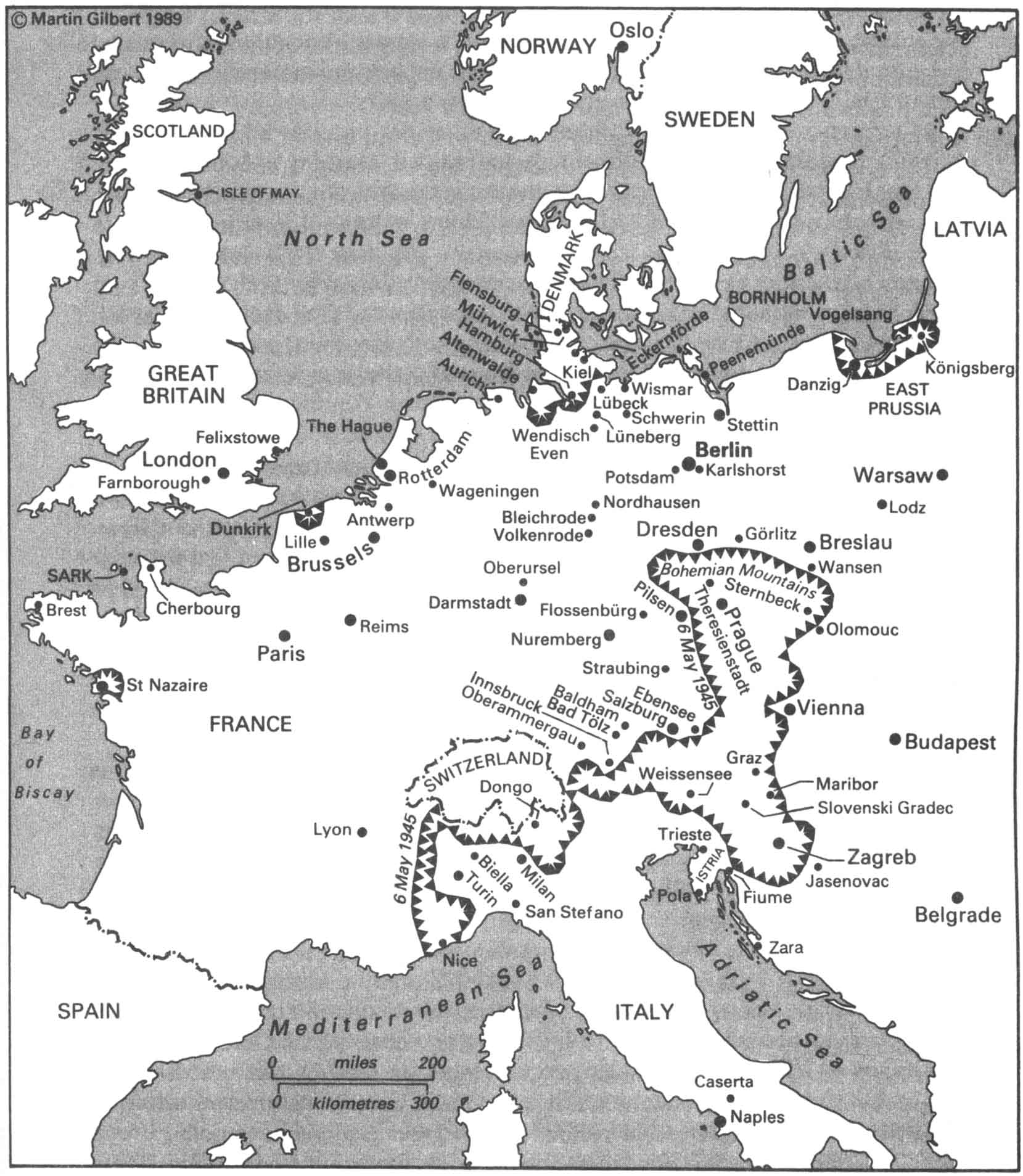

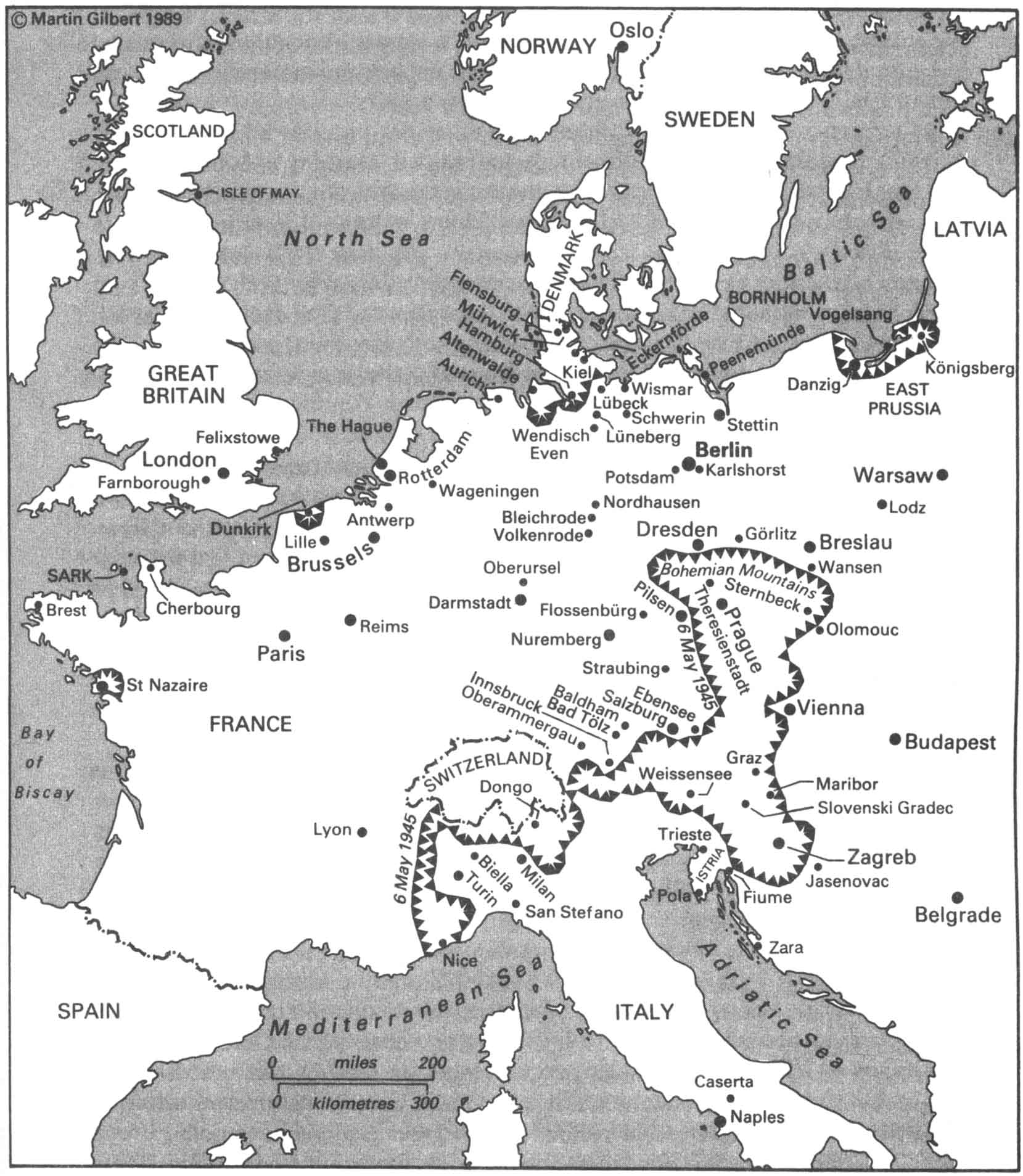

Europe from war to peace, May 1945

Hitler was dead, but the war in Europe still had eight days to run; eight days of battle, death, confusion, fear, exhilaration and exhaustion. On 1 May 1945, the German garrison in Rhodes surrendered. That day, in Berlin, negotiations began between General Krebs and General Zhukov. Krebs asked for a truce. Zhukov insisted upon unconditional surrender. Krebs returned to the bunker, where he found Martin Bormann, the Head of the Nazi Party Chancellery, and Goebbels, both determined not to give in. General Weidling, however, decided that there was no option but to surrender, and, on his own initiative, issued an order to his garrison troops, and to the people of Berlin, to cease all resistance.

Inside the bunker, Goebbels arranged for his six children to be poisoned with a lethal injection by an SS doctor; then he had his wife Magda and himself shot by an SS orderly. General Krebs committed suicide. Bormann tried to escape, but was most probably killed within a mile or so of the bunker.

Another of those who committed suicide on May 1 was Professor Max de Crinis, one of the main advocates of the euthanasia programme at the beginning of the war; it was he who was thought to have provided Hitler with the actual wording of the Euthanasia Decree of September 1939.

***

In the Far East, May 1 saw the launching of Operation Dracula, a British attempt to recapture Rangoon. In one skirmish, where thirty Japanese resisted a Gurkha parachute unit, only a single wounded Japanese soldier survived. But the Japanese had decided not to fight in Rangoon itself; a British pilot, flying over the city that morning, saw written in large letters above the Royal Air force prisoner-of-war camp the words: ‘Japs gone. Exdigitate.’ The British forces did indeed ‘pull their finger out’, and within seventy-two hours Rangoon was liberated.

During Operation Dracula, British bombers flew from their base at Salboni, east of Calcutta, to bomb Japanese military targets around Rangoon, breaking their near-thousand-mile journey at Baranga Island. On board one of these bombers, on its second flight to Rangoon in twenty-four hours, was Wing Commander James Nicolson, the only fighter pilot to have won the Victoria Cross during the Battle of Britain. Now in charge of training at South East Air Force headquarters, he had been selected as a prospective candidate at the next British General Election. On the flight to Baranga, however, the bomber crashed into the sea; Nicolson and nine of the eleven crew members were drowned.

In Borneo, on May 1, Australian troops landed on Tarakan Island; after eighteen days, the Japanese were defeated. But on Luzon and Mindanao in the Philippines, and on Okinawa, continued Japanese resistance made the capture of every mile a fierce and bloody struggle.

***

At a quarter to seven on the morning of May 2, Marshal Zhukov accepted the surrender of Berlin; the ceasefire came into effect at three o’clock that afternoon. That day, the Red Army took 134,000 German soldiers prisoner. Also on May 2, the Mayor of Hamburg began negotiations for the unconditional surrender of the city. That evening, Churchill told the House of Commons that more than a million German troops had now laid down their arms in northern Italy and southern Austria.

In the northern Italian village of Biella, the German soldiers were astounded to see that the American tank crews who entered the village after the German surrender were Japanese; members of a Japanese—American Task Force of American-born Japanese who had fought throughout the Italian campaign. Also surrendering to the Western Allies on May 2, at Oberammergau, in southern Germany, was Dr Herbert Wagner, a guided missile designer. With him were two senior members of the Peenemünde rocket research staff, Wernher von Braun and General Walter Dornberger. All three were hurried to Paris, and then to the United States. ‘We were interested in continuing our work’, von Braun later wrote, ‘not just being squeezed like a lemon and then discarded.’

On May 2, a German bomber, piloted by Lieutenant Rolf Kunze, left the German air base at Trondheim in northern Norway, ostensibly for the even more northerly air base at Bardufoss. It flew instead across the North Sea to Britain, where Kunze and his four fellow-airmen sought asylum. By chance, they landed their plane a few miles from Fraserburgh, in Scotland, not far from where the first German aircraft to be shot down over Britain in October 1939 had crash-landed. Theirs was the first wartime defection of an armed German bomber.

In Dublin, on May 2, the President of Eire, Eamon de Valera, called on the senior German diplomat in the capital, to express his condolences on the death of Hitler. Eire had preserved a tenacious neutrality through more than five and a half years of war.

In Lübeck harbour, still controlled by the Germans, May 2 saw the attempt to transfer 850 Jewish women who had earlier been evacuated by sea from Stutthof, to three large ships in the harbour, the Cap Arcona, the Athena and the Thielbeck. The captains of these ships refused to take them, however; between them, they already had more than nine thousand Jews, political prisoners and Russian prisoners-of-war on board. The small boats were ordered back to the shore. But, as they neared land in the early hours of May 3, and the starving Jews tried to clamber ashore, SS men, Hitler Youth and German marines opened fire on them with machine guns. More than five hundred were killed. Only three hundred survived.

As the British bombardment of Lübeck harbour continued, all two thousand prisoners on board the Athena had managed to get ashore. Of the 2,800 on board the Thielbeck, however, only fifty were saved. Of the five thousand men on the Cap Arcona, which was first set on fire and then sunk by British bombs, only 350 were saved. On the lowest deck, seven hundred gravely ill and dying men were burned to death. Several hundred Russian prisoners-of-war had been put into the ship’s banana coolers; most of them perished.

A Jewish girl born in Lodz, who had survived all the travails of Hitler’s war against the Jews, and who was one of the fifty survivors rescued that day from the Thielbeck and picked up by another German boat, later spoke of the last stage of the journey of the survivors, from Lübeck to Kiel. ‘We kept hearing deafening bombardments along the way,’ she recalled, ‘and fantastic explosions lighting up the horizon. We saw countless numbers of burning ships and huge cargo steamers packed full of people everywhere we passed. The soldier convoys were all on fire and the Germans were jumping into the burning waters. It was all one huge conflagration.’

The prisoners reached Kiel after two days at sea. Three hours after they arrived, British tanks reached the dockside. ‘The English treated us really well,’ the girl from Lodz later recalled. ‘They kissed us and tried to give us new hope and said to us: “Just you wait, luvs. We won’t be a moment and we’ll get us all some food!”’

***

At 11.30 on the morning of Thursday, May 3, just outside the village of Wendisch Even, Grand Admiral Hans Georg von Friedeburg—Dönitz’s successor as Chief of the Naval Staff—and General Hans Kinzel—Chief of Staff to the German North West Army Command—arrived at Field Marshal Montgomery’s headquarters. ‘Who are these men?’ Montgomery asked. ‘What do they want?’

The two German officers had come to surrender three German armies then facing the Russians. Montgomery rejected their offer. Surrender of the forces facing the Russians, he said, must be made to the Russians, and to the Russians alone. They could surrender to him only those armies facing the British; that is, all the German forces in Holland, north-west Germany and Denmark. If they did not agree, Montgomery told them, ‘I shall go on with the war, and will be delighted to do so, and am ready,’ and he went on to warn: ‘All your soldiers will be killed’.

The German officers crossed back through the lines and returned to Flensburg, where they put Montgomery’s conditions to Dönitz. At half past five on the following afternoon they returned; an hour later, they signed the instrument of surrender. In western Austria, the cities of Innsbruck and Salzburg surrendered that day to the Americans, who also entered Hitler’s former mountain retreat of Berchtesgaden, capturing two thousand prisoners.

Also on May 4, the Americans entered Flossenbürg concentration camp. Among those liberated there was the former Prime Minister of France, Léon Blum, whose brother René had been deported to Auschwitz in September 1942, and had perished there. Also liberated that day were the former Chancellor of Austria, Kurt von Schuschnigg, whose challenge to Hitler in March 1938 had exposed the strength of democracy in Austria; and one of the leading figures of German decency, Pastor Martin Niemöller, the former leader of the Confessional Church in Germany who had been held, first in Sachsenhausen then in Dachau, and finally at Flossenbürg, for more than seven years.

Europe from war to peace, May 1945

German armies were still fighting north of Berlin, and in Czechoslovakia; Allied bombing raids against them also continued. On May 4, in one such raid, a bomb killed Field Marshal von Bock, the Commander of German Army Group Centre during the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, whom Hitler had dismissed when the offensive against Moscow was halted. That same May 4, in Zagreb, the ruler of Croatia, Hitler’s former ally, Dr Ante Pavelić, made a final appearance in the streets of his capital. ‘If we must die,’ he declared, ‘let us fall as true heroes, not as cowards crying for mercy’. But then, leaving most of his followers behind him, he hurried northward to the comparative safety of the Austrian border.

***

On May 4, at the United Nations conference which had recently opened in San Francisco, the Soviet Foreign Minister, Vyacheslav Molotov, revealed to a startled American Secretary of State, Edward R. Stettinius, that the sixteen Polish negotiators who had met with the Soviet Colonel Pimenov at Pruszkow near Warsaw on March 27 had ‘been arrested by the Red Army’ on charges of having earlier caused ‘the death of two hundred Red Army officers’. This figure, Eden telegraphed to Churchill from San Francisco, ‘I seem to remember was the same figure Stalin quoted at Yalta’. The effects on American opinion, Eden added, ‘are likely to be serious, and I have no doubt that they will be so at home’.

Churchill replied at once to Eden: ‘The perfidy by which these Poles were enticed into a Russian conference and then held fast in the Russian grip is one which will emerge in great detail from the stories which have reached us, and there is no doubt that the publication in detail of this event upon the authority of the great western Allies, would produce a primary change in the entire structure of world forces’.

At the moment of victory over Germany, the fate of Poland gave Western leaders cause for grave alarm. It was likely, Churchill telegraphed to Truman on May 4, that the territories under Russian control once all the German armies had surrendered ‘would include the Baltic Provinces, all of Germany to the occupational line, all Czechoslovakia, a large part of Austria, the whole of Yugoslavia, Hungary, Roumania, Bulgaria, until Greece in her present tottering condition is reached. It would include all the great capitals of middle Europe including Berlin, Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest and Sofia.’ This, Churchill went on to warn the President, ‘constitutes an event in the history of Europe to which there has been no parallel, and which has not been faced by the Allies in their long and hazardous struggle. The Russian demands on Germany for reparations alone will be such as to enable her to prolong the occupation almost indefinitely, at any rate for many years, during which time Poland will sink with many other States into the vast zone of Russian-controlled Europe, not necessarily economically Sovietised but police-governed’.

Churchill had every intention of trying to forestall what could be prevented of the Soviet military advance. On May 5, he explained to Anthony Eden that, in addition to sending Montgomery to Lübeck to cut off any Soviet advance from the Baltic to Denmark, ‘we are sending in a moderate holding force to Copenhagen by air, and the rest of Denmark is being rapidly occupied from henceforward by our fast-moving armoured columns. I think therefore, having regard to the joyous feeling of the Danes and the abject submission and would-be partisanship of the surrendered Huns, we shall head our Soviet friends off at this point too’.

The Red Army was still in fierce combat on May 5, in northern Germany between Wismar and Schwerin, in East Prussia on the narrow strip of shore between Danzig and Königsberg, in Czechoslovakia near Olomouc, in Austria near St Pölten, and in Silesia, around Breslau. Near Wansen, twenty miles south of Breslau, a monument records the death of 469 Russian soldiers that day, when the German Seventeenth Army launched one last desperate counter-attack.

Several more German surrenders were signed on May 5; one, at Wageningen in The Netherlands, led to the surrender of all German forces in Holland. The surrender was signed shortly after four o’clock in the afternoon, in the presence of a senior Canadian officer, Lieutenant-General Charles Foulkes; also present, in his capacity as Commander-in-Chief of the Netherlands forces of the Interior, was Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands, to whom the commander of the German forces in Holland, General Blaskowitz, showed unexpected deference. The Prince ignored him.

At Baldham, in southern Germany, a further unconditional surrender was signed at half past two in the afternoon of May 5. This time it covered all German forces between the Bohemian mountains and the Upper Inn river. The German officer agreeing to the surrender was General Hermann Foertsch, to whom the American General, Jacob L. Devers, explained that this was not an armistice, but unconditional surrender. ‘Do you understand that?’ Devers asked Foertsch. ‘I can assure you, Sir,’ Foertsch replied, ‘that no power is left at my disposal to prevent it’.

Although the war was virtually over, yet at Ebensee, near Mauthausen, a hundred miles east of Baldham, the SS made plans to kill several thousand Jews, most of them survivors of Auschwitz, who had been marched to Ebensee from Mauthausen. The prisoners were ordered into one of the tunnels of the Ebensee mine. It was, their guards explained, to protect them from Allied bombing.

Among the prisoners at Ebensee was a forty-six-year-old Russian Jew, Lev Manevich, who had been a prisoner in Germany since 1936, when he had been arrested for spying for the Soviet Union. In September 1943 he had been released, briefly, by the Americans, when a small American front line unit had entered the prison of San Stefano, in Italy, but, extremely weak, Manevich had been recaptured by the Germans within forty-eight hours. Now, emaciated, and anonymous, he answered the German order to enter the mine by crying out, in several languages: ‘No one will go. They will kill us.’

Manevich’s warning was effective. To a man, the prisoners refused to move. The SS guards, as the historian of this last revolt, Evelyn le Chêne, has written, ‘were paralysed with indecision. The hordes of humans swayed and murmured. For the first time since their arrest, the prisoners who were not already dying saw the possibility that they might just survive the war. Understandably, they neither wished to be blown up in the tunnel, nor mown down by SS machine guns for refusing. But they knew that in these last days, many of the SS had left and been replaced by ethnic Germans’.

A quick consultation with some of the officers under his command made it clear to the German Commandant ‘that they too were reluctant either to force the men into the tunnel, or to shoot them down. With the war all but over, they were thinking of the future, and the punishment they would receive for the slaughter of so many human beings was something they still wished—even with their already stained hands—to avoid. And so the prisoners won the day.’

Among those at Ebensee that day was Meir Pesker, a Polish Jew from Bielsk Podlaski who had been deported first to Majdanek, then to Plaszow, and finally to Mauthausen. ‘We saw that the Americans were coming,’ he later wrote, ‘and so did the Germans.’ His account continued: ‘Suddenly a German guard appeared, a bloated primeval beast whose cruelty included the bare-handed murder of dozens of Jews. Suddenly he had become weak and emotional and he began to plead with us not to turn him in for he had “done many favours for the Jews to whom that madman Hitler had sought to do evil”. As he finished his pleading three boys overpowered and killed him, there in the same camp where he had been sole ruler’.

Meir Pesker added: ‘We killed every one of the German oppressors who fell into our hands, before the arrival of the Americans in the enclosure of the camp. This was our revenge for our loved ones whose blood had been spilled at the hands of these heathen German beasts. It was only by a stroke of luck—even if tainted luck—that I had survived’.

Also at Ebensee on May 5, as the Germans prepared to flee, was Dr Miklos Nyiszli, an eye-witness of Dr Mengele’s brutality at Auschwitz. Like all his fellow prisoners at Ebensee, he too had survived the death marches, including one from central Germany to Mauthausen on which three thousand had set off, and one thousand been killed on the march. ‘On May 5th,’ he later recalled, ‘a white flag flew from the Ebensee watch-tower. It was finished. They had laid down their arms. The sun was shining brightly when, at nine o’clock, an American light tank, with three soldiers on board, arrived and took possession of the camp. We were free.’

Once again, the moment of freedom was one of deep shock for the liberators. When American troops reached Mauthausen, they found nearly ten thousand bodies in a huge communal grave. Of the 110,000 survivors, 28,000 were Jews. More skeletal bodies, and more emaciated survivors, were found at nearby Ebensee, including Lev Manevich. Like hundreds of those who were liberated, Manevich was too weak to survive; he died four days after his act of defiance.

On May 6, in Berlin, the final awards were made of the much coveted Swords to the Knights Cross of the Iron Cross. The last award of all was made to one of the most highly-decorated and popular of all the SS officers in the fighting units of the SS, Otto Weidinger. It is probable that it was Weidinger’s defence of Vienna that was responsible, at least in part, for this award. But in those final, confused and catastrophic moments of the war, the message announcing the award was lost; indeed, it was only six years later, after his return to Germany following six and a half years of capitivity in France, that Weidinger himself learnt of his award. It had been granted to him three weeks after his forces had been forced to leave Vienna.

The last acts of the European war were about to take place. At six o’clock on the evening of May 6, the commander of the German forces besieged in Breslau, General Nickhoff, accepted the Soviet terms for the surrender of his forces, and of the city. Half an hour later, in the West, General Jodl flew from Flensburg to Reims, to sign the capitulation of all German forces still fighting or facing the Western Allies. At first, Jodl was determined to limit the surrender to the German forces facing westward. But, without prevarication or debate, General Eisenhower made it clear to him that either the Germans agreed to a complete surrender of all their forces, East as well as West, or he would break off all negotiations, and seal the Western Front, thus preventing any more Germans transferring from East to West in order to give themselves up. General Jodl passed back this ultimatum by radio signal to Grand Admiral Dönitz at Flensburg. Shorly after midnight, Dönitz replied, authorizing Jodl to make a final and complete surrender of all German forces on all fronts. At 1.41 on the morning of May 7, watched by General Ivan Susloparov of Russia and by General François Sevez of France, General Jodl signed. General Bedell Smith then signed for the Allied Expeditionary Force and General Susloparov for the Soviet High Command. Finally, General Sevez signed as a witness. The surrender was to come into effect at fifty-nine minutes to midnight on May 8. The war in Europe still had twenty-one hours and eighteen minutes to run.

In Czechoslovakia, throughout May 7, German forces continued to fight the Red Army north of Olomouc and in the town itself. On the long spit of land between Danzig and Königsberg, German troops continued to fight the Russians near the village of Vogelsang. Just off the coast of Scotland, in the Firth of Forth, one mile south of the Isle of May, the German submarine U-2336, commanded by Captain Emil Klusmeier, sank two merchant ships, the Norwegian Sneland 1 and the British Avondale Park. On the Sneland 1, seven Norwegian merchant seamen were killed; two British seamen died on the Avondale Park. These nine merchant seamen were the last Allied naval deaths of the European war.

In five years and eight months of submarine war, 27,491 officers and men on German submarines had been killed. Of the 863 U-boats that had gone on operational patrols, 754 had been sunk, or damaged beyond repair while in port. Their success had been considerable, however, with 2,800 Allied merchant ships and 148 Allied warships being sunk. Their own end was ignominious; under Operation Rainbow, launched in that first week of May, 231 U-boats scuttled themselves, rather than fall into Allied hands. Among those scuttled were many which had never put to sea, including, at Lübeck, several which were to have been powered by the new hydrogen-peroxide method. One of their inventors, Helmuth Walter, captured by the British on May 5, agreed two days later to give the Allies details of all new submarines and torpedoes then under construction at the nearby research stations at Eckernförde. One of the new type of submarines was shipped to America for trials, another to Britain.

***

In Prague, Czechoslovak resistance forces had taken up arms against the German forces in the city on May 7; that day, three American Army vehicles arrived. But so did the Russians, who insisted that, under Eisenhower’s agreement with the Soviet High Command, the Americans withdraw to Pilsen. The Americans complied.

Throughout May 7, the fighting in Prague continued. Then, at four minutes past five on the morning of May 8, the German forces in the city surrendered unconditionally. In the battle for Prague, more than eight thousand Soviet soldiers, and considerably more German soldiers, had been killed, the last substantial blood-letting of the German war.

***

In Britain and the United States, May 8 was VE-Day—Victory in Europe Day. As both nations rejoiced, their cities were bedecked with flags and banners. In the once captive capitals of Western Europe—The Hague, Brussels and Paris—there was a renewal of the excitement and relief of their days of liberation. In Copenhagen and Oslo, the Germans laid down their arms. That same day, the last of the German forces in eastern Germany signed an instrument of surrender to the Russians at Karlshorst, near Berlin. That day, the German troops cut off for many months in northern Latvia likewise surrendered, as did those in the Dresden—Görlitz area. Only around Olomouc did the Germans fight on, but it was a brief and hopeless resistance; Olomouc fell during the day, as did Sternbeck, further north.

At two in the afternoon of May 8, the German garrison at St Nazaire, on the Atlantic surrendered to the Americans. An hour later, the Dame of the small Channel Island of Sark raised both the British Union Jack and the United States Stars and Stripes over her tower. There were still 275 Germans on the island, and not a single Allied soldier. The British Army, three officers and twenty men, arrived two days later.

In Berlin, half an hour before midnight on May 8, a further signing took place of the Reims surrender; the signatories for the German High Command being Grand Admiral von Friedeburg, signing his third instrument of surrender in four days; General Hans-Jurgen Stümpff, Head of the German Air Force, and Field Marshal Keitel. Four Allied witnesses added their names to the surrender document: Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder for the Allied Expeditionary Force, Marshal Zhukov for the Supreme High Command of the Red Army, General de Lattre de Tassigny, General Commanding-in-Chief of the First French Army; and General Carl Spaatz, commanding the United States Air Forces.

Even as the Berlin surrender ceremony was in progress, the German forces in western Czechoslovakia were in receipt of a call by Marshal Koniev, issued at eight o’clock that evening, that they too surrender. When, by eleven o’clock, they had made no reply, Koniev ordered his artillery to launch a new barrage, and his troops to resume military operations. As they did so, the German guards in charge of one of those many groups of Jews who were still being shunted by rail through the Sudeten Mountains, towards Theresienstadt, suddenly fled. ‘We can’t believe it’s over!’ Alfred Kantor, one of the deportees, recalled of that moment at eleven o’clock on the night of May 8 when they were no longer being guarded. Of the thousand men who had begun that particular terrible rail journey less than two weeks earlier, only 175 were still alive. ‘Red Cross trucks appear,’ Kantor wrote, ‘but can’t take 175 men. We spend the night on the road—but in a dream. It’s over.’