Pearl Harbour, December 1941

On the Eastern Front, the German position, so impressive on the map, was worsening daily on the ground. By mid-November 1941 it had become so cold that sentries who accidentally fell asleep at their post were found frozen to death in the morning. The Russians were better trained to survive in extreme cold. They were also defending their heartland and their capital. On November 17, near Volokolamsk, a private soldier, Efim Diskin, the sole survivor of his anti-tank battery, and himself severely wounded, destroyed five German tanks with his solitary gun. He was later awarded the medal, Hero of the Soviet Union.

The Russians were not only fighting with a tenacity which surprised their German opponents, but they were also being steadily reinforced. On 18 November, the German troops attacking Venev were themselves attacked by a Siberian division and armoured brigade, both newly arrived from the Far East with a full complement of T-34 tanks. So cold was it that the German automatic weapons would only fire single shots. As the Siberian troops advanced, in their white camouflage uniforms, ‘the panic’, a German Army report later noted, ‘reached as far back’ as Bogorodisk: ‘This was the first time that such a thing had occurred during the Russian campaign, and it was a warning that the combat ability of our infantry was at an end, and that they should no longer be expected to perform difficult tasks.’

On this very day, in North Africa, British and Commonwealth forces launched Operation Crusader. Determined to take some action to draw German pressure away from the Eastern Front, and having been alerted by the Germans’ own Enigma messages to the weakness and dispositions of Rommel’s forces, on November 18, British, Australian, New Zealand and other Commonwealth troops attacked the German line. After an initially successful defence by Rommel, the line was outflanked, forcing Rommel to withdraw to El Agheila, the point from which he had begun his attack on Egypt eight months earlier. In the Far East, however, there was a naval setback for the Commonwealth forces, when the German ocean raider Komoran, a converted cargo ship, sank the Australian light cruiser Sydney off the coast of Australia. All 645 officers and men aboard the Sydney were drowned. The Komoran also sank, but most of her crew were saved.

The Russians now began to prepare for a major offensive, to save Moscow. They were able, with great skill, to hide entirely from German reconnaissance and Intelligence eyes the forward movement of their reserves. The ‘enemy’, noted General Halder in his diary on November 18, ‘had nothing left in the rear, and his predicament probably is even worse than ours’. Those, however, whose ‘predicament’ was worse even than that of the fighting soldiers in the wintry fields of Russia or the sand blown hills of Libya, were the Red Army men, numbering as many as three million, perhaps even more, who had been taken prisoner by the Germans in the previous five months. The fate of seven thousand of these Russian prisoners-of-war was noted on November 18 by the commander of a German artillery regiment who saw them in their camp. The windows of the building in which they were being held, he wrote, ‘are several metres high and wide, and are without covering. There are no doors in the building. The prisoners who are thus kept practically in the open air are freezing to death by the hundreds daily—in addition to those who die continuously because of exhaustion’.

On November 20 the Germans captured Rostov-on-Don, less than two hundred miles from the western foothills of the Caucasus. That day, in an Order of the Day issued to all his troops, General von Manstein declared: ‘The Jews are the mediators between the enemy in our rear and the still fighting remnants of the Red Army and the Red leaders’. The German soldier in the East, in fighting the Bolsheviks, was ‘the bearer of a ruthless ideology’; he must therefore ‘have understanding of the necessity of a severe but just revenge on sub-human Jewry’.

Nine days after von Manstein issued this order, 4,500 Jews were murdered in the Crimean port of Kerch. Two weeks later, 14,300 Jews were murdered in Sevastopol. These killings were witnessed by hundreds of bystanders, and reported on in detail in the Operational Situation Reports USSR, with their distribution to between thirty and sixty senior officials and civil servants. Far more secret were the gassing experiments, which were now nearing their operational stage. ‘I spoke with Dr Heyde on the phone,’ one of the ‘euthanasia’ experts at Buchenwald concentration camp, Dr Fritz Mennecke, wrote to his wife on November 20, ‘and told him I could handle it all by myself, so no one else came today to help.’ As to the ‘composition of the patients’, Mennecke added, ‘I would not like to write anything here in this letter.’

***

On November 21, Albert Speer asked Hitler for thirty thousand Soviet prisoners-of-war, to help with the building of Berlin’s new monumental buildings. Hitler agreed. The building, he said, could begin before the war was over. Among the projects, of which Speer showed Hitler miniature models that day, were a Great Hall for the Chancellery and an Office for Goering. Hitler also drew for Speer, in ink on lined paper, the design for a Monument of Liberation to be built at Linz, on the Danube, near Hitler’s own birthplace. The monument, an imposing arch, was to be the centrepiece of a stadium holding thousands of spectators.

***

The siege of Leningrad, with its growing starvation, continued. On November 22, a column of sixty trucks, commanded by Major Porchunov, set off from Kobona and, following the tracks made by horses and sledges on the previous day, crossed the frozen waters of Lake Ladoga to Kokkorevo, with thirty-three tons of flour for the besieged city. One of the drivers, Ivan Maximov, later recalled how: ‘I was with that column. A dark and windy night shrouded the lake. There was no snow yet and the black-lined field of ice looked for all the world like open water. I must admit that an icy fear gripped my heart. My hands shook, no doubt from strain and also from weakness—we had been eating a rusk a day for four days… but our column was fresh from Leningrad and we had seen people starving to death. Salvation was there on the western shore. And we knew we had to get there at any cost’.

One truck, and its driver, were lost in the crossing, falling through the ice and disappearing under the freezing waters. Six more crossings were made in the next seven days, bringing eight hundred tons of flour to the city, as well as fuel oil. But, in those same seven days, forty more trucks had gone to the bottom. Along the road to the lakeside, German shelling also took its toll, as did the snow drifts; in three days, 350 trucks were abandoned in drifts near Novaya Ladoga. In all, 3,500 trucks were available, though at any one time more than a thousand were out of service, awaiting repairs. Nevertheless, a lifeline, albeit precarious, had been opened. It could not, however, do much to reduce the daily deaths from starvation; during November, as many as four hundred people were dying every day from starvation.

In German-occupied Warsaw, starvation in the ghetto was also a daily occurrence, to which as many as two hundred Jews succumbed daily. ‘In the street’, noted Mary Berg in her diary on November 22, ‘frozen human corpses are an increasingly frequent sight.’ Sometimes, Mary Berg added, a mother ‘cuddles a child frozen to death, and tries to warm the inanimate little body. Sometimes a child huddles against his mother, thinking that she is asleep and trying to awaken her, while, in fact, she is dead.’

***

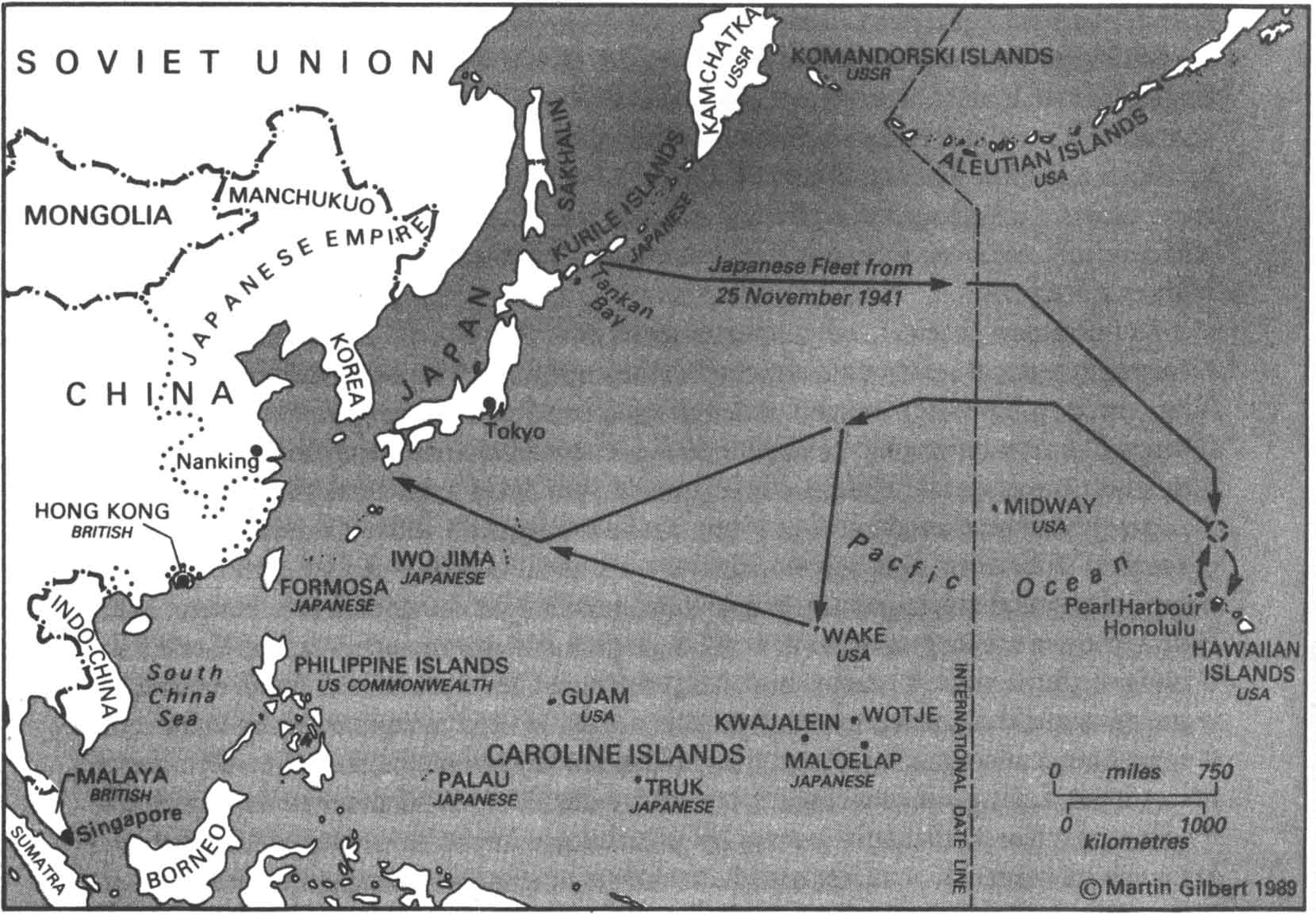

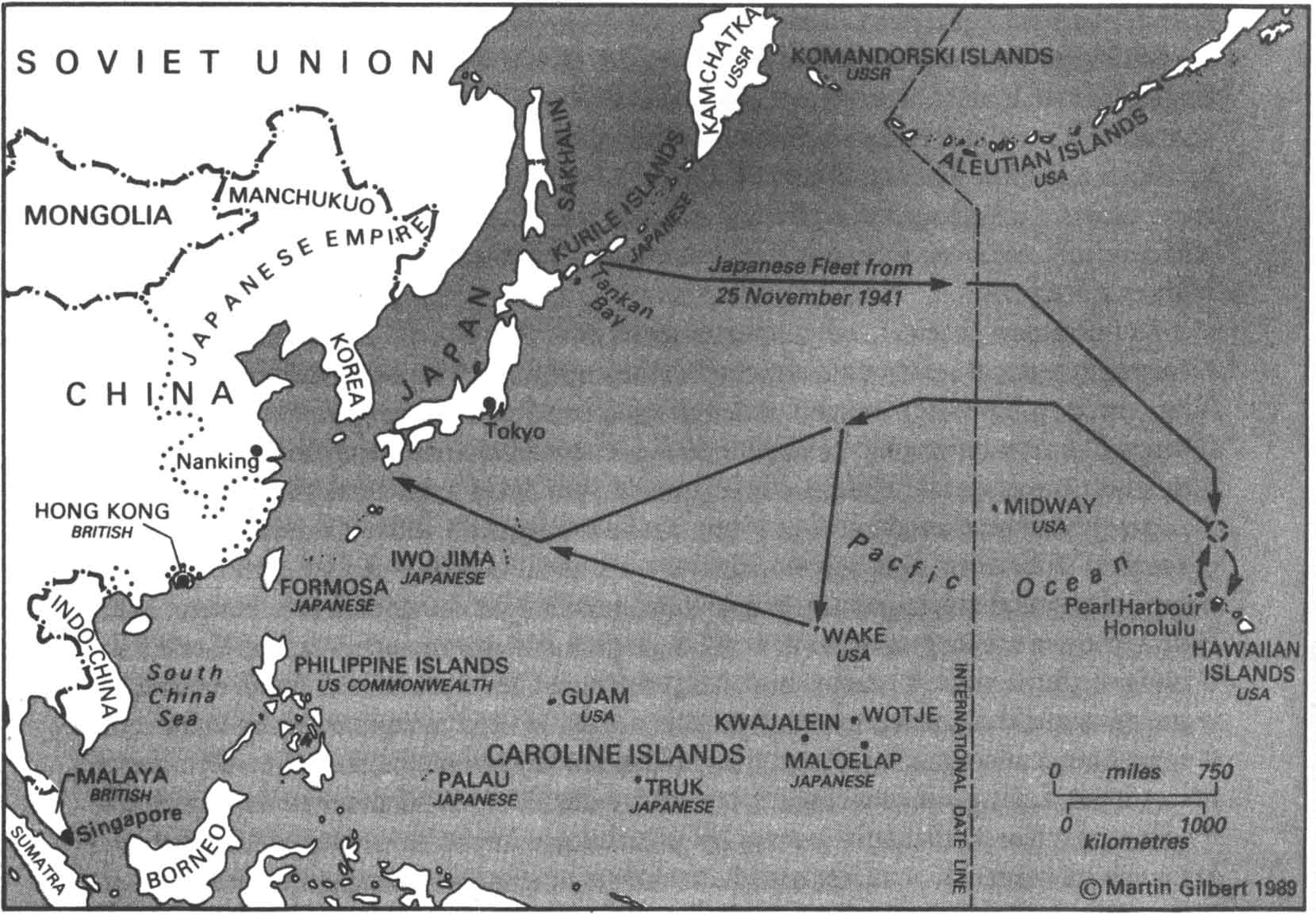

The Japanese Government now hid its preparations behind a flurry of negotiations in both Washington and London. ‘I am not very hopeful,’ Churchill telegraphed to Roosevelt on November 20, ‘and we must all be prepared for real trouble, possibly soon.’ Two days later, behind an unpenetrated veil of secrecy, and as the American negotiators continued in Washington to discuss the latest Japanese document with their British, Australian and Dutch counterparts, the Japanese put into effect Operation Z, the assembly of the Japanese First Air Fleet in Tankan Bay in the Kurile Islands. It was an impressive, if unseen force: six aircraft carriers, a light cruiser and nine destroyers, supported by two battleships, two heavy cruisers, and three submarines for reconaissance.

As Japanese naval forces gathered in the northern Pacific, across the globe, in the South Atlantic, November 22 also saw the final day in the career of the German commerce raider Atlantis. The most effective German raider of the war, with more than 140,000 tons of Allied merchant shipping to its ‘credit’, it was caught by the British cruiser Devonshire while refuelling a German submarine, and sunk.

***

On the Moscow front, German forces advanced on November 23 to within thirty miles of the capital, reaching the village of Istra, a centre of Russian Orthodox pilgrimage known to the faithful as New Jerusalem. On the following day, the towns of Klin and Solnechnogorsk fell to a German assault, bringing German troops astride the main highway from Moscow to the north.

***

In the Far East, a sense of impending danger had begun to pervade the Anglo-American counsels; Canadian troops were on their way to Hong Kong, and, on November 24, the authorities in Washington informed all Pacific commanders that there was a possibility of a ‘surprise aggressive movement in any direction, including an attack on the Philippines or Guam’. No mention was made of Pearl Harbour.

To reverse the tide of defeat in North Africa, the Germans despatched two ships, the Maritza and the Procida, to Benghazi, with fuel of decisive importance for the German Air Force. News that the ships were on their way was sent by a top secret Enigma signal, which, on November 24, was decrypted at Bletchley. Churchill himself urged action on the basis of the decrypt. Within twenty-four hours, both ships were sunk. A further Enigma message, decrypted on November 29, revealed that, as a result of the sinking of the two ships, the fuel supplies for the air forces supporting Rommel were in ‘real danger’. The British Commander-in-Chief, General Auchinleck, at once exhorted his troops, in an Order of the Day issued on November 25: ‘Attack and pursue. All out everywhere.’ Churchill telegraphed that same day to Auchinleck: ‘A close grip upon the enemy by all units will choke the life out of him.’

As the British forces struggled to take advantage of their Intelligence knowledge of Rommel’s weakness, Hitler ordered several German submarines to the Mediterranean to redress the British successes against Rommel’s supply shipping. On November 25, one of these submarines, U-331, commanded by Lieutenant von Tiesenhausen, sank the British battleship Barham off Sollum; 868 men were drowned. Two days later, the Australian sloop Parramatta was torpedoed off Tobruk, and 138 men were drowned.

***

In Berlin, there was a celebration on November 25, the fifth anniversary of the drafting of the Anti-Comintern Pact. A considerable array of States were now committed to the overthrow of Communist Russia: Germany, Italy, Hungary, Spain, Bulgaria, Croatia, Denmark, Finland, Roumania and Slovakia.

On November 25, the Russian defenders south of the capital were pushed back through Venev to the village of Piatnitsa, only four miles from the River Oka bridge at Kashira. To the north of Moscow, advance German units crossed the Volga—Moscow canal at Yakhroma and Dimitrov, threatening the capital with encirclement. After the fall of the village of Peshki, east of Istra, and a further Soviet retreat to Kryukovo, the Soviet commanding officer, General Rokossovsky, was given the order: ‘Kryukovo is the final point of withdrawal. There can be no further falling back. There is nowhere to fall back to.’

If Stalin was worried, so was Hitler; on November 25 his adjutant, Major Engel, noted after a long evening discussion: ‘The Führer explains his great anxiety about the Russian winter and weather conditions, says we started one month too late. The ideal solution would have been the surrender of Leningrad, the capture of the south, and then if need be a pincer round Moscow from south and north, following through in the centre’. Engel added: ‘Time is his greatest nightmare now’.

In Germany itself, the experiments in killing by gas continued; on November 25, at Buchenwald concentration camp, Dr Fritz Mennecke received, as he wrote to his wife, ‘our second batch of 1,200 Jews’, but, he explained to her, ‘they did not have to be “examined”.’ No medical examination was needed, only the taking out of their files, to note down their imminent departure. The 1,200 Jews were then sent to a clinic at Bernburg, a hundred miles away, and gassed. A further 1,500 Jews, citizens of Berlin, Munich and Frankfurt, had been deported from Germany a few days earlier to Kovno. They had been told that they were being sent to a work camp. But instead, after being locked in underground cellars at the Ninth Fort for three days, without food or drink, freezing amid ice-covered walls and icy winds, on November 25 they were led, frozen and starving, to the pits that had been prepared for them, and ordered to undress. In their suitcases were found printed announcements urging them to prepare for a ‘difficult’ winter. ‘They did not want to undress,’ a Kovno Jew, Dr Aharon Peretz, was later told, ‘and they struggled against the Germans.’ But it was a hopeless, unequal struggle, and they were all shot, the Special Task Force recording with its usual precision the day’s death toll: ‘1,159 Jews, 1,600 Jewesses, 175 Jewish children’. Four days later, it was ‘693 Jewish men, 1,155 Jewesses, 152 Jewish children’, described as ‘settlers from Vienna and Breslau’, who were taken to the Ninth Fort and shot; a total death toll in the two ‘actions’ of nearly six thousand people.

***

On November 25, from Washington, Admiral Stark informed Admiral Kimmel that neither Roosevelt nor Cordell Hull would be surprised if the Japanese were to launch a surprise attack. An attack on the Philippines would be ‘the most embarrassing’. Stark thought that the Japanese would probably attack the Burma Road.

Admiral Kimmel, in command at the mid-Pacific base at Oahu, of which Pearl Harbour was a part, was at that very moment in discussions with General Short about sending warships away from Pearl Harbour, in order to reinforce Wake Island and Midway island. ‘Could the Army help out the Navy?’ Kimmel asked Short. But it seemed that the army had no anti-aircraft artillery to spare.

American Intelligence knew, from an intercepted Japanese diplomatic message, that the rulers of Japan had set November 25 as their deadline for the working of diplomacy, and for an agreed end to the American economic sanctions against them. If no solution was agreed by then, the intercepted message read, ‘things will automatically begin to happen’. What those ‘things’ were was not explained, but on November 25 Japanese troop transports were sighted off Formosa, heading towards Malaya. On November 26, unobserved by the Americans, the Japanese First Air Fleet sailed from the Kurile Islands, towards the International Dateline, maintaining complete radio silence.

Pearl Harbour, December 1941

As Japanese warships made what was in fact their way towards Pearl Harbour, the United States gave the Japanese negotiators in Washington the American terms for a settlement: Japan must give up the territory she occupied in both China and Indo-China, must end recognition of the Chinese ‘puppet’ Government at Nanking, and must withdraw from the Axis.

On November 27, Roosevelt and his advisers decided that Japan was now bent on war. ‘Hostile action possible at any moment,’ the War Department in Washington telegraphed to General MacArthur in the Philippines. ‘If hostilities cannot be avoided,’ the telegram continued, ‘United States desires that Japan commit the first overt act.’ That same day, Admiral Stark, chief of naval operations in the United States Supreme Command, sent to all the commanders of the American Asian and Pacific fleets a ‘warning of state of war’.

***

On the Moscow front, Soviet forces were at last able, on November 27, to halt the German advance and, at certain points, to push the Germans back two or three miles. ‘Prisoners taken’, Zhukov was able to report that day to Stalin. Soviet partisan operations were also continuous. On the night of November 27, a unit of the SS Death’s Head Division was attacked in its billets south of Lake Ilmen by a partisan band, which burned the SS vehicles and buildings, killing four Germans, seriously wounding twelve, and disappearing, leaving a burning camp behind them.

‘New forces have made their appearance in the direction of the Oka river,’ General Halder noted that November 27. North-west of Moscow, also, ‘the enemy is apparently moving new forces’. These Soviet reinforcements were not large units, Halder added, ‘but they arrived in endless succession and caused delay after delay for our exhausted troops’.

On November 28, the Germans were forced to give up Rostov-on-Don, their first serious setback on the Eastern Front. Between Dimitrov and Zagorsk, twelve Soviet ski battalions were assembling in reserve, opposite the Germans who now held the whole Moscow—Kalinin road. Southeast of Moscow, despite the German bombing of railway lines, the Soviet Tenth Army was likewise being brought forward, on November 28 from Shilovo to Ryazan. ‘The enemy movements to Ryazan from the south are continuing,’ General Halder noted in his diary on the following day.

In Berlin, Hitler learned on November 28 that the German siege of Tobruk had been broken, and that Rommel was in retreat. That same day, he received the Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin el-Husseini, who told him that ‘the Arab world was firmly convinced of a German victory, by virtue not only of the large Army, brave soldiers and brilliant military strategists at Germany’s disposal, but also because Allah could never grant victory to an unjust cause’. In reply, Hitler reminded the Mufti that ‘Germany had declared an uncompromising war on the Jews.’ Such a commitment, he said ‘naturally entailed a stiff opposition to the Jewish homeland in Palestine’. Germany was ‘determined’, Hitler added, ‘to challenge the European nations one by one into a settlement of the Jewish question and, when the time came, Germany would turn to the non-European peoples with the same call’.

After gaining ‘the southern exit of the Caucasus’, Hitler told the Mufti, he would offer the Arab world ‘his personal assurance that the hour of liberation had struck’. Thereafter, he explained, ‘Germany’s only remaining objective in the region would be limited to the annihilation of the Jews living under British protection in Arab lands.’

The German march to the Caucasus was, temporarily at least, halted. Following the loss of Rostov-on-Don, the Germans were forced to evacuate Taganrog on November 29. That day, in the village of Petrishchevo behind the Moscow front, as part of their attempt to halt the growing number of partisan attacks, the Germans hanged an eighteen-year-old Soviet girl, Zoia Kosmodemianskaya. ‘She set fire to houses’, read the placard around her neck as she was led to execution. Her own last words, as she was led to the scaffold, were to one of the German soldiers accompanying her: ‘You can’t hang all 190 million of us.’

Hitler’s difficulties were now considerable. On November 29, Dr Todt, returning to Berlin from the Russian front, told him bluntly: ‘Given the arms and industrial supremacy of the Anglo-Saxon powers, we can no longer militarily win this war.’ That day, in southern Russia, the Germans were forced, after attacks by the Red Army which included repeated assaults over German minefields and into machine gun positions, to withdraw behind the River Mius. Reinforcements were hurried south from the German reserves in Kharkov; reserves that could not now be used against Moscow. ‘Further cowardly retreats are forbidden’, Hitler telegraphed to Field Marshal von Kleist.

Whatever the problems confronting the German troops in Russia, the killing of Jews continued. On November 29, a thousand German Jews, who had been deported from Berlin two days earlier, reached Riga. They were kept in the locked wagons all night, and then, at 8.15 on the morning of November 30, the survivors of the journey were taken into the nearby Rumbuli forest, and shot. Later that day, at 1.30 p.m., Himmler telephoned to Heydrich from Hitler’s headquarters at Rastenburg, to which Hitler had just returned to say that there should be ‘no liquidation’ of this convoy. But it was too late; Heydrich replied that all the Jews on the convoy had been shot that morning.

Nineteen more trains were to reach Riga with German Jews during the next month. These Jews were taken not to Rumbuli, but to the Riga ghetto, where they were put to forced labour for the Germans. Place in the ghetto had already been found for them by the despatch, to Rumbuli earlier on the morning of 30 November, amid scenes of the utmost cruelty and terror, of nine thousand of Riga’s Jews; all were killed during ‘a shooting action’, as it was described in Operation Situation Report USSR No. 151. A further 2,600 Riga Jews were murdered at Rumbuli a few days later.

Old, sick and frail Jews who could not manage to march the five miles from the Riga ghetto to the Rumbuli forest were shot down as they stumbled, fell, or sat exhausted on the ground; one such victim was the eighty-one-year-old doyen of Jewish historians, Simon Dubnov. According to one account, his last words as he lay dying were an injunction to his fellow Jews: ‘Write and record!’

It was also on 30 November, the day of the ‘shooting action’ in Riga, that the first Jewish deportees, a thousand women, children and old people from Prague, reached a new German concentration camp at Theresienstadt, thirty-five miles north of Prague. There in the huts and barracks of an eighteenth century fortress, uprooted from their homes, penniless, deprived of all but their most personal belongings, overcrowded and ill-fed, they were to be joined during the coming weeks by almost all the remaining Jews of Vienna, Berlin and a dozen other German and former Czechoslovak cities. None was to be murdered while at Theresienstadt; but thirty-two thousand were to die there of hunger and disease.

***

In Leningrad, during the month of November, eleven thousand citizens had died of starvation, and 522 had been killed during the daily German shelling of the city. With the German occupation of Mga and Schlüsselburg secure, the only way by which supplies could reach the city was by truck over the ice of Lake Ladoga. On December 1, the siege of Leningrad entered its ninety-second day. That day Vera Inber saw a sight she had not seen before, a corpse on a child’s sledge. Instead of being placed in a coffin, the body had been tightly wrapped in a sheet. That December, the deaths from starvation in the city rose from four hundred to more than fifteen hundred every day.

The statistics of death are numbing; on December 1, at Buchenwald, Dr Fritz Mennecke noted that although he had to begin work half an hour late in filling in the forms which sent Jews to Bernburg, and to their death by gassing, ‘a record was broken. I managed to complete 230 forms, so that now a total of 1,192 are complete.’ That same day, SS Colonel Karl Jaeger reported to Berlin that his Special Task Force had ‘reached the goal of solving the Jewish problem in Lithuania’. Colonel Jaeger’s ‘goal’ was far in excess of Dr Mennecke’s ‘record’. In all, Jaeger reported, his Special Task Force units had killed 229,052 Jews in Latvia and Lithuania since June, and a further thousand in Estonia. The only ‘remaining’ Jews, he explained, were those in the ghettos of Vilna, Kovno and Siauliai, employed in various German factories and at other labouring tasks.

That night, in conversation with Walther Hewel, Hitler declared: ‘Probably many Jews are not aware of the destructive power they represent. Now, he who destroys life is himself risking death. That’s the secret of what is happening to the Jews.’

***

On December 1, the Germans made two desperate bids to break through the Moscow defences. One was at Zvietkovo, west of the capital and the other towards Kolomna, from the south. But the Soviet defensive ring held, and a relentless German tank assault at Naro-Fominsk was driven back. As December 2 dawned, many German soldiers, unable to face a second day of fire and ice, screamed that they could not go on. There was also now a new rearward Soviet defence line, behind which, as the Moscow front line soldiers held on tenaciously, fifty-nine rifle divisions and seventeen cavalry divisions were grouping for a massive counter-attack, in avast arc from Vytegra on Lake Onega to Astrakhan on the Caspian Sea, passing through the Volga cities of Kostroma, Gorky and Saratov.

As Soviet reinforcements gathered, the Germans were unaware even of their existence. ‘Overall impression’, General Halder noted on 2 December, ‘enemy defence has reached its peak. No more reinforcements available.’ That day, in a blinding snowstorm, which reduced visibility to fifty feet and even less, a German reconnaissance battalion pushed its way forward through Khimki, just beyond the northern suburbs of Moscow, and only twelve miles from the Kremlin. But Russian workers, hastily armed, were rushed northward from the city, and drove the German unit out.

Throughout the day, six miles south of the Moscow-Mozhaisk highway, German tanks had tried to break through towards Moscow at the village of Akulovo, when, briefly, German troops were within sight of the tall spires of the Kremlin. But twenty-four hours later, they were driven from Akulovo. The Russian defence of Moscow could not be broken.

In the south, the Germans had been forced to retreat to Mariupol. But in the Crimea they not only consolidated their positions, but murdered Jews and Soviet prisoners-of-war indiscriminately, meticulously recording the total Jewish death toll as 17,645, as well as 2,504 local Krimchak Jews who could trace their Russian origins back more than a thousand years. In addition to the Jews, this same Operational Situation Report USSR No. 150 listed ‘824 Gypsies and 212 Communists and partisans’, all shot; and went on, without explaining the higher figure: ‘Altogether 75,881 persons have been executed.’ The number of captured Soviet soldiers executed in those days was not specifically recorded.

***

On December 1, as Japanese troop transports crossed the South China Sea from Formosa, the British declared a state of emergency in Malaya. On the following day, the Japanese First Air Fleet, still sailing eastward across the Pacific, received the coded order which established that Pearl Harbour was now its target. That same day, December 2, a telegram was sent from Tokyo to the Japanese Consulate in Hawaii, asking if there were any barrage balloons over Pearl Harbour, and if torpedo nets were in use there. To those in Washington who decoded this telegram, it seemed a routine Intelligence enquiry.

On the day of this Tokyo request for information about the defences of Pearl Harbour, a British battleship, the Prince of Wales, arrived in Singapore, together with the cruiser Repulse and four destroyers. A third major warship, the aircraft carrier Indomitable, whose aircraft, a squadron of nine new Hurricane fighters, would have provided air cover for the battleship and its cohorts, was not however with them; it had run aground in the West Indies, and needed twenty-five days before repairs could be completed.

By an incredible coincidence, the British ships which had just reached Singapore had been given the code name Force Z. The move of the Japanese First Air Fleet towards Pearl Harbour was Operation Z.

On December 3, Japanese Intelligence received a report from Consul-General Kita in Hawaii about the American warships then at anchor at Pearl Harbour, including the battleships Oklahoma and Nevada, and the aircraft carrier Enterprise. Reaching a point 1,300 miles north-west of Hawaii, the Japanese First Air Fleet turned south-east, steaming towards its unsuspecting target.

***

Between November 16 and 4 December, 85,000 Germans had been killed on the Moscow front, the same number of troops as had died on the whole Eastern Front between mid-June and mid-November. But Hitler’s order not to withdraw was obeyed; and with the arrival of a hundred fresh Russian divisions, a further 30,000 German soldiers were killed south of Moscow, where the Tula salient threatened the capital from the south. Despite these enormous losses, the German line held; Hitler, cheated of a swift march into Moscow, could still see on the map a German line full of menace to the Russian capital.

On December 3, the Russians were finally forced to evacuate their garrison at Hango, the Finnish naval base which they had occupied early in 1940, and which had been under Finnish siege since June 29. Not only was Hango lost but, south of Moscow, in yet another effort to break through to the capital, the Germans launched an attack on December 4 between Tula and Venev. That night, however, the temperature dropped to an incredible thirty-five degrees centigrade below zero, and in the morning their tanks would not start nor their guns fire, while frostbite brought agony to thousands of German soldiers, whose boots were not designed, as were the Russian boots, for such extremes of cold.

The Eastern Front, December 1941

The Germans had hoped to defeat Russia before the onset of winter. For this reason, they were not equipped for winter fighting. Nor could a last-minute order to commandeer women’s fur coats throughout Germany be effective in time to avert the terrifying effect of extreme cold during those first few days of December.

Meanwhile, three Russian reserve armies, fresh from the rear and undetected by German Intelligence, prepared to launch an offensive. Thrusting forward with superior tanks, driven by a desire to free their capital from the threat of conquest, better equipped for the biting cold, at three o’clock on the morning of December 5, shielded by a ferocious blizzard against which the Germans could hardly stand, and with snow lying more than a yard thick, the Russian soldiers began to drive the Germans back. In all, eighty-eight Russian divisions were in action that day, against sixty-seven German divisions, along a five-hundred-mile front from Kalinin in the north to Yelets in the south.

Counter-attacking from the north, Soviet forces crossed the frozen Volga near Kalinin. Further south, crossing the Moscow canal from the east, they drove the Germans from Yakhroma, liberating the railway line from Moscow to the north.

Despite Hitler’s order that his armies should hold on at all costs, on December 5 they were driven back slowly, painfully, but inexorably, two miles, five miles and—north of Moscow, where the threat had been closest—eleven miles from the Russian capital. That day, Britain declared war on Hitler’s three partners in the war against Russia—Finland, Hungary and Roumania. Simultaneously, with Britain’s declaration of war, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Canada did likewise.

The spectre of a German failure to capture Moscow was no deterrent to the relentless imposition of tyranny behind the lines. On December 4, a decree had been published in Berlin which stated that Poles and Jews in the eastern territories who sabotaged or disobeyed, or incited others to disobey, ‘any orders or decrees passed by the German authorities’ would be punished by death. On the following day Himmler signed a letter for the creation, from concentration-camp inmates, of a reserve of five thousand skilled stonemasons and ten thousand bricklayers, ‘before peace is concluded’. ‘These workers are needed’, Himmler explained, ‘since the Führer has already ordered that the Deutsche Erd und Steinwerke company, as an undertaking of the SS, shall deliver at least 100,000 cubic metres of granite a year, more than was ever produced by all the quarries in the old Reich’.

Such plans were of no help to the German tank crews now being bombarded that week in the East by the full force of the unexpected Soviet offensive. Not only did German soldiers have to light fires in pits under their tanks for as much as four hours, in order to thaw out their engines sufficiently to bring them into action, but, in conflict with the Soviet T-34 tanks, the German anti-tank shells were useless.

***

On the morning of Saturday 6 December, a newly formed Government subcommittee met in Washington. Given the code name ‘S-1’, its task was to establish, within the following six months, if an atomic bomb could be produced in the United States and, if so, when and at what cost. Shortly after midday, in the Navy’s Cryptographic Department, also in Washington, a member of the staff, Mrs Dorothy Edgers, translated a secret diplomatic message, sent from Tokyo four days earlier to Consul-General Kita in Honolulu, by the ‘Magic’ code which the Americans had long ago broken, telling Kita that, from that time on, he must send regular reports of all ship movements, berthing positions and torpedo netting at Pearl Harbour. Fully alarmed, Mrs Edgers began translating other intercepts, all of which were in similar vein. Then, at three o’clock that afternoon, she presented her translation to the Chief of the Translation Department, Lieutenant Commander Alvin Kramer. After a few minor points of criticism of her translations, Kramer told her: ‘We’ll get back to this on Monday’.

‘Monday’ was December 8. By the time it came, no further studying was needed. On Sunday, December 7, Japanese forces struck, in ruthless succession, at Malaya, Pearl Harbour, the Philippines and Hong Kong, all within seven hours. The road to global war had been traversed.