Of all writers at the time, John De Forest saw the most action as a Civil War soldier. By his account, including service in war and peace, “I was six and a half years under the colors. I was in three storming parties, six days of field engagements, and thirty-seven days of siege duty, making forty-six days under fire.” Through it all he kept writing: letters home, journal entries, essays for literary magazines, the beginnings of a novel. Ten years after the war, William Dean Howells, editor of the Atlantic Monthly praised De Forest as “the first to treat the war really and artistically.”1

Nothing he had published before the war suggested such acclaim. Sickly as an adolescent, the New Haven native spent much time traveling abroad. He sampled assorted spas and water-cures in hopes of revitalizing his health. On the eve of the Civil War, De Forest’s literary output consisted of his History of the Indians of Connecticut from the Earliest Known Period to 1850 (1851), two travel books, Oriental Acquaintance (1856) and European Acquaintance (1858), and two novels, “Witching Times” (serialized in Putnam’s Monthly Magazine beginning in 1856) and Seacliff (1859). Only this last work received any attention; a reviewer in the Atlantic Monthly praised it as a “very readable novel, artful in plot, effective in characterization, and brilliant in style.”2

Just months prior to the firing on Fort Sumter, De Forest was in Charleston, South Carolina, visiting his wife, whose father was a professor at Charleston Medical College. In an essay titled “Charleston Under Arms,” he assessed the mood of the region. He condemned the South for laboring under assorted delusions, but he did so without deriding Southerners. Charleston was a “persuaded, self-poised community,” just like Boston only on the opposite side of the slavery question. In the essay, De Forest found his voice as narrator and reporter. By turns analytical and sardonic, De Forest would continue throughout the war to probe the dimensions of conflict he first observed here: “fighting was a sober, sad subject; and yet at times it took a turn toward the ludicrous.”3

“Charleston Under Arms” appeared in April 1861. On January 1, 1862, De Forest was commissioned a captain of Company I of the Twelfth Connecticut. As with so many other chronically ill young men, war provided De Forest with an opportunity to refashion himself into an energetic and fearless officer. His writings reveal considerable talents as observer, story-teller, and scene-setter. He was no blind patriot and he never lost sight of his “character as novelist.” If anything, there is too much posturing, too heavy a persona, in the material that came out of his experiences during the war. But he never flinched from trying to describe the ambiguities and uncertainties of human behavior and that is what continues to give this work such vitality.

Though late in his life, De Forest began to assemble his writings from the Civil War and Reconstruction, which were not published until after World War II. In addition to A Volunteer’s Adventures: A Union Captain’s Record of the Civil War (1946), De Forest’s experiences as Freedmen’s Bureau agent in Greenville, South Carolina are recounted in A Union Officer in the Reconstruction (1948). De Forest’s non-fiction prepared the way for his fiction: with Miss Ravenel’s Conversion from Secession to Loyalty (1867), he achieved the literary fame that had eluded him until then. William Dean Howells applauded the work, and even Henry James, who thought it a poorly constructed novel, praised it for its realistic depiction of war.4

The fame did not last. Miss Ravenel’s Conversion sold poorly and De Forest turned away from realism. Through the 1870s, he published nearly a novel a year, works that have garnered far more attention in our time than in his. In 1898, a reporter from the New York Times visited De Forest, whose “name suggests little to the reader now,” yet “thirty years ago he was a famous writer, as famous as any in America in his time.” By the end of the century, De Forest had abandoned fiction. He devoted himself to the study of ethnology. His focus, however, was not on the characteristics of blacks and whites, as one might have expected from a New England intellectual who spent much time in the South. Rather, he was looking back at the historical origins of his own people.5

In 1902, De Forest applied for a Civil War pension. He lived alone in a third-floor room at the Hotel Garde in New Haven. Indigent and failing in health, he was awarded $ 12 a month by the Pension Board. “I am closing up my literary life,” he declared.6 For a writer, that meant closing up life itself. He declined rapidly and died in his son’s home on July 17, 1906. He rests in Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven, his place marked by a tombstone bearing saber and pen.

… Personally I am more comfortably situated than I expected to be. I have got out of the hole where I was lodged at first, and am in a tolerable stateroom beside the stairway, only objectionable as being too near the boiler and also not quite large enough for three. Even the soldiers are much better accommodated than I supposed when I last wrote you; there is room enough below for every man to stretch himself at full enough in his blanket or overcoat. Some of them were comically surprised and indignant when they learned that they were not to be made free of the afterpart of the ship. “That’s a pooty way to treat a poor soldier!” whines one gawky lout as the sergeant of the guard, an old regular, routed him out of a seat on the quarter-deck and hustled him forward.

Not a woman on board; the ship is as the world was before Eve was created; the most jealous of wives need not be afraid to have her husband here. I am as indolent as passengers usually are; I cannot even study my drill book and the regulations. I smoke like a Turk; I walk the deck till the broiling sun sends me up to the breezy top of the wheelhouse; I load my revolver and shoot at gulls or floating tufts of seaweed; in my best estate I play at checkers on the quarterdeck. The cabin is so hot and close that it is not pleasant to linger there.

The general indifference to our future is curious and makes me wonder if we are beginning to be heroes. Nobody knows where we are ultimately going, and nobody appears to care. We vaguely expect to follow Porter’s mortar fleet and occupy some place which has been shelled into submission.8 It seems impossible as yet to believe that we peaceful burghers are going to fight. You must not suppose that this tremulous handwriting results from terror of coming battle. It is merely the ship’s engine shaking the table.

Why were we born! Just imagine a regiment landing on a desert island without baggage wagons and horses, without tents enough, and without even a tent pin to kindle a fire with! Every day I detail from a quarter to three quarters of my company to collect wood for cooking; and this wood they must bring on their backs a distance of two, three, and four miles. We have no cook-tent, and no lumber wherewith to build cook houses, so that I must store all the rations of my company in my own tent. Consequently I am encumbered with boxes of hardbread, and dispense a nutritious perfume of salt pork, salt beef, onions, potatoes, vinegar, sugar and coffee….

A southerly gale commenced and by afternoon blew violently…. By nightfall the gale became a thunderstorm which deluged the camp and upset many tents. The pins of mine pulled out of the wet sand as if it had been butter, and the whole thing went prostrate with a hateful soft swish. As raising it in that tempest was out of the question, I plunged into the tent of a neighboring captain and slept on his floor. No harm resulted to health and very little to property. This reminds me to say that the general sanitary condition on the island is wonderfully good. The Ninth and Twenty-sixth have not had a death during their four-months’ stay, so that if we hold on here and let the Rebs alone we may all become centenarians.

Three Western regiments joined us lately, making ten regiments now on the island besides a troop of cavalry and a battery of artillery, in all above nine thousand men. Nearly every day there are arrivals of transports, mortar boats, gunboats and ships of war. The naval officers tell us that this is to be a large expedition, and that there will be fully twenty-two thousand men of the land forces alone. If this is true, I infer that we are going to New Orleans, and that we are not likely to start immediately.

Today we have for the time seen the mainland distinctly; it is a low, farstretching coast, apparently covered with forests. A mirage lifts it in the air so that there is a bar of steel-color between the verdure and the yellow waters of the Sound; and this same atmospheric magic must enable the Mississippians to study our array of masts and smoke funnels; all the same we are twenty miles asunder.

We are in the rainy season now, and the mornings are chilly. I have a chance to know this, for we get up at sunrise. Then the reveille beats; the men turn out under arms; the three commissioned officers look on while the first sergeant calls the roll; the muskets are stacked and the men break ranks. At half past six we breakfast; from seven to eight there is company drill; from half past nine to half past ten, more company drill; at twelve, dinner, which means soup and hardtack; from four to six, battalion drill; at half past six, hardtack, pork and coffee; at nine, another roll call; at a quarter past nine, lights out. It is a healthy, monotonous, stupid life, and makes one long to go somewhere, even at the risk of being shot.

… Man is a brave animal, at least when danger is distant. Nine out of ten of our invalids got well as soon as they heard that we were to fight. None of my company wanted to stay behind, although five years on the sick list and one of them could scarcely hobble. As for myself, my only fear was lest my men should disgrace me and the regiment by running away; and I loaded my revolver with the grim intention of shooting the first dastard who should start for the rear. Of course, if ever bullets begin to whistle about me, I may set the example of poltroonery. That suspicion really alarms me more than anything else. “Let not him that putteth on his armor boast himself.” …

You would perhaps like a sketch of General Butler.9 Three of us Twelfth officers called upon him apropos of rations, and in my character of novelist I made a study of him. He is not the grossly fat and altogether ugly man who is presented in the illustrated weeklies. He is stoutish but not clumsily so; he squints badly, but his eyes are very clear and bright; his complexion is fair, smooth and delicately flushed; his teeth are white and his smile is ingratiating. You need not understand that he is pretty; only that he is better looking than his published portraits.

He treated us very courteously and entered into the merits of our affair at length, stating the pros and cons from the army regulations like a judge delivering a charge, and smiling from time to time after the mechanical fashion of Edward Everett, as if he meant to make things pleasant to us and also to show his handsome teeth.10 On the whole he seemed less like a major general than like a politician who was coaxing for votes. The result of the interview was that we got the desired order and departed with a sense of having them flattered.

Yesterday I called on General Phelps, the chief of our brigade.11 He is a swarthy, grizzled six-footer, who looks all the more giant-like because of a loose build and a shambling carriage, and says unexpected things in a slow, solemn humoristic way.

“Come in, Captain; what’s the news?” he drawled, rather satirically as I thought; for how can a captain tell a general anything?

When I replied that I had heard nothing but vague and absurd reports about possible movements, he smiled as if approving my incredulity, or my reticence, and said, “Sit down, Captain; what do you want?”

I explained that I merely wanted some blanks for my property returns from the brigade quartermaster; but he kept me nearly half an hour, talking much about drill and discipline and more about the South. He hates the Rebels bitterly, not so much because they are rebellious as because they are slaveholders, for he is a fervid abolitionist. He would not hearken with patience to the faint praise which I accorded them for their audacity and courage. His face flushed, and he replied in an angry snarl, “What have they done? They brag enormously and perform next to nothing. Their deeds fall so far below their words that they are nothing less than ridiculous.” …

Well, the forts have been captured, and New Orleans also…. I shall probably astonish you when I say that we did not find the bombardment magnificent nor even continuously interesting. It was too distant from us to startle the senses and too protracted to hold our attention. We could hear a continuous uproar of distant artillery; we could see clouds of smoke curling up from behind the leafage which fringed the river; and on the first day, when we were near the scene of action, we could see vessels lying along the low banks. Also, if we climbed up to the crosstrees, the forts were visible beyond a forested bend. Then we were ordered to the head of the passes, seven miles below; and there we lay for a week, gradually losing our interest in the combat.

We smoked and read novels; we yawned often and slept a great deal; in short, we behaved as people do in the tediums of peace; anything to kill time. Once or twice a day we got a rumor from above that the bombing was doing wonders, or that it was doing nothing at all. Now and then a blazing fireship floated by us, lighting red the broad, swift, sublime river, and glowing away southward….

We had a charming sail from Fort Jackson to New Orleans through scenery which surpasses the Connecticut River valley and is not inferior to that of the Hudson, though quite different in character.

It is a continuous flat, generally below the level of the Mississippi, but richly beautiful and full of variety. The windings of the mighty river, the endless cypress forests in the background, the vast fields of cane and corn, the abundant magnolias and orange groves and bananas, the plantation houses showing white through dark-green foliage furnished an uninterrupted succession of lovely pictures. Of course the verdure was a fascinating novelty to men who came last from the white sands of Ship Island, and previously from the snows of New England.

Apparently this paradise had been nearly deserted by its inhabitants. Between Fort Jackson and Chalmette, a few miles below New Orleans, we saw hardly fifty white people on the banks, and the houses had the look of having been closed and abandoned. Even the Negroes were far from being as numerous as we had expected. None of the whites signalled to us, or took any other notice of us, or seemed to see us. One elderly man, driving northward with a rockaway full of women, kept along with us for a quarter of a mile or so, without once turning his white-bearded face toward us.

The blacks, as might be expected, were more communicative and more friendly. They gathered to stare to us, and when there were no whites near, they gave enthusiastic evidence of good will, dancing at us, waving hats or branches and shouting welcome. One old mauma, who spoke English and had perhaps once been “sold down de ribber,” capered vigorously on the levee, screaming, “Bress de Lawd! I knows dat ar flag. I knew it would come. Praise de Lawd!”

Perhaps some of the planters had fled the region in fear of a slave insurrection; but, as we had learned at Fort Jackson, they had another reason for seeking a place of safety. The fleet had come up the river like an angel of destruction, hurling shells and broadsides into thickets which sheltered ambuscades, and knocking to pieces dwellings occupied by guerrillas. Seventeen miles below New Orleans it pitched into Fort Leon, and sent the garrison flying across the flats to the cypress forest. Then the town surrendered, and with it all the fortifications in the vicinity, while the Rebel troops scurried up the river….

… The poverty of the once flourishing city of New Orleans is astonishing. I have seen nothing like its desolation since I quitted the deserted streets of Venice, Ferrara and Pisa. Almost the only people visible are shabby roughs and ragged beggars. Many poor Irish and Germans hang about our regiments begging for the refuse of our rations. The town is fairly and squarely on the point of starvation. No one denies now that our blockade has been effective; it kept out everything, even to the yellow fever. General Butler has commenced distributions of food; and it is possible that industry will recover within a few weeks from the fright of the threatened bombardment; but it will be years before it quite recovers from all the effects of this stupid rebellion.

Unless work is soon found for these people, I do not see how famine can be averted. Flour ranges from twenty-three to thirty dollars a barrel; Irish potatoes, eight dollars a bushel; sweet potatoes, undiscoverable. Mess beef, which the quartermaster holds at thirteen dollars a barrel, sells in the city at thirty. The country people charge us ten cents a quart for milk and seventy-five cents a dozen for eggs. A common broom, worth a quarter of a dollar at the North, fetches here a quarter of an eagle; a tin teapot, worth sixteen cents in Connecticut, costs seventy-five cents in Louisiana. Apparently, if the South should be corked up and left to itself, it would very soon turn savage and go naked. Already it is verging on the barefooted stage; common soldiers’ shoes sell for eight dollars; cavalry half-boots for twenty and thirty.

Of course these prices represent the depreciation of Confederate money as well as the scarcity of merchandise. Specie there was none before we arrived; nothing but shinplasters of fifty contemptible descriptions; a worse state of things than in bankrupt Austria. Louisiana small change consists of five-cent tickets for omnibuses, barrooms and shaving shops. Shortly after our landing my first sergeant bought some tobacco for the company and paid in gold and silver. The shopkeeper, a German woman, caught up a quarter of a dollar, kissed the eagle on it and said, “That’s the bird for me. Why didn’t you men come long ago?”

Negroes have depreciated as much as any other Southern circulating medium. They straggle into camp daily, more than we know what to do with. I have one named Charley Weeks, a bright and well-mannered mulatto, evidently a pet household servant, and lately chattel to one General Thompson of the departed Rebel army.12 He has a trunk and two suits of broadcloth, besides his workaday clothes. I have established him in my cooking tent and promised him my sublime protection, which is more effective here now than it would have been three weeks ago.

… I begin to despair of finding a chance to fight unless there is another war after this one.

Singular as it may seem, this is a disappointment. Nearly every officer and the majority of the men would prefer to go up the river, taking the certainty of hard fare and hard times generally, with a fair likelihood of being killed or wounded, rather than stay here drilling and guard mounting in peace. When the long roll beat for the Seventh Vermont to start forward, they hurrahed for ten minutes while we sulked over their luck and their exultation, not even giving them a cheer as they marched by us to embark. Meanwhile we sniff at the Thirteenth Connecticut as a dandy corps which has never lived out of doors and is only fit to stand guard around General Butler. We believe that we could whip it in a fight, and we know that we could beat it in battalion drill. And so on, through a series of grumblings and snarlings, all illustrative of human nature….

The Twelfth also has contrabands, fully sixty in number, some of them nurses and laborers at the hospital, others servants to officers, the remainder company cooks. Two of them carry my written protections in their pockets. Who said John Brown was dead? There are six hundred thousand John Browns now in the South. The old enthusiast is terribly avenged. The rotten post of slavery is getting a rousing shake.

The officer of the guard tells me that outside of his picket there is a camp, or rather bivouac, of one hundred and fifty Negroes, lately arrived from the other bank of the river. Their owner (a thousand-hogshead man) got into a rage about something, perhaps their insubordination, ordered them off the plantation and bade them go to the devil. Also there is a great floating population of blacks; men and women and pickaninnies streaming daily into the camp and sticking there until they are expelled as “unemployed persons”; a burden to the soul of our brigade provost marshal and a subject of intense commiseration to our general….

… There was a little fight up the river a few days ago. A party of guerillas ambuscaded a company of Vermonters, killed or wounded thirteen men, and scampered off. This is the only skirmish which has occurred within forty miles of here since New Orleans surrendered. I had no idea until lately what a Quakerly business war could be. You need not fear but what the Twelfth will have a peaceful and inglorious campaign. Beauregard would be an idiot to venture into this narrow belt between the river and the swamps to attack our strong line of fieldworks under a flanking fire from gunboats and frigates. This is the only country I ever saw except Holland where the water commands the land. A ship in the river looks to us as if it were on a hill….

… As to the Negroes, they are all on our side, although thus far they are mainly a burden. In spite of indirect discouragements they are continually quitting the plantations and swarming to us for protection and support. Lieutenant Potter, our brigade provost marshal, has on his roll seven hundred of them, all living in or about the camp and drawing rations. Potter wishes they were on the coast of Guinea, and sulkily asks General Phelps what he shall do with them.

“I don’t know,” squalls the brigadier, as much bothered by the “inevitable nigger” as if he were not an abolitionist. If he had his own way, doubtless, he would raise black battalions; indeed, he has already asked one of our captains if he would be willing to command a colored regiment; whereupon the captain replied that he wouldn’t….

We wish we were on the Potomac or the Rappahannock. Why does not the president send out some of the new regiments to guard subjugated Louisiana, and so set us drilled fellows free for active service? One does not want to go into the army merely to return home without seeing a battle. Besides, there are no promotions; nobody is killed and nobody gets scared into resigning; there is not a chance for a captain to become a field officer….

The truth is (although you must not publish it) that the division has run down terribly in numbers. There is a constant drain on troops in the field, much heavier than a civilian would suppose. Something like one fifth of the men who enlist are not tough enough nor brave enough to be soldiers. A regiment reaches its station a thousand strong; but in six months it can only muster six or seven hundred men for marching and fighting duty; the rest have vanished in various ways. Some have died of hardship, or disease, or nostalgia; as many more have been discharged for physical disability; others are absent sick, or have got furloughs by shamming sickness; others are on special duty as bakers, hospital nurses, wagoners, quartermasters’ drudges, etc.; a few are working out sentences of court-martial. Thus your division of fifteen thousand men has dropped to ten thousand or perhaps eight thousand effectives. The companies have each lost one if not two of their original three officers. There you have our history.

Meantime the government is raising new organizations, instead of filling up the old ones; and to make matters as bad as possible it is putting its green regiments into the hands of green officers. To be effective, troops must have drill and discipline; and the only way to give them these qualities is to give them commanders who know their business; why shouldn’t even a politician understand that?

Our whole system of raising an army is wrong; we ought to raise it by draft, by conscription. Then our governors, instead of appointing officers who can merely electioneer, could appoint such as have learned how to command. The South has resorted to conscription, and it will beat us if we don’t follow suit. With a far inferior population it can levy soldiers faster than we can, and it can put them under experienced colonels and captains.

What is it but drafting which has enabled it of late to resume the offensive? Here is Breckinridge13 invading Louisiana; losing the battlefield, to be sure, but still awing us out of Baton Rouge; and only a little while ago we held the river up to Vicksburg. Where did Jefferson Davis get the materials for these new armies? The whole secret of their numbers, and of their energy and effectiveness too, is conscription.

But if I keep on you will know as much of war as I do, which would be very improper in a woman and might lead to more rebellion.

This is the rainy season here, but by no means a cool season. I cannot give you the temperature, for there is not a thermometer in the brigade; but in scorching and sweating a man’s strength away it beats anything that I ever before experienced. Sitting in my tent, with the sides looped up all around, I am drenched with perspiration. I come in from inspection (which means standing half an hour in the sun) with coat and trousers almost dripping wet, and my soaked sash stained with the blue of my uniform. There is no letup, no relenting, to the heat. Morning after morning the same brazen sun inflames the air till we go about with mouths open like suffering dogs. Toward noon clouds appear, gusts of wind struggle to overset our tents, and sheets of rain turn the camp into a marsh, but bring no permanent coolness.

The night air is as heavy and dank as that of a swamp, and at daybreak the rotten odor of the earth is sickening. It is a land moreover of vermin, at least in this season. The evening resounds with mosquitoes; a tent hums with them like a beehive, audible rods away; as Lieutenant Potter says, they sing like canary birds. When I slip under my mosquito bar they prowl and yell around me with the ferocity of panthers.

Tiny millers and soft green insects get in my eyes, stick to my perspiring face, and perish by scores in the flame of my candle. Various kinds of brilliant bugs drop on my paper, where they are slain and devoured by gangs of large red ants. These ants rummage my whole habitation for rations, crawl inside my clothing and under my blanket at night, and try to eat me alive. I have seen many large “lightning bugs,” such as the Cuban ladies sometimes wear in their hair. Also there are black grasshoppers two or three inches in length, with red and yellow trimmings to their jackets, the most dandified fellows of their species that I know of….

Last evening I thought that Breckinridge had come, and that the Twelfth was about to fight its first battle. About nine o’clock scattering musket shots broke out on the picket line, running along the front from the river to the cypress swamp. Then, before I could buckle on sword and revolver, there was a yell from the sergeants of “Fall in!” followed by the long roll of all the regiments roaring sullenly through the damp night.

The rain had poured nearly all day, and the camp was a slop of mud and puddles. My men splashed through the sludge and halted on the little company parade, jabbering, reeling and scuffling. I saw at once what was the matter: payday had worked its usual mischief: one third of them were as drunk as pipers. In my rage at their condition I forgot all about the enemy. I pushed and flung them into their places, and called them sots, and used other bad language….

To comprehend this drunkenness you must understand that many of my men are city toughs, in part Irish; also that they are desperate with malaria, with the monotony of their life, and with incessant discomforts; finally, that intoxication in itself is not a military offence and not punishable. If you could look into our tents you would not wonder that consolation is sought for in whiskey. The never-ceasing rain streams at will through numerous rents and holes in the mouldy, rotten canvas. Nearly every night half the men are wet through while asleep unless they wake up, stack their clothing in the darkness, and sit on it with their rubber blankets over their heads, something not easy to do when they are so crowded that they can hardly move.

It must be added in fairness that intoxication is not confined to the soldiers. The officers are nearly as miserable, and are tempted to seek the same consolation. Lately a lieutenant reeled into my tent, dropped heavily on bed, stared at me for a minute as if to locate me, and said in a thick voice, “Capm, everybody’s drunk today. Capm, the brigade’s drunk.”

… Yesterday’s mail brought me a letter from the wife of one of my private soldiers. She had not heard from her husband for a month, and she wanted to know if he was in trouble or was dead. She had received nothing from him since he enlisted but one remittance of nine dollars. A mortgage on her house had been foreclosed; and as her husband is not a Connecticut man, the authorities of her township will not allow her the “family bounty”; hence she and her children are likely to be homeless as well as penniless.

I fear that she will get little aid from her husband. He is a mild, weak young fellow, easily led away by comrades, low-spirited under the slightest illness, given to cosseting himself with sutler’s trash, and given also to seeking courage in whiskey. Thirteen dollars a month can easily be spent in these follies.

The letter is nicely written and correctly spelled; moreover, it is well phrased and loving and touching. It is full of her husband; full of adoration for the poor creature and of prayers for his unimportant safety; pious terrors lest he may have been drawn into evil ways; prayers to me that I will not conceal from her the possible worst; then declarations that the feeble lout is the best of husbands; it is no fault of his—no fault of Henry’s—that his family suffers.

In short, here are four pages of pathos which make me want to call in Henry and kick him for not deserving them. Apparently a fairly educated and quite-worthy girl has married a good-looking youth of inferior nature and breeding who has not the energy to toil effectively for her, nor the affection to endure privations for her sake. I shall give the letter to him with a few words of earnest, epauletted counsel. It may stop him from drinking himself into the gutter twice after every payday, and from sickening himself with bushels of abominable gingerbread and shameless pie.

Do you fancy the idea of my applying for the colonelcy of a colored regiment? Important people here advise it and promise to help me with recommendations. It would be a comfortable position, I suppose; but there are some obvious serious disadvantages. The colored troops will probably be kept near here and used to garrison unhealthy positions; they will be called on for fatigue duty, such as making roads, building bridges and draining marshes; they will be seldom put into battle, and will afford small chances of distinction.

Since writing the above I have talked on the subject with Colonel Deming, who is acting mayor of New Orleans and well informed concerning affairs at headquarters. I had decided to apply for a black regiment, and I wrote to him for an introduction to General Butler. Thereupon he sent for me, treated me to a fine dinner and gave me his views.

“I advise you,” said he, “not to make your proposed application, for fear it might be successful.”

Then he went into details concerning the character of the officers who would be associated with me, and the nature of the service that will be assigned to the Negro troops, which details I do not feel free to repeat. In short, he counselled me so urgently against the step that I have given it up and decided to fight my way on in the Twelfth, if it is ever to have any fighting.

I must tell you of an adventure of mine with one of the heroines of secession. On my way down to the city in the crowded, dirty cars, I saw behind me, standing, a lady in half-mourning, a pallid and meagre young woman, with compressed thin lips, sharp grey eyes and a waspish expression. Much doubting whether my civility would be well received, I rose and offered her my seat. She would not look at me; she just conceded me a quick shake of the head and a petulent shrug of the shoulders; then, pinching her pale lips, she stood glaring straight before her.

After waiting her pleasure a moment I resumed my seat. Presently a rather pretty lady opposite me (a young mother with kindly eyes and a cultured expression) took her little girl into her lap and beckoned the scowling heroine to the vacant place. She accepted it with lavish thanks, adding in a loud, ostentatious tone, “I wasn’t going to take a seat from a Yankee. These cars used to be a fit place for ladies. Now niggers and Yankees crowd decent people out.”

The lady with the kindly eyes threw me an apologetic glance which seemed to say, “I hope you did not hear.” There ended the comedy; or was it a tragedy? …

I have received your comments on our Liliputian battle at Labadieville. You must understand that I took post in the front rank during the charge for a good reason. As my men had never been under fire before, I was afraid they might get startled and disorderd, and I wanted to set them an example in facing danger. I can trust them now and shall hereafter march in rear of the company, where a captain should be according to the drill book.

I have discovered why officers are in general braver than soldiers. The soldier is responsible for himself alone, and so is apt to think of himself alone. The officer is responsible for his company, and so partially forgets his own peril. His whole soul is occupied with the task of keeping his ranks in order, and it is only now and then that he takes serious note of the bullets and shells. It would demand a good deal of courage, I think, to be a mere looker-on in a battle.

An officer of the —th gave me an amusing account of the chaplain of his regiment; sitting his horse calmly in rear of the charging, yelling line and peering after it through his specs with an expression of enlightened curiosity; now glancing at the rolls of smoke which marked the Rebels’ position and now at the tufts of dust thrown up by their shot; the whole man as bland and content as if he were in a prayer meeting. He is a terrible forager, this valiant young son of the prophets. He makes frequent pilgrimages after provisions for his flock and helps personally towards devouring the substance of the enemy. Some days ago he presented himself at regimental headquarters and said, “Colonel, the health of this battalion requires sweet potatoes, and I should like permission to take up a contribution. By the way, it is Sunday, I believe. If I get back early enough, I shall preach this afternoon.”

Off he went with a couple of soldiers, impressed a plough and a pair of mules at a plantation, and returned with a load of vegetables.

But we have nearly worn out the foraging business. The land for miles is as bare of pigs as if a legion of devils had run away with them all. Meantime I am nourished at a moderate cost in an honest fashion. One of my men has been detailed as guard over two large plantations, his duty being to drive off plunderers and to make the Negroes get in the sugar crop. The owners are humbly thankful for his protection; they have given him a pony, a hogshead of sugar and a barrel of syrup; and they allow him to bring me poultry at fair prices and vegetables for nothing.

Having been paid off lately, I am able to purchase, and we live well. Occasionally there is a hiatus; for instance, our sweet potatoes and turnips and cabbages arrived late this morning; consequently we had nothing for dinner but bread and roast turkey. But “accidents will happen in the best regulated families.”

Excuse this woefully soiled paper. It is as clean as it can be after having been treasured for a week in the dirty pocket of a very dirty captain. You can hardly imagine how unclean and ragged our regiment is, officers as well as soldiers. On all sides I can see great patches of bare skin showing through tattered shirts and trousers. I have but one suit, and so cannot wash it. My pantaloons will almost stand alone, so stiff are they with a dried mixture of dust, mud, showers and perspiration.

I look forward with longing unutterable to the day when I shall be able to substitute decent clothing for the whole foul encumbrance. I am far less out of humor with my wretched food which has consisted for weeks of little else than fried or boiled doughballs with an occasional seasoning of blackberries or of a minute slice of rusty bacon. It is rather surprising that under such circumstances we of the Twelfth are fairly healthy and show few men on the sick list compared with some other regiments. In killed and wounded we have been lucky, losing but little over a hundred out of about four hundred, while the Eighth New Hampshire and Fourth Wisconsin have been nearly exterminated….

… The heat is tremendous. Flies are thicker than in Egypt, and mosquitoes thicker than in Guilford. But it is astonishing how healthy and contented our bronzed veterans are. They build themselves hovels of rails and boards, bake under them like potatoes in hot ashes, and grumble at nothing but the lack of tobacco. A soldier is not a hero in fighting alone; his patience under hardship, privation and sickness is equally heroic; sometimes I feel disposed to put him on a level with the martyrs….

… We forage like the locusts of Revelation. The Western men plunder worse than our fellows. It is pitiful to see how quickly a herd of noble cattle will be slaughtered. Our Negro servants bring in pigs, sheep and fowls, whether we bid it or forbid it. Of course, after the creatures are dead and cooked, we eat them to save them, for wasting food is prejudicial to military discipline.

It is curious how honest these looting darkeys are toward their employers; I never knew one of them to steal anything from a Union officer or soldier. They say that they used to feel free to rob their old masters, but it would be wrong to rob a man who hires them and pays them wages….

I wish you could understand how difficult I find it to write even one letter. Since mailing my last I have had no baggage but my overcoat and rubber blanket. This half-sheet of foolscap was begged from a brother captain who begged the whole sheet from the adjutant general of our brigade. The ink was loaned me by another officer, and I hope somebody else will give me an envelope. The pen, thank Providence, is mine, and I still possess one postage stamp….

We had lain for ten days within hearing of the bombardment of Fort Jackson, within sight of the bursting shells and of the smoke of that great torment, but still we had not as a regiment been under fire. We were the first troops to reach conquered New Orleans; but we had never yet heard the whistling of balls, excepting in a trifling skirmish on Pearl River, where five of our companied received a harmless volley from forty or fifty invisible guerrillas. About all that we knew of was the routine of drill and guard duty, and the false night alarms with which our brigadier used to try us and season us. No, I am mistaken: we did know what it was to suffer; to wilt under a Southern sun, and be daubed with Louisiana mud; to be sick by hundreds and die by scores. But now we were to quit garrison duty behind the great earth-works of Camp Parapet, and go into offensive operations. Lieutenant Godfrey Weitzel of the Engineers, the chief military adviser of General Butler, had lately been created Brigadier-General, and the extenuated forces of the department were exhausted to furnish him with a brigade suitable to the execution of the plans which he proposed.14

Weitzel did not want the Twelfth Connecticut. It was generally believed that the regiments which garrisoned Camp Parapet were not only sickly but broken in spirit and undisciplined. Sickly I have admitted that we were; but not broken in spirit, except so far as that life, from constant misery, had come to seem hardly desirable, and death, by constant presence, had lost its terrors; while, as to the third charge, I can neither broadly admit nor squarely deny it….

On the 24th of October, 1862, [the brigade] embarked on some small river steamers, and, convoyed by three gun-boats, sailed one hundred miles up the Mississippi, landing the following day near the once flourishing little town of Donelsonville. Donelsonville is on the right or western bank, astride of the Bayou Lafourche, which is one of the numerous outlets of the Mississippi, and carries off a considerable body of water through the rich district of Lafourche Interieur. The place was in ruins, shattered by shells and half burned—a punishment which had fallen upon it for firing on Farragut’s gun-boats.15 Our regiment slept on the floor of a church, and I ate my supper off a tombstone in the cemetery. At six in the morning, leaving the First Louisians to hold Donelsonville, we commenced our march, following the bayou in a westerly and then in a southerly direction, one regiment of infantry and one company of cavalry on the right bank, the remainder of the brigade on the left bank. Communication was secured by two gigantic Mississippi flat-boats, easily convertible into a pontoon-bridge, which were towed down the current by mules and contrabands.

This was the first night that our regiment passed out of doors. I thought I never should get to sleep. I had a bed of cornstalks, but I believed I was roughing it. It was the dreadful exposure to the night air which worried me, and not the proximity of hostile balls and bayonets. And when I was aroused at five in the morning to continue the march, I actually felt more fearful of being broken down by want of proper rest than of being shot in the approaching engagement. How mistaken our mothers were when they warned us against exposure to night air, and sleeping in damp clothing, and going with wet feet! Judging from a two-years’ experience of almost constant field-service, I aver that these things are wholesome and restorative. It does not require a strong constitution to stand them; it is sleeping inside of walls which ought properly to be called exposure, and which demands a vigorous vitality; and it is the crowning triumph of civilization that it enables humanity to do this without extermination. I have a screed to deliver some day on this subject to a misguided and housepoisoned public….

The troops marched as loosely as usual, in the road, on the levee, and all over the lots, taking advantage of every possible cut-off, and presenting an extraordinary contrast to the rank-and-file regularity of movement which the same regiments were brought to after six or eight months more of field duties. We passed pretty, flourishing plantations, and endless flats of waving green sugarcane. The roads were vacant of vehicles; not an individual of the dominant white race showed his face; but crowds of negroes rushed out with the tumultuous simple acclamations of joy. It was “God bless you, massas!—Oh, de Lord’s name be praised!—We knowed you’d come!—I’se a gwine ’long with you.” And go with us they did by hundreds, ready to do anything for us, and submitting uncomplainingly to the trickeries and robberies which were practiced upon them by the jokers and scape-graces of the brigade. Looking ahead down the longer stretches of the winding bayou, we could occasionally see the parti-colored flags of the signal corps waving from some conspicuous angle of the levee, as they sent back in silent messages the discoveries of the advanced scouts. As on the day previous, we came across a freshly-deserted bivouac of the rebels, and we learned from the negroes that they numbered about five hundred, chiefly cavalry or mounted infantry. I, for one, expected no engagement, not knowing that these troopers were hastening to join a force of about two thousand infantry and artillery which General Mouton had collected at Thibodeaux, the capital of the Lafourche district.16 Moreover our regiment formed the rear of the column, and I, as officer of the day, marched with the rear-guard of the regiment, so that I seemed to be far away from all chances of battle.

Then came a story that the fighting had been going on in front for more than an hour, and that the Thirteenth Connecticut had already lost seventy men; which, by-the-way, was only one of the numerous false rumors that fly broadcast like grape-shot through every combat; the losses being trifling up to this time, and the Thirteenth not having yet been engaged….

When we received orders to move forward I obtained permission of the colonel to quit the rear-guard and take command of my company. With drums beating, fifes screaming, and banners floating, we hurried on, listening to the slow dropping of artillery two miles distant. I was anxious, but so far only for my men, not knowing how they would behave in this their first battle. I commenced a rough and ready joking with them, not because I was gay, but because I wanted them to be gay. I have forgotten what I said; it was poor, coarse fun enough probably; but it answered the purpose.

Well, the light-hearted, reckless, yet steady countenances of the company, and of the whole regiment, was all that one could desire. We found the pontoon-bridge in position, and the two howitzers which protected it firing slowly, while an unseen rebel battery answered it with equal deliberation. Here we first came under fire, and here I first saw a wounded man. In a country carriage, upheld by two negroes, was some sufferer, his knee crushed by a shot, his torn trowsers soaked with a dirty crimson, his face a ghastly yellow, and his eyes looking the agony of death. I did not want my men to see the dismaying spectacle, and called their attention to something, I have forgetten what, which was passing on the other side of the bayou. As we rushed down the inner slope of the levee an amazingly loud, harsh scream passed over us, followed by a sharp explosion and a splashing in the water. I was not alarmed, but rather relieved and gratified. If they can’t aim better than that, I simply thought they are welcome to fire all day. Then came another shell, striking close to the crowded bridge and spattering the men, but without deterring the thirsty ones from stopping to fill their canteens. It was wonderfully fine practice, considering that they were aiming at us from behind the levee, half a mile down the stream, where the fellows who worked the guns could not see us. I remember that my chief anxiety while crossing was lest I should wet my feet in the sloppy bottom of the flat-boat. The terror of battle is not, I think, an abiding impression, but one that comes and goes like throbs of pain; and this is especially the case with veteran soldiers, who have learned to know when there is danger and when there is not; the moment an instantaneous peril has passed they are as cool as if it had never approached. But on the present occasion, I repeat, I was not oppressed by any feeling which could be called even alarm. I was buoyed up by the physical excitement of rapid movement, by my anxiety that my company should do well, and by my ignorance of the profounder, the really tremendous horrors into which battle may develop. A regiment of well-drilled greenhorns, if neatly brought into action, can charge as brilliantly as veterans….

As we approached the edge of the wood nearest the enemy they caught sight of us, and a shell screamed over our heads, passing through the lower branches and sending down a shower of leaves. Nearly the whole regiment bowed low and gracefully but without halting or breaking. Stepping to the front, I turned around and laughed at my men saying, “I beg your pardon for not bowing when you did; the truth is, I did not think of it until it was too late.” This was pure bravado, not characteristic of me, I hope, but suggested by the fear that my new soldiers were getting frightened, and intended to restore their spirits. Poor as the joke was it actually made them laugh, so slight was their anxiety, if any.

The shells came fast now, a majority of them screeching over the colors, at which they were evidently aimed. Not only were the four guns directly in front of us booming rapidly, but Sim’s battery, half a mile down the bayou, and on the other side, was pitching his iron about us at a venture. Meantime our own two howitzers, the only ones as yet brought into action by Weitzel, had ceased firing, so as not to interfere with our advance. I remember that this damped my spirits at the time, although it was of course absolutely necessary. Each shot came lower than the last, and I thought calmly, they will hit something soon. I did not attempt to dodge. I reflected that a missile would hit me about the same time that I should hear it. I believed that the eyes of all my soldiers were upon me (whereas they were probably looking only for the enemy); and so, for reason’s sake and example’s sake, I kept my head steadfast. It cost me no great effort. I had no nervous inclination to duck, no involuntary twitching or trembling; I was not aware of any painful quickening of the pulse; in short, I was not frightened. I thought to myself, it is very possible that they will hit me, but I hope not, and I think not. It seemed to me the most natural thing in the world that others should be killed, and that I should not. I have suffered more in every engagement since than I did in this first trial. It is a frequent, it is the usual experience….

We were just entering a large open field, dotted by a few trees and thornbushes, with a swamp forest on the right and the levee of the bayou on the left, when the rebels gave us their musketry. It was not a volley, but a file fire—it was a long rattle like that which a boy makes in running with a stick along a picket-fence, only vastly louder; and at the same time the sharp, quick whit whit of bullets chippered close to our ears. In the field little puffs of dust jumped up here and there; on the other side of it a long, low blue roll of smoke curled upward; to the right of it the gray smoke of the artillery arose in a thin cloud; but no other vestige of an enemy was visible.

About this time the First Lieutenant of Company D was surprised at seeing two of his men fall down and roll over each other. To his mind they seemed to be struggling which should get undermost, and thus find shelter from the bullets. “Get up! get into the ranks!” he commanded, hitting the uppermost with the flat of his sabre. One of them silently pointed to a bloody hole in his trowsers and lay quiet; the other rose with a mazed air, looked about for his rifle, picked it up and ran after the company. A bullet had struck this man’s piece, dashed it against him with such force as to knock him down, glanced, and passed through the thigh of his comrade.

The First Lieutenant of Company G had his hand on the shoulder of a laggard, pushing him forward into the ranks, when a fragment of a shell struck the man in the breast, passing downward through his body and killing him instantly. Private Judson of Company C flung up both hands with a loud scream and dropped dead with a ball in his heart. A shot through the foot disabled the left corporal of my company. A bullet struck the rifle of the man next to me in the rear rank, knocking it off his shoulder, end over end, several feet distant. Picking it up he showed me the now useless lock, and asked me what he should do. “Fetch it along,” I said, “you may have a chance to use the bayonet; we shall be up there presently.” Bringing it to a right-shoulder-shift he fell into his place and made the charge in that manner. On the right of me a sharp crash, as of dry bones broken by a hatchet, drew my attention, and, looking that way, I saw Edwards, one of the color-bearers, fall slowly backward, raising one hand to his mouth as the blood spurted from it; an “Oh!” of pain or alarm burst from his lips, and in his eyes there was a stare of woeful amazement.

I had expected that such sights as this would be most depressing and terrible. It was not so; it was not even painful; it hardly seemed unnatural; it only produced a feeling of surprise. Kelley of the color guard, one of our Louisiana recruits, seized the Stars and Stripes from the fallen man’s hand and bore them onward, calmly chewing his tobacco….

The men fell into line again, and the dropping file fire had commenced in our ranks when I and every one near me heard distinctly a loud order to lie down. Down we went, all the more smartly, I think, because at that instant a shell flew between the colors with a deafening, hoarse screech as if the rebels had fired a brace of mad catamounts at us. I remember that I laughed at the nervous haste of my plunge, and that I saw one of my men laughing also as he went down, probably for similar reason. In my boyhood I have ducked the same way, and with very much the same laugh, in escaping from a particularly swift snow-ball.

“Forward!” we heard the Colonel shout; and springing up we advanced. It was our last stop. The men were excited, but not frightened. On they went, file-firing, straight toward the enemy, in the teeth of cannon and musketry. There was a heavy pressure from right to left toward the colors; some of my small men were crowded out of their places; we were three ranks deep instead of two. As little Sweeny dodged along the rear, trying to find a crack in the living, advancing wall to poke his gun through, one of my officers twice collared him and dragged him back to his place, saying, “What the — and — are you doing on the right of the company?”

“Lieutenant,” was the ready answer, “I am up here purtectin’ thim colors.”

The swearing mania was irrepressible; nothing but oaths could express our feelings. I was not a profane man; I never swore at one of my company before that day; but at that moment I had a gift. In the rage of the charge, in the red presence of slaughter, it seemed as if every possible extremity of mere language was excusable, provided it would aid in gaining victory. A serious friend has asked me since if I did not think of eternity. Not once. I was anxious for nothing but to keep a steady line and to reach the enemy’s position. I did not, as I previously supposed I should, urge my soldiers to fight desperately and fire rapidly. They were fighting well enough and firing fast enough. Nearly all that I said might be summed up as repetitions of the two orders, “Close up” and “Guide right.” I even swore at one of the color corporals for being out of line, although the man had simply dropped back a pace in the process of loading….

The field, I have said, was a quarter of a mile long. We had passed over onehalf of it before I saw a single man of the hostile force; and their cannon I did not see at all, so well were they masked by shrubbery, although I could perceive the puffs of smoke which they gave out when discharged. Numbers of men in the regiment never laid eyes on a rebel during the whole action. The first troops that we caught sight of were probably the Lafourche militia, Mouton’s reserve, which came down the cross-road on a run to reinforce the threatened position. As soon as they got in our front they commenced firing irregularly, without halting or forming, then broke suddenly in a panic, rushing into the thickets in their rear, and disappearing in a most rapid, harmless manner. This I did not see, for it happened opposite our right wing, and my eyes were set straight forward. But when we had got half across the field I became aware that the hostile battery had ceased firing; and immediately thereafter I perceived a crowd of men spring up from behind the fence in front of us, plunge across the road, and sweep into the forest, seeming to be actually jumping over each other in their haste, and looking, in their gray uniforms, like an immense flock of sheep swarming over a fence. At this sight our regiment raised a spontaneous yell of triumph, and quickened, if possible, the fury of its fire….

One of the first men whom I beheld in the morning was Edwards, the color-bearer, whom I had seen fall with what I supposed to be a mortal wound, and who now presented himself to claim his colors, having understood that we were to have a second battle. The ball had actually passed through his head, entering the mouth, and coming out behind the left jaw. He simply complained that his mouth was very sore, and that he could eat nothing but soup. He was ordered back to hospital, being evidently too severely hit to do duty; and in fact he had a long illness, the fever of the hurt terminating in typhus. One of the most noticeable things in war is the heroism of the wounded.

Notwithstanding the great length at which I have described the combat of Labadieville, our regimental loss was but two killed and fourteen wounded. Its smallness was owing in part to the rapidity with which we advanced, and the consequent brevity of our exposure to fire, only an hour and twenty minutes elapsing from the time the first shell passed over us to the moment of reaching the fence. It did not seem, by-the-way, fifteen minutes. The entire loss of the brigade was less than ninety killed and wounded, of which about one-half fell to the share of the Eighth New Hampshire….

Of all the combats that I have seen this one was the most scientific, orderly, comprehensible, and artistically satisfactory. I will venture one other military reflection. I think the success of our regiment in charging veterans in a strong position was owing very much to the file-fire which we kept up while advancing. In the first place, it supported the spirits of our men, who believed that they were doing as much damage as they received, and felt that they ought to be able to bear the trial as long as the enemy. In the second place, it killed the musketry of the rebels, who, unfortunately for their morale, I think, had for shelter a deep plantation ditch, which served them the purpose of a rifle-pit. Now a human being who has a cover in battle hates to put his head outside of it. As a proof that we actually did overwhelm and derange the hostile musketry, I may adduce the fact that we had only six men hit by bullets. The rebels lost very few, to be sure; but the fence above their heads was so tattered by our shot as to be a curiosity; and the prisoners said that, what with the whizzing of Miniés and the flying of cypress splinters, the ditch was a most unpleasant position. I believe the manoeuvre of file-firing while advancing in battalion line to be quite a novelty. Notwithstanding frequent inquiries on the subject, I never yet heard of any other regiment having practiced it. An attacking line generally halts from time to time and delivers volleys, or advances at a right-shoulder shift, taking what the enemy sends without reply until the position to be seized is actually reached. All three of these methods, I admit, are sufficiently difficult of execution; but the one by which we carried our point at Labadieville is certainly the least trying to human nature. The difficulty is that it can not be put in practice except on level ground, where the rear rank can keep well closed up; and even then the leading men are in some danger of having their heads blown off by the muskets of their supporting comrades. For instance, I had my neck scorched at Labadieville by the fire of one of my own soldiers.

And now let us ascend from tactics to strategy. The plan of the campaign was that Weitzel should drive the enemy down the Lafourche to Thibodeaux; that Colonel Thomas, with the Eighth Vermont and a colored regiment, should flank them there by way of the railroad from New Orleans; and that the Twenty-first Indiana with a force of gun-boats should seize Brashear City, and cut off their retreat across the Atchafalaya. To bring all this about, Mouton ought to have fought a second battle with us at Thibodeaux, or at least to have retired with a decent degree of deliberation. But he had been too neatly whipped and too thoroughly frightened to do either. He made a desperate rush for Brashear City, deserted at every step by his Lafourche militiamen, and succeeded in crossing the Atchafalaya almost in sight of the intercepting force, which had been detained two days off the bar by a furious norther. As for us, we followed him in a most leisurely manner, fearing that he would do just what he did. And now for nearly six months—that is, until General Banks arrived to open his Teche campaign—was Weitzel military master of the fertile Lafourche country, and commander of the United States forces in all Louisiana west of the Mississippi.

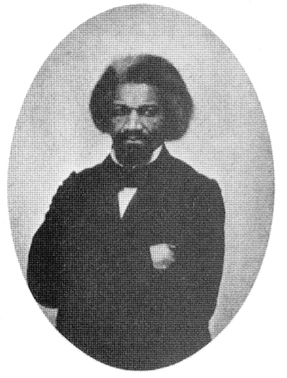

Frederick Douglass, 1856 (Courtesy of the University of New Mexico)