From Tunis to Sicily, May–July 1943

In the scientific air war, 26 May 1943 was a double landmark. In Washington, Roosevelt agreed to Churchill’s request that the Anglo-American exchange of information on the atomic bomb, suspended for more than a year because of mutual suspicions, should be resumed, and that henceforth the enterprise should be considered a joint one, ‘to which both countries would contribute their best endeavours’. That same day, at Peenemünde, on the Baltic coast, Albert Speer, again witnessing a series of demonstrations, agreed that work should go ahead on two different types of long range missile, the pilotless plane—later known as the V1, and the rocket bomb—the V2.

Both the Anglo-American and German secret weapons were still at the experimental stage. On May 27, however, the air war took another step forward along its existing path, when British Bomber Command instructed its planners and pilots to prepare for Operation Gomorrah, the total destruction of Hamburg by ‘sustained attack’. Meanwhile, during a British night raid on Wuppertal on May 29, in which the centre of the city was engulfed in a firestorm, a total of 2,450 German civilians were killed and 118,000 people left homeless.

On 28 May 1943 the American attempt to recapture Attu Island from the Japanese reached a bloody climax when the Japanese forces, reduced to a thousand men, launched a suicide attack on the Americans. First, a hundred Japanese were killed. Then, early on May 30, the survivors committed mass suicide with hand grenades, leaving the Americans in possession of the island, and with only twenty-eight wounded prisoners. On May 31, American troops combed the island in search of Japanese survivors. They found only corpses. In three weeks of fighting, 600 Americans, and 2,500 Japanese, had been killed.

The American victory on Attu Island came at a moment when, in German-occupied France, strenuous efforts were being made to bring together all the Resistance groups under a single leadership. It was to achieve this that Jean Moulin had been parachuted into France more than a year before. On May 27 he was finally successful. At a secret meeting in Paris, fourteen Resistance leaders, representing eight separate movements, agreed to accept the overall leadership of General de Gaulle. A month later, however, Jean Moulin was among a number of Resistance leaders arrested by the Gestapo in Lyon. Under terrible torture, he betrayed nobody; broken in body, he died eleven days later, while being taken eastward, already unconscious, to a concentration camp in Germany.

All over the world, total war had dragged hundreds of thousands of human beings into camps where the guards and administrators participated in the torture and death of the inmates. Notorious in this regard were the camps on the Thailand railway. Recording the first death in Hintok camp, that of a private soldier, E. L. Edwards, on June 2, Colonel Dunlop noted in his diary: ‘God knows the angel’s wings must have been over us in view of the terrible mortality in all other camps up and down this line which seemed to be being built in bones.’ As for Konyu camp, Dunlop noted, it was ‘a real camp of death these days—at least an average of one death a day, and five in one day recently’. The prisoners-of-war were being made to get up ‘in pitch dark and wet, leave with the first light after boiling their morning rice, and return again in darkness after a gruelling day in the rain and mud’.

***

On June 2 the German Air Force launched a series of attacks on Kursk; on the following day the Russian Air Force struck at German formations in Orel. In Algiers, June 3 saw the final day of the conference between Churchill and the Anglo-American service chiefs at which it was agreed to launch Operation Tidal Wave, the bombing of the Roumanian oilfields at Ploesti. Approval was also given for the bombing of the Italian railway marshalling yards in Rome. The bombing of these yards, advised General Marshall, ‘should be executed by a large force of aircraft’.

For the Germans, the problems behind the lines continued. On June 3 they launched Operation Cottbus against Soviet partisans in the Polotsk—Lepel—Borisov region. At Clermont-Ferrand, in France, a Resistance unit struck that day at the Michelin tyre factory, destroying more than three hundred tons of tyres.

The Germans fought against their enemy behind the lines with the same energy as at the front. During Operation Cottbus, five thousand Russian villagers, including many women and children, were killed because partisans had found shelter in or near their villages. Yet only 492 rifles had been captured, in an area in which several thousand partisans were operating; on June 5 a German report noted with alarm that in the largest partisan centres there were airstrips on which it was possible to land two-engined aircraft, to fly in men and arms, and to evacuate fifteen to twenty wounded men on each flight.

The Final Solution also continued to be put into effect day by day. In Warsaw, on June 3, German troops discovered 150 Jews hiding in a bunker under the ruins of the ghetto; the bunker was destroyed. In the town of Michalowice, two Polish farmers, Stefan Kaczmarski and Stanislaw Stojka, were shot on June 3 for hiding three Jews. Two day later, in a slave labour camp at Minsk Mazowiecki, near Warsaw, all 150 Jewish slave labourers were shot dead, and the camp closed.

In German-occupied Western Europe, the escape lines for Allied airmen shot down were ensuring that hundreds of air crew never fell into German hands, but returned to Britain, and flew again, some of them within a few weeks of being shot down or baling out. On June 7, however, final disaster struck one of the main escape routes, the ‘Comet’ line, as five English airmen and one American were being met in Paris by two members of the line, Frederic de Jongh and Robert Ayle. Betrayed by a young Frenchman, the twenty-two-year-old Jacques Desoubrie, the six airmen were taken to prisoner-of-war camps and the two couriers to a Gestapo prison, where they were shot.

In all, Jacques Desoubrie was to be responsible for the arrest of fifty French and Belgian members of the Resistance, almost all of whom were then executed. On June 7, the day of the betrayal of the airmen in Paris, Professor Clauberg informed Himmler that the method on which he had been experimenting in Auschwitz, for the large-scale sterilization of women by X-rays, was ‘as good as ready’. Clauberg added: ‘I can now see the answer to the question you put to me almost a year ago about how long it would take to sterilize a thousand women in this way. The time is not far distant when I shall be able to say that one doctor, with, perhaps, ten assistants, can probably effect several hundred, if not one thousand sterilizations on a single day’.

There was no shortage of victims for these experiments; on June 8, more than eight hundred Greek Jews were deported from Salonica to Auschwitz, to be followed before the end of the month by a thousand Jews from Paris, and two thousand from the Upper Silesian city of Dabrowa Gornicza. From Germany, too, the few surviving Jews were being rounded up; that June, seventy Jews from Nuremberg, fifty-seven from Würzburg and eighteen from Bamberg were sent to Auschwitz. Also deported to Auschwitz that month were all the residents of the Jewish Old People’s Home in the Czechoslovak city of Moravska Ostrava.

In Lyon, on June 6, the head of the Gestapo there, Klaus Barbie, began the five-day interrogation and torture of a thirteen-year-old girl, Simone Legrange, whose family had been denounced by a neighbour as Jews in hiding. The whole family were then sent to Auschwitz, where Simone Legrange’s father was shot in front of her, and her mother sent to the gas chamber after being caught stealing a few discarded cabbage leaves. ‘Shot or deported’, Barbie told a local Jewish leader about the Jews whom he had arrested, ‘there’s no difference.’ Nor was there any ‘difference’ as far as the fate of members of the French Resistance was concerned; on June 9, in Paris, the Gestapo arrested Alexander Rochais, the fifty-six-year-old head of the sixth section of the Paris Resistance. Deported to Buchenwald, he was killed there three months later. Today, in the Rue St André des Arts in Paris, a wall plaque marks the house in which Rochais was seized.

In German-occupied Yugoslavia, on June 9, one of the two British officers on the mission to the Yugoslav partisans, Captain Stuart, was killed during an air attack on Tito’s headquarters. On the following night, the forces of Operation Black encircled Tito, his staff, an escort battalion and the three surviving members of the British mission. In the breakout, both Tito and the other British officer, Bill Deakin, were wounded, and more than a hundred partisans killed.

But Operation Black had failed; Tito’s forces, mauled and scattered, regrouped and fought on.

***

On June 11, after ten days of air and sea bombardment, British troops based in Tunis launched Operation Corkscrew, landing on the small Italian island of Pantelleria. The Italian garrison at once surrendered. On the following afternoon, after an intense naval and air bombardment, the Italian garrison on the island of Lampedusa surrendered unconditionally. A third Italian island, Linosa, surrendered on June 13, while an uninhabited island, Lampione, was occupied by the Royal Navy that same day. No military obstacle now stood between the Allies in Tunisia and the invasion of Sicily, planned for the second week of July.

***

In the prisoner-of-war labour camps along the Burma-Thailand railway, the arrival of cholera added to the hardships and perils. ‘I have just received news’, noted Colonel Dunlop on June 13, ‘that 130 British soldiers in the camp across the road died yesterday’, and he commented: ‘The cholera only hastened the end for these deathmasked men. Dehydration, in a black coat, is taking the victims painfully away’.

***

Hitler’s confidence that he could retain the mastery of Europe was not entirely shared by his subordinates, even in the SS, whose leader, Himmler, decided, in the summer of 1943, to begin the total destruction of the evidence of the mass murder of Jews and Soviet prisoners-of-war. The method chosen was to send special squads to every mass murder site, to dig up the bodies and to burn them. In charge of this massive operation, which was to take more than a year of intense activity, was an SS colonel, Paul Blobel, who had earlier been in command of one of the SS killing squads in German-occupied Russia. Blobel’s Special Commando Group No. 1,005, also known as the ‘Blobel Commando’, began work at the death pits near Lvov on June 15, when several hundred Jewish slave labourers at the adjacent Janowska concentration camp were taken to the pits and forced to dig up the putrefying corpses. Before burning them, the Jews were ordered to extract gold teeth and pull gold rings from the corpses. ‘Every day,’ one of the few survivors of a Blobel Commando, Leon Weliczker, later recalled, ‘we collected about eight kilogrammes of gold.’

On the day on which the Blobel Commando began its gruesome work at Lvov, the head of the German Concentration Camp Inspectorate, SS Major-General Richard Glueks, visited Auschwitz. He was not entirely satisfied with what he saw, noting that the gas chambers, which he described in his report as the ‘special buildings’, were not well located, and ordered them to be relocated where it would not be possible for ‘all kinds of people’ to ‘gaze’ at them. One result of this complaint was the planting of a ‘green belt’ of fast-growing trees around the two crematoria nearest the camp entrance.

On the day of Glueks’s report, a new labour camp was opened in the Auschwitz region, at the coal mines of Jaworzno. On the following day, Himmler’s permission was given for eight Jews in Auschwitz to be sent to the concentration camp at Sachsenhausen, near Berlin, for experiments investigating jaundice. Five days later, in what Himmler called the interest of ‘medical science’, seventy-three Jews and thirty Jewesses were sent, alive, from Auschwitz to the concentration camp of Natzweiler, in Alsace. On reaching Natzweiler, their ‘vital statistics’ were taken. They were then killed, and their skeletons sent as ‘exhibits’ to the Anatomical Museum in Strasbourg.

Two hundred and fifty miles west of Natzweiler, in the triangle Orléans—Étampes—Chartres, just south of Paris, a member of the French Resistance was preparing to sabotage German railway and telephone targets. On June 16 a wireless operator was sent into France to join him. Her name was Noor Inayat Khan, an Indian princess, and a direct descendant of Tippoo Sultan. Bilingual in French and English, given the code name ‘Madeleine’, she did invaluable work until, arrested as a result of a betrayal, she was shot at Dachau in September 1944.

A sense of urgency now gripped the German racial plan. Even as the Blobel Commando began its task of destroying the physical evidence of mass murder, the process of murder was accelerated. ‘Responding to my briefing on the Jewish question,’ Himmler noted at Obersalzberg on June 19, ‘the Führer declared that the evacuation of the Jews, regardless of the disturbance it will provoke in the next three to four months, must be ruthlessly implemented and endured to the end.’

In Eastern Galicia, more than twenty thousand Jews were murdered in fields and ditches that June, the gas chambers at Belzec having stopped their work to enable a Blobel Commando to burn the bodies, crush their bones with a special machine and scatter the ashes. When this particular Commando, made up entirely of Jewish slave labourers, was sent on to Sobibor, its members, fearing that they were about to be gassed, tried to flee from the station; they were all shot down.

***

On June 20, British bombers launched Operation Bellicose, the first ‘shuttle bombing’ raid of the war. Leaving airbases in Britain, the bombers struck at the steel construction works at Friedrichshafen in southern Germany before flying on to airbases in Algeria; then, on their return flight to Britain, they bombed the Italian naval base at La Spezia. Unknown to the British, the Friedrichshafen works also contained the assembly factory for the V2 rockets, with an intended rate of assembly of three hundred rockets a month. So effective was the bombing, that the assembly line was abandoned.

Between the Friedrichshafen and La Spezia flights, a second air raid had been launched against the German industrial city of Wuppertal, in the Ruhr; not only was enormous damage done to factories in the city, holding up industrial production for nearly two months, but, in a second firestorm within two months, a further three thousand of its citizens were killed. Even British newspapers commented on the comparison with the German raid on Coventry, where 568 civilians had been killed and Coventry’s factory production halted for a month.

Each day saw a further Allied bombing attack on Germany; on June 22 the United States Eighth Air Force attacked a synthetic rubber factory at Hüls, in the Ruhr, putting it out of action for several months.

***

In the Pacific, American Marines were slowly extending the range of their operations, landing on June 22 on Woodlark Island in the Trobriand island group, and, also on June 22, reinforcing the existing units which had landed on New Georgia Island. Following up their success on Woodlark Island, American units landed on Kiriwina Island, the largest in the Trobriand group, on the night of June 23. A week later, General MacArthur launched Operation Cartwheel, a series of amphibious assaults with the object of regaining Rabaul. That day, American troops landed on Rendova Island. Beach by beach, island by island, the reconquest of the Pacific had begun. In almost every instance, the Japanese resisted as if they were on their own soil of Japan; but, by the end of June, the Allies had secured the domination of the Solomon Sea.

***

In the third week of June, Churchill gave orders for air supplies to Tito’s partisans to have priority ‘even over the bombing of Germany’. The air resources needed to send up to five hundred tons of arms and equipment a month to the Yugoslav partisans would, he told the British Chiefs of Staff on June 23, be a ‘small price to pay’ for the diversion of German and Italian forces caused by resistance in Yugoslavia. ‘It is essential to keep this movement going’, Churchill insisted.

***

On June 23, as Churchill put his authority behind increased help to Tito’s partisans in Yugoslavia, Hitler, at Obersalzberg, was justifying the deportation of Jews, following a protest by Henrietta von Schirach—daughter of his photographer Heinrich Hoffman and wife of the Governor of Vienna, Baldur von Schirach—who, on a recent visit to Amsterdam, had seen Jews being loaded into railway wagons. The sight, she told Hitler, was ‘horrifying’, and she went on to ask him: ‘Do you know about it? Do you permit it?’ In reply, Hitler told Schirach’s wife: ‘They are being driven off to work, so you needn’t pity them. Meantime our soldiers are fighting and dying on the battlefields!’ Hitler added: ‘Let me tell you something. This is a set of scales’—and he put up a hand on each side to signify the pans—‘Germany has lost half a million of her finest manhood on the battlefield. Am I to preserve and minister to these others? I want something of our race to survive a thousand years from now.’

Hitler’s final injunction was: ‘You must learn how to hate!’ Two days later, a thousand Jews were deported from Czestochowa to Auschwitz. As the deportation began, members of the Jewish Fighting Organization, led by Mordechai Zylberberg and Lutek Glickstein, distributed their few weapons, and sent their members to prearranged position in the cellars. But the Germans stormed the cellars, and most of the fighters were killed. The Jews had been poorly armed: the Germans captured thirty grenades, eighteen pistols and two rifles. Six fighters, commanded by Rivka Glanc, were cut off by the Germans. They had only two pistols and a single grenade. All six were killed.

Also on June 25, the Germans launched Operation Seydlitz, against Soviet partisans near Dorogobuzh, a vital communication centre for German reinforcements immediately behind the front line. That night, in German-occupied France, the British agent Michael Trotobas, known as Captain Michel, led a raid on the German locomotive works at Fives, on the outskirts of Lille. ‘This job will be done with finesse and not with force’, was Trotobas’s advice to the small Resistance group which he assembled, and which, after bluffing its way into the works, managed to plant and detonate twenty-four powerful explosive charges. In triumph, Trotobas signalled back to London: ‘Mission completed’.

***

That month, in what had become known as the Battle of the Ruhr, British bombers dropped fifteen thousand bombs in twenty nights. On June 27, Australia’s representative on the British War Cabinet, Richard Casey, one of Churchill’s weekend guests, noted in his diary how, ‘in the course of a film showing the bombing of German towns from the air (made up from films taken during actual bombing raids) very well and dramatically done’, Churchill suddenly ‘sat bolt upright and said to me “Are we beasts? Are we taking this too far?”’

Casey himself had no doubt as to the answer. ‘I said that we hadn’t started it’, he wrote, ‘and that it was them or us.’ On the following night, British bombers struck at Cologne, as well as at the Italian cities of Livorno and Messina. It was the raids in Italy and Sicily, not those on the Ruhr, which were to have an immediate impact on German strategy. Fearful of Italy’s defeat, or defection, the German Air Force moved two operational command stations from southern Russia to Italy. This fact was made known to the British by an Enigma message.

The Russians themselves were now making inroads into Germany’s Enigma system, having captured that June a code used by the German Air Force for air-to-ground signalling. In Murmansk, British and Soviet Naval Intelligence experts met to discuss how best to use the German air and naval messages thus procured. Shortly afterwards, the British presented the Russians with a captured Enigma machine, and a book of instructions for its use.

In a broadcast on June 30, Churchill spoke of the impending assault on Italy, and of Italian speculation as to where the assault would come. ‘It is no part of our business’, he said, ‘to relieve their anxieties or uncertainties.’ Churchill also spoke of the ‘frightful tyrannies and cruelties’ with which the German armies, ‘their Gauleiters and subordinate tormentors’ were now afflicting so much of Europe, and he declared: ‘When we read every week of the mass executions of Poles, Norwegians, Dutchmen, Czechoslovaks, Frenchmen, Yugoslavs, and Greeks; when we see these ancient and honoured countries of whose deeds and traditions Europe is the heir, writhing under this merciless alien yoke, and when we see their patriots striking back every week with a fiercer and more furious desperation, we may feel sure that we bear the sword of justice, and we resolve to use that sword with the utmost severity to the full and to the end’.

***

On July 1, Hitler returned to his ‘Wolf’s Lair’ headquarters at Rastenburg, where, in a briefing to the commanders of Operation Citadel, he set July 4 as the date for the start of the attack on the Kursk salient. Greater Germany, he explained, ‘must be defended far beyond our frontiers’. The principle on which this could be achieved was a simple one: ‘Where we are, we stay’—whether in Russia, Sicily, Greece or Crete.

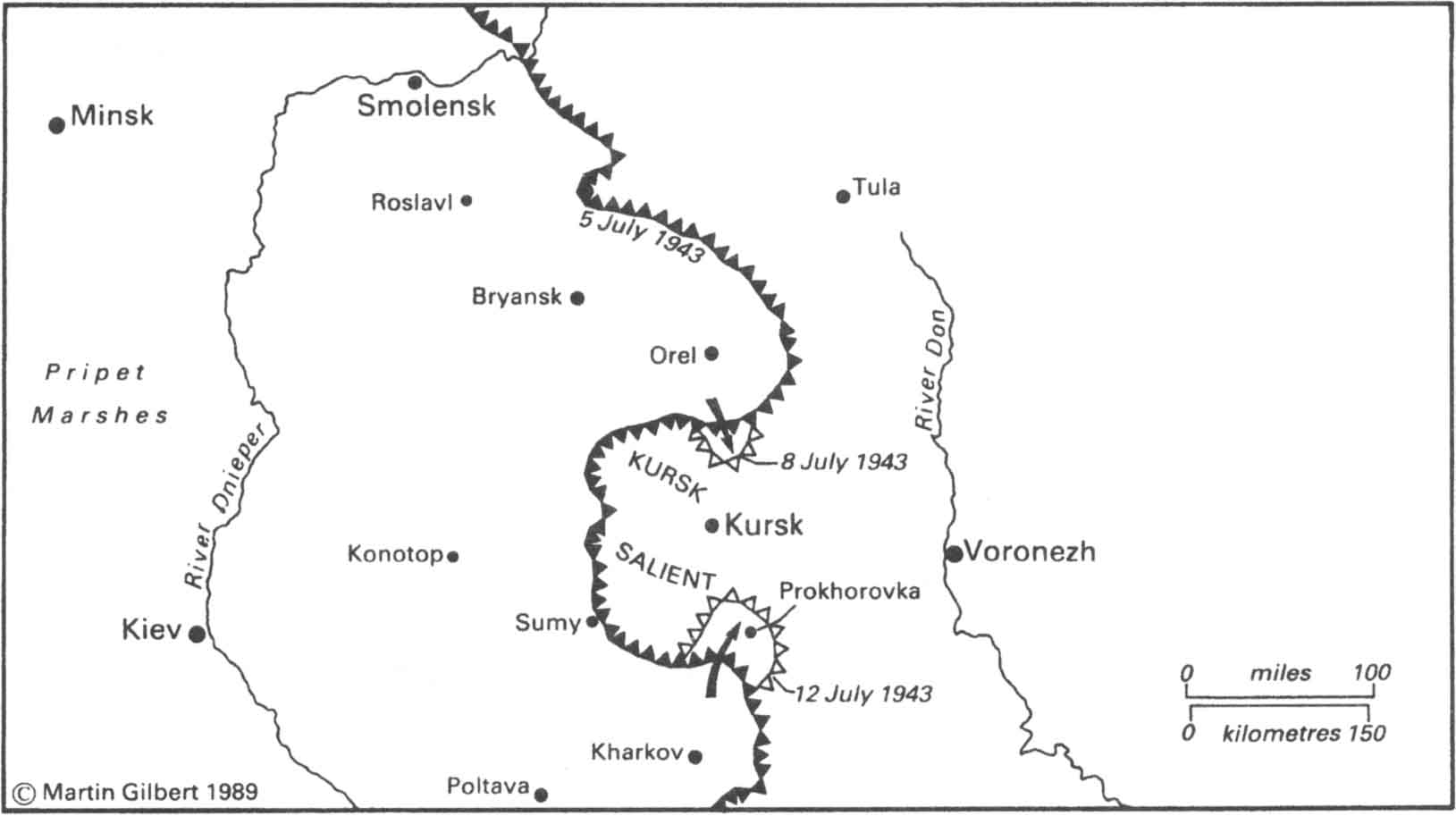

In one last attempt before the Kursk attack to cut down Soviet partisan activity behind the lines, on July 2 the Germans launched Operation Günther in the region of Smolensk. Two days later, Hitler sent a personal message to the soldiers around the Kursk salient. ‘This day’, it read, ‘you are to take part in an offensive of such importance that the whole future of the war may depend on its outcome. More than anything else, your victory will show the whole world that resistance to the power of the German Army is hopeless’. Then, in the very early hours of July 5, at 1.10 a.m., two hours and twenty minutes before the German offensive against Kursk was due to begin, the Russians opened an artillery bombardment on the German forming-up positions and artillery lines. Considerable damage was done, blunting the edge of the German attack and ending all the intended element of surprise. Then, at 3.30 a.m., exactly on schedule, the German offensive began.

The Battle for the Kursk Salient, July 1943

Along a two-hundred-mile front, the battle for the Kursk salient now absorbed the military energies, materials, willpower and hopes of each side; six thousand tanks—the biggest tank battle in history—and four thousand aircraft, were in combat. For Hitler, a relatively small bulge in the line had to be straightened. For Stalin, that same line had to be held, and Kursk retained.

The heroism of individuals was once more a feature of bloody, sordid war. On July 6, a Soviet pilot, Lieutenant Aleksei Gorovets, found himself alone in the sky above the salient facing twenty German aircraft. He decided to attack, and, having shot down the leader, shot down eight more. Then, unseen by Gorovets, four German fighters attacked him from above, and he himself was shot down. He was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

***

At dawn on July 10, five days after the start of the Battle of Kursk, and while its outcome was still undecided, Allied forces landed on the coast of Sicily, 160,000 men and 600 tanks putting ashore under the cover of an intense naval bombardment. Once again, the heroism of individuals was remarkable. One British officer, Major Richard Lonsdale, who was parachuted with his men too far inland because of high winds, nevertheless remained where he was and with his men fought off successive German attacks, until it was the Germans who withdrew. For his tenacity, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

That night, British units entered Syracuse, the first Italian city to be wrested from Italian rule. Inside German-occupied Europe, the news of this first Allied success in Europe was a cause for rejoicing, and for hope. On July 11, in the Kovno ghetto, Avraham Golub, who had been a lawyer in pre-war Lithuania, noted in his diary: ‘Yesterday afternoon the mood in the ghetto was excellent. The British radio had just broadcast the news about the invasion of Sicily by the Allied armies. This news had been brought by workers returning from the city; in no time it spread throughout the ghetto. Everyone was certain that the end is near; deep in our hearts we were very glad. Everyone regarded the invasion of Sicily as a most unusual event which might bring our own liberation closer. Optimists spoke about the surrender of Italy in the near future; about clashes between units of the Italian and German armies, and about the fiasco of the new German offensive in Russia’.

‘The Jews, of course,’ Golub added, ‘were busy drawing up plans for the Allied armies.’

On July 12, in the Kursk salient, the Russians faced their most serious test of the battle, when, at the village of Prokhorovka, they pitted nine hundred tanks against an attack by nine hundred on the German side; the German tanks included a hundred Tiger tanks, which were in many ways superior to the Russian T-34. The Russian officer responsible for holding the line, General P. A. Rotmistrov, later recalled: ‘The earth was black and scorched with tanks like burning torches.’ At one moment in the battle, Rotmistrov wrote, ‘the commander of a Soviet T-34 had been so badly injured by a shell that penetrated the tank and set it on fire that he had to be taken out and laid in the cover of a crater. At that moment, a German Tiger bore down on the already stricken T-34, whereupon Aleksandr Nikolaiev, the driver, clambered back into his damaged and smouldering tank, started up, and charged towards the German tank. The T-34 hurtled across the ground like a fireball; the Tiger halted, but it was too late. The blazing T-34 hit the German tank at full speed, and the explosion made the ground shake’.

At nightfall, the ‘slaughter of Prokhorovka’ ended. Three hundred German tanks, among them seventy Tigers, were strewn over the battlefield. Even more Russian tanks had been destroyed. But the German thrust had been halted. That same day, north of the salient battle, the Russians launched Operation Kutuzov against Orel, to force the Germans to dissipate their strength, and to deny them the chance of sending reinforcements from Orel to the Kursk salient. Although slow progress was made on the ground, this new Soviet attack showed the extent to which the ability to take strategic and tactical initiatives had now passed, after two years’ war in the East, from the attacker to the defender; henceforth, it was to be the defender, the Red Army, which would go over most frequently to the attack.

Far behind the lines, the German slaughters continued. On July 12, in the Polish village of Michniow, German police and Army units killed all two hundred villagers, including babies and expectant mothers, in yet another attempt to try to stamp out Polish patriotic feeling. On the following day, at the village of Sikory Tomkowieta, near Bialystok, a German military detachment executed forty-eight villagers, including fourteen children, for non-delivery of the agricultural produce which each village was obliged to hand over.

***

In the Pacific, 30,000 American troops were now ashore in the Solomon Islands battling against the fanaticism of the Japanese defenders. In Sicily, American, British and Canadian troops advanced northward across the island, against strong German and Italian opposition. In the Atlantic, British and American air and sea searches led to the sinking of seven German submarines in thirty-six hours, ‘the record killing of U-boats yet achieved in so short a time’, Churchill informed Roosevelt on July 14.

By July 14, it was clear that the Germans attacking towards Kursk were to be cheated of their prize. More than three thousand German soldiers had been killed and three thousand German tanks destroyed. The Russians had also captured an astonishing total of five thousand motor vehicles, 1,392 aircraft and 844 field guns. Several thousand Russian soldiers had also been killed, but, by holding Kursk, the Red Army had shown that even a relatively limited German aim could now be stopped. Summoning Field Marshals von Kluge and von Manstein to Rastenburg, Hitler told them that Operation Citadel was to be called off.

As Hitler decided, for the first time, to abandon a planned advance after only eight days, the Russians took yet another initiative, with a proclamation by the Soviet Supreme Command on July 14 that a ‘Rail War’ had been declared on the whole German rail system behind the lines. Six days later, on the Gomel—Bryansk—Orel railway, hundreds of miles of railway track were made impassable.

Not only resistance, but also retribution, now came into prominence, with the opening in Krasnodar on July 14 of the first Russian war crimes trial; eleven Germans were accused of the mass murder of Soviet civilians during the German occupation of the region. Eight Germans were sentenced to death and shot. Their trial, which was attended by several Allied journalists, did much to establish in Western minds the scale and nature of Nazi atrocities, and in particular the use of ‘murder vans’, inside which the victims were locked, and then gassed. Evidence was produced during the trial to show that some seven thousand civilians had been killed in this way in Krasnodar alone. ‘Men, women and children’, the court was told, ‘were bundled into the van without discrimination,’ including most of the patients in the Municipal Hospital. ‘The gravely sick patients’, one witness stated, ‘were brought out on stretchers and the Germans flung them in the van too.’ The van was then driven to a specially dug anti-tank ditch on the outskirts of the city. By the time it arrived, all those in it had been gassed. Their bodies had then been dumped into the ditch.

Even as the Krasnodar trial was in progress, killings such as it was revealing to the shocked Western observers continued to be carried out; on July 18, two hundred Jewish slave labourers were killed in the Polish town of Miedzyrzec Podlaski, followed two days later by a further five hundred in Czestochowa. That month, also, two hundred Jews were deported from Paris to Auschwitz, and a further 1,500 from the camp at Malines, in Belgium, where several thousand Belgian Jews were interned. In the German war against Soviet partisans, during which so many local villagers were also killed as a warning and a reprisal, July 15 saw the launching of Operation Hermann, a month-long sweep between Vilna and Polotsk.

***

In Sicily, German forces defending Biscari airfield had for three days inflicted heavy casualties on the attacking Americans, before being forced to withdraw. In a final skirmish on July 14, after twelve American infantrymen had been wounded by sniper fire, a group of thirty-six Italians, some of them in civilian clothes, surrendered. On the order of the American company commander they were lined up along the edge of a nearby ravine and shot. That same day, another American infantry company ordered forty-five Italian and three German prisoners-of-war to be sent back to the rear for interrogation. After they had gone about a mile, the sergeant of the escort ordered them to halt, declared that he was going to kill the ‘sons of bitches’, borrowed a sub-machine gun, and shot the prisoners down.

When General Bradley heard of this incident, and reported it to General Patton, it was Patton who instructed him ‘to tell the officer responsible for the shootings to certify that the dead men were snipers or had attempted to escape or something, as it would make a stink in the press and also would make the civilians mad. Anyhow, they are dead, so nothing can be done about it.’ Bradley refused, and the two men were court-martialled, the sergeant, Horace T. West, being found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment, the officer, Captain John T. Compton, being found not guilty. Because of a sustained outcry about unfair discrimination between officers and men, Sergeant West was released from confinement after a year, and returned to active service. Captain Compton had already been killed in action.

***

In the air above the Kursk salient, the bravery of the Soviet pilots included several whose exploits have entered into legend. One, Alexei Maresyev, had earlier had both his legs amputated, as a result of injuries incurred when he had been shot down over German-held territory. He had managed to crawl back, in eighteen days, to the Soviet lines. Also in action at Kursk were the French pilots of the Normandy Squadron, several of whom were killed in action, and whose commander, Major Jean-Louis Tulasne, shot down a total of thirty-three German planes.

On July 16, the Germans began their withdrawal in the Kursk salient. In Sicily, German forces began to fall back towards Catania. That day, Roosevelt and Churchill issued a joint appeal to the Italian people, urging them to decide ‘whether they want to die for Mussolini and Hitler or live for Italy and civilization’. Three days later, on July 19, as American bombers attacked the railway marshalling yards in Rome, Hitler travelled to Italy, to meet Mussolini at Treviso, and to lecture him for two hours on how to fight wars and battles. ‘Duce unable to act as he would wish,’ Rommel noted in his diary after a talk with Hitler on July 20, and he added: ‘I am to take command over Greece, including the islands, for the time being, so that I can pounce on Italy later.’ Rommel’s Greek assignment had an urgent purpose; German Army Counter-Intelligence still believed that Greece, not Sicily, was the principal and imminent target of the Allied strategists.

In Sicily, a major political objective was secured on July 22, when American troops entered Palermo, the principal town on the northern coast. Two days later, in Rome, the Fascist Grand Council, in a gesture of defiance against Mussolini, asked King Victor Emmanuel to assume ‘effective command’ of Italy’s armed forces, and called for the responsibilities of Crown and Parliament to be ‘immediately restored’.

The oldest of the Axis dictatorships was being undermined. Within twenty-four hours, Mussolini had been informed by the King that the Government of Italy had been placed in the hands of Marshal Badoglio.

Benito Mussolini, ruler of Italy since 1922, was suddenly, and with no apparent means of redress, shorn of his powers. Not only that; in an ignominious end to his authority, an ambulance hurried him from Rome to the island of Ponza, ‘to safeguard his person against public hostility’.

That July 24, as Italy was in the throes of a sudden, bloodless revolution, Leningrad received the heaviest German shelling of the war; 210 people were killed, including several dozen in a tram on the Liteiny Bridge. In Britain, the civilian death toll from German bombing that July was 167. But on the night of July 24, British bombers set out on the first raid of Operation Gomorrah, against Hamburg, dropping 2,300 tons of high explosive and incendiary bombs in a few hours, as much as the combined tonnage of the five heaviest German air raids on London. ‘All Hamburg seems to be in flames,’ Berlin radio announced on the following morning. More than 1,500 German civilians had been killed. Nor was that the end of Hamburg’s troubles that July; in conjunction with Operation Gomorrah, which continued to pound Hamburg night after night, the American Eighth Air Force launched ‘Blitz Week’, flying 1,672 sorties over northern Germany, including two raids against Hamburg, two against Kassel and two against Kiel.

In the first of the Gomorrah raids on Hamburg, the British had used a hitherto secret radar-jamming device, ‘Window’, bales of ten-and-a-half-inch strips of aluminium foil which were pushed out of the bombers as they flew to their target, and as they returned from it, to confuse the German radar watchers by a veritable snowstorm of ‘aircraft’ on their screens. As a result of the use of ‘Window’ on July 24, only twelve of the 791 bombers sent on the mission were shot down. On past averages, the new device had saved between seventy and eighty aircraft, and several hundred lives.

For Hitler, this Allied bombing success was part and parcel of a sudden worsening of the war. First, he had been cheated of victory at Kursk, then he had seen, in quick succession, the invasion of Sicily, the fall of his fellow dictator in Rome, and now the massive destruction of a German city. On July 26 he was forced, in order to prepare for the transfer of troops to Italy, to order Marshal von Kluge to begin the evacuation of his troops from the Orel salient. ‘The fact is’, General Jodl told Hitler that day, ‘the whole fascist movement went pop, like a soap bubble.’

Both the King of Italy and Marshal Badoglio, the successor to Mussolini, had declared that Italy would continue to fight the war at Germany’s side. But their promise gave no comfort to those at Rastenburg. ‘In spite of the King’s and Badoglio’s proclamation,’ Rommel wrote in his diary on July 26, ‘we can expect Italy to get out of the war, or at the very least, the British to undertake further major landings in northern Italy.’ As for the war itself, Rommel noted, ‘The Americans have meanwhile occupied the Western half of Sicily and have broken through’.

Hitler had now to plan for military operations in Italy, in the most unfavourable circumstances, effectively calling a halt to any further advances on the Eastern front, where he had so hoped to reverse the humiliation of Stalingrad. Suddenly, it was in Western Europe, at his own back door, that danger threatened. At Rastenburg, on July 27, he therefore approved Operation Oak Tree for the personal ‘liberation’ of Mussolini, and Operation Student for the German occupation of Rome and the restoration of a Mussolini government, hoping to forestall an Allied landing as far north, so Rommel feared, as Livorno or even Genoa.

For the Allies, the events of the last week of July were an auspicious omen. ‘The massed, angered forces of common humanity’, Roosevelt told the American people during his Fireside Chat broadcast on July 28, ‘are on the march. They are going forward—on the Russian front, in the vast Pacific area, and into Europe—converging upon their ultimate objectives, Berlin and Tokyo.’ As for the events in Italy, Roosevelt declared, ‘The first crack in the Axis has come. The criminal, corrupt fascist regime in Italy is going to pieces.’

On the night of July 27, the last Japanese forces on Kiska Island in the Aleutians had slipped away; they had decided not to do battle. On New Georgia Island in the Pacific, however, the Japanese, determined not to yield except at the highest possible cost, continued to fight for every position, forcing the Americans to call for reinforcements on July 28. Nevertheless, everywhere that they were in action, the Japanese were in retreat.

Over Germany, the early hours of July 28 saw the climax of Operation Gomorrah against Hamburg, which had already lost 1,500 of its citizens during the British air raid four days earlier. The raid of July 28, although it lasted only forty-three minutes, was different from any that had proceeded it in more than three years of aerial bombardment. ‘The burning of Hamburg that night’, one flight lieutenant later recalled, ‘was remarkable in that I saw not many fires but one. Set in the darkness was a turbulent dome of bright red fire lighted and ignited like the glowing heart of a vast brazier. I saw no flames, no outlines of buildings, only brighter fires which flared like yellow torches against a background of bright red ash. Above the city was a misty red haze. I looked down, fascinated but aghast, satisfied yet horrified. I had never seen a fire like that before and was never to see its like again’.

A lethal predominance of incendiary bombs in the 2,326 tons of bombs dropped, combined with a warm night with low humidity, and a fire fighting service which had not recovered from its efforts four days earlier, led to a new phenomenon in the history of aerial warfare, described by the Hamburg Fire Department that night in the single word: ‘firestorm’. One factory worker engaged in trying to save his factory from the flames later recalled: ‘Then a storm started, a shrill howling in the street. It grew into a hurricane so that we had to abandon all hope of fighting the fire. It was as though we were doing no more than throwing a drop of water on to a hot stone. The whole yard, the canal, in fact as far as we could see, was just a whole, great massive sea of fire’.

At the centre of the firestorm, a hurricane style wind was created which uprooted trees. Flames, driven by the wind, burned out eight square miles of the city during an eight hour inferno. By morning, more than forty-two thousand German civilians were dead. This was more than the total British civilian deaths for the whole of the Blitz.

More than thirty-five thousand residential buildings, a third of those in Hamburg, were totally destroyed. Remarkably, however, within a few weeks, Hamburg’s war production began to exceed that of the pre-firestorm levels.

***

In the early hours of July 29, Churchill and Roosevelt spoke on the telephone about their imminent armistice negotiations with Italy, secret contacts for which had already been made. ‘We do not wish’, Churchill told Roosevelt, ‘to come forward with any specific armistice terms before we are asked in so many words,’ to which Roosevelt replied: ‘That is right’. ‘We can wait one or two days’, Churchill said, to which Roosevelt answered: ‘Right.’ The two leaders then discussed the problem of British prisoners-of-war in Italy, in order to forestall their transfer to what Churchill described as ‘the land of the Hun’. He would communicate on this directly to the King of Italy, Churchill explained; Roosevelt agreed to do likewise.

This telephone conversation, revealing how close the Allies must be to taking Italy out of the war, was intercepted by German Intelligence, and shown to Hitler on the morning of July 29. Then, on the morning of July 30, he was shown a message from the German Security Police chief in Zagreb, Siegfried Rasche, reporting that the Chief of the Italian General Staff, General Roatta, had confided to a senior Croat general that ‘Badoglio’s assurances are designed merely to gain time for the conclusion of negotiations with the enemy’.

There was further distressing news for Hitler on the morning of July 30. In the third of the Gomorrah raids on Hamburg, mostly on suburban areas, a further eight hundred civilians had been killed, including 370 asphyxiated in a bomb shelter underneath a department store where the reserves of coke kept there caught fire. If three or four more cities were bombed as Hamburg had been, Albert Speer told Hitler, it could lead ‘to the end of the war’.

Blow after blow seemed now to fall on Germany’s war-making effort; on July 31, Churchill informed Roosevelt that eighty-five German submarines had been sunk in the previous ninety-one days of battle in the Atlantic. In Russia, behind German lines, the ‘War of the Rails’ intensified in the first days of August 1943, with Soviet partisans placing 8,600 explosive charges on the railway lines of Army Group Centre. On August 1, as part of Operation Tidal Wave, 177 American bombers flew from bases at Benghazi to the Roumanian city of Ploesti, putting forty per cent of the oil-refining plants out of action. For Hitler, the loss of this oil, not too serious in itself, as it took only a few days to restore production to the level needed by Germany, was nevertheless an ill omen of things to come. For the Americans, there was little comfort in a mission which resulted in the loss of fifty-four bombers and 532 aircrew. But a further twenty raids were to go ahead, until Tidal Wave brought production to a halt twelve months later.

***

In the Pacific, on August 1, Japanese aircraft bombed the American PT—fast patrol—boat base at Rendova Island, one of the Solomon Island chain, killing two men. The aim of the raid had been to deter PT activity against a force of four Japanese destroyers which were taking essential war supplies to the Japanese forces at Vila, on the southern tip of Kolombangara Island. Undeterred, fifteen PT boats set out from Rendova that evening, but failed to halt or harm the destroyers, despite a series of torpedo attacks upon them. During the engagement, one of the PT boats, PT-109, was rammed by the Japanese destroyer Amaqiri and cut into two pieces. So violent was the explosion at the moment of impact that the other PT boats assumed that PT-109 had been destroyed, and, returning to Rendova, prepared to hold a memorial service for the lost crew.

The crew had, however, survived, and, during a five-hour ordeal, clinging to some heavy timber from the boat, made for the shore of a small coral island. That evening, one of the eleven surviving crew members decided to swim out to sea, in the hope of being able to flag down any of the PT boats that might pass that way during the night. His name was John Fitzgerald Kennedy. When no PT boats came by, he began to swim back to the coral island, but was swept off course by the current. Returning with difficulty to the island, Kennedy was taken ill; two days later, he and his fellow crewmen decided to swim to a larger island, in fact Cross Island, which they believed to be Nauru Island. There, two native Solomon islanders agreed to take a message southward; Kennedy scratched it on a coconut shell. The message read: ‘Nauru Is. Native knows posit. He can pilot. 11 alive need small boat.’

Kennedy hoped that the coconut message would be taken to one of the Australian coast watchers who, working for Allied Intelligence, and amid daily risk and danger, kept a vigilant eye along the enormous and predominantly unguarded island coastlines in the Solomons and New Guinea island chains, and who were themselves largely dependent for their survival on the goodwill of the native islanders. His hope was fulfilled; the coconut was handed to Lieutenant Arthur Evans, a coast watcher on the unoccupied Gomu Island, next to the Japanese held island of Wana Wana. Evans at once replied: ‘Have just learned of your presence on Nauru Island and also that two natives have taken news to Rendova. I strongly advise you return immediately to here in this canoe and by the time you arrive here I will be in radio communication with authorities at Rendova, and we can finalize plans to collect balance of your party’.

This message reached Kennedy on August 7; that afternoon, a Solomon islander, Benjamin Kevu, paddled him and his crewmen to Gomu Island. From there, a PT boat took them back to Rendova. Later, Lieutenant Kennedy was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal, for gallantry in action. Later still, when President of the United States, he welcomed both Arthur Evans and Benjamin Kevu to the White House, where the coconut with its scratched message, and Evans’s reply, had pride of place among his trophies and souvenirs.

***

In German-occupied Europe, the destruction of the evidence of mass murder had become a priority. But its gruesome course was not always easy. At the death camp of Treblinka, August 2 saw a revolt by those Jews who were being forced to dig up the corpses and to burn them; men who knew that once their task was done, they too would be killed. Of the seven hundred Jewish slave labourers in the camp, more than five hundred were shot down during the revolt by the SS and Ukrainian guards, but more than 150 managed to escape. Some were subsequently hunted down by German and Ukrainian units and shot; others found safety in Polish homes, or went into hiding. As they did so, the Red Army launched an offensive against the German forces withdrawing from Orel, breaking into the city on August 4. Then, to the south, Soviet forces drove towards Kharkov, retaking Belgorod on August 5.

***

In Sicily, British troops entered Catania on August 5. On the following day, off Kolombangara Island, the Americans sank three Japanese destroyers bringing reinforcements to the island, drowning 1,500 soldiers and seamen. There were no American losses. Over Italy, throughout the second week of August, British bombers dropped more than six thousand tons of bombs on Milan, Turin and Genoa, killing several hundred Italian civilians. In Germany, a small group of officers, academicians, churchmen and professional men, about twenty in all, shocked by both the military setbacks and the moral turpitude of Hitler’s regime, drafted a document on August 9 in which they dedicated themselves to the overthrow of Nazism, and to its replacement by a new political and social ethic. Led by two members of the old German military aristocracy, Count Helmut von Moltke and Count Peter Yorck von Wartenburg, the group met at Moltke’s family estate in Kreisau, Silesia; hence its name, the Kreisau Circle.

‘German hopes of victory are completely dwindling,’ the Swiss newspaper Neue Züricher Zeitung commented on August 10. ‘They have been replaced by a deep anxiety, as the people are convinced that the Party will not give in, even if more towns like Hamburg are erased.’ It was not only the Nazi Party that had set its heart against surrender. On August 9, Rommel had written to his wife: ‘The casualties in Hamburg must have been very high. This must simply make us harder.’

Such hardness was seen, not only in internal reaction to Allied bombing, but in external action against the continuing efforts of partisans and resistance fighters. On August 10, in Yugoslavia, General Löhr ordered retaliation ‘with shooting or hanging of hostages’ to each partisan attack, as well as the ‘destruction of the surrounding localities’. Against Greek partisans a similar severity was to be shown. When, on August 12, German troops found an arms cache in the village of Kuklesi, ten civilians were shot in reprisal, and the village burned down. Two days later, in a so-called ‘cleansing’ operation in the Paramythia—Parga region, eighty partisans were caught and killed, in reprisal for the death of a single German soldier.

***

In the Pacific, Japanese propaganda had begun to undermine the faith of the Filipinos that the Americans would ever be able to liberate them. On August 10, General MacArthur was asked to agree to a proposal to send in to the Philippines packets of cigarettes, matches, chewing gum, sewing kits and pencils, individually wrapped with the American and Philippine flags, and with MacArthur’s facsimile signature below the words, ‘I shall return’.

MacArthur noted on this suggestion, ‘No objections. I shall return!’ Several million Victory Packages were made up, and sent in by submarine.

***

On August 11, the German Army began the evacuation of its forces in Sicily. For six days, a total of seventy naval vessels, and a further fifty rubber boats, took 60,000 German troops across the Straits of Messina, together with a high proportion of their vehicles and weapons. The Allies, although warned by Ultra of the German withdrawal, no longer had the necessary reserve strength to stop this movement. As a result, the Allied armies’ task was to be the more difficult when, less than a month later, they invaded the Italian mainland.

On the Eastern Front, Hitler gave permission for the start of work on the construction of the ‘Panther Line’, a defence line to run from Narva on the Gulf of Finland to the Sea of Azov near Melitopol. Not only German Army engineers and rear-echelon troops, but slave labourers drawn from all over Europe, were to be used for the task: a massive bulwark of earthworks, concrete, barbed wire and mines.

For the Germans, the sense of ever-impinging Allied activity was heightened on August 13, when American bombers struck at the industrial city of Wiener Neustadt, twenty-seven miles from Vienna. This was the first Allied air raid over Austria. That same day, under conditions of strictest secrecy, a United States physicist, Norman F. Ramsey, organized the dropping of a scale model of the atomic bomb at the Dahlgren Naval Proving Ground in Virginia. Known as the ‘Sewer Pipe Bomb’, its test was a failure; but it was not long before the problem, stability in descent, was mastered.

In the Pacific, six thousand Americans landed on August 15 on Vella Lavella Island; there were not enough Japanese troops to impede their landing or seriously to hold up their advance. That same day, landing on the Aleutian island of Kiska, 29,000 Americans and 5,300 Canadians, supported by a hundred ships specially designed for the transport of tanks and armoured vehicles, landed at dawn, only to discover that the Japanese had gone.

***

That week, Churchill was Roosevelt’s guest for two nights at the President’s Hyde Park home. On August 13, using the code name ‘Boniface’ to disguise Enigma, he gave Roosevelt a document about the daily German killings of Yugoslav civilians: ‘I am not sure that your people have quite realised all that is going on in the Balkans and the hopes and horrors centred there. You might find it convenient to keep it by you. Much of it is taken from the Boniface sources, and it certainly makes one’s blood boil.’ ‘I must add,’ Churchill continued, ‘that I am not in any way making a case for the employment of an Allied Army in the Balkans but only for aiding them with supplies, agents and Commandos. Once the Adriatic is open we should be able to get into close contact with these people and give them aid sufficient to make it worth their while to follow our guidance.’

It was while Churchill was at Hyde Park that he and Roosevelt reached agreement on the full sharing of all work being done by British and American scientists on the atomic bomb. This agreement, signed by both men and shown to no one outside their most secret circle, placed the research and manufacture of the bomb in the United States, but as a joint project with no secrets withheld from either side. The first of the four Articles of Agreement laid down that Britain and the United States ‘will never use this agency against each other’. The second article stated: ‘We will not use it against third parties without each other’s consent’; the third, ‘that we will not either of us communicate any information about Tube Alloys to third parties except by mutual consent’. In the fourth article of agreement, covering the post-war industrial and commercial advantages of atomic research and development, Churchill, as the article noted, ‘expressly disclaims any interest in these industrial and commercial aspects beyond what may be considered by the President of the United States to be fair and just in harmony with the economic welfare of the world’.

From Hyde Park, Roosevelt and Churchill travelled to Quebec, where they and their most senior advisers, including the Combined Chiefs of Staff, agreed to allow General Eisenhower to negotiate with the Italian Government for the unconditional surrender of Italy. Then, on August 19, the combined Chiefs of Staff presented Roosevelt and Churchill with their conclusions, which the two leaders accepted. Germany was to be defeated before Japan. The cross-Channel landing, Operation Overlord, was to constitute the ‘primary United States-British ground and air effort against the Axis in Europe’, with its D-Day set for 1 May 1944. Its aim was not only to be a landing in northern France, but the undertaking of further operations from northern France ‘designed to strike at the heart of Germany and to destroy her military forces’.

One condition was set in the planning of Operation Overlord. If there were more than twelve German mobile divisions in France at the intended moment of the Allied landing, it would not take place. Nor would there be a landing if the Germans were thought to be capable of a build-up of more than fifteen extra divisions in the two months following the landing.

It was also decided at Quebec that the invasion of Italy would take place before the end of the month, with Naples as its objective. In the Balkans, Allied activity would be limited to sending supplies by air and sea to the partisans, to minor Commando raids, and to the bombing of strategic objectives.

***

On the morning of August 17, American forces entered Messina. After only thirty-nine days of fighting, the whole island of Sicily was under Allied control, and mainland Europe was within sight of the soldiers who crowded on the cliffs overlooking the Straits of Messina. That same day, American bombers based in Britain carried out heavy raids on the German ball-bearing factory at Schweinfurt and the Messerschmitt works at Regensburg. In the two raids, sixty of the five hundred attacking aircraft were shot down and more than a hundred aircrew killed, but both factories were badly damaged. During the bombing raid on Schweinfurt, 565 Germans, and 86 forced labourers of six different nationalities were killed. In Regensburg, there were 402 civilian dead, of whom 78 were foreign workers, most of them from Belgium, others from France, Russia, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary. The total Allied air crew deaths in the two air raids were 112 Americans, one Englishman and one Canadian.

That night, nearly six hundred British bombers carried out Operation Hydra, a long-planned raid on the German rocket and flying bomb construction centre at Peenemünde. During the raid, as a result of a deliberate decision by its planners, 130 German scientists, engineers and technical staff were killed in the housing estate on which they lived, among them Dr Thiel, who was responsible for the design of the rocket’s propulsion unit. Owing, however, to a mistake in the dropping of two of the marker bombs, a substantial proportion of the actual bombs fell on a nearby camp housing the foreign labourers; six hundred of them were also killed. Technically, the raid was a success, setting back production of the rocket by at least two months, forcing its production to be transferred to an underground factory being constructed by foreign labourers at Nordhausen, south-west of Berlin, and leading to the majority of the launching trials being moved to Blizna in Poland.

Goebbels was particularly angered by the Peenemünde raid, as a result of which, he wrote, ‘we can’t possibly count on reprisals before the end of January’. That night, the Chief of the German Air Staff, General Hans Jeschonnek, already under fire from Hitler for the Schweinfurt and Regensburg raids, committed suicide.

Despite the destruction at Peenemünde, one more rocket test was made from the Baltic coast. It took place on August 22, with a rocket which had been fitted with a dummy concrete warhead. The rocket came down, not in the sea, where it would have sunk without trace, but on the Danish island of Bornholm. There, the Danish naval officer in charge on the island, Lieutenant-Commander Hasager Christiansen, immediately photographed the rocket and managed to smuggle the photograph to Britain, together with some sketches which he had made. Two weeks later, Christiansen was arrested by the German occupation forces on Bornholm, and so severely tortured that he had to be transferred to hospital. After two weeks in hospital, a Danish resistance group smuggled him to Sweden. He was subsequently awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

***

On August 18 one of the more bizarre operations of the war took place. This was Plan Bunbury, the destruction of an electricity generating station at Bury St Edmunds, in East Anglia. A news item in The Times gave a brief description of this act of sabotage, which a German radio broadcast claimed to have resulted in the deaths of more than a hundred and fifty workmen. In fact, there had been no sabotage and no deaths; the news item had been a plant by British Military Intelligence, to give credence for their German ‘masters’ to two German agents, ‘Jack’ and ‘OK’, who had long before agreed to work for Britain, and whom their British masters knew as ‘Mutt’ and ‘Jeff’—after the popular cartoon characters.

The Eastern Front and the Red Army advance, July–August 1943

***

On August 22, after several days of stubborn fighting, German forces withdrew from Kharkov, and, for the fourth time in two years, the Ukrainian city changed hands. On the following evening, in Moscow, 224 guns each fired twenty salvoes to salute the troops who had liberated the city.

In a further discussion with Churchill at Quebec on August 23 Roosevelt seemed to take alarm at the turn of the tide in eastern Europe, telling Churchill that he ‘desired’ the troops of the Western Allies ‘to be ready to get to Berlin as soon as did the Russians’. On that day, the American and Russian troops were almost identical distances from Berlin, the Americans at Messina were 1,000 miles from Berlin, the Russians at Orel 950 miles away; yet, despite these great distances, which could surely not be covered for more than a year, Roosevelt showed concern about an eventual conflict of goals between the Soviet Union and the West. Churchill did not disagree.

Berlin was not merely a talking point that August 23; following the destruction of Hamburg, and the death of forty-four thousand of its citizens, at the end of July, British bombers had planned a new series of attacks, this time on Berlin, which were intended to wreak similar havoc. The first of these raids, in what the British were to call the Battle of Berlin, took place on the night of August 23, carried out by more than seven hundred bombers. When the raid was over, 854 people were dead, 102 of whom were foreign workers, and two of whom were Allied prisoners-of-war. British losses among the bomber crews were also high, with 298 airmen killed, and a further 117 taken prisoner and sent to prisoner-of-war camps.

More fortunate than those shot down over Berlin was Staff Sergeant Claude Sharpless, shot down near Toulouse on August 24. As he landed, thirty or more Frenchmen surrounded him, spirited away his tell-tale flying suit, and produced a suit of civilian clothes for him to change into, so that he could go into hiding and be guided southward to the Pyrenees, Spain, and safety.

***

On the Eastern Front, the Red Army followed up the recapture of Kharkov by continuing its advance, capturing Kotelva, sixty miles west of Kharkov, on August 27, and, west of Kursk, entering Sevsk that same day. Also on August 27, a total of 185 American bombers made a massive raid on the German rocket launching site at Éperclecques, on the Channel coast. The moment chosen for the raid was after the concrete had been poured, but before it had time to set; as a result, it was a mass of twisted steel reinforcing girders which hardened within a few days into a useless, distorted mass. The Germans had therefore to begin the construction all over again, and to do so at a new site. Following a meeting between Hitler and Albert Speer a month after the raid, the Chief Engineer of the Todt Organization, Xavier Dorsch, was authorized to build a million-ton concrete dome at nearby Wizernes. This project, embarked on when the strain of German resources was mounting to a climax, epitomized the hopes which Hitler placed in his novel weapons.

***

In Yugoslavia, Tito’s partisans, driven from Durmitor, had set up their headquarters at Jajce, two hundred miles to the north. There, on the night of August 27, they held their first national assembly, in the presence of Soviet, American and British officers. The session was held at night because of the danger of German air attack.

On the morning of August 28, a Yugoslav partisan leader, Ivo-Lola Ribar, and two British officers, Major Robin Weatherley and Captain Donald Knight, were about to fly from partisan headquarters to Cairo when a single German reconnaisance plane flew over the airstrip and dropped two bombs. The three men were killed. A month earlier, Ribar’s younger brother Jurica, an artist, had been killed fighting the Četniks in Montenegro; their mother was later murdered by the Germans for refusing to betray the men who had earlier helped her to flee from Belgrade. Ivo-Lola Ribar’s fiancée, Sloboda Trajkovic, who had refused to betray his whereabouts, had already been murdered by the Germans, together with her mother, her sister and her brother, at Banjica concentration camp, just outside Belgrade.

***

Since the fall of Mussolini in the last week of July 1943, the people of Denmark had felt a sense of excitement at the prospect of an eventual end to the tyranny of occupation. Resistance, especially strikes and sabotage, had increased since the defeat of von Paulus at Stalingrad; now it accelerated. On August 28, Hitler’s representative in Denmark, Dr Karl Rudolf Werner Best, presented an ultimatum to the Danish Government, demanding an end to strikes and meetings, as well as the introduction of a curfew, Press censorship and the death penalty for harbouring arms, and for sabotage. The Danish Government, supported by the King, refused the German demands. On August 29, without further negotiation, the German Army reoccupied Copenhagen, disarmed the Danish Army, and confined the King to his palace. For those Danes who had been active in the resistance, the German move provided a welcome end to Denmark’s existence as what they called ‘Hitler’s little canary’. But there were hardships too which would now have to be borne, and evils to be combated.

***

On August 30, the Red Army, advancing towards Smolensk, reoccupied Yelnya; in the south, on the Sea of Azov, the city of Taganrog was recaptured. On the following day south of Bryansk, after four days of fighting, two hundred villages and hamlets were liberated. That night, above the German capital, 613 British aircraft carried out the second raid of the Battle of Berlin. A total of 225 aircrew were shot down and killed, and a further 108 taken prisoner-of-war. The German deaths were only eighty-seven, a tenth the number of those killed in the city a week earlier, and a third of the British deaths. This reversal of the order of casualties was not, however, to impede or to delay the bombing of Berlin.

***

Four years had passed since the German invasion of Poland, the first military step of the Second World War. On that day, the war had been a conflict limited to two States. Within three days, Britain and France had joined as Poland’s allies. Now Poland was approaching a fifth terrible year of German occupation; and France had known more than three years of occupation. Yet Italy, which had joined in the war against France only when it was clear that France would fall, was now herself on the verge of defeat, and disaster. On September 1, the Italian Government replied to an Allied demand that its armistice terms should be accepted: ‘The answer is affirmative, repeat affirmative. Known person will arrive Thursday morning, 2 September, time and place arranged.’

In the Pacific, after a year and nine months of war, the United States was steadily regaining the ground which had been so swiftly and decisively lost. On September 1, American units landed on Baker Island, intent on transforming it into a base for air operations against the Japanese in the central Pacific. That same day, in an air attack launched from the decks of an aircraft carrier, American aircraft bombed Marcus Island, severely damaging Japanese military installations. All this was accomplished despite the priority given by the Americans to the war in Europe. On the following day, on the Eastern Front, the Red Army occupied the important railway junction of Sumy which, although recaptured from the Germans earlier, had then been lost.

Hitler did not intend to give up the struggle against any of his enemies. He was hoping to retrieve German fortunes through the tenacity of his soldiers, the disunity of the Allies, and the impact of various untried but novel weapons which included not only the V1 flying bomb and the V2 rocket, but also jet aircraft, and two revolutionary types of ocean-going submarines, one designed for high underwater speeds using conventional battery—diesel propulsion, the other powered by hydrogen peroxide, and both designed for operations against Atlantic convoys. Smaller versions of these submarines were also designed for operating nearer home against potential invasion forces.

On September 2, in an attempt to recover from the effect of the Anglo-American bombing raids on German industrial targets, Hitler appointed Albert Speer to be the head of a single controlling authority for industrial production, with authority even over the Minister of Economics, Walther Funk, who had hitherto controlled Germany’s raw material supply.

***

On September 3, the fourth anniversary of Britain’s declaration of war on Germany, the Western Allies launched Operation Baytown, the invasion of mainland Italy. At half past four that morning, formations of the British Eighth Army, commanded by General Montgomery, crossed the Straits of Messina to land at Reggio di Calabria. As British and Canadian troops came ashore, the Italian Government adhered to the terms of the armistice conditions, that no Italian troops would go into action against the invading forces. The armistice itself was signed in Sicily that afternoon, to come into public and formal effect in five days’ time. The German Army was now committed to defending a second front on the continent of Europe.