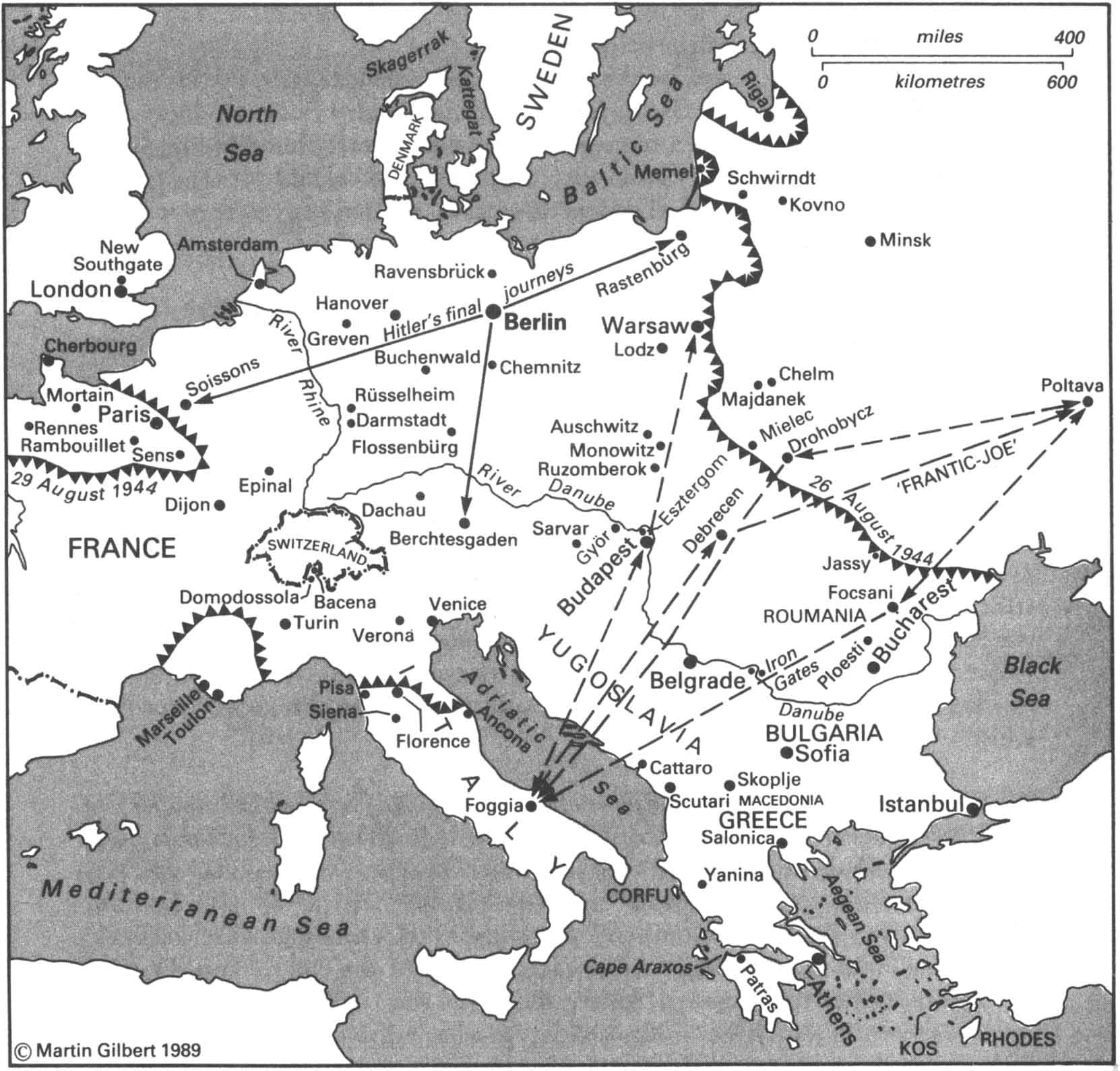

Europe at war, September 1944

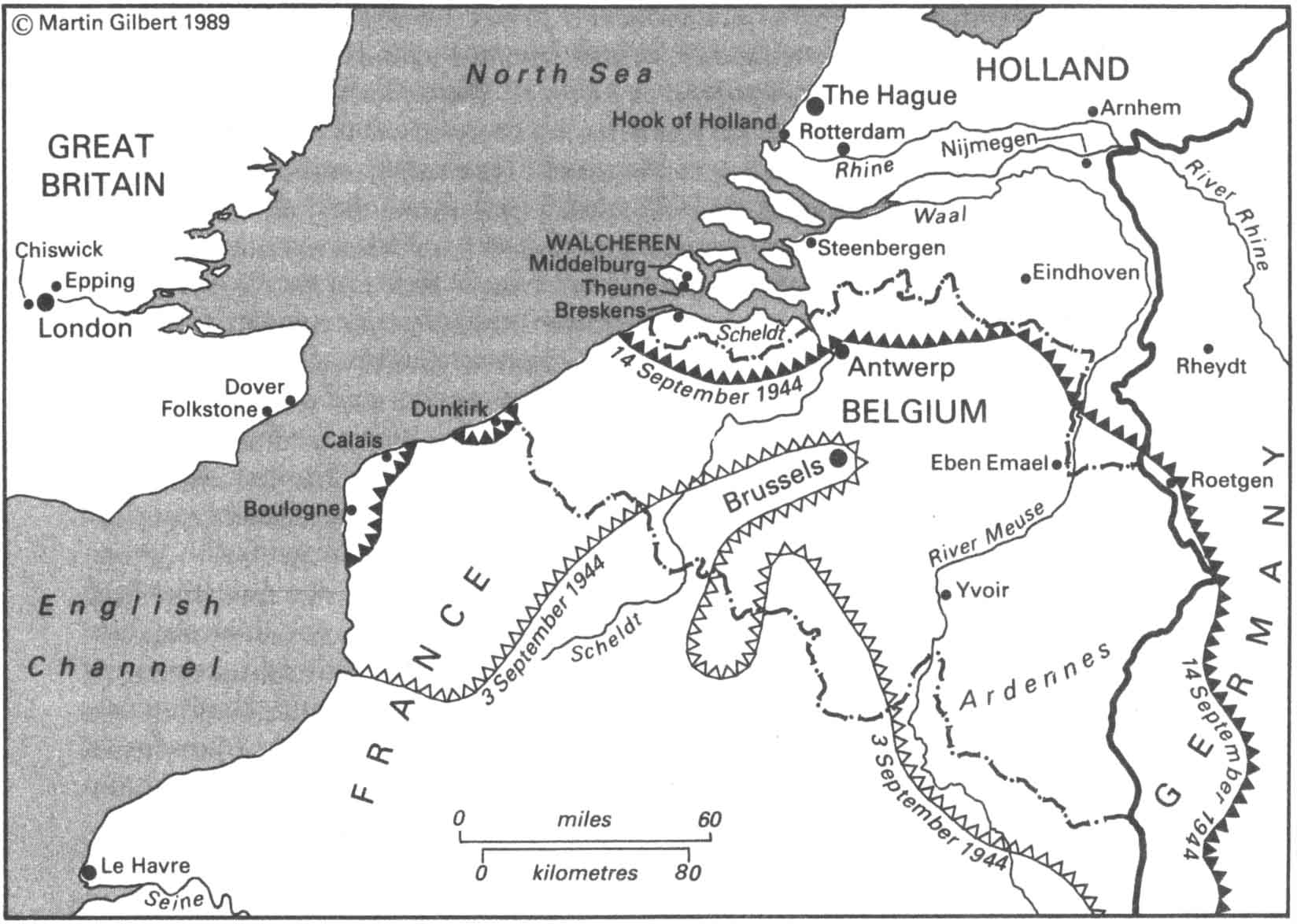

On 18 August 1944, the Communist-controlled National Council in Poland declared Lublin to be the temporary capital of Poland. In Warsaw, the insurgents fought on with growing desperation, against considerable German reinforcements, and without Soviet aid. That same day Churchill telegraphed to Roosevelt: ‘The refusal of the Soviets to allow US aircraft to bring succour to the heroic insurgents in Warsaw, added to their own complete neglect to fly in supplies when only a few score of miles away, constitutes an episode of profound and far reaching gravity. If as is almost certain the German triumph in Warsaw is followed by a wholesale massacre no measure can be put upon the full consequences that will arise’.

Anglo-American aid continued to be flown to Warsaw from southern Italy, but, of a total of 182 aircraft sent, 35 of them failed to return. Stalin, asked repeatedly to allow these aircraft to land at Soviet controlled airstrips to the east of Warsaw, refused. Angrily, Churchill wrote to his wife on August 18 of ‘the various telegrams now passing about the Russian refusal either to help or allow the Americans to help the struggling people of Warsaw, who will be massacred and liquidated very quickly if nothing can be done’.

There was no hesitation on the German side as to how to combat their enemies. On August 18 a train pulled out of Nancy railway station with 2,453 French political prisoners, locked into its wagons. They had come from the Gestapo prisons in Paris, and were on their way to Ravensbrück and Buchenwald. Less than three hundred of them were to survive their imprisonment there.

Thirty miles north of Nancy, a train reached Metz from Paris on August 19. In it was the body of Field Marshal von Kluge. He had committed suicide by taking a cyanide pill. In a final letter to Hitler, von Kluge wrote: ‘If your new weapons, in which such burning faith is placed, do not bring success, then, my Führer, take the decision to end the war,’ and he added: ‘The German people have suffered such unspeakable ills, that the time has come to put an end to these horrors.’

On the day of von Kluge’s suicide, Canadian, Polish and American troops launched their final attack to close the Falaise pocket.

On August 19, in Paris, the French police force, now loyal to the Resistance, seized the Préfecture de Police. A tricolour flag was raised, and the Marseillaise sung. When a single German armoured vehicle appeared, and opened fire with an automatic weapon, the police returned the fire. The battle for Paris had begun. A remnant of the German occupation forces was trapped by an increasingly active Resistance force, prepared to drive off any attempt by German soldiers to dislodge them. By nightfall, more than six hundred Germans had been taken prisoner. On the following morning, August 20, sixty members of the Resistance entered the Hôtel de Ville. Once inside it, they fired with rifles and pistols at any German vehicle which tried to approach. When two German trucks accidentally collided at Clichy, on the northern outskirts of the capital, the Resistance were able to get away with nine machine guns and twenty sub-machine guns; within forty-eight hours, there were more than seven thousand armed members of the Resistance, awaiting only the arrival of the Allies.

That same day, August 20, a British Special Air Service force, of sixty men and twenty jeeps, set off eastward from Rennes, working its way through the German lines to carry out a series of attacks on German units in a wide swathe behind the lines. Codenamed Operation Wallace, and commanded by Major Roy Farran, a veteran of similar exploits in Italy, it fought its way eastward through the forests of German-occupied France from just north of Orléans to Belfort. ‘I was most impressed’, Farran later recalled, ‘by the bellicose air of the French partisan’—and also by the sense of imminent liberation. During one skirmish, just east of Orléans, Farran noted, ‘a pretty girl with long black hair and wearing a bright red frock put her head out of a top window to give me the “V” sign. Her smile ridiculed the bullets.’

On several occasions, the men of Operation Wallace joined forces with the local French Resistance, to do battle with the retreating Germans. At Châtillon-sur-Seine one of Farran’s men, Parachutist Holland, was killed during a joint attack on the Germans in the town; today, a monument there recalls his sacrifice. Two more of Farran’s men were killed at nearby Villaines.

On August 20, in Lyon, 100 French men and women being held by the Gestapo were taken from prison to a disused fort of St Genis Laval, and shot. The bodies were then doused in petrol and set on fire. ‘While the fire was raging’, a French member of the Milice, Max Payot, later recalled, ‘we saw a victim who had somehow survived. She came to a window on the south side and begged her executioners for pity. They answered her prayers by a rapid burst of gunfire. Riddled with bullets and affected by the intense heat, her face contorted into a fixed mask, like a vision of horror. The temperature was increasing and her face melted like wax until one could see her bones. At that moment she gave a nervous shudder and began to turn her decomposing head—what was left of it—from left to right, as if to condemn her executioners. In a final shudder, she pulled herself completely straight, and fell backwards’.

***

In Paris, on August 20, the citizens awaited the arrival of the Western Allies. In the Falaise pocket, individual German units still fought on, in a series of suicidal attacks against units of the Polish forces. Inside Warsaw, the citizens fought on with increasing helplessness against overwhelming German force and brutality. On the Eastern Front, Soviet forces launched their offensive against Roumania along a three-hundred-mile front. At the end of its first day, five German divisions had been shattered, and three thousand German soldiers taken prisoner. The Roumanian forces in the line, commanded by General Abramescu, sought permission to withdraw to a more defensible line, but the Roumanian dictator, Marshal Antonescu, insisted that they remain in action. As a result, the Roumanian forces were crushed. After six days of continual advancing, the Red Army was poised to enter Focsani.

***

In what was left of the Falaise pocket, August 21 saw the last German effort to break out of the trap. In a final attack, on the Polish forces holding the trap closed, more than three hundred Poles were killed, but the position held, and a thousand Germans were taken prisoner. In all, during the Falaise battles, more than fifty thousand German soldiers had been taken prisoner, and ten thousand killed. Visiting the battleground two days after the last engagements had been fought, General Eisenhower later recalled: ‘Roads, highways and fields were so chocked up with destroyed equipment and with dead men and animals, that passage through the area was extremely difficult.’ It was, he added, ‘literally possible to walk for hundreds of yards at a time, stepping on nothing but dead and decaying flesh’.

***

On August 21, the Foreign Ministers of the Allied powers met at Dumbarton Oaks, a suburb of Washington, to establish a post-war system of collective security, designed to prevent future wars. Known as the United Nations Organization, its inner body was to be a Security Council, whose five member states—Britain, the Soviet Union, the United States, France and China—would each have the right of veto on any proposed measure to which they were opposed.

At that moment, however, it was not the possibility of future dissension among the Allies, but their impending victories, which were influencing the daily course of events. On August 22, as Soviet forces burst across the Roumanian frontier, capturing Jassy, King Michael of Roumania summoned Marshal Antonescu to the royal palace in Bucharest and ordered him to come to an immediate armistice with the Allies.

Antonescu refused, and was arrested. Also arrested was the German Ambassador, and the chief German military liaison officer in Bucharest. The King then ordered his troops to cease firing on the Russians. Hitler, caught by surprise, and unable to put into effect a recently prepared plan to occupy Roumania in the event of its defection, ordered his air units at Ploesti to bomb Bucharest. But the onward march of the Soviet forces could not be halted, and within a week more than 105,000 German soldiers had been killed, and an equal number taken prisoner.

As Roumania signed its armistice with Russia, the Finnish Government, which in the autumn of 1941 had helped the Germans to draw the ring of siege around Leningrad, announced that it too was ready to make peace with the Allies. Germany had lost its Axis partners at both the southern and northern extremities of the Eastern Front. In the Balkans, Greek and Yugoslav partisans intensified their attacks on German lines of communication, as the German forces in Greece and southern Yugoslavia, vulnerable to a Soviet thrust through Roumania, struggled to pull back from Athens, Salonica and Skoplje, to a defensive line between Scutari on the Adriatic coast and the Iron Gates on the Danube.

Europe at war, September 1944

In Italy, too, the partisan movement now felt strong enough to wrest whole valleys from German and Italian Fascist control; after a three day struggle, the Fascist stronghold in the mountain village of Bacena fell to the partisans on August 23. Within a week, all four valleys between Domodossola and the Swiss frontier were under partisan control.

In London, August 23 saw another flying-bomb incident, at New Southgate, when a single bomb fell on a factory manufacturing Bailey bridges, teleprinters, tank and fighter radios, air—sea rescue launches and aircraft blind-landing gear. ‘Lie down!’ one of the factory look-outs, Reg Smith, had called over the factory loudspeakers, ‘For God’s sake, lie down’. But it was too late; 211 factory workers were killed.

***

Churchill was in Italy on August 23, when, near Siena, he visited the troops who, despite the considerable diversion of forces and weaponry to southern France, were planning a new offensive in three days’ time. That day, it was agreed by the War Cabinet in London that Jewish soldiers in the Allied armies, and above all in Palestine, could serve in a specifically Jewish fighting unit, to be known as the Jewish Brigade Group. This force, Churchill explained in a telegram that day to Roosevelt, would constitute ‘what you would call a regimental combat team’, and he added: ‘This will give great satisfaction to the Jews when it is published and surely they of all other races have the right to strike at the Germans as a recognisable body. They wish to have their own flag which is the Star of David on a white background with two light blue bars. I cannot see why this should not be done. Indeed I think that the flying of this flag at the head of a combat unit would be a message to go all over the world’.

***

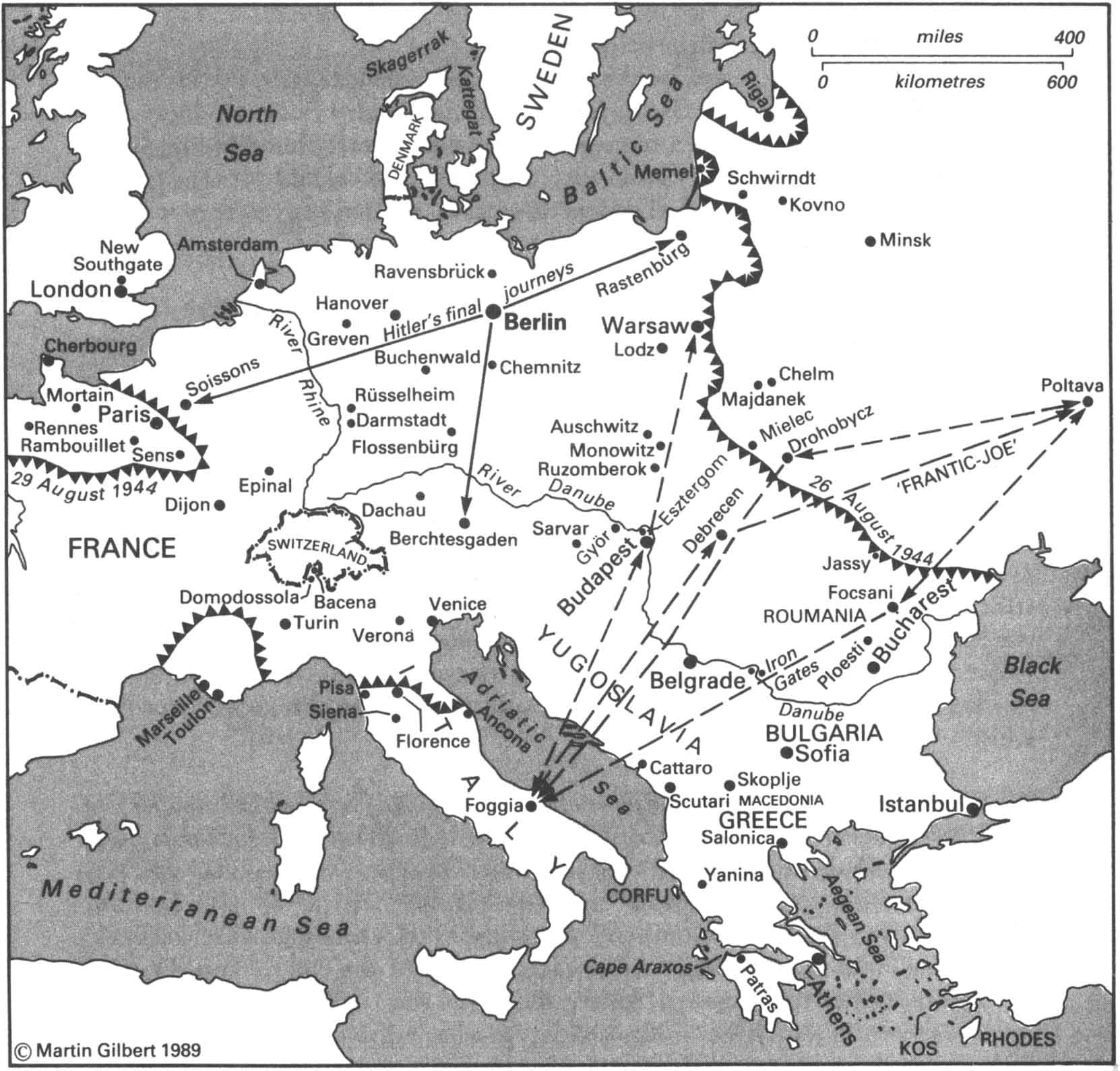

The German ability to continue the war now depended, not on the tenacity of its soldiers, but on the ability to continue to provide fuel oil for their tanks and vehicles, as well as the oil needed for every other aspect of war-making: aircraft fuel, anti-aircraft gun lubrication, and the fuel oils needed to maintain the production of arms and ammunition. Since June 8, the bombing of German oil installations had been an Anglo-American priority. At the end of July, British Intelligence learned that German fighter production was recovering; this was one more reason to intensify the oil campaign. Another reason was the knowledge reaching the Allies of a German emergency organisation which had been set up specifically to repair oil installations. Beginning on August 7, an intensified Allied oil offensive had been launched, during which, by the end of the month, sixty bombing raids had taken place, against oil targets throughout Germany and south-eastern Europe. Half of these raids were against oil storage plants, a quarter against synthetic oil plants, and a quarter against synthetic oil refineries.

That this strategy was the correct one was made clear on August 12, when British Intelligence decrypted a German Air Force Enigma message, sent two days earlier from German Air Force headquarters, ordering a general curtailment of operational activity because of further damage to German fuel production by air attacks. Reconnaissance was to be flown only when it was essential. Four-engined aircraft were to fly only after application to headquarters. Other aircraft were only to fly when action could be decisive, or when the chances of success were good. This first curtailment of German operational, as opposed to nonessential flying, was followed a few days later, on August 16, by what had been von Kluge’s last appeal to German Army headquarters, asking permission to withdraw from Falaise in view of tank deficiencies and shortage of fuel, which was in his words ‘the decisive factor’. This dramatic admission, sent by top-secret Ultra, was, as a result of its high secrecy, made known almost at once to the vigilant listeners at Bletchley.

The oil campaign, August 1944: oil targets

On August 20, four days after von Kluge’s appeal, American bombers struck at the synthetic oil plant at Monowitz. During the raid, several hundred British prisoners-of-war, as well as tens of thousands of Jewish slave labourers, watched as the bombs fell on the oil installations. During the raid, thirty-eight of the British prisoners-of-war were killed.

In a further American bombing raid on August 22, the synthetic oil plant at Blechhammer was the target; three days later, it was the synthetic oil plant at Pölitz. That same week, on August 27, British bombers carried out a daylight raid on the synthetic oil plant at Homberg, the first ever raid in which British bombers had penetrated as far as the Rhine by day. That same day, British Intelligence decrypted a German Air Force Enigma message, in which the German Air Force High Command had warned the principal air fleet on the Western Front that its fighting activities must be even further curtailed, so as to release aircraft fuel for the training of 120 air-crews a month for the Western Front. The alternative, warned the High Command, was that the existing extremely low allocation of fuel oil for training for the Western Front would have to be accepted, in which case only one-third of the replacement needs of the German Air Force in the West could be met.

***

On August 23, a French armoured division began its advance on Paris, reaching Rambouillet, thirty miles to the south west of the capital, by nightfall. During the day, Resistance forces, now established as the French Forces of the Interior under General Koenig, freed all French civilian captives in the capital.

The Germans, in one last effort to show their ability to hit back, attacked Resistance forces which had taken over the Grand Palais, and set it on fire. Elsewhere in the centre of the city, heavily armed German patrols attacked Resistance groups, killing many, and forcing others to withdraw from the streets. But this demonstration of strength came too late to influence the fate of the capital.

On the morning of August 24, a French armoured force commanded by Colonel Pierre Billotte entered the city from the south, through the Porte d’Orléans. Tens of thousands of Parisians came out to welcome their liberators with flags, food, flowers, wine and kisses. Yet still there were German strongpoints and barricades which were strongly defended; soldiers died on both sides of the barricades. Civilians died too, caught up in the cross-fire. But the delirium of liberation quickly swept aside such obstacles as remained, while the bells of Paris rang out their victory peals.

As the Germans retreated on all the war fronts, on August 24, in the slave-labour camp at Mielec, in southern Poland, the SS murdered three thousand Jewish slave labourers that day, before evacuating the camp. Three weeks earlier, two thousand Jews had been murdered in the labour camp at Ostrowiec. Also on August 24, the crew of an American bomber, shot down over Greven, as they returned from an air raid on Hanover, were taken south by train, for interrogation. On reaching the town of Rüsselheim, where the railway line had been blocked by a British bombing raid a few hours earlier, and where the streets were full of hundreds of people evacuating that part of town, they were set upon by an irate mob, beaten with clubs, rocks, bricks and stones. Six of the Americans were killed. Two survived.

The Allied bombing of Germany led to several such incidents. On August 24, in a raid on the Gustloff armament factory outside Buchenwald, bombs fell both on the factory and on the SS barracks, killing four hundred prisoners and eighty SS men. As a retaliation, the camp Commandant, SS Major Pfister, ordered the execution two weeks later of sixteen British and French officers, all of them Special Operations Executive agents who had been captured while on missions in France. All sixteen were hanged. Eleven days after the first executions, another twelve were hanged.

On August 25, Allied reconnaissance aircraft again flew over Auschwitz from their base in southern Italy. Once more their task was to photograph the Monowitz synthethic-oil plant so necessary now to the German ability to carry on the war. Once more, the camera also took pictures of Auschwitz Main Camp, of Birkenau, of the railway sidings, the gas chambers and the crematoria. One of the photographs of August 25 actually shows (in a 1960 enlargement) Jews on the way from a train to a gas chamber and crematorium, the gate of which is seen open to receive them.

A British air reconnaissance photograph, taken above Auschwitz on 25 August 1944. In it can be seen—as identified after the war—a train on the sidings (left), groups of people, two gates to the gas chamber compounds (one of them open), the roofs of two underground dressing rooms, the roofs of two gas chambers (with vents in the ceilings through which poison gas was dropped), two of the crematoria (with their high chimneys) and the huts of the women’s camp.

The Eastern Front, September–December 1944

No attempt was made to identify any of the locations or activities at Birkenau as they appeared in the photograph, even though a plan of the camp, and a full description of what went on there, had reached the British Foreign Office in London on August 22, sent by a Zionist official, Joseph Linton, who had received it from Jerusalem. It had been compiled there from the reports of the four escapees.

Not the mass-murder site at Birkenau, but the oil installations at Monowitz, were again the intended subject of the photographs, as plans for the continuing bombing of Monowitz were made, in an attempt totally to destroy Germany’s oil-producing capacity. The first bombing raid on the synthetic-oil plant had been made on August 20.

The sole purpose of the photographic reconnaissance over Auschwitz on August 25 was to look at the damage done during the raid of August 20, and to see what further repairs were being made. The result was disappointing. ‘The damage received’, the report concluded, ‘is not sufficient to interfere seriously with synthetic fuel production, and should not greatly delay completion of this part of the plant.’

***

Shortly after seven o’clock on the morning of August 25, General Jacques Philippe Leclerc, commander of the French 2nd Armoured Division, entered Paris. There was one more day of confusion: snipers firing, small groups of Germans resisting, fifty German soldiers killed trying to defend the French Foreign Office building on the Quai d’Orsay, and dozens of captured Germans being attacked after they had surrendered, including a column of prisoners who were machine gunned as they were being marched around the Arc de Triomphe.

At two thirty in the afternoon the German Commander of Paris, General von Choltitz, surrendered. An hour and a half later, General de Gaulle reached the city, making his way through a vast crowd to the Hôtel de Ville. It was a day of triumph, but at a cost; more than five hundred Resistance fighters had been killed during the liberation of the city, as well as 127 civilians. In the elation of freedom restored, many of those who had collaborated with the Germans were killed, without trial or debate.

South of Paris, as the capital rejoiced, Resistance fighters in Lyon were still struggling to liberate their city. Forty miles to the north-west of Paris, at Vernon, British troops crossed the Seine. In southern France, American troops entered Avignon. Eight hundred miles to the east, in German-controlled Slovakia, Soviet partisans commanded by Captain Velichko, seized the town of Turciansky Sv Martin, as part of a general Slovak uprising against German rule; two days later the German General commanding the region was seized, and shot. In Estonia, Soviet forces captured Tartu, breaching the German fortified line. That same day, Roumania declared war on Germany. The Axis was in disarray. But in Warsaw, where the insurgents were still fighting after three weeks and four days, Stalin still refused to allow British or American aircraft to use Soviet airstrips in an effort to increase the dwindling Allied aid. Almost in despair, Churchill telegraphed to Stalin on August 25: ‘We do not try to form an opinion about the persons who instigated this rising which was certainly called for repeatedly by Radio Moscow. Our sympathies are however for the “almost unarmed people” whose special faith has led them to attack German guns, tanks and aircraft. We cannot think that Hitler’s cruelties will end with their resistance. On the contrary it seems probable that that is the time when they will begin with full ferocity. The massacre in Warsaw will undoubtedly be a very great annoyance to us when we all meet at the end of the war. Unless you directly forbid it therefore we propose to send the planes’.

If Stalin failed to reply to this appeal, Churchill told Roosevelt, ‘I feel we ought to go, and see what happens.’ British and American aircraft would make the journey without Stalin’s approval. ‘I cannot conceive’, Churchill added, ‘that he would maltreat or detain them’.

Roosevelt rejected Churchill’s suggestion. One reason, he told Churchill on August 26, was Stalin’s ‘definite refusal’ to allow Soviet airfields to be used by Allied planes seeking to drop supplies in Warsaw. The other reason was the ‘current American conversations’ with the Soviet Union about the future use of Soviet airbases, in Siberia, for use by American bombers on their way to bomb Japan. ‘I do not consider it advantageous to the long range general war prospect’, Roosevelt explained, ‘for me to join with you in the proposed message to Uncle J.’

Thus, over aid to Warsaw, the Anglo-American unity was broken, leaving Britain alone to take, if she so wished, a step that would greatly anger the Soviet Union.

On August 28 it was learned in London and Washington that, as the Red Army advanced through Poland, leaders of the underground Polish Home Army were being arrested. On the following day, the British and American Governments issued a public declaration, that the Polish Home Army was a ‘responsible belligerent force’. The future of Poland had become the principal cause of contention among the Allies.

***

On August 26, General de Gaulle walked in triumph down the Champs Élysées. That same day, crossing the Seine over the Vernon bridgehead, Canadian and British troops advanced swiftly towards Calais and Brussels. In Italy, the British Eighth Army attacked the German defences of the Gothic Line, but, despite the capture of Pisa, a German counter-attack enabled the line to be restored, and it was to remain intact for the rest of the year.

In Berlin, August 26 saw another execution in the Plötzensee Prison; the hanging of Adam von Trott zu Solz, a German Foreign Office official who had held secret talks with British and American diplomats in Switzerland at the beginning of the year, and who, while a strong German patriot, was also an anti-Nazi; he was descended, on his mother’s side, from John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the United States.

On August 27 there was a further execution, not of German conspirators but of French civilians, seized by German troops as they retreated through the village of Chalautre-la-Petite, fifty-three miles south-east of Paris. That day, American troops had entered the nearby town of Provins, and an advance party had, briefly, entered Chalautre and then withdrawn, taking two German soldiers prisoner. The soldiers escaped, and the Germans returned to Chalautre in search of ‘partisans’. No one was found; the Americans had moved elsewhere. But the Germans took twenty-two villagers and led them out of the village; some succeeded in breaking away, but thirteen were shot. Four days later, after the Americans had liberated the village, six German prisoners, ‘donated’ by the Americans who had captured them, were shot in revenge, not by the villagers, but by people from the neighbourhood.

At his ‘Wolf’s Lair’ headquarters in East Prussia, on August 27, Hitler personally conferred the Oak Leaves to the Knight’s Cross on the Flemish fascist leader and Commander of the Walloon SS Assault brigade, Léon Degrelle. This was a rare award and a rare honour for a foreign volunteer. Only 632 of Degrelle’s two thousand volunteer troops survived the war.

On the day after Degrelle was honoured by Hitler, the former German Communist leader, Ernst Thaelmann, who in 1932 had contested with Hitler for the Presidency, was shot at Buchenwald, after more than ten years in captivity. He was fifty-eight years old. Also killed in Buchenwald that day, by Allied bombs dropped accidentally on the camp, were Princess Mafalda, the daughter of the King of Italy, and Marcel Michelin, the tyre manufacturer.

At Auschwitz, while Jews continued to be murdered inside the camp, other Jews were being sent to slave labour outside it. Simultaneously with the arrival of trains bringing Jews from the Lodz ghetto, Rhodes, Kos and Slovakia, most of whom were gassed on their arrival at Auschwitz, other trains continued to take Jews away from the barracks at Auschwitz to factories and labour camps inside Germany. On August 29, while seventy-two sick Jewish adults and youths and several pregnant women from a labour camp at Leipzig were brought to Auschwitz and gassed, 807 Jews were sent from Auschwitz to the concentration camp at Sachsenhausen, just north of Berlin, for work in a dozen nearby factories. On August 30, a further five hundred Hungarian Jews were sent by train from Auschwitz to Buchenwald, to be sent on to a Junkers aircraft factory at Markkleeberg. Other Jews were kept in Buchenwald, from where, as one young Jew from the Lodz ghetto, Michael Etkind, later recalled, ‘no one escaped. No one was missing—except the dead.’

***

On August 28, the British defences in southern England finally got the better of the flying bomb. That day, ninety-seven bombs were sent across the Channel. Thirteen were destroyed by British fighters over the water. Sixty-five were then shot down by anti-aircraft guns over land. Another ten were shot down by fighters over land. Nine reached the outskirts of London, where two collided with barrage balloons and three came to earth before reaching the capital. Only four fell on London.

That day, in southern France, Allied forces entered Toulon and Marseille, taking 47,000 German prisoners. In the north, on the following day, Reims and Châlons-sur-Marne fell to the Americans, who were now less than 110 miles from Germany’s western border. Also on August 29, British bombers flew across the whole of northern Germany, to the East Prussian city of Königsberg. For the loss of four of the 175 attackers, 134,000 citizens of Königsberg were made homeless. The city was a mere fifty-five miles from Hitler’s headquarters at Rastenburg. That same day, above Belgium, an American pilot, Major J. Myers, forced down a German jet fighter: it was a new weapon, but one which was arriving too late to alter the course of the war.

The Slovak uprising, August–October 1944

The only initiative which the Germans now seemed able to take was in the war behind the lines. On August 29, German reinforcements entered Slovakia, where they were in action against Slovak partisans at Zilina, Cadca, Povazska Bystrica and Trencin. The partisans reacted by declaring a Czechoslovak Republic and taking virtual control of the city of Banska Bystrica, as well as much of the area between Banska Bystrica and Brezno, Zvolen and Ruzomberok.

***

On August 30, Soviet forces occupied the Roumanian city of Ploesti, Germany’s only remaining source of crude oil. That day, in Berlin, General Kurt von Stuelpnagel, the former Military Governor of Paris, who, after the July Plot, had tried to commit suicide but had succeeded only in blinding himself, was led by the hand to the gallows at Plötzensee Prison, and hanged.

Broadcasting from Germany on August 30, William Joyce, who was about to be awarded the Cross of War Merit, First Class, blamed the conspirators for having kept essential troops away from the front; these conspirators, he said, ‘have paid the just penalty’. Germany was now in a position, ‘not only to defend itself, but, with the aid of time, to win this war’. The chief purpose of German strategy ‘at the moment’, said Joyce, was to gain time.

Time was not to be allowed to Germany by the ever advancing Allies: on August 31, in France, American troops crossed the Meuse at Commercy, less than sixty miles from Germany; in Italy, Canadian and British troops penetrated the Gothic Line, while American troops crossed the River Arno; in the Balkans, Bucharest fell to the Red Army. In the Pacific, August 31 saw the American capture of Numfoor Island, off the northern coast of New Guinea; during the battle, 1,730 Japanese were killed, for the loss of sixty-three American lives.

In the march to victory, success and tragedy went side by side; on August 31, as American forces in southern France drew near to the mountain village of Peira Cava, inland from Nice, twelve young men, most of them teenagers, were murdered by the SS. A memorial records their fate.

***

On September 1, the Royal Air Force and Tito’s partisans launched Operation Ratweek, a seven-day joint attack on German road and rail routes through Yugoslavia, aimed at preventing the evacuation of German troops from Greece and the Balkans. Several railway bridges on the evacuation route were totally destroyed, as were many kilometres of track. At the same time, an unexpectedly rapid advance by the Red Army to the Danube at Turnu Severin made it certain that, in conjunction with the success of Operation Ratweek, the Germans would be unable to withdraw any substantial number of troops from the Balkans to assist their troops elsewhere, either in Italy or in Central Europe.

As Ratweek disrupted all German road and rail movement northward through Yugoslavia, Greek guerrillas launched Operation Noah’s Ark, to harass 315,000 German troops who were trying to get back to Yugoslavia, particularly those on the roads into and out of Yanina. Those Germans who sought a more westerly line of retreat through Albania were no more fortunate; Albanian partisans were active along all the mountain routes leading to Scutari and Cattaro. As many as 30,000 German troops were left on the Greek islands, unable to be evacuated as Allied air and sea patrols now dominated the waters of the Aegean.

***

On September 2, in the Pacific, American aircraft based on the light carrier San Jacinto, set off on a bombing mission against a Japanese radio station on Chichijima. One of the pilots, the twenty-year-old George Bush, was on his fifty-eighth mission. When six hundred miles from Japan, his plane was shot down, and he ditched into the sea. Forty-four years later he was elected President of the United States.

***

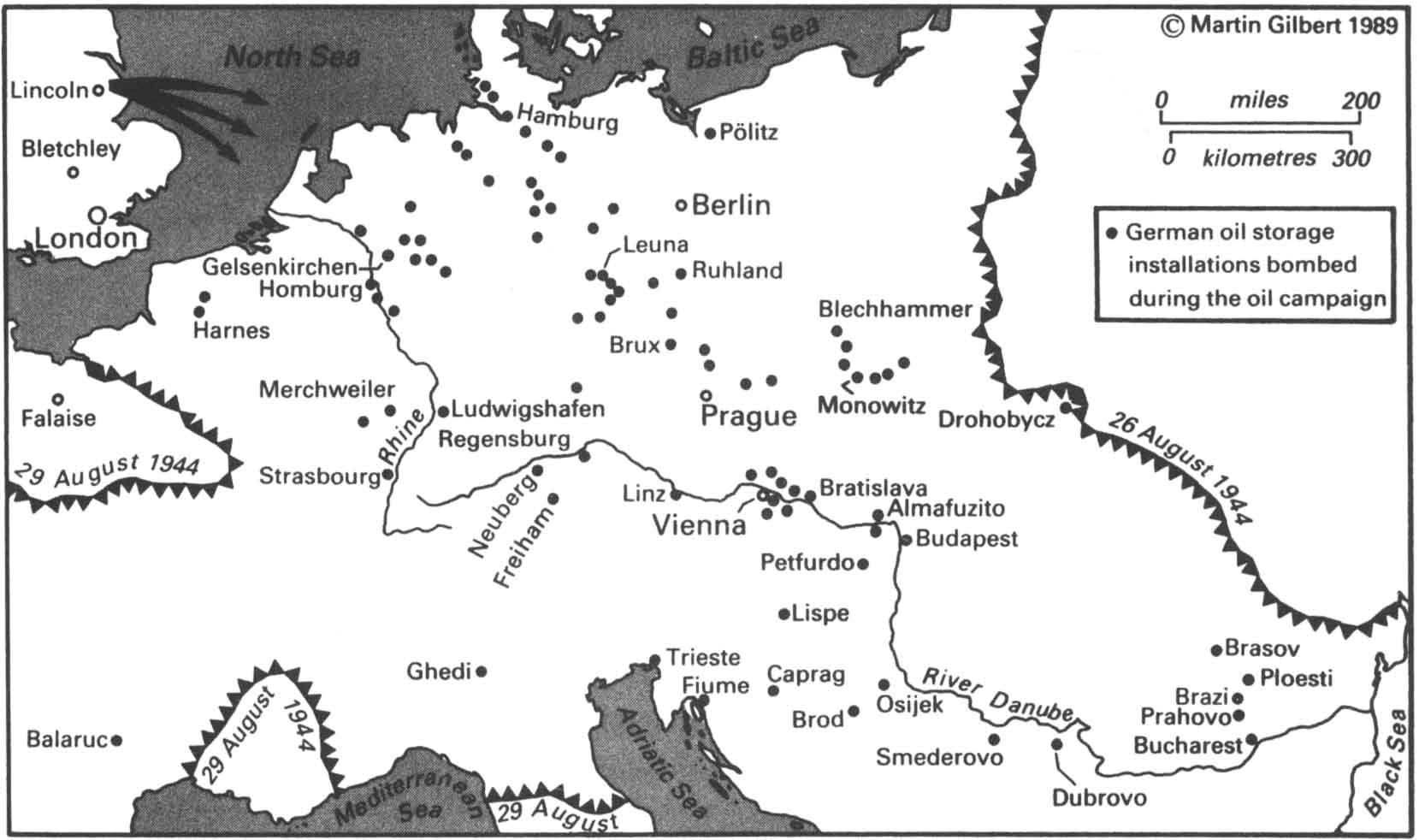

British forces crossed the border into Belgium on September 2. In Warsaw, the insurgents, after a month of fighting, were forced to abandon their positions in the Old Town, and descend into the sewers. In the village of Majorat, north-east of Warsaw, the Germans murdered more than five hundred villagers that day, including women, children and old people.

From Holland, on September 3, a thousand Jews were deported to Auschwitz, and a further 2,087 the following day. British forces, now less than two hundred miles away from the Dutch deportation camp of Westerbork, entered Brussels on September 3, the fifth anniversary of Britain’s declaration of war on Germany. On the following day, Antwerp was liberated. That same week, as a result of a suggestion first put forward by Churchill’s son Randolph, the evacuation began, by air, of 650 German, Austrian and Czech Jews from the partisan-held areas of Yugoslavia, to Allied-occupied Italy. Also in Italy, in the German-held port of Fiume, the Gestapo arrested a senior Italian police officer, Giovanni Palatucci, who had helped more than five hundred Jewish refugees who had reached Italy from Croatia, giving them ‘Aryan’ papers and sending them to safety in southern Italy. Palatucci was sent to Dachau, where he died.

On September 4, ninety Red Army officers were executed at Dachau, including the fifty-year-old Vassily Borisienko and the twenty-year-old Vassily Gajduk. September 4 also saw another execution at Plötzensee Prison in Berlin, when General Erich Fritz Fellgiebel was hanged. His task during the July Plot had been to close down the signal circuits at Rastenburg, where, as Chief of Communications for the Armed Forces, he was present at Hitler’s headquarters.

Hitler now appointed Field Marshal von Rundstedt to command the retreating German forces in the West. It was he who, in May 1940, had led the main thrust of the German armies into France. Hitler had dismissed him from his command on 2 July 1944, for failing to stop the Allied invasion of Normandy; two months later, he was again in command. But von Rundstedt saw at once how little could be done to halt the Allied armies. Watching a specially created Hitler Youth Division retreating over the Meuse, near the Belgian town of Yvoir, on September 4, he commented: ‘It is a pity that this faithful youth is sacrificed in a hopeless situation.’

Yet Hitler did not intend to give up France without a considerable fight. In a directive on September 3, which was issued to his Army commanders on the following day, he ordered Boulogne, Dunkirk and Calais to be held. In addition, by holding Walcheren Island and Breskens, at the mouth of the Scheldt, the port of Antwerp, although in Allied hands, could be made unusable for the landing of troops or supplies. ‘It must be ensured’, Hitler said, ‘that the Allies cannot use the harbour for a long time.’ The Allies were thus forced to rely on long lines of communication, stretching back to their original Normandy beach-head.

Hitler’s determination to hold on to the Scheldt was known to the Allies, through Ultra, within forty-eight hours, making clear that there was to be no speedy German retreat from Holland. But so swift had the Allied advance been so far, since the breakout from Falaise less than two weeks earlier, that the British Joint Intelligence Committee predicted, on September 5, that German resistance might end altogether by December 1, if not earlier. Churchill was sceptical of this prediction. ‘It is at least as likely’, he commented, ‘that Hitler will be fighting on 1st January as that he will collapse before then.’

Even though the Polish insurgents had been forced to abandon the Old City, Churchill still hoped to be able to drop more air supplies to those Warsaw suburbs in which the insurgents were still holding out: Zoliborz, Solec and Czerniakow. To this end he had sent two telegrams on September 4, one to Roosevelt and one to Stalin. The ‘only way’ to bring material help to the Poles, he wrote in his telegram to Roosevelt, was for American aircraft to drop supplies, ‘using Russian airfields for the purpose’, and he went on to urge the President to ‘authorize your air forces to carry out this operation, landing if necessary on Russian airfields without their consent’. Churchill’s second telegram, sent to Stalin ‘in the name of the War Cabinet’, stated that the Soviet Government’s action in preventing help from being sent to the Poles ‘seems to us at variance with the spirit of Allied co-operation to which you and we attach so much importance both for the present and for the future’.

The battle for north-west Europe, September 1944

Roosevelt’s reply was a negative one. ‘I am informed by my Office of Military Intelligence’, he wrote, ‘that the fighting Poles have departed from Warsaw and that the Germans are now in full control.’ Roosevelt added: ‘The problem of relief for the Poles in Warsaw has therefore unfortunately been solved by delay and by German action, and there now appears to be nothing we can do to assist them.’

***

On September 5, it was announced on Brussels radio, amid the euphoria of liberation, that Germany had surrendered. The news immediately spread through Britain. ‘People left their surburban homes’, the Daily Herald reported, ‘and came to town to join the celebrations. There were taxis full of singing soldiers.’

Not surrender, however, but yet another effort at intensifying the war, was Germany’s intention on September 5, when Heinkel bombers flew across the North Sea with the first of 1,200 flying bombs which they were to launch from the air. In four months, sixty-six bomber-borne flying bombs were to fall on London, but at the cost of twenty German bombers shot down, and a further twenty crashing into the North Sea as they flew to their missile-launch positions at low altitude, to avoid being detected by British coastal radar. September 5 also saw two British initiatives. The first was the intensive bombing of German dock installations and military strongpoints at Le Havre, during which the bombs started a firestorm in which 2,500 French civilians died. The second initiative was Operation Brutus, dropping the Belgian Independent Parachute Company of the Special Air Service behind the German lines, near Yvoir, to help the local Belgian Resistance.

Italian resistance was also being helped by British special forces, and had gained in both momentum and scale. On September 6, the Japanese Embassy to Mussolini’s Italy reported to Tokyo, from Venice, that although the Germans had recently achieved considerable success in their large scale punitive sweeps against Italian partisans, guerrilla activity was still increasing, especially around Turin and along the Franco-Italian frontier. This information, read by British Intelligence through Ultra, gave satisfaction to those who were in charge of the British units fighting behind German lines in Italy.

At Buchenwald, on September 6, fifteen Englishmen and Frenchmen who had been caught earlier in France helping the French Resistance were put to death. Three days later, sixteen more were summoned from the barracks, and killed. Although every day now brought liberation to several towns and villages, the execution and death of captives continued to the end.

***

On the afternoon of September 6, Soviet forces, crossing the Danube opposite the Yugoslav town of Kladovo, entered the first Yugoslav village in their path. For Tito and his partisans, now numbering tens of thousands, the time had come to liberate their own land, and to fight side by side with Soviet troops against German military strongpoints. Hitler, seeing clearly that the time could not be long distant before one or other of the Allies was on German soil, ordered an editorial in the Nazi Party newspaper, Völkischer Beobachter, which declared, on September 7: ‘Not a German stalk of wheat is to feed the enemy, not a German mouth to give him information, not a German hand to give him help. He is to find every footbridge destroyed, every road blocked—nothing but death, annihilation and hatred will meet him.’

Hitler’s adherents had no doubt as to the need to fight on to the end, and to terrorize those who stood in their path. On September 7, German troops searched a farm near the Dutch town of Middelburg, where four British evaders had been in hiding for more than four months. Three of the evaders escaped. The Germans then took four Belgians who were living on the farm, and a fifth from a neighbouring farm, drove them to the nearby sand dunes, forced them to dig their own graves in the sand, tied them to the stake, and shot them. One of those shot was a teenage boy, Yvon Colvenaer. When offered his life if he would talk, he replied that he did not want to be a traitor; before he was shot, he cried out: ‘Long live Belgium!’

***

On September 7, off the Philippine island of Mindanao, an American submarine sank a large Japanese freighter, the Shinyo Maru. Unknown to those in the submarine, there were 675 Americans on board, prisoners-of-war since the fall of the Philippines in 1942, and now being evacuated to Japan. Only eighty-five survived the sinking; swimming to the shore, they were found and sheltered by Filipino guerrillas.