13

Social scientists use many different types of research tools to study behavioral and sociocultural phenomena. These include questionnaires and direct observations, which are analyzed using a variety of statistical tools. Underlying these measurement and statistical procedures are conceptual tools, known as theories, models, and hypotheses. In this chapter, we explore the nature of these conceptual tools and the important roles they play in helping scientists to make sense of their research efforts.

Conducting scientific research can be an end in itself, but often scientists would like to be able to integrate what they learn from a particular study into a broader fabric of knowledge. Achieving such an integration can lead to insights at an entirely different level than the understanding that comes simply from the results of a single study. The integration of knowledge from dozens, and sometimes even hundreds, of individual studies, and then using such knowledge to predict things that remain to be investigated involves mentally constructing theories, which are among the most prized achievements in science (Schofield & Coleman, 1986, 1). This chapter discusses how theories (and related concepts) help to consolidate and guide scientific research.

THE CONCEPT OF CAUSATION

As this chapter reveals, causation is central to scientific theorizing. The concept of causation is difficult to precisely define, in part, because it covers a wide range of phenomena. Nevertheless, if we say that Variable A is a cause of Variable B, we mean that Variable A precedes Variable B time-wise and that Variable A is nearly always present wherever Variable B is present. Complicating this picture is the fact that most variables are not simply present or absent, but present to widely varying degrees (recall the handedness example from chapter 6). Furthermore, effects often result from not just one causal variable, but from two or more variables that are interacting.

About the only thing that is true of all causal variables is that they must occur prior to an event to have their effect. In other words, the way the universe is conceptualized means that it is impossible for an effect to precede a cause, with the following qualification. According to the reinforcement principles of learning, a particular type of behavior can be made more probable by making rewards contingent upon the behavior (Skinner, 1953). For instance, the probability that a rat will press a lever in the future can be increased by rewarding earlier instances of the lever-pressing (usually with food). While it is true that this particular type of behavior (e.g., lever pressing) is being altered by events following the behavior, each individual incidence of the behavior is not being caused by its consequences. Instead, the behavior is being altered by the anticipation of those consequences, based on past experience.

Obviously, the concept of causation is fraught with complexities, but there is no way to overemphasize the importance of this concept in science. At the heart of most scientific theories are proposals about how variables are connected in causal sequences.

THE NATURE OF SCIENTIFIC THEORIZING

As the word is used in ordinary language, theory often denotes something that is the complete opposite of ‘‘fact’’ or ‘‘truth’’ (Maris, 1970, 1070). Statements such as ‘‘Oh, that’s just a theory’’ imply that theories and ‘‘truth’’ have little in common. As this chapter shows, however, theories and empirical reality can be interrelated in ways that make possible many of the great leaps in science.

To begin this exploration of the role of theories in social science research, consider the following question: If a theory is not a fact (which it is not), why do scientists take the time to propose theories? To answer this question, a few basic definitions are needed. A theory is a set of logically related statements from which a number of hypotheses may be derived (Taylor & Frideres, 1972, 465). A hypothesis is a statement about empirical reality that may or may not be true. Unfortunately, the words theory and hypothesis are sometimes used interchangeably (Laughlin, 1991, 148; McBroom, 1980, 181), a practice that has been justifi-ably criticized (Birdsell, 1987, 8). For example, the statement ‘‘drinking alcohol is dangerous to one’s health’’ should be considered a hypothesis, not a theory (Kraemer & Thiemann, 1987, 22). A theory would offer an explanation for why such a hypothesis might or might not be true, and would lead to additional testable hypotheses.

Levels of Abstraction

Theories can also be thought of in terms of their levels of abstraction (Short, 1997, 37). A theory as to why a particular war occurred would be at a much lower level of abstraction than a theory intended to explain all wars. Similarly, a theory that explained variations in personality and in mental health, as well as in social stratification would be at a higher level of abstraction than one that explained just one or two of these phenomena.

Scientists are continually striving to understand empirical reality at higher and higher levels of abstraction. This means that someday, a scientist may propose a theory of everything! Were such a grandiose theory to be espoused, it should lead to testable hypotheses regarding everything from the origins of the universe to subtle features of human behavior. Given the complexity of both living and non-living matter, it is reasonable to expect no such ‘‘ultimate theory’’ in the near future.

What is Truth?

In science, the concept of truth is slippery. As a result, many scientists avoid using the term except in casual discourse. To the degree truth has meaning in science, it applies to hypotheses, not to theories. This is because by definition, a theory cannot be directly tested. A theory’s truth can only be inferred if it is found to lead to ‘‘true hypotheses.’’

To illustrate this point, suppose that some theory were to lead one to hypothesize that Variable A and Variable B should be negatively related. Further assume that ten massive studies were undertaken throughout the world and all found essentially the same –.60 correlation between these two variables. One would obviously have a very strong basis for concluding that the hypothesis was true. Nevertheless, a careful scientist would still not declare the hypothesis of Variables A and B being negatively correlated to be true. Instead, he or she would (and should) state something to the effect that ‘‘a great deal of evidence supports such a hypothesis.’’ Why so much caution? Because scientists have not yet seen the findings from an eleventh study, and a prudent scientist is always open to future contrary (or at least qualifying) evidence. Once a person states that ‘‘such-and-such is true,’’ in principle, he or she is no longer open to additional evidence unless it supports his or her conclusion.

Now assume that a researcher is aware of a theory that predicts that Variables A and B will be negatively correlated. Can this researcher justifiably declare the theory to be true? There are three reasons for answering no. One is that, as explained previously, even though ten studies have all confirmed the relationship, the next study to be conducted might not do so. Second, a ‘‘good’’ theory leads to numerous hypotheses, not just one or two, all of which need to be tested. Third, other theories may lead to the same hypothesis.

CRITERIA FOR ASSESSING THE ELEGANCE OF A SCIENTIFIC THEORY

Since the concept of ‘‘truth’’ cannot be applied to theories (although it may be applied in casual scientific discussions), ‘‘good’’ theories are said to have merit, or to be elegant. The elegance (or merit) of a theory can be judged on the basis of six criteria. These criteria are presented roughly in the order of importance.

Predictive Accuracy

The most important basis for assessing the elegance of a theory involves how accurately it predicts what researchers observe. If a theory does a poor job of predicting empirical reality, it is said to have little merit. In general, the assessment of a theory’s predictive accuracy comes slowly. This is true partly because few scientists may be interested in testing a new theory, and partly because observations may be difficult to make. Also, if erroneous results are obtained by any of the early studies (due to invalid measurements of one of the key variables, for example), the theory may be assumed to lack merit, thus discouraging other researchers from bothering to test hypotheses derived from it.

Technically speaking, theories can make two types of predictions: retrodictions and true predictions. Retrodictions are predictions that can be derived from a theory that has already been documented. For example, research has repeatedly documented throughout the world that males are more involved in serious persistent criminality than females (Ellis et al., 2009, 11–17). If a theory were now to be proposed that ‘‘predicts’’ that male involvement in serious persistent offending would surpass female offending in all societies, the theory would be considered elegant in this respect. Contrariwise, any theory that explicitly ‘‘predicts’’ that in some societies females would be more involved in serious persistent offending than males would lack elegance regarding this particular hypothesis. The key point to note is that what is being ‘‘predicted’’ has actually already been documented.

In the case of true predictions, a theory leads to a hypothesis that has not yet been investigated, or, if investigated, the evidence is still unsettled. Confirmation of a true prediction is considered more impressive than confirmation of a retro-diction in terms of assessing the elegance of a scientific theory (Blaug, 1980, 262). In other words, suppose that some newly published theory predicts that Variables A and B will be positively correlated, but that no study has yet investigated such a possibility. Further suppose that three or four studies are conducted in subsequent years, and the prediction is confirmed in all cases. This would be considered more of a testament of the theory’s elegance than if the research findings already existed in the scientific literature prior to publication of the theory.

Predictive Scope

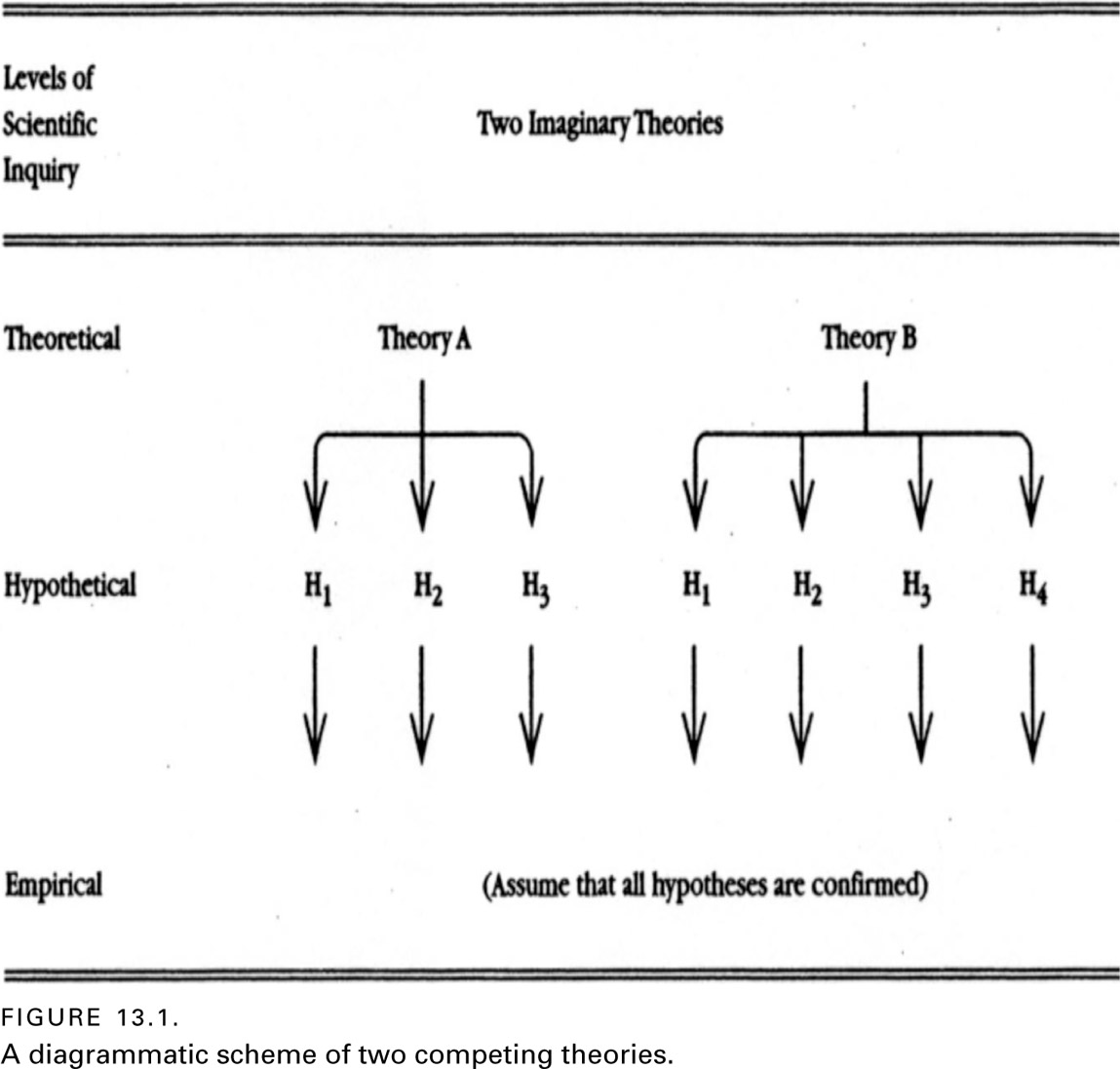

Predictive scope refers to the number of hypotheses that can be accurately predicted by a theory. Thus, if two competing theories accurately predict the same number of hypotheses, their predictive scope is equivalent. This concept of predictive scope is illustrated in figure 13.1. To conceptualize this diagram, one may recognize three levels at which scientists inquire about some phenomenon in which they have an interest. The basic level consists of the empirical observations made with little idea of what one will find. Directly ‘‘above’’ the level of empirical observations are the expectations (or hypotheses) that scientists have about what will be found when the observations are compiled and analyzed. Finally, ‘‘overseeing’’ these expectations is a level of inquiry that includes theoretical ideas about why things are as the observations suggest.

Figure 13.1 shows two imaginary theories (Theory A and Theory B) competing with one another. As the diagram shows, both theories accurately predict Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3. However, unlike Theory A, Theory B also accurately predicts Hypothesis 4. Thus, Theory B would be considered the more elegant of the two theories.

The main reason for using figure 13.1 to illustrate the idea of competing theories rather than an actual example is that most ‘‘real-world’’ examples are much more complicated. For instance, one theory may be more emphatic than another theory regarding a particular hypothesis. Another possibility is that some hypotheses may be confirmed by one study but refuted by another.

Simplicity

Suppose two theories are essentially equal in predictive accuracy and scope, but one is much easier to understand than the other. In this case, the theory that is easier to understand is considered more elegant. This criterion of simplicity is also called parsimony and Occam’s razor. This latter term credits an eighteenth-century scientist, named William of Occam, who devoted much of his professional career to trying to boil scientific theories proposed by others down to their bare essence (Dewsbury, 1984, 187).

Falsifiability (or Absence of Ambiguity)

As noted earlier, theories can never be proven true in a strict empirical sense. If a theory could be proven, it would no longer be a theory! Nevertheless, theories vary in how easily they can be dis proved. Disproof is achieved by deriving one or more hypotheses from a theory that persistently fails to match empirical observations. In other words, the best one can say on behalf of a scientific theory is that it has not yet been disproven.

Obviously, a theory can be so ambiguous that it is impossible to disprove (Shearing, 1973). An ambiguous theory, however, is not considered elegant because it is not vulnerable to disproof (Lakatos, 1970). Theories that are very precise in terms of leading to many testable hypotheses are said to have the greatest degree of falsifiability, and falsifiability is a very desirable element in a well-formulated scientific theory (Ember & Ember, 1988, 197; Popper, 1935).

Compatibility

Assume that you have two competing theories of the same phenomenon, neither of which has been well tested yet. However, one theory is compatible with other theories of related phenomena that have been found to generate accurate hypotheses, and the other theory is not compatible with these other theories. In this case, all else being equal, the first theory would be considered better than the second.

Aesthetic Appeal

Many of the world’s most theoretically oriented scientists have reported that one criterion they use to develop confidence in their theories involves a sense of beauty (Chandrasekhar, 1987; Clark, 1971, 87; Forward, 1980). An aesthetic sense alone is not very helpful for scientifically explaining the empirical world, but when combined with the other components of elegant theorizing, an aesthetic sense can be valuable in theory construction.

To encourage all scientists to be imaginative and artistically creative in scientifically conceptualizing all aspects of life, including behavior, a famous biologist once wrote ‘‘the universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose’’ (Haldane, 1927). Ultimately, theory construction provides an arena in which science and artistic creativity often embrace (Judson, 1980).

HOW THEORIES FIT INTO THE RESEARCH PROCESS

Because scientific theories exist at levels of abstraction beyond what can be empirically verified, the only way theories can be tested is by deriving hypotheses from them and then testing these hypotheses. Figure 13.2 provides an idealized sketch of how theories and hypotheses fit into the scientific research process. Beginning at the top and proceeding clockwise, we assume that a theory has been proposed. Then, one or more hypotheses are derived from a particular theory. The hypotheses are then empirically tested, and, on the basis of those tests, generalizations are made about the nature of reality. From these generalizations, scientists sometimes fine-tune the original theory; other times, they may replace it with another theory. Thereby, new rounds of hypothesis-testing can be set into motion. In reality, things are much more complex and chaotic than figure 13.2 implies, as the process of testing several different theories often proceeds over the course of several decades.

A Theory is Like a Fruit Tree

A useful way to think about scientific theories is that they are like fruit trees. In the case of trees, those that bear lots of eatable fruit are better than those that are barren or those that produce fruit that is rotten or unpalatable. For scientific theories, those that lead to the greatest number of hypotheses are better (more elegant) than theories that make few, if any, testable predictions. Of course, if most of the hypotheses generated by a theory fail to be confirmed empirically, that is not good news for the theory, either. So, for a scientific theory to be deemed elegant (or to say that it has merit), it should generate many empirically testable hypotheses, all (or nearly all) of which should be confirmed.

SCIENTIFIC MODELS

In scientific theorizing, the term model is usually used to refer to some type of simplified representation of some aspect of a theory, although some have used the terms model and theory interchangeably (Coleman, 1964, 528; Hall & Hirsch-man, 1991; Phillips, 1966, 59; Simon, 1969, 37). Even the concept of model and hypothesis have been used as if there were no difference between them (Ekman 1990, 244). Here, distinctions between these three concepts—theories, models, and hypotheses—are maintained.

The distinction between a model and a theory is as follows: Whereas a theory puts forth an explanation in linguistic form, a model puts forth an explanation in a more tangible or physical form. In addition, a model is often used to illustrate and clarify one or more special aspects of a scientific theory, rather than representing a theory in its entirety (Sienko & Plane, 1976, 132).

Three types of models are used in the social sciences: diagrammatic (or structural) models, equational models, and animal models. Each one is described and illustrated in the following sections.

Diagrammatic (or Structural) Model

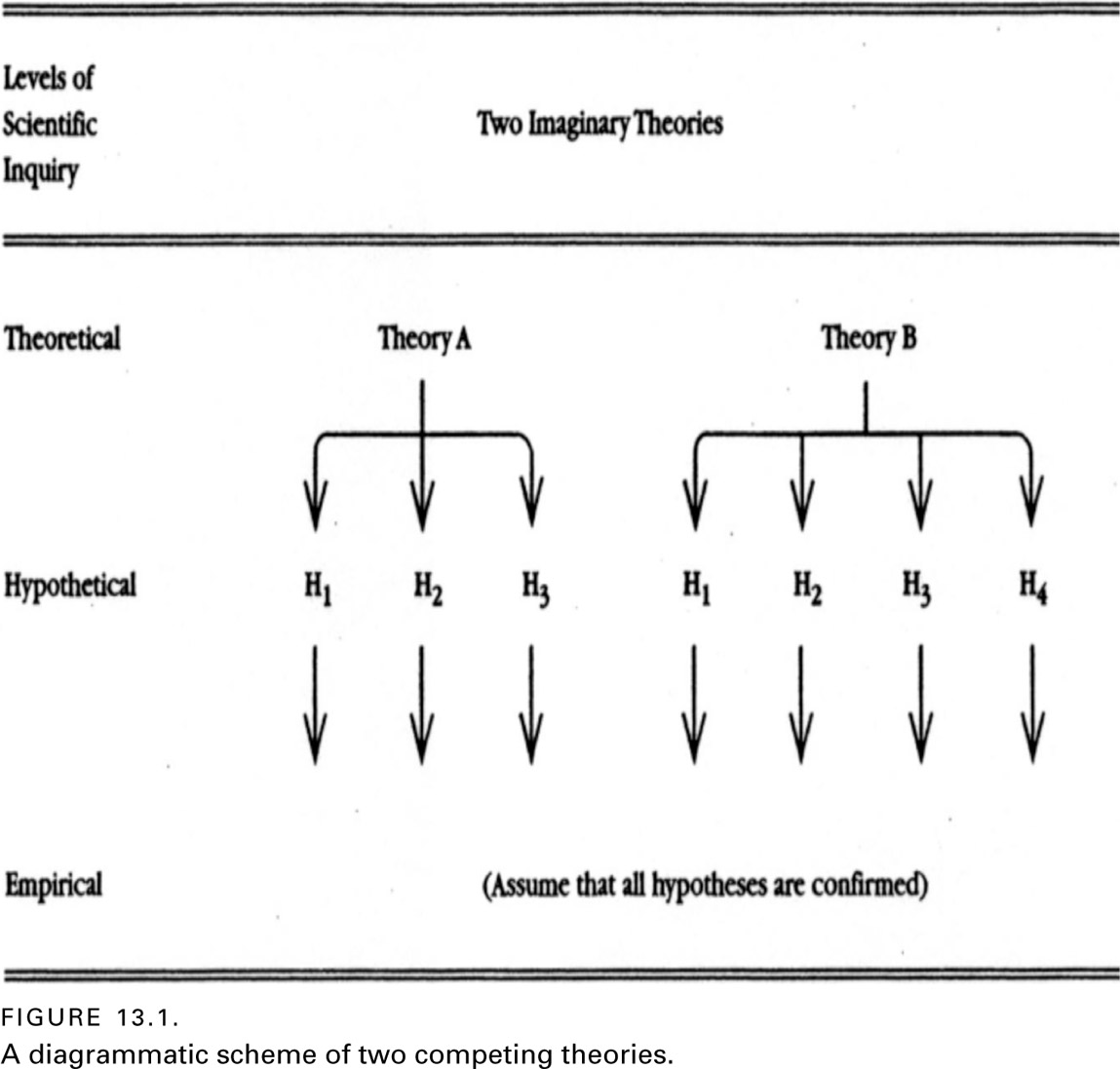

A diagrammatic (or structural) model is one in which a geometric sketch (or sometimes an actual physical object) is used to help illustrate a theory. Figure 13.3 provides an example of a diagrammatic model of how the use of various recreational (as opposed to therapeutic) drugs among teenagers may escalate to the use of additional recreational drugs and sometimes even to drug addiction (Brook et al., 1990, 159). This model can be understood apart from any specific theory of drug use, although it may certainly be incorporated into a theory as well.

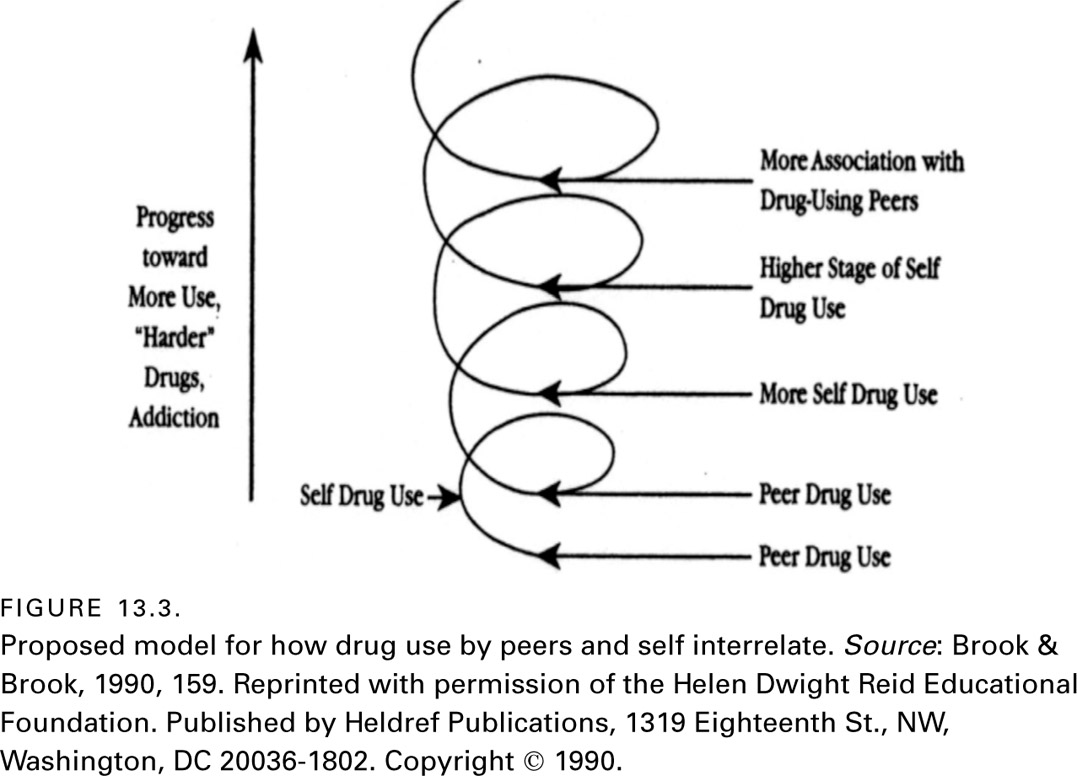

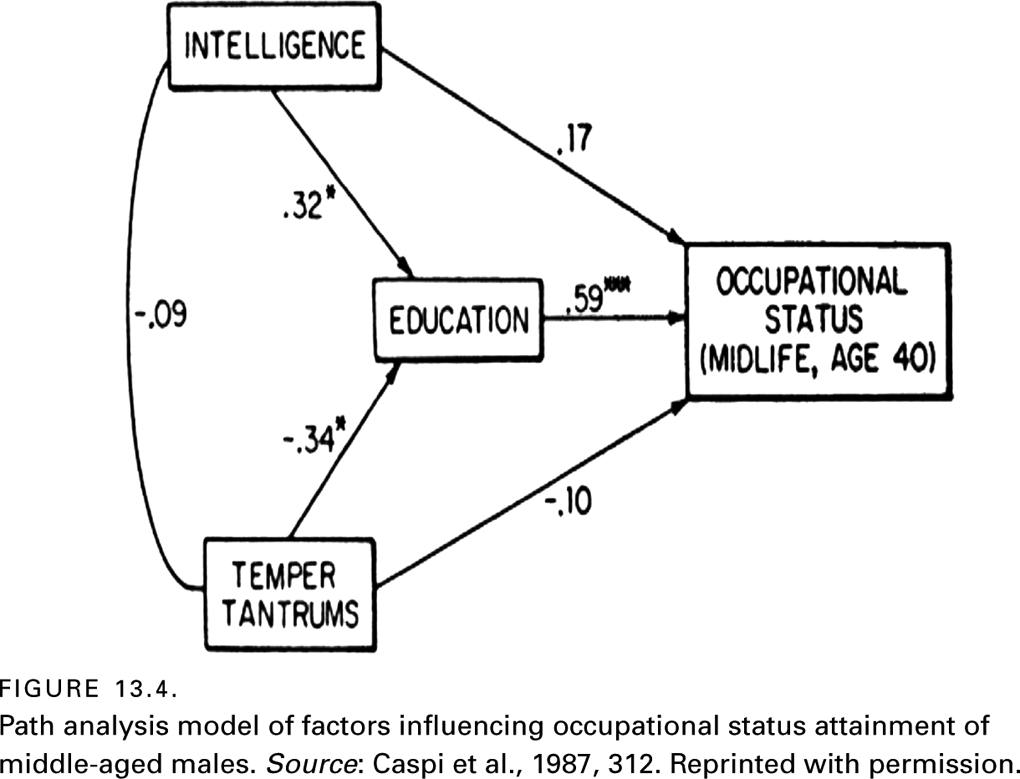

Sometimes diagrammatic models are produced by computers based on a statistical analysis of some large data set. The most common example of such modeling is a type of multivariate statistic called path analysis. In such a modeling procedure, a researcher usually identifies variables in terms of their temporal sequence, and then instructs a computer program that performs path analysis to configure a causal scenario, complete with coefficients that identify the strength of each variable in the causal chain.

Figure 13.4 presents an example of a diagrammatic model based on path analysis. This analysis was performed on data that followed a large sample of males from childhood through age 40, measuring a large number of behavioral and social variables for over three decades. Using a type of multivariate correlational techniques, the researchers were able to test their theory that childhood variables can substantially impact occupational status in adulthood.

According to the computer-generated model shown in Figure 13.4, three antecedent variables were particularly important in affecting men’s occupational status. Two of these variables were measured in childhood: intelligence and the frequency of temper tantrums. Most of the effects of these two variables influenced the number of years of education the subjects obtained. Educational attainment, in turn, had a strong effect on occupational status attainment. Notice that the coefficients between each variable suggest the strength of each variable’s impact on, or association with, each of the other variables.

Equational (or Mathematical) Model

Equational forms of scientific models are most commonly found in the physical sciences such as physics and astronomy, but a few examples from the social sciences can be given. Probably the most far-reaching equation used by social scientists was one first proposed in the 1960s by an American biologist, named William Hamilton (1963, 1964). He proposed an equation to help explain altruism, which refers to self-sacrificing behavior by one individual on behalf of another. Careful observations have revealed that altruistic behavior is found not only in humans, but in many other social animals as well (Hebb & Thompson, 1954; Krebs, 1971). The most frequently documented cases of altruism involve the committed care and protection by parents on behalf of their offspring (Wittenberger, 1981, 75).

Hamilton’s formula for altruism was initially inspired by the observation that worker honeybees (who are sterile females) will selflessly die in defense of the hive. The theory on which the formula rests is an updated version of Darwin’s theory of evolution (i.e., one incorporating genetic concepts). This neo-Darwinian theory implies that worker bees are genetically so similar to the queen (who is their sister) that workers have evolved the propensity to sacrifice themselves on behalf of the queen, and thereby ensure the perpetuation of their own genes. In other words, even though the worker bees are sterile, they are able to transmit their genes to future generations by assisting the queen in her very prolific reproduction. According to Hamilton’s model, reproducing indirectly by helping close relatives reproduce has given rise to altruism in many species. He termed this phenomena kin selection as an extension of what Darwin termed natural selection (Brown, 1991, 105).

Hamilton expressed his theory with the following equation:

P(Altruism) bt (r) > c

where

P(Altruism) represents the probability of altruism

bt is the potential reproductive benefit for an altruistic act

r is the degree of genetic relatedness between an altruist and a potential recipient

c is the probable reproductive cost (or risk) to the prospective altruist

This equation suggests that the probability of an altruistic act being exhibited by one animal toward another depends in part on the number of genes they share in common and the potential of the recipient of the altruistic act to subsequently transmit these genes to future generations (Peck & Feldman, 1988). Another factor is the risk to the altruist, with the highest risk being reserved for recipients with the closest genetic relatedness.

Most other equational models in the social sciences are found in the fields of economics and demography. Equational models have been developed for predicting upswings and downturns in national economies (Bradley et al., 1993), and shifts in societal birth and death rates (Ahlburg, 1986; de Beer, 1991; Hapke, 1972). Most of these models are derived from empirical information that certain variables tend to rise and fall in a specific pattern, and that they tend to follow increases and decreases in other variables.

An equational model has been developed for predicting the onset of cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and even sexual activity among adolescents (Rowe & Rodgers, 1991; Rodgers & Rowe, 1990). To make these predictions, the model assumes that these behavior patterns often spread like epidemics: The more one’s peers engage in these acts, the more the next generation of adolescents will do likewise.

Animal Model

An animal model results from locating behavior in various nonhuman animal species that resembles some aspect of human behavior. The methods used to demonstrate that some type of behavior is at least roughly equivalent across various species usually involves combining science with intuition, similar to the processes surrounding the assessment of a measure’s validity and reliability.

One area of animal modeling in which one of the authors of this text has been involved is in the field of criminology. Many researchers who observe animal behavior have witnessed ‘‘virtual criminal offenses’’ in nonhuman species. For example, there have been photographs taken of behavior that in humans would be considered both sexual assault (forcible rape) and homicide. These photographs reinforce the idea that a nonlegal equivalent of crime may exist outside the human species (Ellis, 1998). Whether the causes of offending in humans are in any way similar to the causes of the modeled behavior in other species is an empirical question requiring research attention.

Three factors are responsible for the widespread use of animal models in the social sciences and criminology: First, researchers are under fewer ethical restraints when performing experiments on nonhumans than on humans. Second, it has become increasingly apparent that humans and other animals share a common biological heritage with one another (including similarly configured brains). This suggests that science can learn a great deal about human behavior by studying the behavior of other species (Alcock, 1993; Rajecki, 1983; Releth-ford, 1990; Strum, 1987). Third, because the causes of human behavior are usually more complex, it is often easier to identify some of the most basic causes of a behavior pattern in nonhumans before giving full attention to humans (Alonso, Castellano, Afonso, & Rodriguez, 1991, 69). Nevertheless, cross-species parallels can always be overdrawn, and must always be tempered with the realization that all species are at least somewhat unique.

Knock-Out Mice: A Model for Human Criminality?

Research has consistently shown that on average offenders with long rap sheets have unusually low levels of an enzyme called monoamine oxidase (MAO) (Ellis et al., 2009, 205). The function of this enzyme in the brain is to help regulate some of the key neurotransmitters such as serotonin. Recently, researchers were able to isolate the actual gene controlling one form of MAO in mice. Then they removed the gene from mice embryos, creating so-called MAO knock-out mice. Figure 13.5 shows two of these genetically modified mice. Unlike most mice who are relatively peaceful, MAO knock-out mice spend about half of the time they are together fighting. Scientists are hoping to develop and test new drugs on these mice that will help prevent their excessive aggression. One day, some of these drugs may be used to treat unusually violent humans. Overall, knock-out mice are an interesting example of an animal model for human violence.

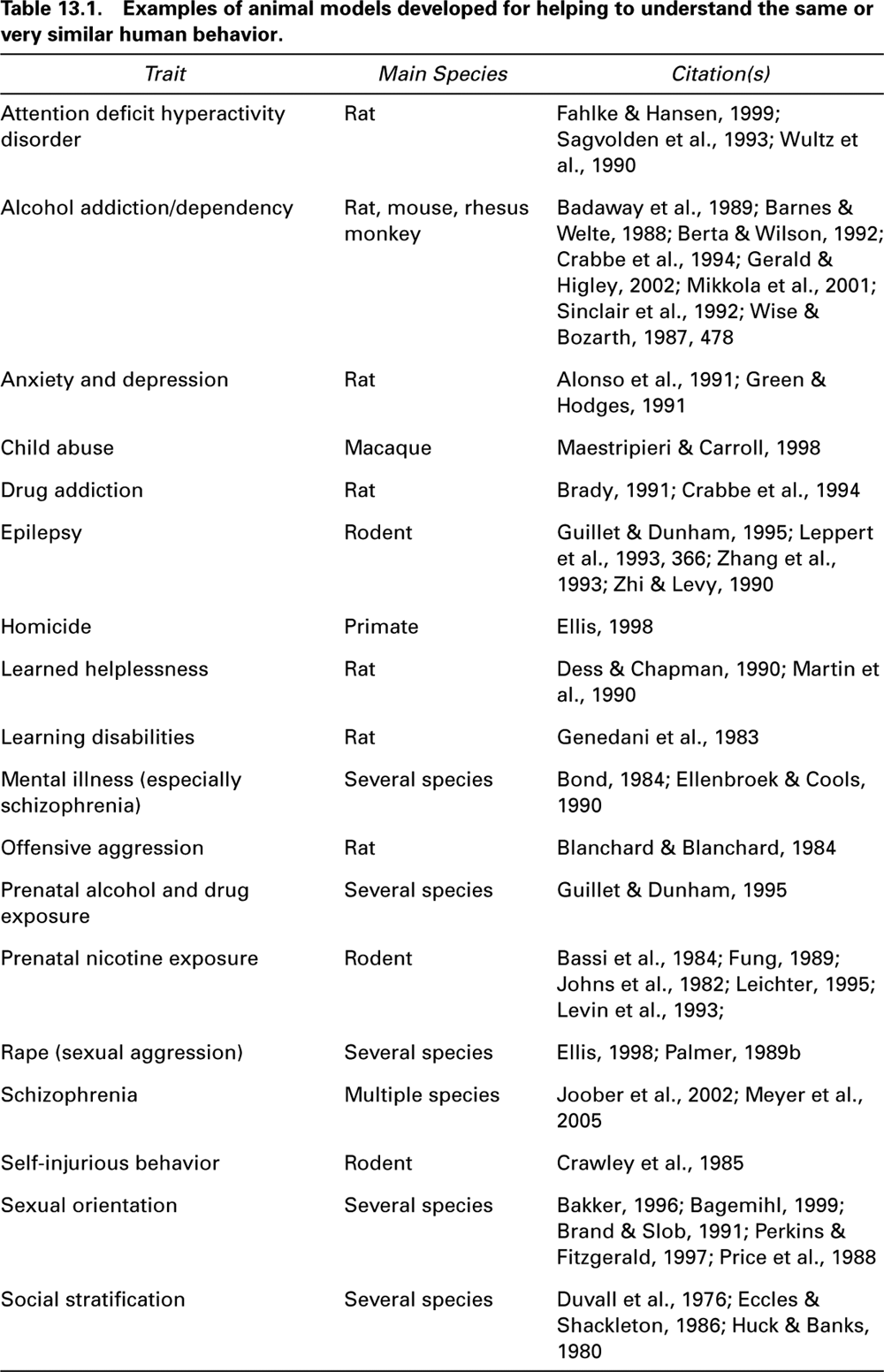

Nonhuman animal models have been identified for a wide range of human behaviors, emotions, and even mental illnesses. Included among currently identified animal models are those listed in table 13.1.

Got a Sweet Tooth? Extending an Animal Model for Alcoholism

When given a choice between plain drinking water and water with 15 percent alcohol, most rats prefer plain water, but a small percentage quickly develop a distinct liking for the water laced with alcohol, and eventually exhibit considerable agitation if the alcohol is withheld. Studies indicate that these preferences have an intergenerational continuity among inbred strains, suggesting that they are influenced by one or more genes (Barnes, 1988; Wilson et al., 1984). This research is interesting in light of research among human twins and adoptees, suggesting that alcoholism also has a genetic component (Cadoret et al., 1996; Heath et al., 1991; McGue et al., 1996; Sigvardsson et al., 1996). (The research methodology surrounding twin studies and adoption studies is explored in chapter 14. Many of these studies have been applied to the study of criminality and closely related phenomena.)

Along with searching for genes conducive to alcohol dependency that are shared by rats and humans, researchers have noticed that alcohol-preferring rats have stronger preferences for sweets than alcohol-avoiding rats (Gosnell & Krahn, 1992; Kampov-Polevoy et al., 1995; Sinclair et al., 1992). This evidence encouraged a team of Russian scientists to look for similar patterns in humans. As with alcohol-preferring rats, human alcoholics also have a significantly elevated preference for sweets, encouraging speculation that at least one of the genes contributing to alcoholism also affects cravings for sweets (Kampov-Polevoy et al., 1997, 2001).

Work with mice has also turned up strong evidence of genetic susceptibility to alcohol dependence (Badaway et al., 1989). These studies suggest some similarities in brain biochemistry between alcohol-dependent mice and human alcoholics (Comings et al., 1991, 306). Of course, no one believes that alcohol-preferring strains of rats and mice are like human alcoholics in all respects, but the similarities may be sufficiently close for the animal models to gradually shed light on human alcoholism.

Animal Models: Proceed with Caution

While animal models are helping social scientists and criminologists understand human behavior, the uniqueness of each species should always be recognized. A couple of instances in which animal models appear to be inappropriate are as follows: One instance involves the study of gender differences in alcohol consumption. Studies of humans throughout the world have indicated that males tend to drink more than females do (Cartwright et al., 1978; Fillmore et al., 1991; Hilton, 1988b; Mercer & Khavari, 1990; Romelsjo & Lundberg, 1996, 1317), but in rats who drink, females consume more than males (Lancaster & Spiegel, 1992; Mankes et al., 1991).

Another instance in which an animal model appears to be at least partially inappropriate involves impulsive aggression. Studies have suggested that low levels of a neurotransmitter called serotonin is related to such aggression in humans (Brown et al., 1990; Coccaro & Kavoussi, 1996) and in other primates (Higley et al., 1990; Mehlman et al., 1995). However, studies of rodents have reported the opposite pattern (Bell & Hobson, 1994; Korte et al., 1996; Olivier et al., 1990).

Overall, researchers always need to be on guard against overgeneralizing across species, and should certainly never equate humans and other animals (Abelson, 1992). Also, simply because animal models appear to exist for many aspects of human behavior, models for many other aspects of human behavior may never be found. Finally, keep in mind that not all social scientists who study other animals do so to better understand humans. The study of behavior of non-human animals can be fascinating and informative in its own right.

To summarize, there are three distinct types of models used in the social sciences: diagrammatic, equational, and animal models. Models resemble theories in the sense that both are used to present an organized conceptual picture of some phenomenon. However, whereas theories are typically expressed linguistically, models appear in a variety of largely nonlinguistic forms. Another point worth noting is that a scientific model is sometimes used to represent only a portion of a theory rather than the theory in its entirety.

SCIENTIFIC LAWS

A concept that can be distinguished from a scientific theory is that of a scientific law. A scientific law is a statement about what should always occur under a precise set of conditions. The best known scientific laws come from the physical sciences, such as Newton’s law of gravity. This law states that the speed of an object in free fall (possible only in a complete vacuum) will accelerate at a very specific rate. There are no commonly recognized laws in the social sciences. Why? The main reason is that under current understanding, both individual and collective behavior are so complex as to defy prediction with the degree of precision expected of scientific laws (Coleman, 1964, 26).

The difference between a scientific law and a scientific theory is that a law offers no specific explanation for what it is intended to predict. Scientific laws are merely statements about what will be observed under a specific set of conditions. Hypotheses are like laws except that hypotheses are usually tested within much broader limits of probability than is the case for scientific laws.

SCIENTIFIC PARADIGMS

In the early 1960s, Thomas Kuhn (1962) published a widely read philosophy of science book in which he argued that scientists in each major discipline usually work for decades without agreeing on a common paradigm. A paradigm refers to a set of assumptions about the nature of the phenomenon to be explained and the approach that will be taken to obtain those explanations (Simberloff, 1976, 572). Paradigms are best thought of as more general and encompassing than theories; in fact, they are the broadest perspective within which all theories are thought to emanate.

Kuhn contended that at some point during its pre-paradigm stage, a discipline will have accumulated enough basic knowledge that someone within the discipline will propose a new perspective that will spark a paradigmatic revolution. This revolution may last for decades, but will sooner or later transform the discipline into what Kuhn calls normal science. By this, Kuhn means that nearly all the scientists working in a particular discipline will settle on a common approach to the understanding of the phenomena they study.

Scientists in most of the physical sciences seem to have had their paradigmatic revolution, and have now settled into normal science (McCann, 1978). This means that the main disputes among physicists, chemists, and the like are no longer about how to approach their disciplines but about detailed substantive issues.

What about the social sciences and criminology? Most students only need to take courses from more than one instructor to know that the social sciences are all still in the pre-paradigm stage of development (Bauer, 1992, 133; Jeffery, 1977, 10; Weingart, 1986; Wilson, 1980, 4).

HYPOTHESIS TESTING AND ATTEMPTS TO GENERALIZE

Having made distinctions between scientific hypotheses, theories, and models, we can return to an important topic first mentioned in chapter 3: hypothesis testing. Recall that in every study, two opposing hypotheses can be tested: a research (or alternative) hypothesis and a null hypothesis. Even though scientists are nearly always more interested in testing a research hypothesis than an opposing null hypothesis, the latter is always being tested by implication. Let us now extend the concept of hypothesis testing by illustrating how researchers go beyond testing specific hypotheses and attempt to make sweeping theoretical generalizations.

Universes as a Whole, Local Universes, and Samples

Suppose a particular theory leads a researcher to expect that females will have some characteristic (trait X) to a greater average degree than males. Furthermore, assume that the theory implies that trait X should be higher for females than for males not only in a few contemporary societies, but for all times and in all societies. The implication then is that the universe (or population) referenced by this particular theory includes all humans throughout the world who have ever lived and will ever live.

Such a theory would be desirable from the standpoint of its theoretical elegance, since its predictive scope would be very broad. However, consider the difficulties one would have in testing this theory. Obviously, it would be impossible to draw a random sample from the entire universe. The best a researcher can do will be to draw samples from a few societies during the three or four decades of his or her career. Such sampling limitations confine a researcher to what is called the local universe, as opposed to the universe as a whole. In other words, even though the theory is stated very broadly in terms of the universe as a whole, all efforts to test it will be based on samples drawn from local universes.

The distinction between a universe as a whole and samples drawn from a local universe is illustrated in figure 13.6. Notice that other researchers, working at other periods of time or in other areas of the world can assist in testing the generality of the theory by sampling other local universes. Through this process, the full extent to which the theory does or does not reflect empirical reality can be gradually assessed. Nevertheless, because of the haphazard and opportunistic nature of sampling, a broad ranging scientific theory can never be fully tested, even if all the samples happen to have been representative of the local universes from which they were selected.

To reiterate an important point about hypothesis testing, many scientific theories relate to universes that are much broader in time and space than any one researcher can ever hope to sample. Nonetheless, each sample drawn from a local universe to test one of the theory’s hypotheses is valuable. After dozens of studies of several hypotheses derived from a theory, scientists are usually in a fairly good position to pass judgment upon the elegance of a particular theory.

The Null Hypothesis and Type I and Type II Errors

Building on the concept of hypothesis testing, two types of error with reference to the null hypothesis need to be recognized. Recall that the null hypothesis is a standard benchmark hypothesis that asserts that there is no difference or no relationship with respect to whatever is being studied.

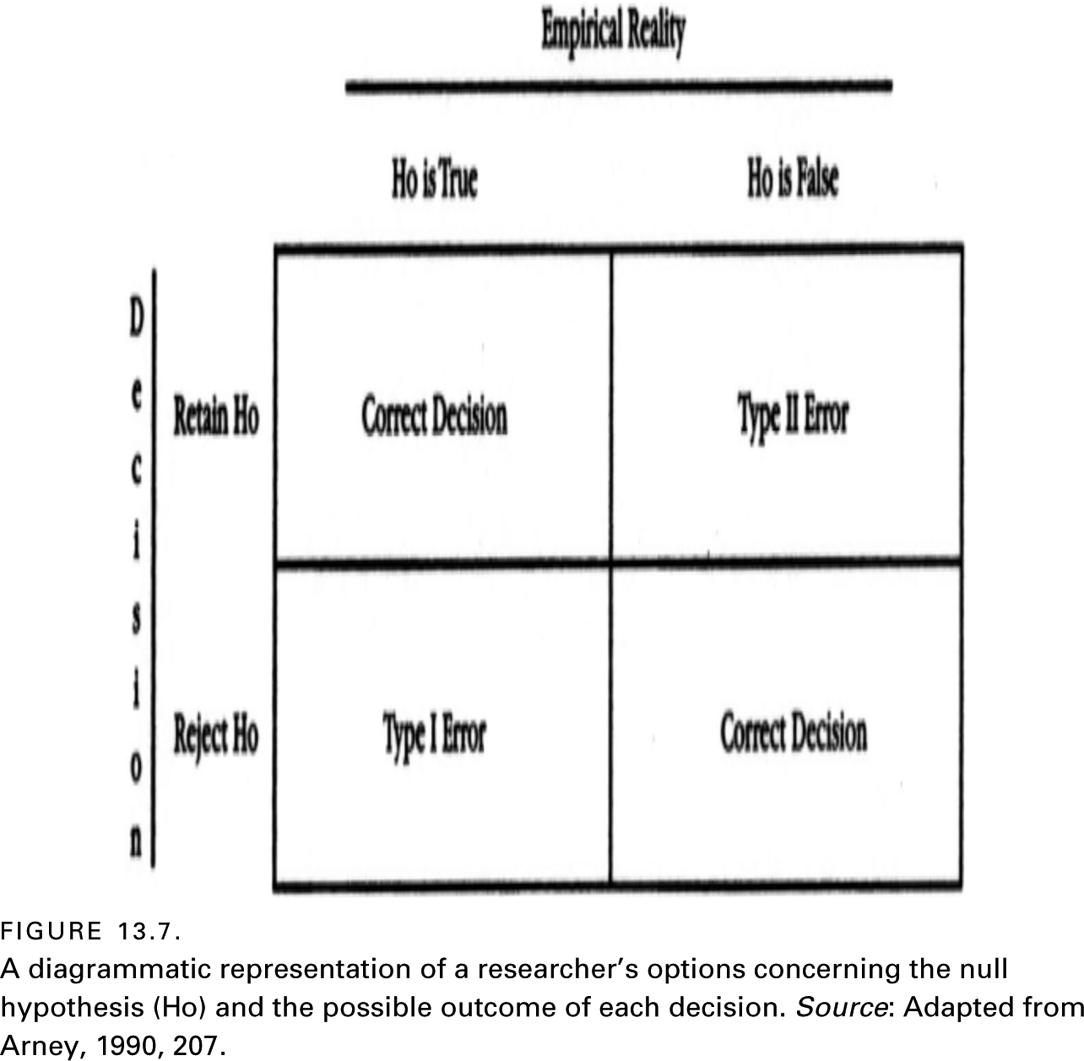

The two possible errors are known as Type I error and Type II error, and they are illustrated in figure 13.7. A Type I error involves rejecting the null hypothesis when it is in fact true, and a Type II error is defined as accepting the null hypothesis when it is actually false. (To keep them straight, students may want to memorize the nonsense rhyme ‘‘Type I reject null, Type II accept null.’’)

These two concepts underscore the inherent fallibility of the scientific process as individual hypotheses are tested. Recall that when scientists test hypotheses, they will normally risk up to a 5 percent chance of making an erroneous decision about the acceptance or rejection of a hypothesis. It is this degree of risk that is denoted by Type I and Type II errors. Despite the ever-looming risk of one or the other of these errors every time a hypothesis is tested using a sample, scientists must bear in mind that no hypothesis stands or falls on the basis of a single study.

At the bottom line of hypothesis testing is whether the hypothesis is derived from a theory or an idea that ‘‘came out of the blue’’; such testing always has risks of leading to an erroneous inference. If one decides to reject the null hypothesis and accept some alternative, a Type I error is being risked, and if one decides to accept the null hypothesis, a Type II error is being risked. The only way to avoid making these errors is to study the entire universe. For most phenomena of theoretical interest, the universe is much too large, both in time and space, to be studied in its entirety.

CLOSING REMARKS REGARDING SCIENTIFIC THEORIZING

It would be difficult to exaggerate the importance of theorizing and hypothesis testing in the social sciences generally and for criminology specifically. These concepts are at the heart of the scientific method. Theories help scientists integrate information that has already been learned and they suggest new possibilities worth considering. Because most theories are highly abstract, hypotheses are used to connect theories to the ‘‘real world.’’

When compared with some of the physical sciences in which clear paradigms have formed, most social science theories currently pale. Recognition of the primitiveness of social or behavioral theories has led some to a feeling of what has been termed ‘‘physics envy,’’ given that physics seems to represent the epitome of scientific sophistication and theoretical maturity. Nevertheless, progress is continually being made in the social sciences with the results of thousands of hypotheses being reported every year. As these findings mount, theories are bound to become more elegant.

SUMMARY

Scientific research can be conducted without any theoretical guidance, but the results of such research are often difficult to organize and interpret. Ultimately, theories make it easier for scientists to integrate and to comprehend findings from massive amounts of scientific research.

This chapter focused on illuminating the nature of scientific theorizing and hypothesis testing. It was noted that scientific theories are formulated to cover such a massive number of events that it is unrealistic to ever attempt to completely test these theories. Nevertheless, if several studies of several different hypotheses derived from a particular theory are confirmed, this can be considered substantial evidence in favor of a theory.

This chapter pointed out distinctions between such terms as empirical observations, hypotheses, and theories. If there are such things as ‘‘facts’’ in science, they are the empirical findings documented in research reports. But, unlike facts in ordinary discourse, scientific facts are tentative, always awaiting additional confirmation (or refutation) by those who conduct other studies.

Hypotheses are statements about empirical reality, which may or may not be true. Sometimes hypotheses come to a researcher ‘‘out of the blue,’’ but generally they are derived from some theory. As suggested by figure 13.1, a theory exists ‘‘above’’ empirical reality. Theories become connected to empirical reality when numerous hypotheses derived from them are confirmed by empirical observation.

Scientific theories are judged most importantly on their predictive accuracy and predictive scope. Other criteria are simplicity, falsifiability, and aesthetic appeal.

Scientific models include a host of special ‘‘tools’’ used by scientists to conceptualize reality. Although the terms theories and models are sometimes used interchangeably, a distinction is warranted. The most common difference is that theories are usually presented in linguistic form, whereas models are presented in some nonlinguistic form. Three categories of scientific models were identified: diagrammatic models, equational models, and animal models. Diagrammatic (or structural) models are presented in physical figures, including computer-generated models, such as in path analysis. Equational models use a mathematical equation to express a way of understanding some phenomenon or forecasting future events. Animal models have been used increasingly in the social sciences and criminology in recent years, partly because of growing evidence of the close genetic and neurological similarities between humans and other species (especially other mammals).

Scientific laws are statements that specify the conditions under which some outcome will occur. It was noted that scientific laws are rare in the social sciences relative to the physical sciences.

In hypothesis testing, two types of errors are possible, both of which are normally stated in terms of the benchmark null hypothesis. The Type I error involves incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis, while the Type II error involves incorrectly accepting the null hypothesis. Scientists typically risk no more than a 5 percent probability of making either of these errors when testing hypotheses.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Chandrasekhar, S. (1987). Truth and beauty: Aesthetics and motivations in science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (In every generation of scientists, there are a few who become passionate about their work at fundamental theoretical levels. Read about what motivates them in this book.)

Curtin, D. W. (Ed.). (1980). The aesthetic dimension of science. New York: Philosophical Library. (Consists of five chapters written by scientists regarding how the search for beauty and for understanding commingle.)

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (This is a widely cited book about the ways in which new scientific paradigms replace old ones through the maturation of science in various areas.)

Lastrucci, C. L. (1963). The scientific approach: Basic principles of the scientific method. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman. (A classic book on the basic description of the scientific method, especially as it pertains to the integration of research and theory.)

Rencher, A. C. (1995). Methods of multivariate analysis. New York: Wiley. (Contains clearly written information about path analysis and its interface with hypothesis testing and theory construction.)

Skinner, Q. (Ed.). (1985). The return of grand theory in the human sciences. New York: Cambridge University Press. (Recommended reading for those interested in exploring the many facets of theorizing in the social and behavioral sciences, especially at high levels of abstraction.)

Willner, P. (Ed.). (1991). Behavioural models in psychopharmacology: Theoretical, industrial and clinical perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (This book provides several examples of animal models for the study of human behavior and mental health conditions.)

Social science journals that specialize in theory formulation and theory testing are:

Criminology

Criminology and Public Policy

Social Problems

Psychological Review

Sociological Theory

Theory & Psychology