The Siege of Leningrad, October 1941–January 1944

On 8 August 1941, as Russian troops and civilians fled from the Black Sea port of Odessa, orders arrived from Moscow: ‘The situation on the land front notwithstanding, Odessa is not to be surrendered.’ Three days later, as Churchill and Roosevelt met, for the first time as leaders, off Newfoundland, the Soviet Air Force carried out its first air raid on Berlin. Hitler now suspended the attack on Moscow and ‘concluded’ the operation against Leningrad.

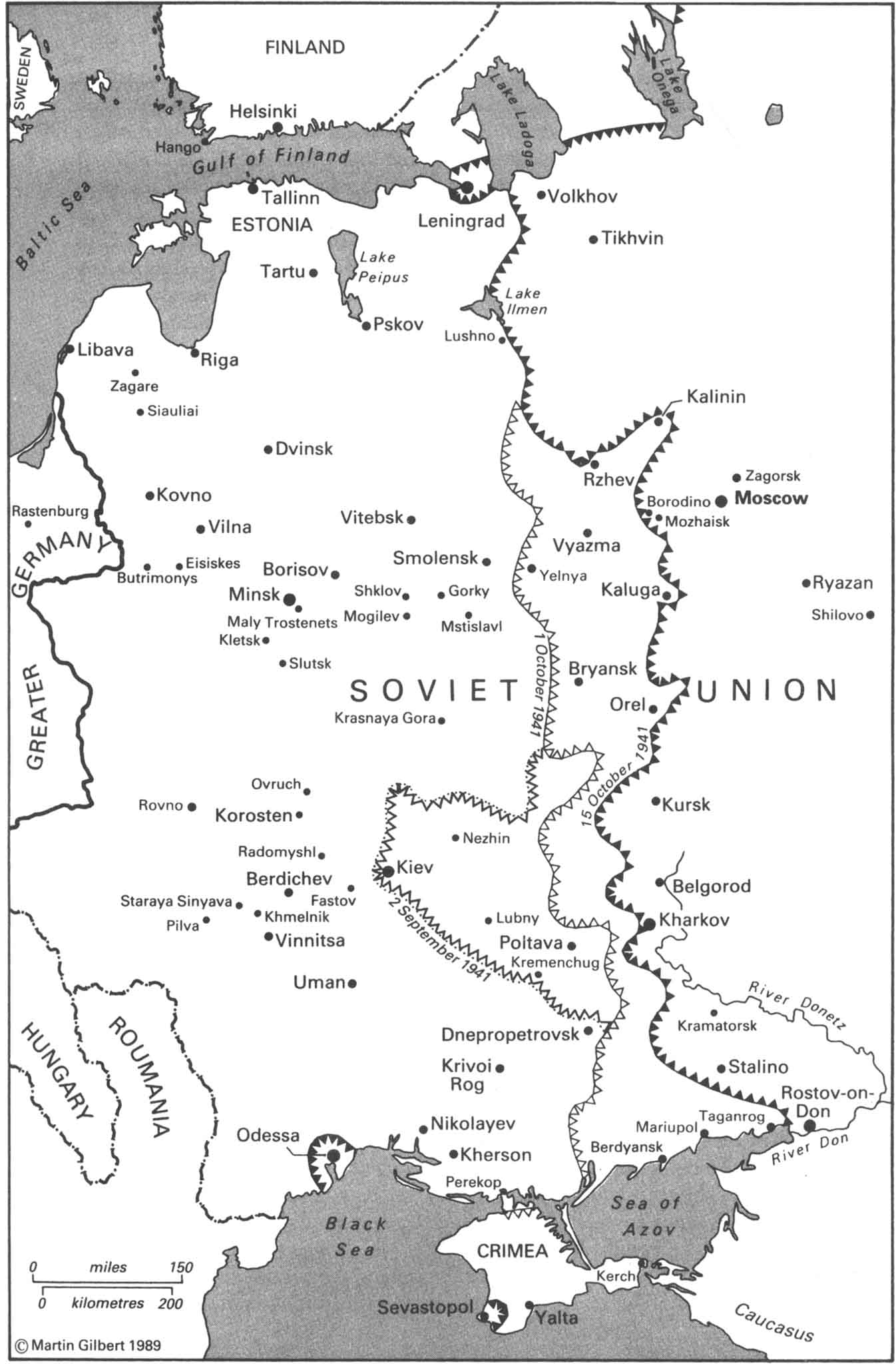

On August 12, in a supplement to his Directive No. 34, Hitler set as the immediate German objectives the occupation of the Crimea, of the industrial region of Kharkov and of the coalfields of the Donetz basin. Once the Crimea was occupied, an attack across the Kerch Straits, in the direction of Batum, ‘will be considered’. It was ‘urgently necessary’, Hitler added, ‘that enemy airfields from which attacks on Berlin are evidently being made should be destroyed’.

On board ship, at Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, Churchill and Roosevelt agreed, after hearing Hopkins’s account of his meetings with Stalin, to give immediate aid to Russia ‘on a gigantic scale’. Churchill also drafted a statement, which Roosevelt agreed to issue under his own name, that any ‘further encroachment’ by Japan in the south-west Pacific ‘would produce a situation in which the United States Government would be compelled to take counter-measures, even though these might lead to war between the United States and Japan’.

During their discussions, Churchill and Roosevelt agreed to issue a public document, the Atlantic Charter, setting out a joint Anglo-American commitment to a post-war world in which there would be ‘no aggrandizement, territorial or other’, as a result of the war, and no territorial changes ‘that do not accord with the freely expressed wishes of the people concerned’. In a section directed at those who were under German, Italian or Japanese occupation, the Atlantic Charter pledged that Britain and the United States ‘wish to see sovereign rights and self-government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them’.

These words of encouragement were made public on August 12. On the following day, in Paris, fighting broke out between demonstrators and the French and German police. Seven days later, two of the demonstrators were executed: Henry Gaultherot and Szmul Tyszelman. Both were Communists. Tyszelman was also a Jew.

***

In order to give aid to Russia, Churchill and Roosevelt had authorized, while on board ship in Placentia Bay, the immediate despatch of an Anglo-American Military Mission to Moscow, to discuss Soviet needs in relation to American production. Arthur Purvis, who had done so much in the United States to acquire war supplies for Britain a year earlier, was to be a leading member of the Mission. He was killed, however, when the aeroplane bringing him to Placentia Bay from Britain crashed on take off.

In spite of the death of Purvis, the importance of the Mission was underlined by the senior status of its two chiefs, Lord Beaverbrook for Britain and Averell Harriman for the United States. Both were masters of the questions of production and supply; it was Beaverbrook who, in the summer of 1940, as Minister of Aircraft Production, had ensured that the maximum possible number of fighter planes had been manufactured in the quickest possible time. For as long as the Russian front ‘remained in being’, Churchill explained to his War Cabinet on his return to London, ‘we might have to make some sacrifices’ as far as British supplies from the United States were concerned. He had ‘thought it right’, he said, to give Roosevelt a warning ‘that he would not answer for the consequences if Russia was compelled to sue for peace and, say, by the spring of next year, hope died in Britain that the United States were coming into the war’.

On August 12, while Churchill was still with Roosevelt off Newfoundland, two squadrons of British fighters, forty aircraft in all, commanded by a New Zealander, Wing Commander Ramsbottom-Isherwood, left Britain on HMS Argus for Murmansk and Archangel. Even before the British fighters reached Murmansk, two British submarines, Tigris and Trident, had managed to make their way to the Soviet naval base at Polyarnoe, near Murmansk. There, they at once began operations against German troop transports and coastal shipping off the northern Norwegian and Finnish coastlines.

***

In the conquered regions of Russia, the terrorising of the population continued. On August 13, as Dr Moses Brauns, a Jewish doctor in Kovno, later recalled, three hungry Jews bought a few pounds of potatoes from a Lithuanian peasant on a street just outside the ghetto. The Germans punished this desperate purchase by rounding up twenty-eight Jews at random, and shooting them. On the following day, August 15, at Roskiskis, near the former Lithuanian—Latvian border, a two-day orgy of killing began, in which 3,200 Jews were shot, together, as the Special Task Force reported, with ‘five Lithuanian Communists, 1 Pole, 1 partisan’. In Stawiski, near the former German—Soviet border, six hundred Jews were shot that day. Also on August 15, in Minsk, Hinrich Lohse issued a decree for the whole of German-occupied Russia, ordering every Jew to wear two yellow badges—one on the chest, one on the back—not to walk on the pavements, not to use public transport, not to visit parks, playgrounds, theatres, cinemas, libraries or museums; and to receive in the ghetto only food which was ‘surplus’ to local needs. All able-bodied Jews were to join labour gangs and to work at tasks laid down by the occupation authorities, such as road-building, bridge-building and repairing bomb damage.

On the day of Lohse’s decree, casting the Jews of German-occupied Russia into a net of restrictions and isolation, Richard Sorge was able to send a radio message from Tokyo to Moscow, reporting that the Japanese Government had confirmed its unwillingness to enter the war against Russia. A war against Russia ‘before the winter season’, so it had been decided, ‘would exert an excessive strain on the Japanese economy’. It was a welcome confirmation; that day, more than a hundred German bombers struck at Chudovo railway station, on the Leningrad—Moscow railway line.

***

On August 18 the Russians evacuated the Black Sea port of Nikolayev. At Hitler’s headquarters, von Brauchitsch proposed a resumption of the attack on Moscow. He was overruled. The main German thrust, Hitler insisted, must be to the Crimea, the southern Russian industrial areas, and the Caucasus. In the north, the pressure on Leningrad must be intensified. Moscow could wait. But, Hitler told Goebbels that same day, he hoped to be ‘beyond’ Moscow by the time winter set in.

Goebbels had come to Rastenburg to raise two specific matters. The first was the growing protest inside Germany against the euthanasia programme. On August 3, in Münster, the Bishop, Count Clemens von Galen, had denounced the euthanasia killings from his pulpit. Public unease inside Germany was growing. Bowing to this unease, Hitler ordered the euthanasia programme to be brought to an end: the order was issued to Dr Brack on August 24.

It was indeed a ‘job’ of Himmler’s that was the second matter raised by Goebbels on August 18. When the German soldier came back to Germany after the war, he urged, ‘he must not find any Jews here waiting for him’. There were 76,000 Jews in Berlin. Hitler agreed, as Goebbels noted in his diary, ‘that as soon as the first transport possibilities arise, the Berlin Jews will be deported from Berlin to the East. There they will be taken in hand under a somewhat harsher climate.’

Hitler now reminisced about his ‘prophecy’ of January 1939, that if the Jews ‘once more succeeded in provoking a world war’, it would end with the destruction of Jewry. Hitler was convinced, Goebbels noted in his diary, that his prophecy ‘is coming true’. Goebbels added: ‘It is coming true these weeks and months with a dread certainty that is almost uncanny. In the East, the Jews will have to square accounts….’

On the day of this discussion at Rastenburg, some of these ‘accounts’ were indeed being ‘squared’. In Kovno, a mere 120 miles from Rastenburg, a Lithuanian working for the German authorities in the city, had ordered 534 Jewish writers, intellectuals, professors, teachers and students to report at the ghetto gate for ‘work in the city archives’. Many volunteered for what appeared to be a not too onerous task, perhaps even an interesting one. Among the volunteers was Robert Stenda, who before the war had been leader of the orchestra at the Kovno Opera House. ‘They saw the promise of money and better food’, one young Kovno Jew, Stenda’s friend Joseph Kagan, later recalled, ‘and perhaps better conditions for their families’. The Jews set off. ‘The relatives waited that evening for their return,’ Kagan wrote. ‘They waited through the next day, and the next. The pick of the ghetto’s young men did not return.’ All had been taken on the day of the selection to one of the old forts that surrounded the city, and shot.

East of Kovno, the battles continued; that August 18, a young German Army officer, Lieutenant Kurt Waldheim, who had seen continuous action at the front for almost two weeks, was among those who received the Cavalry Assault Badge, in recognition of his valour. ‘For the good of the German people,’ Hitler told his visitors at Rastenburg on August 19, ‘we must wish for a war every fifteen or twenty years. An army whose sole purpose is to preserve peace leads only to playing at soldiers—look at Sweden and Switzerland.’

Determined to plan the style of his victory, on August 20 Hitler instructed Albert Speer that, in the monumental centre of the new Berlin, thirty captured Soviet heavy artillery pieces would be placed between the remodelled south station and the yet to be erected triumphal arch. Any ‘extra large’ Soviet tanks that were captured would be reserved for setting up in front of the important public buildings. Both the artillery pieces and the tanks would be placed on granite pedestals.

That night, the first German armoured units reached Gatchina, only twenty-five miles from Leningrad. On the following day they captured Chudovo, cutting the railway line between Leningrad and Moscow. Even as the siege of Leningrad began, the Australian troops besieged in Tobruk for the past four months, having lost 832 men killed, sailed away from the city and back to Egypt, to be replaced by British troops. After the soldiers’ sufferings in Greece and Crete, their commanders, and the politicians on the other side of the globe, were insistent that they should be pulled out; around Tobruk, 7,000 had been taken prisoner.

On August 20, Italian troops on the Dalmatian coast of Yugoslavia occupied the town of Gospic and the island of Pag. In both places they found evidence of the mass murder of Serbs and Jews by the local Ustachi fascists. On Pag, 791 corpses were exhumed, of which 293 were women and 91 were children. In the camp at Jadovno, twelve miles from Gospic, at least 3,500 Jews and Serbs had been murdered since mid-July, some beaten to death while at forced labour, and others shot.

In the early hours of August 21, in the former Yugoslav city of Sabac, Jews and Serbs were massacred in the streets as a reprisal against an attack on a German patrol. Other Jews were then rounded up and ordered to hang the corpses from lamp-posts. ‘How can one hang a dead person,’ Mara Jovanovic asked, recalling that terrible morning, ‘and who will summon the courage to do it? A noose was put around one victim’s neck, while the rest of the rope lay in the blood. People hurry by, their heads bent….’ On the next day the Jews were ordered to cut the bodies down, and take them away in rubbish trucks. ‘There was not a soul who did not mourn’, Mara Jovanovic recalled, ‘not only for the dead in the lorries but also for the living behind the lorries.’

Also on August 21, in Paris, a twenty-two year old Communist, Pierre Georges, who was later to adopt the code name ‘Fabien’, shot and killed a young German officer-cadet in a Métro station. It was the first violent act against a German in Paris since the occupation more than a year earlier. More than a hundred and fifty Frenchmen were rounded up and shot as a reprisal.

That August, British Signals Intelligence had several successes, including glimpses of German rule in the East. One particular success in the global sphere was to intercept the text of a radio message from the Japanese Ambassador in Berlin, reporting on a conversation with Hitler, in which Hitler had assured him that ‘in the event of a collision between Japan and the United States, Germany would at once open hostilities with the United States’. A decrypt of this telegram was immediately sent to Roosevelt. Another Intelligence success was the intercepting of German police messages sent from the East by Enigma on seventeen separate occasions, beginning on August 23 and continuing for eight days, setting out details of the shooting of Jews in groups numbering from 61 to 4,200; ‘whole districts are being exterminated’, Churchill revealed, in a broadcast to the British people on August 25. ‘Scores of thousands, literally scores of thousands, of executions in cold blood are being perpetrated by the German police-troops upon the Russian patriots who defend their native soil. Since the Mongol invasions of Europe in the sixteenth century, there has never been methodical, merciless butchery on such a scale, or approaching such a scale’.

Churchill could make no specific reference to the Jews; had he done so, it would have indicated to the Germans that British Intelligence was receiving their most secret messages. But he did make it clear that the Germans were carrying out what he called ‘the most frightful cruelties’, telling his listeners: ‘We are in the presence of a crime without a name.’

***

On August 25, British and Indian forces launched Operation Countenance, the occupation of the southern oilfield region of Iran, while Soviet troops entered Iran from the north. That same day, the British and Soviet ambassadors in Teheran, acting in unison, presented an ultimatum to the Iranian Government, requiring them to accept the ‘protection’ of the two Allies. Three days later, after protesting against this Anglo-Soviet ‘aggression’, the Shah, Reza Pahlavi, abdicated in favour of his son. In another Anglo-Soviet enterprise on August 25, Operation Gauntlet, British, Canadian and Norwegian commando units landed on the Norwegian island of Spitzbergen, in the Arctic Ocean. There, they destroyed coal stores, mining machinery and oil reserves, to prevent them being used by the Germans, and evacuated two thousand Russian civilians, who were then taken southward to Archangel on board the Empress of Canada. Also evacuated from Spitzbergen were fifty French officers who, having been captured by the Germans in France in May 1940 and taken to a prisoner-of-war camp in East Prussia, had then escaped to Russia, hoping to join the Free French forces. Instead, the Russians had interned them on Spitzbergen. Now they were free to fight again.

***

On August 26 the German forces in the Ukraine captured the industrial city of Dnepropetrovsk. Much of its industry, however, had earlier been evacuated to the Urals, leaving only empty buildings. That same day, Hitler was host to Mussolini, showing him the battlefield of Brest-Litovsk, the citadel of which had been reduced to rubble by his mortar ‘Fritz’. That day, near Velikiye Luki, the Russians launched a counter-attack, but were halted within twenty-four hours.

In Moscow, on August 27, the Russians published the casualty figures for the twenty-four German air raids on the capital since the German bombing had started on July 27; in all, 750 Muscovites had been killed. That night, in Leningrad, the poetess Vera Inber recalled over the radio the words of Alexander Herzen, the nineteenth-century writer, that ‘tales of the burning of Moscow, of the Battle of Borodino, of the Berezina Battle, of the fall of Paris, were the fairy stories of my childhood, my Iliad and my Odyssey’. In these present days, Vera Inber told her listeners, Russia was creating for future generations new Odysseys, new Iliads. That night, the Russians began the evacuation of 23,000 soldiers and civilians by sea from the Baltic port of Tallinn. In this Baltic ‘Dunkirk’, Admiral Tributs commanded an evacuation fleet of 190 ships which had to traverse 150 miles of water between two coasts occupied by the Germans. Of his twenty-nine large troop transports, twenty-five were sunk, and more than five thousand soldiers and civilians drowned. The heroism of the sailors entered into legend; of the thirty-five crew members on one troop transport, the Kazakhstan, only seven survived; each one was awarded the Order of the Red Banner. Their commanding officer, however, Captain Vyacheslav Kaliteyev, who was said to have left his ship at a crucial moment, without reason, was later accused of desertion under fire and cowardice. He was executed by firing squad.

As the Tallinn evacuation continued throughout August 28, in the Ukraine, the Russians destroyed the Zaporozhe dam on the Dnieper river to prevent its hydro-electric power being used by the Germans. That day, Hitler and Mussolini flew over that part of the Ukraine which was already conquered, to Field Marshal von Rundstedt’s headquarters at Uman. Two hundred miles west of Uman, twenty-three thousand Jews were being murdered at Kamenets Podolsk. They had been deported from Hungary by the Hungarian Government. The German civil authorities in the region had demanded that the Jews be taken back, as they ‘could not cope’ with them. The Hungarian Government had refused. It was then that an SS General, Franz Jaeckeln, had assured the German civil administration that he would ‘complete the liquidation of those Jews by September 1’. Marched to a series of bomb craters outside the city, and ordered to undress, the Jews were then mown down by machine gun fire. Many of them, gravely wounded, died under the weight of the bodies that fell on top of them, or were ‘finished off’ with pistol shots. By August 29, the task was done, two days in advance of Jaeckeln’s promised date. Operational Situation Report No. 80 gave the precise figures of those shot as 23,600 ‘in three days’.

The death toll in the East was on an unprecedented scale; ten thousand Soviet evacuees had been drowned off Tallinn, and twenty-three thousand Hungarian Jews murdered at Kamenets Podolsk, in the same three day period. But these were far from the only deaths in those few August days. During those same three days, several thousand German soldiers, and several thousand Russian soldiers, had been killed in action on the battlefield. A list of all those killed may never be compiled. Yet in their meticulous records the Germans ensured that a clear pattern of the killing would at least be transmitted to the authorities in Berlin, to be filed. At Kedainiai, in Lithuania, the Special Task Force assigned to Lithuania noted its particular killing statistics on August 28 as ‘710 Jewish men, 767 Jewish women, 599 Jewish children’: a further 2,076 victims of an unequal war which was being fought far behind the battlefield. Nor had the cancellation of the euthanasia programme brought any end to the killing by gas; on August 28 Dr Horst Schumann, the director of the euthanasia centre at Grafeneck, near Stuttgart, visited Auschwitz, where he participated in the selection of 575 prisoners, most of them Soviet prisoners-of-war, who were then sent to the medical experimental centre at Sonnenstein, near Dresden. None of them survived.

On the day of Dr Schumann’s visit to Auschwitz, Pastor Bernard Lichtenburg, Provost of St Hedwig’s Roman Catholic Cathedral in Berlin, unaware that the openly approved euthanasia programme was being stopped that very day, wrote a letter of protest to the Chief Physician of the Reich, Dr Leonardo Conti. ‘I, as a human being, a Christian, a priest and a German,’ wrote Lichtenburg, ‘demand of you, the Chief Physician of the Reich, that you answer for the crimes that have been perpetrated at your bidding and with your consent, and which will call forth the vengeance of the Lord on the heads of the German people.’ Lichtenburg was arrested, and sentenced to two years in prison. He died while being transferred, still a prisoner, to Dachau concentration camp. In the course of the euthanasia ‘action’, carried out under the code name ‘T4’, more than 80,000 mental patients and 10,000 concentration-camp prisoners had been gassed between September 1939 and August 1941; an average of nearly four thousand a month, or more than a hundred a day.

***

On August 29, Finnish forces, advancing towards Leningrad from the north, recaptured Terioki, which they had been forced to cede to the Soviet Union at the beginning of 1940. On reaching Terioki, however, they advanced no further. Despite German pressure, the Finnish Government had decided not to advance in the Leningrad region beyond the pre-1939 frontier. East of Leningrad, however, Finnish units were advancing towards the shore of Lake Onega, threatening to cut Russian communications between the Baltic and the White Sea. On the following day, August 30, German forces occupied the village of Mga, cutting off the last and most easterly railway link between Leningrad and the rest of Russia. But they were driven out of the village on the following day.

The Russians used every possible armament with which to defend Leningrad. On 30 August the naval guns of the Neva squadron had gone into action against the German positions at Gatchina. On the following day, more than 340 shells were fired. Many naval guns were taken from their ships and mounted on land. Even the gun batteries of the forty-year-old cruiser Aurora, which had fired blanks on the Winter Palace in November 1917, frightening the remnants of the Provisional Government into surrendering to the Bolsheviks, were dismounted, and placed in position on the Pulkovo heights.

In German-occupied Vilna, August 31 saw a German ‘action’ against the Jews of the city. One eye witness, Aba Kovner, saw two soldiers dragging a woman away by the hair. As they did so, a bundle fell from her arms. It was her baby boy. One of the soldiers bent down, ‘took the infant, raised him into the air, grasped him by the leg. The woman crawled on the earth, took hold of his boot and pleaded for mercy. But the soldier took the boy and hit him with his head against the wall, once, twice, smashed him against the wall.’

The Siege of Leningrad, October 1941–January 1944

That night, according to the precise German records of the ‘action’, 2,019 Jewish women, 864 men and 817 children were taken out of the city on trucks to the pits at Ponar, where they were shot. The Operational Situation Report compiled in Berlin called it ‘special treatment’.

On September 1, the Germans recaptured Mga. Leningrad was now entirely cut off by rail from the rest of Russia. Throughout the previous month, a massive factory-evacuation scheme had been put into operation; the equipment of ninety-two factories had been taken out by rail, on a total of 282 trains, the two largest heavy tank works being relocated 1,200 miles to the east, at Chelyabinsk and Sverdlovsk. On September 3, two days after the recapture of Mga, Field Marshal Keitel assured the commander of the forces attacking Leningrad, Field Marshal von Leeb, that Hitler had no objection either to the shelling of the city or to its bombardment from the air.

***

Two years had passed since the German invasion of Poland in 1939. In the East, seventy days had passed since the German invasion of the Soviet Union. The victorious German war machine destroyed whatever it wished to destroy: Polish intellectuals, Soviet prisoners-of-war, Yugoslav partisans, French resistance fighters, each felt the full force of superior power. The Jews, scattered among many nations, were singled out for torture, murder and abuse. In Germany, September 1 marked the day on which all the remaining Jews of Germany, including the 76,000 in Berlin, were ordered to wear a yellow of Star of David on their clothing. Two days later, there was yet another experiment to find the most effective method of mass murder, without the publicly visible horrors and—for the executioners—often demoralizing methods of the pit executions. Six hundred Soviet prisoners-of-war and three hundred Jews were brought to Auschwitz, and gassed with prussic acid. This experiment, like the one which had preceded it, was judged a success.

***

On September 4, the United States destroyer Greer was attacked by a German submarine off Iceland. The submarine had wrongly attributed to the Greer the depth charges which had been dropped against it by a British aircraft. The Greer reached Iceland safely. ‘From now on,’ declared President Roosevelt, ‘if German or Italian vessels of war enter these waters, they do so at their own peril.’ With Roosevelt’s words, an undeclared state of war existed between the United States and Germany in the North Atlantic. Ironically, two days after the attack on the Greer, a United States merchant ship, the Steel Seafarer, on her way to Egypt, was sunk by a German aircraft in the Red Sea, 220 miles south of Suez.

On the Eastern Front, Soviet forces recaptured Yelnya on September 6, their first major counter-attack since the Soviet—German war had begun two and a half months earlier. For the Moscow front, it was a considerable relief. Hitler now abandoned the Crimea—Caucasus strategy which he had laid down so emphatically on August 12, declaring in Directive No. 35, issued from Rastenburg, that conditions were now favourable for a ‘decisive’ operation on the central front. The new assault, on Moscow, was to be given the code name ‘Typhoon’.

On September 8, while Operation Typhoon was still in its planning stage, German forces captured Schlüsselburg, on Lake Ladoga. At the same time, the Finns cut the Leningrad—Murmansk railway at Lodeinoye Polye: Leningrad was besieged. That same day, German bombers dropped more than six thousand incendiary bombs on the city, destroying hundreds of tons of meat, flour, sugar, lard and butter in the four acre Badayev warehouse.

The Eastern Front, September and October 1941

Far to the south-east, on September 8, on the River Volga, the eastward deportation began of all 600,000 ethnic Germans who had lived in the Volga region for two centuries. With the German forces already poised to enter Kiev, Stalin feared possible sabotage and subversion, and took the draconian steps of deporting a whole people. Henceforth, a hundred towns and villages along the Volga, from Marxstadt to Strassburg, were to be empty of their German-speaking inhabitants.

On September 9, the Soviet commander of the South-Western Front, Marshal Budyenny, asked Stalin’s permission to abandon Kiev. Stalin refused. That day, in the North Atlantic, a German submarine ‘wolf pack’ of as many as sixteen U-boats attacked a convoy of sixty-five merchant ships being escorted to Britain by Canadian corvettes from Sydney, Cape Breton. In the ensuing battle, fifteen of the merchantmen were sunk, but not before one of the German attackers, U-501, was forced to the surface by depth charges from two further Canadian corvettes, Chambly and Moosejaw, both of which had been on a training voyage when news of the action reached them. Shortly after this success, Chambly was bombed by German aircraft; she too was sunk.

As the convoy proceeded, it was attacked again, but without loss, one of its attackers, U-207, being sunk.

***

On September 9, British cryptologists at Bletchley decrypted the German orders for Operation Typhoon, the planned attack on Moscow. That same day, Field Marshal von Leeb launched his attack on Leningrad. As the Germans drew closer to the city’s suburbs, the naval guns of the cruiser Maxim Gorky, the battleship October Revolution and the battleship Marat sent a massive barrage of shells on to the German forward positions. An SS division, which had participated in May in the German parachute landing on Crete, was ordered to cross the River Neva north-west of Mga, and to attack Leningrad from the north. Lacking sufficient pontoons, it was unable to do so.

On September 10, as the German forces of Army Group North pressed in upon Leningrad, and those of Army Group Centre put the final touches to their plans for a two-pronged attack towards Moscow, Hitler ordered yet another change of priority: before attacking Moscow, his commanders must complete the encirclement of the Russian forces still holding out, tenaciously, in the central Ukraine. The new order, issued on September 10, was not so easily fulfilled; Russian troops fought tenaciously for two weeks to keep open the trap which was closing around them east of Kiev, between Nezhin and Lubny. By September 16 the trap had closed, and 600,000 Russian soldiers captured. The Germans then renewed their march on Moscow; but the two weeks lost were two weeks which brought nearer the danger which was now being spoken of openly at German headquarters—the encroaching winter. ‘We are heading for a winter campaign. The real trial of this war has begun’, General von Waldau had written in his diary on September 9, one day before the change of plan, but he added: ‘My belief in final victory remains.’

On September 10, the day of his order to switch priority from Moscow to the Ukraine, Hitler took the Hungarian Regent, Admiral Horthy, to the East Prussian town of Marienburg. ‘We don’t have your Jewish problem,’ Hitler told the Hungarian leader. What he did not tell him was the specific fate of the Jews under German rule. On the following day, the Operational Situation Report No. 80 of the Special Task Forces noted that, in the town of Korosten, 238 Jews ‘who were rounded up and driven to a special building by the Ukrainian militia, were shot’. In nearby Fastov, ‘all the Jewish inhabitants’ between the ages of twelve and sixty were shot, ‘making a total of 262 heads’, bringing the ‘total executions’ of that particular Special Task Force during August to ‘7,152 persons’.

‘We don’t have your Jewish problem’: while Hitler was telling Admiral Horthy this, on September 10, one of Hitler’s overseas rulers, Josef Terboven, was proclaiming a state of emergency in Oslo. The mass arrest of trade union leaders began at once. Newspaper editors and journalists were dismissed. That evening Oslo radio announced that the labour unions’ legal adviser, Viggo Hansteen, and the principal shop steward at a railway carriage works, Rolf Wickström, had been sentenced to death by court martial, and already executed. That same day, in the Slovak capital of Bratislava, the Slovak Government, following Germany’s lead, issued a Codex Judaicum, removing the legal rights of Slovakia’s 135,000 Jews.

Also on the night of September 10, German bombers again raided Leningrad. The city’s creamery was hit, destroying tons of butter. The principal shipyard was badly damaged, and eighty fires started. By morning, more than two hundred of Leningrad’s citizens were dead. Not only ordinary bombs, but delayed-action bombs dropped by parachute, had added to the city’s torment.

On September 11, Marshal Budyenny again appealed to Stalin to to be allowed to begin ‘a general withdrawal’ from Kiev. His appeal was also signed by the senior Party official in the city, Nikita Khrushchev. Within hours, Budyenny was dismissed. Telephoning to General Kirponos in Kiev, Stalin told his commanders: ‘Cease, after all, searching for new lines to retreat to, and search for ways to resist, and only resist.’

Stalin and his generals were struggling to find some means of holding on to what remained of western Russia, more than a third of which was now in German hands. In the United States, Major Albert C. Wedemeyer, who had been the American soldier—student at the German Staff College in Berlin from 1936 to 1938, estimated, on September 11, that Germany would have occupied all of Russia west of the ‘general line: White Sea, Moscow, Volga River (all inclusive) by 1 July 1942, and that militarily Russia will be substantially impotent subsequent to that date’.

On September 12, the first snow flurries fell on the Russian front. But no snow settled. That same day, with his Moscow offensive, Operation Typhoon, calling out for the maximum possible armoured reinforcements, Hitler ordered a halt to the advance into Leningrad. Instead, the city was to be starved into submission. Five German tank divisions, two motorized divisions and much of the air support of von Leeb’s army, were to leave the Leningrad front within a week. Von Leeb protested. The thirty Soviet divisions trapped in the city were on the brink of destruction. The German tank crews nearest the city could see the golden spires of the Admiralty building.

Hitler refused to change his decision. East of Kiev, his troops under von Kleist and Guderian had successfully trapped fifty Russian divisions in an enormous pocket. First Kiev, and then Moscow, were the prizes he now sought. This change of plan was passed on to Stalin by his ‘Red Orchestra’ agents in Paris, headed by Leopold Trepper. The Soviet High Command could therefore adjust its defensive plans to meet the reinforced thrusts.

The day on which Hitler ordered the transfer of his armoured forces from the Leningrad to the Moscow front, a briefing was held in his headquarters at Rastenburg which began: ‘High-ranking political figures and leaders are to be eliminated.’ The ‘struggle against Bolshevism’, Field Marshal Keitel explained to his commanders that day, ‘demands ruthless and energetic measures, above all against the Jews, the main carriers of Bolshevism’. That same day, September 12, the British eavesdroppers at Bletchley decrypted a German Police Regiment message that it had ‘disposed’ of 1,255 Jews near Ovruch ‘according to the usage of war’.

***

It was on September 12 that the British Royal Air Force Wing was first in action in Northern Russia. That day from its base at Vianga, seventeen miles north-east of Murmansk, it shot down three German aircraft for the loss of one of its own. For their activities in Russia at so desperate a time, the unit’s commander, Wing Commander H. N. G. Ramsbottom-Isherwood, and three of his airmen, were each awarded the Order of Lenin, the only members of the Allied forces to be honoured in this way.

***

The defence of Leningrad was now being directed by Marshal Zhukov, who, on September 14, ordered a counter-attack on the German positions at Schlüsselburg. When the local commander, General Shcherbakov, replied that ‘it simply could not be done’, he was removed from his command, together with his political commissar, Chukhov. Learning of desertions in the Slutsk—Kolpino section of the siege line, Stalin himself ordered the ‘merciless destruction’ of those who were serving as ‘helpers’ of the Germans. Order No. 0098 informed the defenders of Leningrad of executions carried out as a result of Stalin’s order. Two more outposts of the city were to fall on September 16, the town of Pushkin, and the city’s tramcar terminus at Alexandrovka; but the defence perimeter held. No German troops were to march along the city’s boulevards.

With the imminent halt of the German advance on Leningrad, the city’s airport north of the Neva, to which Zhukov had flown on September 11, remained under Soviet control. Beginning on September 13, and ending two and a half months later, a total of six thousand tons of high-priority freight was flown in: 1,660 tons of arms and munitions and 4,325 tons of food. Hitler’s confidence in victory over Russia was, however, undiminished; on September 15 the German diplomat, Baron Ernst von Weizsäcker, noted in his diary, of his leader’s mood: ‘An autobahn is being planned to the Crimean peninsula. There is speculation as to the probable manner of Stalin’s departure. If he withdraws into Asia, he might even be granted a peace treaty.’ It was at this very time, in mid-September, Albert Speer later recalled, that Hitler ordered ‘considerable increases’ in the purchase of granite from Sweden, Norway and Finland, for the monumental buildings planned for Berlin and Nuremberg.

In Paris, the most westerly capital under Hitler’s rule, September 16 saw the execution of ten hostages, most of them Jews, in a reprisal for attacks by members of the French Resistance on German trucks and buildings. That same day, the German Ambassador to Paris, Otto Abetz, was at Rastenburg, where Hitler told him of his plans for the East. Leningrad would be razed to the ground; it was the ‘poisonous nest’ from which, for so long, Asiatic venom had ‘spewed forth’. The Asiatics and the Bolsheviks must be hounded out of Europe, bringing an end to ‘two hundred and fifty years of Asiatic pestilence’. The Urals would become the new frontier; Russia west of the Urals would be Germany’s ‘India’. The iron-ore fields at Krivoi Rog alone would provide Germany with a million tons of ore a month. From this economically self-sufficient New Order, Hitler assured Abetz, France would have its share; but must first agree to take part in the defeat of Britain.

Inside that New Order, a young German Army officer, Lieutenant Erwin Bingel, was at Uman on September 16. There, as he recalled four years later, he saw SS troops and Ukrainian militiamen murder several hundred Jews. The Jews were taken to a site outside the town, lined up in rows, forced to undress, and mowed down with machine gun fire. ‘Even women carrying children a fortnight to three weeks old, sucking at their breasts’, Bingel recalled, ‘were not spared this horrible ordeal. Nor were mothers spared the sight of their children being gripped by their little legs and put to death with one stroke of the pistol butt or club, thereafter to be thrown on the heap of human bodies in the ditch….’

Two of Lieutenant Bingel’s men suffered a ‘complete nervous breakdown’ as a result of what they saw. Two others were sentenced to a year each in a military prison for having taken ‘snapshots’ of the action. The two Operational Situation Reports that week, No. 86 of September 17 and No. 88 of September 19—No. 87 has never been found—gave the statistics of the unceasing slaughter: these were, in part, 229 Jews killed in Khmelnik, six hundred in Vinnitsa; 105 in Krivoi Rog, together with 39 Communist officials; 511 in Pilva and Staraya Sinyava; fifty in Tartu, together with 455 local Communists; 1,107 Jewish adults and 561 ‘juveniles’, the latter killed by Ukrainian militia, in Radomysl; 627 Jewish men and 875 ‘Jewesses over twelve years’ in Berdichev; and 544 ‘insane persons’ taken from the lunatic asylum in Dvinsk ‘with the assistance of the Latvian self-defence unit’. Ten of the inmates, judged ‘partially cured’, were sterilized and then discharged. ‘After this action,’ the Report concluded, ‘the asylum no longer exists.’

***

On September 16, as Hitler spoke with such confidence at Rastenburg, a transatlantic convoy, HX 150, set sail from Halifax, Nova Scotia. It was the first convoy to be escorted by American warships. On September 17, in northern Russia, the British Royal Air Force Wing was in action for the second time. That same day, the last assault by von Leeb on Leningrad failed to break through the city’s defences; that day, he had finally to begin the despatch of his tank forces to the Moscow front. ‘There will be a continuing drain on our forces before Leningrad,’ a worried General Halder noted in his diary on September 18, ‘where the enemy has concentrated large forces and great quantities of material, and the situation will remain tight until such a time when hunger takes effect as our ally’.

Hitler was still in optimistic mood on September 17, telling his guests at Rastenburg of the future demise of Russia. The Crimea would provide Germany with its citrus fruits, cotton and rubber: ‘We’ll supply grain to all in Europe who need it.’ The Russians would be denied education: ‘We’ll find among them the human material that’s indispensable for tilling the soil.’ The German settlers and rulers in Russia would have to constitute among themselves ‘a closed society, like a fortress. The least of our stable-lads must be superior to any native.’

German forces were now on the very outskirts of Kiev, the Soviet Union’s third largest city after Moscow and Leningrad. On September 16, following four days of urgent appeals from General Kirponos to Stalin that it would soon be too late to pull back his troops from the city and its surroundings, Marshal Timoshenko had authorized the withdrawal from Kiev. It was another forty-eight hours, however, before Stalin confirmed the order. On September 18, as the belated withdrawal began, General Kirponos’s thousand-strong command column was ambushed and encircled. Hit by mine splinters in the head and chest, Kirponos died in less than two minutes. His armies fought bravely to escape the trap. Although 15,000 did succeed in breaking out, as many as half a million were taken prisoner. For the Red Army, it was a grave and massive loss of fighting strength. But the Germans were not without cause for concern of their own; that week it was announced from Berlin that 86,000 German soldiers had been killed since the invasion of Russia had begun three months earlier.

There was further cause for concern in German military circles that September, as Tito’s forces gathered strength inside German-occupied Yugoslavia. In the early hours of September 17, a British submarine, operating from Malta, landed a British agent, Colonel D. T. Hudson, on the Dalmatian coast, near Petrovac. He at once made contact both with Tito, and with the Cetnik leader, Mihailović.

A week after Hudson reached Yugoslavia, Tito’s partisans, 70,000 men in all, but with few weapons and little ammunition, captured the town of Uzice, with its rifle factory producing four hundred rifles a day. They were to hold the town for two months. Resistance in Yugoslavia, as in Russia, had begun to harass and tie down considerable numbers of German troops.