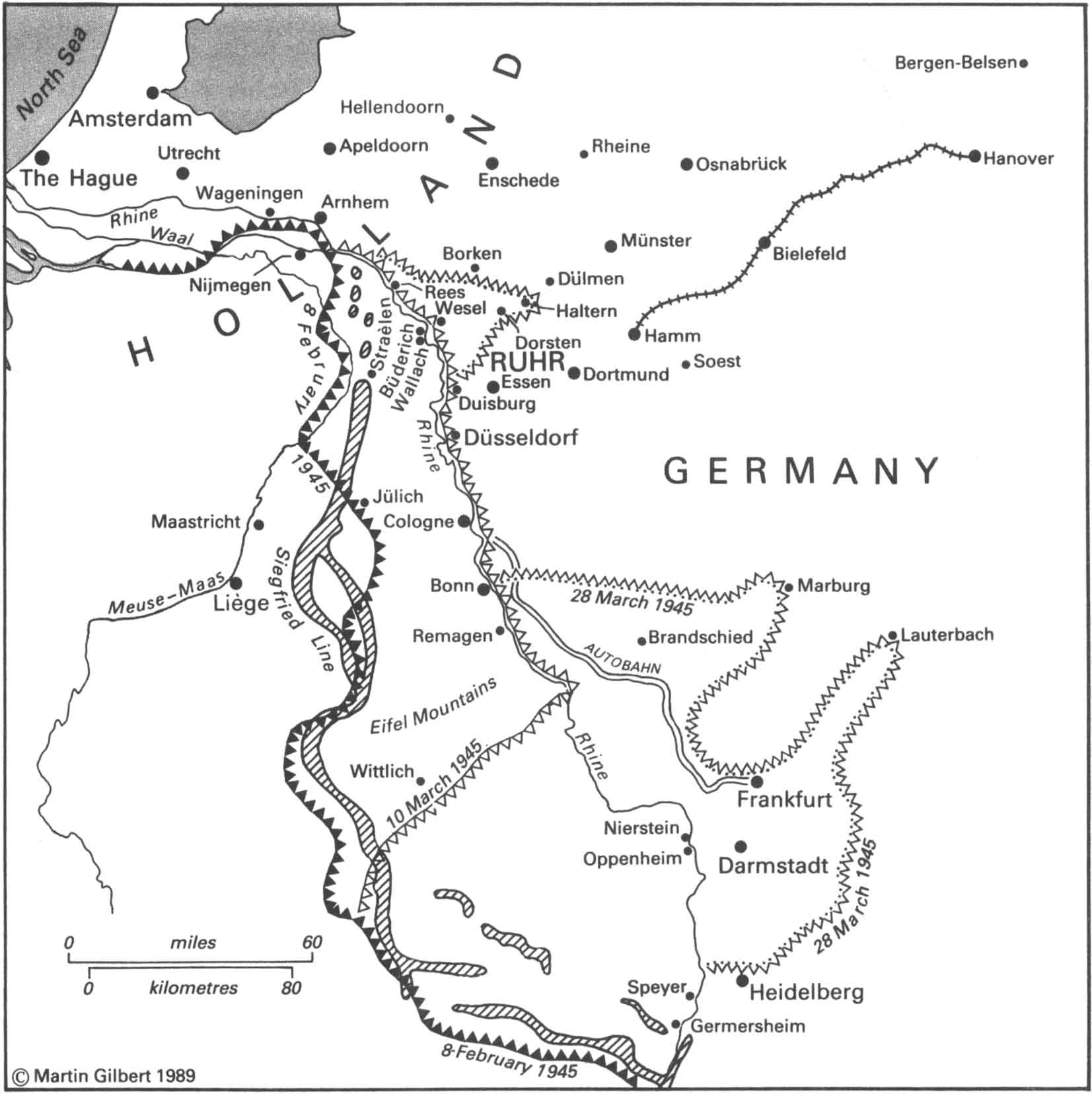

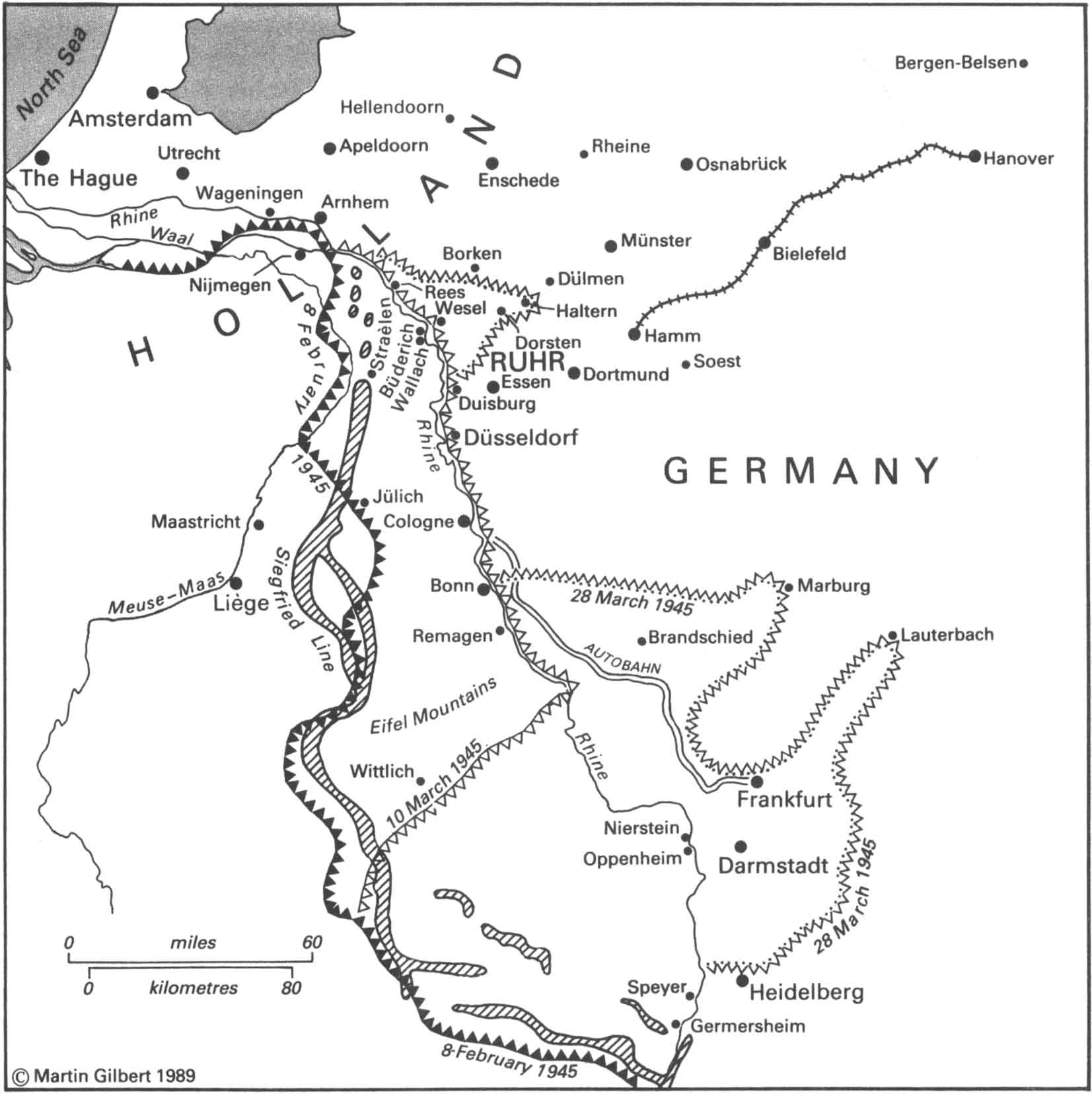

Crossing the Rhine, March 1945

On 1 February 1945, with the Red Army less than fifty miles away, Berlin was declared a Fortress City. Young and old were now set to work to build fortifications—trenches, earthworks, strongpoints and tank traps. On walls and buildings the old slogan: ‘Wheels must roll for victory’, was replaced by a new one: ‘Victory or Siberia’. At the Plötzensee Prison, anti-Nazis were still being put to death; among those who were hanged on February 2 were the Jesuit priest and member of the Kreisau Circle, Alfred Delp. Also hanged that day were Johannes Popitz, Hitler’s Reich Commissioner for Prussia and holder of the Nazi Party Golden Badge of Honour, who had tried to persuade his fellow conspirators to restore the monarchy after Hitler’s overthrow; and Carl Goerdeler, the former Lord Mayor of Leipzig, the leading non-military figure in the conspiracy against Hitler, and the man whom the generals had wanted to succeed Hitler as Chancellor.

At Sachsenhausen, on February 2, there was an act of heroism by one of Hitler’s prisoners, a British naval officer, Sub-Lieutenant John Godwin, who had been held prisoner with six other sailors since his capture on a clandestine mission to Norway in April 1943. Returning from the day’s forced labour, Godwin and the other six were taken, not to the barracks, but to an execution site. Seizing the pistol from the commander of the firing party, Godwin shot the commander dead, before he himself was shot down.

On February 3, the Berlin People’s Court met yet again to sentence further conspirators, each day’s trial being dominated by the unyielding severity, and personal abuse, of the President of the Court, Roland Freisler. That day, while the trial was taking place of Fabian von Schlabrendorff, of the widow of Wilhelm Solf, and of her daughter, the Countess Ballestrem—at whose home on 10 September 1943 many conspirators had been present—there was an American bombing raid on Berlin. The court was adjourned, and the prisoners were rushed, in manacles, to the cells. Freisler, clutching the files of the cases under consideration, each of which was about to be resolved with a sentence of death, was in the cellar of the courthouse when the building received a direct hit. He was killed by a falling beam.

Von Schlabrendorff, Frau Solf and the Countess Ballestrem, survived. Indeed, the Solf dossier having been destroyed with Freisler, their trial could not continue even in the reconstituted court, and they were later, through an oversight, released.

***

On February 4, near Brandschied, American forces breached the outer defences of the Siegfried Line. That day, in the Crimean resort town of Yalta, Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill met to discuss the political problems of post-war Europe, and in particular Poland. After considerable pressure from the two Western leaders, Stalin gave a series of assurances that free elections would be held, and that all Polish political parties could participate. These assurances were to prove valueless.

The Big Three also heard a plea on February 4 by the Deputy Chief of Staff of the Soviet forces, General Antonov, for British and American bombing help, ‘to prevent the enemy from transferring his troops to the East from the Western front, Norway and Italy’. What Antonov asked for was ‘air attacks against communications’. This Soviet request for Anglo-American air support was presented to the Big Three at their meeting on the afternoon of February 4, when Antonov told the meeting that the Germans were even then transferring to the Eastern Front eight divisions from the interior of Germany, eight from Italy, three from Norway and a further twelve from the Western Front, in addition to six already transferred. Antonov’s exaggerated assessment—only four divisions were transferred from Italy, for example—led Stalin to ask what Churchill and Roosevelt’s wishes were ‘in regard to the Red Army’, to which Churchill replied that they would like the Russian offensive to continue.

The urgency of the need for some Anglo-American air action to help that offensive continue was made clear by a sentence in the British Cabinet’s War Room Record that day, in which it was pointed out that ‘between the Oder bend north west of Glogau and the Carpathians all Russian attacks failed in the face of strengthened German resistance’. On the following day, in a memorandum for the Combined Chiefs of Staff, the British Chiefs of Staff agreed ‘to do what is possible to assist the advance of the Soviet Army’. That same day, at a meeting of the joint British, United States and Russian Chiefs of Staff, General Antonov went so far as to warn the Western generals that if the Allies ‘were unable to take full advantage of their air superiority they’—the Russians—‘did not have sufficient superiority on the ground to overcome enemy opposition’.

The British and American Chiefs of Staff at once agreed to deflect some of their bomber forces from the attack on Germany’s oil reserves and supplies, then the current priority, to an attack on the German Army’s lines of communication in the Berlin—Dresden—Leipzig region. They also agreed, at Antonov’s suggestion, that these three specific cities should be ‘allotted to the Allied air forces’, leaving the Russian bombers to attack targets further east.

Thus, at Yalta, in an attempt to help the Red Army halt the flow of German troops through Dresden and other cities to the Eastern Front, the fate of Dresden—which for ‘Bomber’ Harris remained one of the few major unbombed cities—was sealed. It was Harris who, in his capacity as head of Bomber Command, had for so long resisted the call to focus his strength against Germany’s oil resources, preferring to put his faith, which all Allied Intelligence including Ultra had shown to be misplaced, in the creation of firestorms and rubble.

Discussing the military balance of forces, Stalin pointed out to Roosevelt and Churchill, at their meeting on February 5, that the Red Army had put 180 divisions in the field, against 80 German divisions, ‘a preponderance of over two to one’, and went on to ask: ‘How did we stand as regards preponderance of troops in the West?’ Churchill, answering, explained that neither in France nor Italy did the Anglo-American forces have ‘any large preponderance’ in infantry, although they had ‘an overwhelming preponderance in the air, and also in tanks at those points at which we had decided to concentrate force’. On the Western Front, General Marshall told the Big Three, the Germans had seventy-nine divisions, albeit greatly under strength, as against seventy-eight Allied divisions.

That night, the Red Army again crossed the Oder, this time at Brieg, twenty-five miles below Breslau. Further north, two days later, Soviet troops crossed the river at Fürstenberg, sixty miles from Berlin, The Germans were dismayed. ‘The troops are pretty well fed up to the back teeth’ was von Rundstedt’s private comment that day. Yet the fanaticism of the German soldier continued to amaze those whose armies had come so far and won so many battles; in Poznan, and in Glogau, the German garrisons refused to surrender, while in Breslau, not yet besieged, more than 40,000 troops prepared to resist the Russian attack.

On the Western Front, on February 8, Canadian forces launched Operation Veritable, aimed at driving south from Nijmegen, to capture the area between the River Maas and the River Rhine, and thus force the Germans from the western bank of the Upper Rhine. On the following day, General de Lattre de Tassigny completed Operation Cheerful, against the Germans trapped in a pocket at Colmar. During the battle, which had lasted twenty days, 1,600 French and 540 American soldiers were killed; when the battle ended, and the Germans pulled back across the Upper Rhine, 22,000 German soldiers were taken prisoner.

That night, in Berlin, Hitler was shown an architectural model for the reconstruction of Linz once the war was over. To SS General Kaltenbrunner, who had reported on the sharp fall in public morale, Hitler remarked: ‘do you imagine I could talk like this about my plans for the future if I did not believe deep down that we really are going to win this war in the end!’

***

In Manila, on February 9, Japanese troops rounded up more than twenty girls, whom they proceeded to rape over the next three days. Some were raped more than thirty times. Only when the building in which the girls were being confined was hit by American shell fire did some of them manage to escape. One of them, Esther Gracia Moras, was later to give evidence of this atrocity at the Tokyo War Crimes trial.

***

At Yalta, Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin agreed on February 10 that Germany should pay reparation for the damage done by her occupation. At Stalin’s request, all Russians who had been captured fighting in the ranks of the German Army were to be repatriated—‘sent to Russia as quickly as possible’ were Stalin’s words. Many of these troops had opposed the Allies during the Normandy landings. It was also agreed that the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan two or three months after Germany had been defeated, and to receive in return both southern Sakhalin, annexed by Japan from Russia in 1905, and the Kurile Islands, acquired by Japan—in part from Russia and in part from China—in 1875.

On the day of these decisions, a renewed Soviet offensive was launched against the Germans in East Pomerania, where Himmler’s Vistula Army Group was still holding on at the lower reaches of the river, south of Danzig. In Budapest, a German force of 16,000 was still trying to break out of the city; encircled at Perbal, it was destroyed; only a few hundred soldiers were able to escape. Inside Buda, that part of the capital which lay on the western bank of the Danube, all German resistance was coming to an end, as 30,000 Germans surrendered, their ammunition, strength and willpower gone.

***

In the first two months of 1945, German rocket bomb attacks on Britain had continued, with 585 civilians being killed in January and a further 483 in February. Among those who died in Britain on February 13 was Leading Seaman Tommy Brown, who, two years earlier, had been awarded the George Medal for bravery at sea. When two of his sisters were trapped in a burning tenement building, he tried to rescue them, but was killed in the attempt.

***

On the night of February 13, as part of the Anglo-American plan, agreed at the Yalta Conference, to delay for as long as possible German troop reinforcements being transferred from Norway, Italy and Holland to the Eastern battle zone around Breslau, 245 British bombers struck at the city of Dresden, followed three and a half hours later by 529 more. Their purpose was to destroy the city’s railway marshalling yards. During the first of the two raids, a firestorm, created in a single hour’s bombardment, burnt through eleven square miles of the city.

The British raid on Dresden was followed the next morning by an American raid, also aimed at the marshalling yards, in which 450 bombers took part. Dresden, whose ancient city centre had hitherto been untouched by war, was now on fire; some of the fires were to burn for seven days and nights. Of the total of more than 1,200 bombers which had cast their bombs on the city, only eight were shot down. For the British bombers, this was the lowest ever ‘chop rate’ over Germany; it was also their deepest ever penetration into Germany. Most of Dresden’s anti-aircraft defences had been sent to the Western Front, to defend the Ruhr, and to protect Germany’s synthetic-oil plants.

On the morning of their February 14 raid on Dresden, American bombers also dropped 642 tons of bombs on Chemnitz and 752 tons on Magdeburg. That morning, Churchill, who was on his way back to Britain from the Crimea, received a telegram from the War Cabinet Office in London reporting on eleven aspects of the previous day’s military events. On the Western Front, he learned, six thousand German soldiers had been captured. In North Russia, a British convoy of twenty-eight ships had arrived without loss. In central Burma, a series of Japanese attacks had been beaten back. In central Europe, Budapest had been entered by Russian troops, and tens of thousands of German soldiers killed in the battle. In the air—and this was the tenth item in the list of eleven—Bomber Command had despatched a total of 1,252 aircraft over Germany, of which 805 had been sent to Dresden, 368 against the Böhlen synthetic-oil factory, 71 against Magdeburg and eight against the oil refinery at Misburg.

The eleventh and final item in this War Cabinet Office telegram concerned the continuing V2 rocket attacks on Britain. In the fifteen hours before daybreak on February 14, fourteen rockets had fallen in the London area, killing twelve civilians at Wood Green, twelve at Romford, twenty-eight at West Ham and three at Bexley. The total number of rocket bomb deaths in the week ending February 15 was 180, the highest since the rocket attacks had begun.

That same day, the first British report on the Dresden raid was prepared, based on an analysis of aerial photographs. Although it gave no casualty figures, the report noted the ‘great material damage’ to be seen in the photographs, adding that it was ‘apparent, from the many blocks of buildings seen gutted, that fires have already destroyed part of the city’. Interpretation of further photographs taken on February 15 was ‘rendered difficult’, the Chiefs of Staff Committee learned a week later, ‘by the haze from fires still burning more than thirty-six hours after the last attack’.

***

On the morning of February 15, less than thirty-six hours after the first British bombers had flown over Dresden, a second wave of two hundred American bombers attacked the still burning city, on the assumption that even more havoc could be caused if an attack were made while fire-fighting equipment and personnel were at work in the streets, and could themselves be hit.

The death toll at Dresden has never been calculated with precision. In all, 39,773 ‘officially identified dead’ were found in the city and registered, most of them burned to death. At least twenty thousand more bodies were buried beneath the ruins, or incinerated beyond recognition, even as bodies. The inscription on the mass grave in Dresden’s main cemetery asks: ‘How many died? Who knows the number?’ It hazards no answer.

For miles around, the glow of Dresden had been seen in the night sky, an incredible sight in the heart of Germany. In a labour camp at Schlieben, one of the Jewish slave labourers, Ben Helfgott, who in September 1939 had witnessed the burning of Sulejow in Poland, later recalled the red sky above Dresden: ‘Not only could we see it, the earth was shaking. We were out watching it. We were in heaven. It was like a boon for us. We didn’t have to work. The Germans were running for their lives. We knew that the day of our liberation must be drawing nearer. To all of us, it was absolute salvation. That was how we knew that the end was near’.

British and American prisoners-of-war were brought into Dresden to dig out the bodies. One of these prisoners, Kurt Vonnegut, later a distinguished American novelist, recalled: ‘Every day we walked into the city and dug into basements and shelters to get corpses out, as a sanitary measure. When we went into them, a typical shelter, an ordinary basement usually, looked like a streetcar full of people who’d simultaneously had heart failure. Just people sitting there in their chairs, all dead’.

Such unusual occurences had been seen in a number of Germany’s bombed cities since the Hamburg firestorm two and a half years earlier, when 42,000 had died.

***

In the Philippines, American forces, having driven a wedge between the Japanese forces, now pressed in upon Manila. On February 15, American carrier-based aircraft attacked the Japanese home islands for the first time, as the most powerful naval force that had ever put to sea—twenty aircraft-carriers escorted by ninety warships—steamed off Honshu Island.

On February 16, an American parachute regiment landed on Corregidor. That same day, as American carrier-based aircraft began the bombardment of Japanese installations on the island of Iwo Jima, an American expeditionary force set sail for Iwo Jima from Saipan.

In the battle for Manila, the Japanese soldiers, refusing to surrender, turned every street and every building into a savage battleground, reducing a once beautiful city to ruins and carnage. In an orgy of killing, nearly a hundred thousand Filipino civilians were murdered by the Japanese; in some cases, hospitals were set on fire after the patients had been strapped to their beds. The killing of Filipino civilians had reached a frenzy. ‘In various sectors’, a Japanese soldier noted in his diary on February 17, ‘we have killed several thousand (including young and old, men and women), and Chinese’.

On February 17, two thousand Japanese soldiers took up position inside Manila’s ancient walled city. With them were five thousand Filipino hostages. Over a loudspeaker, the American commander, General Oscar Griswold, urged the Japanese to surrender. They would not do so; six days and six nights later, with the ancient city in ruins, and almost every one of the Japanese and the Filipinos dead, yet another Allied victory had been secured.

***

At dawn on February 19, American marines landed on Iwo Jima, an eight square mile barren island, and an airbase judged essential for the bombing of Japan. After three days of violent fighting, in which hundreds of Americans were literally blown to pieces by the Japanese artillery, the American flag was raised above Mount Suribachi, the highest point on the small island. It was 10.20 in the morning. Of the dozen flag raisers, two—Lieutenant Colonel Chandler W. Johnson and Sergeant Ernest T. Thomas—were subsequently killed in action, Thomas on his twenty-first birthday.

A Marine photographer, Sergeant Louis R. Lowery, photographed the scene, but his photograph, sent back by ordinary army post to Marine headquarters in the United States, took a month to arrive. Meanwhile, a second flag raising, which had taken place an hour after the first, was photographed by an Associated Press photographer, Joe Rosenthal. His photograph, sent by seaplane to Guam, and on from there by radio-photo to the United States, was immediately acclaimed as extraordinary, so much so that President Roosevelt ordered the six flag raisers seen in it to come home to share their glory with all their fellow-Americans.

By the time Roosevelt’s order reached Iwo Jima, three of the six—Captain Harlon Block, Sergeant Michael Strank and Private Franklin R. Sousley—were already dead. Joe Rosenthal won a Pulitzer prize for his photograph, and, while the struggle against Japan still raged, the United States Post Office Department issued a three-cent Iwo Jima Flag Raising Stamp, the first United States stamp of the war to show a Second World War scene. The photograph of this second flag raising was to become the most frequently-reproduced photograph of the Pacific war.

The flag had been raised, but the battle for Iwo Jima went on, across strongly contested ridges and ravines such as ‘Bloody Gorge’, the ‘Meat Grinder’, and the ‘Mincer’. Victory on Iwo Jima did not come until the end of March, after the death of 6,821 American marines, and of 20,000 of the Japanese defenders. Only 1,083 Japanese had allowed themselves to be captured.

Nearly nine hundred American sailors were also killed during the battle for Iwo Jima, 218 of them when the escort carrier Bismarck Sea was sunk by a Japanese suicide aircraft.

Following the capture of Iwo Jima, American bombers, based on the island, began the regular and relentless bombing of the Japanese home islands. On Luzon, with Manila at last under American control, the fighting continued, as did the attempts to rescue American prisoners-of-war. In a raid by American troops and Filipino guerrillas on Los Banos prison camp, south of Manila, the whole Japanese garrison was killed, and 2,100 prisoners-of-war rescued, for the loss of only two Americans.

***

In Germany, the sound of artillery fire could now be heard at Peenemünde, home of the V2 rocket. On February 17, the rocket scientists left the centre by train, their equipment sent westward by barge. By the end of the month, both had reached Oberammergau, in Bavaria, rumoured to be the region to which Hitler would retreat for the final fight. In Silesia, Breslau was now besieged.

On February 19, at this moment of crisis for the German Army in the East, Heinrich Himmler, acting behind Hitler’s back, met a Swedish Red Cross official, Count Folke Bernadotte, to ask the Swede if it might be possible to open negotiations with the Western Allies. Bernadotte, a skilful negotiator, suggested that as a first step the concentration camps might be transferred to the International Committee of the Red Cross. Himmler was willing to allow the inmates to receive Red Cross food parcels—but only the ‘Nordic’ inmates, not Slavs or Jews. The two men agreed to meet again.

On February 21, Hitler’s military advisers urged him to pull back all German troops from Pomerania. He refused to do so, insisting that the railway line from Stettin to Danzig be held at all cost. On the following day, the German garrison in Poznan surrendered, their commander having committed suicide. There was now no way that Pomerania could be retained.

One last Allied bombing effort was about to be made to destroy German communications throughout the Reich: Operation Clarion. Two early but accidental victims, on February 22, were the two Swiss border towns of Stein am Rhein and Rafz, in which seventeen Swiss civilians were killed.

In all, nine thousand aircraft took part in Operation Clarion, hitting at railway yards, canal locks, bridges and vehicles without pause for twenty-four hours. In a raid on Pforzheim on the night of February 23, Captain E. Swales held his crippled bomber in the air for long enough to allow his crew to parachute to safety; he died when the bomber crashed, and was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross. Captain Swales was one of 2,227 members of the South African Air Force who were killed in action during the Second World War.

On February 24, as the Operation Clarion bombing raids were in progress, Hitler met his Gauleiters in Berlin. ‘You may see my hand tremble sometimes today,’ he told them, ‘and perhaps even my head now and then; but my heart—never!’ On the Western Front, no Allied soldiers had yet crossed the Rhine. On the Eastern Front, the Oder, although bridged in several places, was still serving as an effective barrier to any Russian attempt to move closer to Berlin.

***

On February 26, the Americans on Corregidor Island prepared for victory. For two weeks, they had fought to defeat the Japanese on the island fortress from which they had been driven three years earlier. In the struggle to retake the tiny island more than three thousand Japanese soldiers, all but a handful of the garrison, had been killed. Then, in a final act of mass defiance and suicide, the Japanese hiding in the tunnels under Monkey Point blew up the largest ammunition dump on the island; fifty-two American soldiers were killed in the explosion. The two hundred Japanese in the tunnel were also dead and 196 Americans injured. ‘As soon as I got all the casualties off,’ wrote Captain Bill McLain, a battalion surgeon, ‘I sat down on a rock and burst out crying. I couldn’t stop myself and didn’t even want to. I had seen more than a man could stand, and still stay normal.’

By nightfall on February 27, when organized resistance on Corregidor ended, some six thousand Japanese were dead. Earlier that day, while fighting was still going on in Manila’s walled city, General MacArthur had reached the Malacanan Palace, where he told the Filipinos present that their country was ‘again at liberty to pursue its destiny to an honoured position in the family of free nations’. As for Manila itself, MacArthur added: ‘Your capital city, cruelly punished though it be, has regained its rightful place—citadel of democracy in the East.’ He then broke down and wept. Later he was to write: ‘To others it might have seemed my moment of victory and monumental personal acclaim, but to me it seemed only the culmination of a panorama of physical and spiritual disaster. It had killed something inside me to see my men die.’

On February 28, American forces landed at Puerto Princesa, on Palawan Island, where they immediately began to search for the prisoners-of-war who had been held there for the past three years. What they found were only a few identity discs and personal belongings. Two weeks later they were to find seventy-nine skeletons, twenty-six of them in a mass grave. Bullets had pierced the skulls, which had also been crushed with blunt instruments.

The landing at Puerto Princesa was the first of thirty-eight assaults against the 450,000 Japanese soldiers in the islands of the southern Philippines. Six principal islands were invaded within two weeks, culminating on March 10 with Mindanao. Other landings continued until July, the reconquest of these islands costing more than thirteen thousand American lives.

***

On February 28, British Intelligence informed the Soviet Military Mission in London of the German Army’s order of battle on the Eastern Front. This information had come from Ultra. That same day, after German documents captured at Strasbourg had confirmed that the Auer Factory at Oranienburg, north of Berlin, was involved in the manufacture of uranian metals for atomic energy, orders were given to bomb the factory as a matter of priority.

On the Western Front, American forces reached the Rhine opposite Düsseldorf on March 2, but found that all the bridges had been destroyed. That day, as German forces still held the Russians at bay in Breslau, American bombers again struck at Dresden, their target once more the marshalling yards through which the Breslau front was being fortified and reinforced. One of the casualties that day was a hospital ship on the Elbe, crowded with injured from the earlier raids.

On March 3, Finland declared war on Germany. Turkey had already done so ten days earlier. By these two declarations, Finland and Turkey both earned their place at the table of the victor powers. In Germany itself, Churchill, visiting the Western Front, was in Jülich that day, the first time a British Prime Minister had been on German soil since Neville Chamberlain had gone to Munich in September 1938, to concede the Sudetenland regions of Czechoslovakia to Germany.

In Berlin, which had celebrated with such enthusiasm the bloodless success of those early annexations, March 3 saw yet another execution of a German who had tried to overthrow the Nazi regime. The victim that day was Ernst von Harnack, a former Prussian civil servant and Social Democrat who, when Hitler came to power in 1933, had denounced the new Government as one ‘without goodness or grace’.

On March 3, the Germans launched the first VI flying bombs against London since the previous September. Twenty-one missiles were fired from aircraft. Seven of them reached the London area. Fears for the state of morale in London if the V2 raids were intensified led, that same day, to a British bombing raid on the rocket launching site near The Hague. By accident, many of the bombs fell on residential areas, and 520 Dutch civilians were killed.

On the following day, March 4, American bombs, falling accidentally on Zurich, killed five Swiss civilians. The bombers responsible were on their way from bases in Britain to bomb the German industrial city of Pforzheim.

***

On March 4, American bombers hit the Musashino aircraft factory in Tokyo. This was their last precision bombing raid over Japan; henceforth, the Americans were to resort only to ‘carpet’ bombing, of the sort that had devastated Dresden in February. In Burma, British and Indian troops were advancing both along the Arakan coast—driving the Japanese from Tamandu on March 4—and towards Mandalay.

***

On March 5, the German Army began to enrol all boys born in 1929, even before they reached their sixteenth birthdays. That day, in northern Hungary, German forces launched Operation Spring Awakening, to try to push the Red Army back from the approaches to Vienna. Despite the scepticism of his generals, Hitler was convinced that Budapest could be recaptured, followed by the Hungarian oilfields, which, only a few months earlier, after the loss of the Roumanian oilfields at Ploesti, had provided more than three-quarters of the oil available to Germany.

Ironically, lack of fuel was one of the reasons why the German offensive in search of oil failed. Spring Awakening also coincided with the spring thaw, exceptionally muddy conditions making it particularly hard to advance.

In Holland, a senior SS officer, General Rauter, was accidentally killed on March 6, during an attempt by some young members of the Dutch Resistance to hijack a truck near Apeldoorn. The fact that Rauter’s death had been an accident did not avert reprisals; in the week that followed, 263 Dutchmen were shot. Many of them were so-called ‘Death Candidates’, Resistance fighters and others who had been held for some time in prison in Amsterdam and Utrecht. Before the executions started, a member of the German police firing squad, Helmuth Seijffards, refused to take part. He was arrested, and later shot. During the execution itself, Jan Thijssen, leader of one of the main Dutch Resistance groups, tried to escape; he was caught, and shot with the others.

News of executions of another sort reached London on March 6; the killing in Poland, by the Russians, of Poles loyal to their London Government-in-exile. According to these reports, there had been ‘mass arrests’ in the Cracow area of Poles loyal to the London Government or active in the Home Army underground. Two train loads ‘of two thousand persons each’ had been deported from Poland to labour camps in the Soviet Union. As many as six thousand former Home Army officers were in a camp near Lublin directed by Soviet officials. ‘Prisoners are badly treated,’ the report asserted, ‘and many are removed every few days to an unknown destination.’ Home Army men arrested in Bialystok ‘are starved, beaten and tortured, and accused of spying for Great Britain and for the Polish Government in London as well as of collaboration with the Germans. There are many deaths.’ Refugees were now beginning to trickle home from the liberated camps and regions. A few weeks earlier, twenty Jews returned to their home in the small village of Sokoly, near Bialystok, now liberated from the Nazi yoke. But the local Poles did not want them back, and seven of the Jews were killed, among them a four-year-old orphan girl.

***

On the morning of March 7, American troops reached the River Rhine at the town of Remagen, whose inhabitants quickly hung out white flags to avert a conflict. Spanning the river at Remagen was a railway bridge—intact. It was the Ludendorff bridge, one of the great railway bridges of Germany built during the First World War. As the Americans approached it, German engineers on the far bank set off the first of their explosive charges, but the bridge remained intact. The main charge had failed to go off.

Crossing the Rhine, March 1945

Disconnecting the charge, the American soldiers set off across the bridge. ‘We ran down the middle of the bridge,’ Sergeant Alexander A. Drabik, from Ohio, later recalled, ‘shouting as we went. I didn’t stop because I knew that if I kept moving they couldn’t hit me. My men were in squad column, and not one of them was hit. We took cover in some bomb craters. Then we just sat and waited for the others to come.’ By early evening, a hundred American soldiers had crossed the Rhine.

The Western Allies now stood on the eastern bank of the Rhine. No enemy or invader had crossed the Rhine into Germany since Napoleon had done so in 1805.

That night, as the Americans consolidated their bridgehead on the eastern bank of the Rhine, Hitler dismissed Field Marshal von Rundstedt from his post of Commander-in-Chief of the German forces in the West. ‘He is finished,’ Hitler declared. ‘I don’t want to hear any more about him.’

In Italy, a senior German Army officer, SS General Karl Wolff, had decided to negotiate the surrender of all German forces in Italy. On February 25, he had sent an emissary to Switzerland, to open talks with the American Secret Service Chief in Berne, Allan Dulles. As proof of his seriousness, Wolff agreed on March 8 to release two men imprisoned by the Germans in Italy, the Italian Resistance leader Ferruccio Parri, and an American agent, Major Antonio Usmiani. Both were taken from their prison cells to the Swiss border on March 8, together with General Wolff himself and three other German officers. They went to Zurich, scene of the recent accidental bombing by the Americans, and began negotiations. ‘I control the SS forces in Italy,’ Wolff told Dulles, ‘and I am willing to place myself and my entire organization at the disposal of the Allies, to terminate hostilities.’ He would have, however, as he explained, to persuade the German commanders in the field to agree. Promising to seek their approval, Wolff returned to Italy.

On March 8, when a V2 rocket bomb fell on Smithfield market in London, 110 people were killed. In Germany, the Allies were completing their conquest of the west bank of the Rhine. On March 9, American troops entered Bonn. Far to the West, five hundred miles behind the battle front, German troops on the Channel Islands made a swoop, from their own beleaguered garrison, on the French port of Granville. Ultra had given warning of the Granville raid, but had been given insufficient attention, so improbable did such a raid seem at this stage of the war. At a cost of four men killed, the Germans landed on French soil, blew up several port installations and released sixty-seven German prisoners-of-war being held at Granville by the Americans. During the raid, the commander of a British merchant ship was also killed, and a British civilian, John Alexander, taken prisoner; Alexander was the Principal Welfare Officer of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, UNRRA, which, from its headquarters at Granville, was sending its personnel to all the liberated areas of Europe, to co-ordinate a massive relief programme, as well as arranging to house displaced persons in Granville itself. Alexander was imprisoned in the Channel Islands until the end of the war, together with five American soldiers captured that same day. Fifteen American and eight British servicemen had been killed, as well as six French civilians. One of those killed was Lieutenant Frederick Lightoller, the Port Liaison Officer, whose brother Pilot Officer Herbert Brian Lightoller had been one of the very first Englishmen killed in the war, during a raid on Wilhelmshaven in September 1939.

The Americans were shocked by the Granville raid; during it, according to the official American report, the enemy ‘had complete control of the Granville area, and were his objective that of conquest, he was the conqueror’.

***

In the Pacific, the Americans’ own road to conquest was marked, on March 9, with the first day of a new bombing offensive against Japan itself, when, in a raid lasting less than three hours, 334 American bombers, flying from Tinian Island, dropped two thousand tons of incendiary bombs on Tokyo. In a firestorm of even greater proportions than that of Dresden three weeks earlier, almost sixteen square miles of Tokyo were burned out, and 83,793 Japanese civilians killed. That was the official minimum death toll; later, 130,000 deaths were ‘confirmed’ by the Japanese authorities.

The March 9 raid on Tokyo was the most destructive single bombing raid yet known. But it was only the first of the firestorm raids. In the next three months, the cities of Nagoya, Osaka, Kobe, Yokohama and Kawasaki were likewise attacked and pulverized, and more than a quarter of a million Japanese civilians killed, for the loss of only 243 American airmen—the same number of airmen as had been lost a year and a half earlier during a single British bombing raid on Berlin.

***

On March 11, Hitler drove from Berlin to the western bank of the River Oder, to see for himself the defensive preparations being made between the Oder and the capital. He was never to leave Berlin again. On the following day, as the Americans completed the occupation of the west bank of the Rhine, having taken 343,000 German prisoners-of-war, the Red Army entered Küstrin, eliminating one of the last bridgeheads held by the Germans on the eastern bank of the Oder, and coming to within fifty miles of Berlin.

Before attempting to cross the Rhine in force, the British and Americans sought to pulverize the German lines of communication leading up to the river. On March 14 the Bielefeld railway viaduct linking Hamm and Hanover was destroyed. A new type of bomb, exceeding in size any hitherto dropped, was used in the attack. On the previous three days, massive attacks had already been made by British and American bombers on railway marshalling yards and bridges at Essen, Dortmund, Münster, Soest, Osnabrück and Hanover, as well as on the Ruhr towns of Rheine, Borken, Dorsten and Dülmen.

Since the American seizure of the bridge over the Rhine at Remagen, German troops had fought in vain to destroy the narrow bridgehead. There had also been a series of attempts to destroy the bridge, including the firing of eleven V2 rockets from their base at Hellendoorn, in Holland. One rocket landed only three hundred yards from the bridge; another fell twenty-five miles away, near Cologne. On March 15, during one of the daily German Air Force raids on the bridge, sixteen out of the twenty-one German bombers were shot down. Many of those shot down were jets.

Also on March 15, American bombers, at the urgent request of Major-General Leslie R Groves, the head of the American atomic bomb ‘Manhattan’ Project, dropped nearly 1,300 tons of high explosive and incendiary bombs on the German thorium ore processing plant at Oranienburg. All the above-ground parts of the plant were completely destroyed, and German atomic bomb research brought to a halt.

On March 16, American units further extended the Remagen bridgehead, cutting the Cologne—Frankfurt autobahn. Then, on March 17, worn out by the pounding of American artillery units nearby, the bridge collapsed; twenty-five American engineers were killed. By then, however, two temporary bridges had been thrown across the river, and several thousand troops were on the far side. Not knowing that the bridge had collapsed, on the night of March 17, six German frogmen entered the Rhine upstream and, using oil drums, floated explosive charges towards the bridge. All six were seen, and captured.

Hitler was still confident that he could avert defeat. On March 17 a new submarine set sail for the eastern seaboard of the United States. It was one of many that were now able to remain under water almost indefinitely, using the Schnorchel breathing tube. Jet aircraft were now a regular component of German Air Force assaults. The line of the Oder, and the line of the Rhine, although both had been crossed, were still serving as effective barriers. Even Churchill was worried that week about the extent to which Hitler might still be able to prolong the war. ‘I should like the Intelligence Committee’, he informed the Chiefs of Staff on March 17, ‘to consider the possibility that Hitler, after losing Berlin and Northern Germany, will retire to the mountainous and wooded parts of Southern Germany and endeavour to prolong the fight there.’ The ‘strange resistance’ which the Germans had made at Budapest, and were now making at Lake Balaton, and the retention for ‘so long’ of Kesselring’s Army in Italy seemed, Churchill wrote, ‘in harmony with such an intention’. He added: ‘But of course he is so foolishly obstinate about everything that there may be no meaning behind these moves. Nevertheless the possibilities should be examined.’

***

In the Pacific, as American carrier-borne aircraft struck at the Japanese fleet in the Kure—Kobe area on March 18, a new Japanese suicide weapon was launched, a flying bomb with a pilot who guided it on to its target, and died in doing so. During the first of these suicide bomb attacks, the aircraft carrier Enterprise was accidentally damaged by shrapnel from another American warship, while 101 men were killed on board the new aircraft carrier Wasp. Japanese losses, however, were formidable; of 193 aircraft committed to the battle, 161 were shot down. Two days later, British and Indian forces in Burma entered Mandalay.

***

In Germany, the third week of March saw the execution in Berlin of yet another senior Army officer, General Friedrich Fromm. He was shot by a firing squad on March 19. At the time of the July Plot, he had shown his loyalty to Hitler by arresting Count von Stauffenberg. But he had earlier intimated that he would join the conspiracy once it had shown that it could succeed.

That day, in Belsen, a roll-call showed that there were 60,000 inmates in the camp. Deprived of adequate food or medical help, overrun by disease, tormented by lice and dysentery—those who were dead mixed with the living, and even the living attacked by rats—several hundred inmates, most but not all of them Jews, were dying every day, their corpses left to rot where they lay.

In liberated Poland, commissions of enquiry were taking evidence of the atrocities and mass murders in every town and in hundreds of camps. On March 19, Chaim Hirszman, one of only two survivors of Belzec death camp, gave testimony in Lublin. He had so much to say that he was asked to come back on the following day. But on his way home he was attacked by Polish anti-Semites and murdered, because he was a Jew.

Inside Germany, on the day after Chaim Hirszman’s murder, a British Special Operations agent, Francis Suttill, was hanged in Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Before his capture in France two years earlier, he had been in charge of the ‘Prosper’ escape and evasion route.

***

In a low flying precision raid on March 21, eighteen British and twenty-eight American planes carried out a raid on the former Shell Petroleum Company headquarters in Copenhagen, on three floors of which the Gestapo kept the records of what it had found out about the Danish resistance. On the top floor of the building, the Gestapo had imprisoned thirty-two Resistance fighters. In the basement, Danish citizens were being held and tortured. The attackers had therefore to hit only the three middle floors of the building. They did so. Nearly a hundred Germans and their collaborators were killed, but only six of the Danish prisoners on the top floor. The rest of the prisoners were smuggled out of Copenhagen and spirited away by ship to Sweden.

Nine aircraft were lost on the raid, and ten airmen killed. In the target area, one of the attacking aircraft hit a power line and crashed on to a school, where it exploded, setting fire to the school building. Other aircraft, thinking that the blazing building was their intended target, dropped their bombs on it. In all 112 Danish civilians were killed as a result of this mistake, including eleven nuns and eighty-six children.

Also on March 21, an Allied air attack was launched against all the main German jet airfields, many of which were made unusable. That same day, after having urged Hitler to conclude an immediate armistice in the West, General Guderian was dismissed. In 1940 and 1941, it was Guderian’s Blitzkrieg techniques that had secured Hitler the sequence of victories whereby Nazism had crushed most of Europe.

Hitler would not listen even to Guderian. On March 22, American forces secured two further bridgeheads over the Rhine, seventy miles south of Remagen, the first at Nierstein, the second at Oppenheim, only twenty miles from Frankfurt. ‘Don’t tell anyone,’ General Patton telephoned General Bradley on the morning of March 23, ‘but I’m across. I sneaked a division over last night. But there are so few Krauts around there, they don’t know it yet.’

Against the two new bridgeheads, the Germans did in fact send almost all their available jet aircraft, fifty of them on the night of March 23. But within twenty-four hours, shortage of fuel, and lack of undamaged airfields to land on, cut even this number by half. During March 23, in Hungary, the Red Army broke down the German defences at Szekesfehervar, ending any chance of a German reconquest of the Hungarian oilfields. That same night, on the Rhine, Canadian and British forces launched Operation Plunder, crossing the Rhine at Rees and Wesel, the crossing points being illuminated, and the German defenders blinded, by specially designed tank-borne searchlights, capable of thirteen million candlepower, and known, in tribute to the Army’s commander, as ‘Monty’s Moonlight’.

Montgomery’s two crossings were a success; they were followed, within forty-eight hours, by six more in the north, and seven more in the American zone of operations to the south. As the Germans pulled back from the river, the decrypters in Britain who continued to read the Germans’ own secret cypher messages learned exactly where the next German points of resistance were to be set up, as well as Hitler’s plan to drive back the bridgeheads north of the Ruhr by a counter-attack at Haltern and Dülmen. Knowing this, the Allies were able to forestall the intended counter-attack before it began.

On March 24, during the battle for Wesel, on the eastern bank of the Rhine, a Canadian medical orderly, Corporal F. G. Topham, saw two fellow orderlies killed while trying to get to a wounded man who had been hit in open ground. Topham managed to reach the man and then, although himself wounded in the face and in considerable pain, carried him back through heavy fire to safety. On being sent to the rear for treatment, Topham begged to be allowed to return to the front, where he once more went forward over open ground under fire, to help three men who had been badly wounded in an armoured carrier. For his ‘gallantry of the highest order’, Topham was awarded the Victoria Cross.

The Allied forces now thrust forward to encircle the Ruhr. As they did so, all possibility of Hitler’s jets being effective was brought to an end on March 25, as American forces overran the principal jet airfields in the regions of Darmstadt and Frankfurt. That day, Churchill, while visiting the Twenty-first Army Group, flew from a British airstrip at Straelen for more than an hour along the Rhine and east of the Meuse, for about 140 miles, at a mere 500 feet, unescorted, in a tiny Messenger aircraft. Churchill’s pilot, Flight-Lieutenant Trevor Martin, later recalled ‘seeing the flashes from our own artillery to the west of us’ as, in the cramped plane, with no radio, Churchill looked down on the German defensive positions east of the Meuse and the areas of British and American attacks east of the Rhine. ‘I was worried’, Martin recalled, ‘that the Americans in particular would not know that it was one of our aeroplanes.’

Returning safely to Straelen, Churchill was driven to Büderich, on the western bank of the Rhine, where he crossed the river in an American landing craft, setting foot briefly on the eastern side. Then, after crossing back, he clambered over the twisted girders and broken masonry of the road bridge at Büderich, while German shells fell into the river a hundred yards away. On the following day, Churchill crossed the Rhine again, spending more than an hour on the eastern side. It was a moment of deep satisfaction after five and a half years of struggle and setbacks, dangers and unceasing war. ‘The Rhine and all its fortress lines lie behind the 21st Group of Armies,’ he wrote in Montgomery’s autograph book on March 26, and he added: ‘A beaten army not long ago Master of Europe retreats before its pursuers. The goal is not long to be denied to those who have come so far and fought so well under proud and faithful leadership. Forward all on wings of flame to final Victory.’

On March 27, Argentina declared war on Germany and Japan, becoming the fifty-third nation to be at war. That same day, the Germans fired the last V2 rockets of the war, from their one remaining launching site near The Hague. One of the rockets, falling on London at 7 o’clock that morning, killed 134 people in a block of flats at Vallance Road, Stepney. Another, falling in Antwerp, killed twenty-seven people. In the afternoon, at Orpington in Kent, an Englishwoman was killed by a third rocket; she was the last civilian casualty in Britain. Two days later, the V2 crew retreated eastward, taking with them sixty unfired rockets. In England, 2,855 people had been killed, and in Belgium 4,483, by this particular ‘secret weapon’ since the previous September. On this, as on his other types of new weapon and scientific advance, Hitler had set great hopes. But in that same period, his mastery of Europe had been destroyed.