Over twenty years ago the British clinical psychologist Richard Bentall (1992) offered “a proposal to classify happiness as a psychiatric disorder.” Noting that happiness is “statistically abnormal, consists of a discrete cluster of symptoms” and, further, that “there is at least some evidence that it reflects the abnormal functioning of the central nervous system” (p. 97), Bentall argued that it meets the most fundamental criteria used to justify many psychiatric diagnoses.

Those readers familiar with debates in the field of mental health would immediately have recognised that Bentall’s tongue was firmly in his cheek. Rather than making a serious suggestion, the paper was a subtle dig at what is often referred to as the “medical model” of mental health. According to this model, certain emotional and behavioural experiences are best conceptualised as illnesses of the mind, akin to illnesses of the body. Further, it is assumed that when these experiences (“symptoms”) cluster together, this indicates the presence of an underlying syndrome or disorder. A diagnostic system should allow doctors to identify disorders by comparing the experiences reported by their patients to checklists of symptoms grouped by diagnosis. The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) is an on-going project that represents the best efforts of the psychiatric profession to operationalise this model, by specifying the range of mental disorders and their associated symptoms.

Bentall argued that happiness could logically qualify as a mental disorder according to the operating assumptions of the DSM. His intention in making this – prima facie absurd – claim was to draw attention to what he perceived as a sleight of hand. The disorders specified in the DSM were presented as “natural disease entities” (Pilgrim & Bentall, 1999, p. 261) that had been objectively and scientifically identified; yet, the decision as to which emotional and behavioural experiences should be regarded as “disordered” in the first place relied on a tacit, subjective, and socially embedded idea of “normality.” The contrast with happiness was intended to bring this point into relief. If happiness could satisfy the same operational criteria that are used to justify the existence of other psychiatric diagnoses, then surely common sense suggested that something had gone awry.

Although much water has passed under the bridge since its publication, Bentall’s paper remains an enjoyable and provocative read and raises fundamental concerns – still very much the subject of argument today – over the validity of psychiatric diagnoses (for some more recent discussion see, e.g., Cromby, Harper, & Reavey, 2013; Johnstone, 2014; Kinderman, Read, Moncrieff, & Bentall, 2013). The DSM has always been controversial, yet when the fifth edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; henceforth DSM-5) was released in May 2013, it met an unprecedented storm of criticism. Self-described anti-psychiatry and mental health service survivor groups were predictably and understandably trenchant in their objections. This time, however, concerns about the DSM project were not limited to those who might be thought of as the usual suspects, but were also voiced by mainstream figures and institutions.

Three such criticisms were particularly prominent, widely discussed, and, to many, surprising. The first came from the eminent psychiatrist Allen Frances, who led the academic group that published the fourth edition of the DSM (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) and became a vocal opponent of the new edition. His concerns were well summed up in the title of his book Saving Normal: An Insider’s Revolt Against Out-of-Control Psychiatric Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life (Frances, 2013). Both here and in numerous online articles, Frances took the authors of DSM-5 to task for loosening the criteria for diagnosing mental disorders, suggesting that they may have been partially influenced in doing so by lobbyists funded by the pharmaceutical industry.1

A second argument was made by Thomas Insel, Director of the United States’ National Institute of Mental Health (Insel, 2013). Whereas Frances defended the basic framework of the DSM, Insel suggested that because psychiatric diagnoses perform so poorly in terms of discriminant validity, their underlying conceptual basis was called into question. Further, he suggested that their use had actually hampered rather than helped research efforts to identify underlying causes for mental health problems.

A third criticism was highlighted by the Division of Clinical Psychology of the British Psychological Society in a statement (2013) on the “classification of behaviour and experience in relation to functional psychiatric diagnoses,” released to coincide with the publication of DSM-5. As well as making similar arguments to Frances and Insel, the statement emphasised the potentially negative impacts of mental illness diagnoses for those receiving them. In particular, it argued that framing emotional and behavioural difficulties as medical issues situates them within the individual, which, in turn, de-emphasises the role of social and material factors and leads to increased stigma.

What do these debates have to do with positive psychology? After all, an explicit goal of the movement, as laid out by Martin Seligman during his tenure as President of the American Psychological Association, was to shift the focus of research efforts away from mental health problems and towards understanding what makes life go well. In an article that has been much-cited in the subsequent literature, Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000) introduced a special positive psychology edition of the association’s flagship journal, American Psychologist. In this paper they set out the case for positive psychology, describing, for instance, how psychology “has, since World War 2, become a science largely about healing. It concentrates on repairing damage within a disease model of human functioning” (p. 5), and claiming that “[w]e [psychologists] came to see ourselves as a mere sub-field of the health professions, and we became a victimology” (p. 6).

In the time since Seligman brought these ideas to wider attention, there has been a striking groundswell of interest not only from psychologists, but also economists, sociologists, and others, in studying psychological constructs such as happiness, wellbeing, hope, strengths, flourishing, and more. Within psychology, in particular, much of this effort has taken place explicitly under the rubric of “positive psychology” and thus is strongly associated with the burgeoning movement set out by Seligman. (Although in fact some of the most significant and influential thinking precedes the instigation of positive psychology as a recognisable movement; see, e.g., Froh, 2004.)

If Bentall’s paper was intended to critique the state of psychiatric practice, a reader versed in the recent development of positive psychology might enjoy a wry smile for different reasons. The joke (and, indeed, the argumentative thrust) of the paper hinges precisely on the implicit absurdity of trying to “diagnose” happiness. It remains true, to my knowledge, that there have been no serious suggestions that happiness should be considered a disorder, in the sense of being undesirable, maladaptive, or requiring some kind of clinical intervention in order that it should be reduced or managed. However, there have been several notable efforts to define and, crucially, measure what it is to be mentally “healthy” over and above merely not being mentally “ill”; to develop, in other words, the conceptual and practical tools to reliably identify and quantify states of happiness. In some cases, these efforts have extended into the realm of classification, with the production of typologies purporting to describe in scientific terms aspects of psychological strength and character (e.g., Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Moreover, as we shall explore in the next section, some of these efforts have borrowed liberally and – I will argue – somewhat unreflectively from the DSM framework.

Above, I outlined three arguments that critics have levelled against the DSM in relation to its use in clinical settings. In the following sections, I want to consider each of these criticisms in more detail and relate them specifically to efforts within positive psychology to develop diagnostic accounts of positive mental health states. Because this is a short chapter, I will focus most attention on two such efforts: Keyes (2002) and Huppert and So (2013). These are not the only examples in the literature but, albeit in different ways, both use the DSM model explicitly as an archetype in their efforts to operationalise the positive psychology concept of “flourishing,” and as such provide a useful illustration of the difficulties that ensue.

Taking this approach inevitably requires a degree of selective quotation and interpretation on my part. This has its risks, not least that my reading might come across as uncharitable, nitpicking, or in other respects unfair. I should emphasise, then, that my comments are in no way intended as a critique of the intentions of the authors – indeed, I take them to share with me an interest in broadening our understanding of mental health beyond the narrow constraints of the medical illness model. My question is instead: Is this interest best served by working within the diagnostic framework and trying to expand it outwards? Or is it the case, to borrow Audre Lorde’s (1984) famous phrase, that “the master’s tools will never demolish the master’s house”?

Systems of clinical diagnosis, by definition, create distinctions between groups of people: those who have the condition in question, and those who do not. Viewed in one way, diagnosis is merely a form of classification, and classification per se is hardly a controversial idea. Evidently we classify objects, animals, people, experiences, and more all the time – some would argue that carving the world up into types of things is fundamental to human cognition (Harnad, 2005). But the actual labels that we ascribe to different classes or categories of things are not neutral. Rather, they have social meanings and, as a result, tangible consequences for their recipients. Think of the historical significance of particular racial categories – the implications, for instance, of living in Germany in the early 1930s and being classified as Jewish.

So it is with a diagnosis. Giving someone a medical label is not an objective, value-neutral, purely scientific act, because medical labels themselves have a social meaning. In the West, medicine is a highly regarded branch of science, and is widely thought (rightly or wrongly) to deal in objective truths. If a doctor tells you that you have an illness, you are likely to understand this not simply as a matter of opinion with which you are at liberty to disagree, but as a fact about the world and, crucially, about you. Moreover, a medical label may impact on how others view you. Perhaps, for instance, people will offer more sympathy if your illness is generally believed to be the result of bad luck, and less if your diagnosis is a “lifestyle” illness widely thought to have resulted from choices you made.

A good example of these social processes in the mental health field is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Even though it had been known for many years that exposure to highly traumatic events sometimes led to lasting difficulties (high anxiety, persistent nightmares, frightening memories or “flashbacks,” somatic symptoms, and so on), the diagnosis of PTSD was only coined in the late 1970s and added to the DSM in 1980. This, Summerfield (2001) argued, was not for scientific reasons but to address a social problem – that of American soldiers returning from the unpopular Vietnam War. Many of these (mostly) men suffered difficulties reintegrating into society; however, because of the prevailing anti-war sentiment, they received not compassion but vilification from an unsympathetic public who regarded them as culpable for their own distress. Giving their difficulties a medical label was intended to effect a shift in perception: “Vietnam veterans were to be seen not as perpetrators or offenders but as people traumatised by roles thrust on them by the US military. Post-traumatic stress disorder legitimised their ‘victimhood,’ gave them moral exculpation” (Summerfield, 2001, p. 95). Whether or not this effort was successful is another question. The wider point is that society “confers on doctors the power to award disease status and the social advantages attached to the sick role” (Summerfield, 2001, p. 98). In other words, giving someone a medical diagnosis is a powerful social signal that has real consequences for how they are thought about by others, how they think about themselves, and what resources they can and cannot access.

As noted earlier, Frances (2013) criticised the DSM-5 for relaxing the criteria for many of the most common mental health diagnoses, such that a larger number of people could potentially meet diagnostic thresholds. The result, he argued, was the “medicalisation” of ordinary life. Difficult or challenging experiences that would previously have been regarded as falling within the realm of normal functioning could now be considered evidence of medical disorder. For example, in the previous iteration of the DSM a diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder could not be given to a person who had been recently bereaved, on the grounds that many of the characteristic symptoms – very low mood, loss of motivation, and so on – were considered normal reactions to the death of a loved one. In the lead-up to the release of the DSM-5, however, it was proposed that the so-called grief exclusion should be removed from the criteria, leading another critic, Wakefield (2011), to note that “It is a serious matter to propose newly classifying millions of people as psychiatrically disordered who are currently considered normally distressed. It places the very credibility of psychiatry on the line” (p. 208).

Despite considerable controversy, when the DSM-5 was published the grief exclusion was indeed removed. At the time of writing, it is too early to tell if the number of people diagnosed with major depression has increased as a result, but it is not hard to imagine how this might happen. Indeed, it is difficult to see how the change could have any other consequence. If being diagnosed with a mental disorder were simply a value-neutral, objective act of classification, then this might not be anything to worry about. But, as argued above, in our society having a mental health diagnosis is highly symbolic. It is widely taken to mean that there is something wrong with you, some kind of dysfunction. Moreover, it gives warrant to the idea that the dysfunction needs to be corrected or treated with a medical intervention. The chief concern of Frances and others was that expanding the scope of the diagnosis of major depression would serve as a licence to pharmaceutical companies to push for more widespread take-up of antidepressant medication.

Returning to positive psychology, is it far-fetched to worry that “diagnosing” positive states could have a similar impact? Evidently, as Bentall (1992) implied, it would be bizarre to regard people who meet Keyes’s (2002), or Huppert and So’s (2013) diagnostic criteria for flourishing as having something wrong with them. But the danger of trying to introduce a new classificatory category for people whose psychological functioning is presumed to be in some way optimal or ideal is that it leads inescapably to an enormous expansion of the category of “dysfunction.” The existence of an apparently scientific, objective, empirically established category of optimum mental health immediately suggests that many people’s – in fact, as a matter of definition, most people’s – mental health is less then optimum. For example, Keyes (2002) wrote:

In short, mental health is not merely the absence of mental illness; it is not simply the presence of high levels of subjective well-being. Mental health is best viewed as a complete state consisting of the presence and the absence of mental illness and mental health symptoms…. Adults with incomplete mental health are languishing in life with low well-being.

(p. 210; emphasis in original)

If mental health is a “complete state,” who would want to be “incomplete”? Again, this is not a neutral exercise in classification but a significant social move. At a stroke, Keyes created a new category of people who, whilst not “ill,” were nevertheless, in the eyes of science, impaired.

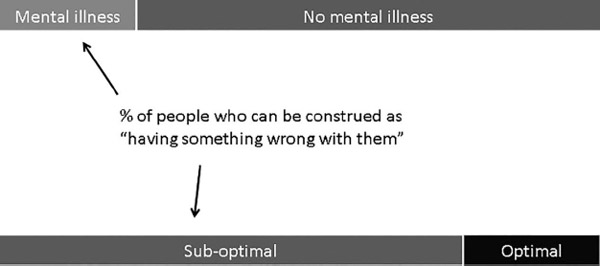

We can visualise this as in Figure 5.1. Imagine that the bars represent some population of people. In the first case (the bar on the top), we have a situation in which a significant but relatively small proportion of people meet criteria for the diagnosis of a mental illness. The worry of Frances (2013) and others was that this proportion had been growing over time, not because of a genuine increase in levels of distress, but because of relaxation of the diagnostic criteria themselves.

The second bar divides the same population a different way – those whose mental health is defined as “optimal” and those whose mental health is not. The actual definition of optimal that is used – Keyes’s, Huppert and So’s, Peterson and Seligman’s, or someone else’s – is less important here than the fact of the distinction having been made authoritatively, and with the powerful rhetoric of “science” in support.

If we think about diagnostic labels – whether of illness or flourishing – as warranting certain forms of action, then we can see a clear commonality between the two cases. In both, there is a category of people who can be construed as “having something wrong with them,” and therefore for whom some form of intervention or treatment might be seen as appropriate. Evidently, however, the group is very much larger in the case where positive mental health can be “diagnosed.”

Just as Frances (2013) worried that the expansion of DSM categories into “normal” experiences would lead to increased use of unnecessary treatment, I have a similar concern that defining positive mental health in this diagnostic way opens the door to those whose business it is to profit from psychological misery, broadly construed. Think, for instance, of how readily the self-help sector has leapt upon the claims of positive psychology. A striking feature of the positive psychology movement is that many of its leading figures have, in very short order, produced books firmly aimed at the popular psychology/self-help market (e.g., Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2008; Fredrickson, 2009; Lyubomirsky, 2008; Seligman, 2002, 2011), often with glossy associated websites and glamorous PR photos. Perhaps this rush to popular publication simply reflects practitioners’ excitement at spreading the word about positive psychology. To my reading, however, these books and websites often seem to encourage readers both to conceptualise their experiences in what are essentially medical terms, and to indulge in self-diagnosis within those terms. The website www.positivityratio.com, for example, is owned by Barbara Fredrickson, a well-known and influential researcher within the positive psychology community. On the front page of the site is a box that says the following:

80% of Americans fall short of the 3-to-1 positivity ratio that predicts flourishing. Click here to take Barb’s [Fredrickson’s] 2-minute on-line quiz and see how you score.

Meanwhile, Seligman has a website at www.authentichappiness.sas.upenn.edu/home, named after one of his popular books and containing a wealth of questionnaires, tools, and other material explicitly branded as positive psychology. The front page has the following invitation:

Feeling Blue? Take a Facebook quiz to get your personal depression score and a set of depression-related words you use in your social-media status updates.

The underlying message of these and other websites is unmistakeable. Feeling a little down today? Now we can use a scientific test to tell you whether you are as happy as you thought you were. And guess what? You’re not. You could be flourishing but you’re languishing, your mental health is incomplete and sub-optimal, the ratio of your emotions is all wrong. You need to do something about that! And by a stroke of luck, we have the solution right here, at the bargain price of …

Perhaps I am too cynical, but I worry about the possible consequences of this message. Given that the production line of new psychiatric medication has been stalled for some years, it is hardly a great leap of imagination to suggest that pharmaceutical companies might look upon developments in positive psychology with interest. It has already been widely claimed that the pharmaceutical industry had a significant influence on the decision to broaden diagnostic criteria in DSM-5, and in lobbying for the increased use of what were once marginal diagnoses that attract pharmacological intervention. How long before we begin to see drugs marketed to treat languishing? By framing positive mental health in the terms described above, there is a risk of imposing a medical understanding, and medical solutions, on areas of human experience that – in my view – should not be within the medical remit at all.

As noted above, when DSM-5 was released Thomas Insel of the NIMH gave voice to a different and, in some respects, more fundamental concern. Where Frances (2013) saw the DSM framework as basically sound, albeit overreaching, Insel cast doubt on the whole enterprise. Highlighting the failure of researchers to identify reliable biomarkers (that is, associated biological signs) for any major category of mental illness, Insel criticised the lack of validity of DSM diagnoses and argued that their use had actually hampered efforts to understand mental health problems.

To see Insel’s point, consider the process of making classifications. All that is required are names for the classes in question, some criteria describing their characteristics, and a reliable method for sorting items, such as objects or people, into them. But does the fact that a classification scheme exists and is reliable mean that it reflects something true and significant about the natural world? The answer is no, and to see why this is so imagine that we wished to develop a classificatory system for identifying witches.2 We might come up with some criteria – pointy hat, crooked nose, evil cackle, broomstick, and so on – that would allow us to identify and sort people into the category of “witch.” It is likely, in fact, that we could do this very reliably, in the sense that different people could use the criteria and come to the same conclusions about who is a “witch” and who is not. But would high reliability at classifying “witches” mean that we had identified a naturally occurring category – that we had discovered people who in some fundamental, naturalistic sense, really are witches? It would not, because the category “witch” has entirely social origins: it is socially constructed. The question of whether or not witches and witchcraft are natural kinds cannot be answered objectively by pointing out how accurately “witches” can be identified according to our criteria.

It turns out that many mental illness diagnoses are not even especially reliable. Different mental health practitioners often disagree about which diagnosis to give a patient even when using exactly the same criteria, which frequently means that people end up labelled with multiple diagnoses (Kessler et al., 2005). However, a deeper problem, at least according to a longstanding and pervasive line of critique, is that diagnostic categories are both socially constructed and invalid. According to this view, the classifications created by the DSM do not reflect objective differences in the world, but are more like categories such as “witch.” Insel’s case against the DSM was that by mistakenly assuming that putative categories such as “depression” or “schizophrenia” reflected real underlying illnesses with biological correlates, researchers had been misled into searching vainly for common characteristics amongst groups of people who may not, in fact, share any. Indeed, as the checklists of symptoms have become longer and more complex in an effort to better capture the range of clinical presentations, the problem of heterogeneity within diagnostic categories has only grown worse. A recent paper pointed out that, within the framework set out in the DSM-5, there are 636,120 possible combinations of symptoms that could lead to the diagnosis of PTSD (Galatzer-Levy & Bryant, 2013). Hardly surprising, then, if it turns out that many people sharing a diagnosis of PTSD have little else in common.

Much of the criticism levelled at diagnostic accounts of mental illness is that psychiatric diagnoses have little basis in the natural world; that is, there is no “real” condition of, say, Bipolar Affective Disorder, only a cluster of symptoms that appear to covary to some extent in the population. Ascribing the label “Bipolar” to someone on the basis of a checklist of symptoms has the rhetorical effect of making it seem as if an underlying disease has been identified. In fact, no explanatory work is being done. The word “Bipolar” is literally, and no more than, shorthand for a set of observations of behaviour. It says absolutely nothing about aetiology – that is, about the cause of a person’s difficulties.

It is important to be clear on the following point: the suggestion that mental health diagnoses are social constructs in no way denies that people experience (sometimes very serious) distress, that this distress may lead to considerable problems in living, and that a variety of forms of treatment may be helpful, including medication. However, it highlights what is perhaps the most significant difficulty for the diagnostic account of mental disorder: establishing what should constitute “disorder” in the first place. The central point in Bentall’s (1992) paper is that the decision to label certain kinds of experiences and behaviours as evidence of pathology or illness is determined by social values. The reason we do not consider happiness to be a psychiatric disorder is nothing to do with science, and everything to do with the norms of behaviour that govern social life at a particular time and place. If, somehow, social norms were to shift such that too much happiness was widely considered undesirable, then it is completely feasible that a diagnosis of “Excessive Happiness Disorder” could be coined. An oft-discussed example of the same kind of process is the way that homosexuality was once considered a mental disorder, diagnosed according to criteria published in an earlier iteration of the DSM. As social attitudes to homosexuality changed, so it increasingly seemed unacceptable to frame it as a medical “problem” that needed to be treated and, eventually, it was removed from the diagnostic manual altogether (see Sadler, 2005).

If mental illness categories are socially constructed, a difficulty arises for researchers wishing to identify the “reality” of mental disorder. Appeals to biology do nothing to solve the problem. As Kinderman (2014) noted, neurobiological processes are involved in the production of all psychological phenomena; but “[b]ecause every thought must involve a neurological process, merely finding a neurological correlate of emotional distress … isn’t the same as identifying a pathology or an ‘illness’ ” (p. 43), since the concept of “illness” is itself socially constructed. Bolton (2008) made a similar argument in his book What is Mental Disorder?, in which he provided a rigorous philosophical analysis of the possible ways in which the concept of disorder could be understood. His conclusion was that the social comparative aspect is simply inescapable – there must be some socially agreed concept of “ordered” behaviour for the concept of disorder to hold meaning. The psychiatrist Pat Bracken (2014) argued that “interpretation and ‘making sense’ of the personal struggles of our patients are to psychiatry what operating skills and techniques are to the surgeon” (p. 242), advocating that psychiatry reject the diagnostic approach entirely and, with it, the effort to conceptualise mental difficulties as akin to illnesses.

Let us again return to positive psychology, where exactly the same difficulties beset the researcher who wishes to define and classify states of positive mental health. Decisions must be made as to what kinds of behaviours and experiences should count as indications that a person is mentally healthy. But on what basis? Keyes (2002) addressed the problem by situating his understanding of mental health in a line of thinking stretching back through the pioneering work of Ryff (1989) and Jahoda (1958), in which “mental health is more than the presence or absence of emotional states” and includes “the presence and absence of positive functioning in life” (Keyes, 2002, p. 208). This sounds reasonable at first glance, but it does not help overcome the problem of normativity. What counts as “positive functioning”? How would we know it if we saw it? Keyes elaborated:

That is, individuals are functioning well when they like most parts of themselves, have warm and trusting relationships, see themselves developing into better people, have a direction in life, are able to shape their environments to satisfy their needs, and have a degree of self-determination.

(Keyes, 2002, pp. 208–209)

Again, this sounds compelling enough until we subject it to a little more reflection. What does it mean to “like most parts” of oneself? Or to develop into a “better” person – better than what, according to whom? What is “direction in life” and who gets to decide whether this is a good thing? Keyes did not say, but appealed to the reliability of the underlying measures as justification of their legitimacy: “The psychological well-being scales are well-validated and reliable (Ryff, 1989), and the six factor structure has been confirmed in a large and representative sample of US adults” (p. 209). However, as the example of classifying witches tells us, reliability is no defence against the charge that the categories themselves are socially constructed.

The fact that Keyes was describing, as it were, mental order rather than disorder does not make the problem of normativity any less acute. Arguably, in fact, it makes it worse. At least, one might argue, there is some broad consensus in society over what kinds of behaviours should be considered problematic and taken as evidence of difficulty. Most people would probably agree, for example, that feeling so low in mood that one cannot get out of bed is a problem (even if they would not necessarily agree that it is best conceptualised as a medical problem). It is not clear to me whether such agreement exists over indications of positive mental health but, if it does, Keyes did not point to any evidence. Rather, his criteria for flourishing were presented from a third person, God’s eye perspective as if they were obvious, uncontroversial, and objectively true. Keyes offered little in the way of critical reflection, nor did he “reflect upon [his] own standpoint in relation to the phenomenon that [he is] studying and attempt to identify the ways in which such a standpoint has shaped the research process and findings” (Willig, 2008, p. 6).

This lack of overt reflexivity is perhaps unsurprising, insofar as that Keyes was working within a tradition of positivistic scientific writing in which the first person perspective is generally discouraged. But just as the dispassionate medical language of the DSM invites us to conclude that diagnostic categories such as “schizophrenia” reflect real illness states that exist in the world independent of our observations, so it is difficult to read Keyes without feeling as if a similar appeal is being made for the states of “flourishing” and “languishing.”

Like Keyes (2002), Huppert and So (2013) also attempted to develop a categorical definition of flourishing based on the DSM architecture. However, their approach to the problem of normativity was yet more problematic. Whereas Keyes based his framework on a model of positive mental health for which there was at least some kind of independent empirical support, Huppert and So simply took the criteria for depression and anxiety listed in the DSM, identified an “opposite” concept, and then mapped these as closely as possible to items contained within the European Social Survey. This approach assumed, for a start, that the DSM categories of depression and anxiety were themselves valid and useful constructs, and moreover that it was reasonable to conceptualise positive mental health as literally the opposite of mental health difficulty. But Huppert and So introduced considerable further subjectivity into the process. How was the list of opposite (i.e., positive) concepts developed? “[A] panel of four individuals (three psychologists and one lay person) began expressing in simple English the words or phrases which best seemed to capture the positive pole of each symptom” (p. 841). This method was described later in the paper as “a systematic examination of the symptoms of the common mental disorders … as described by two internationally agreed sets of diagnostic criteria” (p. 849). Whatever the merits of this approach, I find it a stretch to describe it as “systematic.” Rather, just as with Keyes’s description of his approach to defining flourishing, I am struck both by the appeal to scientific authority and the lack of reflexivity. Who were these four people whose opinions about positive mental health were privileged? Why them? How might their different biographies and socio-cultural experiences have influenced their thinking? Huppert and So (2013) were aware of the problem of subjectivity, but rather than explore the implications, sought instead to downplay it: “While our choice of terms contains some element of subjective judgments, this was essentially a deductive exercise; we had no preconceptions about the nature and number of constructs which we would find” (p. 849; emphasis added). The idea that anyone – let alone three psychologists, presumably well-versed in the associated literature – could approach such a task without any preconceptions rather strains credulity.

To summarise, the underlying problem here is that, just like categories of mental illness, positive mental health states such as flourishing are social constructs and as such are irreducibly normative. Positive mental health is not a natural property of the world waiting to be discovered by psychologists wielding psychometric instruments. Any attempts to define mental health “objectively” lead only to more subjective terms, precisely because there are no objective benchmarks. This does not mean that nothing useful can be said about what it is to feel good, to do well, and so on. But such concepts make sense only in relation to wider social ideas that are dominant within a particular time and place, and they must be situated as such.

Of particular significance is the question of who gets to decide what constitutes mental health. A consistent critique made by the psychiatric survivor movement is what Cromby et al. (2013) called “loss of personal meaning” (p. 110) – the way in which diagnostic systems serve to enforce a particular understanding of experiences which may be at odds with the meaning that they hold for individuals. It is interesting to consider this in the context of Watters’s (2010) argument, concerning how the Western medical model has increasingly come to dominate international discourse about mental illness. In Watters’s telling, distress is a universal fact of life, but the ways in which it manifests behaviourally vary from culture to culture, in accordance with socially available ideas. Watters documented a number of examples from non-Western countries in which, he argued, the Anglo-American model of mental illness had become so prominent in social discourse that it had actually begun to influence the patterns of symptoms people experience – that is, the ways in which people “went mad” were increasingly in accordance with the expectations of the DSM.

If Watters’s (2010) argument is correct, it raises the question: Could positive psychology, in an effort to present to the world a value-free science of wellbeing, in fact end up homogenising expressions of happiness by imposing assumptions about how it should be conceptualised and – crucially – expressed? I do not think this is as far-fetched at it might at first appear. Consider, for instance, the proliferation of international surveys comparing levels of “happiness” (or related constructs) across nations. Insofar as these surveys operationalise happiness according to a Western, largely Anglo-American understanding, they effectively foist this understanding on everyone else as if the experience of positive mental health were the same the world over. If you are not happy like we are, the surveys imply, then you are not happy at all.

As noted earlier, a third significant strand of criticism of the DSM-5 was highlighted by the Division of Clinical Psychology (DCP) of the British Psychological Society. In their position paper, the DCP raised a number of similar concerns to those expressed by other commentators regarding the lack of reliability and questionable underlying validity of constructs. However, they also pointed to the continued presence of stigma against people with a mental health diagnosis, and argued that the medical, diagnostic model of mental health had actually served to increase rather than decrease stigma.

Historically, the kinds of problems that are now seen as “mental disorders” were often trivialised and demeaned. People who experienced serious difficulties of mood and behaviour were thought of as lacking willpower or moral fibre, accused of being “weak-minded,” told to pull themselves together, or dismissed as beyond redemption. Not surprisingly, experiencing this kind of reaction from others often reinforced people’s own negative self-perception, increasing their social isolation and making their problems worse.

In an effort to challenge mental health stigma, recent decades have seen a concerted effort to widen public awareness of the medical model. Slogans along the lines of “no health without mental health” and “mental illness is illness like any other” have become commonplace. The underlying idea is that if the public at large can be persuaded to think of mental health problems as equivalent to physical illness – that is, as caused by an actual dysfunction of the body that can be treated, rather than a failure of character – then this will lead to less stigma. After all, on the whole (and with the caveats referred to earlier regarding so-called lifestyle illnesses) people who become physically unwell are regarded with sympathy and understanding, not dismissed, ridiculed, or blamed.

As a hypothesis this seems plausible prima facie, but contrary to expectations it seems that describing psychological distress and problems of living as medical illnesses has essentially the opposite effect. Read, Haslam, Sayce, and Davies (2006), for example, reviewed this literature and found that biomedical explanations of mental health problems were consistently associated with more stigmatising attitudes (e.g., perceptions of dangerousness and fear) than were psychosocial explanations.

One reason for this may be that framing mental health problems as equivalent to physical illnesses situates the “problem” within the individual. If we are told that a person has unusual and paranoid beliefs because of “a brain disease called schizophrenia” then this seems inexplicable, and perhaps a little scary – which, in turn, has the effect of reinforcing a potentially stigmatising us-and-them dynamic. If we are told that the same person has experienced years of terrifying sexual abuse, and now finds it very difficult to trust other people to the extent of having extreme fears about what they might do (“paranoia”), then our reaction may be different.

What could be the negative consequences of “diagnosing” positive mental health states? Individuals who meet Keyes’s (2002) or Huppert and So’s (2013) criteria for a diagnosis of “flourishing” are unlikely to feel themselves stigmatised and prejudiced against. Their status as flourishers will not lead to the removal of their liberty, to forced medication with psychotropic drugs, to social isolation, or to any of the other violations and indignities that can ensue from a diagnosis of mental illness.

But what of people whose mental health is understood to be sub-optimal – those who are “languishing”? The risk, I think, is that describing positive mental states in categorical, diagnostic terms has essentially the same effect as describing distress as illness. That is, it situates the “problem” within the individual, and therefore encourages explanations that downplay, or even ignore, the role of wider social and systemic factors.

In the UK we have begun to see worrying examples of how this might happen in practice. At the time of writing, for instance, there has been a lively and growing debate about the role of psychology in the welfare and benefits system. Friedli and Stearn (2015) argued very cogently that positive psychology had been co-opted by political forces that, for ideological reasons, would prefer to frame recipients of state benefits as personally responsible for their difficulties, rather than allow them to be seen as victims of socioeconomic circumstances beyond their control. Analysing the content of a government-funded programme targeted at job-seekers, they noted how

[t]he roll-call of valued characteristics familiar from positive psychology, the wellbeing industry and public health – “confidence, optimism, self-efficacy, aspiration” – are imposed in and through programmes of mandatory training and job preparation. They also feature centrally in the way in which people receiving benefits frame their own experiences.

(p. 42)

The idea that vulnerable people might be forced to undertake positive psychology-inspired training in order to receive welfare benefits is surely a long way from what most researchers in the field had in mind when setting out to define positive mental health. But it is easy enough to see, I think, how a medicalised conception of positive mental health states facilitates this kind of application.

Since its inception, some of positive psychology’s leading proponents have seemingly been keen to take an exceptionalist stance. Talk of “business as usual psychology,” “negative psychology,” and so on was common in the movement’s early years. Indeed, this somewhat confrontational tone was highlighted by Lazarus (2003) in a now infamous article questioning whether the positive psychology movement “has legs” (in the sense of having a future qua a discrete and identifiable branch of psychology as a whole). Partly in response to pushback from figures such as Lazarus, overt criticism of the “mainstream” has been toned down a little in recent years in the positive psychology literature. Nonetheless, many positive psychologists still trade – metaphorically and, in some cases, literally – on offering something different from the norm.

But to what extent does positive psychology represent a break with, or a continuation of, the psychology that went before? In the paper mentioned earlier, Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000) argued that “What psychologists have learned over fifty years is that the disease model does not move psychology closer to the prevention of serious problems” (p. 7). This, at least from my perspective, was true then and remains true now. Writing optimistically about the potential of positive psychology to offer an alternative to the disease model, Maddux (2008) argued that it should reject “[t]he categorising and pathologising of humans and human experience” (p. 68) and “[t]he assumption that so-called mental disorders exist in individuals rather than in the relationships between the individual and other individuals and the culture at large” (p. 68).

However, as I have argued above, at least some contemporary approaches to defining mental health in fact run the risk of doing precisely these things: that is, creating new boxes in which to place people and their experiences, and describing the boxes in ways that reinforce an individualised and atomised conception of mental health. I find this somewhat ironic, as like many people I was drawn to the early rhetoric of positive psychology precisely because it seemed to offer an alternative to the prevailing medicalisation of mental health. Yet, by cleaving so closely to a way of thinking about mental health that is conceptually indebted to the diagnostic illness model, there is a significant risk of expanding the range of psychological states that can be considered to be in some way sub-optimal and therefore requiring treatment.

In this chapter I have focused on approaches that have tried explicitly to ape the DSM; however, my view is that these examples typify a wider over-willingness in positive psychology to accept, and a failure to reflect upon, the assumptions and methods of the mainstream (that is, medical) approach to mental health. Simply taking the disease model and turning it on its head is not a shortcut to doing the proper foundational work of finding out how people actually think and talk about their experiences of life going well, and trying to situate this talk within a wider sociocultural framework.

1An irony noted by several commentators was that Frances, as head of the DSM-IV group, oversaw by far the largest increase in the number of diagnostic categories in the manual’s history.

2This example is adapted from Cromby et al. (2013), p. 107.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Bentall, R. P. (1992). A proposal to classify happiness as a psychiatric disorder. Journal of Medical Ethics, 18, 94–98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jme.18.2.94

Bolton, D. (2008). What is mental disorder? An essay in philosophy, science, and values. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Bracken, P. (2014). Towards a hermeneutic shift in psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 13, 241–243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/wps.20148

Cromby, J., Harper, D., & Reavey, P. (2013). Psychology, mental health and distress. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

Diener, E., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2008). Happiness: Unlocking the mysteries of psychological wealth. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Division of Clinical Psychology of the British Psychological Society. (2013). Classification of behaviour and experience in relation to functional psychiatric diagnoses: Time for a paradigm shift. Leicester, England: Author.

Frances, A. (2013). Saving normal: An insider’s revolt against out-of-control psychiatric diagnosis, DSM-5, big pharma, and the medicalization of ordinary life. New York, NY: William Morrow.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2009). Positivity: Top-notch research reveals the upward spiral that will change your life. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press.

Friedli, L., & Stearn, R. (2015). Positive affect as coercive strategy: Conditionality, activation and the role of psychology in UK government workfare programmes. Medical Humanities, 41, 40–47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2014-010622

Froh, J. J. (2004). Positive psychology: Truth be told. NYS Psychologist, 16(3), 18–20.

Galatzer-Levy, I. R., & Bryant, R. A. (2013). 636,120 ways to have posttraumatic stress disorder. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8, 651–662. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1745691613504115

Harnad, S. (2005). To cognize is to categorize: Cognition is categorization. In H. Cohen & C. Lefebvre (Eds.), Handbook of categorization in cognitive science (pp. 19–43). Oxford, England: Elsevier.

Huppert, F. A., & So, T. T. C. (2013). Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Social Indicators Research, 110, 837–861. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9966-7

Insel, T. (2013, April 29). Director’s blog: Transforming diagnosis. National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved from www.nimh.nih.gov/about/director/2013/transforming-diagnosis.shtml

Jahoda, M. (1958). Current concepts of positive mental health. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Johnstone, L. (2014). A straight-talking introduction to psychiatric diagnosis. Monmouth, Wales: PCCS Books.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593–602. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43, 207–222. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3090197

Kinderman, P. (2014). A prescription for psychiatry. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kinderman, P., Read, J., Moncrieff, J., & Bentall, R. P. (2013). Drop the language of disorder. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 16, 2–3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/eb2012–100987

Lazarus, R. S. (2003). Does the positive psychology movement have legs? Psychological Inquiry, 14, 93–109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1402_02

Lorde, A. (1984). Sister outsider. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press.

Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). The how of happiness: A scientific approach to getting the life you want. New York, NY: Penguin.

Maddux, J. E. (2008). Positive psychology and the illness ideology: Toward a positive clinical psychology. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57, 54–70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00354.x

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Pilgrim, D., & Bentall, R. P. (1999). The medicalisation of misery: A critical realist analysis of the concept of depression. Journal of Mental Health, 8, 261–274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09638239917427

Read, J., Haslam, N., Sayce, L., & Davies, E. (2006). Prejudice and schizophrenia: A review of the ‘Mental illness is an illness like any other’ approach. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 114, 303–318. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00824.x

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Sadler, J. Z. (2005). Values and psychiatric diagnoses. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York, NY: Free Press.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York, NY: Free Press.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5–14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

Summerfield, D. (2001). The invention of post-traumatic stress disorder and the social usefulness of a psychiatric category. British Medical Journal, 322(7278), 95–98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.322.7278.95

Wakefield, J. C. (2011). Should uncomplicated bereavement-related depression be reclassified as a disorder in the DSM-5? Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 199, 203–208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e31820cd155

Watters, E. (2010). Crazy like us: The globalization of the American psyche. New York, NY: Free Press.

Willig, C. (2008). Introducing qualitative research in psychology. Maidenhead, England: Open University Press.