The Eastern Pacific, October 1944–March 1945

On 14 October 1944, Soviet and Yugoslav forces began their assault on the German troops holding the Yugoslav capital, Belgrade. In hand-to-hand fighting, lasting for almost a week, they pressed towards the city centre. The Germans, once again determined not to yield easily, rejected a Soviet ultimatum to surrender; within forty-eight hours of this rejection, they were obliterated.

In the Arctic, Soviet forces drove the Germans from Petsamo on October 15. That same day, the Transylvanian city of Cluj was overrun after a four-day siege. Hitler now took steps to strengthen Germany’s hold over Hungary, launching Operation Mickey Mouse, the abduction of Admiral Horthy, who was seized on October 15 by troops under the command of two SS Generals, Otto Skorzeny and von dem Bach Zelewski, the latter of whom had just come from Warsaw, having crushed the last of the insurgents there. Horthy, seized in his palace in Budapest, was taken, as a prisoner, to Weilheim in Bavaria. On the following day, October 16, a pro-German government was set up by Major Szalasi, head of the fascist military organization, the Arrow Cross.

Twenty-four hours after the German Army entered Hungary, Adolf Eichmann returned to Budapest, where he at once demanded fifty thousand able-bodied Jews to be marched on foot to Germany, to serve as forced labourers there. Eichmann also wanted the remaining Jews of Budapest to be assembled in ghetto-like camps near the capital. ‘You see’, he told the Hungarian Jewish leader, Rudolf Kastner, ‘I am back again. You forgot Hungary is still in the shadow of the Reich. My arms are long and I can reach the Jews of Budapest as well.’ The Jews of Budapest, Eichmann added, ‘will be driven out on foot this time’.

These deportations began on October 20. Even as Soviet troops approached Budapest from the south-east, Jews from Budapest were marched westward, away from the advancing Soviet forces, to dig anti-tank trenches. Beginning on October 22, twenty-five thousand men and boys, and ten thousand women and girls were taken, in four days, for this task; thousands were shot as they marched, or left to die where they fell.

On October 16, the Red Army broke in force into East Prussia, advancing towards both Gumbinnen and Goldap. The roads around Hitler’s headquarters at Rastenburg were suddenly crowded with refugees fleeing westward. At Gumbinnen, the Soviet forces outnumbered the Germans by four to one, sweeping them aside. The Red Army was only fifty miles from the ‘Wolf’s Lair’.

***

On October 18, American forces in the Pacific shelled Japanese coastal defences on the island of Leyte, the first step in their most ambitious scheme yet, the reconquest of the Philippines. In Europe, German troops were seeking to crush the Slovak revolt, driving the partisans from the valleys which they had held for more than a month, and capturing Banska Bystrica, self-proclaimed capital of ‘Free Slovakia’. There was much butchery, carried out by the Dirlewanger Brigade, which less than three weeks earlier had completed the suppression of the Warsaw uprising. A hundred and twenty miles to the east of the valleys in which the slaughter was taking place, Soviet and Czechoslovak troops battled to break through the German defences in the Carpathians; in a month of fighting, twenty thousand Soviet soldiers were killed. Also killed were 6,500 members of General Ludwik Svoboda’s Czechoslovak Corps; one Czech commander, General Vedral, was only a few yards over the frontier of his native soil when he was blown up by a German mine.

On October 19, Soviet and Yugoslav forces entered Belgrade. The battle had cost fifteen thousand German dead. The Red Army and the Yugoslav partisans had also suffered heavy losses. On the following day, the Adriatic port of Dubrovnik fell to Tito’s partisans, while, inside the Hungarian frontier, a combined force of Soviet, Roumanian and Bulgarian troops, now linked in unaccustomed alliance, drove the Germans from Debrecen. Inside Germany itself, now pierced both from West and East, the Red Army captured the East Prussian border town of Eydtkuhnen, while, in the West, Aachen fell after a seven day siege. More than three thousand German soldiers were taken prisoner inside Aachen, and a further eight thousand outside it. Unit by unit, the Germans had been drawn into the defence of this, the first German city to fall into Allied hands, and to do so 1,875 days after the first German soldiers had crossed the borders of their State, in the first act of a war which, at that time, they had been so confident of winning.

On October 20, the day of Aachen’s surrender, Adolf Reichwein was tried in Berlin for his part in the July Plot. A professor of history before Hitler came to power, he had served as a link between the Kreisau Circle and resistance groups among German industrial workers. Found guilty on October 20, he was hanged that same day.

***

At five minutes past ten on October 20, in the Philippines, more than 100,000 American soldiers began to land on two separate beachheads, on the east coast of Leyte Island, near the town of Tacloban. There was much heroism; when everybody else in Private Harold Moon’s platoon had been killed, he continued to fire his machine gun for four hours, alone, killing at least eighteen Japanese before his dugout was overrun. Moon was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honour—posthumously.

For sixty-seven days the Americans fought to conquer Leyte, whose Japanese garrison of 80,000, by their prolonged resistance, forced General MacArthur to delay his planned invasion of Luzon by a further week. In all, 55,344 Japanese were killed on Leyte. Even after the island was conquered, Japanese units continued to emerge from hiding and to fight on, rather than surrender. In what were euphemistically called ‘mopping up’ operations in the first four months of 1945, a further 24,294 Japanese soldiers were killed, bringing the total Japanese death toll on the island to almost eighty thousand, virtually the whole of the original garrison. The Americans lost 3,508 men in action against the eighty thousand. It was said by the Americans who witnessed this unequal slaughter that ‘the Japanese fought to die, and the Americans fought to live’.

On October 21, on Anguar Island, in the Palaus, the Japanese garrison was overcome, after a month of fighting. In all, 1,300 Japanese soldiers were killed, as against 265 Americans. Henceforth, the Americans left the remaining islands unmolested; their Japanese garrisons, unable any longer to get supplies by air or sea, presented no danger to the American forces, who were determined to take the Philippines, and then to move on against the islands of Japan itself.

Three days after the American landings on Leyte, three separate Japanese naval forces, almost the entire Japanese fleet, sought to disrupt the landings and drive off the American warships accompanying it. Two of the first three Japanese cruisers sent against Leyte from Brunei Bay were torpedoed off the north coast of Borneo; 582 sailors were drowned, but the rest of the force continued on its way.

The greatest sea battle in history had begun. It was a battle full of carnage; when the American carrier Princeton was hit and sunk by a single bomb, more than five hundred men drowned; the loss on the cruiser Birmingham was 229. But American warplanes, unopposed, rapidly tilted the balance of destruction. When the giant 72,800 ton Japanese battleship Musashi was sunk by a massive air onslaught of thirteen aerial torpedoes and seven bombs, more than a thousand of her sailors were drowned, including her captain, Toshihei Inoguchi, who, standing on the bridge to the end, chose to go down with his ship.

After a three-day battle, thirty-six Japanese warships had been sunk, totalling 300,000 tons. The Americans lost six warships, totalling 37,000 tons. It was, Churchill telegraphed to Roosevelt, a ‘brilliant and massive victory’. It was also a turning point in the nature of Pacific warfare, with the appearance, on the last day of the battle, of a special Japanese suicide corps, the Kamikaze, or ‘divine wind’. In their first day’s work, on October 25, one kamikaze pilot drove his plane into the flight deck of the American aircraft carrier St Lo, igniting the bombs and torpedoes stored below decks. Half an hour later, the St Lo had sunk.

By the end of the war, more than five thousand kamikaze pilots had died, and thirty-four American ships sunk. But neither heroism, tenacity, skill nor suicide had been able to avert the Japanese naval disaster at Leyte Gulf, when four aircraft carriers and three battleships had been among the Japanese losses, virtually eliminating the Imperial Japanese Navy as a fighting force.

On October 25, the first day of the kamikaze attacks in Leyte Gulf, the leading Japanese air ace, Hiroyoshi Nishizawa, who had shot down eighty-seven American aircraft, died, not in combat, but as a passenger aboard a Japanese transport plane, intercepted and shot down by American fighters.

***

In western Europe, with the fall of Aachen after its virtual destruction street by street, there were those in the West who thought that the Germans might accept defeat. But Hitler’s authority, still exercised from his remote headquarters at Rastenburg, remained absolute. On October 22, the Red Army was halted at Insterburg, a mere forty-five miles from the ‘Wolf’s Lair’, by a determined German effort, while on the following day, on the Western Front, German forces held St Dié against a sustained American assault.

On October 24, in East Prussia, German troops recaptured Gumbinnen. Also on October 24, three hundred Italian Jews were deported from Bolzano to Auschwitz; 137 were gassed on arrival. On the following day, as French forces approached Strasbourg, Himmler ordered the destruction of the skeleton collection at the Anatomical Institute; a collection created as a result of the deliberate killing of Jews in Auschwitz.

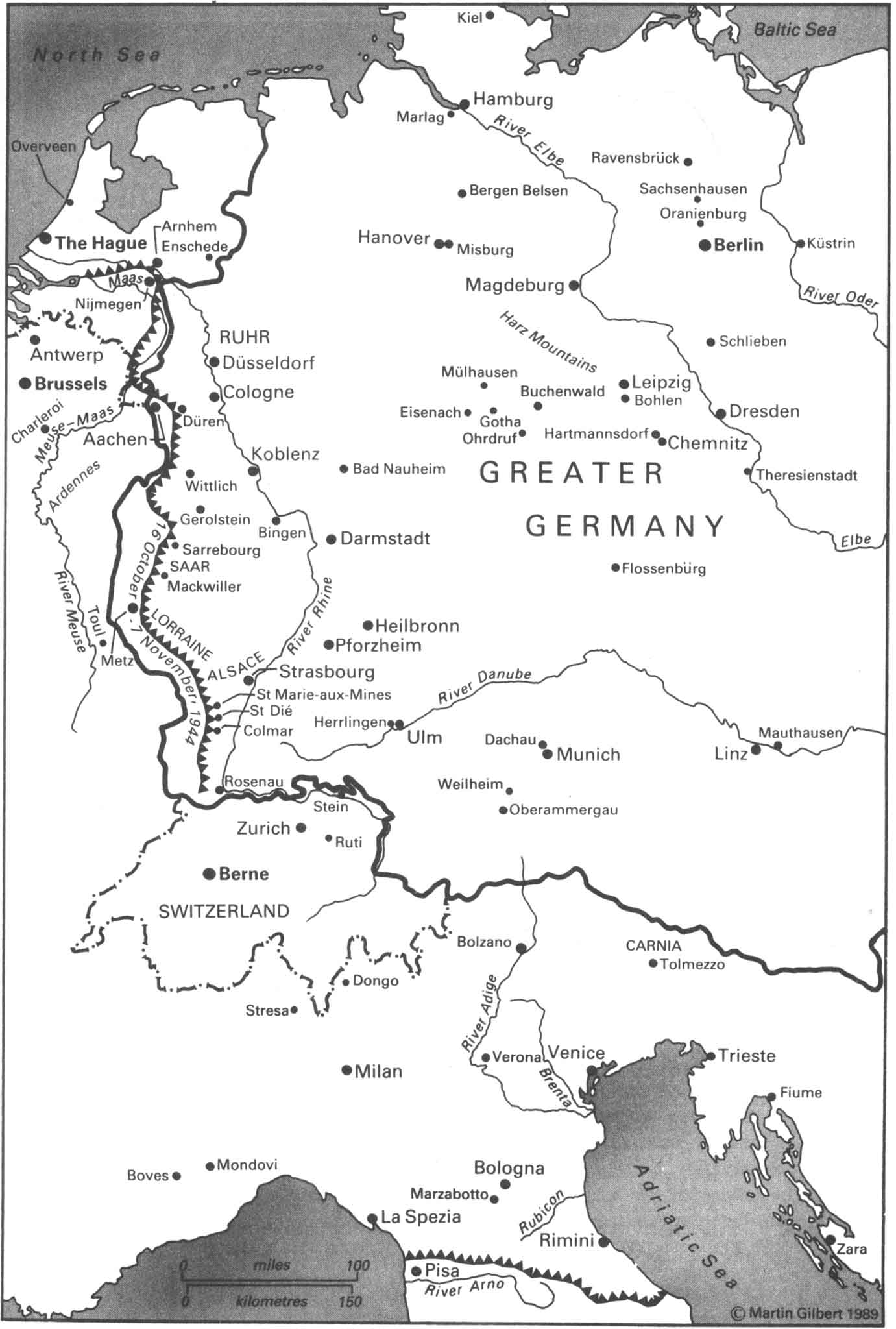

The Western and Italian fronts, October 1944

Even as the evidence of evil was being destroyed, further tests were being made of the V2 rocket. With the Allied advance into Holland, the launch unit was withdrawn northward to Overveen, on the North Sea; on October 27 it tested a rocket which rose to a height of three hundred feet before falling back on the launch crew, killing twelve of them. The launch site was then abandoned, and transferred to The Hague. On the following day, seventy-one Belgian civilians were killed in Antwerp by a flying bomb.

Also on October 28, the last deportation took place from the Theresienstadt ghetto to Auschwitz, when two thousand Jews were sent eastward; after a number of men and women were sent to the barracks, the remaining 1,689 deportees were gassed. There then followed the systematic destruction of the evidence of mass murder, with the files about individual prisoners, and the death certificates of hundreds of thousands of people, Jews and non-Jews alike, being brought to one of the two remaining crematoria and burned. All trace of the documents, as all trace of the corpses, was to be obliterated. Not only the documents and the corpses, but also the buildings of destruction were to be destroyed. When a train with more than five hundred Jews reached Auschwitz on November 3, from the Slovak labour camp at Sered, the Auschwitz administration office telephoned to Mauthausen: ‘We have a transport here; could you handle it in your gas chambers?’ The answer was, ‘That would be a waste of coal burned in the locomotive. You should be able to handle the load yourself.’

But Auschwitz no longer had the apparatus for mass murder, and on November 6 the men from Sered were given their tattoo numbers, followed on November 7 by the women and children. The men were then sent to the factory zone at Gleiwitz, the women and children to the barracks. A twelve-year-old girl who survived this Sered transport later recalled that there were about a hundred and fifty children in the transport.

***

On October 31, the Red Army crossed the River Tisza and reached the outskirts of Kecskemet, fifty miles from Budapest. But in Slovakia, 160 miles to the north, the last resistance was being crushed; at the battle of Kremnica, one of those captured by the Germans was Haviva Reik, a Palestinian Jewess who had been parachuted into Slovakia by the British, to help the uprising. Of the 2,100 Slovak partisans killed in action, 269 were Jews.

The Slovak uprising, like the Warsaw uprising, had broken out before the arrival of the Red Army; both were signs of an intense national identity, and desire for post-war independence. Both had been crushed by the Germans with ruthless severity, the Slovak uprising by SS General Gotlob Berger, an expert on the cowing of subject people and the organisation of Quisling States.

From Denmark, in mid-October, Danish resistance had appealed to London to bomb the Gestapo headquarters at Aarhus, in order to destroy the Gestapo records, which were about to be used in a drive to eliminate the Danish Resistance altogether. This involved a 900-mile round trip across the North Sea. In the raid, launched on October 31 by twenty-four British aircraft commanded by Group Captain Wykeham-Barnes, and made at roof-top height, the Gestapo headquarters was hit, and more than 150 Germans were killed. Also killed in the raid were more than twenty Danes, most of them informers. The Gestapo records were destroyed. One bomb, falling on a nearby private house, killed a Danish civilian.

The Eastern front, October 1944

During the confusion of the Aarhus raid, a number of Danes were released from the prison inside the Gestapo headquarters. Among these prisoners was Pastor Harald Sandbaek. Repeatedly tortured, he had reached the end of his tether; the raid had begun during what could well have been his final interrogation. Hardly had his interrogators fled, in terror, at the sound of the raid, than Pastor Sandbaek was buried under the rubble. Pulled clear by Danish forced labourers, he made his escape to Sweden.

***

On November 1, British and Canadian troops crossed the Scheldt in Operation Infatuate, the attempt to seize the island of Walcheren, in order to free both banks of the River Scheldt and open the port of Antwerp to Allied military transports. For eight days, as the landings proceeded, a total of ten thousand air sorties were made by rocket-firing aircraft against the remaining German positions on the island, already the object of earlier and sustained air attack. During this renewed bombardment, fifty-one British aircraft were shot down and thirty-one pilots killed. But already, on November 4, the first minesweepers had sailed the length of the Scheldt from the sea to Antwerp, and by the end of the month the first Allied shipping convoy had reached the port.

In Yugoslavia, Tito’s partisans drove the Germans from the Italian Adriatic port of Zara on November 2. That day, in Budapest, more than fifty thousand of the city’s Jews were driven westward, towards Austria. Bludgeoned, whipped and frequently shot at by their SS guards, as many as ten thousand perished during the six-day march. A further thousand, however, were saved by the determined personal intervention, even as the march was in progress, of the Swedish diplomat, Raoul Wallenberg, who had earlier extended the protection of the Swedish flag to several thousand Jews inside Budapest.

On November 4, the Red Army captured Cegled, just under forty miles from the Hungarian capital. But, from that moment, the road to Budapest was strongly defended. Nor was the advance going as swiftly on the Western Front as the Allies had hoped. In Belgium and Holland, Churchill telegraphed to Stalin on November 5, there had been ‘very hard fighting’, which had led to more than 40,000 killed and wounded. In Italy, Churchill added, ‘tremendous torrential rain’ had resulted in the sweeping away of a ‘vast number’ of bridges, so that all movement of troops and supplies was at a standstill.

The coming of winter, Hitler’s fanaticism, and German tenacity, were ensuring that the war would not be over in 1944. Yet British Intelligence knew how desperately the German war effort was under strain. On November 2, a top-secret directive issued in Berlin called for greater use of Germany’s canals and inland waterways in order to relieve pressure on the railways. This directive was decrypted at Bletchley six days later. Also in November, it was learned in Britain, from a further Ultra message, that the destruction of the German railway system had been so effective that Berlin had ordered an emergency mobilization of lorries to help maintain supply lines to the Western Front.

***

The Allies were now virtual masters of the European air; yet every raid had its element of risk. On 6 November 1944, in a raid by South African Air Force fighters against German troop trains on the Brod—Sarajevo railway line in Yugoslavia, one of the ten aircraft was shot down, and its pilot, Lieutenant R. R. Linsley, killed. That same day, in an American bombing raid on Hamburg, a much decorated American airman, Jay McDonough, from Chicago, was wounded. He already had the Air Medal with four Oak Leaf Clusters; having been wounded, he received the Purple Heart. Within six weeks, he was again in action.

On November 7, Franklin Roosevelt was elected President of the United States for a fourth term. That day, in Tokyo, one of Russia’s most successful wartime spies, Richard Sorge, was executed. He had been held in prison for more than two years. Twenty years later, he was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. In Budapest, the parachutist Hanna Szenes was executed that day by the Germans, her mission from Palestine unfulfilled, but her name a beacon for Jewish youth in the years to come. Of her fellow parachutists, Enzo Sereni was killed in Dachau eleven days later, followed on November 20, in Kremnica, by Haviva Reik, Raffi Reiss and Zvi Ben Ya’acov. Another Jewish parachutist from Palestine, Peretz Goldstein, perished in Sachsenhausen.

On November 8, Canadian forces completed the capture of Walcheren Island. That day, in northern Europe, Walther Nowotny, the fifth-ranking ace of the German Air Force, was shot down and killed. He was one of only eight pilots to win the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds. As little known as Nowotny was well known, a thirty-eight-year-old German physician, Dr Kurt Heissenmeyer, was experimenting on November 8 on four recently hanged inmates at Neuengamme. Three of those killed to help his experiments were Poles; the fourth was a Russian, Ivan Tschurkin, a former locksmith from Kalinin, who was just twenty-two years old.

***

Speaking in London on November 9, Churchill commented that the French Governor of Paris and the Belgian Burgomaster of Brussels, who were both present to hear him speak, were ‘living representatives’ of ‘the splendid events which have so recently taken place’. The Allies now stood ‘on the threshold of Germany’. But the war was not yet won: ‘supreme efforts’ had yet to be made. ‘It is always in the last lap’, Churchill warned, ‘that races are either gained or lost. The effort must be forthcoming. This is no moment to slacken.’

Reaching Antwerp by air from Paris on November 10, an American officer, Brigadier General Clare H. Armstrong, set up an Anti Flying Bomb Command consisting of several thousand American, British and Polish troops, with six hundred anti-aircraft guns and a communication system designed to spot the bombs as far from the city as possible. At least half, and at times three-quarters, of the flying bombs which came over Antwerp were thus to be shot down; against the faster-than-sound V2 rocket there was, however, no possible anti-aircraft defence. Of these Allied defenders of Antwerp, thirty-two were killed while at their posts.

For many weeks, the German army had been infiltrating spies across the American lines, in an attempt to ascertain as best they could the strengths of the Allied positions. All of these infiltrators were caught. Among them were two Poles, Josef Wende and Stefan Kotas, both of whom had earlier been drafted into the German army and forced to serve as spies. Wende and Kotas had crossed the front line in civilian clothes, posing as Polish slave labourers working as coal miners. Their mission was to observe the strengths of certain American units and to return that same day with their report. After being caught, both men were tried and sentenced to death. They were executed by an American firing squad at Toul on November 11.

That same November 11, the day of the First World War armistice in 1918, Winston Churchill and Charles de Gaulle drove together through Paris to the Arc de Triomphe, where both men laid a wreath to the Unknown Soldier of that first of the century’s world wars. On the following day, in the remote Norwegian inlet of Tromsö Fjord, above the Arctic Circle, thirty-two British bombers, operating from Lossiemouth in Scotland, attacked the Tirpitz, Germany’s last surviving battleship.

If the Tirpitz could be sunk, the big ships of the British Home Fleet could at last be released to the Pacific.

Each of the British bombers carried a single, 12,000 pound ‘Tallboy’ bomb. At least two bombs hit the ship, which capsized. Of her crew of 1,800, just over eight hundred were rescued, eighty-two of them when a hole was cut in the exposed underside of the ship thirty hours after it had capsized; in all, a thousand men had drowned.

As the Tirpitz capsized, many of the men inside were heard singing the German national anthem, ‘Deutschland über Alles’. ‘What a tragedy it was’, commented the British scientist R. V. Jones, ‘that men like that had to serve the Nazi cause.’

One German who had refused to serve the Nazi cause, Bernard Letterhaus, a former Catholic labour leader, was sentenced to death on November 13, for his part in the July Plot; he was hanged on the following day.

***

On November 14, the Japanese destroyer Ushio, the last surviving warship of those which had struck at Pearl Harbour, was among the ships attacked by American aircraft in Manila Bay. Severely damaged by a bomb, she was never to be in action again. Also on November 14, in the Balkans, Bulgarian and Yugoslav troops entered Skoplje. Germany’s three-and-a-half year control of the Balkans was over. In Scandinavia, German rule was also under threat, with the landing of a Norwegian Army officer, Colonel Arne Dahl, north of the Arctic Circle, to work with Soviet forces in Karelia against the Germans, who had already been forced to abandon the port of Kirkenes and withdraw westward.

In northern Italy, a German sweep against more than a thousand partisans near Mondovi was unsuccessful; the partisans escaped the net, although their British liaison officer, Captain Neville Temple, was killed in a car accident on November 15, during the escape. He had been parachuted into the area three months earlier, as head of the ‘Flap’ mission, to attack German troops and supply convoys on the move.

On the Italian front, the Germans were holding firm to their line south of La Spezia and Bologna; repeated Allied efforts to dislodge them had failed. In Western Europe, slow but steady advances were being made both north and east of Aachen, and against Alsace and Lorraine. From behind their ever diminishing lines, the Germans were still able to send flying bombs against Antwerp; on November 16, a total of 263 civilians were killed when ten flying bombs hit the city; thirty-two of the deaths were in an orphanage which had been converted into an emergency hospital. On the following day, thirty-two nuns died when a flying bomb hit their convent.

***

In the Far East, November 17 saw a further Japanese advance into mainland China, towards Kweiyang. But that same day, in the Yellow Sea, an American submarine sank one of Japan’s few remaining escort carriers, the Jinyo, while, in Tokyo, unknown to the Americans, a secret meeting of atomic scientists heard a report that ‘since February of this year there has not been a great deal of progress’. It had become clear, those at the meeting realized, that Japan could not build an atomic bomb in time to affect the outcome of the war.

From the eastern frontiers of India, the British, now masters of Imphal and Kohima, launched Operation Extended Capital on November 19, to drive into Burma on a wide front; within two weeks, the Chindwin river had been crossed at three separate points. In Western Europe, French forces reached the Rhine on November 19, at Rosenau, near the border of France and Switzerland. Further north, the Germans were rapidly being driven from Alsace and Lorraine, losing Sarrebourg on November 20. That day, Hitler left Rastenburg for Berlin. He was never to see East Prussia again.

On the day that Hitler returned to his capital, a man who had helped to impose the worst evils of Nazism on the captive peoples of Europe was being brought to trial; he was a Belgian collaborator, Fernand Daumeries. Tried at Charleroi on November 20 for inhumane behaviour at Breendonk camp, on the outskirts of Antwerp, Daumeries was sentenced to death.

On November 22, American troops entered the town of St Dié, in the foothills of the Vosges; it was in flames, having been set on fire by the retreating Germans. ‘For the second time in twenty-five years,’ an emotional Mayor Evrat told his liberators, ‘our brave American friends have come to the rescue of their grandmother, aged Europe, and of their godmother, the city of St Dié.’

During the First World War, for four years, St Dié had been less than ten miles from the German front line.

On November 23, French and American troops entered Strasbourg, which in 1940 the Germans had made the capital of annexed Alsace. Reaching the Reich Anatomical Institute of Himmler’s friend Professor Auguste Hirt, the Americans found a supply of headless bodies in his storeroom. The Professor himself had disappeared, and was never found. He was forty-six years old.

On November 25, the city of Metz fell to General Patton’s Third Army. That day, at Auschwitz, the Germans began the demolition of the remaining gas chambers. On the following day, all two hundred Jews who had been forced to drag the corpses into the crematoria were themselves murdered. ‘I am going away calmly,’ one of them, Chaim Herman, had written three weeks earlier to his wife and daughter in France, ‘knowing that you are alive, and our enemy is broken.’

***

In the Far East, the Allied armies were still a long way from victory. On November 24, Japanese troops entered the Chinese city of Nanning, only 120 miles by rail from their forces in French Indo-China. On the following day, in the Gulf of Leyte, every available Japanese aircraft was sent against the Americans, many of them on suicide missions, in the first of a series of hopeless yet damaging attacks. In this first attack, three aircraft carriers were damaged; on board the Intrepid, sixty-five men were killed.

Over London, on November 25, a V2 rocket hit a Woolworth’s department store in New Cross Road, Deptford, killing 160 lunchtime shoppers. ‘I remember seeing a horse’s head in the gutter,’ a thirteen-year-old girl, June Gaida, later recalled, and she added: ‘Further on there was a pram all twisted and bent, and there was a little baby’s hand still in its woolly sleeve. Outside the pub, there was a bus and it had been concertinaed, with rows of people sitting inside, all covered in dust—and dead.’

On the day of the Deptford rocket bomb, a British submarine, HMS Sturdy, on its way from Australia to Indonesian waters, stopped a Japanese cargo ship by surface shellfire. The Japanese crew having abandoned their ship, the only people left on board were fifty women and children, all of them Indonesians. In order to deny the Japanese any use of the ship’s cargo, the submarine commander ordered the ship to be sunk, despite a protest from the officer who had to lay the explosive charges. ‘Get on with it’, was the commander’s response. The cargo ship and its passengers were then blown up, together with the ship’s war supplies.

***

On November 26, the first Allied shipping convoy sailed through the Scheldt unimpeded to Antwerp. That day, Hitler put Heinrich Himmler in full military command of all German troops, as well as all German air forces, on the Upper Rhine. On November 27, at Auschwitz, nearly six hundred of Himmler’s men, the camp SS guard, were decorated with the Iron Cross for their ‘bravery’ in suppressing the slave labourers’ revolt of the previous month, in which four SS had been killed.

In Antwerp, the full brunt of the V2 rockets was now being felt; on November 27, when one of the rockets fell at a busy road junction near the central railway station, just as a military convoy was passing, 157 people were killed, including twenty-nine Allied servicemen from the convoy. That same day, in Britain, at Fauld in Staffordshire, an accidental explosion in an underground bomb store, in a gypsum mine ninety feet below the surface, killed sixty-eight civilians in the farms and factories above. German propaganda at once claimed that the explosion was the work of saboteurs. For their part in the rescue work, three men were awarded the George Medal.

***

On November 29, German troops in Albania abandoned the port of Scutari, falling back to a new defensive line through Mostar and Visegrad to the River Drina. In Hungary, the Red Army entered the southern cities of Pecs and Mohacs. Across the Atlantic Ocean, two German agents, Eric Gimpel and William Colepough, were landed that day on the coast of Maine, at Crabtree Neck, by German submarine. Colepough, a former sailor, had with him 60,000 dollars to pay for espionage activities. Both men were arrested within the month, their mission having been given away by Ultra even before they were put ashore.

In Berlin, on November 30, there were still further executions as a result of the failure of the July Plot; that day Lilo Gloeden, a forty-one-year-old housewife who had given shelter for six weeks to one of the plotters, General Fritz Lindemann, was beheaded with an axe, as were her husband and her mother, at two-minute intervals. Their fate was then publicized, as a warning to anyone else who might try to shelter the enemies of the Third Reich.

The fate of that Reich could not, however, be seriously in doubt. On the day of Lilo Gloeden’s execution, American troops drove the Germans from Mackwiller, in the Saar, inside Germany’s pre-war frontier. In Hungary, the Red Army entered Eger, less than twenty-five miles from the central Slovak frontier. Despite these advances, no mile of territory was yielded by the Germans without a severe fight, often from house to house.

***

On December 1, as the Jewish slave labourers in the barracks at Auschwitz-Birkenau were being evacuated by foot and train to factories and camps in western and central Germany, Josef Kramer, the Commandant at Birkenau, was himself transferred westward, to Belsen. Although there were no gas chambers in his new camp, he was determined not to do anything there which might lengthen by a single day the lives of those who were dying of starvation or disease.

The camp at Belsen was less than two hundred miles from Germany’s western frontier, and from the River Maas, along whose western bank the Allies now stood. The American commanders were confident that they could continue with their advance into Germany; on December 2, General Eisenhower noted that the American forces were destroying about three-quarters of a German division every day on the long battle front. ‘This,’ he noted, ‘is about twenty a month.’ But Hitler had plans to retake the initiative, by driving westward through the Ardennes, to Antwerp, now reopened as a principal port for Allied supplies.

Usually so alert to each impending German move, British Intelligence failed to foresee the Ardennes offensive. Yet the Enigma decrypts since mid-November had suggested some unusual German preparations in the North European war zone. There had, for example, been a number of Enigma indications of a movement of German troops westward across the Rhine and their subsequent concentration on the western side. There had also been indications of an impending large-scale air attack.

These indications, arriving over a prolonged period, were not, however satisfactorily brought together, partly because the German troop movements thus revealed were seen as an attempt to meet an impending Allied attack, and partly because those who interpreted them did not feel that the Germans were any longer capable of a serious counter-attack. Churchill was not convinced, asking the Joint Intelligence Committee, on December 3, if there was ‘any further news’. He was told that nothing was amiss. That same day, Montgomery’s chief Intelligence Officer, Brigadier Williams, commented on the most recent decrypt that the Germans’ ‘bruited sweep to Antwerp is clearly beyond his powers’.

The principal effort to cripple Germany’s warmaking powers remained the persistent and sustained attacks on synthetic oil factories and oil storage depots. On December 3, the Japanese Naval Attaché in Berlin reported to Tokyo that the transfer of German oil plants to underground locations was ‘very much behind schedule’ despite strenuous effort, and that although aircraft production was good, the fighter aircrews were losing many opportunities for combat on account of oil shortage.’

British Intelligence decrypted this message five days after it was sent. Also decrypted in mid-December was a top-secret telegram sent to Tokyo from the Japanese Ambassador in Berlin, dated December 6, with the information that the oil repair squads now employed 72,000 workers, that oil production underground was unlikely to start before March; and that total German output was running at only 300,000 tons a month. ‘Oil’, the Ambassador added, ‘was clearly Germany’s greatest worry’.

Despite the emphasis on attacking oil targets, December 4 saw, at the insistence of the head of Bomber Command, Sir Arthur Harris, a renewal of the British fire bomb attacks on German cities, when more than two thousand tons of incendiary bombs were dropped on Heilbronn. ‘We estimated that there were some two hundred planes,’ a British prisoner-of-war in a nearby camp later recalled, and he added: ‘They came circling over, wave upon wave, black shadows gliding across the floodlit ceiling, releasing their hissing bombs and slowly veering away. The flames were replenished from time to time and the countryside for miles around was flooded with yellow light. Windows could be heard tinkling to the ground all over the camp. I was in the slit trenches. A plane screamed to earth in the east’.

During the Heilbronn firestorm, 7,147 German civilians were killed.

***

On the Eastern Front, Soviet forces, avoiding the strongly fortified region around Budapest, cut off the city in the north, and, shortly before midnight on December 4, began crossing the Danube at Vac, a mere fifteen miles from Hungary’s pre-war northern border with Czechoslovakia. Three days later, Soviet forces driving from the south reached Lake Balaton, occupying the town of Adony, twenty-five miles south of Budapest. The Hungarian capital, now a German stronghold, was almost entirely cut off from the rest of Hungary. Hitler, determined not to yield this former royal city of the Austro-Hungarian Empire into which he had been born, ordered German troop reinforcements both from Italy and from the Western Front.

In the Pacific, the American fleet off Leyte had continued to be beset by Japanese suicide pilots. On December 7, the third anniversary of Pearl Harbour and of America’s entry into the war, a kamikaze pilot struck just above the waterline of the destroyer transport Ward, which, in the first American engagement of the war, had sunk a Japanese midget submarine three years earlier. Now she too was doomed; so badly damaged that she had to be sunk by naval gunfire. The commander of the ship which sank her was, by a strange coincidence, the man who had been her commanding officer in December 1941. No lives were lost. But on board the destroyer Mahan, also hit by a kamikaze pilot, ten men were killed, before she too had to be sunk.

In further suicide attacks, Japanese pilots killed thirty-six men on the carrier Cabot, thirty-one on the battleship Maryland and thirty-two on the destroyer Aulick. So heavy and continuous were these casualties, that General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz ordered a complete news blackout, with the twofold aim of preventing panic in the United States and of denying to the Japanese commanders any knowledge of the scale of damage and loss of life which their suicide pilots were inflicting.

***

On December 10, Hitler left Berlin for the Western Front, returning to the ‘Eagle’s Nest’ bunker at Bad Nauheim, a bunker which he had last used in the triumphant days of 1940. There, that same afternoon, he spoke to his senior generals about the coming offensive against the Ardennes. He also spoke, that week, to Hitler Youth leaders who had been brought to hear him from throughout the war zone. ‘Never since the Napoleonic wars’, Hitler told them, ‘has an enemy devasted our country, and we shall decimate this enemy also at the very gates to the Fatherland.’ It was on the Western Front, he declared, ‘where we are going to turn the tide and split the American—British alliance once and for all’.

Hitler was also in a reflective mood. In a further speech to his generals on December 12, he told them: ‘You can’t extract enthusiasm and self-sacrifice like something tangible, and bottle and preserve them. They are generated just once in course of a revolution, and will gradually die away. The greyness of day and the conveniences of life will then take hold on men again and turn them into solid citizens in grey flannel suits’.

That day, American forces entered the German town of Düren, twenty miles east of Aachen, and less than twenty-five miles from Cologne.

***

On December 12, in the Pacific, an American battle fleet and invasion force left Leyte Gulf on its 350 mile sea voyage to the island of Mindoro. On the following day, Japanese suicide pilots struck again. Their first target was the cruiser Nashville, on which 131 men were killed. Two hours later, the destroyer Haraden was hit, and fourteen sailors killed. Reaching Mindoro, the landing itself was a success, but on the following day, in a ferocious storm, with ninety-mile an hour winds and seventy-five foot waves, three destroyers capsized. On the Spence, 280 men were drowned; on the Hull, 195; and on the Monaghan, 244: a total death toll of 719 men, the victims of nature’s fury.

As American forces fought their way ashore on Mindoro, many thousand American, Dutch and British prisoners-of-war were being taken by ship from the Philippines to Japan. The conditions on these ships were appalling. On board the Oryoku Maru, 40 of the 1,650 prisoners died in forty-eight hours. Locked below decks, and allowed only one canteen of water for every thirty-five men, some drank urine to try to assuage their thirst, others cut themselves so as to be able to moisten their lips with their own blood. Many hundreds went mad. Then, when the ship was sunk by an American aeroplane on December 15, and more than a thousand prisoners-of-war were in the water, the Japanese opened fire on them with machine guns. Two hundred were killed during the sinking and the shooting. More than a thousand of the survivors died later, when a ship to which they had been transferred, the Enoura Maru, was bombed in Takao harbour, in Formosa. Of the 1,650 who had set off, only 450 eventually reached Japan.

On the Philippine island of Palawan, 150 American prisoners-of-war in a camp at Puerto Princesa were ordered into deep air raid shelters on December 14, warned by their Japanese captors that an American air raid was on its way. The warning was a trick. As soon as the men were in the shelters, more than fifty Japanese soldiers attacked them, throwing in buckets full of petrol and then lighted torches. As the Americans fled, burning, from the shelters, they were shot, bayoneted and clubbed to death. Badly burned men, some moaning in agony, were buried alive. Only five survived.

***

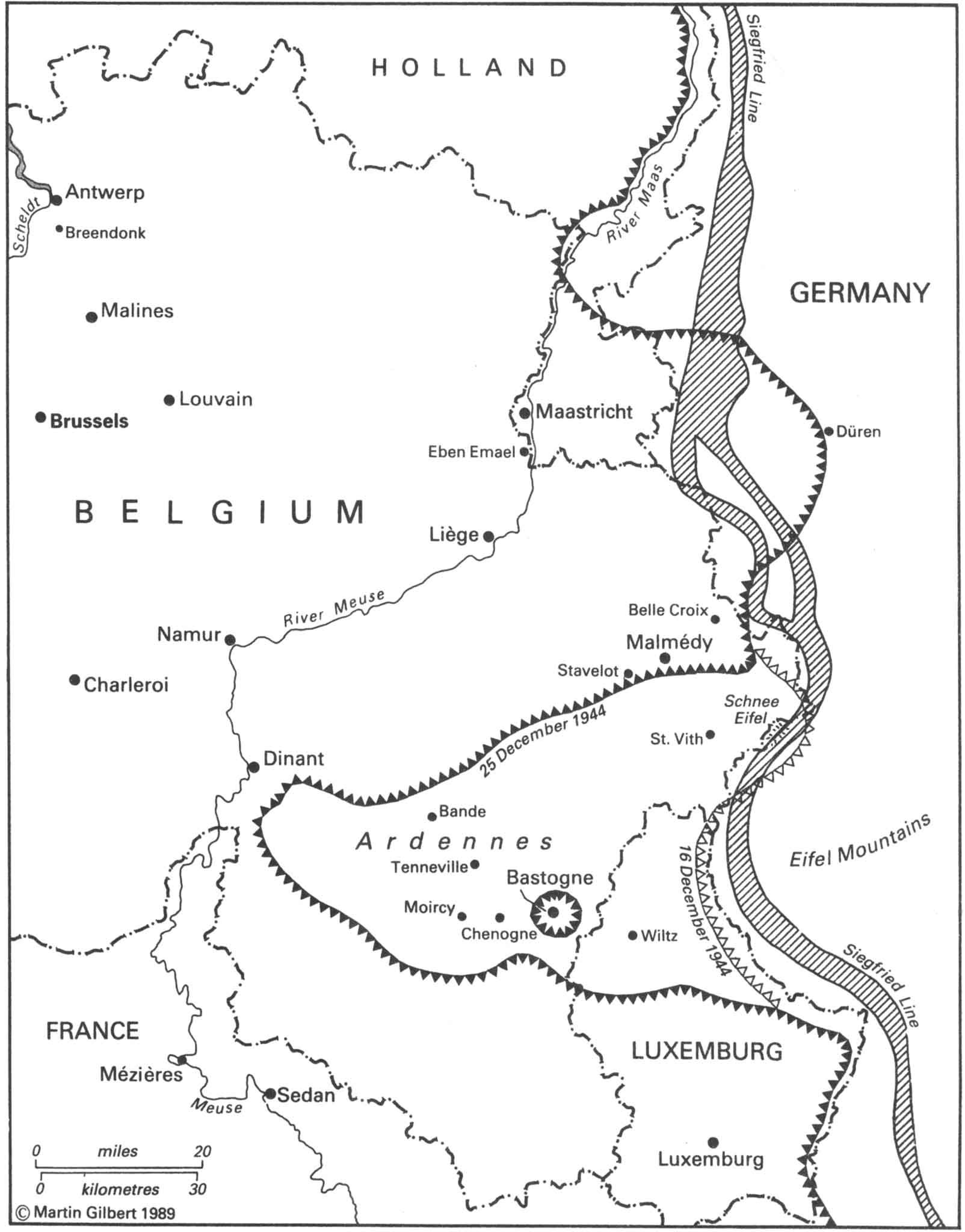

On December 16, the German Army launched its counter-offensive, Operation Autumn Mist, against the Allied forces in the Ardennes, seeking to push the Allied line back through Belgium to Antwerp and the River Scheldt. A German attempt on the previous night to drop parachute troops in the rear, near Belle Croix, to disrupt Allied communications at the moment of the attack was, however, a failure; within twenty-four hours, most of the paratroops had been captured, without causing any disruption.

In all, a quarter of a million German soldiers were thrown into the Ardennes assault. Opposite them were 80,000 men, unprepared for an attack, let alone such a massive one. At Hitler’s suggestion, thirty-three English-speaking German commandos, led by Otto Skorzeny, infiltrated through the Allied lines dressed in American uniforms and driving captured American jeeps and trucks. They were able to cause considerable confusion and, once the trick was discovered, a frenzy of suspicion. ‘Three times I was ordered to prove my identity by cautious GIs,’ General Bradley later recalled. ‘The first time by identifying Springfield as the capital of Illinois (my questioner held out for Chicago); the second by locating the guard between the centre and tackle on a line of scrimmage; the third time by naming the then current spouse of a blonde named Betty Grable. Grable stopped me, but the sentry did not. Pleased at having stumped me, he nevertheless passed me on’.

The German counter-offensive in the Ardennes, December 1944

For ten days the Germans drove forward. At one point in the battle, at the Schnee Eifel, nearly nine thousand Americans, surrounded, outnumbered and outgunned, surrendered; after Bataan, this was the largest single mass surrender in American history. More than nineteen thousand Americans were killed in the battle, as were forty thousand Germans.

On the first day of the Ardennes offensive, disaster struck Antwerp, when a V-2 rocket hit a cinema, killing 567 people; 296 of them were Allied servicemen. The rocket had been fired from near Enschede, in Holland, 130 miles away. There was a slaughter of another sort on the following day, December 17, when seventy-two American soldiers, having been captured by a German SS unit south of the Ardennes town of Malmédy, were led into an open field, lined up, and machine-gunned. About twelve of the men managed to escape the massacre and hide in a café. The Germans surrounded the café, set it on fire, and then shot the men as they fled from the flames.

The news of the Malmédy massacre spread rapidly through the battlefield. After the surprise and panic of the first German attack, the Americans quickly found a sterner mood, with ‘Avenge Malmédy’ as its cry. There were also several other massacres by the same SS unit: at ten other places along its line of march, at least 308 American soldiers and 111 Belgian civilians were killed after being captured or arrested.

The commander of the SS unit which carried out these killings was SS Lieutenant-Colonel Joachim Peiper. For his work in November 1943, during an action against Soviet partisans near Zhitomir, Peiper had received the Oak Leaves to his Knight’s Cross. During that particular sweep, an estimated 2,500 Russians had been killed, and only three taken prisoner.

The German murderers in the Ardennes were mostly soldiers in their early twenties. Their whole upbringing and education had been in the Hitler Youth. They were imbued with the SS belief that mercy was a crime. On December 19, near Stavelot, they killed 130 Belgian civilians; forty-seven women, twenty-three children and sixty men, whom they systematically executed on the charge of sheltering American soldiers. When one of the villagers appealed to Peiper to stop the killing, he replied: ‘All you people in this region are terrorists.’

The atrocities committed in the Ardennes were parallelled and surpassed by those taking place in the Philipinnes, where Japanese soldiers acted with terrible brutality towards the Filipinos. ‘Taking advantage of darkness’, a Japanese private noted in his diary on December 19, ‘we went out to kill the natives. It was hard for me to kill them because they seemed to be good people. The frightful cries of the women and children were horrible.’ ‘I myself,’ the soldier added, ‘killed several persons.’

On December 20, the German forces in the Ardennes surrounded the town of Bastogne, trapping several thousand American soldiers. That same day, in Berlin, the German industrialist Caesar von Hofacker was executed for complicity in the July Plot. He was one of those who, on July 16, had made the final decision to kill Hitler—four days before the actual assassination attempt.

As the battle in the Ardennes continued, the repercussions of the Malmédy massacre were quickly felt. On December 21, at Chenogne, as German soldiers emerged from a burning house carrying a Red Cross flag, they were shot down in the doorway; twenty-one were killed.

In Antwerp, sixteen people were killed on December 21 when a V2 rocket hit a hospital; on the following day, at almost exactly the same spot, three Belgian workmen were killed by a second rocket, as they were clearing the rubble created by the first.

In all, 3,752 Belgian civilians were killed by V2 rockets in Antwerp that winter. In addition, 731 Allied servicemen were killed by the rockets on Antwerp. Not occupation, but liberation, had brought death to the city’s streets.

***

On December 18, American bombers had struck again at the German synthetic oil factory at Monowitz. Three days later, a South African photographic reconnaissance aircraft flew over the factory. Its sole aim was to photograph the damage done to the oil-producing system, but once again, within the full frame of one of the photographs, many of the electrified fences and guard towers of Auschwitz—Birkenau can be seen to have been dismantled.

All gassing at Auschwitz had now ceased, but Auschwitz Main Camp remained, as did the camp for Jewish women in Birkenau: in December, more than 20,000 women were being held captive there.

***

In strictest secrecy, December 21 saw the award of the MBE—Member of the British Empire—to Germany’s leading spy in Britain, Jean Pujol Garcia, the German agent ‘Arabel’ who, as ‘Garbo’, had served British Intelligence for more than two years, including the D-Day deception plan. The presentation was made, not at Buckingham Palace, where secrecy might well have been difficult to maintain, but at the headquarters of the Security Services, where a short speech of appreciation was made to Garcia by the head of the Service.

***

On December 22, despite the German success, so far, in the Ardennes, Field Marshal von Rundstedt asked Hitler to authorize a withdrawal to the Eifel Mountains. Hitler refused. Behind the American lines in the Ardennes, Otto Skorzeny was still causing havoc with his teams of English-speaking commandos around the still American-held town of Malmédy, causing considerable damage, blowing up bridges and embankments, and adding to the discomfort of the Americans. Hitler’s faith in the offensive remained. But when, that same day, the Germans called on Major-General Anthony McAuliffe, the American commander besieged in Bastogne, to surrender, they received a single word answer: ‘Nuts!’ Asked what this answer meant, they were told, with scarcely less brevity, that its meaning was: ‘Go to hell.’

On December 22, General Eisenhower issued an Order of the Day to all Allied troops in the Ardennes. ‘Let everyone hold before him a single thought’, he said, ‘to destroy the enemy on the ground, in the air, everywhere to destroy him.’ In fact, Allied operations in the air had been virtually impossible since the Ardennes offensive had begun, because of low lying fog; the fog only cleared on December 23. But once it cleared, Allied air superiority was quickly established; hardly a single German train, vehicle or group of soldiers could move without being seen and attacked. Bastogne, too, could now be supplied by air, effectively ending the perils, if not the geography, of the siege.

With the lifting of the fog, Allied bombers struck at the German railway stations through which supplies would have to come: the railway yards at Koblenz, Gerolstein and Bingen were attacked until they were unusable. At the same time, Allied fighters could now follow clearly the line of advance of the most forward German tanks, as they reached to within five miles of the River Meuse. Not only could these tank formations now be attacked from the air, but, even more inhibiting, they had begun to run out of fuel. British bombers having now joined the American oil offensive, the Germans had not been able to accumulate enough oil to maintain a sustained offensive. German air cover was likewise of little avail to them; on December 23 the German Air Force commander for the offensive, General Peltz, was complaining that his pilots were breaking off their attacks without good reason, jettisoning their extra fuel tanks, and heading back to Germany. That day, twenty per cent of one squadron’s aircraft had turned back in this way.

On December 23, American forces launched their first counter-attack against the southern flank of the Ardennes ‘bulge’. That day, three of Skorzeny’s commandos, who had been captured wearing their American uniforms, were shot by an American firing squad. Fifteen other commandos later suffered the same fate. Fifteen returned to Germany.

At midday on December 24, sixteen German jet aircraft, known as ‘Blitz’ bombers, were in operation against a ball-bearing factory and tool-die warehouse in Liège. They then flew on to attack railway marshalling yards supplying the Allied forces in the Ardennes. It was the first jet bomber operation in history.

By Christmas Eve, the German offensive towards Antwerp had been halted; after an advance of less than sixty miles, at its furthest point, it had nowhere reached closer than seventy miles to its objective, although coming close to the Meuse. On Christmas Eve, in the Ardennes village of Bande, a Gestapo unit, calling itself the ‘Special Himmler Troops’, shot thirty-two Belgians; thirty as a reprisal for three Germans killed three months earlier by the Belgian Resistance, and two in reprisal for the killing of a Belgian collaborator.

There were many other murders that Christmas Eve; a British prisoner-of-war, Corporal Rowley, recalled one such killing in his prisoner-of-war camp at Hartmannsdorf. ‘I was in the compound’, he wrote, ‘when I saw two German guards carry the dead body of a Russian POW into the camp and dump the body on the floor of the wash house. I asked the Russian interpreter what he was going to do about it and he said “leave well alone”. I went into the wash house and examined the body. He had been shot through the chest. There was also a bullet embedded in his elbow; it appeared that he had been shot by a drunken guard’.

Also on Christmas Eve, the Germans launched a final flying bomb attack on England. As well as warheads, the bombs contained letters from British prisoners-of-war; these letters were scattered like confetti when the bombs exploded. ‘Dearest,’ read one of them, ‘This is an unexpected and extra letter card that we have been permitted to send off with our Xmas greetings.’

One of these Christmas Eve flying bombs hit a workers’ hut near Gravesend, killing all twelve of its occupants. At Oldham, twenty-eight people were killed, including a woman of seventy-nine and a six-month-old child. These were the last large-scale deaths caused by a flying bomb in Britain.

***

On Christmas Day 1944, the first irradiated slugs of uranium were turned out by a reactor at the atomic research centre at Hanford, in the United States, and, a month later, the first plutonium was ready for shipment. The atomic bomb was even nearer to becoming a reality.

***

In Greece, the arrangement which Churchill had made with Stalin two months earlier, that this would be the one Balkan country not to come within the Soviet sphere of influence, seemed about to be breached. Greek Communist forces, hitherto active as an anti-German guerrilla movement, were, that Christmas, in partial control of Athens itself. Churchill, in a dramatic move, flew to Athens, where, on December 25, amid sniper fire and the threat of an imminent Communist take-over of the city, he prevailed upon the Greek Communist leaders to join the Government of the Regent, Archbishop Damaskinos. The Soviet representative at the discussions, Colonel Popov, encouraged the Greek Communists to accept Churchill’s terms. ‘If we had not intervened’, Churchill told the British War Cabinet on his return to London, ‘there would have been a massacre’. There might also have been a Communist presence in the Aegean Sea.

***

On December 26, as part of the continuing offensive against Germany’s oil resources, United States bombers again attacked the German synthetic-oil factory at Monowitz. By accident, a cluster of bombs fell on the SS sick bay at Auschwitz—Birkenau, killing five SS men. The raid of December 26 was judged a success; photographs of the factory taken a few days later by a high-flying reconnaissance plane showed ‘a good concentration of hits’. But several important parts of the synthetic oil production processes, although much damaged, were still working after the raid of December 26, and the slave-labour camp at Monowitz, as well as the dozens of other factories in the Auschwitz region, continued to employ thousands of Jewish men and women from Auschwitz.

During December, 2,093 women died in Auschwitz, leaving 18,751 on the camp roll-call on December 27. Three days later, a further roll-call established that there were 2,036 women working in the Monowitz group of factories, and 1,088 at the Union explosives factory nearby. Of the male inmates at Auschwitz 35,000 were working at Monowitz, and another 31,000 in other factories throughout the region.

It was still not clear how long the Germans would continue to control these regions beyond the 1939 frontiers of Germany. On December 26, Soviet forces, after a three-day battle, succeeded in surrounding Budapest, cutting off the German garrison from its last remaining supply route from Austria. Inside the city, the persecution of Jews had continued, as had the attempts, by Raoul Wallenberg and others, to protect them. On December 27, two Hungarian Christians, Sister Sara Salkhazi and the teacher Vilma Bernovits, were executed by the Hungarian Arrow Cross for hiding Jews.

***

In Budapest, as fighting continued in every suburb, two Soviet officers went forward on December 29, under a white flag of truce, to offer the Germans terms for the surrender of the city. The first of the officers, Captain Miklos Shteinmetz, a Hungarian by birth, was killed as he approached the German lines. The second of the officers, Captain Ostapenko, was killed by a shot in the back as he returned to the Russian lines. The Germans declined to surrender, or to parley. Two days later, Hungary declared war on Germany. The last remnant of the European Axis was broken.

In the air above Germany, British and American bomber attacks continued. ‘Large numbers of Allied aircraft flew over,’ Able Seaman Walker noted on the last day of December, in his prisoner-of-war camp, Marlag, across the River Elbe from Hamburg, and he added: ‘I saw them return later, presumably after attacking Hanover and Hamburg. Four hit and down in flames. One American baled out, parachute failed to open. Fell just outside wire at noon.’

These bombing attacks were proving disastrous for the German war machine. On December 29 a top-secret German Air Force message reported that Allied fighter-bomber attacks throughout the Saar region had destroyed road and rail installations on a massive scale, eliminating telephone facilities, and making it impossible to re-route military supply trains. An Ultra decrypt three days later gave the Allies knowledge of this—for them highly successful—state of affairs.

On the last day of 1944, more than two years after their earlier attempt, British bombers again attacked the Gestapo Headquarters in Oslo. Although a substantial part of the building was destroyed, the damage to nearby buildings was considerable, and there were also civilian deaths; during the raid a tramcar full of people was hit. Only four of the passengers survived.

***

Surveying the war zones in Europe and Asia, it was clear that the year 1944 had ended disastrously for both Germany and Japan. In Europe, almost every square mile of territory conquered by Germany between 1939 and 1942 had been wrenched away. In the Pacific, the vast island empire conquered by Japan in 1942 was being slowly but inexorably eroded. Only Japan and Germany remained as effective war making powers on the once diverse Axis side; Roumania, Bulgaria and, on the last day of the year, Hungary, had cast their lot with the Allies. It was clear that neither Germany nor Japan was prepared to surrender. Both were determined to fight, not only on conquered soil, but on their own native land, and to do so to the bitter end, town by town and mile by mile. The Allies had no choice but to go on fighting the war on these terms, knowing that the cost in the lives of their soldiers, and of their airmen—already high—was likely to continue to climb. Yet the secret weapons of which Hitler had so boasted, and threatened, in the past, had proved, while capable of killing thousands of civilians, to be nevertheless quite indecisive in terms of the outcome of the war. By contrast, the still secret atomic weapon of the Western allies was giving those who knew about it a sense of impending triumph.

There was, however, one further German secret weapon in which, as 1944 came to an end, Hitler put his faith. When he had spoken of a ‘secret’ weapon in 1939, he had meant no more than the German Air Force, in itself a formidable instrument of war. Since then, he had been able to cause a certain short-lived havoc with several inventions, from the magnetic mine in 1939 to the flying and rocket bombs in 1944. Now he had a device of which the Allies had known since 1940, when Dutch submarines then using it had escaped to Britain, but to which the Allies had no answer. It was the Schnorchel submarine breathing tube—known to the Allies as the ‘Schnorkel’—which, in conjunction with a considerably increased electrical battery performance, a rapid pre-fabricated system of submarine construction, and torpedo tubes capable of firing many torpedoes at a time, could sink eight ships at once. Yet the new submarines could not easily be sunk while at sea, for, once they were ready to enter Atlantic waters, they would have been extremely difficult to find. Even when the submarines’ own naval Enigma signals would have given away their location, the aircraft of coastal command would not have been able to find them on the surface to sink them; the revolutionary breathing tube would see to that.

The moment of greatest Allied expectations on land thus coincided with a new and grave anxiety at sea, as the new prefabricated submarines, being assembled at Kiel, Hamburg and Danzig, began exercising in the Baltic. It was this very exercising, however, which proved their undoing, as their own top-secret Enigma messages revealed to the British just where the exercises were taking place, and Bomber Command, from its bases in East Anglia, struck into the Baltic. Thus good Intelligence and skilful bombing, as well as one or two lucky hits on the dock facilities at Kiel, enabled what might have been a real danger to be averted. Only in May was Hitler’s final secret weapon ready to go to sea. By then it was too late.