The Eastern Front, March 1942

The New Year of 1942 opened inauspiciously for the Allies. In the Kerch peninsula, German forces pushed back the Russian parachutists who had landed on this eastern extremity of the Crimea. In the Philippines, American and Filipino troops were being pushed back into the Bataan peninsula. In Malaya, Japanese forces, continuing their southern advance, occupied Kuantan. In Germany, 1942 was triumphantly declared the ‘Year of Service in the East and on the Land’; a total of 18,000 Hitler Youth leaders from Germany serving in Poland and the western Ukraine. They were sent to form a nucleus of a future Germanic settlement in the East. During the year, several hundred young Dutch, Norwegian, Danish and Flemish volunteers were to join them: these ‘Eastern Volunteers of Germanic Youth’ were likewise to be a nucleus of the New Order. It was a New Order typically marked, on 1 January 1942, by the final disappearance of the Zagreb synagogue, pride of the Croat capital’s 12,000 Jews, which had been demolished stone by stone over a period of four months.

There were also several acts of defiance that January 1. The most public was a declaration, issued by Churchill and Roosevelt in Washington, and signed by twenty-six nations, requiring the signatories to employ their full resources against the Axis, and not to make peace separately. Calling themselves the ‘United Nations’, and headed by Britain, the United States and the Soviet Union, these twenty-six nations declared that the aim of their struggle and their unity was ‘to ensure life, liberty, independence and religious freedom, and to preserve the rights of man and justice’. In the Vilna ghetto, 150 young Jews gathered that January 1, not to mourn the 60,000 murdered Jews of their city, but, on behalf of the 20,000 who were still alive behind the guardhouses and the barbed wire, to declare: ‘Hitler plans to destroy all the Jews of Europe, and the Jews of Lithuania have been chosen as the first in line. We will not be led like sheep to the slaughter!’

In German-occupied Europe, it was only slowly that even the smallest of steps could be taken to challenge German power. One such step was taken that January 1 when the former Mayor of the French city of Chartres, Jean Moulin, who had escaped four months earlier to Britain, was parachuted back into France. His task was to try to unify the various and disparate Resistance groups, and to set a course of co-ordinated action. Known as ‘Max’, Moulin brought with him on his mission, hidden in the false bottom of a matchbox, a warm personal message from General de Gaulle to the Resistance leaders.

On New Year’s Day 1942, in the Far East, Japanese forces already ashore on Borneo attacked the island of Labuan. It was a day he would not easily forget, the British Resident, Hugh Humphrey, later wrote, ‘for I was repeatedly hit by a Japanese officer with his sword (in its scabard) and exhibited for twenty-four hours to the public in an improvised cage on the grounds that, before the Japanese arrived, I had sabotaged the war effort of the Imperial Japanese Forces by destroying the stocks of aviation fuel on the island….’ Humphrey was to remain a prisoner of the Japanese until the end of the war.

***

At Bletchley, where 1,500 British scholars and academics were now decrypting and analysing the German Enigma messages, the first day of January brought a remarkable success, the breaking of four separate Enigma keys: ‘Pink’, used by the German Air Force command for messages of the highest secrecy, and ‘Gadfly’, ‘Hornet’ and ‘Wasp’, used by three of the German air corps. On the following day, 2 January, a fifth key was broken; known at Bletchley as ‘Kite’, it carried the German Army’s most secret supply messages from Berlin to the Eastern Front.

It was on the Eastern Front, on January 2, that Hitler issued an order forbidding his Ninth Army, which had just evacuated Kalinin, to make any further withdrawals. Not ‘one inch of ground’ was to be given up. But the Red Army was not to be deterred in its repeated attacks by any such instructions to its enemy; that same day, the Thirty-ninth Russian Army broke through the German front line north-west of Rzhev. Such victories were helped by the growing Russian efforts behind the lines. ‘Repeatedly’, the Second Panzer Army reported on January 2, ‘it has been observed that the enemy is accurately informed about the soft spots in our front and frequently picks the boundaries between our corps and divisions as points of attack.’ Russian civilians, the report added, were crossing between the lines, and passing back information. ‘The movement of the inhabitants between the fronts’, this report concluded, ‘must, therefore, be prevented by all possible means.’

***

In Washington, Roosevelt and Churchill presided jointly on January 2 over a meeting, the main decision of which was in due course to overshadow all tactical manoeuvres: a staggering increase in the American arms programme. Instead of the target of 12,750 operational aircraft laid down by their Staffs a mere three weeks earlier, 45,000 were to be built by the end of 1943. Instead of 15,450 tanks, 45,000 were to be built; instead of 262,000 machine guns, half a million. All other weapons of war were to be increased in quantity by an average of seventy per cent.

Such plans held a long term threat for the Axis powers; but in January 1942 it was not clear that the Allied powers would have any such long term. On January 2, Japanese forces entered the Philippine capital of Manila. On January 3, General Marshall was advised by the American Army planners that there were insufficient forces to send a relief expedition to the embattled Philippines. On January 4, Japanese aircraft struck at Rabaul, a strategic base in the Bismarck Archipelago, guarded by 1,400 British troops.

In German-occupied Europe, there was a courageous protest on January 5 by the Dutch Council of Churches, against what they described as the ‘complete lawlessness’ of the German treatment of the Jews; but, despite the protest, round-ups for forced labour and expulsion from several towns and villages into Amsterdam continued. January 5 also saw the escape from the German prisoner-of-war camp at Colditz of two Allied officers, the Englishman Airey Neave and the Dutchman Tony Luteyn; both reached the safety of Swiss soil within the next few days. Reaching Gibraltar from Britain on January 5, an Englishman, Donald Darling, code name ‘Sunday’, organized a secret overland communication route to France, enabling escaped Allied prisoners-of-war to travel from Marseilles to Barcelona, then on to Gibraltar or Lisbon. ‘Sunday’ was substantially helped in this by ‘Monday’, a former British diplomat in Berlin, Michael Creswell, who based in Spain, would when necessary cross the Pyrenees into France to co-ordinate the escape lines.

In German-occupied France, resistance was fitful but growing. On January 7 a French policeman guarding a German Army garage was shot dead. Many Frenchmen feared that such acts of defiance were futile, provoking reprisals and a harsher occupation. But for those who carried out such acts, the will to strike, and to be seen to strike, was strong, overriding caution and fear.

***

On January 7, in Yugoslavia, the Germans launched their second anti-partisan offensive, driving Tito’s forces from Olovo, to which they had been driven less than six weeks earlier, to Foca, fifty miles to the south. But although forced to flee southward, and suffering heavy losses, the partisans retained their determination to fight on.

On the Eastern Front, January 7 saw the launching of a Soviet counter-offensive north of Novgorod. Much of the fighting took place across a frozen swamp. Thousands of German soldiers were unable to fight because of frostbite. Amputations, and even double amputations, were frequent. Because of a severe shortage of blankets, wounded men froze to death even in field hospitals; each night the temperature fell to minus forty degrees centigrade. After five days of battle, the German commander, Field Marshal von Leeb, asked permission to pull back from the exposed pocket at Demyansk. Hitler refused, and 100,000 German soldiers were soon surrounded. Von Leeb resigned; nor was he to take any further active part in the war.

As the Red Army pressed the Germans back mile by mile, the Japanese were sweeping all before them in massive thrusts. On January 10, in Malaya, the British were forced to abandon Port Swettenham and Kuala Lumpur. In the Philippines, Bataan was under sustained Japanese attack, preceded by an air drop of leaflets calling upon the defenders to surrender. On Dutch Borneo, substantial Japanese forces, supported by two heavy cruisers and eight destroyers, landed on Tarakan; the island, with its oilfields, was under complete Japanese control within twenty-four hours. Also captured on January 11, by Japanese naval parachutists, was the Dutch Celebes city of Manado, an essential airbase for the onward southern assault.

The Eastern Front, March 1942

***

Swiftly, and with ruthless cruelties towards its prisoners, the Japanese Army, supported by powerful warships, moved from island to island. An Allied soldier who surrendered might be made a prisoner-of-war. He might equally be held captive for a few hours, and then, in defiance of all known rules of war, be bayoneted to death. Ruthlessness, coming so suddenly to South-East Asia, had already been commonplace against Russian prisoners-of-war on the Eastern Front for half a year. On January 12, in Kiev, the executions began, over a twelve day period, of what the Operational Situation Report USSR No. 173 described as ‘104 political officials, 75 saboteurs and looters, and about 8,000 Jews’. In Kovno, five thousand Jews, brought earlier by train to the former Lithuanian capital from Germany and Austria, were taken on January 12 to the Ninth Fort and shot. In Odessa, the deportations began that day of 19,582 Jews, most of them women, children and old people, to concentration camps near Balta. They were sent to the camps in cattle trucks. Those who died in the trains, as dozens did, were taken off at the station of Berezovka, their corpses put in heaps, petrol poured over them, and the bodies burned before the eyes of their families. Eye-witnesses later recalled that among those burned on the pyres were several who were not yet dead. Within the next year and a half, more than fifteen thousand of the deportees were to die, most of them the victims of starvation, severe cold, untreated disease or repeated mass executions in which hundreds would be shot at a time.

On January 12 there was also an extension of the war at sea, when the British merchant ship Cyclops was torpedoed off the eastern seaboard of the United States. She had been steaming independently and unescorted along the regular coastal route. Her sinking marked the start of Operation Drum Roll, a new, and for the Allies a disastrous, phase of the war at sea. The American East Coast towns were all well lit; the coastal resorts illuminated. Taking advantage of this, the German submarine commanders lay on the bottom by day, then surfaced at dusk to pick off their targets silhouetted against the lights of the coastal towns. War had come to the United States; but it was offshore, and thus remote to the majority of the population.

By the end of the month, forty-six Allied merchant ships had been sunk off the American coast, a total of 196,243 tons of ships and supplies.

***

Details of the killings in German-occupied Poland and western Russia had begun to reach, and to horrify, the Allied governments, including those in exile from the very lands in which the tyranny was at its most intense. On January 13 the representatives of nine occupied countries, meeting in London, signed a declaration that all those guilty of ‘war crimes’ would be punished after the war. Among the signatories were General Sikorski for Poland and General de Gaulle for France. Among their ‘principal war aims’, they declared, was ‘the punishment, through the channels of organized justice, of those guilty of, or responsible for, these crimes, whether they have ordered them, perpetrated them, or participated in them’.

No day passed without the perpetration of crimes against defenceless civilians; on January 14, the day after the London Declaration, in the White Russian village of Ushachi, 807 Jews were driven to the edge of a pit and shot. Even as several dozen of them lay mortally wounded and in agony, amid the blood and corpses, peasants who had witnessed the execution clambered down into the pit to pull what gold they could from the teeth of the dead and dying. That same day, a further 925 Jews were murdered in the nearby village of Kublichi; again, local peasants searched the corpses for gold.

Hitler’s thoughts that week were not on Russia alone: ‘I must do something for Königsberg,’ he told his guests on January 15. ‘I shall build a museum in which we shall assemble all we’ve found in Russia. I’ll also build a magnificent opera house and library.’ He would also build a ‘new, Germanic museum’ in Nuremberg, and a new city at Trondheim, on the coast of Norway.

***

On January 15 the Japanese reached the northernmost mountains of the Bataan Peninsula. ‘Help is on the way from the United States,’ General MacArthur assured the men now battling for survival. ‘Thousands of troops’, he told them, ‘and hundreds of planes are being despatched.’ But no such reinforcements were on their way; nor, with Manila Bay under Japanese blockade, would they have been able to secure an easy access, even assuming that they could have crossed the Pacific without crippling loss. The only American troops travelling to a new war zone that day were the four thousand members of General Russell P. Hartle’s 34th Division, who, having just crossed the Atlantic, became the first United States servicemen to arrive in Britain. At that very moment, Churchill was returning by flying boat from the United States to Britain; at dawn on January 17, when the flying boat deviated slightly from its course, it came to within five or six minutes’ flying time of the German anti-aircraft batteries at Brest, in German-occupied France. The error was corrected; but, in turning sharply northward, the flying boat seemed to the radar watchers in Britain to be a ‘hostile bomber’ coming from Brest. Six aircraft were sent up with orders to shoot down the intruder. Fortunately, as Churchill later reflected, ‘they failed in their mission’.

Less fortunate on January 17 was the British destroyer Matabele; on escort duty with a Murmansk convoy, she was torpedoed and sunk, with the loss of 247 officers and men.

On the Eastern Front, the Red Army now embarked upon a new and decisive tactic; beginning on January 18, and continuing for six days, a total of 1,643 Soviet parachute troops were dropped behind the German lines south-east and south-west of Vyazma. Linking up with partisan units, they began to harass and disrupt the German lines of communication and supply, forcing substantial numbers of German troops to be diverted to anti-partisan activity. On January 20, in the central sector of the front, Soviet troops recaptured the German positions at Mozhaisk, thereby further protecting Moscow from the danger of a direct assault. That same day, as far back as the railway line between Minsk and Baranowicze, the Germans reported Soviet partisan attacks on German railway guards.

It was on January 20, in the Berlin suburb of Wannsee, that senior German officials met to discuss the final and complete destruction of as many of Europe’s Jews as possible. Among the Germans present, summoned there by Heydrich, was the newly appointed State Secretary in the Reich Ministry of Justice, Roland Freisler, and a leading Nazi member of the German Foreign Ministry, Martin Luther, whose task was to persuade the governments of Europe to co-operate in what was called, deceptively, ‘the Final Solution of the Jewish Question’. The aim, Heydrich explained, was that all eleven million Jews in Europe should ‘fall away’. To find them, Europe would be ‘combed from West to East’. The representative of the General Government, Dr Joseph Bouhler, had ‘only one favour to ask’, that the ‘Jewish question’ in the General Government ‘be solved as rapidly as possible’. Another participant, Wilhelm Stuckart, who had helped to draw up the 1935 Nuremberg Laws, turning Jews into second class citizens and outcasts, proposed ‘compulsory sterilization’ of all ‘non-Aryans’ and the forcible dissolution of all ‘mixed’ marriages between Jews and non-Jews. But it was the work of the gas vans at Chelmno which was to be the model; since the second week of December more than a thousand Jews a day, and many Gypsies, had been taken from their homes and villages in western Poland, packed into the vans and killed during the drive from Chelmno church to the nearby wood. In the months following the Wannsee Conference, similar gassing vans, and gas chambers using diesel fumes, were to be set up at three further camps—Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka. Although remote, each camp was on a railway line; it was to be by rail that almost all the deportees were brought and killed. Only a handful, needed for menial work in the camps, were kept alive. There was no ‘selection’ of able-bodied men and women who might work in factories or farms; all who arrived—men and boys, women and girls, children, the old, the sick and the able-bodied—were murdered.

Death by gassing and by systematic killing was the ‘Final’, as opposed to any other, ‘Solution’, whether emigration or forced labour, or death by mass shooting. To ensure that the Final Solution worked smoothly, that the deportations were orderly and systematic, and that adequate deceptions worked throughout, Heydrich chose a senior officer, Adolf Eichmann, to carry out the Wannsee decisions. When the conference was over, Eichmann later recalled, ‘we all sat together like comrades. Not to talk shop, but to rest after long hours of effort’.

It was on January 20, the day of the Wannsee Conference, that a young Jew, Jakub Grojanowski, having escaped from the labour gang at Chelmno which was being forced to bury the bodies when they were thrown out of the gas vans, reached the nearby village of Grabow. Seeking out the local Rabbi, Grojanowski told him: ‘Rabbi, don’t think I’m crazed and have lost my reason. I am a Jew from the nether world. They are killing the whole nation of Israel. I myself have buried a whole town of Jews, my parents, brothers, and the entire family.’

***

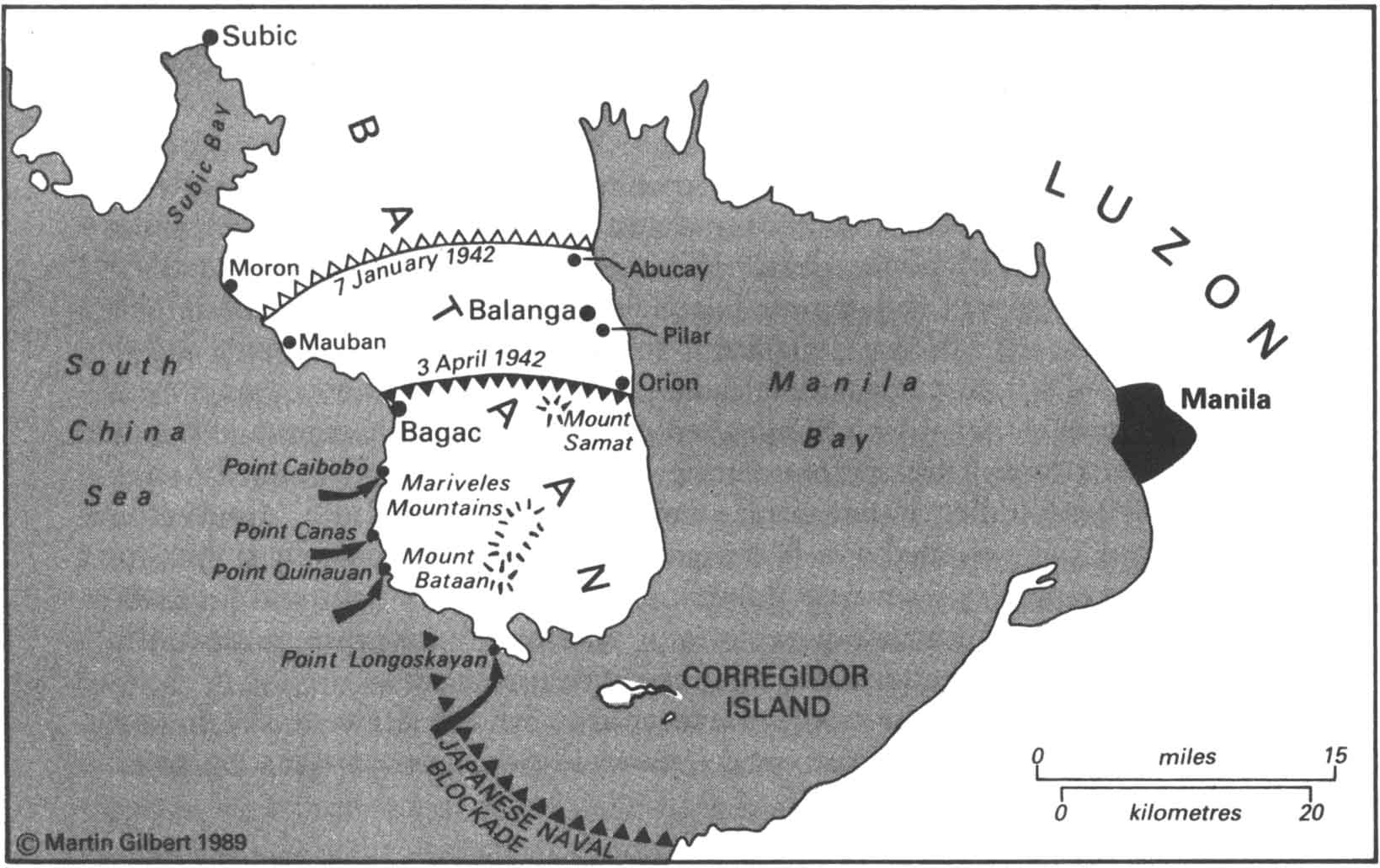

For the Western Allies, the news from all the war fronts was grim at the start of the third week of January. At Singapore, five British Hurricanes were shot down on January 21 by the Japanese Zero naval fighter aircraft. In North Africa, Rommel took the offensive on January 21, driving the British back across the desert halfway from Benghazi to Tobruk. ‘Our opponents are getting out as though they’d been stung,’ Rommel wrote to his wife on the following day. In the Philippines, MacArthur now ordered a withdrawal down the Bataan Peninsula, from the Mauban—Abucay line to behind the Pilar—Bagac road. That same night, however, the Japanese launched a series of amphibious landings south of Bagac. In Malaya, Japanese bombers struck at Singapore, causing heavy loss of life and considerable damage. Australian troops, trapped by a Japanese roadblock at Parit Sulong, tried to break through swamp and jungle to reach the British lines. Before setting off, they left their wounded at the roadside ‘lying huddled round trees, smoking calmly, unafraid’. Captured by the Japanese, the wounded men were taken to a nearby hut, where they were bayoneted to death, or shot. At Rabaul, in New Guinea, six thousand Japanese troops attacked an Australian garrison of a thousand; once again, most of the Australians were killed after they had been taken prisoner.

On January 23, Japanese troops prepared to land at Kieta on the Solomon Islands, at Balikpapan in Borneo, and at Kendari in the Celebes; a vast geographic span.

***

In German-occupied Europe, a pattern of war and resistance was emerging. On January 23, at Novi Sad on the Danube, Hungarian soldiers drove 550 Jews and 292 Serbs on to the ice of the river, which the soldiers then shelled until the ice broke up and the Jews and Serbs were drowned. That day, in Vilna, a group of young Jews met to set up a sabotage group against German military installations in the region. Asked one of them: ‘Where can we get the first pistol?’ By morning, another of the group later recalled, ‘We tenderly fondled the sanctified steel of our first pistol’.

Hitler’s plan did not envisage Jewish resistance or survival. On January 23, three days after the Wannsee Conference had given administrative backing to the Final Solution, Hitler told his entourage, in Himmler’s presence: ‘One must act radically. When one pulls out a tooth, one does it with a single tug, and the pain quickly goes away. The Jew must clear out of Europe.’ If the Jews were to ‘break their pipes’ on the journey, Hitler commented, ‘I can’t do anything about it. But, if they refuse to go voluntarily, I see no other solution but extermination’.

Lest his listeners were shocked by the word ‘extermination’, Hitler added, in words which could brook no misunderstanding: ‘Why should I look at a Jew through other eyes than if he were a prisoner-of-war?’

The Russian soldier knew that, for him, captivity would mean death. He was also aware of the daily murder of Soviet civilians in all the occupied regions. He fought with tenacity to drive the invader back, and to avoid capture. On January 23 Kholm was retaken from the Germans, and Rzhev all but encircled. Further south, Russian troops were poised to break through the German defences near Izyum, in an attempt to isolate the German troops in Kharkov by a southward thrust.

The Bataan Peninsula, January–May 1942

***

In Borneo, the Japanese invasion forces, about to land at Balikpapan, suddenly found their troop transports under sustained attack by four American destroyers and a group of submarines. Four of the sixteen Japanese transports were sunk, for no loss. It was America’s first naval victory, but it could not halt the occupation of Balikpapan. That same day, January 24, Japanese troops already on northern Bataan, in the Philippines, landed at Point Longoskayan, south of the whole American defence line. To Washington, General MacArthur signalled that ‘all manoeuvring possibilities’ were now over, and he added: ‘I intend to fight it out to complete destruction.’ For the soldiers, such heroic words masked a fearful prospect, one which they encapsulated in the pithy style of fighting men:

‘We’re the battling bastards of Bataan:

No mama, no papa, no Uncle Sam,

No aunts, no uncles, no nephews, no nieces,

No rifles, no planes, or artillery pieces,

And nobody gives a damn.’

On January 25, American and Filipino troops continued their southward retirement, reaching their objective, the Pilar—Bagac road, on the following day. But the Japanese would give them no respite, and within twenty four hours were closing up to continue the attack. Dense jungle made defensive preparations difficult, though Mount Samat, and the Mariveles mountains behind it, rising to 4,700 feet, provided good observation points. Time, however, was against the defenders, as the Japanese bombarded them from the air and, by skilful use of landing barges, by-passed the American defence line by sending troops from Subic Bay and Moron, to Point Caibobo, south of Bagac. The Americans were not, however, without resources or tenacity, and the landing force suffered considerable losses when attacked by an American PT—fast patrol—boat. Two more Japanese landings further south, at Point Canas and Point Quinauan, were successfully contained, so much so that the Japanese gave up their hopes of a rapid conquest of Bataan, and, between Bagac and Orion, had to pull back slightly to a more defensive line of their own, while at the same time calling for reinforcements from Manila, and asking Tokyo to send yet more troops from beyond the Philippines as a matter of urgency.

In New Guinea, on January 25, Japanese troops landed at Lae. Meanwhile, American troops had continued to cross the Atlantic for participation, in due course, in the war in Europe. On January 26, accompanied by a strong protest from the Irish Prime Minister, Eamon de Valera, the first American troops landed in Ulster. It was to be two and a half years before these troops reached Europe; meanwhile, Europe’s torment was unabated. On January 26, in German-occupied Yugoslavia, several hundred Jewish women and children were sent on foot, in the snow, from Ruma to Zemun. ‘The white death reaped,’ one eye witness later recalled. ‘Children were freezing in the arms of their mothers, who tried to warm them in their embrace. Mothers buried the frozen children quickly in the snow, hoping that others would bury them properly when spring arrived. The wife of Kurt Hilkovec lost her three children on the way. The youngest, born in Sabac, froze in her arms’. The destination of this march of horror was a concentration camp at Sajmiste; there, almost all the survivors of the march were killed in May.

On the second day of the Zemun death march, Hitler was again sounding off to his guests about the Jews. ‘The Jews must pack up, disappear from Europe,’ he insisted. ‘Let them go to Russia. Where the Jews are concerned, I’m devoid of all sense of pity. They’ll always be the ferment that moves people against one another’. Hitler added: ‘They’ll also have to clear out of Switzerland and Sweden. It’s where they’re to be found in small numbers that they’re most dangerous. Put five thousand Jews in Sweden—soon they’ll be holding all the posts there.’ It was ‘clearly’ not enough to expel Jews from Germany. ‘We cannot allow them to retain bases of withdrawal at our doors. We want to be out of danger of all kinds of infiltration.’ That same day, General Eisenhower criticized in his diary the American policy of ‘giving our stuff in driblets all over the world, with no theatre getting enough’, and he gave as his own view ‘that we must win in Europe’.

Europe knew no respite; on January 28, in the Crimean city of Feodosiya, thirty-six Russian partisans were captured and killed. In Dzhankoi, 141 ‘suspicious people’, as the Gestapo described them, were arrested; ‘seventy-six have already been shot after having been interrogated’, the report explained nine days later.

***

In the Far East, Japanese troops landed on January 28 on Russel Island, east of New Guinea. The threat to Australia was becoming a real one. In North Africa, Rommel’s forces occupied Benghazi on January 29. The threat to Egypt had been renewed. But the ebb and flow of war was evident with every day; on January 29, on Bataan, American and Filipino troops succeeded in destroying the Japanese bridgehead on Point Longoskayan. On the Eastern Front, Russian forces inflicted heavy losses on the Germans south-west of Kaluga, retaking Sukhinichi. That same day, Britain and the Soviet Union signed a Treaty of Alliance with Iran; British and Russian troops would remain in Iran until six months after the end of the war. The ‘Persian corridor’, under Anglo-Soviet control, would become the principal route for war supplies from the West to Russia. For his part, the Shah of Iran undertook ‘not to adopt in his relations with foreign countries an attitude which is inconsistent with the alliance’.

***

On January 30 Hitler celebrated the ninth anniversary of his coming to power in Germany. Speaking to a vast and enthusiastic crowd in the Sports Palace in Berlin, he declared: ‘The war will not end as the Jews imagine it will, namely with the uprooting of the Aryans, but the result of this war will be the complete annihilation of the Jews.’ The hour would come, Hitler warned, ‘when the most evil universal enemy of all time will be finished, at least for a thousand years’. On the following day, Operation Situation Report USSR No. 170, sent from Berlin to more than sixty recipients, noted under the heading ‘Top Secret’ that in the previous six days, in the Crimea, ‘3,601 people were shot: 3,286 of these were Jews, 152 Communists and NKVD agents, 84 partisans, and 79 looters, saboteurs, and asocial elements. In all, to date 85,201.’

The statistics of death in the Second World War will never be complete. That same January 31, it was noted in Leningrad that more than 200,000 citizens had died of starvation and cold since the siege had begun nearly five months earlier.

For Leningrad, an avenue of hope now lay, across the ice of Lake Ladoga. Although during snow storms the journey could take seven hours, the journey time had been reduced to two and a half hours, even two; in the three months after January 22, when the shorter route first became possible, a total of 554,186 people were taken out to safety, among them 35,713 wounded soldiers. Among the Axis troops facing the Russians in Leningrad that winter were nearly a thousand Dutchmen, members of a Dutch Volunteer Legion. They were to serve on the front for more than a year, complete with their own Dutch Red Cross until, and a special propaganda company of fifty photographers and press cameramen.

Behind the lines, on the Eastern Front, Soviet partisans were active in disrupting German movement; on January 31 a German report noted that in the Yelnya—Dorogobuzh area ‘the partisan movement is gaining the upper hand’. Not only were ambushes and attacks a daily occurrence, but a partisan field hospital was said to have been set up near Yelnya.

***

On the last day of January 1942, the last British troops withdrew from the Malayan mainland to the island of Singapore, where British, Australian, Indian, Canadian and Malayan troops now awaited the Japanese assault. Shelling began at once. On Bataan, as at Singapore, a siege had begun in which superior Japanese numbers and firepower were ill omens. But 2,800 miles east of Bataan, in mid-Pacific, American aircraft carriers engaged in their first offensive action of the war, launching air strikes on the Japanese Marshall Island bases of Kwajalein, Wotje and Maloelap. During the action, the carrier Enterprise was damaged, but not sunk, by a Japanese torpedo bomber.

On Dutch Timor, as Australian troops surrendered, a group of several hundred Australian commandos took to the jungle, where they continued to harass the Japanese for eleven months, before being taken off to safety; in those eleven months, they killed 1,500 Japanese, for the loss of 40 of their own number. It was those Australians who surrendered whose fate was terrible; ten Australian soldiers, captured on February 1 at Sowacoad, on Amboina island, were bayoneted to death. This was done, the Japanese commander explained, because the prisoners ‘were likely to become a drag’ upon the movement of the Japanese forces in their march to join the other Japanese troops on the island. But elsewhere on the island, equal savagery was enacted; when the principal port of Amboina was overrun, and its small garrison of 809 Australian defenders surrendered, 426 of them were bayoneted to death by their Japanese captors, or died of torture or starvation as prisoners-of-war. On February 4, a further thirty Australian prisoners-of-war were taken to Sowacoad and bayoneted to death, or decapitated. ‘They were taken one by one to the spot where they were to die,’ their executioner, Lieutenant Nakagawa, later recalled, ‘and made to kneel down with a bandage over their eyes.’ Nakagawa’s men then ‘stepped out of the ranks, one by one as his turn came, to behead a prisoner-of-war with a sword or stab him through the breast with a bayonet’.

On February 5, a further thirty Australian and Dutch prisoners-of-war were similarly killed. Near Rabaul, a hundred and fifty Australian prisoners-of-war had been massacred on the previous day. Asia was competing with Europe in terror; on February 1, in German-occupied Russia, the last surviving thirty-eight Jews and Gypsies in Loknya had been murdered, followed three days later by all the hundred Jews in Rakov, near Minsk.

***

On February 1, British Intelligence suffered its most serious setback of the war. The German Submarine Command, as part of an internal security drive, altered its Enigma machine in such a way that it was to prove unreadable for the rest of the year. Suddenly, the bright light of knowledge which shone on German submarine movements in the Atlantic and Mediterranean was extinguished. At the same time, British cyphers carrying most of the Allied communications about the North Atlantic convoys were broken by German Naval Intelligence. In the signals war, the naval advantage swung suddenly and decisively away from Britain. But two more of Germany’s Enigma cyphers were broken that February, ‘GGG’, the German Secret Service messages between Berlin and stations in the Gibraltar area, and ‘Orange II’, the messages between Berlin and the SS formations fighting as an integral part of the German Army on the Eastern Front.

For those SS combat troops, as for all German units facing the Russians, or behind the Russian lines, February 1942 saw a considerable increase in partisan activity. ‘Since we have no continuous forward line,’ a German Army report noted on February 1, ‘traffic of every kind from the Soviet side and back again is possible, and extensive use is being made of such crossings. New partisan bands have infiltrated. Russian parachutists are being dropped and are taking over leadership.’ In February 1942 the Second Leningrad Partisan Brigade received by parachute drop a Boston printing press, on which it was able to print its own paper, the People’s Avenger.

Vengeance itself had become an almost daily event in the East. ‘We prepared an ambush in the village of Bereski,’ the eighteen-year-old Vyacheslav Balakin noted in his partisan diary on February 4. ‘We shot down three Germans in cold blood. I wounded one. One was captured alive. I captured a cigarette lighter, a gold ring, a fountain pen, two pipes, tobacco, a comb. Morale is “Gut”.’

Five days later, Balakin’s partisan group ‘shot a traitor’. Later that day, Balakin wrote: ‘I went to do the same to his wife. We are sorry that she leaves three children behind. But war is war!!! Towards traitors, any humane consideration is misplaced.’ In the evening, a German ‘punitive expedition’ reached Balakin’s region. His group escaped, but two Russian peasants were killed.

Near Kiev, Operational Situation Report USSR no. 164 noted on February 4, sixty Russians were shot, several of them partisans. Five days later, the Germans launched Operation Malaria against Soviet partisans operating in the Osipovichi area. In the rear areas, German units which had to combat partisan activity had their own wry jingle:

‘Russians in front,

Russians behind,

And in between

There’s shooting.’

Another region of increasing partisan activity against the Germans was Yugoslavia; on February 5 a British mission, Operation Disclaim, was parachuted near Sarajevo to link up with recently dislodged partisan forces. But the balance of massacre remained with the Germans; in the southern Russian city of Dnepropetrovsk, for example, in the four weeks up to February 6, an Operational Situation Report USSR, compiled in Berlin, noted that ‘17 habitual criminals, 103 Communist officials, 16 partisans and about 350 Jews were shot by order of the Summary Court’. In addition, four hundred inmates of the Igren mental hospital were ‘disposed of’: a total of 1,206 people.

From Lithuania, the head of the Gestapo, SS Colonel Karl Jaeger, reported to Berlin that, in the previous seven months, his special units had killed 138,272 Jews, of whom 34,464 were children. They had also killed, according to Jaeger’s precise statistics, 1,064 Russian Communists, 56 Soviet Partisans, 44 Poles, 28 Russian prisoners-of-war, five Gypsies and one Armenian. Murders took place every day; driven on February 6 from their homes in the Polish town of Sierpc, five hundred Jews were shot down and killed during a march to the nearby town of Mlawa. That February, in Warsaw, 4,618 Jews died of starvation. From the village of Sompolno, a thousand Jews were taken to Chelmno and gassed.

These gassings were seen by certain fanatical Nazis as being able to serve a ‘scientific’ purpose. On February 9 the German anthropologist and surgeon, Auguste Hirt, head of the Anatomy Institute which had just been set up at the University of Strasbourg, wrote to Heinrich Himmler: ‘By procuring the skulls of the Jewish—Bolshevist Commissars, who represent the prototype of the repulsive but characteristic subhuman, one has the chance to obtain palpable scientific data. The best practical method is to turn over alive all such individuals. Following induced death of the Jew, the head, which should not be damaged, should be separated from the body and sent in a hermetically sealed tin can filled with preservative fluid’.

Himmler gave Hirt the authority he needed. Henceforth, Hirt used the skulls of more than a hundred murdered Jews to pursue his medical—scientific work. More than a year later, Adolf Eichmann was informed that a total of 115 people had been killed for their skeletons: seventy-nine Jews, thirty Jewesses, four Russians from Central Asia and two Poles.

***

In an attempt to centralize and accelerate the German war effort, on February 6 the Minister for Armaments and War Production, Fritz Todt, took the chair in Berlin at the first meeting of a committee to co-ordinate all ministries involved in armaments design, manufacture and distribution. On the following day he flew to Rastenburg, to tell Hitler what had been decided; a fifty-five per cent increase in German arms production. On February 8 Todt left Rastenburg to fly back to Berlin. His plane crashed on take-off, and he was killed. Hitler was much shaken by the death of the man who had served him, and Germany, so well; whose Todt Organization utilized hundreds of thousands of slave labourers. That week, Todt was succeeded by Hitler’s architect, the thirty-six-year-old Albert Speer. He too showed no scruples in exploiting the labour of Frenchmen, Dutchmen, Danes, Belgians, Poles and a dozen other captive peoples. In Todt’s memory, the battery of naval guns, inaugurated by Grand Admirals Raeder and Dönitz on the Channel coast at Haringzelles on February 10, and protected by massive concrete towers, was given the name ‘Battery Todt’.

In North Africa, the German army had continued to drive the British back towards Egypt: ‘We have got Cyrenaica back’, Rommel wrote to his wife on February 4. ‘It went like greased lightning.’ In the Far East, the Japanese struck at a troop convoy bringing Indian soldiers to Singapore; the slowest ship in the convoy, the Empress of Asia, was sunk. Most of the troops on board were rescued, but nearly all their weapons and equipment lost. That day, Japanese heavy guns opened fire on Singapore’s defences. The city, declared General Percival on February 7, would resist to the last man.

On February 8, five thousand Japanese troops crossed the Johore Straits from Malaya, to land on Singapore Island. For seven days the British defenders fought against a numerically superior, and better armed, enemy. Leaflets dropped over the city on February 11, calling for its surrender, were studiously ignored. As the garrison in Singapore continued its stubborn defence, the Germans carried out Operation Cerebus, sending the battle cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, from the port of Brest through the English Channel into the North Sea. The British public was cast down by this spirited ‘Channel Dash’, as it became known, and by the loss of ten of the old-fashioned naval torpedo aircraft sent to intercept the warships. But in the inner circles of war policy there was immediate relief when the Enigma messages revealed that during the dash both Gneisenau and Scharnhorst had been damaged by mines laid with foreknowledge of the ships’ route. This foreknowlege had itself been gained from Enigma. ‘This will keep them out of mischief for at least six months,’ Churchill told Roosevelt, ‘during which both our Navies will receive important accessions of strength.’

Not Allied strength however, but weakness, now made up the daily diet of war news. On February 13 the Japanese destroyed Singapore’s principal defence, its massive fifteen-inch coastal guns and, in south-eastern Borneo, occupied the port of Bandjarmasin. On February 14, Japanese parachutists landed at Palembang in Sumatra. On the following day, Singapore surrendered; 32,000 Indian, 16,000 British and 14,000 Australian soldiers being taken prisoner. More than half of them were to die while prisoners-of-war.

The fall of Singapore—the ‘Gibraltar of the East’—was a serious blow to Britain’s ability to resist Japan, and also a severe blow to British morale. ‘Here is the moment’, Churchill told the British people in a broadcast on February 15, ‘to display the calm and poise, combined with grim determination, which not so long ago brought us out of the very jaws of death.’ The ‘only real danger’, Churchill warned, would be ‘a weakening in our purpose and therefore in our unity—that is the mortal crime’. Whoever was guilty of such a crime, or of bringing it about in others, ‘it were better for him that a millstone were hanged about his neck and he were cast into the sea’.

Churchill urged his listeners not to despair. ‘We must remember’, he said, ‘that we are no longer alone. We are in the midst of a great company. Three-quarters of the human race are now moving with us. The whole future of mankind may depend upon our action and upon our conduct.’ So far, Churchill added, ‘we have not failed. We shall not fail now. Let us move forward steadfastly together into the storm and through the storm.’