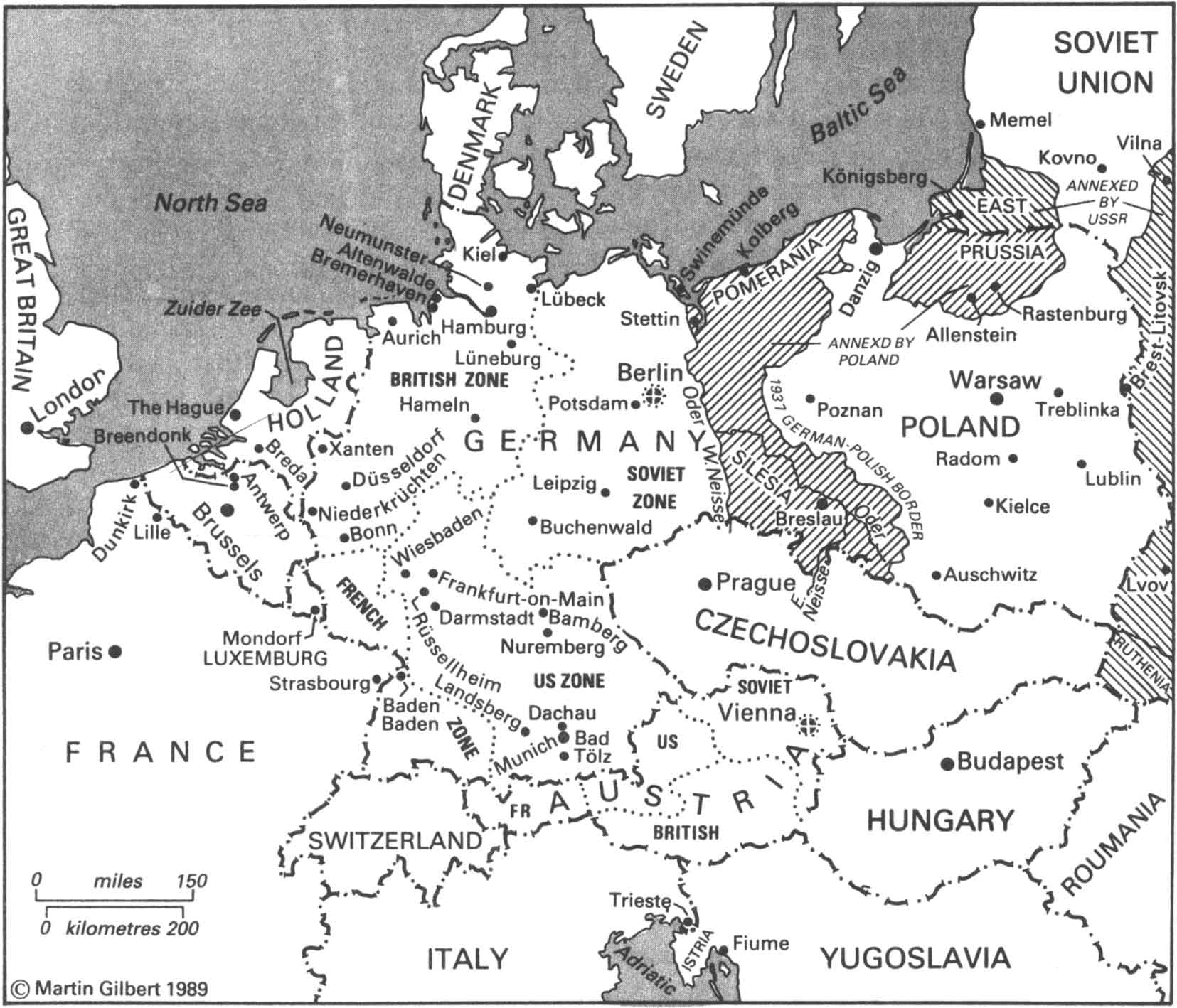

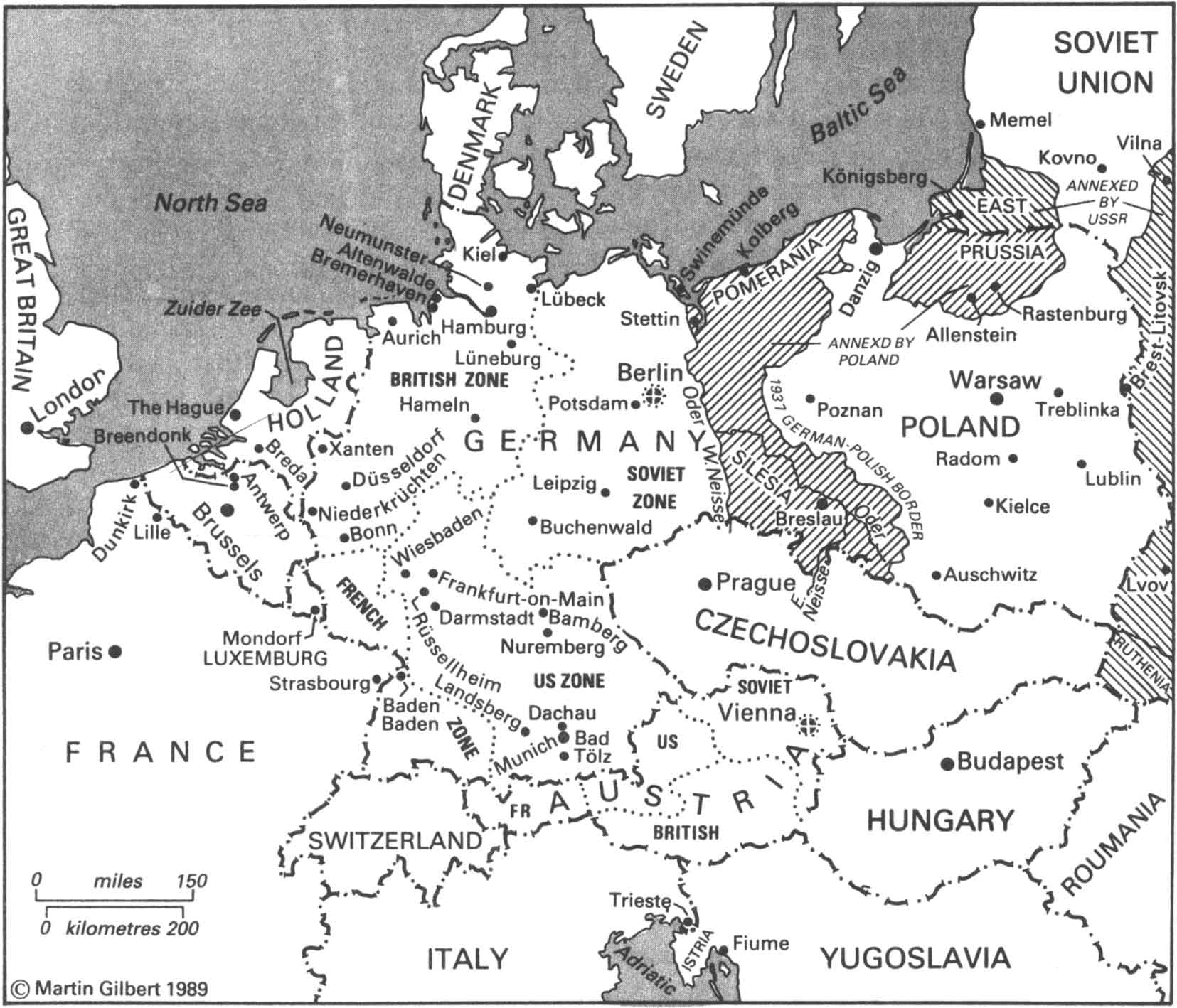

Post-war Europe

At half past five in the morning of 16 July 1945, the first atomic bomb was successfully tested at Alamogordo, New Mexico, in the United States. ‘The sun can’t hold a candle to it!’ was the reaction of one of the physicists as he watched the light of the explosion dazzle with its reflection on the surrounding hills. At Ground Zero, the temperature at the moment of explosion had been three times hotter than the interior of the sun, and ten thousand times the heat of the sun on its surface. As had never happened before, the steel scaffold on which the experimental bomb had stood had been transformed into gas by the intense heat, and had dispersed. Within a mile radius of the explosion, all plant and animal life had vanished.

It was immediately clear that something quite extraordinary had happened. As far away as two hundred miles, windows had been blown out. A hundred and fifty miles away, bewildered citizens reported that the sun had come up and then gone down again. Many of the measuring devices and instruments set up in the desert had been swept away. Most of the film in the scientists’ cameras had been completely fogged—by radiation. That same day, in Berlin, the Allied leaders were gathering for their final conference on the future of the defeated Germany; that day, Churchill was given a guided tour through the ruins of Hitler’s Chancellery.

The Big Three conference opened at Potsdam on July 17, to discuss the continuing war against Japan, and the post-war settlement in Europe. As the conference began, Allied bombers, taking off from American and British ships, attacked military installations and airfields around Tokyo, while other American bombers hit at the industrial towns of Mito and Hitachi, on Honshu Island. But it was the news of the successful testing of the atomic bomb which led to the most dramatic information sent to Potsdam that day. ‘Operated on this morning,’ a top-secret telegram informed the American Secretary for War, Henry Stimson, and it continued: ‘Diagnosis not yet complete, but results seem satisfactory and already exceed expectations.’

It was also necessary, Stimson was told, for a local press release to be issued, ‘as interest extends great distance’. The local press release stated that an ammunition dump had exploded, ‘producing a brilliant flash and blast’, which had been observed more than two hundred miles away.

At noon that day, Stimson, at lunch with Churchill, handed him a sheet of paper on which was written: ‘Babies satisfactorily born.’ Churchill had no idea what the message meant. ‘It means’, Stimson explained, ‘that the experiment in the Mexican desert has come off. The atomic bomb is a reality.’

Later that day, Churchill and Stalin held a private conversation, during which Stalin told the British Prime Minister that, when he was leaving Moscow for Berlin, a message had been delivered to him through the Japanese Ambassador. ‘It was from the Emperor of Japan,’ Stalin explained, who had ‘—stated that “unconditional surrender” could not be accepted by Japan but that, if it was not insisted upon, “Japan might be prepared to compromise with regard to other terms”.’ According to the message, Stalin added, ‘the Emperor was making this suggestion “in the interests of all people concerned”.’

Churchill pointed out to Stalin that, while Britain shared America’s aim ‘of achieving complete victory over Japan’, at the same time people in America ‘were beginning to doubt the need for “unconditional surrender”. They were saying: was it worth while having the pleasure of killing ten million Japanese at the cost of one million Americans and British?’

The Japanese realized the Allied strength, Stalin commented, and as a result they were ‘very frightened’. They could see what unconditional surrender meant in practice ‘here in Berlin and the rest of Germany’.

On the battlefront, the Japanese were now trying to limit their commitments. But on July 20, as Japanese troops tried to escape from Burma through Moulmein, British bombers flew 3,045 sorties against them in nine days, when more than ten thousand Japanese were killed. Since the British had started on the reconquest of Burma a year earlier, more than 100,000 Japanese soldiers had lost their lives in action; thousands more had died of disease and privation in the hostile jungle.

***

In Berlin, on July 21, during a short break in the Potsdam Conference, Churchill took the salute of the British forces in the city. That morning’s parade, he told them, ‘brings back to my mind a great many moving incidents in these last, long, fierce years. Now, here in Berlin, I find you all established in this great centre, from which, as from a volcano, fire and smoke and poison fumes have erupted all over Europe twice in a generation. And in bygone times also German fury has been let loose on her neighbours, and now it is we who have our place in the occupation of this country’.

At Potsdam, considerable areas of disagreement had opened up among the former Allies. During the discussions of the Big Three on the afternoon of July 21, Churchill told Stalin that the situation in Vienna and Austria was ‘unsatisfactory’; Britain had not been allowed even now to take up her zone in Vienna or in Austria, although three or four months had passed since discussions started. In reply, Stalin informed the Conference that he had agreed ‘the previous day’ to the recommendations of the European Advisory Commission, so that the way was ‘now free’ to fix the date for the entry of the British and American troops into their zones; ‘so far as he was concerned this could start at once’.

Post-war Europe

The discussion then turned to Poland. In a memorandum submitted to the Conference, the Soviet delegation had argued that Poland’s western frontier should run to the west of Swinemünde, as far as the River Oder, leaving the city of Stettin on the Polish side, then up the River Oder to the confluence with the Western Neisse, and from there along its course to the northern border of Czechoslovakia.

It was Truman who protested that this movement of the Polish frontier so far westward was the equivalent of giving Poland a zone of occupation of her own in Germany. But the agreement to divide Germany into four zones of occupation, British, American, French and Soviet, was based upon the 1937 frontiers. The frontier now proposed for Poland was well inside this area.

He wished it to be ‘clearly understood’, declared Truman, ‘that Germany should be occupied in accordance with the zones stated at Yalta’. But Stalin replied that the Germans had fled from the eastern regions which Poland now intended to occupy.

***

On July 22, at Potsdam, Henry Stimson brought Churchill a detailed account of the effect of the atomic bomb test at Alamogordo. Inside a one-mile circle, Stimson reported, the devastation had been absolute. Churchill went at once to see Truman. ‘Up to this moment,’ Churchill later recalled, ‘we had shaped our ideas towards an assault upon the homeland of Japan by terrific air bombing and by the invasion of very large armies’. Churchill added: ‘We had contemplated the desperate resistance of the Japanese fighting to the death with Samurai devotion, not only in pitched battles, but in every cave and dug-out. I had in my mind the spectacle of Okinawa Island, where many thousands of Japanese, rather than surrender, had drawn up in line and destroyed themselves by hand-grenades after their leaders had solemnly performed the rite of hara-kiri. To quell the Japanese resistance man by man and conquer the country yard by yard might well require the loss of a million American lives and half that number of British—or more if we could get them there: for we were resolved to share the agony’.

Now, Churchill recalled ‘all this nightmare picture had vanished. In its place was the vision—fair and bright indeed it seemed—of the end of the whole war in one or two violent shocks. I thought immediately myself of how the Japanese people, whose courage I had always admired, might find in the apparition of this almost supernatural weapon an excuse which would save their honour and release them from their obligation of being killed to the last fighting man’.

On July 24, while still at Potsdam, Churchill, Truman, and the representatives of China agreed to send a message to Japan, offering her ‘an opportunity to end the war’. What had happened in Germany, the message read, ‘stands forth in awful clarity as an example to the people of Japan’. The ‘full application’ of Allied military power, ‘backed by our resolve, will mean the inevitable and complete destruction of the Japanese forces, and just as inevitably the utter devastation of the Japanese homeland’. It was now for Japan to decide ‘whether she will continue to be controlled’ by those who had brought her ‘to the threshold of annihilation’, or whether she would follow ‘the path of reason’.

The Big Three then set out their ‘terms’, adding that there were no alternatives, and that ‘We shall brook no delay.’ The influence and authority of those who had ‘deceived and misled’ the people of Japan would have to be ‘eliminated for all time’. The Japanese forces would have to be ‘completely disarmed’. Japanese sovereignty would be limited to the four main islands of Japan ‘and such minor islands as we determine’. Freedom of speech, of religion and of thought, ‘as well as respect for fundamental human rights’, would be established. In return, Japan would be allowed to maintain ‘such industries as will sustain her economy’ and would be permitted ‘eventual participation in world trade relations’. The message ended: ‘We call upon the Government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all the Japanese armed forces, and to provide proper and adequate assurances of their good faith in such action. The alternative for Japan is complete and utter destruction.’

The Japanese had failed to involve the Russians as peace-makers. They had also failed to undermine the Russian pledge, made five months earlier at Yalta, to enter the war against Japan within two to three months of the end of the war in Europe.

Hardly had this call for unconditional surrender been agreed to between America, Britain and China, than Truman approached Stalin, to tell him privately that the United States had just tested a bomb of extraordinary power. During that same day, Truman also discussed with Stimson when this new bomb was to be dropped, and on what sort of target. ‘The weapon is to be used against Japan between now and August 10th,’ Truman wrote in his diary on July 24, and he added that he had instructed Stimson ‘to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children. Even if the Japs are savages, ruthless, merciless and fanatic, we as the leader of the world for the common welfare cannot drop this terrible bomb on the old capital or the new’.

Truman went on to confide to his diary that he and Stimson were ‘in accord’ about the use of the atomic bomb on a military target, and he explained that: ‘The target will be a purely military one and we will issue a warning statement asking the Japs to surrender and save lives. I’m sure they will not do that, but we will have given them the chance. It is certainly a good thing for the world that Hitler’s crowd or Stalin’s did not discover this atomic bomb. It seems to be the most terrible thing ever discovered, but it can be made the most useful’.

On July 24, as these decisions were made at Potsdam, American carrier-based bombers attacked the Kure naval base on mainland Japan, as well as Japanese airfields at Nagoya, Osaka and Mito. They repeated their attack on the following day, when twenty-two British warships, including two carriers and their aircraft, launched Operation Cockpit against Japanese port and oil installations on Sabang Island, off the northern tip of Sumatra. Considerable damage was caused. Also on July 25, the Americans announced that all organized Japanese resistance had ceased on the Philippine island of Mindanao.

***

On July 25, a war crimes trial began at Darmstadt, in the American zone of Germany. The eleven accused, nine men and two women, were those who, in Rüsselheim in August 1944, were believed to have participated in the killing of six American airmen, who had earlier been shot down and were on their way to a prisoner-of-war camp. Seven of the accused were found guilty, including the two women. The five men were hanged, the sentences being carried out by the United States military executioner, Master-Sergeant John C. Wood.

While the Darmstadt trial was in its second day, the British Government set up a Missing Research and Enquiry Service, to try to locate the 42,000 British airmen who had not returned from air missions over wartime Europe, but whose fate was still unknown.

***

On July 26, at seven in the evening, President Truman’s staff issued the Potsdam Declaration on Japan to the newspapers. That same day, in the Pacific, the American cruiser Indianapolis arrived at Tinian Island with the atomic bomb on board. Waiting for it were the scientists who would assemble it and the aircrew who would drop it. Even the aircraft which would carry the bomb to Japan had been chosen and made ready; she was the ‘Enola Gay’.

At a specially called press conference on the afternoon on July 26, the Japanese Prime Minister, Admiral Kantaro Suzuki, rejected the Potsdam Declaration. ‘As for the Government,’ he said, ‘it does not find any important value in it, and there is no other recourse but to ignore it entirely and fight resolutely for the successful conclusion of the war.’

On July 28, American carrier-based aircraft struck again at the Japanese naval base at Kure. Five Japanese warships were sunk, including the aircraft carrier Amagi and the heavy cruiser Tone; of the twenty-five Japanese warships involved in the attack on Pearl Harbour, the Tone was the twenty-fourth to be sunk. Only one, the destroyer Ushio, was to survive the war.

Air and sea bombardment of the Japanese home islands was now an almost daily event. On July 29, an American naval squadron shelled an aircraft factory at Hamamatsu, on Honshu Island. That same day, however, disaster struck for the American cruiser Indianapolis, torpedoed just before midnight between Tinian and Guam, while she was on her way, unescorted, first to Guam and then to Okinawa, to train for the still-projected invasion of Japan on November 1. Amid fire and darkness, more than 350 of her crew of 1,196 were killed in the explosion or went down with the ship. More than eight hundred were pitched or slid into the sea. Fifty of them, mostly those who had been injured during the submarine attack, died during the night. On the following morning, sharks attacked the survivors. There were no ships near to rescue the desperate men, nor had there been time for any distress call; the sun blinded them; sea water, which many drank in their desperation, drove them mad. Not until the morning of August 2 were those who still survived spotted from the air. Until then, the ship had not even been missed. Now, after the men had been eighty-four hours in the water, a rescue operation began. Only 318 sailors were still alive; 484 had died in the water, either eaten by sharks or drowning in the ocean.

In all, 883 men had died in the Indianapolis disaster, the greatest loss at sea in the history of the United States Navy, and the last major warship to be lost at sea in the Second World War. For the Japanese, it was a welcome success in a losing struggle. The officer who had been in charge of the Japanese submarine, Lieutenant-Commander Mochitsura Hashimoto, a veteran of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, later recalled how, on the day after the sinking of the Indianapolis, ‘we celebrated our haul of the previous day with our favourite rice with beans, boiled eels, and corned beef (all of it tinned)’.

Commander Hashimoto also sent a radio message to Tokyo, stating that he had sunk ‘a battleship of Idaho class’, and giving the exact latitude and longitude. Although no radio message reached the Americans from the stricken Indianapolis, Commander Hashimoto’s victorious signal was intercepted as a matter of routine by American Signals Intelligence, and decoded. By the morning of July 30, a copy of the decoded message had been sent to American naval headquarters on Guam. The Seventh Fleet also received a copy. But, as Japanese claims of sinkings were almost always absurdly exaggerated, no one thought to ascertain what ship it might be, or to check the area by air search. Had that been done, rescue efforts might have been started a full three days before they were in fact begun.

***

On July 30, in connection with the plans for the dropping of the atomic bomb on the four target cities earlier agreed, General Carl Spaatz telegraphed to Washington that Hiroshima, ‘according to prisoner-of-war reports’, was the only one of the four ‘that does not have Allied prisoner-of-war camps’. He was told, by return of signal, that it was too late now to change the targets, ‘however, if you consider your information reliable, Hiroshima should be given first priority among them.’

The Japanese had continued to work for Soviet mediation, hoping to circumvent the Anglo—American—Chinese call for unconditional surrender by the opening up of negotiations for a compromise peace. On August 2, an American Intelligence analysis based on the Magic intercepts noted that Japan was ‘still balking at the term unconditional surrender’, and also ‘still determined to exploit fully the possible advantage of making peace first with Russia’. After reading the Magic intercepts on which these conclusions were based, Secretary of the Navy, James R. Forrestal, commented that the Japanese Cabinet seemed to have decided ‘that the war must be fought with all the vigour and bitterness of which the nation is capable, so long as the only alternative is unconditional surrender’.

***

In the early hours of July 31, two British midget submarines, having been towed by submarine from the Philippines, entered Singapore dockyard. Emerging from one of the submarines only with difficulty, and then working underwater for half an hour, amid great risk, Leading Seaman Mick Magennis, an Irishman from Belfast, scraped the seaweed and barnacles from the hull of the Japanese cruiser Takao, in order to fix six limpet mines to its hull. For his exceptional courage, both he and the midget submarine’s captain, Lieutenant Ian Fraser, were awarded the Victoria Cross.

A large hole was blown in the hull of the Takao, but, being in shallow water, she settled on the sea bed. No doubt had she been in deep water she would have sunk. Somewhat to the chagrin of the British submariners, it was later learned that an American submarine had already damaged the cruiser’s stern at sea.

***

On August 2, the Potsdam Conference came to an end. Among the agreements which it reached was ‘the removal of Germans from Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary’. Many of these Germans were already on the move. The Conference also transferred all of eastern Germany between the 1937 border and the Oder—Neisse line to Poland. Churchill had been uneasy at the Russian insistence upon the Western and not the Eastern Neisse; but in mid-conference he had returned to London to learn the British General Election results, in which his Conservative Party had been defeated. It was the new Labour Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, who had returned to Potsdam to conduct the final negotiations.

As well as Poland’s gain of Pomerania and Silesia from Germany, she also divided the German province of East Prussia between herself and the Soviet Union. Hitler’s ‘Wolf’s Lair’ at Rastenburg was now on Polish soil. Under Soviet sovereignty fell the eastern regions of pre-war Poland, including the once predominantly Polish cities of Vilna and Lvov. Just as several million Germans moved westward from the new Poland to Germany, so millions of Poles now moved westward from the new Russia to Poland; many of these Poles were to be settled on land taken from Germany, and Germany’s eastern cities acquired new names. Stettin became Szczecin; Breslau, Wroclaw; Kolberg, Kolobrzeg; Allenstein, Olsztyn; and Rastenburg, Ketrzyn.

At the end of the First World War, when, instead of unconditional surrender, the Germans and their allies had been allowed to accept an armistice, the terms of peace had been negotiated. During the course of these negotiations, the victors had nevertheless effectively imposed their wishes on the defeated States. Territory was taken away, reparations were secured, and armies disbanded in the guise of a negotiated peace. This peace had soon been denounced as a ‘dictated’ one, and political agitators, among them Hitler, had stirred up intense nationalism through these denunciations. The Allies were determined not to allow that situation to recur; hence their insistence on unconditional surrender. The boundaries and the conditions to be created in the post-war world would be subject neither to negotiation nor discussion with those who had been defeated. By this method, the Allies intended that Potsdam would not repeat what had been seen as the errors and weaknesses of Versailles. The Germans would not be able to feel that their leaders had let them down at the negotiating table; the negotiations at Potsdam had been conducted without any German representation.

***

President Truman, returning home to the United States, lunched with King George VI at Plymouth, on board the battleship Renown. Much of the conversation revolved around the atomic bomb. One member of Truman’s party, Admiral Leahy, was sceptical of the effect the bomb would have. ‘It sounds like a professor’s dream to me’ was his comment, whereupon the King remarked: ‘Would you like to lay a little bet on that, Admiral?’

The Japanese had become concerned lest Russia, unwilling to negotiate with them, were to join in the attack against them. But on August 4, the operations section of the 700,000 strong Japanese Army in Manchuria concluded that no Soviet attack was possible until September, nor was such an attack probable, the section believed, until the spring of 1946.

That August 4, at a naval base in Singapore, the Japanese executed seven captured American airmen. One of the Japanese cooks at the base, Oka Harumitzu, later recalled that, previously, fourteen or fifteen other prisoners-of-war had been similarly executed.

***

In preparation for an American amphibious landing on Kyushu, the Japanese had trained considerable numbers of kamikaze suicide pilots, kaiten suicide human torpedoes and fukuryu suicide divers. By August 1945, as many as 1,200 suicide divers had been trained, with a further 2,800 under training. Their task would be to position themselves off shore, in underwater concrete shelters with iron hatches, ready to emerge as the landing craft arrived, and to fix their mines on the hulls. The landing craft, their men and tanks, and the diver, would then all be blown up together.

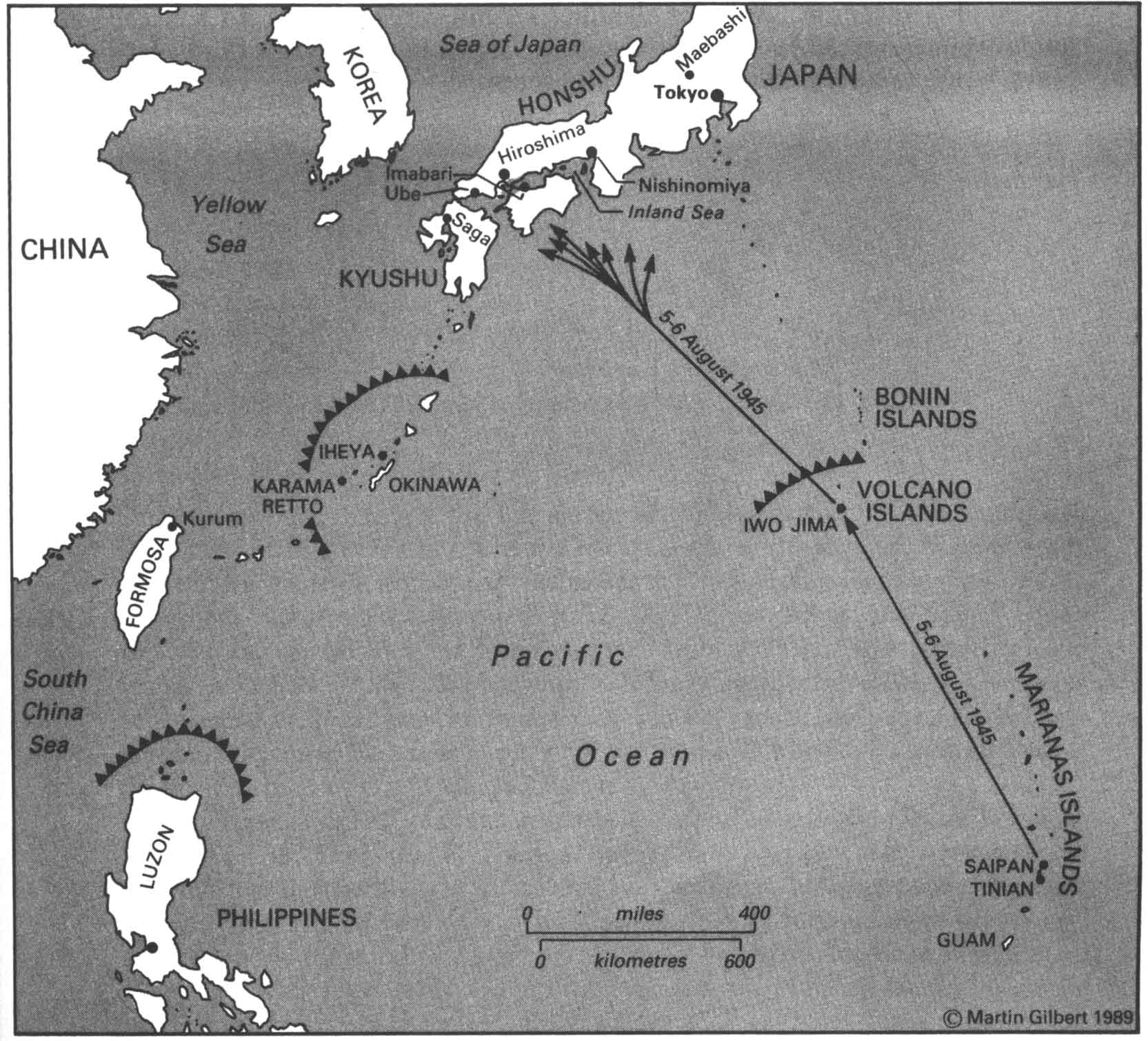

On the night of August 5, seven groups of American bombers set off to bomb mainland Japan. Thirty of the bombers flew through the night to drop mines on the Inland Sea; sixty-five were on their way to bomb Saga; 102 were on an incendiary raid on Maebashi; 261 were to strike at the Nishinomiya—Mikage area; 111 were on their way to Ube; sixty-six were flying against Imabari; and one was flying, with two back-up planes, to Hiroshima.

This seventh mission was Operation Centreboard. It began at a quarter to three in the early hours of August 6, when the B-29 bomber, the ‘Enola Gay’, which had been especially adapted to carry an atomic bomb, took off from Tinian Island in the Marianas. Five and a half hours later, at a quarter-past eight in the morning Japanese time, it dropped its atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Among the messages scrawled on the bomb was one which read: ‘Greetings to the Emperor from the men of the Indianapolis.’

Captain Robert A. Lewis, the aircraft commander on the ‘Enola Gay’, saw the massive, blinding flash of the explosion, his fellow crewmen heard him call out: ‘My God, look at that son-of-a-bitch go!’ In that instant, 80,000 people were killed, and more than 35,000 injured.

Of the 90,000 buildings in Hiroshima when the bomb fell, 62,000 were destroyed. Of the two hundred doctors in the city, 180 were killed or badly injured. Of the city’s fifty-five hospitals and first aid centres, only three could still be used. Of the city’s 1,780 nurses, less than 150 could attend to the sick. Several American prisoners-of-war being held in Hiroshima castle since they had been shot down over the city eight days earlier were also killed. The city burned: ‘I am starting to count the fires,’ Staff Sergeant Caron recorded as he looked back. ‘One, two, three, four, five, six… fourteen, fifteen… it’s impossible. There are too many to count.’

‘It’s pretty terrific,’ another of the crewmen, Jacob Beser, commented, and he added: ‘What a relief it worked.’

***

The scale and nature of the destruction of human life at Hiroshima was eventually to alter the whole nature of how mankind looked at wars, power, diplomacy and the relationships between states. In the days when its reality was only slowly becoming apparent, it was the terrifying human aspects which each survivor could not shake out of his or her nightmares. ‘Mother was completely bedridden,’ a nine-year-old boy later recalled of the days following the bomb. ‘The hair of her head had almost all fallen out, her chest was festering, and from the two-inch hole in her back a lot of maggots were crawling in and out. The place was full of flies and mosquitoes and fleas, and an awfully bad smell hung over everything. Everywhere I looked there were many people like this who couldn’t move. From the evening when we arrived mother’s condition got worse and we seemed to see her weakening before our eyes. Because all night long she was having trouble breathing, we did everything we could to relieve her. The next morning grandmother and I fixed some gruel. As we took it to mother, she breathed her last breath. When we thought she had stopped breathing altogether, she took one deep breath and did not breathe any more after that’.

The seven bombing missions of 5–6 August 1945

That was thirteen days after the bomb had exploded over Hiroshima; by then, the death toll had risen by a further twelve thousand, reaching 92,233. It was to rise still further in the following years from the illnesses resulting from radiation. In 1986, the number of identified victims was given on the Cenotaph in Hiroshima as 138,890. People were still dying from the effects of radiation, nearly half a century after the bomb was dropped.