7

The Mechanics of Commercial Health Insurance from an Ethical Perspective

As noted earlier, private health insurance in the United States, as the final payer that pays doctors, hospitals, and other providers of health care, is responsible for about one-third of the total health spending in the United States. Insurers collect premiums from their policy holders to write checks to doctors, hospitals, and other providers of health care.

The pricing of health insurance through premiums can take two quite distinct forms:

- medically underwritten (actuarially fair) health insurance premiums based on the individual applicant’s health status, and

- community-rated premiums that are the same for all individuals in large risk pools composed of chronically healthy and chronically sick members.

This chapter explains the differences among these pricing approaches with a simple, stylized numerical example, emphasizing the problems that can arise when community-rated premiums are not supported by a strictly enforced mandate on everyone—young and old—to be insured. That problem has bedeviled the Affordable Care Act of 2010 (Obamacare).

The High Concentration of U.S. Health Spending

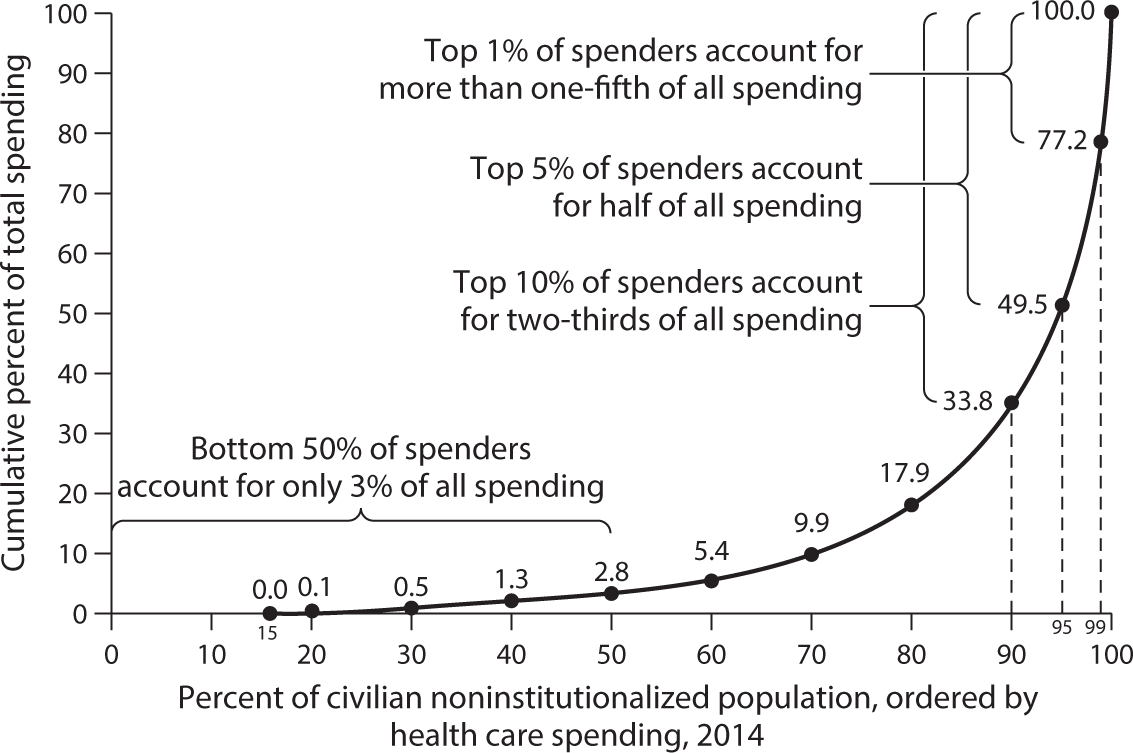

Well known to any health policy expert, but perhaps not to the laity, is that in any given year health care spending is concentrated among a few very sick individuals. Figure 7.1 illustrates this phenomenon for the year 2014.

Half the U.S. population did not use much health care at all in 2014. About 90 percent of the population accounted for only 35 percent of all health spending. The most expensive 10 percent of the population accounted for about two-thirds of all health spending, and the most expensive 1 percent for almost 22 percent of all health spending.

This high concentration of health spending among a few individuals is observed for any large group of healthy and sick individuals—for example, employees of large business firms, or large groups of people with mixed health status in any country. Actuaries refer to this as the “80-20” Rule, because typically for any large group of healthy and less healthy people, 20 percent of that group account for roughly 80 percent of that group’s health spending.

This concentration curve is roughly the same every year, although U.S. health spending has become slightly more concentrated over the past four decades or so.

Individuals in the upper, most expensive segment of this concentration curve fall into several distinct groups:

- At one extreme are healthy individuals who met with bad luck during the year because of unforeseen trauma or severe illness.

- At the other extreme are chronically ill individuals, usually with multiple chronic conditions, who require sustained, expensive medical treatment, typically involving ever more expensive drug therapy.

- In between are individuals not in perfect health, with various degrees of chronic illness.

Figure 7.1 Health Care Spending Is Highly Concentrated Among a Small Portion of the U.S. Non-Institutionalized Population.

Source: National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation (NIHCM) analysis of data from the 2013 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, reprinted with permission.

Pricing Health Insurance in Unregulated Commercial Markets

Based on the medical histories submitted to them, insurance actuaries usually can accurately classify individuals into distinct risk groups.

A distinct risk group is defined as one all of whose members have, ex ante, the same probability distribution of likely future medical expenditures. Another way of saying this is that each member has the same probability of incurring a particular medical expense.

For a large enough membership in the group—more than 20,000 or so—actuaries can then calculate the probability-weighted average (also called the actuarial average or the mathematical expectation) of the risk group’s expected per capita medical expenses in the next period (year). Once again, ex post, within such a risk pool, most members will be lucky and have no or only very low actual medical expenses. Only a few unlucky ones will have high expenses. Ex post, the lucky members of the pool will help finance the health care used by the unlucky ones through the premium they had paid at the beginning of the insurance period. Most economists do not view this as income redistribution, but as the central idea of all forms of insurance.

If an insurer collects from every member of a distinct risk class a premium equal to the probability-weighted expected average medical expense—the actuarial average cost for that risk pool—then the total sum collected should be precisely enough to cover all medical expenses of all members of the pool. The technical jargon for such a premium is actuarially fair.

To that actuarially fair premium the insurer will then add a load factor (think of it as a percentage markup) to cover the cost of marketing and administration and to yield a profit margin. The actuarially fair premium plus the load factor then constitute the premium charged the insured.

|

Table 7.1 A Simple Stylized Numerical Illustration of the Pricing Strategy of Commercial Health Insurance |

||||||

|

Size of medical bill |

Fraction of Risk Pool A expected to incur such a medical bill |

Fraction of Risk Pool B expected to incur such a medical bill |

Fraction of Merged Risk Pools A and B expected to incur such a medical bill |

|||

|

$0 |

0.85 |

0.55 |

0.700 |

|||

|

$5,000 |

0.11 |

0.36 |

0.235 |

|||

|

$30,000 |

0.03 |

0.06 |

0.045 |

|||

|

$100,000 |

0.01 |

0.03 |

0.020 |

|||

|

Probability-weighted Average |

$2,450 |

$6,600 |

$4,525 |

|||

The natural instinct of commercial insurers is to price health insurance this way. Because the probability-weighted expected average medical expenses for risk pools with sicker people are higher than those for pools of healthy people, the premiums charged chronically sicker people naturally will be higher than those charged healthier people. A simple, highly stylized numerical example can illustrate this pricing strategy.

“Actuarially Fair” vs. “Community-Rated” Premiums

Imagine, then, that future health spending could take on only four levels: $0, $5,000, $30,000, and $100,000, as shown in table 7.1.

Assume that in any coming year, people will experience only one of the four medical expenditure levels in the table. The probability of falling into a particular expenditure level, however, varies by risk pool. Table 7.1 shows only two distinct pure risk pools, A and B. Individuals in Pool A are relatively healthy and have a high probability of falling into low expenditure levels. Individuals in Pool B are less healthy. They have a high probability of falling into higher expenditure levels.

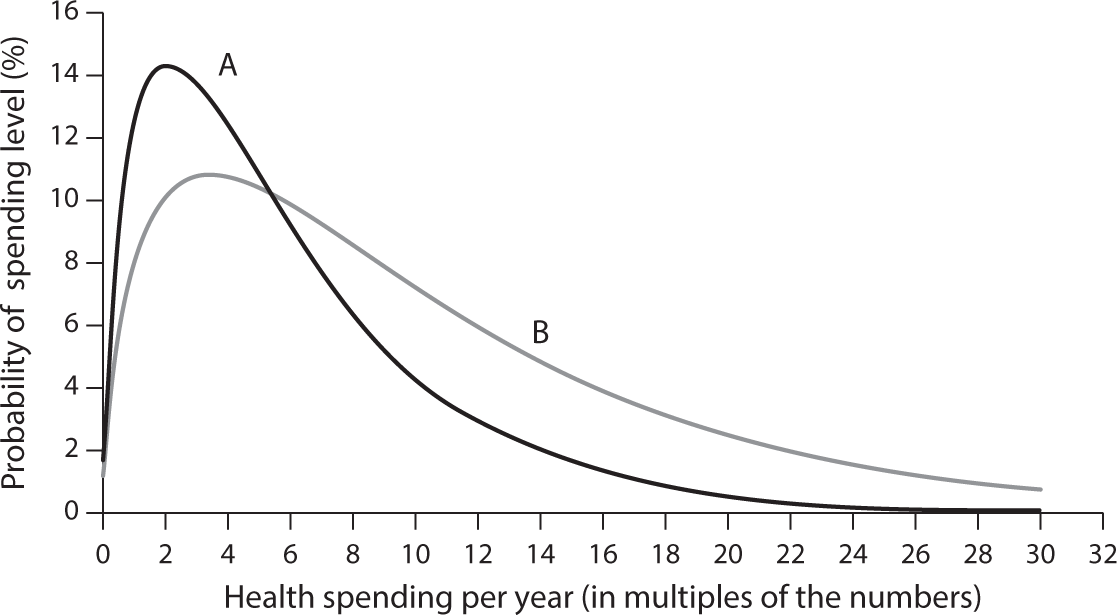

Figure 7.2 Probability Levels of Health Spending Per Capita at Different Levels of Chronic Illness.

In real life, there would of course be myriad different expenditure levels, and each risk group would be characterized by a probability curve, such as those shown in figure 7.2.

As already noted, actuaries can accurately predict the probability-weighted average level of spending of particular risk groups exceeding 20,000 members. The relevant actuarial averages for each risk group shown are seen in the bottom row of table 7.1.

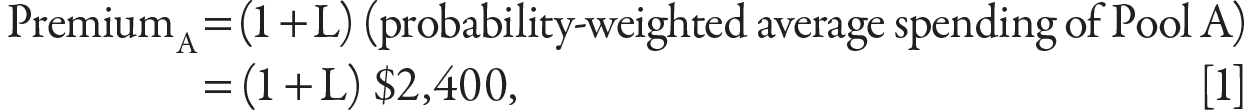

In a competitive but otherwise unregulated health insurance market, an insurer would assess from the medical histories submitted by applicants for insurance into which risk pool, A or B, individual applicants fall. Applicants falling into Pool A would then be charged a premium equal to

where L is a loading factor to cover marketing, administration, and profits.1

Similarly, the insurer would charge each member of Pool B a premium equal to

That premium is much higher than the premium for Pool A because, on average, members of Pool B are sicker and more expensive to the insurer than those in Pool A.

Premiums that are based on the health status of the individual applicant are also called medically underwritten premiums. The term means that these premiums are based on detailed medical histories that applicants for health insurance must submit to the insurer to allow the latter to price health insurance actuarially fairly.

This approach to pricing health insurance obviously represents a deep intrusion by perfect strangers in a distant insurance company into very private, personal matters. With data files of even large companies so vulnerable to hacking, it is a daunting prospect.

Medical underwriting also raises the administrative cost of such a system. In fact, prior to passage of the Affordable Care Act of 2010, health insurance policies sold in the nongroup market were medically underwritten. Not surprisingly, because actuaries had to pore over each applicant’s medical history, up to 45 percent or so2 of the premiums charged individuals were devoted by insurers to marketing, administration, and profits, leaving only slightly more than half of the premium to purchase actual health care for the insured. It is amazing that anyone thought this a good bargain.

Although medically underwritten insurance premiums make sense to actuaries, economists, and commercial insurance executives, they typically are decried by members of the general public who consider it unfair to charge sicker people higher health insurance premiums. Within the present stylized example, there would be populist political pressure to merge members of Groups A and B into one joint risk pool (the “community”) and to price health insurance for each member of that joint group as

Such a premium is defined as community rated over the wider risk pool of chronically healthy and chronically sick individuals (the “community”). The Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandated such an approach to insurance pricing for all insurers selling policies in the small-group and nongroup insurance markets. (“Non-group” here means the market in which Americans as individuals purchase health insurance coverage.)

With community-rated premiums, members of the healthy Group A would pay a much higher premium than they would under actuarially fair pricing. On the other hand, members of the sicker Group B would pay a lower premium than under actuarially fair pricing.

In other words, community-rated premiums force ex ante a redistribution of income from relatively healthier to relatively sicker individuals in the risk pool. As we have learned with Obamacare, that redistribution can rankle the healthier people.

Are Community-Rated Premiums Fair?

A policy question now being hotly debated is whether the income redistribution from healthy to sick Americans that is forced by community-rated health insurance premiums is fair. Should community rating be abandoned in favor of medically underwritten (actuarially fair) premiums, which are higher for sick individuals than for healthier individuals?

Before examining this question in the American context, we should note that most of the world regards community-rated health insurance premiums as ethically defensible, that is, as “fair.”

- It is so, for example, in the first national health insurance model, Germany’s Bismarckian model, introduced by German chancellor Otto von Bismarck in 1883 as a preemptive strike against the socialist stirrings of the day.

- It is so in all of the national health systems that have adopted slightly modified versions of the Bismarckian model—for example, the Swiss, French, Belgian, and Dutch systems, the Japanese system, and most of the Latin American systems.

- The Medicare Advantage program, under which Medicare beneficiaries may choose to obtain insurance coverage from private insurers, also uses community-rated premiums.

- Finally, as noted earlier, the U.S. employment-based health insurance system uses community-rated premiums, so far without much opposition from younger and healthier employees. It has prompted one commentator to ask wryly in her column, “Where is the outrage over employment-based coverage in the ‘rate shock’ debate [triggered by Obamacare]?”:

When it comes to complaints about redistribution and overly-generous benefits in health insurance, why is the echo chamber limited to the individual market? Where is the outrage over employer-sponsored insurance?3

- In fact, actuarially fair (medically underwritten) premiums in the United States were typical only in the small sliver of the health insurance market for individually purchased health insurance (about seven million insured), until Obamacare imposed community-rated premiums on that small market segment as well, to give people in the non-group market the same community rating Americans have under employment-based coverage.

Some Americans, however, including some legislators, do consider community-rated premiums unfair, even though most of them, if older, actually benefit from them. In an interview on MSNBC, for example, Congressman Mo Brooks (R-AL) argued that people who stay healthy deserve to pay lower premiums for their health insurance. In his words:

My understanding is that it [the Republican health-reform plan] will allow insurance companies to require people who have higher health care costs to contribute more to the insurance pool that helps offset all these costs, thereby reducing the costs to those people who lead good lives, they’re healthy, they’ve done the things to keep their bodies healthy.

Similarly, when asked whether he agreed with late-night talk show host Jimmy Kimmel that every family, rich or poor, should have access to the kind of excellent care Mr. Kimmel’s child received after being born with a congenital heart defect, Mick Mulvaney, President Trump’s director of the Office of Management and Budget, responded:

I do think it [the Republican health reform bill] should meet that test. We have plenty of money to deal with that. We have plenty of money to provide that safety net so that if you get cancer you don’t end up broke … that is not the question.… That doesn’t mean we should take care of the person who sits at home, eats poorly and gets diabetes. Is that the same thing as Jimmy Kimmel’s kid? I don’t think that it is.4

This ethical perspective is based on the theory that lifestyle is a major determinant of health status, although clinical scientists constantly remind us that genetic factors, environmental factors, and in utero experiences as fetuses also play important roles in driving the health status of adults.

Part of the debate on social policy in this country has long been the issue of personal responsibility versus social responsibility for the plight of the nation’s vulnerable populations. Conservatives hold that much of that plight can be traced to personal irresponsibility. Progressives on the left argue that vulnerable people are the victims of their socioeconomic and cultural circumstances. The proper perspective undoubtedly lies somewhere in between. Behavior surely matters, but so does the socioeconomic and physical environment.

As of this writing, the third version of the 2017 health reform bill that actually was passed by the House of Representatives (H.R. 1628) would leave it up to the states to decide whether they wish to impose community rating on insurance companies or allow them to set actuarially fair premiums. That provision was not included in the Senate draft bill H.R. 1628 Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017.5

High-Risk Pools

When reminded that going back to pre-Obamacare, actuarially fair pricing might throw millions of relatively sick people off the insurance rolls, the defenders of actuarially fair premiums invariably mention that sicker Americans would be taken care of through so-called high-risk pools.

The problem with that riposte is twofold.

First, the history of high-risk pools in this country during the past several decades is strewn with pools that failed. The pools charged individuals premiums from 125 percent to 200 percent of the average premiums charged in the individual market and had very high deductibles and tight upper annual and lifetime limits. Furthermore, many of them were underfunded and limited enrollment to fit their underfunded budgets.

Second, politicians who allude to high-risk pools as a solution to the problems of chronically ill people (the jargon now is “people with pre-existing conditions”) owe it to voters to spell out precisely the parameters they have in mind for their high-risk pool, to wit:

- Precisely what will be the eligibility criteria to get into a high-risk pool?

- What will be the premiums charged individuals accepted into the high-risk pool relative to the average premium charged in the individual market?

- What are the specifics of the benefit package covered, which includes:

- Deductibles, coinsurance, and maximum annual risk exposure for enrollees

- Upper annual and lifetime limits on coverage

- Exclusions from coverage (e.g., maternity and newborn care, mental health care, and services for addicted people)

- Coverage of prescription drugs

Unless politicians proposing high-risk pools as a solution for people with serious pre-existing conditions are willing to provide voters with theses crucial details, they are effectively selling the voting public the proverbial pig in a poke. It should not be acceptable in a democracy.

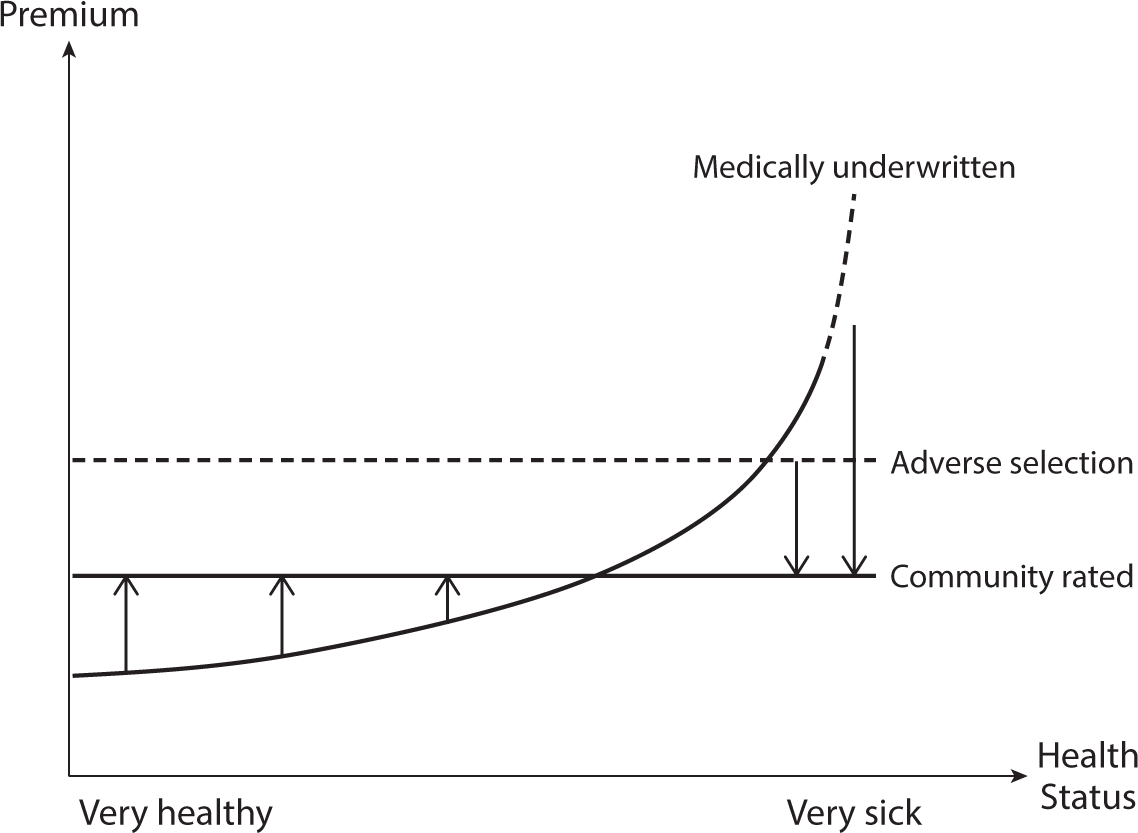

Figure 7.3 Medically Underwritten versus Community-Rated Premiums.

Community-Rated Premiums and the Death Spiral of Health Insurance

Figure 7.3 presents a hypothetical picture of actuarially fair and community rated premiums. It is only a rough sketch to make a point and is not based on real data. The curved line in the graph (designated “medically underwritten”) depicts actuarially fair premiums, and the solid horizontal line (designated “community related”) a community-rated premium, both lines for the same risk pool.

Because community rating clearly raises premiums of younger and healthier individuals above their true actuarial costs, these individuals have a strong incentive not to buy insurance, knowing that if they should fall seriously ill, they can then throw themselves upon the mercy of the community-rated premium. It is an open invitation to gaming the system, a maneuver actuaries call “adverse risk selection.”

In the graph, the upward-shifted dashed line (designated “adverse selection”) shows this effect. This higher community-rated premium will drive yet another cohort away from insurance coverage, which will further drive up the community-rated premium of the remaining, now much more expensive risk pool. Actuaries call this dynamic the “death spiral” of health insurance.

This death spiral is not just theory. It has been observed in real life in the states of New Jersey6 and New York, both of which imposed community rating on insurers without also mandating that all individuals must acquire health insurance. Because this dire outcome was perfectly predictable, one must wonder what the legislators in these two states were thinking when they passed the relevant bills into law.7

If insurers must sell coverage to anyone willing to pay a community-rated premium, individuals must be strictly mandated to purchase such coverage. Such a mandate, in turn, requires that public subsidies be paid to or on behalf of those low-income individuals unable to afford the mandated coverage with their own financial resources.

This mandate will anger voters all along the ideological spectrum. Critics on the right see it as trampling on the freedom of Americans. Critics on the left sometimes interpret it as just a means to drive new customers into the arms of greedy insurance companies. In fact, the mandate is an actuarial necessity.