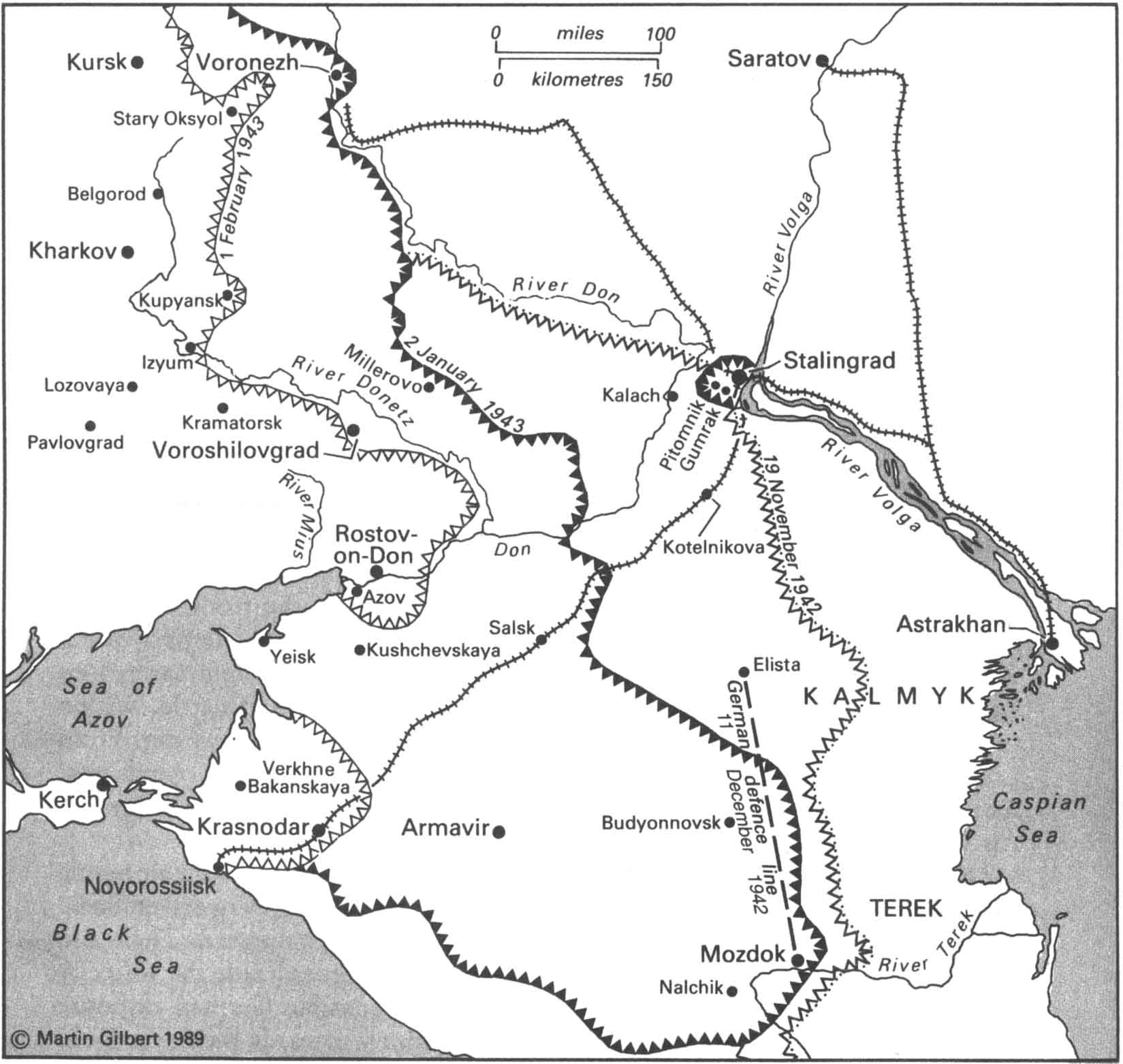

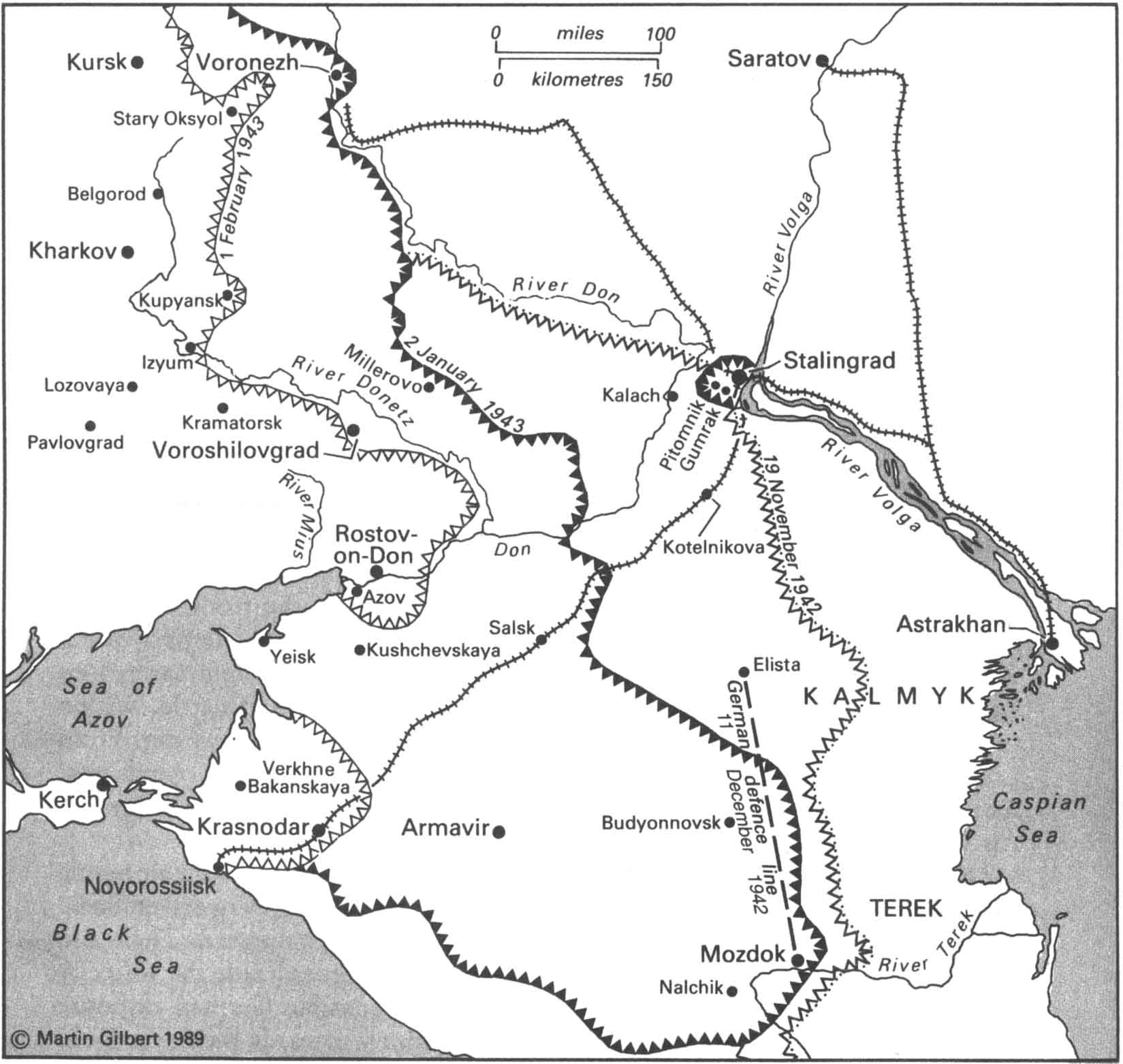

The Soviet reconquest of the Caucasus and the Don, winter 1942–1943

On 19 November 1942 the Red Army launched a counter-offensive north of Stalingrad, preceded by one of the most intense artillery bombardments of the war, when, to the call sign ‘Siren’, more than 3,500 guns and mortars opened fire on a fourteen mile front, followed, on one sector of the front, by Soviet martial music blared out by the ninety-strong divisional band. As part of the Russian plan, a particularly fierce assault was made on the Roumanian troops holding part of the line; troops with no previous experience of battle. Within twenty-four hours, 65,000 Roumanian soldiers had been taken prisoner. From London, at Churchill’s personal insistence, the Russians were sent operational Intelligence, overheard by the British through Enigma, about German Army and Air Force intentions.

Not only Roumanian, but also Hungarian and Italian forces, fought alongside the Germans during the Russian assault on November 19. All were driven back. Then, on November 20, the Russians attacked south of Stalingrad. Their aim was a bold and dramatic one, to encircle the German forces inside the very city which the Germans themselves were encircling. A sensible German response would have been to break off the siege and withdraw towards the River Don. This proposal was made by General von Paulus on November 21. But Hitler would not allow any withdrawal whatsoever, issuing an order from Berchtesgaden that same day that von Paulus’s Sixth Army must stand firm ‘despite the danger of its temporary encirclement’.

On November 22 the Russian pincer closed south of Kalach, on the Don, trapping well over a quarter of a million men inside a circle that was to be drawn tighter every day. For the defenders of Stalingrad, so nearly driven into the Volga, the Soviet winter offensive brought the first relief for two months; the city, devastated and almost entirely overrun, had not succumbed, and would not now be lost. ‘Hold on!’, Hitler broadcast that day to the Sixth Army; but von Paulus saw no hope in holding on, and that same night asked for Hitler’s permission to break out of the trap. Hitler did not reply; he was already in his train on his way from Berchtesgaden to Leipzig, from where he flew to Rastenburg. There, he assumed ‘personal command’ of the German Army, and, on November 24, answered Paulus’s request to break out of the encirclement with an emphatic refusal. Stalingrad must not be abandoned.

The Soviet reconquest of the Caucasus and the Don, winter 1942–1943

***

In the Mediterranean, the Allies had begun to experience, for the first time, the sweet taste of success; on November 20 a convoy of merchant ships, Operation Stone Age, reached Malta from Egypt under the protective umbrella of British aircraft. The siege of Malta was over. As the ships entered Valetta, the islanders lined every vantage point to cheer, while naval bands played in the ships with welcoming music. In the Western Desert, following the loss of Benghazi on November 20, Rommel fell back to El Agheila, more than five hundred miles from the Egyptian frontier across which he had so recently stood in triumph. In Tunisia, British, Free French and American troops had taken control of the western half of the country, and on November 25 American troops, raiding the airport at Djedeida, destroyed thirty German and Italian aircraft on the ground. But the Allies were not to occupy Tunis, which they had hoped to reach within a month, until the following May. Thus Hitler was able to maintain his formidable pressure on Allied shipping, still forced to use the long and costly Cape of Good Hope route.

In Toulon harbour, fifty-eight French warships now awaited the arrival of the German forces sent to occupy Vichy France. For the Germans, this was a major prize; the seizure of the ships had even been given a code name, Operation Lila. But on the morning of November 27, as SS troops began to take over the naval base, the commander of the French Fleet, Admiral Jean de Laborde, gave orders for the ships to be scuttled. His orders were obeyed, and two battleships, two battle-cruisers, four heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, an aircraft transport, thirty destroyers and sixteen submarines were sunk. Three more submarines managed to put to sea and, avoiding the Germans, to join the Allied forces at Algiers. A fourth, also escaping, was interned by the Germans at Carthage.

The scuttling of the French Fleet at Toulon fulfilled the promise made to the British by Admiral Darlan in June 1940, and partly broken at Oran that same July, that the French Navy would never be allowed to fall into German hands. On November 28, at Rastenburg, Rommel urged upon Hitler the need to abandon the African theatre of war altogether as ‘no improvement in the shipping situation could now be expected’. If the Army remained in North Africa, Rommel insisted, ‘it would be destroyed’. Hitler refused to accept Rommel’s advice, or even to discuss it. It was a ‘political necessity’, he said, to hold a major bridgehead in North Africa.

Hitler now proposed, not to allow von Paulus to break out of the Stalingrad trap, but to break into the trap from outside. This was Operation Winter Storm. Its planning coincided with yet another Russian counter-attack, this time in the Terek region of the Caucasus. Soviet partisans were also active in this region, as in the area north of Novorossiisk where, on November 29, the Germans murdered 107 villagers at Verkhne-Bakanskaya for ‘direct or indirect’ connections with the partisans. The partisans themselves, however, escaped. Much further behind the German lines, to the west of the River Dnieper, the end of November saw the establishment of two partisan bands, one led by Sidor Kovpak, the other by Alexander Saburov, who, uniting their forces, and operating from the region of the Pripet Marshes, began to cause havoc to the German lines of communication passing through the Ukraine. The Germans reacted, however, with frequent and savage sweeps, one of which, Operation Munich II, was launched that December against Soviet partisans in the Radoshkovichi region of White Russia, just north of the area of Kovpak’s and Saburov’s hideaway.

***

In the Pacific, throughout the last ten days of November, the Japanese tried to re-inforce their isolated and besieged garrison on the island of Guadalcanal. In a series of violent clashes with American warships, there were moments when it looked as if the Japanese attempt would succeed. On November 22, the American warship Juneau was sunk, and more than six hundred men were drowned. A hundred more clung to the wreckage. All but ten of them were eaten by sharks, or went mad as a result of the privation and drowned.

The Japanese tried once more, on November 30, to reinforce their now struggling garrison on Guadalcanal. Intercepted by the Americans during a night battle off Tassafaronga, the Japanese transports were forced to turn back. But the battle itself was a blow to the Americans, seriously damaging three heavy cruisers, Pensacola, New Orleans and Minneapolis, and sinking a fourth, the Northampton, fifty-eight crew members of which were killed. In New Guinea, the Australians reached the northern shore, recapturing Buna, but the Japanese, withdrawing to Buna Mission, continued their resistance, nor could the Americans dislodge them from the Soputa—Sanananda track. Thus 15,000 Australians and 15,000 Americans, despite complete mastery of the air, and virtual mastery of the sea, found themselves in vicious combat with less than half of their number of Japanese.

Far from the swamps and jungles of New Guinea, December 2 saw a decisive moment of the war take place, in strictest secrecy, in a rackets court on the campus of the University of Chicago. Here, at ten o’clock that morning, the Italian emigré scientist Enrico Fermi gave the order for an experiment to begin which, by mid-afternoon, had produced the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. All was now set to find and process the necessary uranium for the manufacture of an atomic bomb.

***

On December 4, in Brussels, members of the Belgian resistance shot dead a Belgian member of the ‘Germanic SS’, a unit created by the Germans from fascist-inclined Belgians. That same day, in Warsaw, a group of Christian Poles, led by two women, Zofia Kossak and Wanda Filipowicz, set up a Council for the Assistance of the Jews. Their task was one filled with danger; only two days later, at Stary Ciepielow, the SS locked thirteen Poles—men, women and children—into a cottage, and ten more into a barn, and then burned them alive on suspicion of harbouring Jews. That same day, in the Parczew forest, the Germans launched a four-day manhunt against more than a thousand Jews in hiding. ‘We fled round and round in terror,’ one of those in hiding, Arieh Koren, later recalled, as Germans with machine guns, four small cannon and armoured vehicles penetrated the forest. ‘We thought we had run twenty kilometres, but actually we circled an area of half a kilometre.’

In the village of Bialka, near Parczew, Jews found refuge with the villagers. But on the second day of the hunt, December 7, the Germans entered the village and shot ninety-six Poles for helping Jews. Three days later, in the village of Wola Przybyslawska, seven Poles were executed by the Germans for hiding Jews.

***

Over Italy, British bombers had continued to strike at naval installations. In a raid on Naples on December 4, a light cruiser, Muzio Attendolo, was sunk, and 159 Italians killed. That day, however, in the Tunisian battle which these air strikes were intended to help, the Germans counter-attacked, destroying twenty-five British tanks and taking four hundred prisoners. Two days later, on December 6, German armoured forces broke through the American positions at El Guettar.

The Italians, Germany’s ally in the Tunisian battle, sought unusual means to advance the Axis cause. On the night of December 7 three Italian manned-torpedoes—known as ‘Chariots’—tried to enter Gibraltar harbour. Of the six men who made up their crews, three were killed in action, two taken prisoner, and one returned to the support ship. No damage was done to Gibraltar harbour or to the ships in it. Four days later, however, another three Chariots entered Algiers harbour, sinking four Allied supply ships.

In the Far East, the Japanese made two further unsuccessful attempts to reinforce their troops both on Guadalcanal and New Guinea. Both attempts were repulsed on December 8. On the following day, the Australians overcame the last Japanese resistance in the Gona area. When the final battle ended, more than five hundred Japanese dead lay on the battlefield; once more, they had refused to surrender.

On the Russian front, German efforts to regain the initiative around Stalingrad, on the Don, and in the Caucasus, came to nothing; the German Air Force Enigma messages made it clear that there had been such heavy losses in transport aircraft sent to the Tunisian front that there were no longer enough to satisfy the needs of the Stalingrad defenders. Reading these Enigma messages in London, Churchill asked his Chief of Intelligence, Sir Stuart Menzies: ‘Is any of this being sent to Joe?’ It was; Stalin was kept well informed by London of deficiencies and setbacks in the German reinforcements being sent to Stalingrad.

In the Caucasus, on December 11, the Germans withdrew to the Mozdok–Elista line, accepting that their bid to reach the Caspian Sea had finally failed. On the following day, in the Kotelnikovo area, less than a hundred miles south-west of Stalingrad, the Germans launched Operation Winter Storm, hoping to break through to the trapped Sixth Army. For two days, it seemed as if the link-up might be made, but then Russian reinforcements hurried forward to check the German thrust, while other Russian troops attacked along the River Don north-west of Stalingrad, wiping out the whole of the Italian Eighth Army, and part of the Roumanian Third Army. The Germans, rushing reinforcements to this weakened sector of the front, were forced to take troops away from Winter Storm, itself under threat. The Stalingrad trap remained closed.

Far from the battleheads of the Volga and the Don, in the quiet waters of the River Gironde, December 12 saw the culmination of a daring commando raid, when twelve British commandos, brought to the river estuary by submarine, went upriver by canoe and, during five consecutive days and nights in enemy waters, placed limpet mines on eight ships. All eight ships were blown up, to Hitler’s intense anger, and Britain’s delight.

There was an even greater British triumph on the following day, although it had to be kept secret from all but a dozen or so of those at the centre of war direction. This was the breaking of the German U-boat Enigma key, known to the British as ‘Shark’, which had been unreadable for more than a year. In November 1942 the Allies had lost 721,700 tons of merchant shipping to German submarine attack, the highest figure for any month of the war. The success of mid-December came none too soon. Whereas, in November, eighty-three Allied ships had been torpedoed, in December the figure fell to forty-four and in January 1943 to thirty-three. It was a triumph of cryptography, and also a testimony to the bravery of the two British seamen, Tony Fasson and Colin Grazier, who, at the end of October, had lost their lives while retrieving an Enigma machine and highly secret signal documents off the Nile Delta.

***

In Tunisia, the Germans were confronted by one aspect of Italian rule which they did not like. ‘The Italians are extremely lax in their treatment of Jews,’ Goebbels wrote in his diary on December 13, and he went on to explain: ‘They protect Italian Jews both in Tunis and in occupied France and won’t permit their being drafted for work or compelled to wear the Star of David.’ Nor would the Italians agree to deport to Auschwitz either the Jews in Italian occupied France and Croatia, or those in Italy itself. The Germans could only deport Jews from those countries where the local police force was prepared to co-operate at least in the round-ups and initial incarceration in holding camps; thus, from Westerbork camp in Holland, three trains, with a total of 2,500 Jews on board, were sent eastward to Auschwitz that December. From German-occupied Poland, however, the deportations were almost over. Nearly three million Polish Jews had been murdered in the previous twelve months at Chelmno, Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka.

During December, the Germans began to ‘liquidate’ the various labour camps which had been set up at the time of the deportations, killing in each camp the few hundred Jews who had been kept alive to service a factory or a farm. At a camp near Kruszyna, 557 Jews were killed on December 17; a week later the 218 slave labourers at Minsk Mazowiecki were done to death and, a week after that, the four hundred at Karczew. Nor was it the Jews alone who continued to be rounded up and deported; on December 16 Himmler issued an order whereby all individuals of mixed Gypsy blood should be sent to Auschwitz. The only exceptions to this order were Gypsies who agreed to be sterilized. By a cruel coincidence, December 16 was also the day on which, at Auschwitz, ninety castration experiments were made on Polish, non-Jewish, prisoners in the camp, who were subjected to experiments so painful that many of them, as one eye-witness has recalled, ‘often crawled on the floor in their pain’. After a long period of suffering, those on whom the experiments were made were sent to the gas chamber.

December 16 also saw the publication of an order issued by the German Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal Keitel, at Hitler’s instigation, intended to curb partisan activity both in Russia and in Yugoslavia. ‘If the fight against the partisans in the East, as well as in the Balkans, is not waged with the most brutal means,’ the order read, ‘we shall shortly reach the point where the available forces are insufficient to control this area. It is therefore not only justified, but it is the duty of the troops to use all means without restriction, even against women and children, so long as it ensures success.’ Any ‘consideration’ for the partisans, the order ended, ‘is a crime against the German people’.

On December 17, the three principal Allies—Britain, the Soviet Union and the United States—issued a declaration in each of their capitals, announcing that ‘the German authorities, not content with denying to persons of Jewish race in all the territories over which their barbarous rule has been extended the most elementary human rights, are now carrying into effect Hitler’s oft-repeated intention to exterminate the Jewish people in Europe’. From all the occupied countries, the Allied declaration continued, ‘Jews are being transported, in conditions of appalling horror and brutality, to Eastern Europe. In Poland, which has been made the principal Nazi slaughterhouse, the ghettos established by the German invaders are being systematically emptied of all Jews except a few highly skilled workers required for war industries. None of these taken away are ever heard of again. The able-bodied are slowly worked to death in labour camps. The infirm are left to die of exposure and starvation or are deliberately massacred in mass executions. The number of victims of these bloody cruelties is reckoned in many hundreds of thousands of entirely innocent men, women and children’.

The Allied declaration went on to state that the British, Soviet and American governments, and also General de Gaulle’s French National Committee, ‘condemn in the strongest possible terms this bestial policy of cold-blooded extermination’.

***

On the field of battle, the Allies continued everywhere in the ascendant, except in Tunisia, where they were bogged down by wintry conditions and unexpected opposition. On Guadalcanal and in New Guinea, the Japanese were being pushed steadily back. Around Stalingrad, the Russians continued to widen the gap between the encircled German armies and those seeking to break through to them. In Libya, the German and Italian forces were retreating westward. ‘We’re in heavy fighting again’, Rommel wrote to his wife on December 18, ‘with little hope of success, for we’re short of everything.’ Petrol in particular was short, he added, ‘and without petrol there’s nothing to be done’.

On December 19, German forces which had come to within forty miles of Stalingrad made yet another attempt to link up with the trapped troops under von Paulus. But, despite a massive effort, they were checked by the Russians, and on the following day, at Rastenburg, even Hitler accepted that von Paulus could not be reached. Nor, it seemed, could he now break out; his tanks had fuel for less than fifteen miles.

In the Caucasus, the Russians had succeeded by late December in infiltrating as many as eight hundred partisans behind the German lines near Budyonnovsk. These partisans were active in mining railroads and bridges, destroying fuel oil depots, seizing control of small settlements, recruiting new partisans and killing collaborators. ‘We have destroyed about fifty Germans and Cossacks,’ one partisan noted in his diary on December 21. When, six days later, Cossack and Kalmyk units, working for the Germans, raided the partisan base, the partisans had already moved elsewhere.

On December 22, an act of defiance was carried out in the very centre of German-occupied Europe, in the Polish city of Cracow, where six members of the Jewish Fighting Organization, which had been set up in Poland five months earlier, attacked a café frequented by the SS and the Gestapo. Armed only with pistols, their attack was bound to fail. The aim of the attack, one of them later wrote, was ‘to save what could be saved, at least of honour’. Their leader, Adolf Liebeskind, was killed by German machine-gun fire. ‘We are fighting’, he had remarked a few weeks before the attack, ‘for three lines in the history books.’

Outside Stalingrad, a German armoured column managed on December 23 to come to within thirty miles of the besieged Sixth Army. But with tank fuel for only a fifteen mile movement, von Paulus could no longer plan a breakout with any serious chance of success. Fuel oil was also the cause of Rommel’s failure that week to do anything but slowly withdraw to the west. On Christmas Eve, at his Headquarters Company’s Christmas Party, Rommel was given as a present a miniature petrol drum, containing, instead of petrol, a pound or two of captured British coffee. ‘Thus proper homage was paid’, Rommel noted, ‘to our most serious problem, even on that day.’

On Christmas Eve, on the Eastern Front, the besieged von Paulus learned ominous news. Because of a swift Russian advance against the German forces already driven south of the Don, towards Millerovo, the 6th Panzer Division was being taken away from the armoured units still seeking to break through to Stalingrad, and transferred to the Don. The only German success that day was a secret one, the successful test launching of the first flying bomb, a jet-propelled, pilotless aircraft, which flew a mile and a half at the test site at Peenemünde. At least a year’s more testing and developing would need to be done, as well as the building of suitable sites in north-western France, but at least a German secret weapon now existed, from which a great deal was hoped. As with the American atomic pile at Chicago, so with the German flying bomb at Peenemünde, the most fanciful ideas of pre-war science were being turned into reality, in order to meet the demands of total war.

As science made its slow, experimental progress in laboratory and testing ground, terror advanced with no delays or hesitations; on December 24, in the Parczew forest, the Germans launched a second manhunt. Several hundred Jews in hiding in a ‘family camp’ were seized and slaughtered. The survivors, unarmed, frightened, freezing and without food, were fortunate: they found a protector, the twenty-four-year-old Yekhiel Grynszpan, from a family of local horse-traders, who, that winter, built up a partisan unit of thirty to forty Jews, foraged for food, acquired arms from the local Polish peasants whom his family had known before the war, and, when German soldiers entered the forest, fought them off. Also on December 24, the day of the Parczew ‘sweep’, the Germans entered the Polish village of Bialowieza, and executed three hundred Poles for partisan activity. Today, a monument stands in silent testimony on the site of their mass grave.

***

In Tunisia, throughout December 24, the Allies battled in vain to break through the Axis defences. There was excitement throughout North Africa that day as news spread that Admiral Darlan had been assassinated by a French student in Algiers. ‘Darlan’s murder,’ Churchill later wrote, ‘however criminal, relieved the Allies of their embarrassment at working with him, and at the same time left them with all the advantages he had been able to bestow during the vital hours of the Allied landings.’ In Darlan’s place as High Commissioner and Commander-in-Chief of the French forces in Morocco and Algeria, the Allies appointed General Giraud.

On December 27, at Rastenburg, Hitler listened as General Zeitzler advised him that German forces should withdraw from the Caucasus. If not, Zeitzler warned, ‘you will have a second Stalingrad on your hands’. Hitler accepted this advice. Two days later, on December 29, the Russians retook Kotelnikovo, from which the Germans had begun their attempt to spring the Stalingrad trap. ‘Outwardly one has to be optimistic about the future in 1943,’ King George VI noted in his diary that day, ‘but inwardly I am depressed at the present prospect.’

As 1942 came to an end, the Axis powers were in retreat in Libya, on Guadalcanal and New Guinea, and at Stalingrad and in the Caucasus. Partisan activity, though savagely suppressed, was also proving more and more effective. Yet at the same time, as well as maintaining its position in Tunisia, the Axis were still in full control of vast expanses of territory, and of hundreds of millions of captive people throughout Europe and Asia.

In south-east Asia and the Pacific, the forces of Japan were installed over an enormous area, from the borders of India to the islands of Alaska. In Europe, the Germans were masters from the Pyrenees to the North Cape, and from Cape Finisterre to Cape Matapan. Tyranny, too, was uncurbed. On December 29, sixty-nine villagers in tiny Bialowola, in central Poland, had been driven into the school house and shot. But this massacre, terrible as it was, paled into insignificance when seen in the context of the death that December, at nearby Poniatowa, of a total of eighteen thousand Soviet prisoners-of-war; they had died of starvation—prisoners in a camp in which they had been denied all food. On December 31, at Rastenburg, Hitler was shown a report, signed by Himmler, giving a precise statistic of the number of ‘Jews executed’ for the four months August to November. The figure given was 363,211.

In the Arctic, Captain Robert Sherbrooke, in command of a British destroyer force, beat off a sustained German naval attack led by the battleship Lützow and the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper, on a Russia-bound Arctic convoy. During the action, Sherbrooke was hit in the face, losing the use of one eye, but continued to direct the defence to such good effect that not a single merchant ship was lost or damaged. For his defiance and courage, Sherbrooke was awarded the Victoria Cross.

That New Year’s Eve, British bombers dropped their bombs on Düsseldorf. They did so on a cloudy night, but with a new device, ‘Oboe’, a radio beam which enabled bombs to be dropped on target, or as near to target as possible, without anything of the towns being visible from the air. Science, no longer neutral, had come to the aid of deliberate destruction.