2

Pricing Americans Out of Health Care

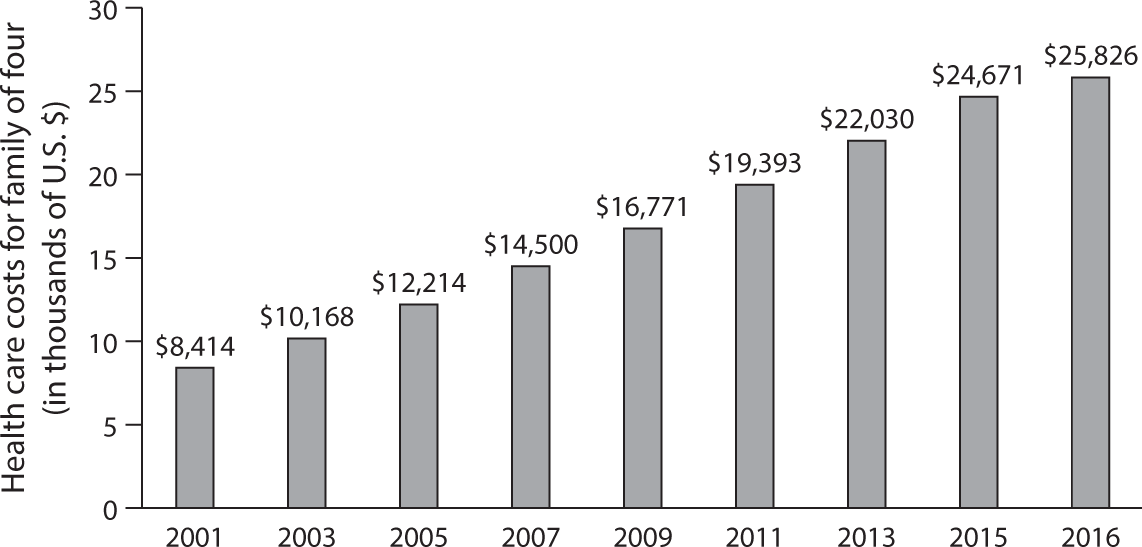

The Milliman Medical Index

How affordable is U.S. health care? The high cost of health care in the United States threatens inexorably to price kindness out of the souls of an otherwise kind people.

To see why millions of Americans are increasingly priced out of health care as we know it, we can confront the so-called Milliman Medical Index (see figure 2.1), which shows data on the distribution of income and wealth in the United States.

The Milliman Medical Index is tracked by the well-known actuarial firm Milliman, which draws on a database of several million insured American families. The index shows total spending for health care for a typical American family of four (with ages under sixty-five) covered by employment-based preferred provider organization (PPO) health insurance. “Total spending” in the index is defined as the sum of

- the employer’s contribution to the family’s insurance coverage, plus

- the employee’s contribution to the premium for that coverage, plus

- the family’s out-of-pocket spending.

Figure 2.1 Milliman Medical Index of Health Care Cost for Family of Four Covered by Employment-Based PPO, 2016.

Source: http://

PPO health insurance contracts sponsored by employers are widely regarded as the benchmark for good health insurance in the United States. They are thought to provide the kind of coverage that, ideally, every American should have. Most Americans debating health policy or designing health reform legislation have this form of coverage.

The virtue of the Milliman Index is that it includes out-of-pocket spending by families. The current debate on health reform typically focuses only on whether insurance premiums rise or fall, as if that were the proper metric for judging the affordability of health care. It is not. Total spending matters.

Figure 2.1 shows the time path of this index from 2001, when it stood at $8,414, to 2016, when it had reached $25,826. For 2017 the index rose again, to $26,944, an increase of $1,118. That number may seem extraordinary, but less so when one recalls that per capita health spending in the United States stood at $10,209 in 2017.

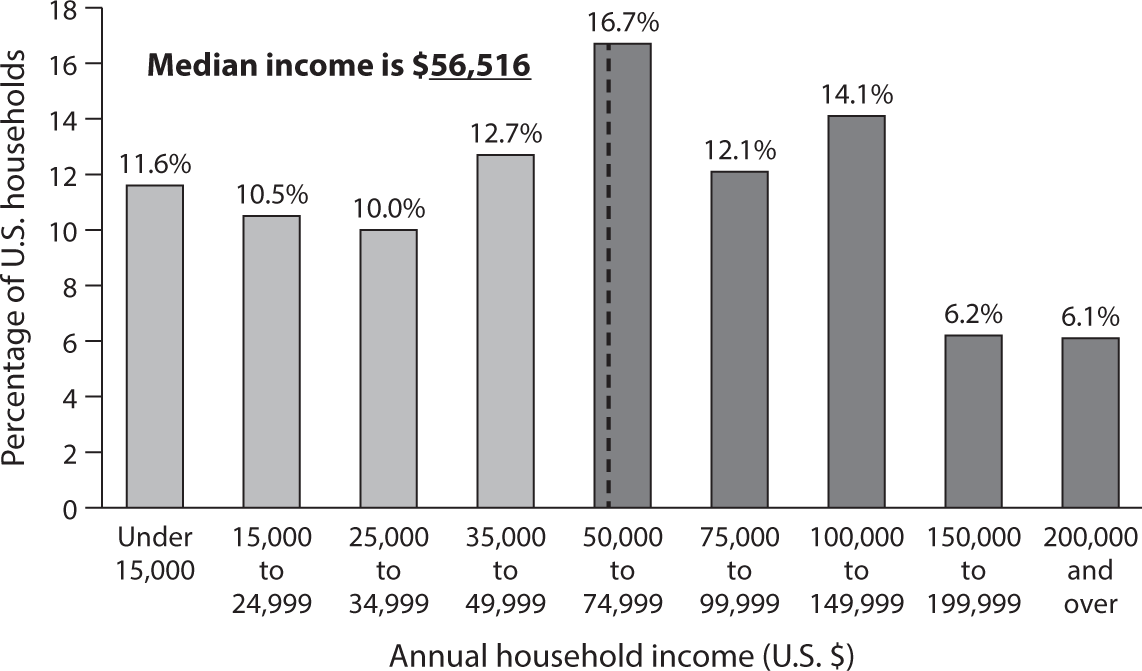

Figure 2.2 Percentage Distribution of Household Income in the United States in 2015.

Source: Data from Statista, 2015.

The level of these numbers and their growth over time are remarkable. They suggest that, so far, the private health insurance sector has not been able to control the growth of health spending any better than has the public sector. For both sectors, health care spending has risen apace, although a bit more slowly in the past decade than before.

The Distribution of Income and Wealth in the United States

Now contrast the Milliman Medical Index with the distribution of household income and wealth in the United States, shown in figures 2.2 and 2.3. As figure 2.2 shows, in 2015 the distribution of annual money income1 of U.S. households had a median of $56,516. Half of U.S. households had a lower income than that. Almost a third had an income of $35,000 or less.

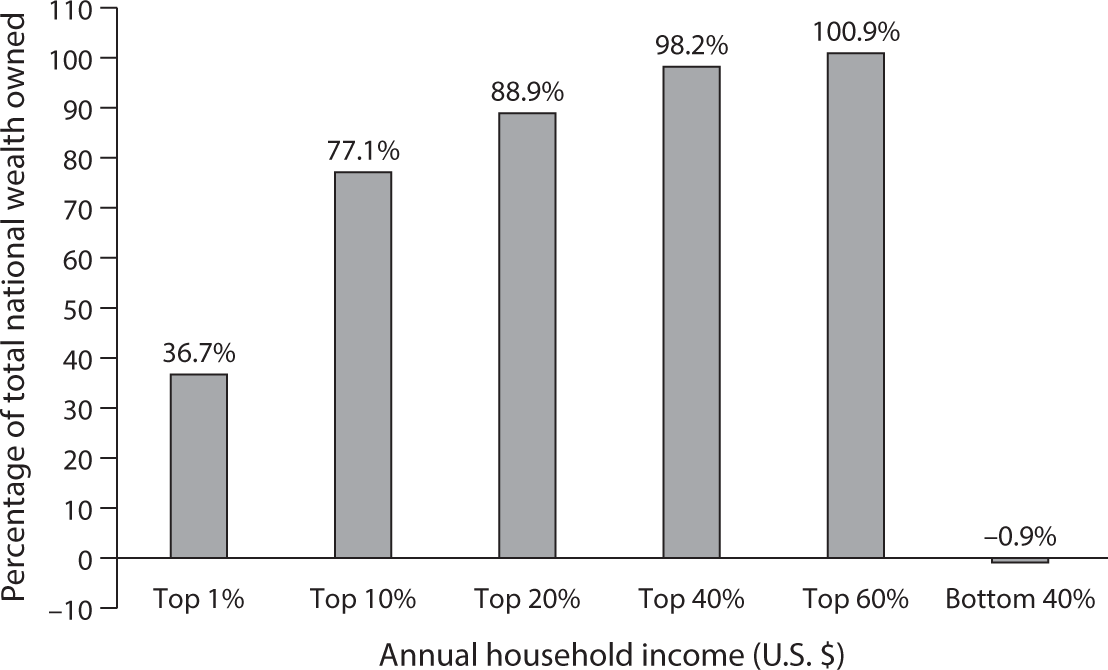

Figure 2.3 Distribution of Wealth in the United States, 2013.

Source: Edward N. Wolff, www

For a U.S. family of four covered by an employment-based PPO contract, about half of the median income of $56,000 would be claimed by health care alone if that family had to cover the annual health spending of $27,000 (2017) out of its own household budget. That median income would not even be enough to cover the annual cost of, say, a new cancer drug or other new biological drugs.

The Stark Choices Confronting U.S. Health Policy Makers

The high and growing cost of U.S. health care, combined with the inequality in the distribution of income and wealth among American families, confronts U.S. health policy makers with the following stark choices:

- If it is desired that all Americans have access to roughly the same kind of health care on terms they can afford with their own, often small household budgets, then purchasing power for health care must be transferred somehow from households in the upper strata of the income distribution to families in the lower strata. There are several mechanisms by which this transfer of money could be achieved.

- However, if those transfers are politically impossible, then access to health care and its quality must be rationed somehow by income class. This would result in a multitiered health system, with a medical Disneyland for the well-to-do (now called “boutique medicine”2) at the top, a bare-bones system for the poor at the bottom, and different tiers in between, depending on patients’ ability to pay. For the most part, lower-income American families would be priced out of health care as families in the upper half of the income distribution know it and prefer it.

- A third alternative would be to copy the approaches used in other countries to control the level and growth of the cost of health care, which would include more uniformity in fee schedules and outright price regulation.

If health policy makers opted for the first choice, they could use several vehicles for transferring money from high- to low-income households, to wit:

- Explicit taxes and transfers through public budgets.

- Community-rated health insurance premiums that are the same for healthy and sick individuals in large risk pools, thus forcing younger and healthier individuals to subsidize through their premiums the health care of older and sicker individuals.

- Price discrimination, whereby prices for some patients are set high to help finance deep price discounts extended to poor patients or outright charity care.

In the United States we have used all three transfer mechanisms in the past.

The first transfer mechanism—explicit taxes and transfers—is used for Medicare, Medicaid, Tricare for military families, Veterans Administration (VA) care for veterans, and so on. Economists favor it because these transfers are explicit rather than hidden, and politicians can be held accountable for them.

The second transfer mechanism—community-rated health insurance premiums (of which more further on)—has been a hallmark of Obamacare. As is well known, it has created huge actuarial problems3 in that context. It also has burdened healthier members of the middle class who are asked to subsidize sicker individuals. More will be said about these problems further on as well.

Apparently unbeknownst to many Americans covered by employment-based insurance, community rating also is baked into that system. Two employees performing the same work for a given company, one healthy and the other one chronically ill, usually make the same contribution out of their paychecks toward their insurance coverage. In other words, healthy employees indirectly subsidize chronically ill employees.

Can we imagine the outcry among employees—especially unionized employees—if a company tried to extract a larger contribution toward health insurance from chronically ill employees than from chronically healthy employees? Or can we imagine how elderly and most likely sicker members of Congress and their staffs would react if their contribution to their health insurance coverage were not community rated but instead based on actuarially fair pricing, taking each member’s health status into account?

The third transfer mechanism—price discrimination—also is an integral feature of the U.S. health care delivery system. Doctors, hospitals, and other providers of health care routinely engage in it. Clever public relations people can pitch it as an angelic Robin Hood–like mechanism that robs the rich to help the poor. However, that system also can serve as a perfect platform for outright financial rapaciousness, visiting great financial distress on members of the middle class.4