From the Rhine to the Elbe, April 1945

On 12 April 1945 President Roosevelt died at his home in Warm Springs, Georgia. Battle-hardened American soldiers wept when they heard the news. The Nazi leaders rejoiced: ‘This’, said Goebbels, ‘is the turning point.’ His view was shared by the Hitler Youth leader, Alfons Heck, who, at Wittlich, was already far behind the American lines, and who learned of Roosevelt’s death on an American soldier’s radio. ‘I shared Josef Goebbels’s short-lived illusion’, he later wrote, ‘that his demise might persuade his successor, Harry Truman, to settle for an armistice or even to join us against the Soviets.’

On Okinawa, the Japanese hailed Roosevelt’s death as a sign that their suicide ventures were effective. ‘Sudden death of President Roosevelt’, a Japanese leaflet announced gloatingly, and it went on to ask: ‘“Suicide” holding himself responsible for the defeat at Okinawa? “Assassination” laying the blame on him for the defeat?’

No such defeat was, however, in prospect, despite the ferocity of the battle on land and the continuing kamikaze attacks at sea. By coincidence, April 12 marked the day on which news about the very existence of the kamikaze, hitherto kept a strict military secret, was released to the American public.

That night, on Okinawa, Staff Sergeant Beaufort T. Anderson, in an attempt to stave off a Japanese counter attack on Kakazu Ridge, single-handedly advanced throwing his grenades and then, when he had no more grenades, took mortar shells and—having no mortar with which to fire them—banged each shell against a rock in order to release its pin, and then threw fourteen shells by hand against the advancing Japanese. Anderson survived. For his success in holding off that particular attack, he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honour.

Also awarded the Congressional Medal of Honour during the fighting for the Kakazu line was a medical orderly, Desmond T. Doss, who, as a Seventh Day Adventist, refused to carry a weapon. Under heavy fire, the only unwounded man on a high point on the ridge, Doss carried fifty wounded men one by one to the edge of a thirty-five foot drop, and then lowered them by rope to safety.

In Germany, on the day of Roosevelt’s death, at Stadtilm near Erfurt the Americans captured one of Germany’s two heavy-water piles. As a result, no German atomic bomb could be developed in the months ahead. On the following day, April 13, from his underground bunker in Berlin, Hitler issued a proclamation to the German troops on the Eastern Front. Deliverance was at hand. Berlin would remain German. Vienna—which the Russians had finally captured that very day—would be German again. ‘A mighty artillery is waiting to greet the enemy,’ Hitler promised, and he added, mendaciously: ‘Our infantry losses have been made good by innumerable new units.’

Even at this desperate eleventh hour for Germany’s armed forces, many units were still employed guarding, moving and killing Jews. ‘One night we stopped near the town of Gardelegen,’ Menachem Weinryb, a survivor of the death march from Auschwitz later recalled, of the events of April 13. ‘We lay down in a field and several Germans went to consult about what they should do. They returned with a lot of young people from the Hitler Youth and with members of the police force from the town. They chased us all into a large barn. Since we were five to six thousand people, the wall of the barn collapsed from the pressure of the mass of people, and many of us fled. The Germans poured out petrol and set the barn on fire. Several thousand people were burned alive’. Those who had managed to escape, Weinryb added, lay down in the nearby wood ‘and heard the heart-rending screams of the victims’.

Trapped in the barn, the Jews had tried to escape by burrowing under the foundation walls. But as their heads appeared on the outside, they were shot by the Germans surrounding the barn.

‘More than an end to war,’ Roosevelt had intended to tell the annual Jefferson Day dinner in Washington on April 13, ‘we want an end to the beginnings of all wars—yes, an end to this brutal, inhuman and thoroughly impractical method of settling the differences between governments.’ Not only differences between governments, however, but fierce racial hatreds, had been unleashed during the two thousand days of war which had already passed between Hitler’s invasion of Poland and Roosevelt’s death. This became all too clear in the third week of April, as camp after camp was overrun, including Gardelegen, where the Americans discovered the charred bodies of those burned in the barn, and Belsen, whose sadistic commandant, Josef Kramer, took the British soldiers who reached his camp on a ‘tour of inspection’, untroubled by the revolting nature of the scene with which he was confronting them.

It was on April 15 that the first British tanks entered Belsen. By chance, three of the British soldiers in the tanks were Jews. But the survivors could not grasp what had happened: ‘We, the cowed and emaciated inmates of the camp, did not believe we were free,’ one of the Jews there, Josef Rosensaft, later recalled. ‘It seemed to us a dream which would soon turn again into cruel reality.’

The ‘cruel reality’ came swiftly at Belsen, as those first British tanks moved on, in pursuit of the German forces. For the next forty-eight hours the camp remained only nominally under British control, with 1,500 Hungarian soldiers, who had been stationed in the camp as guards, remaining in command. During that brief interval, seventy-two Jews and eleven non-Jews were shot by the Hungarians, for such ‘offences’ as taking potato peel from the kitchen.

There were 30,000 inmates in Belsen at this moment of liberation postponed; 1,500 Jewish survivors from Auschwitz; a thousand Germans sent there for anti-Nazi activities; several hundred Gypsies; 160 Luxemburg civilians who had been active against the German occupation; 120 Dutch anti-fascists; as well as Yugoslavs, Frenchmen, Belgians, Czechs, Greeks, and, most numerous of all, Russians and Poles—a veritable kaleidoscope of Hitler’s victims.

When, after forty-eight hours, British troops did enter Belsen in force, the evidence of mass murder on a vast scale became immediately apparent to them. Of ten thousand unburied bodies, most were victims of starvation. Even after liberation, three hundred inmates died each day during the ensuing week from typhus and starvation. Despite the arrival of considerable quantities of British medical aid, personnel and food, the death rate was still sixty a day after more than two weeks.

‘People were falling dead all around,’ a British officer, Patrick Gordon-Walker, wrote of the scene as he entered the camp, ‘—people who were walking skeletons’, and he went on to relate a story told to him by the British soldier who had witnessed it. ‘One woman came up to a soldier who was guarding the milk store and doling the milk out to children, and begged for milk for her baby. The man took the baby and saw that it had been dead for days, black in the face and shrivelled up. The woman went on begging for milk. So he poured some on the dead lips. The mother then started to croon with joy and carried the baby off in triumph. She stumbled and fell dead in a few yards.’

About 35,000 corpses were counted by the British at Belsen, five thousand more than the number of living inmates. Among those living inmates were many who were too weak even to stand up to greet their liberators. One of these, Harold Le Druillenec, a Channel Islander, had been sent to the camp for sheltering two Russian prisoners-of-war. His sister, Louisa Gould, who had likewise been sent to concentration camp for helping to shelter the two Russians, had been sent to Ravensbrück, where she died.

***

On the day that British tanks first reached Belsen, seventeen thousand women and forty thousand men were being marched westwards from Ravensbrück and Sachsenhausen. A Red Cross official, who was present by chance as the marchers set off from Ravensbrück, wrote in his report: ‘As I approached them, I could see that they had sunken cheeks, distended bellies and swollen ankles. Their complexion was sallow. All of a sudden, a whole column of those starving wretches appeared. In each row a sick woman was supported or dragged along by her fellow detainees. A young SS woman supervisor with a police dog on a leash led the column, followed by two girls who incessantly hurled abuse at the poor women’.

Many hundreds of women died of exhaustion in the march from Ravensbrück. Hundreds more were shot by the wayside. Others were killed by Allied bombs falling on the German lines of communication. Among these bomb victims was Mila Racine, a twenty-one-year-old French girl who, in October 1943, had been caught by the Gestapo while on clandestine courier duty, escorting a group of children to the Swiss border. Later she had been deported to Auschwitz. Now, having survived so long, she lay dead by a German roadside.

From the Rhine to the Elbe, April 1945

***

On April 15, Canadian forces captured Arnhem, scene of the abortive Allied parachutists’ attack seven months earlier. That day, Hitler’s mistress Eva Braun arrived in Berlin to join him in his bunker, telling a friend, as she left the comparative safety of Munich: ‘A Germany without Adolf Hitler would not be fit to live in.’

Beginning on April 15, the German Army launched a counter attack against the Americans, south of Uelzen, hoping to reopen the road for General Wenck’s Army, or at least its remnants, to break out from the Harz Mountains and to join in the battle for Berlin. But it was a forlorn attempt, halted and then driven back by the Americans, who used not only artillery and tanks, but white phosphorous weapons, to end all hope even of a German defensive line. Conscious that this was to be virtually their last battle in Europe, the Americans gave it the code name Operation Kaputt.

Almost all Germany’s ammunition factories and ammunition dumps were now in Allied hands. ‘There may shortly occur the most momentous consequences for our entire war effort,’ Hitler was warned by Alfred Toppe, the Army Quartermaster General on April 15.

***

At five o’clock on the morning of April 16, with the firing of half a million shells, rockets and mortar bombs, the Red Army opened its offensive against Berlin, when three thousand tanks of the highest quality and firepower drove westwards from their bridgeheads over the River Oder. Sixty German suicide planes crashed on the Oder bridges, or as close to them as they could, but were powerless to halt the massive thrust of Soviet troops and armour. On the southern front, Soviet forces, already masters of Vienna, drove westward to St Pölten and Fürstenfeld. In the air above Berlin, American fighters shot down twenty-two German jet aircraft, almost the last jets that were capable of action. From his bunker in Berlin, Hitler issued an Order of the Day to his commanders facing the Red Army: ‘He who gives the order to retreat is to be shot on the spot.’

Pressing into the last German pockets of resistance in the Ruhr, the Americans had taken 20,000 prisoners by April 16. That same day, American forces liberated both Fallingbostel and Colditz, two camps from which Allied prisoners-of-war now joined more than a quarter of a million other prisoners-of-war freed from captivity during April. In Berlin on April 16, Hitler dismissed his personal physician, Germany’s Minister for Health and Sanitation, Karl Brandt; he had just learned that Brandt had sent his wife and child to Thuringia, where they could give themselves up to the Americans.

***

In the Pacific, on April 16, the Americans landed on the small Ryukyu island of Ie Shima. The Japanese suicide planes were still a daily threat to every move at sea; that day, one such attack killed eight crewmen on board the aircraft-carrier Intrepid, which had already lost nearly a hundred men in earlier attacks. Also on April 16, on the Philippine island of Leyte, where some Japanese forces had continued fighting since the American conquest of the island more than three months earlier, the Japanese commander, General Suzuki, was killed, and the resistance dwindled. In the southern Philippines, even on central Luzon, the Japanese had also continued to fight; on April 17, further American forces landed on Mindanao.

Throughout Germany, April 17 saw the collapse of all Hitler’s hopes of holding either the Western or the Eastern Front. In the West, American troops reached the outskirts of Nuremberg, scene of the greatest pre-war Nazi rallies and triumphs; now the city was deluged in a barrage of artillery fire.

In the East, the Red Army crossed the Oder in force, driving towards Berlin, and reaching Seelow. As it did so, 572 American bombers struck for the sixth time at the marshalling yards in Dresden. From his bunker under the Chancellery, Hitler ordered all autobahn bridges in the Berlin area blown up, and declared, at a midday conference of his commanders: ‘The Russians are in for the bloodiest defeat imaginable before they reach Berlin.’

Not the Russians, but the Germans, were on the verge of bloody defeat; on April 17, American bombers destroyed 752 German aircraft on the ground, virtually the last air forces of the Reich. That same day, however, Hitler refused a request by General von Vietinghoff, in Italy, to withdraw his armies northward. Also on April 17, Hitler ordered his armies in the West to attack the weakest points of the Anglo-American flanks and supply lines; on the following day, Field Marshal Kesselring urged the German troops to stand firm in the Harz Mountains.

On April 18, nearly a thousand British bombers struck at German fortifications on the island of Heligoland, in the North Sea. That day, Churchill instructed General Montgomery to make, not for Berlin, but for the Baltic port of Lübeck. ‘Our arrival at Lübeck,’ Churchill told Eden, ‘before our Russian friends from Stettin, would save a lot of argument later on. There is no reason why the Russians should occupy Denmark, which is a country to be liberated and to have its sovereignty restored. Our position at Lübeck, if we get it, would be decisive in this matter’.

On the same theme, Churchill told Eden that it would be ‘well’ for the Western Allies to ‘push on to Linz to meet the Russians there’. He also suggested ‘an American circling movement to gain the region south of Stuttgart before it is occupied by the French’. In this region, Churchill pointed out, were the main German installations connected with ‘their research into “TA”’—Tube Alloys, the atomic bomb—‘and we had better get hold of these in the interests of the special secrecy attaching to this topic.’ These suggestions, Churchill added, ‘are for your own information and as background in deep shadow’.

***

In Burma, on April 18, as part of the plan to recapture Rangoon, a substantial commando force, led by Major Tulloch and a group of British officers, attacked Japanese positions behind the lines. Known as Operation Character, it also provided Intelligence for the bomber forces engaged in the Rangoon offensive, and assisted special groups parachuted into the region, with whom, in a series of joint attacks on troop trains, marching columns and isolated bases, it killed an estimated ten thousand Japanese troops, for the loss of less than sixty of its own officers.

On the island of Ie Shima, off Okinawa, April 18 saw the death of one of America’s most popular war correspondents, Ernie Pyle, killed by a Japanese machine gun bullet. His body was recovered, under fire, by some of the infantrymen whose daily existence in war he had tried to convey to the American public. In his pocket they found the draft of a newspaper column which he had intended to publish at the end of the war in Europe. In it, he wrote of how, in the ‘joyousness of high spirits’ brought about by victory, ‘it is easy for us to forget the dead. Those who are gone would not wish themselves to be a millstone of gloom around our necks. But there are many of the living who have had burned into their brains forever the unnatural sight of cold dead men scattered over the hillsides and in the ditches along the high rows of hedge throughout the world. Dead men by mass production—in one country after another—month after month and year after year. Dead men in winter and dead men in summer. Dead men in such familiar promiscuity that they become monotonous. Dead men in such monstrous infinity that you come almost to hate them’.

Pyle added: ‘These are the things that you at home need not even try to understand. To you at home they are columns of figures, or he is a near one who went away and just didn’t come back. You didn’t see him lying so grotesque and pasty beside the gravel road in France. We saw him, saw him by the multiple thousands. That’s the difference….’

Ernie Pyle was killed six days after Roosevelt’s death. ‘The nation is saddened again’, said President Truman, ‘by the death of Ernie Pyle.’

On April 19, the day after Pyle’s death on Ie Shima, American forces entered Aha, completing their conquest of central and northern Okinawa. But in the south, around Naha, the Japanese prepared to hold the land yard by yard, as they had earlier done on Iwo Jima.

***

On April 19, American troops entered Leipzig. That same day, the Red Army broke through the German defences at Forst, on the River Neisse, seventy-five miles south-east of Berlin. In Bayreuth, the Gauleiter of Bavaria, Fritz Waechtler, was executed that day by the SS on a charge of defeatism. Also on April 19, at Dachau, the SS executed four French and eleven Czech officers, who had been captured several years earlier on clandestine missions in German-occupied France and Czechoslovakia.

Nuremberg, the city of the pre-war Nazi rallies, fell to the Americans on April 20 with 17,000 German soldiers taken prisoner, as, on the Eastern Front, Soviet forces entered Kalau, only sixty miles from Berlin. That day, Hitler celebrated his fifty-sixth birthday, in a Berlin which suddenly reverberated to the sound of Soviet artillery, which had opened fire on the capital at eleven o’clock that morning.

As Hitler’s birthday party progressed, Allied bombers made their last massive raid on his capital. That afternoon, during a lull in the bombing, Hitler came up from his bunker to inspect the teenage soldiers of the Hitler Youth, and older men of a recently formed SS division, which was to defend the capital. Wishing them all well, he returned underground, to a birthday tea-party, at which his guests gained the impression that he was considering the possibility of leaving Berlin for Berchtesgaden, to continue the fight in an Alpine redoubt south of Munich. He also spoke to his guests of his determination to hold both Bohemia—Moravia and Norway. From the German administrators of Norway and Denmark, he had just received a birthday telegram: ‘Norway shall be held!’

Hitler now remained in his bunker, fifty feet below ground, with his staff and secretaries, as Berlin took a daily pounding from Soviet artillery, and as the Red Army drew closer every day. Himmler, who had been one of the guests at the birthday party, made contact later that day with the Swedish Red Cross, and in the hope of favourably impressing the Western Allies, agreed to send seven thousand women, half of them Jews, from Ravensbrück to Sweden.

In Italy, on April 20, in an attempt to cut off the German lines of retreat, Allied bombers launched Operation Corncob, a three-day attack on the bridges over the rivers Adige and Brenta. In Yugoslavia, the last German forces were moving northward through Croatia, towards Zagreb, and on to Austria; among the medals given out on Hitler’s birthday was a War Merit Cross, First Class, with Swords, awarded to Lieutenant Waldheim, for his work on the staff of General Löhr.

Hitler’s birthday also saw a continuation of the terror which had made his rule hated throughout Europe. That day, at Bullenhuser Damm, near Neuengamme, the Gestapo hanged a Dutchman, Anton Holzel, from the town of Deventer. Holzel had earlier been arrested for distributing underground Communist newspapers. Also killed on Hitler’s birthday, by hanging, were twenty Russian prisoners-of-war, and twenty Jewish children, each of whom had earlier been taken from Auschwitz to Neuengamme for medical experiments. British forces were already a few miles away, at Harburg. Before they reached Bullenhuser Damm, the bodies of both the adults and the children had been taken to Neuengamme and cremated.

Seven of the twenty children have never been identified. The thirteen whose names are known included two five-year-olds, Mania Altman and Eleonora Witonska, as well as Eleonora Witonska’s seven-year-old brother Roman, and the seven-year-old Rywka Herszberg, all from Poland. Also murdered were the seven-year-old Sergio de Simone from Italy; the eight-year-old Alexander Hornemunn from Holland and his twelve year-old brother Eduard; and two twelve-year-olds from France, Jacqueline Morgenstern and Georges André Kohn, who had been on the very last of the deportations from Paris, in August 1944.

***

In Germany, on April 21, French forces entered Stuttgart. In Italy, Polish forces entered Bologna. That same day, the Germans launched an anti-partisan sweep in the region around Gorizia; more than 170 Italian partisans were killed. In Berlin, where Soviet troops had now reached the extreme southern and eastern suburbs, Hitler ordered SS General Steiner to move north to Eberswalde, break through the Soviet flank and re-establish the German defences to the north-east of Berlin. ‘You will see’, he told Steiner, ‘the Russians will suffer the greatest defeat of their history, before the gates of Berlin,’ but he went on to warn his General: ‘It is expressly forbidden to fall back to the West. Officers who do not comply unconditionally with this order are to be arrested and shot immediately. You, Steiner, are answerable with your head for execution of this order.’

In what was once the Ruhr pocket, 325,000 German troops, including thirty generals, had surrendered by April 21; that day, their commander, Field Marshal Model, shot himself in a forest between Düsseldorf and Duisburg.

In the British zone of battle, in the village of Wistedt, between Bremen and Hamburg, April 21 saw a twenty-four-year-old Guardsman, Edward Colquhoun Charlton, win the last Victoria Cross of the war in Europe, for saving the lives of several men who had been trapped in their tank. He himself was so badly wounded that he died shortly after being taken prisoner. His principal adversary in this battle, Lieutenant Hans-Jürgen von Bulow, was awarded the Iron Cross, First Class.

To the south of Berlin, during April 21, the Red Army reached, and overran, the headquarters of the German High Command, at Zossen. The chief opposition now to the Soviet entry into Berlin were small ‘battle groups’ of Hitler Youth, teenage boys with anti-tank guns which had been placed in parks and prominent buildings and suburban streets. At Eggersdorf, on April 21, seventy such defenders with three anti-tank guns between them, were typical of the last minute efforts to keep the Russians out of Berlin. They were mown down by tanks and infantry.

Heinrich Himmler was now in command of both the Rhine and Vistula armies. On April 22, at a further meeting with Count Folke Bernadotte, this time in Lübeck, he offered to surrender to the Western Allies, but not to the Russians. Germany would continue fighting the Russians, Himmler explained, ‘until the front of the Western powers has replaced the German front’. The Western powers had no intention, however, of turning against Russia; they would allow no separate negotiations, only a surrender without conditions: total and complete surrender of all armies on all fronts. Until the German surrender, Churchill assured Stalin—in reporting Himmler’s approach—‘the attack of the Allies upon them, on all sides and in all theatres where resistance continues, will be prosecuted with the utmost vigour’.

Inside Greater Germany, the imminence of defeat led to the first relaxation of concentration camp security. On April 22, when two Swiss representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross reached Mauthausen with trucks and food, they were allowed to take away with them 817 French, Belgian and Dutch deportees.

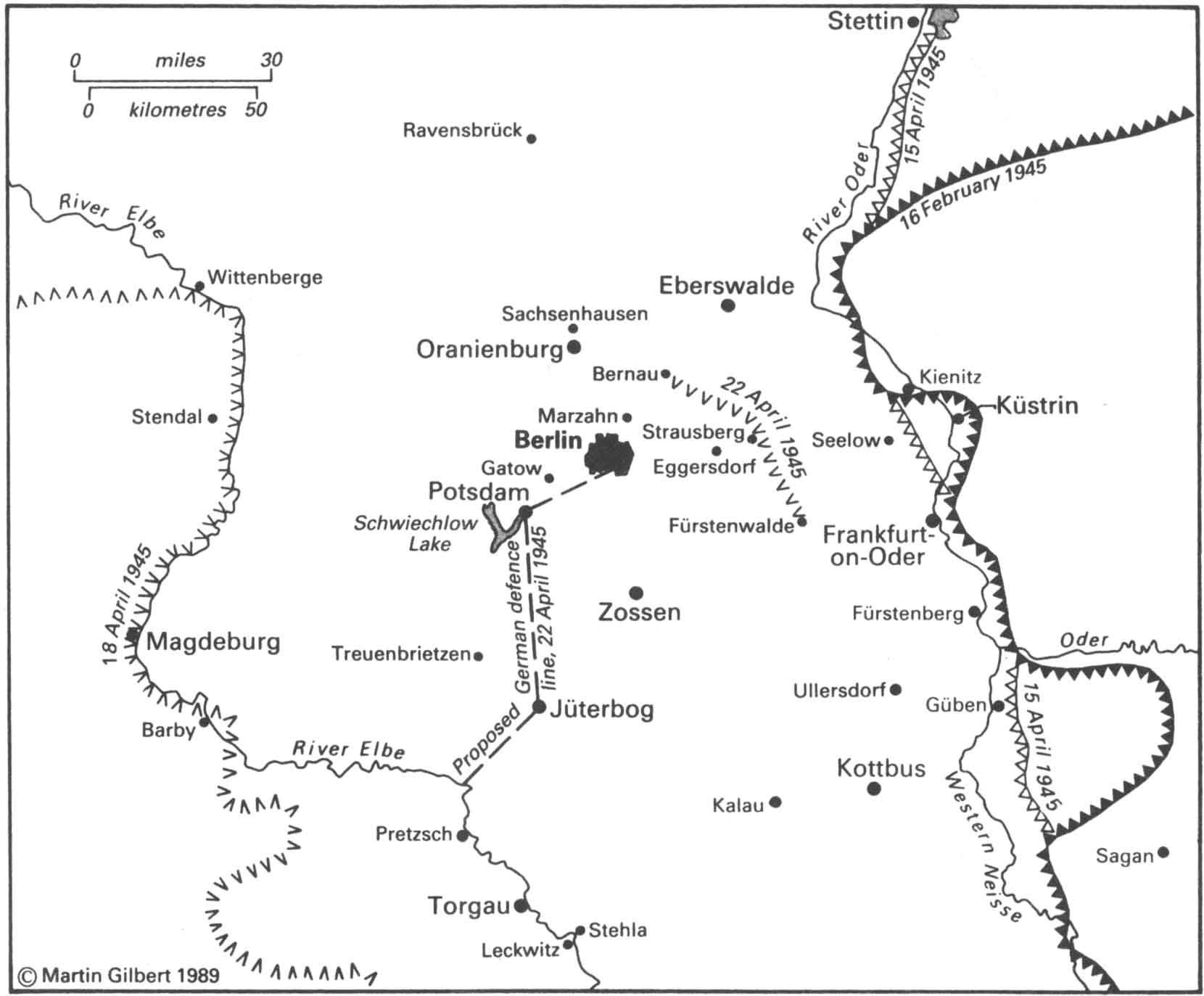

In his bunker on April 22, Hitler learned that General Steiner had failed to move a single man to attack the Russians at Eberswalde. He at once told those who were with him in the bunker that the war was lost. All thought of an Alpine redoubt south of Munich was abandoned. He would remain in Berlin, Hitler declared, and would shoot himself when the end came. Hitler’s entourage were appalled; General Jodl, in a burst of optimism quite at variance with the reality of the situation, spoke of new military moves designed to defend Berlin, declaring that the Army on the Elbe, which faced the British and Americans, could be brought eastward to hold a defensive line from the Elbe, to Jüterbog and Potsdam.

The battle for Berlin, March–April 1945

That same day, however, a Soviet mechanized corps reached Treuenbrietzen, forty miles south-west of Berlin and fifteen miles west of Jodl’s proposed defence line; there, they found a prisoner-of-war camp, in the liberation of which a Red Army officer, Lieutenant Zharchinski, was killed while breaking through the camp defences. Among those freed that day was Major General Otto Ruge, the former Commander-in-Chief of the Norwegian Army, who had been captured by the Germans five years earlier.

From Treuenbrietzen, the Soviet mechanized corps moved eastward to Jüterbog, reaching an aerodrome on which it found 144 damaged aircraft, 362 aircraft engines without aircraft, and three thousand bombs. Long before Jodl’s plan for German forces to regroup at Jüterbog could be put into action, the town was in Soviet hands, and a Soviet ring established to the south and south-west of the capital.

To the north-east and east of Berlin, Soviet troops now stood on the line Fürstenwalde—Strausberg—Bernau. That night, at the Prinz Albrechtstrasse Prison in Berlin, an SS firing squad shot Rüdiger Schleicher, whose office at the Institute for Aviation Law at the University of Berlin had been a meeting place for German anti-Nazis, including his brothers-in-law, Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Hans von Dohnanyi, both of whom had already been executed.

In Yugoslavia, German troops were falling back to Zagreb: on April 22 they were still in control of the region of Jasenovac, the concentration camp in which tens of thousands of Serbs and Jews had been murdered. Only a thousand inmates were still alive. Fearful that they would be murdered on the eve of the German retreat, they rose up in revolt. Six hundred of them turned on their guards; more than five hundred of them were shot down. But sixty of the Serbs, and twenty of the Jews, escaped—yet more witnesses of barbarities, the full details of which were yet to be made known to a world which was suddenly becoming exposed to tales of previously unimagined barbarity.

***

On April 23, Hitler assumed personal command of the defence of Berlin. Policemen, members of the Hitler Youth, old men, and women of all ages, were enlisted to help keep the Russians from entering the capital. That day, Goering sent Hitler a telegram proposing, as Hitler’s current deputy, to assume full control of Germany. ‘If no reply is received by ten o’clock tonight,’ Goering added, ‘I shall take it for granted that you have lost your freedom of action.’

Hitler at once dismissed Goering from all his offices of State, and ordered his arrest. In Goering’s place as head of the German Air Force, Hitler decided to appoint Robert Ritter von Greim, one of Germany’s most highly decorated pilots, and, since February 1943, commander of the German Air Force on the Eastern Front. Greim, who was then in Munich, was summoned to Berlin.

In Berlin, during April 23, two more of the imprisoned conspirators were executed: Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s brother Klaus, and the geographer and writer Albrecht Haushofer, who had wished to see a restoration of the monarchy once Hitler was overthrown.

***

In Belsen, on April 23, eight days after the camp’s liberation, one of the hundreds of emaciated former prisoners who died that day was a Frenchwoman, Yvonne Rudellat, who, as the British agent ‘Jacqueline’, had been smuggled by boat into France in July 1942, and who had been arrested eleven months later.

***

In Italy, Allied forces had crossed the River Po, and on April 24, the Italian Committee for National Liberation ordered a general uprising through the areas still under German control. German columns in retreat were everywhere attacked, and on April 25, Italian partisans liberated Milan. That morning, more than three hundred British bombers attacked Hitler’s Berghof headquarters at Berchtesgaden; Goering, who was already under arrest in his home on the mountain, was unhurt, but many buildings were badly damaged, and six people killed.

As British bombs fell on Berchtesgaden, General Ritter von Greim flew from Munich to Berlin. With him was Hanna Reitsch, one of Germany’s leading test pilots, and advocate of a pilots’ suicide squad. On the last lap of their journey, von Greim flew a tiny plane from Gatow to the Chancellery, with Hanna Reitsch stuffed into the tail of the plane. During the flight, von Greim was injured in the foot by Russian anti-aircraft fire; Hanna Reitsch managed to lean across him and land the plane a few hundred yards from Hitler’s bunker.

In the bunker’s surgery, while von Greim’s wound was being dressed, Hitler told the astonished airman: ‘I have called you because Hermann Goering has betrayed both me and the Fatherland. Behind my back he has made contact with the enemy. I have had him arrested as a traitor, deprived him of all his offices, and removed him from all organizations. That is why I have called you.’

Hitler then informed von Greim that he was the new Commander-in-Chief of the German Air Force, and a Field Marshal.

That same day, April 25, Hitler ordered the arrest of General Karl Weidling, commander of a panzer corps, accusing him of desertion. Weidling, whose troops were in fact still defending the outskirts of Berlin, hurried to the bunker and protested his innocence; Hitler then appointed him ‘Battle Commandant’ of Berlin itself. Eight Soviet armies were now closing in on the city. But the most dramatic development of April 25 came shortly after midday, when an American Army officer, Lieutenant Albert Kotzebue, moving forward near the village of Leckwitz, on the western bank of the Elbe, met a solitary Soviet soldier. Crossing the river, Lieutenant Kotzebue met more Soviet soldiers, encamped near the village of Stehla. The Soviet and American armies had linked up. Germany was cut in two. Four hours later, ten miles north-west of Stehla, another American patrol, led by Lieutenant William D. Robinson, came upon yet more Soviet soldiers at the village of Torgau.

The Allies rejoiced to have linked forces. Himmler’s last minute hopes of turning one against the other were utterly broken. In Moscow, 324 guns fired a twenty-four salvo in celebration of the Torgau meeting. In New York crowds danced and sang in Times Square.

As the Americans and Russians joined forces on the Elbe, the French Army was sweeping through Württemberg. On April 25 it reached the upper Danube village of Tuttlingen, where it found the mass grave of eighty-six Jews, brought there six months earlier from ghettos in the East, and killed. In four other villages in the region, including Schomberg and Schörzingen, a further 2,440 bodies were found. That same day, in the Italian town of Cuneo, the Gestapo shot six Jews. At Ravensbrück, April 25 saw the execution of Anna Rizzo, who, with her husband, had helped organize one of the largest Allied escape and evasion lines through France, the ‘Troy’ line. At Johanngeorgenstadt that day, the Gestapo executed Paul d’Ortoli, the town clerk of the small French village of Contes, who had been arrested in October 1943.

***

In the Pacific, the struggle for Okinawa continued. At the same time, American bombers intensified their attacks on the Japanese islands, hoping to create the disruption needed for a successful invasion, planned for that November. But on April 25, the Secretary for War, Henry L. Stimson, went to see President Truman with news which could conceivably alter the whole timetable of the final assault on Japan. ‘Within four months’, Stimson told Truman, ‘we shall in all probability have completed the most terrible weapon ever known in human history, one bomb of which could destroy a whole city.’

***

The Berlin defence perimeter, which Hitler had ordered to be held at all cost, was now pierced in the north, the east and the south east. The suburbs of Moabit and Neukölln were both in Russian hands by nightfall on April 26. That same day, British Intelligence decrypted a top-secret message, sent to Himmler by the SS, warning that food for the civilian population still under German control would not last beyond May 10. On the day of this message, Russian forces, entering Potsdam, completed the encirclement of Berlin. German forces in the city were now restricted to an area less than ten miles long from west to east, and only one to three miles wide. That day, unaware that Hitler had decided never to leave Berlin, units of the Red Army seized his last avenue of escape, the airfield of Tempelhof.

Camp after camp was now being liberated; not far from Berlin, Soviet forces freed Edouard Herriot, a former Prime Minister of France. At Landsberg, where Hitler had been imprisoned for just over a year in 1923 and 1924, an American officer, Colonel Yevell, secured one of the strangest trophies of the war, the plaque above the door of Hitler’s former prison cell. ‘Here’, it read, ‘a dishonourable system imprisoned Germany’s greatest son from November 11, 1923 to December 20, 1924. During this time Adolf Hitler wrote the book of the National Socialist Revolution, Mein Kampf.’ Today, the plaque is on display in the Kentucky Military Museum at Frankfort, Kentucky.

In the Landsberg region, the Americans found six concentration camps; German civilians living near by were forced to bury the hundreds of emaciated corpses that lay on the barren, filthy ground. Thousands of slave labourers were also liberated around Landsberg, including Russians, Poles, Yugoslavs and Frenchmen.

The days of liberation were also days of massive casualties, as German units, especially those facing the Red Army, refused to abandon the battlefield. On April 26, after a prolonged battle, Soviet forces captured the Moravian city of Brno, and drove on northward to Olomouc; 38,400 Red Army men had been killed in the Czechoslovak campaign. In Berlin, three-quarters of the city was in Soviet hands by the end of April 27. Near Zossen, Red Army troops foiled an attempt by the German Ninth Army to fight its way back to Berlin.

At Marienbad, in western Czechoslovakia, a thousand Jews, originally from Buchenwald, and on the road for nearly two weeks, were killed on April 27 by machine gun fire and grenades; their guards had turned on them at Marienbad railway station. That same day, at Mauthausen, Himmler’s deputy, Kurt Becher, was told by the camp Commandant that Ernst Kaltenbrunner, the head of the Security Service, ‘instructed me that at least a thousand men must still die every day in Mauthausen’.

That April 27, in Turin, Italian partisans took up arms against the Germans, as they had done two days earlier in Milan. Among the partisans killed that day in Turin was a young Jew, Giorgio Latis, whose mother, father and sister had been deported to Auschwitz the previous September, and never heard of again. That same day, in the Baltic Sea, off Rostock, several thousand Jewish women from Stutthof concentration camp, who had been evacuated by sea a week earlier, were caught in an Allied bombing raid; five were killed. The SS and Ukrainian guards who were accompanying them on board, had already thrown overboard several hundred of the sick and injured, mostly women from Kovno and Lodz ghettos. On April 28, in a second Allied bombing raid, several hundred women were killed.

Berlin besieged, April 1945

***

President Truman and his advisers now discussed what city the atomic bomb should be dropped on; a special Target Committee was looking for one which had not already been badly damaged. Although Tokyo was a ‘possibility’, the Committee wrote on April 27, ‘it is now practically all bombed and burned out, and is practically rubble with only the Palace grounds left standing’. The committee concluded: ‘Hiroshima is the largest untouched target not on the 21st Bomber Command list. Consideration should be given to this city’.

***

In Berlin, a motley crew of defenders still tried to keep the Russians from the inner city. One such defender, Reginald Leslie Cornford, was a British volunteer in the British Free Corps. Hiding in a church, on April 27 he knocked out a Russian tank with his anti-tank gun; then defended himself for half an hour, before being killed. On the following day, a French SS volunteer, Eugene Vaulot, destroyed six Russian tanks; he was awarded the Knight’s Cross.

During April 28, a Red Army rifle regiment, commanded by Colonel Zinchenko, seized the Moabit Prison, on the edge of the Tiergarten; seven thousand prisoners, including many Allied prisoners-of-war, were released. Within a few hours, Soviet troops were fighting in the Tiergarten itself. Not only the sound of battle, but its acrid fumes, now penetrated Hitler’s bunker. From the bunker, orders were still flowing, including one to General Wenck, who, with a few shattered remnants of the men he had managed to bring away from encirclement in the Harz Mountains, had been ordered to advance to Berlin. But there were now fewer and fewer people who were either able or willing to obey the new spate of orders. That day, General Gotthard Henrici, Himmler’s successor as Commander of the Vistula Army Group, was dismissed for not having carried out a ‘scorched earth policy’ in front of the advancing Russians. When General Weidling proposed that all those in the central area, and in Hitler’s bunker, break out to the West of the city, Hitler refused. Only the newly promoted Field Marshal von Greim was allowed to leave, ordered to do so by Hitler, in order, not to reactivate the shattered German Air Force, but to arrest Himmler, whose negotiations with the Allies had become known in the bunker that afternoon. ‘A traitor must never succeed me as Führer,’ Hitler declared.

Now anyone close to Himmler was suspect. On April 26, Eva Braun’s brother-in-law, Hermann Fegelein, Himmler’s representative in the bunker, had slipped away, unnoticed, to his home in the Charlottenburg district of Berlin, itself now partly under Russian control. But on April 28, Hitler noticed Fegelein’s absence, and an armed SS search party was sent to find him. Brought back to the bunker, he was stripped of his SS lieutenant-general’s rank, taken into the Chancellery yard, and shot.

***

In Italy, April 28 saw the ignominious end to the Fascist rule which had begun twenty-three years earlier; for on that day, near the lakeside village of Dongo, Mussolini was shot dead by Italian partisans. Also shot, in reprisal for the killing of fifteen Italian partisans in Milan nine months earlier, were fifteen of those who had been captured with Mussolini, including Alessandro Pavolini, the Secretary of the Fascist Party, four Cabinet Ministers, and several of Mussolini’s friends. His mistress, Clara Petacci, was also shot. Her body, and that of Mussolini, were taken to Milan and hanged there, upside down, on the morning of April 29. Early that afternoon, at Caserta, General von Vietinghoff’s representatives signed the unconditional surrender of all German troops in Italy.

***

As Mussolini’s body was being taken from Dongo to Milan, Hitler, in his bunker in Berlin, was writing his political testament and making plans to marry Eva Braun. In his testimony, he explained how much her loyalty, and her decision to stay with him in the bunker, had meant to him. He also wrote that he was expelling both Goering and Himmler from the Nazi Party, and announced the setting up of a new Government, with Admiral Dönitz as President and Dr Goebbels as Chancellor.

Much of Hitler’s testimony consisted of his reflections on the origins of the war. Neither he, nor ‘anyone else in Germany’, he wrote, had wanted a second war against Britain and America, and he went on to explain: ‘Centuries will go by, but from the ruins of our towns and monuments the hatred of those ultimately responsible will always grow anew against the people whom we have to thank for all this: international Jewry and its henchmen.’

Hitler then declared that the war had been caused solely by those international statesmen ‘who either were of Jewish origin or worked for Jewish interests’. The Jews were ‘the real guilty party in this murderous struggle’ and would be ‘saddled’ with the responsibility for it. Hitler added: ‘I left no one in doubt that this time not only would millions of children of European Aryan races starve, not only would millions of grown men meet their death, and not only would hundreds of thousands of women and children be burned and bombed to death in cities, but this time the real culprits would have to pay for their guilt even though by more humane means than war’.

The ‘more humane means’ had been the gas chambers.

Stating that he could not ‘abandon’ Berlin, and that the city’s resistance was being ‘debased by creatures who are as blind as they are lacking in character’, Hitler explained that he wished to share his fate ‘with that which millions of others have also taken upon themselves by remaining in this city’. He had therefore decided to stay in Berlin ‘and there to choose death voluntarily when I determine that the position of the Führer and the Chancellery itself can no longer be maintained. I die with a joyful heart in the knowledge of the immeasurable deeds and achievements of our peasants and workers and of a contribution, unique in history, of our youth which bears my name’.

Hitler added: ‘Through the sacrifices of our soldiers and my own fellowship with them unto death, a seed has been sown in German history that will one day grow to usher in the glorious rebirth of the National Socialist movement in a truly united nation.’

After setting out the names of the members of the new Government, Hitler ended his testimony with one more denunciation of the Jews. ‘Above all,’ he concluded, ‘I enjoin the Government and the people to uphold the race laws to the limit and to resist mercilessly the poisoner of all nations, International Jewry.’

What those race laws had led to was once again brutally revealed, later that same day, when, shortly after three o’clock in the afternoon, American forces entered Dachau. An inmate in the camp, the Belgian doctor and British agent, Albert Guérisse, later recalled how, as the first American officer, a major, descended from his tank, ‘the young Teutonic Lieutenant, Heinrich Skodzensky, emerges from the guard post and comes to attention before the American officer. The German is blond, handsome, perfumed, his boots glistening, his uniform well-tailored. He reports, as if he were on the military parade grounds near Unter den Linden during an exercise, then very properly raising his arm he salutes with a very respectful “Heil Hitler!” and clicks his heels. “I hereby turn over to you the concentration camp of Dachau, 30,000 residents, 2,340 sick, 27,000 on the outside, 560 garrison troops”.’

The American major did not return the German lieutenant’s salute. ‘He hesitates for a moment’, Albert Guérisse later recalled, ‘as if he were trying to make sure that he is remembering the adequate words. Then, he spits into the face of the German, “Du Schweinhund!” And then, “Sit down here!”—pointing to the rear seat of one of the jeeps which in the meantime have driven in. The major turns to me and hands me an automatic rifle. “Come with me”. But I no longer had the strength to move. “No, I stay here—” The major gave an order, the jeep with the young German officer in it went outside the camp again. A few minutes went by, my comrades had not yet dared to come out of their barracks, for at that distance they could not tell the outcome of the negotiations between the American officer and the SS men. Then I hear several shots’.

Lieutenant Skodzensky was dead. Within an hour, all five hundred of his garrison troops were to be killed, some by the inmates themselves, but more than three hundred of them by American soldiers who had been literally sickened by what they saw of rotting corpses and desperate, starving inmates. In one incident, an American lieutenant machine-gunned 346 of the SS guards after they had surrendered, and were lined up against a wall. The lieutenant, who had entered Dachau a few moments earlier, had just seen the corpses of the inmates piled up around the camp crematorium, and at the railway station.

None of those who saw Dachau in the days after its liberation were to forget its horrors. As at Belsen two weeks earlier, the Allied journalists accompanying the troops were shattered by what they saw. Sam Goldsmith, a Jewish journalist from Lithuania who had gone to Britain before the war, and who had earlier been at Belsen, noted down his first sight of Dachau: ‘On a railway siding there is a train of fifty wagons—all full of terribly emaciated dead bodies, piled up like the twisted branches of cut-down trees. Near the crematorium—for the disposal of the dead—another huge pile of dead bodies, like a heap of crooked logs ready for some infernal fire. The stench is like that of Belsen; it follows you even when you are back in the Press camp’.

There were 2,539 Jews among the 33,000 survivors in Dachau. Of those survivors, 2,466 were to die in the following month and a half.

Everywhere, the SS troops continued to fight with fear of capture ever balancing the desire to live. At Dachau itself, as many as thirty guards had been killed when they opened fire on the Americans from the camp watchtowers. That same day, less than five miles away, at Webling, after an American soldier had been killed by SS sniper fire, all seventeen SS men who then surrendered were lined up against an earthen bank, and shot.

The only mercy on April 29 came from the air, when three thousand British bombers launched Operation Manna, parachuting more than six thousand tons of supplies to the Dutch behind German lines in Rotterdam and The Hague, where shortages of food were leading to starvation throughout German-occupied Holland. In all, 16,000 Dutch civilians starved to death.

In Berlin, General Weidling reported to Hitler on the evening of April 29 that the Russians had reached the nearby Potsdam Station. In addition, there were no longer any anti-tank guns available for the defence of the Chancellery area. What, asked Weidling, were his men to do once they had run out of ammunition? ‘I cannot permit the surrender of Berlin,’ Hitler replied. ‘Your men will have to break out in small groups.’

That afternoon, the Citadel Commandant of Hitler’s bunker, SS Major-General Mohnke—who in 1940 had been the senior officer involved in the massacre of British prisoners-of-war at Paradis, near Dunkirk—made the last two presentations of the Knight’s Cross. One was to the French SS volunteer, Eugene Vaulot, for destroying six Russian tanks on the previous day, the other was to the commander of the tank troops defending the Chancellery, Major Herzig. That night, at eleven o’clock, Hitler telegraphed from the bunker: ‘Where are Wenck’s spearheads? When will they advance? Where is the Ninth Army?’ British cryptographers at Bletchley, ever-vigilant, read these last desperate questions on their Enigma machine.

At one o’clock on the morning of April 30, Field Marshal Keitel informed Hitler that General Wenck’s forces were ‘stuck fast’ south of the distant Schwiechlow Lake, and had no way of moving towards the capital, while the Ninth Army was completely encircled.

As Hitler, in Berlin, contemplated the imminent destruction of his capital and his life’s work, Churchill, in London, was looking with anguish as Stalin imposed full Soviet control on Poland. ‘I have been much distressed’, Churchill telegraphed to Stalin on April 29, ‘at the misunderstanding that has grown up between us on the Crimean Agreement about Poland.’ Britain and America had agreed to allow the Lublin Government to become a ‘new’ Government, ‘recognized on a broader democratic basis with the inclusion of democratic leaders from Poland itself and from Poles abroad’. For this purpose, a Commission had been set up in Moscow ‘to select the Poles who were to come for consultations’. Britain and America had excluded from their nominees those who they thought ‘were extreme people unfriendly to Russia’. They had not selected anyone ‘at present in the London Government’, but chose instead ‘three good men’ who had earlier gone into opposition to the London Government ‘because they did not like its attitude towards Russia, and in particular its refusal to accept the eastern frontier’, the Curzon Line, ‘which you and I agreed upon, now so long ago, and which I was the first man outside the Soviet Government to proclaim to the world as just and fair’, together with the territorial compensations for Poland in the west and north.

Churchill went on to point out to Stalin that not one of the three British and American nominees had been invited to Moscow to come before the Commission. As to the plan, agreed upon at Yalta, to establish a government based on ‘universal suffrage and secret ballot’, with all the democratic and anti-Nazi parties having the right to take part and put forward candidates, ‘none of this has been allowed to move forward’. The Soviet Government had signed a Twenty Years’ Treaty with the former Lublin Committee, now called by Stalin the ‘new Government’ of Poland, ‘although it remains neither new nor reorganized’.

‘We have the feeling’, Churchill wrote, ‘that it is we who have been dictated to and brought up against a stone wall upon matters which we sincerely believed were settled in a spirit of friendly comradeship in the Crimea.’ He went on, after referring to the Communist predominance in the Yugoslav Government with which Stalin had just signed a treaty, to tell the Soviet leader, with deep foreboding: ‘There is not much comfort in looking into a future where you and the countries you dominate, plus the Communist Parties in many other States, are all drawn up on one side, and those who rally to the English-speaking nations and their associates or Dominions are on the other. It is quite obvious that their quarrel would tear the world to pieces and that all of us leading men on either side who had anything to do with that would be shamed before history’.

Churchill’s telegram to Stalin continued: ‘Even embarking on a long period of suspicions, of abuse and counter-abuse and of opposing policies would be a disaster hampering the great developments of world prosperity for the masses which are attainable only by our trinity. I hope there is no word or phrase in this outpouring of my heart to you which unwittingly gives offence. If so, let me know. But do not, I beg you, my friend Stalin, under-rate the divergencies which are opening about matters which you may think are small to us but which are symbolic of the way the English-speaking democracies look at life’.

***

On the morning of April 30, American troops entered Munich; in Italy, they entered Turin. That same day, General Eisenhower informed the Soviet Deputy Chief of Staff, General Antonov, that American troops would not advance further into Austria than the ‘general area of Linz’ and the River Enns. In Istria, British and American forces hurried to reach Fiume, Pola and Trieste before Tito did. Churchill, angered by Eisenhower’s promise to Antonov, and fearful of the westward march of Communism to the Adriatic, telegraphed to Truman on April 30: ‘There can be little doubt that the liberation of Prague and as much as possible of the territory of Western Czechoslovakia by your forces might make the whole difference to the post-war situation in Czechoslovakia, and might well influence that in nearby countries. On the other hand, if the Western Allies play no significant part in Czechoslovakian liberation that country will go the way of Yugoslavia’.

To Churchill’s disappointment, Truman replied that he would leave the tactical deployment of troops to the military. In passing on the British request that United States forces liberate Prague, General Marshall told Eisenhower: ‘Personally and aside from all logistic, tactical or strategical implications, I would be loath to hazard American lives for purely political purposes.’

Prague was to be liberated by the Red Army, and Istria by Tito’s partisans; there was nothing Churchill could do to prevent these developments. The same day, April 30, in Berlin at half-past two in the afternoon, a Red Army soldier, Sergeant Kantariya, waved the Red Banner from the second floor of the Reichstag. German troops were still on the floor above. Less than a mile away, Hitler was in his bunker, all hope of a counter-attack long abandoned. At half-past three that afternoon, having finished his lunch, he sent those who were with him—Goebbels, Bormann, and his personal staff—out into the passage. As they stood there, they heard a single shot. Hitler had shot himself in the mouth.

Waiting for a few moments, Goebbels, Bormann and the others entered Hitler’s room. The Führer was dead. So too was Eva Braun; she had swallowed poison.

With a single pistol shot, the Thousand Year Reich was at an end, in ignominy, a mere twelve years since it had been launched in triumph. It had been twelve years of bloodshed, war and evil on a scale which almost defies imagination. As Soviet shells still fell around the Chancellery, Hitler’s body, and that of Eva Braun, were taken up from the bunker to the courtyard above, doused in petrol, and set on fire.

At ten minutes to eleven that night, the Red Banner flew on the roof of the Reichstag.