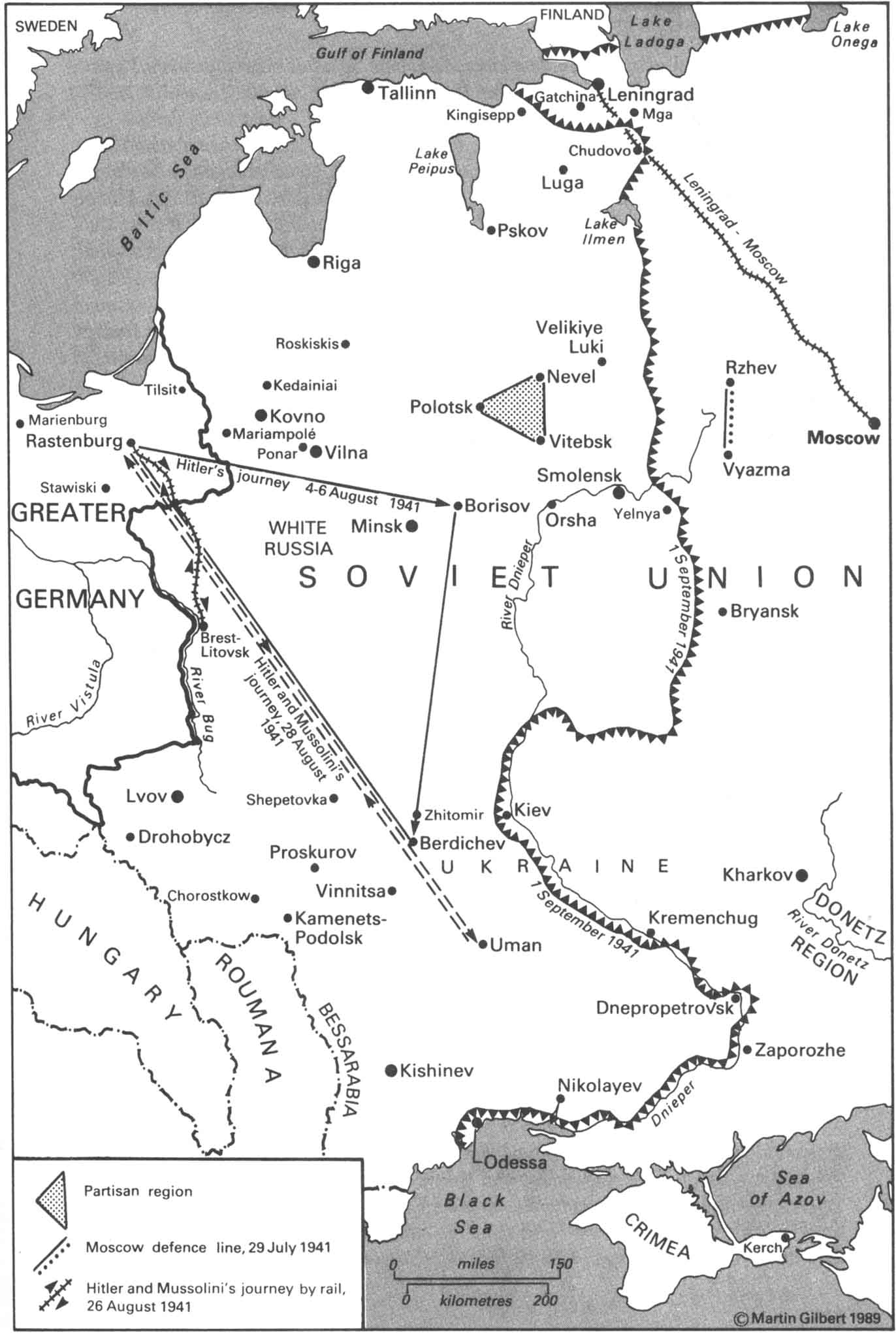

The Eastern Front, August 1941

On 15 July 1941, a German spy, Juan Pujol Garcia, sent his first letter from Britain to his German masters. Garcia was the chief of a network of spies whom he himself had recruited. They included a Dutch airline steward, a censor in the Ministry of Information, a typist in the Cabinet office, an American soldier based in London and a Welsh fascist. All were non-existent, as was Garcia himself: known to the Germans as ‘Arabel’, Garcia was in fact the British double-agent ‘Garbo’, sending a series of totally spurious reports back to Germany, using recruits who were a figment of his imagination.

The success of ‘Garbo’ in deceiving the Germans about British military preparations and intentions was considerable. On the day of his first letter back to Germany, another secret, and in the end far more fateful, communication took place; for on the day of Garcia’s double-cross, a British Government Committee, reporting in the strictest secrecy, concluded that ‘the scheme for a uranium bomb is practicable and likely to lead to decisive results in the war’. It recommended that work on this bomb should continue ‘on the highest priority and on the increasing scale necessary to obtain the weapon in the shortest possible time.’

The urgency of the Anglo-American search for an atomic bomb arose from the Allied belief that the Germans were also working on a similar project, which could lead to the destruction of whole cities in Britain.

In mid-July 1941, however, it was Russia which seemed on the verge of destruction. On July 16, the day after the British ‘uranium bomb’ report, German forces began the encirclement of the Soviet city of Smolensk, halfway between Minsk and Moscow, and at the centre of the second of the defensive lines established a mere three weeks earlier. At his headquarters, Hitler was jubilant. ‘In principle,’ he told an inner circle of confidants, including General Keitel and Alfred Rosenberg, ‘we must now face the task of cutting up our cake according to our needs in order to be able: first, to dominate it; second, to administer it; third to exploit it.’ Never again must there be ‘any military power West of the Urals, even if we have to fight a hundred years’ war to prevent it’. As to criticisms of the killing that was proceeding behind the German lines, here Hitler was equally positive. ‘The Russians’, he said, ‘have now given an order to wage partisan warfare behind our front. This guerrilla activity has some advantage for us; it enables us to exterminate everyone who opposes us.’ That day, a German Army order, issued from Army headquarters, associated the regular Army with the new ruthlessness. ‘The necessary rapid pacification of the country’, the order read, ‘can be attained only if every threat on the part of the hostile civil population is ruthlessly taken care of. All pity and softness are evidence of weakness and constitute a danger.’ Everything must be done to promote ‘the spreading of that measure of terror which alone is suited to deprive the population of the will to resist’.

On July 17, Hitler gave Himmler full authority for ‘police security in the newly occupied territories’. The killing of Jews was now a daily occurrence, reported as a matter of routine by the Special Task Forces, as they moved forward steadily from town to town and village to village. ‘Operational Situation Reports, USSR’, as the killing squad statistical reports were called, were compiled regularly in Berlin and sent to as many as sixty German Government departments and officials. Report No. 26, dated July 18, gave the total number of Jews already ‘liquidated’ inside the former Lithuanian border by a Task Force based on Tilsit as 3,302. At Pskov, eighty Jews had been killed. On July 17, seven hundred Jews had been taken out of Vilna to the nearby holiday resort of Ponar; they had all been shot. On July 18, fifty-three Jews had been shot at Mariampolé.

The killing squads operated against Russians as well as against Jews. Three days after the Mariampolé executions of July 18, a group of forty-five Jews were forced to dig a pit, and were then roped together and thrown into the pit alive. The SS then ordered thirty White Russians to cover the live Jews with earth. The White Russians refused. The SS then opened fire with machine guns on Jews and White Russians alike: all seventy-five were killed.

Behind the lines, the Special Task Forces murdered unarmed and frightened civilians without interruption, but at the front the German Army was finding itself confronted by much stiffer resistance than it had been led to expect. British Intelligence learned from the German Army’s own Enigma messages that this was so; that the Germans were disturbed by the scale of their own casualties, planned to slow down the advance, and could no longer provide adequate air protection either to the Panzer formations at the front or to strategic positions at the rear. On July 17, Churchill specifically requested that this information should be sent to Stalin.

News also reached Britain, through German top secret police messages likewise sent through the Enigma machine, of the mass murder, first reported and read on July 18, of ‘Jews’, ‘Jewish plunderers’, ‘Jewish Bolshevists’ and ‘Russian soldiers’.

Hitler was now as worried as his commanders by the Russian ability to retreat and regroup. ‘The aim of the next operations’, he wrote in his Directive No. 33 on July 19, ‘must be to prevent any further sizeable enemy forces from withdrawing into the depths of Russia, and wiping them out.’ Admiral Canaris, returning from Hitler’s headquarters, was reported by one of his staff as saying on 20 July that the mood at Rastenburg was ‘very jittery, as it is increasingly evident that the Russian campaign is not “going by the book”’. The signs were multiplying, Canaris added, ‘that this war will not bring about the expected internal collapse, so much as the invigoration, of Bolshevism’. That same day, July 20, Stalin ordered that all Red Army units ‘should be purged of unreliable elements’.

The Russian people did not depend on purges to maintain the will to fight, and to survive. On July 20, a day before Hitler visited Northern Army Group headquarters and demanded that Leningrad be ‘finished off speedily’, a second trainload of treasures from the Hermitage was sent to safety, to the Ural city of Sverdlovsk. That day, from the Polotsk—Vitebsk area, less than a month earlier Russia’s first line of defence, now behind the lines, a German infantry division assigned to comb the Polotsk—Vitebsk—Nevel triangle, described the area as a ‘partisan region’, and reported that the roads were being mined every day.

July 20 was also the day on which the first British naval vessel, a minelayer, crossed the North Sea on its way to the Soviet Arctic port of Archangel with military supplies. Three days later, a substantial British naval force of two aircraft carriers, two cruisers and six destroyers left Scapa Flow to carry out attacks, at Stalin’s request, on German ships taking war supplies between the Norwegian port of Kirkenes, and Petsamo, the Finnish-controlled base for operations against the Murmansk region. These British warships were to be the first of a series of naval forces sent to help Russia, or to bring help to Russia, through Arctic waters, beyond the North Cape, in what the Soviet Ambassador to London, Ivan Maisky, was later to call ‘a northern saga of heroism, bravery and endurance’.

On July 21 the Germans launched their first air raid on Moscow; watching the city’s anti-aircraft defences in action, the Western journalist Alexander Werth noted ‘a fantastic piece of fireworks—tracer bullets, and flares, and flaming onions, and all sorts of rockets, white and green and red; and the din was terrific; never saw anything like it in London’. There was a second raid on the following night.

At the Soviet—German border, the garrison of Brest-Litovsk, surrounded and isolated hundreds of miles in the rear, had held out for thirty days against German bombers and artillery. On July 23, after a pounding by a new German mortar, ‘Karl’, which fired a projectile weighing over two tons, the garrison surrendered. The courage of the defenders was cause for pride to those Russians struggling to hold the line so much further east, or to maintain the fight behind the lines. It was indeed the partisan war which caught the Germans by surprise. On July 23, in a supplement to his Directive No. 33, Hitler stressed that the commanders of all areas behind the front were ‘to be held responsible together with the troops at their disposal, for quiet conditions in their areas’. They would ‘contrive to maintain order’, Hitler added, ‘not by requesting reinforcements, but by employing suitably draconian methods’.

How ‘draconian’ these methods could be was clear from an SS report which listed the executions carried out in the Lithuanian town of Kedainiai on July 23 as ‘eighty-three Jews, twelve Jewesses, fourteen Russian Communists, fifteen Lithuanian Communists, one Russian Commissar’.

The Eastern Front, August 1941

***

It was on July 23 that a new British film was shown to the press, two days before its public release. Called Target for Tonight, it centred on a bombing raid over Germany. The impact of the film was immediate. Produced by Harry Watt, and with a real pilot, Squadron Leader Pickard, at the controls, it provided a boost to British morale. The phrase ‘Target for Tonight’ became a national catchword on radio and the stage.

On July 24, British Bomber Command launched Operation Sunrise, against the German battle-cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, and on the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, then at Brest and La Pallice. The raid was a failure; seventeen aircraft were lost, for negligible damage to the ships. That day, in the Far East, following the decision taken in Tokyo on July not to move against Russia but through South-East Asia instead, 125,000 Japanese troops moved into Indo-China. Five days later they had occupied Cam Ranh naval base, only eight hundred miles from the Philippine capital of Manila and from the British base at Singapore. The Vichy authorities had said they would allow in 40,000 Japanese troops. But they had no means of insisting that this bargain was kept. Two days later, on July 26, as a gesture of disapproval and retaliation, Roosevelt seized all Japanese assets in the United States; this was followed by similar action by the British Empire and the Dutch East Indies, cutting off Japan, at a stroke, from three-quarters of her overseas trade and ninety per cent of her oil imports. Japan’s own oil resources could last for three years at the very most. At the same time, the Panama Canal was closed to Japanese shipping, and General Douglas MacArthur took over command of American forces in the Far East, and of the Philippines force, now facing the Japanese in French Indo-China across the South China Sea. As he did so, Japanese forces entered Saigon, once more with the Vichy authorities’ reluctant agreement.

On July 26, in the Mediterranean, Italian motor torpedo boats brought special piloted torpedoes—known to the Italians as ‘pigs’, and to the British as ‘chariots’—into Malta’s Grand Harbour. Before the men on these ‘pigs’ could find their targets, they were seen and attacked; fifteen of them were killed and the rest taken prisoner. Not all deaths that day were in action. On the Russian front, NKVD troops rounded up a thousand deserters from a single regiment; forty-five were shot, seven of them in front of the assembled regiment. That same day, in Lvov, Ukrainians began a three day orgy of killing against the Jews of the city; at least two thousand Jews were murdered in those three days.

Elsewhere in the conquered areas of Russia, the German plans for the Jews were changing. After the initial slaughter of thousands, ghettos were being set up in which those who had survived the massacres were to be confined. On July 27 the new Reich Commissar for the Baltic States and White Russia, Hinrich Lohse, was told that the inmates of the ghettos under his authority were to receive ‘only the amount of food that the rest of the population could spare, and in no case more than was sufficient to sustain life’. These minimal food rations were to continue ‘until such time as the more intensive measures for the “Final Solution” can be put into effect’.

In Vilna, even after the ghetto had been established, the killings continued, at the nearby resort of Ponar, the very name of which had already joined that dreaded vocabulary of places associated with brutality and killing: Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald, Mauthausen and many more, a growing number. On July 27 a Polish journalist, W. Sakowicz, who lived at Ponar, and was himself to be killed during the last days of German rule in Vilna, wrote in his diary: ‘Shooting is carried on nearly every day. Will it go on for ever? The executioners have begun selling the clothes of the killed. Other garments are crammed into sacks in a barn at the highway, and taken to town.’ Between two and three hundred people, Sakowicz added, ‘are being driven up here nearly every day. And nobody ever returns….’

In Belgrade, after four bomb attacks on German military vehicles, the Germans acted swiftly to prevent further acts of resistance. No one had been killed in the four attacks. But on July 27 the Germans rounded up 1,200 Jews, brought them to a camp just outside the city, divided them into their professions, and declared every tenth person a ‘hostage’. The 120 hostages were then taken away and shot.

***

It was only on July 27 that the Germans completed their encirclement of Smolensk, cutting the Russian lines of communication to Vyazma, and taking more than 100,000 Russian prisoners. That day, a Soviet order sentencing nine Soviet senior officers to death was read out to all officers and men. Those sentenced included Generals Pavlov, Klimovskikh and Korobkov. Also shot, but in secret, was General Pyadyshev, who had organized the Luga defence line for Leningrad.

On July 27, German bombers returned to Moscow for the fifth consecutive night. ‘The Kremlin is a heap of smouldering ruins,’ Goebbels declared. In fact, a single bomb had fallen just outside the Kremlin, making a deep crater.

On July 28 the Red Army was forced to abandon Kingisepp, less than seventy miles from Leningrad. To build defence works, 30,000 Leningrad citizens were taken with spades, picks and shovels under the slogan ‘At Kingisepp—to the trenches’. Nearly 100,000 were sent to the area around Gatchina, known since the Revolution as Krasnogvardeisk. At the same time, plans were made to meet the German occupation with partisan activity; on July 28, the Soviet authorities in Vyazma issued ‘Assignment No. 1’, the creation of a partisan unit of 350 men who would deliberately be left behind when the Red Army retreated. Its task would be to destroy German food, fuel and supply dumps, to destroy the Smolensk—Vyazma and Vyazma—Bryansk railway lines, and to derail trains; to prevent the use of Vyazma airport by the Germans by destroying planes and fuel; to kill ‘higher and lower level German war staffs’, to capture ‘high German officers’; to hand over to the Red Army any documents containing ‘valuable information about the enemy’; and to set up two or three ‘diversionist groups’ to perform ‘special tasks’.

On July 28, the day on which this Vyazma plan was laid down, and the would-be partisans received their instructions, Himmler issued orders authorizing SS military units that were fighting alongside regular German Army units to take ‘cleansing actions’ against villagers who ‘consisted of racial inferiors’ or who were suspected of helping partisans. In cases of help to partisans, anyone under suspicion was to be executed immediately, and the village then ‘burned to the ground’.

In the town of Drohobycz, two weeks after the first massacre of Jews, SS Sergeant Felix Landau wrote in his diary: ‘In a side turning we notice some Jewish corpses covered with sand. We look at each other in surprise. One living Jew rises up from among the corpses. We despatch him with a few shots. Eight hundred Jews have been herded together; they are to be shot tomorrow.’

The enormity of the crimes, and the vastness of the areas now occupied by Germany, had created unease among a small group of senior German officers, who feared that the grandiose hopes of victory were likely to be dashed by eventual stalemate and even defeat. ‘No one has ever succeeded in defeating and conquering Russia,’ Admiral Canaris had remarked in the presence of Lieutenant Fabian von Schlabrendorff, an officer on the staff of Major-General Henning von Tresckow, and the General’s relative by marriage. It was Tresckow who, at the end of July 1941, while at Army Group Centre, tried to win the support of Field Marshal von Kluge for an attempt to arrest Hitler and depose him. But von Kluge, though Hitler had once dismissed him from his command in 1938, would not be drawn.

***

On July 29 a new Soviet defence line was created, between Rzhev and Vyazma, guarding Moscow. That day, in Moscow, Harry Hopkins spoke to Stalin about the American aid that was on its way: two hundred American fighter planes were being sent by ship to Archangel, and, Hopkins explained, ‘an outstanding expert in the operation of these planes’, Lieutenant Alison, was already in Moscow.

The despatch of aid to Russia by sea was only made feasible because, by the end of July, all German submarine instructions were being read by the British cryptographers at Bletchley ‘continuously and with little or no delay’; that month the number of Allied merchant ships sunk, which had been more than ninety in May, fell to below thirty, because it was now possible to route Atlantic convoys around German submarine concentrations. A month earlier, a secret message system similar to the Enigma, the key to the Italian Navy’s high grade cypher machine, C38m, had also been broken, giving the British details of the sailings of all Italian troop and supply ships from Italy to North Africa.

The setbacks to the Italians were eventually to draw Germany more and more deeply into the Western Desert struggle; but at the end of July 1941 it was Germany’s triumph in the East which was predominant. By July 30, noted a senior German Staff Officer, General von Waldau, the Germans in Russia had taken 799,910 prisoners, and destroyed or captured 12,025 tanks. At the same time, the carrying out the Commissar Decree, and also the killing of Jews, had continued without respite, the killers following the German armies as they advanced more and more deeply into the Ukraine. On July 30, Himmler’s Special Task Forces compiled their fortieth Operation Situation Report USSR. In Zhitomir, 180 ‘Communists and Jews’ had been shot, in Proskurov, 146 Jews; in Vinnitsa, 146; in Berdichev, 148; in Shepetovka, 17; in Chorostkow, 30. The report added: ‘In this last place, 110 Jews were slain by the local population.’ At Ponar, outside Vilna, the Polish journalist Sakowicz wrote in his diary that day: ‘About 150 persons shot. Most of them were elderly people. The executioners complained of being very tired of their “work”, of having aching shoulders from shooting. That is the reason for not finishing the wounded off, so that they are buried half alive.’

***

In his Directive No. 34, issued from Rastenburg on 30 July, Hitler ordered that the Soviet troops fighting north-west of Kiev ‘must be brought to battle west of the Dnieper and annihilated’. In this same directive, however, he urged caution and retrenchment elsewhere, in an attempt to focus his military efforts more effectively. Army Group Centre was ‘to go over to the defensive’. Armoured units were to be withdrawn from the front line ‘for quick rehabilitiation’. On the Finnish front, only such forces were to be left ‘as are necessary for defence and to give the impression of further offensive operations’.

***

On July 31, in the Bessarabian city of Kishinev, the first ‘five-figure’ civilian massacre of the war came to its end; after fourteen days of uninterrupted slaughter, ten thousand Jews had been murdered. That same day, from Berlin, Field Marshal Goering sent Reinhard Heydrich a letter, ‘on the Führer’s instructions’, ordering him to ‘make all necessary preparations as regards organization and actual concrete preparations for a general solution of the Jewish problem within German sphere of influence in Europe’.

Behind this verbose and convoluted sentence lay a blueprint for mass annihilation.

‘Hitler’s greatest weakness’, Stalin told Harry Hopkins on July 31, at their second meeting in the Kremlin, ‘was found in the vast numbers of oppressed peoples who hated Hitler and the immoral ways of his Government.’ These people, Stalin added, ‘and countless other millions in nations still unconquered, could receive the kind of encouragement and moral strength they needed to resist Hitler only from one source, and that was the United States’.

***

In Auschwitz concentration camp, at the end of July, a Pole escaped from a labour detail. As a reprisal, ten men in his block of six hundred were chosen at random, to be locked in a cell and starved to death. After the selection, a Polish Catholic priest, Father Maximilian Kolbe, who was also a prisoner, approached the camp Commandant and asked to take the place of one of those who had been selected. ‘I am alone in the world,’ Kolbe said. ‘That man, Francis Gajowniczek, has a family to live for.’ ‘Accepted’, said the Commandant, and turned away. Father Kolbe was the last to die. Thirty years later, at a ceremony of beatification for Kolbe, the man whose place he took, Francis Gajowniczek, attended, together with Gajowniczek’s wife.

In the week of Father Kolbe’s act of courage, a German Army officer, Major Rosler, was alerted in his barracks at Zhitomir by a ‘wild fusillade’ of rifle fire. Looking for its source, he climbed an embankment, from which he looked down upon ‘a picture of such barbaric horror that the effect upon anyone coming upon it unawares was both shattering and repellant’. Major Rosler was looking down into a pit filled with the bodies of dead and dying Jews. At the edge of the pit were German soldiers, some in bathing shorts because it was such a hot day. Local civilians were watching the scene with curiosity; a number had brought their wives and children to watch the spectacle. In the pit, Rosler recalled, ‘lay, among others, an old man with a white beard clutching a cane in his left hand. Since this man, judging by his sporadic breathing, showed signs of life, I ordered one of the policemen to kill him. He smilingly replied: “I have already shot him seven times in the stomach. He can die on his own now.”’

Five months after witnessing this scene, Rosler protested about it to his superiors. ‘I cannot begin to conceive’, he wrote, ‘the legal decisions on whose basis these executions were carried out. Everything that is happening here seems to be absolutely incompatible with our views on education and morality.’

On August 1, in Minsk, Himmler himself witnessed an execution. He had the ‘bad luck’ on that occasion, his senior liaison officer, SS General Karl Wolff later recalled, ‘that from one or other of the people who had been shot in the head, he got a splash of brains on his coat, and I think it also splashed into his face, and he went very green and pale; he wasn’t actually sick but he was heaving and turned round and swayed and then I had to jump forward and hold him steady and then I led him away from the grave’.

Following this episode, Himmler told those doing the shooting that they must be ‘hard and firm’. But he also asked the head of the German Criminal Police, Arthur Nebe, who held the rank of general in the SS, and who, since June 22, had been in charge of Special Task Force B, operating in White Russia, to find some new method of mass killing. After the war, an amateur film was found in Nebe’s former Berlin apartment, showing a gas chamber worked by the exhaust gas of a lorry.

A new policy on mass killing was about to emerge. At Auschwitz that August, the deputy camp Commandant, SS Captain Karl Fritsch, conducted experiments in killing by gas, using a commercial pesticide, prussic acid, marketed under the German trade name of ‘Zyklon-B’. The victims on whom he chose to experiment were Russian prisoners-of-war.

In its frequently used commercial form, Zyklon B had a special irritant added, so that those who used it against insects would be warned by its noxious smell to stay well clear of it. Now the irritant was removed, so as not to create alarm or panic among those against whom it was being used; and a special label on each tin warned those who operated the gas chambers that these particular tins were ‘without irritant’.

***

On August 2, the Red Army, which had been in almost continuous retreat for fifty days, began a twenty-eight-day tank battle to drive the Germans back from the Yelnya salient; although, in October, the Russians in Yelnya were to be encircled and destroyed, their success in August, the first victory of the Red Army over the Germans, was a powerful boost to Russian morale. Visiting Army Group Centre at Borisov on August 4, Hitler told two of his senior commanders, Field Marshal von Bock and General Guderian: ‘Had I known they had as many tanks as that, I’d have thought twice before invading.’

On August 6, Hitler flew from Borisov to Berdichev, to visit the headquarters of Army Group South. With him was Walther Hewel, who noted in his diary: ‘Ruined monastery church. Opened coffins, execution, ghastly town. Many Jews, ancient cottages, fertile soil. Very hot.’ Hitler flew back to his headquarters at Rastenburg. On the following day, the German police commander in the central sector, von dem Bach Zelewski, reported to SS headquarters in Berlin that his units had carried out 30,000 executions since their arrival in Russia. The SS Cavalry Brigade also sent in a report to Berlin that day, to say that it had carried out 7,819 ‘executions’ to date in the Minsk area. To ensure maximum secrecy, both reports were sent by the most secure radio cypher system available, the Enigma. As a result, both were read by British Intelligence. Hitler too must have read these reports; five days earlier the Gestapo chief, Heinrich Müller, had written from Berlin to the commanders of the four Special Task Forces, including SS General Nebe of Task Force B, that ‘the Führer is to be kept informed continually from here about the work of the Special Task Forces in the East’.

The work of these task forces was continuous and comprehensive. Operational Situation Report No. 43, compiled in Berlin on August 5, spoke of measures in twenty-nine towns ‘and other small places’ in which the units had ‘rendered harmless’ people in the following categories: ‘Bolshevik Party officials, NKVD agents, active Jewish intelligentsia, criminals, looters, partisans etc.’. The partisans could not, however, be so easily rooted out. From Vitebsk, on August 8, the local German authorities reported that the Soviet partisans in the region operated in such small groups, or even as individuals, that they ‘could not be eliminated’ by regular military or police operations.