CHAPTER 3

“LAW ENFORCEMENT IN HIGH GEAR”

For a year or more, two state police investigators, Ray Polett and Charlie Donoghue, spent their shifts, sometimes together and sometimes in rotation, sitting in a cellar, eavesdropping in hopes of hearing incriminating comments by suspects in the Egan murders.

“I hated that detail,” eighty-two-year-old Polett said in a March 2014 interview in his Punta Gorda, Florida home. “I suffered through that, sitting in a cold damp basement, being cold, hungry and thirsty, with cold feet, usually working it noon to eight at night. I met Donoghue working that case. I didn’t like him at first, but we became close. We were a lot like the odd couple, but we worked well together.”

An informant, not identified but old enough to have a seven-year-old grandson, allowed use of his home, about two blocks away from the targeted 315 High Street, Watertown home of Willard and Bertha Belcher, to listen to phone conversations. State police had burglarized the Belcher home to plant a bug. Polett said a trooper who was a locksmith got him and Donoghue into the house:

We were like the Keystone Cops. We overturned a sofa, pulled away the bottom fiber, then planted the bug in the sofa frame. Charlie had brought his staple gun from home, and I started using it to staple the fiber back into place. But the gun was empty. Charlie said it was loaded yesterday!

Now the clock was ticking. We had to get this done before Belcher got home, but we had to go across the city to Charlie’s house, get staples and come back. Luckily we got it done [about 10:00 p.m.], before they returned .

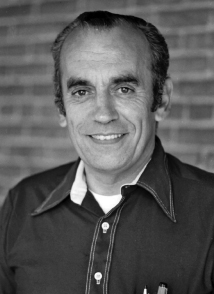

Raymond Polett.

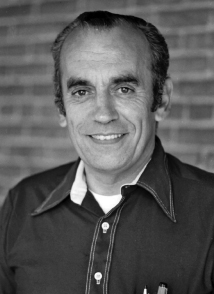

Charles Donoghue. Courtesy Mary Donoghue Fraser .

While enduring the discomforts of the cellar, the investigators had moments that occasionally broke the boredom in their assignment, Polett said. There was the day that the stakeout was nearly exposed, not by the suspects, but by the hosts’ grandson.

The boy came down the cellar stairs and saw Charlie and me. He ran back upstairs, put on a cowboy hat and toy gun, then came back down, pointed the gun at me, cocked it and pulled the trigger. I acted like I got hit and fell back. He ran back upstairs, and we never saw him again .

A favorite Willard Belcher term was “rat bastard,” Polett said, “and we heard him say, ‘I’d like to put a bullet in that rat bastard’s head’ a number of times. I heard him say that about me.”

But what the investigators needed to hear, they did not. “There was an exaggeration made that Willard was heard laughing and joking on the tapped line about how the Egans died. He never said anything to link anybody to the murders.”

Willard Belcher loved loud noises and was often heard in his phone chats making comments about big booms or bangs, Polett said. But there were no specific references to gunshots.

Most entertaining were calls taken by Bertha from her lovers, all close to her in age, Polett said. One old guy told her repeatedly how he really loved her, while another, bemoaning his impotence, was assured by Bertha, “Don’t worry, honey, I’ll take care of that,” Polett recalled with a chuckle.

Police had the goods on a prostitution case, but that wasn’t what they were looking for. “We were focused on getting murder charges,” he said.

THE BELCHERS AND JOSEPH LEONE were suspects “within days” of the triple homicide of December 31, 1964, according to Polett. “They had quite a few friends” who gave information during interviews, he said. “I’d say Leone’s name came up first. Many people were dropping his name.”

Joseph Richard Leone gave a statement to police on January 3, 1965, during which he made claims about his whereabouts at the time of the murders, according to a New York State Court of Appeals document.

Within the first month of the investigation, police said at least five hundred people were questioned, and to rule out a possible link to drug trafficking, the Buffalo branch of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics joined the probe. Also checked were known gamblers, but that proved to be a dead end in the search for a motive.

Investigator Donoghue told reporters that the quest for a motive was confounded by Peter Egan’s habit of bragging about his activities. “He had a vivid imagination in some of the stories he told,” Donoghue said, referring to several people he interviewed.

Donoghue offered his theory of what happened on New Year’s Eve: the killer “blew his top,” shot one Egan on the “spur of the moment” and then had to finish off the others.

Several people who were questioned agreed to take lie detector tests. Leone was among them, consenting on May 8, 1965, after state police informed him “they did not believe his account of his activities,” based on information they had developed, according to the court of appeals document. He was not administered the polygraph until July 1966, the court document indicates.

Everybody “passed,” police told reporters.

Leone was a guy who had been a standout football player when he attended Watertown’s Immaculate Heart Academy high school. He was the nice driver-salesman for Wonder Bread who gave treats to kids along the truck route that had been his for up to eighteen months. His niece called him her “favorite uncle—he was a good man and a great uncle.”

His friends saw him as mild-mannered, congenial, not a drinker and never in fights.

“Joe was very popular,” said James Pickett, who would be charged and then quickly uncharged in the investigation. “Everybody wanted to be Joe’s friend because his father was Kid Sullivan. Joe knew everybody everywhere he went.”

Kid Sullivan was actually Anthony G. Leone, who, born in Sicily, came to the United States in 1913, when he was thirteen, with his parents, Guiseppe and Francesca Ditta Leone. One of eight children in Guiseppe’s family, Anthony was in his mid- to late twenties when he entered the ring as a prizefighter to supplement his income as a construction worker and laborer.

“Boxing was big in the flats [a reference to an area of Watertown settled heavily by Italian immigrants], a good way to make money in the ’30s,” said Larry Corbett. “Get beat up.”

Relying on a rugged style of combat, Leone slugged his way in welterweight and middleweight divisions at Syracuse, Utica, Ogdensburg and Watertown in the 1930s. “Kid Sullivan,” whom the Watertown Times dubbed the “local caveman,” became a fan favorite at matches at the Knights of Columbus and Odd Fellows neighboring buildings on Stone Street and at the Starbuck Arena, across from New York Air Brake Company. His won-lost record was nothing to boast about, however.

There are stories to this day that Kid Sullivan even wrestled a bear, although there are no press reports to confirm this.

Murder suspect Joe Leone was at the time separated from his second wife, Anita, and was living with another woman, Beth Johnson. His first marriage, on February 18, 1950, to Norine, a fellow student at Immaculate Heart Academy, ended in divorce after five years. Before securing his job delivering bread, he had skipped around from one employer to another in Watertown, including the California Fruit Company store, Crescent Beverage Company and Arsenal Beverage Company. He also filled in as a gas station attendant.

Leone and Peter Egan were longtime friends and for many of their formative years had been neighbors.

Unsuspecting landlords of Joe Leone and Beth Johnson may not have been aware when an apparent piece of stolen property changed hands. The couple rented an apartment in the house at 114 Central Street owned and occupied by Cosmo and Rose Marie Amedeo. Leone knew that Cosmo was looking for a television set, and he told Peter Egan, who stopped in and said he had a TV to sell.

“Pete Egan was in my house once,” said Joseph Amedeo. “He sold my dad a TV. I’m positive it was hot. But my dad would not have knowingly bought stolen property.”

Mrs. Amedeo was a first cousin of popular singer Tony Bennett, who had visited their home.

Amedeo said he heard a few arguments between Joe and Beth, “and they sounded pretty bad, but not often, perhaps a couple times.”

Leone lived in the Amedeo duplex for about ten years, Amedeo said. “There was not a lot of coming and going” at the Leone apartment, he said.

Bertha Belcher was second oldest of four girls, born in 1897 to Frank and Mary Jane Smith Cushing. After Bertha’s father died while she was still a child, Mary Cushing moved the family to Gouverneur, New York, and remarried. That relationship had ended by 1920.

Bertha, in the meantime, experienced a failed marriage. She was about eighteen when, in 1915, she became Mrs. Lawrence Montondo, but the marriage was dissolved in 1919.

Little more than a decade later, Bertha Montondo’s name was beginning to appear on the Watertown police blotter. She first made headlines in May 1932, thanks to a Watertown police raid at her 457 Newell Street home. City police came searching for a man believed to be transporting alcoholic beverages. Although fourteen bottles of home brew were found in the house, and the runner was discovered in the attic of Bertha’s house, no arrests were reported.

She had moved to 238 Coffeen Street by April 1936, when Watertown police again visited her. Although Prohibition had been repealed by then, police conducted an investigation at Bertha’s house after a soldier assigned to Madison Barracks, Sackets Harbor, revealed that he had purchased liquor there. She was cited with keeping a disorderly house.

Eyes turned to her again in July 1938, when Bertha came under suspicion of running a house of prostitution at her newest address, 936 Arsenal Street. She, along with three other women and a man, was arrested in an investigation prompted by a man’s complaint that $300 in veterans’ bonus money had been stolen from him at her house. Prosecution fell through after the complainant was exposed as having served time in federal prison for attempted extortion.

But police were watching Bertha’s house, and before the year was over, on December 11, her home was raided. She and two women were arrested, and five men were charged with violating the public morality clause of a city ordinance. Bertha subsequently pleaded guilty to operating a disorderly house.

Ten years later, on October 3, 1948, she married Willard, the owner of a small trucking business. She was considerably older than him.

Bertha had a daughter, Sharon, who died at age five.

She “was a mean lady and ran a lot of houses of ill-repute,” one of her nieces said in an interview. “She was no mother figure to anyone but her working girls.”

The niece, wishing to not be identified, added, “She was a mean witch to all kids. When we visited our uncle and aunt, she was always mean, unfriendly and rotten to us.”

Bertha was also an abortionist, the niece and another source disclosed.

Willard was “a kind, outgoing, fun person to be around,” the niece said. This was her opinion, not Ray Polett’s.

“Willard really hated Donoghue and I,” Polett said in an interview, “telling me that ‘I could kill you, Polett.’ I responded that he probably could, but ‘you are too nice a guy to do that.’”

Willard, who was forty-nine when the Egans were gunned down, had apparently had only one encounter with the law, according to Watertown Times archives. That was in November 1962, when he was accused of assaulting his boss, Mitchell Roberts, at Deluxe Lines, a trucking business at 424 Newell Street in Watertown. Roberts had fired him for continually being late for work. Belcher pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct and returned to being a self-employed trucker.

A Valentine’s Day baby in 1915, Willard was one of four children whose alcoholic father, James, was known for beating his twenty-one-year-old wife of six years, Beatrice. The man of the house—a filthy apartment—was forcing his wife to have relations with immigrant highway workers to bring in money, alleged Watertown police, who in November 1915 charged James Belcher with living off the proceeds of prostitution. He escaped from the Jefferson County Jail and crossed the border to Canada, where he joined the army to serve in Cyprus in World War I, according to his descendants.

Family sources also say that Beatrice served prison time for harboring draft dodgers while James was serving in the Canadian army.

On September 22, 1919, the Belcher siblings, with a father living somewhere in Canada, became orphans. Their mother was lost when a freighter, the TJ Waffle , on which she was the only woman aboard, sank in a storm on Lake Ontario near Oswego, New York. The recovery of splintered debris led to speculation of a boiler explosion. Mrs. Belcher was the cook aboard the craft, which was bound for Kingston, Ontario, Canada, with a load of coal. She and all seven crewmen drowned. The body of a woman, headless and without hands or feet, was found the following year at “Toads Hole,” Dexter, and was presumed to be the remains of Beatrice Belcher. The remains were not positively identified and were buried in the Dexter cemetery.

When Willard was about eight years old, his father is said to have died in Canada from a lingering disease linked to his war service.

Willard’s remaining formative years were split between the western New York cities of Rochester and Buffalo, and by the time he returned to Watertown as a young man late in the 1930s, he had taken up boxing, entering the ring under the name “Kid Kelly” or “Kelly Belcher.”

IN THE SECOND FULL day of the investigation, state police were saying they believed there were at least two gunmen, but they had not yet arrived at a motive. Police were not about to say anything yet, but a turn of events three days later made it quite clear to the Watertown Daily Times that police were on to something. The paper observed in a January 5, 1965 editorial:

Coincidental or otherwise, the wheels of law enforcement, set into high gear following the investigation of the triple murders…have resulted in a series of arrests and the solution of crimes .

Since Sunday night seven persons have been taken into custody by the sheriff’s office for burglaries and criminally receiving stolen property…These minute investigations (by troopers, the sheriff and Watertown police) quickly led down other paths, apparently, and the series of arrests for burglaries followed .

It is interesting to note that an accused burglar had a business relationship with Peter W. Egan Jr .

The reference to an accused burglar involved a man identified as Earl William Bennett.

A part of the New Year’s Day investigation had troopers and deputies checking property on Military Road, Sackets Harbor, where Peter and Barbara Egan had been spending the last three weeks of their lives. Police found a .38-caliber Colt revolver hidden in a garage and a .32-caliber semiautomatic rifle tucked away in a chicken coop. The handgun, they determined, was not used in the murders, but what was interesting about the rifle was that it had been stolen from Seaway Sport Shop, at 521 West Main Street in Watertown.

Jefferson County sheriff Robert B. Chaufty revealed on January 6 that Bennett had sold the rifle to Peter Egan for fifteen dollars just ten days before the murders. Bennett, twenty-eight, was among three people arrested on Sunday, January 3, for burglary. Bennett admitted to obtaining the gun in a trade with a man living in the nearby village of Black River, the sheriff said.

Egan, according to Chaufty, had told Bennett, “I don’t know what the hell I’ll do with it.”

Bennett would later be convicted of second-degree grand larceny and was sentenced to probation. An accomplice, Gay O. Cooley Jr., twenty, pleaded guilty to attempted third-degree burglary.

The homicide investigation now had taken on a focus, and on the fourteenth day after the murders came the big break that police needed. Two more burglary arrests were made, and one of the suspects, who only recently had turned sixteen, had a story to tell. Investigators were all ears as Dale Glenn (an alias assigned by the authors) gave up the story of the Egan crime circle. The names he dropped would eventually send Polett and Donoghue into their eavesdropping hideaway.

Glenn, living in Canastota but formerly of Watertown, told police he was involved in at least forty burglaries in association with the Egans. He could not recall all the crimes, but he was able to list about half of them. One incident to which he admitted was at the home of Roy E. Dumas, on Black River Road near Watertown, which occurred thirteen days before the murders. The Egan brothers and Barbara were all involved, he said. Some coins were stolen, including a rare 1794 half dollar. Only about 5,300 such coins were believed to be in circulation. Today, five decades later, one in good condition might sell for more than $72,000.

Glenn told police he had accompanied the Egans to the home of Willard and Bertha Belcher on the night of the Dumas burglary, and he saw the half dollar being sold to Willard. The sale price was not disclosed, but Glenn revealed that his share for helping out in the theft was five dollars.

There was also a Christmas card from Gerald Egan that gave Glenn a bonus of $25. That brought to $100 his total take for participating in a spree of burglaries over the last seven months of the Egan trio’s lives.

State police alerted coin dealers and pawn shops about the hot half dollar and then waited until May before they were notified that it had changed hands. Investigators were informed that Willard Belcher had arranged a transaction through Carl E. Hofmann, a coin dealer in Syracuse, to sell the half dollar to Dr. Bennett Rosner of Fayetteville, New York.

No immediate action was taken to press charges. Instead, the bug was planted for the Polett-Donoghue effort. The public, meanwhile, could know only that a bunch of burglaries were being investigated.

Glenn, according to Inside Detective magazine, told police that the Egans sometimes sent out two different teams on a night to steal and loot. The Egans would make a big list on paper of the several places they intended to hit on a given day or night, police were told. Jim Brett, former Watertown Times reporter, suggested in an interview that Bertha did housecleaning at some of the burglary sites and told the Egans where her customers placed money and valuables.

With the information provided by Glenn, police put together the following list of solved cases in those final seven months:

June 6: Seaway Vending, 1543 State Street, ten cartons of cigarettes

June 22: Jeff Bottling Company, 449 Martin Street, associated with Pepsi-Cola Bottling Co., $1,000 cash

July 3: Mildred DeJourdan apartment, 203 Arsenal Street, $15,000 cash belonging to Ruth Sutton; DeJourdan and Sutton are sisters of Bertha Belcher

July 4: Seaway Vending again, $10

July 21: K.O. Charlebois Tire store, 465 Court Street, cash

August 26: Theodore Forepaugh residence, 1142 Arsenal Street, $1,600 in loot

August 26: Clobridge Plumbing and Heating, 454 Court Street, small change

August 26: Great Northern Salvage, 430 Court Street, attempt only

September 7: Robert Gow residence, 165 High Street, old coins, watches, rings

September 15: Francis Lyng residence, 810 Arsenal Street, $9.30 and $2.50 gold coin

September 15: Vacant house, 816 Arsenal Street, nothing missing

September 26: Martha Casler residence, 261 Paddock Street, nothing missing

September 27: Watertown Agway Co-op, 921 West Main Street, keys and $11

October 12: William Kumrow’s North Side Barber Shop, 508 LeRay Street, safe containing $1,530 coin collection

October 12: Emerson Laughland residence, 531 Hycliff Drive, watches and cigarette lighters

October 18: Forepaugh residence again, TV, mandolin and rifle

December 6: Gerald Smith residence, 228 Colorado Avenue, rare coins

December 18: Dumas residence, Black River Road, coins

December 21: Anthony Leone residence, 130 Duffy Street, $760 and ring

No date: Cody’s Grill, Brownville

No date: Trailer court office, outer Washington Street, no entry

No date: House on Route 180 near Limerick

The Watertown Times again took notice in its editorial column:

It is regrettable that it took a triple slaying to bring a solution to the numerous burglaries that had puzzled the authorities for months. The victims in the murder mystery had long been under surveillance by the police and county authorities but they worked cleverly and shrewdly in carrying out their criminal activities…One beneficial result of the Egan murders is the abrupt end to the numerous burglaries which have been a thorn in the side of the authorities for months. The Egans were the mainspring of the burglary wave and they had become expert in carrying out their program successfully until they came up against the wrong person or persons, suspected by the authorities of being identified with smalltime rackets .

The flurry of activity in January 1965 was followed by calm. For the next eighteen months, by all appearances, the investigation had fallen into dormancy. A Watertown Times reporter noticed in August that the Egan death car, held in storage at the Watertown state police headquarters since the murders, was no longer there. Investigators did not reveal where it had been taken, but the likely answer might have been to a laboratory for closer examination.

The Watertown Times and Syracuse newspapers asked on occasion if there were any new developments and were assured by state police that progress was being made.

“We definitely have some ideas” about the identity of the killers, senior investigator Jerome J. McNulty was quoted as saying on September 4, 1965. “The possibility of solution of the crime is brighter…we are making definite progress.”

Nearly four months later, on the first anniversary of the slayings, Captain Harold T. Muller added, “There are a few people who keep our interest.” The killings were “a local problem” linked to the rash of burglaries, he confirmed. Narcotics trafficking, gambling and a gangland hit had been ruled out, he said.

The person in the Chevy, the last person believed to have seen the Egans alive on Bradley Street, had been “tentatively” identified, he said. There would be no further revelation about that person’s identity, however.

“STOLEN COIN MAY BE CLUE IN EGAN CASE ”

The July 26, 1966 headline in the Watertown Daily Times announced new life in the homicide probe. All the talk about arrests in burglaries being a link to the triple murder probe, and all the certainty that the gunmen were local people, seemed to have subsided. Behind this curtain of silence, however, were Polett and Donoghue doing their listening and recording as Willard and Bertha had their telephone chats. Suddenly, that ended when the couple’s son, Gary, discovered the bug and pulled it.

“An alert neighbor tipped us off that a telephone truck was parked in our driveway while we weren’t home,” Gary Belcher said in an interview. “The neighbors watched our house with cat eyes.”

The time had come for state police to spring into action with the one solid lead they had. Willard Belcher, fifty-one, was arrested on a charge of receiving stolen property. The investigation about the half-dollar coin that was stolen from the Roy Dumas house thirteen days before the Egan murders was made public. Willard denied, of course, that the coin in question belonged to Dumas. He had purchased it from a coin dealer in Toronto, he claimed. He wasn’t sure of the dealer’s name—Hunt or Hunter, he suggested. Police checked it out. No coin dealer having any such name was found in Toronto.

On the day of Willard’s arrest, police alleged that Bertha gave permission for a search of their home. The search by Polett, Donoghue and state trooper Warren E. Creamer yielded an army .45-caliber pistol on the floor beneath a chest of drawers in a second-floor bedroom. Bullets were found in a drawer. The gun, however, was determined not to have been one of the murder weapons in the Egan deaths.

Willard and Bertha were charged with illegal possession of a firearm, but the count was eventually dropped for both on grounds of improper search and seizure methods. Willard was going to prison, however. Convicted of attempting to receive stolen property, he was sentenced to a term of two and a half to three and a half years.

Authorities had one of their suspects right where they wanted him, but not for murder. That was OK because now police could plant the seed for a war of nerves. When newspapers came out with second-anniversary stories about the unsolved murders, state police confirmed that an offer of immunity from prosecution was being considered for the murder accomplice who turned on the others. Such a move might have each of the killers fearing that the other might turn state’s evidence, police suggested.

Perhaps the strategy was striking a nerve. Was it only coincidental that Joe Leone, a known friend of the Belchers, a man already questioned in the murder investigation, was selling a piece of property within two months of the Willard Belcher arrest? A routine announcement on September 28, 1966, in the Watertown Daily Times disclosed that Leone had sold to his mother, Fern, a lot in the town of Watertown.

The investigation turned toward Carthage, about eighteen miles east of Watertown, following a shooting in that village on October 7, 1966. Three boys had been throwing vegetables at the home of Julius Ferry, at 547 Adelaide Street, and they took off running when the eighty-three-year-old property owner emerged with gun in hand. Mr. Ferry fired, wounding one of the kids, thirteen, in the thigh.

When police confiscated the weapon, they determined that it had been stolen. Mr. Ferry disclosed that he had obtained the gun a few years earlier from Peter Egan. A link to Egan was established, but as far as being connected to the homicide investigation, the gun proved to be a dead end for police. Charges were filed against Mr. Ferry, but five years later, a jury gave him an acquittal.

As state police continued their focus on the Belchers, they reviewed the recordings made during the eavesdropping. The bug did not pay off, Polett acknowledged. State police used what they could from tape recordings of phone conversations to obtain arrest warrants in the high-profile investigation.

“The basis for an arrest warrant was shaky,” Polett said. “We had nothing that strong to go with.”

Hence, evidence was subsequently obtained on the strength of a warrant that was partially based on the bug. “That would be an accurate thing to say,” Polett said.

Meanwhile, a Watertown police detective assisted state police by visiting a psychic. John C. Dawley brought his son Tom along. The psychic, according to Thomas Dawley, an eventual Watertown cop, said one killer spoke in broken English, had been a fighter and “had pictures all over him.” It was no secret that Belcher was a fighter, and he had tattoos, but his English was fine, Ray Polett said.

Police still had that kid burglar, Dale Glenn, who was being convicted for his admitted roles in burglaries and was being granted youthful offender status. As such, his records were being sealed by the court. Investigators talked to him again in early March 1968. The chat paid off. Glenn told police they needed to interview a man who had information about who killed the Egans. And Glenn told them who that man was: James H. Pickett.

The name had surfaced previously, although not disclosed by police, and certainly he had been questioned because Pickett was known to be a friend of the Egans. But hardly could this guy be seen as being knowledgeable about the murders. Just a couple months shy of his thirty-seventh birthday, he had no criminal record, and he was a family man, the father of two boys (one outside his marriage) and two girls ranging in age from two to about eighteen or nineteen.

A high school dropout, he had entered the army in 1949, and while stationed at Fort Meade, Maryland, he met a Baltimore girl about his age, Dolores. Upon discharge in 1952, he brought Dolores home to Watertown as his wife and settled into a civilian career of being a truck driver and heavy equipment operator.

Pickett was brought in for questioning, but investigators found him none too cooperative. They alleged that in two days of questioning, he “used deception in preventing state police from apprehending a person who has committed murder.”

According to Pickett, he was shown a death photo of Barbara Egan and was asked if he could identify her. After he could not, he said an investigator showed him a photo of a nude female corpse and asked, “Does this refresh your memory?”

Early in the afternoon of Saturday, March 23, 1968, troopers found Pickett at the Red Moon Diner, at 418 Court Street, and arrested him on a warrant charging first-degree hindering prosecution. The arrest, said District Attorney William J. McClusky in his fifteenth month as county prosecutor, marked a “major break” in the Egan murder probe. The arrest resulted from “new information,” something that left “nothing to change” the belief that the murders were tied to burglaries, he said. He added that more arrests could be expected in the “near future.” Polett, on the same day, added, “It really looks like things are going to develop.” Other arrests, he said, “are very imminent.”

Joe Leone enjoyed going to the movies. Apparently, that’s what he did on Sunday, March 24, either at the Town Theatre on Public Square, where West Side Story was showing, or at the Olympic Theatre on State Street, with America America as the featured film. As was his habit when a show let out, he stopped in at the State Restaurant, at 302 State Street, to hang out with some friends and play cards. A member of the group that evening—there were six to eight guys there—found nothing wrong with his demeanor. He was the same old Joe. At least one member of the group (his name is withheld by request) said he was totally unaware of Joe’s involvement in criminal activity.

Murder suspect Joseph R. Leone in custody at the Jefferson County Jail, guarded by Deputies Raymond Pacific (left) and Gordon Barker.

Likewise for Joe Amedeo. “I would never have thought that he could do anything like that. I always felt that Joe was a very nice guy,” said Amedeo, who was about nineteen when his in-house neighbor was arrested.

The next day, Leone was back at work. For a while.

“His truck was running late,” said Ray Polett. “When we finally arrested Leone, he was in his truck delivering bread and other baked goods for his employer. Donoghue and I staked out his route and finally saw Leone pull up to a stop” at the Genter and Brenon Grocery in Brownville.

Leone was actually a passenger in the truck, learning a new route, he said. “As he got out of his truck, we jumped out and collared him and took him into custody without incident.” Described by Polett as “in pretty good shape, athletic,” and by the Watertown Times as a “slim, quiet, dark-complexioned brown-eyed man with thinning brown hair,” Leone was brought to the state police station outside Watertown, where he was subjected to “an intense interview.”

“He was not impressed, to put it mildly,” Polett said. “Leone was one of the coolest people I ever met. While I was giving it my best shot, he took a nickel out of his pocket and coolly balanced it on edge, looked at me and grinned, to show me he wasn’t shook up.”

This Watertown Daily Times news clipping shows Bertha Belcher in custody on the night she was charged with being an accessory in the Egan murders. She was under the guard of Jefferson County sheriff Robert B. Chaufty and Mrs. Chaufty, who served as jail matron.

On the same afternoon, Bertha Belcher, seventy-one, was arrested at her home and was charged with being an accessory to murder.

Curiously, just four days earlier, Bertha had posted a $500 property bond for the release of the Egan brothers’ mother, Leona M. Egan, forty-nine, from the county jail. She had been charged by Watertown police with public intoxication in an early morning arrest in the parking lot at Phelps Apartments, at 232 West Main Street. Her live-in boyfriend, Delbert E. Leween, forty-three—a roofer remembered by Larry Corbett as “a quiet guy” who was a Canawaga Mohawk from Deseronto, Ontario, Canada—was arrested in the same incident on charges of disorderly conduct and resisting arrest.

Bertha was known for posting bail for her acquaintances, according to her son, Gary Belcher.

James Pickett alleged in an interview shortly before his death that Bertha was arrested because the murders were “all her idea; Bertha ran the show.” He characterized Bertha as a “mean, ruthless person” and claimed, “Everybody did what Bertha said.” He alleged that she disposed of the bloody clothes and weapons on the night of the murder.

Leone had known her for years, and “they were real tight,” Pickett said.

Leone and Bertha Belcher were taken on the evening of their arrests to the home of Pamelia town justice Allen S. Gardner for arraignment. “Both she [Bertha] and Leone appeared visibly shaken as they were led by troopers from the arraignment,” the Watertown Daily Times reported.

Reality had set in.Joe Leone appeared that night to no longer be the Mr. Cool whom Polett had confronted during questioning.

Joe Rich, a Channel 7 newsman at the time, remembers that night outside the Gardner home and the concerns it left for him and his wife:

I wanted to get film of Ma Belcher coming out of the justice’s home, but would I be able to flood the front of the home with enough light to get some good shots? A cameraman put out as many lights as he could find at the station on Champion Hill, and as soon as they exited the judge’s home, on went the lights, so bright that Ma Belcher had to cover her eyes. It was then that she yelled out, “Who did this?”

Someone yelled, “It was Joe Rich from Channel 7.” Everyone could hear her reply, “I’m going to get him for this.”

My wife, Carol, said after that she had observed a car that parked in front of our home on Gotham Street for several days .

Investigator Donoghue cautioned newsmen against making attempts to interview Leone or Mrs. Belcher, saying that any information should come from the district attorney.

On the same day Leone and Bertha Belcher were arrested, McClusky obtained a warrant charging a second person with murder. He delayed until Tuesday, March 27, to disclose the identification of the other accused killer: Willard Belcher. A warrant was filed at the Clinton Prison in Dannemora for the arrest of Belcher, who was serving his sentence in the Dumas stolen coin case. Within the next three days, the district attorney was informed that Belcher would likely never be eligible for prosecution. Several months earlier, he had been committed to a state hospital for the criminally insane at Dannemora.

“Willard Belcher was an odd man,” Pickett said. “He always walked the streets of Watertown carrying a loaded .45. Everybody was afraid of Willard because they knew he was certified crazy.”

The charge against Pickett was dropped after Leone and Bertha were arrested. When District Attorney McClusky was asked if the dismissal indicated that Pickett had suddenly decided to cooperate, he told a reporter, “Draw your own conclusion.”

Bertha Belcher was released on bond to await her day in court. Leone’s home for the next 667 days would be the county jail.

His jailers told the Watertown Times that Leone was a model prisoner and occupied his time by reading, playing cards and doing crossword puzzles. He also “had fun” peering out his barred window of the three-story jail located at the corner of Coffeen and North Massey Streets, watching state police divers search the Black River for the Egan murder weapons, Deputy Sheriff Thomas P. Belden told Joe Amedeo.

Watertown’s old Court Street Bridge, within view of the Jefferson County Jail, spanned the Black River where police were told the Egan murder weapons were tossed.

State trooper James L. Lafferty on a boat assists diver Matt Holmes in a search in the Black River for murder weapons. The guns were never found.

Diving efforts were conducted in April 1968 and again in August in the vicinity of the Court Street Bridge, within view of the jail. The August effort coincided with a lowering of the water depth from about twenty feet to six feet for the demolition of a nearby dam. But the guns were never found “because they didn’t look in the right God damn place,” Pickett told one of the authors.

Meanwhile, as McClusky prepared to convene a grand jury to hear the murder case, he was irked by a Watertown Times decision to list the names of ten potential witnesses. He was concerned that name disclosure could place witnesses in fear of reprisal. Attorney Paul R. Shanahan, of Syracuse, representing Leone, and Donald M. Palmer, of Watertown, Mrs. Belcher’s lawyer, were not concerned. A guilty defendant “knows who the witnesses are,” said Palmer. Besides, the disclosure helps an attorney to prepare his defense for an innocent client, he said.

Those named by the paper were four state police members, Donoghue, McNulty, Robert VanBenschoten and William Anderson; Dr. Lee; Pickett; Beth Johnson; Richard Wood; and Leona Egan and her live-in boyfriend, Delbert Leween.