“The agitations and mental excitements of the war have, in the case of the writer, as in the case of many others, used up the time and strength which would have been devoted to authorship. Who could write on stories that had a son to send to battle, with Washington beleaguered and the whole country shaken as with an earthquake? Who could write fiction when fact was so imperious and terrible, in the days of Bull Run and Big Bethel?” With this explanation, Harriet Beecher Stowe, the best-selling author in America, ceased after two installments a story she was writing for the New York Independent. Six months later, when she resumed the tale, she informed her readers that “no great romance is coming,—only a story pale and colorless as real life, and sad as truth.”1

Stowe’s own “real life” was anything but “pale and colorless.” The daughter of Lyman Beecher, America’s fiery evangelical preacher, she lost her mother at age four and spent her childhood contemplating the most profound questions of religious faith. At age twenty-one, she moved with her family from Hartford to Cincinnati, where her father headed Lane Theological Seminary and where she met her husband, Calvin Ellis Stowe, a professor of Biblical literature. It was here that she became interested in the public questions of the day, especially abolition. And it was here that she began writing, publishing sketches in the Western Monthly Magazine.

In 1850 the Stowes returned to the East. Harriet was now physically closer to the brother with whom she had strong emotional links. Henry Ward Beecher had inherited his father’s pyrotechnics and applied them to the question of slavery. Harriet told her brother of her plans to write a book that would awaken the nation to the sin of slavery. Sometime that year, settled in Brunswick, Maine, she wrote about the death of a slave named Uncle Tom. From there, she derived the rest of the story and it appeared in installments between June 1851 and April 1852 in the National Era, an anti-slavery newspaper centered in Washington. Published in 1852, Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly became, next to the Bible, the best-selling book of the century.

A decade later, Abraham Lincoln met Mrs. Stowe at the White House. “So this is the little lady who made the big War,” he is reported to have said. Lincoln was simply being his droll self, but the comment is revealing. The Civil War was very much made by and of words, and every writer knew it. For Stowe, this knowledge carried a particular burden. Looked to for leadership, she had trouble deciding what to say. She could not write romance, but what could she write? The letters on behalf of her son Frederick came easily; afflicted by uncertain physical ailments, the withdrawal into family was comforting. But Stowe was a professional writer and a devoted opponent of slavery. She had to find a way during the Civil War to speak out. When she did, the result helped shape the outcome of the war as much as her work had initiated it.

In November 1862, over the course of two days, Stowe wrote a letter that was nearly ten years overdue. In 1853, she had received a document from the women of Great Britain and Ireland, some half-million of them, imploring their sisters in America to devote themselves to the destruction of slavery. The address remained unanswered until now, until the British themselves had disgusted Stowe and other Unionists with their tacit support of the Confederacy, until Lincoln had given assurances that the Emancipation Proclamation would indeed be issued on the first of January.

Stowe’s reply effectively rebuked the British for their inconsistencies and celebrated what she saw as the inexorable progress toward emancipation. It served as a vehicle for Stowe to re-emerge on the national scene as a spokesperson not only for the Union cause but for female moral authority. Published in January 1863, her reply also reinforced what was now widely known: Lincoln had indeed issued the Emancipation Proclamation. On the day of its signing, Stowe was present at the Boston Music Hall for the Emancipation Jubilee. When word finally arrived, her name was called out by the audience. She stood at the balcony and received cheers; it was the moment toward which she had been writing.

Stowe continued after that day. She knew all the abstractions of the war and she learned all the realities of it. Her son, wounded at Gettysburg, was never the same, living out his life in a confusion of pain and alcohol. Stowe herself suffered from headaches and facial paralysis. She increasingly invested her energies in the building of a new home and took to writing about home beautification for the Atlantic. Home was not merely a subject for essays, it was the emotional and symbolic fulcrum of her life. The war had balanced the “home nest.” It was time now to rebuild: “Home is the thing we must strike for now, for it is here that we must strengthen the things that remain.”2

Home would form a basis for the new Christian benevolence that must envelop the nation after the war. In the Chimney Sweep, published near the end of the war, Stowe fused her religious pieties with poetic visions of a regenerated landscape. As with many other writers and photographers at the time, Stowe imagined that nature would renew the lives wrenched and scarred by the sacrifices of war. She awaited the growth of “flowers of healing.” The lilac, in which she placed her hopes of rebirth, would within months be employed by Whitman as the flower of mourning.3

After the war, Stowe bought a home in Florida and spent many of her last years there. The ironies here run deep, for she partially abandoned her native state, Connecticut, for a Southern state where she even invested in schemes to raise cotton. In her writing, Stowe returned to the themes of her youth. The power behind her claim that Lord Byron had an incestuous relationship with his sister must have been connected at some level to her own complex family relations. Accusations put her at the center of a public controversy that damaged her reputation. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was still a presence in the country; its author less so. She spent her last years drifting, not so much in space as in mind: “now I rest me, like a moored boat, rising and falling on the water, with loosened cordage and flapping sail.”4 Before slipping out of view on the horizon, she had forever shifted the currents of history.

I am writing with a pencil in bed because I am too much worn out today to get up—Ever since war was declared which is now about two weeks—a little over—I have been like a person struggling in a night mare dream—Fred7 immediately wanted to go—& I was willing he should, if he could only get a situation where he could do any good—But as a mere soldier I felt he was not strong enough & might therefore only get sick & do no good—He applied to go as a surgeon’s aid—but as he was only in his first year of study & so many graduated medical men applied he could not get any situation of that kind. At last Mrs. Field’s8 brother Dr. Adams (a splendid fellow who is surgeon of the first regiment) said that if Fred would enlist with him as a private he would immediately choose him for Hospital Steward when the army got in action—

I can’t describe the confusion in the house when Fred came rushing up Saturday before last with the news that he was going. I was lying in bed quite worn out having done a great deal about the house that day—Immediately I got up late as it was & we hurried & threw his & my things together …. [B]y Friday all was ready & I took him to Boston…. He may start off any time or minute….

Fred & I had a long talk Saturday night & he said he was willing to lay down his life cause & that if he died he felt he should go to the pure & good he always longed for & he & I kneeled down hand in hand and prayed for each other…. This is no holiday frolic or child’s play but it is taking the plunge of life in real earnest…. This has come like a whirlwind this war so that really I have yet got things adjusted yet.

Yesterday noon Henry came in, saying that the Commonwealth, with the First Regiment on board, had just sailed by. Immediately I was of course eager to get to Jersey City to see Fred. Sister Eunice10 said she would go with me, and in a few minutes she and I were in a carriage, driving towards the Fulton Ferry. Upon reaching Jersey City we found that the boys were dining in the depot, an immense building with many tracks and platforms. It has a great cast-iron gallery just under the roof, apparently placed there with prophetic instinct of these times. There was a crowd of people pressing against the grated doors, which were locked, but through which we could see the soldiers. It was with great difficulty that we were at last permitted to go inside, and that object seemed to be greatly aided by a bit of printed satin that some man gave Mr. Scoville.11

When we were in, a vast area of gray caps and blue overcoats were presented. The boys were eating, drinking, smoking, talking, singing, and laughing. Company A was reported to be here, there, and everywhere. At last S. spied Fred in the distance, and went leaping across the tracks towards him. Immediately afterwards a blue-overcoated figure bristling with knapsack and haversack, and looking like an assortment of packages, came rushing towards us.

Fred was overjoyed, you may be sure, and my first impulse was to wipe his face with my handkerchief before I kissed him. He was in high spirits, in spite of the weight of the blue overcoat, knapsack, etc., etc., that he would formerly have declared intolerable for half an hour. I gave him my handkerchief and Eunice gave him hers, with a sheer motherly instinct that is so strong within her, and then we filled his haversack with oranges.

We stayed with Fred about two hours, during which time the gallery was filled with people, cheering and waving their handkerchiefs. Every now and then the band played inspiriting airs, in which the soldiers joined with hearty voices. While some of the companies sang, others were drilled, and all seemed to be having a general jollification. The meal that had been provided was plentiful, and consisted of coffee, lemonade, sandwiches, etc.

On our way out, we were introduced to the Rev. Mr. Cudworth, chaplain of the regiment. He is a fine-looking man, with black eyes and hair, set off by a white havelock. He wore a sword, and Fred, touching it, asked, “Is this for use or ornament, sir?”

“Let me see you in danger,” answered the chaplain, “and you’ll find out.”

I said to him I supposed he had had many a one confided to his kind offices, but I could not forbear adding one more to the number. He answered, “You may rest assured, Mrs. Stowe, I will do all in my power.”

We parted from Fred at the door. He said he felt lonesome enough Saturday evening on the Common in Boston, where everybody was taking leave of somebody, and he seemed to be the only one without a friend, but that this interview made up for it all.

I also saw young Henry. Like Fred he is mysteriously changed, and wears an expression of gravity and care. So our boys come to manhood in a day….

The time has come … when such an astonishing page has been turned in the anti-slavery history of America, that the women of our country, feeling that the great anti-slavery work to which their English sisters exhorted them is almost done, may properly and naturally feel moved to reply to their appeal, and lay before them the history of what has occurred since the receipt of their affectionate and Christian address.

Your address reached us just as a great moral conflict was coming to its intensest point.

The agitation kept up by the anti-slavery portion of America, by England, and by the general sentiment of humanity in Europe, had made the situation of the slaveholding aristocracy intolerable. As one of them at the time expressed it, they felt themselves under the ban of the civilized world. Two courses only were open to them: to abandon slave institutions, the sources of their wealth and political power, or to assert them with such an overwhelming national force as to compel the respect and assent of mankind. They chose the latter.

To this end they determined to seize on and control all the resources of the Federal Government, and to spread their institutions through new States and Territories until the balance of power should fall into their hands and they should be able to force slavery into all the Free States.

A leading Southern senator boasted that he would yet call the roll of his slaves on Bunker Hill; and, for a while, the political successes of the Slave Power were such as to suggest to New England that this was no impossible event.

They repealed the Missouri Compromise, which had hitherto stood, like the Chinese wall; between our Northwestern Territories and the irruptions of slaveholding barbarians.

Then came the struggle between Freedom and Slavery in the new Territory,—the battle for Kansas, and Nebraska, fought with fire and sword and blood, where a race of men, of whom John Brown was the immortal type, acted over again the courage, the perseverence, and the military religious ardor of the old Covenanters of Scotland, and, like them, redeemed the Ark of Liberty at the price of their own blood and blood dearer than their own.

The time of the Presidential canvass which elected Mr. Lincoln was the crisis of this great battle. The conflict had become narrowed down to the one point of the extension of slave-territory. If the slaveholders could get States enough, they could control and rule; if they were outnumbered by Free States, their institutions, by the very law of their nature, would die of suffocation. Therefore, Fugitive-Slave Law, District of Columbia, Inter-State Slave-Trade, and what not, were all thrown out of sight for a grand rally on this vital point. A President was elected pledged to opposition to this one thing alone,—a man known to be in favor of the Fugitive-Slave Law and other so-called compromises of the Constitution, but honest and faithful in his determination on this one subject. That this was indeed the vital point was shown by the result. The moment Lincoln’s election was ascertained, the slaveholders resolved to destroy the Union they could no longer control.

They met and organized a Confederacy which they openly declared to be the first republic founded on the right and determination of the white man to enslave the black man, and, spreading their banners, declared themselves to the Christian world of the nineteenth century as a nation organized with the full purpose and intent of perpetuating slavery.

But in the course of the struggle that followed, it became important for the new Confederation to secure the assistance of foreign powers, and infinite pains were then taken to blind and bewilder the mind of England as to the real issues of the conflict in America.

It has been often and earnestly asserted that slavery had nothing to do with this conflict; that it was a mere struggle for power; that the only object was to restore the Union as it was, with all its abuses. It is to be admitted that expressions have proceeded from the National Administration which naturally gave rise to misapprehension, and therefore we beg to speak to you on this subject more fully.

And, first, the declaration of the Confederate States themselves is proof enough, that, whatever may be declared on the other side, the maintenance of slavery is regarded by them as the vital object of their movement…. On the other hand, the declarations of the President and the Republican party, as to their intention to restore “the Union as it was,” require an explanation. It is the doctrine of the Republican party, that Freedom is national and Slavery sectional; that the Constitution of the United States was designed for the promotion of liberty, and not of slavery; that its framers contemplated the gradual abolition of slavery; and that in the hands of an anti-slavery majority it could be so wielded as peaceably to extinguish this great evil.

They reasoned thus. Slavery ruins land, and requires fresh territory for profitable working. Slavery increases a dangerous population, and requires an expansion of this population for safety. Slavery, then, being hemmed in by impassable limits, emancipation in each State becomes a necessity.

By restoring the Union as it was the Republican party meant the Union in the sense contemplated by the original framers of it, who, as has been admitted by [Alexander] Stephens, … were from principle opposed to slavery. It was, then, restoring a status in which, by the inevitable operation of natural laws, peaceful emancipation would become a certainty.

In the mean while, during the past year, the Republican Administration, with all the unwonted care of organizing an army and navy, and conducting military operations on an immense scale, have proceeded to demonstrate the feasability of overthrowing slavery by purely Constitutional measures. To this end they have instituted a series of movements which have made this year more fruitful in anti-slavery triumphs than any other since the emancipation of the British West Indies.

The District of Columbia, as belonging strictly to the National Government, and to no separate State, has furnished a fruitful subject of remonstrance from British Christians with America. We have abolished slavery there, and thus wiped out the only blot of territorial responsibility on our escutcheon.

By another act, equally grand in principle, and far more important in its results, slavery is forever excluded from the Territories of the United States.

By another act, America has consummated the long-delayed treaty with Great Britain for the suppression of the slave-trade. In ports where slave-vessels formerly sailed with the connivance of the port-officers the Administration has placed men who stand up to their duty, and for the first time in our history the slave-trader is convicted and hung as a pirate. This abominable secret traffic has been wholely demolished by the energy of the Federal Government.

Lastly, and more significant still, the United States Government has in its highest official capacity taken distinct anti-slavery ground, and presented to the country a plan of peaceable emancipation with suitable compensation. This noble-spirited and generous offer has been urged on the Slaveholding States by the Chief Executive with an earnestness and sincerity of which history in aftertimes will make honorable account in recording the events of Mr. Lincoln’s administration.

Now, when a President and Administration who have done all these things declare their intention of restoring “the Union as it was” ought not the world fairly to interpret their words by their actions and their avowed principles? Is it not necessary to infer that they mean by it the Union as it was in the intent of its anti-slavery framers, under which, by the exercise of normal Constitutional powers, slavery should be peaceably abolished?

We are aware that this theory of the Constitution has been disputed by certain Abolitionists; but it is conceded, as you have seen, by the Secessionists. Whether it be a just theory or not is, however, nothing to our purpose at present. We only assert that such is the professed belief of the present Administration of the United States, and such are the acts by which they have illustrated their belief.

But this is but half the story of the anti-slavery triumphs of this year. We have shown you what has been done for freedom by the simple use of the ordinary Constitutional forces of the Union. We are now to show you what has been done to the same end by the Constitutional war-power of the nation.

By this power it has been this year decreed that every slave of a Rebel who reaches the lines of our army becomes a free man; that all slaves found deserted by masters become free men; that every slave employed in any service for the United States thereby obtains his liberty; and that every slave employed against the United States in any capacity obtains his liberty; and lest the army should contain officers disposed to remand slaves to their masters, the power of judging and delivering up slaves is denied to army-officers, and all such acts are made penal.

By this act, the Fugitive-Slave Law is for all present purposes practically repealed. With this understanding and provision, wherever our armies march, they carry liberty with them. For be it remembered that our army is almost entirely a volunteer one, and that the most zealous and ardent volunteers are those who have been for years fighting with tongue and pen the Abolition battle. So marked is the character of our soldiers in this respect, that they are now familiarly designated in the official military dispatches of the Confederate States as “The Abolitionists.” Conceive the results, when an army, so empowered by national law, marches through a slave-territory. One regiment alone has to our certain knowledge liberated two thousand slaves during the past year, and this regiment is but one out of hundreds….

It is conceded on all sides, that, wherever our armies have had occupancy, there slavery has been practically abolished. The fact was recognized by President Lincoln in his last appeal to the loyal Slave States to consummate emancipation.

Another noticeable act of our Government in behalf of Liberty is the official provision it makes for the wants of the thousands of helpless human beings thus thrown upon our care. Taxed with the burden of an immense war, with the care of thousands of sick and wounded, the United States Government has cheerfully voted rations for helpless slaves, no less than wages to the helpful ones. The United States Government pays teachers to instruct them, and overseers to guide their industrial efforts. A free-labor experiment is already in successful operation among the beautiful sea-islands in the neighborhood of Beaufort, which, even under most disadvantageous circumstances, is fast demonstrating how much more efficiently men will work from hope and liberty than from fear and constraint. Thus, even amid the roar of cannon and the confusion of war, cotton-planting, as a free-labor institution, is beginning its instant life, to grow hereafter to a glorious manhood.

Lastly, the great, decisive measure of the war has approached,-The President’s Proclamation of Emancipation.

This also has been much misunderstood and misrepresented in England. It has been said to mean virtually this:—Be loyal, and you shall keep your slaves; rebel, and they shall be free.

But let us remember what we have just seen of the purpose and meaning of the Union to which the rebellious States are invited back. It is to a Union which has abolished slavery in the District of Columbia, and interdicted slavery in the Territories,—which vigorously represses the slave-trade, and hangs the convicted slaver as a pirate,—which necessitates emancipation by denying expansion to slavery, and facilitates it by the offer of compensation. Any Slaveholding States which should return to such a Union might fairly be supposed to return with the purpose of peaceable emancipation. The President’s Proclamation simply means this:—Come in, and emancipate peaceably with compensation; stay out, and I emancipate, nor will I protect you from the consequences….

And now, Sisters of England, in this solemn, expectant hour, let us speak to you of one thing which fills our hearts with pain and solicitude.

It is an unaccountable fact, and one which we entreat you seriously to ponder, that the party which has brought the cause of Freedom thus far on its way, during the past eventful year, has found little or no support in England. Sadder than this, the party which makes Slavery the chief corner-stone of its edifice finds in England its strongest defenders.

The voices that have spoken for us who contend for Liberty have been few and scattering. God forbid that we should forget those few noble voices, so sadly exceptional in the general outcry against us! They are, alas, too few to be easily forgotten. False statements have blinded the minds of your community, and turned the most generous sentiments of the British heart against us. The North are fighting for supremacy and the South for independence, has been the voice. Independence? for what? to do what? To prove the doctrine that all men are not equal. To establish the doctrine that the white may enslave the negro.

It is natural to sympathize with people who are fighting for their rights; but if these prove to be the right of selling children by the pound and trading in husbands and wives as merchantable articles, should not Englishmen think twice before giving their sympathy? A pirate-ship on the high seas is fighting for independence! Let us be consistent.

It has been said that we have been over-sensitive, thin-skinned. It is one inconvenient attendant of love and respect, that they do induce sensitiveness. A brother or father turning against one in the hour of trouble, a friend sleeping in the Gethsemane of our mortal anguish, does not always find us armed with divine patience.12 We loved England; we respected, revered her; we were bound to her by ties of blood and race. Alas! must all these declarations be written in the past tense? …

This very day the writer of this has been present at a solemn religious festival in the national capital, given at the home of a portion of those fugitive slaves who have fled to our lines for protection,—who, under the shadow of our flag, find sympathy and succor. The national day of thanksgiving was there kept by over a thousand redeemed slaves, and for whom Christian charity had spread an ample repast. Our Sisters, we wish you could have witnessed the scene. We wish you could have heard the prayer of a blind old negro, called among his fellows John the Baptist, when in touching broken English he poured forth his thanksgivings. We wish you could have heard the sound of that strange rhythmical chant which is now forbidden to be sung on Southern plantations,—the psalm of this modern exodus,—which combines the barbaric fire of the Marseillaise with the religious fervor of the old Hebrew prophet.

Oh, go down Moses,

’Way down into Egypt’s land

Tell King Pharoah

To let my people go!….

As we were leaving, an aged woman came and lifted up her hands in blessing. “Bressed be de Lord dat brought me to see dis first happy day of my life! Bressed be de Lord!” In all England is there no Amen?

We have been shocked and saddened by the question asked in an association of Congregational ministers in England, the very blood-relations of the liberty-loving Puritans,—“Why does not the North let the South go?”

What! give up the point of emancipation for these four million slaves? Turn our backs on them, and leave them to their fate? What! leave our white brothers to run a career of oppression and robbery, that, as sure as there is a God that ruleth in the armies of heaven, will bring down a day of wrath and doom?

Is it any advantage to people to be educated in man-stealing as a principle, to be taught systematically to rob the laborer of his wages, and to tread on the necks of weaker races? Who among you would wish your sons to become slave-planters, slave-merchants, slave-dealers? And shall we leave our brethren to this fate? Better a generation should die on the battle-field, that their children may grow up in liberty and justice. Yes, our sons must die, their sons must die. We give ours freely; they die to redeem the very brothers that slay them; they give their blood in expiation of this great sin, begun by you in England, perpetuated by us in America, and for which God in this great day of judgment is making inquisition in blood.

In a recent battle fell a Secession colonel, the last remaining son of his mother, and she a widow. That mother had sold eleven children of an old slave-mother, her servant. That servant went to her and said,—“Missis, we even now. You sold all my children. God took all yours. Not one to bury either of us. Now, I forgive you.”

In another battle fell the only son of another widow. Young, beautiful, heroic, brought up by his mother in the sacred doctrines of human liberty, he gave his life an offering as to a holy cause. He died. No slave-woman came to tell his mother of God’s justice, for many slaves have reason to call her blessed.

Now we ask you, Would you change places with that Southern mother? Would you not think it a great misfortune for a son or daughter to be brought into such a system?—a worse one to become so perverted as to defend it? Remember, then, that wishing success to this slavery-establishing effort is only wishing to the sons and daughters of the South all the curses that God has written against oppression. Mark our words! If we succeed, the children of these very men who are now fighting us will rise up to call us blessed. Just as surely as there is a God who governs in the world, so surely all the laws of national prosperity follow in the train of equity; and if we succeed, we shall have delivered the children’s children of our misguided brethren from the wages of sin, which is always and everywhere death….

You may imagine the anxiety with which we waited for news from you after the battle. The first we heard was on Monday morning from the paper, that you were wounded in the head. On hearing this your Father set off immeidately to go to you & took the twelve o’clock train to Boston & the five o’clock New York cars to go right on to Baltimore.

Before he left Andover we got a telegraph from Robert saying that you were wounded, but not dangerously and would be sent home in a few days.

At Springfield that night a gang of pick pockets hustled your father among them as he was getting out of the cars & took from him his pocket book containing 130 dollars & all the letters which your sisters & I wrote to you—He went on to Baltimore & when he arrived there was so sick as to have to send for a doctor who told him that he was going to be very sick & must go back immediately where he could be taken care of.

He however saw a Mr. Clark (uncle of our student Clark) who was going on to Gettysburg to attend to the wounded, & Gen. H. Wilson who both promised to look for you.

Several other friends also volunteered & Papa returned to Brooklyn where Jack Howard nursed him & this morning Saturday the 11th he is home & in bed—quite unwell but not so but what good news from you would revive him—Do get some one to write for you & tell us how to visit [?], & what we shall do for you.—Do let us know when we may expect you—We have been looking for you every night, all your sisters waiting at the cars—We must see you & return thanks [one illegible word] that your life is saved. God bless you. At last you have helped win a glorious victory. The cause is triumphant! God be thanked!—Your loving mother.

Here comes the First of January, Eighteen Hundred and Sixty-Five, and we are all settled comfortably into our winter places, with our winter surroundings and belongings; all cracks and openings are calked and listed, the double windows are in, the furnace dragon in the cellar is ruddy and in good liking, sending up his warming respirations through every pipe and register in the house; and yet, though an artificial summer reigns everywhere, like bees, we have our swarming-place,—in my library. There is my chimney-corner, and my table permanently established on one side of the hearth; and each of the female genus has, so to speak, pitched her own winter-tent within sight of the blaze of my camp-fire….

Peaceable, ah, how peaceable, home and quiet and warmth in winter! And how, when we hear the wind whistle, we think of you, O our brave brothers, our saviours and defenders, who for our sake have no home but the muddy camp, the hard pillow of the barrack, the weary march, the uncertain fare,—you, the rank and file, the thousand unnoticed ones, who have left warm fires, dear wives, loving little children, without even the hope of glory or fame,—without even the hope of doing anything remarkable or perceptible for the cause you love,—resigned only to fill the ditch or bridge the chasm over which your country shall walk to peace and joy! Good men and true, brave unknown hearts, we salute you, and feel that we, in our soft peace and security, are not worthy of you! When we think of you, our simple comforts seem luxuries all too good for us, who give so little when you give all!

But there are others to whom from our bright homes, our cheerful firesides, we would fain say a word, if we dared.

Think of a mother receiving a letter with such a passage as this in it! It is extracted from one we have just seen, written by a private in the army of Sheridan, describing the death of a private. “He fell instantly, gave a peculiar smile and look, and then closed his eyes. We laid him down gently at the foot of a large tree. I crossed his hands over his breast, closed his eyelids down, but the smile was still on his face. I wrapped him in his tent, spread my pocket-handkerchief over his face, wrote his name on a piece of paper, and pinned it on his breast, and there we left him: we could not find pick or shovel to dig a grave.” There it is!—a history that is multiplying itself by hundreds daily, the substance of what has come to so many homes, and must come to so many more before the great price of our ransom is paid!

What can we say to you, in those many, many homes where the light has gone out forever?—you, O fathers, mothers, wives, sisters, haunted by a name that has ceased to be spoken on earth,—you, for whom there is no more news from the camp, no more reading of lists, no more tracing of maps, no more letters, but only a blank, dead silence! The battle-cry goes on, but for you it is passed by! the victory comes, but, oh, never more to bring him back to you! your offering to this great cause has been made, and been taken; you have thrown into it all your living, even all that you had, and from henceforth your house is left unto you desolate! O ye watchers of the cross, ye waiters by the sepulchre, what can be said to you? We could almost extinguish our own home-fires, that seem too bright when we think of your darkness; the laugh dies on our lip, the lamp burns dim through our tears, and we seem scarcely worthy to speak words of comfort, lest we seem as those who mock a grief they cannot know.

But is there no consolation? Is it nothing to have had such a treasure to give, and to have given it freely for the noblest cause for which ever battle was set,—for the salvation of your country, for the freedom of all mankind? Had he died a fruitless death, in the track of common life, blasted by fever, smitten or rent by crushing accident, then might his most precious life seem to be as water spilled upon the ground; but now it has been given for a cause and a purpose worthy even the anguish of your loss and sacrifice. He has been counted worthy to be numbered with those who stood with precious incense between the living and the dead, that the plague which was consuming us might be stayed. The blood of these young martyrs shall be the seed of the future church of liberty, and from every drop shall spring up flowers of healing. O widow! O mother! blessed among bereaved women! there remains to you a treasure that belongs not to those who have lost in any other wise,—the power to say, “He dies for his country.” In all the good that comes of this anguish you shall have a right and share by virtue of this sacrifice. The joy of freedmen bursting from chains, the glory of a nation new-born, the assurances of a triumphant future for your country and the world,—all these become yours by the purchase-money of that precious blood.

Besides this, there are other treasures that come through sorrow, and sorrow alone. There are celestial plants of root so long and so deep that the land must be torn and furrowed, ploughed up from the very foundation, before they can strike and flourish; and when we see how God’s plough is driving backward and forward and across this nation, rending, tearing up tender shoots, and burying soft wild-flowers, we ask ourselves, What is He going to plant?

Not the first year, nor the second, after the ground has been broken up, does the purpose of the husbandman appear. At first we see only what is uprooted and ploughed in,—the daisy drabbled, and the violet crushed,—and the first trees planted amid the unsightly furrows stand dumb and disconsolate, irresolute in leaf, and without flower or fruit. Their work is under the ground. In darkness and silence they are putting forth long fibres, searching hither and thither under the black soil for the strength that years hence shall burst into bloom and bearing.

What is true of nations is true of individuals. It may seem now winter and desolation with you. Your hearts have been ploughed and harrowed and are now frozen up. There is not a flower left, nor a blade of grass, not a bird to sing,—and it is hard to believe that any brighter flowers, any greener herbage, shall spring up, than those which have been torn away: and yet there will. Nature herself teaches you to-day. Out-doors nothing but bare branches and shrouding snow; and yet you know that there is not a tree that is not patiently holding out at the end of its boughs next year’s buds, frozen indeed, but unkilled. The rhododendron and the lilac have their blossoms all ready, wrapped in cere-cloth, waiting in patient faith. Under the frozen ground the crocus and hyacinth and the tulip hide in their hearts the perfect forms of future flowers. And it is even so with you: your leaf-buds of the future are frozen, but not killed; the soil of your heart has many flowers under it cold and still now, but they will yet come up and bloom.

The dear old book of comfort tells of no present healing for sorrow. No chastening for the present seemeth joyous, but grievous, but afterwards it yieldeth peaceable fruits of righteousness. We, as individuals, as a nation, need to have faith in that AFTERWARDS. It is sure to come,—sure as spring and summer to follow winter.

There is a certain amount of suffering which must follow the rending of the great chords of life, suffering which is natural and inevitable; it cannot be argued down; it cannot be stilled; it can no more be soothed by any effort of faith and reason than the pain of a fractured limb, or the agony of fire on the living flesh. All that we can do is to brace ourselves to bear it, calling on God, as the martyrs did in the fire, and resigning ourselves to let it burn on. We must be willing to suffer, since God so wills. There are just so many waves to go over us, just so many arrows of stinging thought to be shot into our soul, just so many faintings and sinkings and revivings only to suffer again, belonging to and inherent in our portion of sorrow; and there is a work of healing that God has placed in the hands of Time alone.

Time heals all things at last; yet it depends much on us in our suffering, whether time shall send us forth healed, indeed, but maimed and crippled and callous, or whether, looking to the great Physician of sorrows, and coworking with him, we come forth stronger and fairer even for our wounds….

The report of every battle strikes into some home; and heads fall low, and hearts are shattered, and only God sees the joy that is set before them, and that shall come out of their sorrow. He sees our morning at the same moment that He sees our night,—sees us comforted, healed, risen to a higher life, at the same moment that He sees us crushed and broken in the dust; and so, though tenderer than we, He bears our great sorrows for the joy that is set before us….

The apathy of melancholy must be broken by an effort of religion and duty. The stagnant blood must be made to flow by active work, and the cold hand warmed by clasping the hands outstretched towards it in sympathy or supplication. One orphan child taken in, to be fed, clothed, and nurtured, may save a heart from freezing to death; and God knows this war is making but too many orphans.

It is easy to subscribe to an orphan asylum, and go on in one’s despair and loneliness. Such ministries may do good to the children who are thereby saved from the street, but they impart little warmth and comfort to the giver. One destitute child housed, taught, cared for, and tended personally, will bring more solace to a suffering heart than a dozen maintained in an asylum. Not that the child will probably prove an angel, or even an uncommonly interesting mortal. It is a prosaic work, this bringing up of children, and there can be little rosewater in it. The child may not appreciate what is done for him, may not be particularly grateful, may have disagreeable faults, and continue to have them after much pains on your part to eradicate them,—and yet it is a fact, that to redeem one human being from destitution and ruin, even in some homely every-day course of ministrations, is one of the best possible tonics and alternatives to a sick and wounded spirit.

But this is not the only avenue to beneficence which the war opens. We need but name the service of hospitals, the care and education of the freedmen,—for these are charities that have long been before the eyes of the community, and have employed thousands of busy hands: thousands of sick and dying beds to tend, a race to be educated, civilized, and Christianized, surely were work enough for one age; and yet this is not all. War shatters everything, and it is hard to say what in society will not need rebuilding and binding up and strengthening anew. Not the least of the evils of war are the vices which a great army engenders wherever it moves,—vices peculiar to military life, as others are peculiar to peace. The poor soldier perils for us not merely his body, but his soul. He leads a life of harassing and exhausting toil and privation, of violent strain on the nervous energies, alternating with sudden collapse, creating a craving for stimulants, and endangering the formation of fatal habits. What furies and harpies are those that follow the army, and that seek out the soldier in his tent, far from home, mother, wife, and sister, tired, disheartened, and tempt him to forget his troubles in a momentary exhilaration, that burns only to chill and to destroy! Evil angels are always active and indefatigable, and there must be good angels enlisted to face them; and here is employment for the slack hand of grief. Ah, we have known mothers bereft of sons in this war, who have seemed at once to open wide their hearts, and to become mothers to every brave soldier in the field. They have lived only to work,—and in place of one lost, their sons have been counted by thousands.

And not least of all the fields for exertion and Christian charity opened by this war is that presented by womanhood. The war is abstracting from the community its protecting and sheltering elements, and leaving the helpless and dependent in vast disproportion. For years to come, the average of lone women will be largely increased; and the demand, always great, for some means by which they may provide for themselves, in the rude jostle of the world, will become more urgent and imperative.

Will any one sit pining away in inert grief, when two streets off are the midnight dance-houses, where girls of twelve, thirteen, and fourteen are being lured into the way of swift destruction? How many of these are daughters of soldiers who have given their hearts’ blood for us and our liberties!

Two noble women of the Society of Friends have lately been taking the gauge of suffering and misery in our land, visiting the hospitals at every accessible point, pausing in our great cities, and going in their purity to those midnight orgies where mere children are being trained for a life of vice and infamy. They have talked with these poor bewildered souls, entangled in toils as terrible and inexorable as those of the slave-market, and many of whom are frightened and distressed at the life they are beginning to lead, and earnestly looking for the means of escape. In the judgment of these holy women, at least one third of those with whom they have talked are children so recently entrapped, and so capable of reformation, that there would be the greatest hope in efforts for their salvation. While such things are to be done in our land, is there any reason why any one should die of grief? One soul redeemed will do more to lift the burden of sorrow than all the blandishments and diversions of art, all the alleviations of luxury, all the sympathy of friends….

In such associations and others of kindred nature, how many of the stricken and bereaved women of our country might find at once a home and an object in life! Motherless hearts might be made glad in a better and higher motherhood; and the stock of earthly life that seemed cut off at the root, and dead past recovery, may be grafted upon with a shoot from the tree of life which is in the Paradise of God.

So the beginning of this eventful 1865, which finds us still treading the winepress of our great conflict, should bring with it a serene and solemn hope, a joy such as those had with whom in the midst of the fiery furnace there walked one like unto the Son of God.

The great affliction that has come upon our country is so evidently the purifying chastening of a Father, rather than the avenging anger of a Destroyer, that all hearts may submit themselves in a solemn and holy calm still to bear the burning that shall make us clean from dross and bring us forth to a higher national life. Never, in the whole course of our history, have such teachings of the pure abstract Right been so commended and forced upon us by Providence. Never have public men been so constrained to humble themselves before God, and to acknowledge that there is a Judge that ruleth in the earth. Verily His inquisition for blood has been strict and awful; and for every stricken household of the poor and lowly, hundreds of households of the oppressor have been scattered. The land where the family of the slave was first annihilated, and the negro, with all the loves and hopes of a man, was proclaimed to be a beast to be bred and sold in market with the horse and the swine,—that land, with its fair name, Virginia, has been made a desolation so signal, so wonderful, that the blindest passer-by cannot but ask for what sin so awful a doom has been meted out. The prophetic vision of Nat Turner, who saw the leaves drop blood and the land darkened, have been fulfilled. The work of justice which he predicted is being executed to the uttermost.

But when this strange work of judgment and justice is consummated, when our country, through a thousand battles and ten thousands of precious deaths, shall have come forth from this long agony, redeemed and regenerated, then God Himself shall return and dwell with us, and the Lord God shall wipe away all tears from all faces, and the rebuke of His people shall He utterly take away.

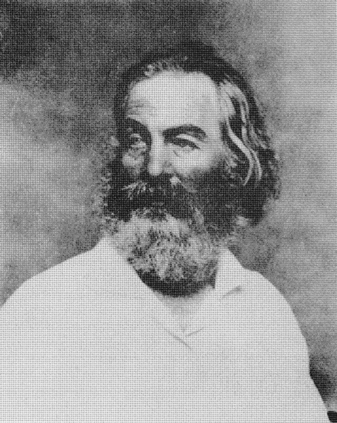

Walt Whitman, photographed by Mathew Brady, 1862 (Courtesy of the National Archives)