Daniel T. Gruner and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

Positive psychology currently emphasizes micro-level interventions that provide short-term gains. But to sustain human flourishing, we must better understand how sociopolitical environments shape individual lives. Much (perhaps too much) effort is devoted to studying the results of brief interventions, though the emerging field of positive psychology had recognized that the “third pillar” of the institutional environment can have a more pervasive and potent impact than any intervention psychologists could devise (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). To understand the important role of institutions, this chapter first provides an evolutionary context for the measurement of societal well-being based on the concept of complexity. We then describe an analysis of archival data collected by the European Social Survey (Round 6) from the viewpoint of sociocultural complexity, operationalized as increasing levels of differentiation (measured by political freedom) and integration (measured by social trust). Finally, we discuss how this broad evolutionary context – informed by an empirical framework of societal well-being – provides a critical foundation for moving the science of positive psychology forward by focusing on the broader, macro-level interventions of our lives.

Societal well-being: a brief history

Ever since human communities started to grow beyond tribal aggregations into larger and more populous kingdoms and empires, rulers have tried to gauge how satisfied their subjects were, and if not, what were the causes for their dissatisfaction. Wise rulers, from the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius to the eighth century Caliph of Baghdad Harun al-Rashid, and seven centuries later King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary, understood that much of their power, and the stability of the nation, relied on the well-being of their people. So, they sought as much information as they could from them, including taking long walks in their capital cities while disguised as commoners, in order to find out what the people thought, and felt, about how things were going.

Aristotle was right when he asserted, almost 2400 years ago, that what men and women want more than anything else is happiness; and when they strive for power, money, health, or beauty, it is because they hope that if they reach such goals, they will be happier. The idea that one of the responsibilities of governments should be to increase the level of happiness in the population is much more recent, and began to be considered seriously only after the French Revolution. It was soon discovered after modern democratic governments were established, that if the electorate was unhappy, they tended to blame the party in government, and vote for another one.

This knowledge, however, was not too useful to political leaders, because happiness remained a vague and unattainable goal. Even the founders of the United States of America implied in their writings that the “happiness” governments should be concerned with was little more than the ability to own property and to keep it safe. Only after World War II did social scientists and politicians begin to pay closer attention to happiness, and started considering prerequisites to it that could be considered responsibilities of a good government: Physical health, mental health, education, retirement pensions, product safety, and so on. These were important, necessary advances in the role of government, but as Aristotle would have pointed out, health, education, safety, and so on, do not by themselves provide happiness, although they might be necessary for it.

So what is happiness, really, and what can governments do to cultivate it in the population? By the 1970s, this question began to be seriously investigated by scientists in the United States and Europe. Large-scale surveys were developed to measure how happy different segments of the population were. Many of these studies did not try to measure happiness directly, and used instead the concept of “satisfaction with life.”

Current metrics of well-being

With the advent of modern democracy many things have changed, but governments still depend on the well-being of the people they serve, perhaps more than ever. It is not surprising, therefore, that the practice of public opinion polling has become a powerful tool at least since the mid-twentieth century, first in the United States, then in other democracies around the world. Hand-in-hand with the interest of politicians, various means of surveying the attitudes and values of populations have become of increasing interest to social scientists who want to understand the roots of psychological well-being, not just at the micro level of individuals, but at the macro level of large-scale social systems (Campbell, Converse, & Rogers, 1976; Sorokin, 1962).

Despite the great amount of information produced in the past few generations about what indicators are the most useful to collect and study, there is still a wide divergence of opinion about what constitutes societal well-being (Diener, 2000). At first, obvious candidates were economic achievements such as Gross National Product (GNP), Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and other data reflecting material well-being. Then, measures of longevity and health were added to the equation. In recent years, more subjective measures have been adopted, including life satisfaction and happiness (Diener, 2000; Oishi & Schimmack, 2010). While each of these ways of assessing the well-being of a social system has its value, it is unclear how they are all related. For instance, while economic success – measured by per capita GDP – is correlated with health, longevity, happiness, and life satisfaction (Diener, 2000; Gana et al., 2013; Oishi & Schimmack, 2010; Pressman, Gallagher, & Lopez, 2013), the relationship seems to be due to the fact that nations on the lowest end of the economic productivity scale are also low on desirable outcomes like happiness and health; however, as per capita GDP and personal income rise beyond a certain point, their correlation with indicators of subjective well-being becomes much weaker, or disappears entirely (Easterlin, 1974; Kahneman & Deaton, 2010).

Our question then follows: Is there a criterion one can use to assess the well-being of nations, based on a less obvious, but perhaps more effective metric than sheer financial accomplishment? The candidate for assessment that we propose here is the concept of sociocultural complexity.

Complexity in human systems

From a systems point of view, complexity is usually a positive attribute. A complex ecosystem is one that accommodates a variety of plant and animal life. A complex organism is one that can survive in a variety of environmental conditions. A complex machine is capable of simultaneously performing a variety of tasks. A complex painting stimulates a variety of responses in the viewer. In all of these instances, complexity depends on the internal differentiation of the system, and on the integration of the different parts. For example, a complex family system is one where each member is encouraged and supported to develop his or her personal strengths and interests (corresponding to the dimension of differentiation), yet at the same time each member is committed to the wellbeing of the other members as well (i.e., integration).

Evolutionary biologists have argued that the spread of life-forms over the planet has tended to select increasingly complex species, and the same trend seems to hold for the evolution of social systems and cultural artifacts as well (Dawkins, 1976, 1982). Of course, the existence of a trend that can be discerned in the past does not mean that the same trend will continue indefinitely into the future. At the same time, it would not be wise to ignore a process that has been in effect for such a long time, and has resulted in the kind of achievements that distinguish humans from other biological organisms, and occasionally, make us proud to belong to our species (Csikszentmihalyi, 1993).

But how can complexity be measured in human communities? Confining ourselves to metrics already in existence, it seems that social differentiation can be measured by the amount of freedom that people living in a given community report; this sense of freedom corresponds to a feeling of indeterminacy about the outcome of life that can be affected by one’s own actions and opinions, as opposed to a fatalistic resignation and acceptance of existing conditions. As to the dimension of integration, it could be expressed at the societal level by the amount of trust people feel about the institutions of their communities. Thus a complex social system would be one where individuals report feeling both free and trusting. Importantly, complexity depends on the presence of both dimensions at the same time. Consequently, we argue that freedom without trust results in chaos, and trust without freedom in deindividuated stagnation. In despotic, repressive societies, both freedom and trust are lacking.

Beyond material success

Good governments not only protect individual rights to pursue financial success, but also provide freedom to structure the content of consciousness, provide grounds for optimism and hope in the future, and possibilities for finding enjoyment in the present (Csikszentmihalyi, 2014). Complex social systems, therefore, involve reciprocal relationships between those in positions of political power and common citizens (who, granted, also hold power, but of a less obvious kind often manifested through interests, skills, abilities, and occupations).

Sociologist Emile Durkheim (1893/1964) argued that advanced societies were those in which the workers felt both connected to a larger functioning system and had freedom to deviate from its structure. Our proposed model of sociocultural complexity echoes this “division of labor,” as we too argue that optimally functioning societies provide a sense of belongingness and individuation, which, in turn, are theorized to reduce anomie and alienation. Thus, from Durkheim’s perspective (and ours), systems that allow organic differentiation concomitant with autonomous integration provide a foundation for social solidarity and individual well-being. Indeed, our individual-level decisions exist within the limits of laws that are handed down from civic institutions, and the policies and gatekeepers that drive them forward. Thus, evaluations of our lives are usually made in relation to others that exist within similar cultural and sociopolitical domains; and within those domains, we tend to expect our governments to provide opportunities to pursue that which makes us happy.

Recently, scholars have conducted cross-national comparisons using archival data to analyze correlates of individual and societal well-being (Diener & Chan, 2011; Pressman et al., 2013). Notably, Richard Easterlin (1974) discovered a paradox: Within countries at any given point in time, wealthier people reported being happier than their less wealthy counterparts; but when several countries were compared on GDP and happiness over time, the relationship between rising wealth and happiness was untenable. For example, the average German is likely to be more happy and satisfied with his life than the average Venezuelan who is much poorer; however, the average inhabitants of Singapore or Denmark, who live above the poverty line but are not as affluent as the Germans, might be happier than them. The Easterlin Paradox subsequently spurred an extended discussion, now nearly four decades old, about what might account for this inconsistency, and whether other important societal indicators predict happiness and well-being above and beyond wealth (for an in-depth review see Easterlin, 2005; Hagerty & Veenhoven, 2003; and Stevenson & Wolfers, 2008). Clearly, economic advantage helps: Norway was an average country in terms of happiness among the 29 or so European countries in the 1960s, whereas now, after the discovery of oil deposits in the adjacent North Sea shale, the country has become one of the wealthiest in the world – and one of the happiest.

Research has since found that greater personal incomes are indeed associated with positive emotions and self-reported life satisfaction, but societal economic productivity (i.e., GDP) is a weak predictor of life satisfaction at best, and not associated with fluctuations in emotions (Diener, Tay, & Oishi, 2013). This, perhaps, can be attributed to a widely accepted view that increases in GDP are not commensurate with granular level rises in personal income, but rather, measure national economic production in totality, often neglecting important considerations such as environmental sustainability, social justice, and psychosocial well-being (Diener & Ryan, 2011). Moreover, once basic needs are met, individuals often place attention on more fleeting and hedonic emotional gains from material sources (Csikszentmihalyi, 1999). And while income and GDP have risen in many countries around the world, self-reported happiness remains quite constant (Diener & Ryan, 2011; Myers, 1993). In fact, Oishi and Kesebir (2015) showed that rises in GDP are associated with unequal distributions of wealth in several countries, which in turn account for fluctuations in self-reported well-being. In a seminal study conducted by Kahneman and Deaton (2010), it was reported that increases in household income (log scaled) provided a continuous boost in reflective life satisfaction (i.e., cognitive dimension of subjective well-being), whereas log income was associated with positive emotions (i.e., affective dimension), but only up to approximately US$75,000. Understandably, if one cannot satisfy basic needs such as access to food, water, and adequate healthcare, then it can be difficult to allocate attentional resources to less pressing aspects required for achieving the “good life.” For instance, Pressman et al. (2013) found that low GDP countries (compared with mid or high GDP countries) showed stronger associations between positive emotions and health. This finding perhaps suggests that when needs are unmet, positive emotions take on a critical role in optimal health. Moreover, in a summary of studies, Oishi and Schimmack (2010) suggested that perceived social trust, fairness, and tolerance of others account for substantial variation in the cognitive and affective dimensions of subjective well-being.

Though each of the studies highlighted above undoubtedly make important contributions to our theoretical and empirical understanding of societal well-being, it is becoming difficult to truly understand the role of personal material gains and national economic productivity ceteris paribus. And so, we believe it is important to revisit large national datasets to explore whether a new framework might be tested utilizing our long-standing biological (genetic) and cultural (memetic) conceptions of complexity. Because items capturing freedom and trust have been included in many of the large-scale surveys conducted in the past few decades, it is possible to use existing data to explore whether these measures of complexity tell us something worth knowing about well-being on a societal scale; for instance, whether after controlling for material success, complexity explains differences in the happiness and life satisfaction of the populations involved.

Method

Data preparation

Participants (N = 39,215) from 29 countries (48.6% male, 51.3% female, 0.1% unreported; age range = 15–103; M = 48.19; SD = 18.07) responded to a series of questions administered during the sixth wave of the European Social Survey (ESS-6; European Social Survey, 2012). Individual responses from the ESS-6 were used to explore our theoretical model of sociocultural complexity because of the relatively homogenous representations of geographical areas. We thought this would suit our initial empirical assessment without introducing cross-cultural confounds that often surface in broader samples from around the world. Furthermore, it was in our best interest to capture as many data points from European territories under one dataset as possible. Finally, we expected similar methodological implementation of interview and survey designs across these countries.

The ESS-6 includes nationally representative samples of European nations. Sampling frames in the ESS-6 included simple random and stratified random sampling by geographic location, accounting for population proportion and assuring representation of both urban and rural areas. For the present analyses, we used a subset of complete cases within the ESS 2.1 datafile (European Social Survey, 2012). Missing cases were deleted listwise to ensure structural equation models could be processed in AMOS. Design and population weights were applied accordingly when constructing scale composites and running multivariate analyses, including scale reliabilities, simple correlations, and regressions.

Measures

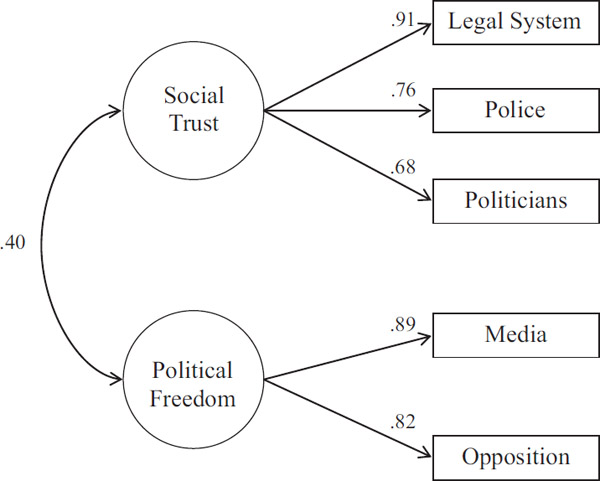

To measure social trust, participants were asked how much they trusted their legal systems, police, and politicians on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (no trust at all) to 10 (complete trust). Political freedom was measured with two items (“opposition parties are free to criticize the government” and “the media are free to criticize the government”), to which participants were asked whether each statement applies in their country on an 11-point scale from 0 (does not apply at all) to 10 (applies completely). Positive affect (PA) was measured with four items asking participants how often during the past week they were happy, enjoyed life, had a lot of energy, and felt calm and peaceful on a 4-point scale from 1 (none, or almost none of the time) to 4 (all, or almost all of the time). Similarly, negative affect (NA) was measured with four items asking participants how often during the past week they felt depressed, lonely, sad, or anxious on a 4-point scale from 1 (none, or almost none of the time) to 4 (all, or almost all of the time). Satisfaction with life (SWL) was measured with a single item (“all things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole nowadays?”) rated on an 11-point scale from 0 (extremely dissatisfied) to 10 (extremely satisfied). Personal income was measured in deciles. Participants reported total net household income from lowest (1st decile) to highest (10th decile) relative to country-specific national currency. Deciles were generated by situating within country median incomes at the top of the 5th decile (European Social Survey, 2012).

Data analytic strategy

Confirmatory factor analysis with SPSS AMOS was employed to examine the latent structures of sociocultural complexity and emotions. Next, Pearson bivariate correlations and hierarchical regressions explored the strength of relationships among variables. Finally, a structural equation model was evaluated in AMOS to examine relationships between complexity, income, positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction.

Several common fit indices were used to evaluate models, including the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), incremental fit index (IFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and goodness of fit index (GFI). The RMSEA accounts for the error of approximation within the population according to degrees of freedom, where values less than .05 are considered acceptable and anything above .10 inadequate. The CFI and IFI compare the default model to the independence model (i.e., worst fitting model). Values on the CFI and IFI range from 0.00 (no improvement; poor fit) to 1.00 (greatest improvement; perfect fit). Anything above .95 is deemed good fit. The GFI is analogous to proportion of variance explained and ranges from 0.00 to 1.00, where higher values indicate better fit (Ho, 2006). The chi-square statistic is also reported, but because it is highly sensitive to sample size, we did not refer to it, or to the chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio, as a metric of model adequacy given the large sample size of the ESS-6.

Results

Sociocultural complexity

First, we specified and evaluated the latent structure of sociocultural complexity. It was hypothesized that three items (legal system, police, politicians) would load on the Social Trust factor, and two items (free media, free opposition) would load on the Political Freedom factor. We further hypothesized that the two factors would be positively correlated (see Figure 24.1). Maximum likelihood estimation substantiated an oblique two-factor solution yielding excellent fit indices, χ2(39,215) = 207.63, df = 4, p < .001, χ2/df = 51.91, RMSEA = .036, 90% CI = .032 − .040, IFI = .99 CFI = .99, GFI = .99. Factor loadings were mid to strong and ranged from .68 to .91 (all p values < .001). The correlation between latent factors was also significant (β = .40). Internal consistency for all five items taken together yielded a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of α = .78. Each latent factor was given a fixed variance of 1.00 to allow model convergence.

Positive and negative emotions

Next, we evaluated the factor analytic structure of positive and negative emotions. It was hypothesized that four items (happy, joyful, energetic, peaceful) would load on the Positive Affect factor, and four items (depressed, lonely, sad, anxious) would load on the Negative Affect factor. We further hypothesized that the two factors would be inversely correlated (see Figure 24.2). Again, maximum likelihood estimation substantiated an oblique 2-factor solution yielding excellent fit indices χ2(39,215) = 1375.34, df = 18, p < .001, χ2/df = 76.41, RMSEA = .044, 90% CI = .042 − .046, IFI = .99 CFI = .99, GFI = .99. Factor loadings were mid to strong and ranged from .59 to .77 across factors (all p values < .001). Latent factors were given a fixed variance of 1.00 to allow model convergence. Findings demonstrate that PA and NA are indeed distinct constructs, and significantly inversely correlated (β = −.68).

Complexity and well-being

Averaging individual responses yielded reliable scale composites for Sociocultural Complexity (Cronbach’s α = .78), Social Trust (α = .80), Political Freedom (α = .86), Positive Affect (α = .76), and Negative Affect (α = .78). Pearson bivariate correlations were conducted to assess relationships among variables. Due to the nature of the large dataset, nearly all correlations were significant at the p < .001 level. In such instances, it is important to examine effect sizes rather than relying on significance testing alone. For example, meaningful associations emerged between sociocultural complexity and negative affect (r = −.24), and sociocultural complexity and life satisfaction (r = .37), while the relationship between complexity and personal income (r = .05) was smaller. However, it is important to note that the correlation between income and life satisfaction (r = .18) was approximately half that of complexity and SWL (r = .37). In turn, PA (r = .39) and NA (r = −.42) were more strongly associated with SWL than personal income, while personal income was slightly correlated with PA (r = .14), and inversely correlated with NA (r = −.16). Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of all variables are summarized in Table 24.1.

Here, a pattern of societal well-being begins to emerge such that the suite of positive and negative emotions and combination of social trust and political freedom (i.e., sociocultural complexity) might better predict life satisfaction than increasing material resources as measured by personal income. A scatterplot of the relationship between sociocultural complexity and life satisfaction can be seen in Figure 24.3. To further explore the relationships among variables, we proceeded to test individual and total contributions to SWL with hierarchical regression, and predictive path estimates with structural equation modeling.

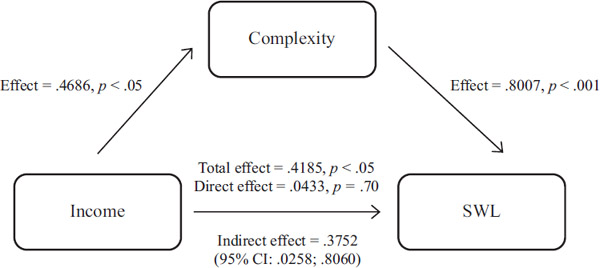

Regression analyses revealed that personal income β = .092, t(39,215) = 21.645, p < .001, complexity β = .284, t(39,215) = 65.526, p < .001, positive affect, β = .225, t(39,215) = 45.639, p < .001, and negative affect, β = −.220, t(39,215) = −43.700, p < .001 accounted for 30% of the total variance in SWL. Regressing SWL on income alone yielded a standardized beta of β = .17, which dropped to β = .092 when other variables were included in separate steps. Given that complexity contributed 13.1% of the variance beyond income, we proceeded to test indirect effects by aggregating individual level data at the population level (N = 29 countries). Bias-corrected bootstrapping with the PROCESS statistical package was employed to offer conservative support beyond limitations of sample size (Hayes, 2013; Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007). The indirect effect of complexity on SWL demonstrated significance (effect = .3752, 95% CI = .0333, .8055) based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples, suggesting that complexity mediates the relationship between income and SWL (see Figure 24.4).

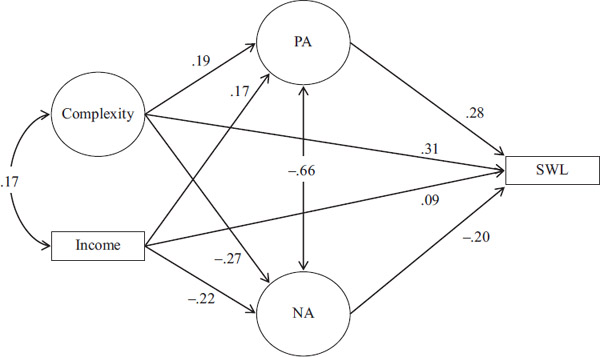

Next, we specified and evaluated a hybrid structural equation model with AMOS using individual responses. Based on bivariate correlations and hierarchical regressions, we hypothesized that sociocultural complexity and personal income would be minimally correlated, but, in turn, would unidirectionally predict both positive and negative emotions, which would also predict SWL. We further hypothesized that positive and negative emotions would be correlated, and that complexity and income would unidirectionally predict SWL (see Figure 24.5).

Maximum likelihood estimation indicated that our model had an excellent fit with the data, χ2(39,215) = 5455.35, df = 81, p < .001, χ2/df = 67.35, RMSEA = .041, 90% CI = .040 – .042, IFI = .98, CFI = .98, GFI = .98. All path estimates presented in Figure 24.5 are significant at the p < .001 level. For each latent factor, one path was fixed with a variance of 1.00 to allow model convergence. Error terms and disturbances in SEM remove measurement error, while revealing the predictive strength of the relationships among variables. Modification indices suggested that two error terms in the political freedom factor should be correlated to improve model fit. Given that these variables corresponded to one of the two sociocultural complexity dimensions, we included the within-factor correlation in the final model.

Discussion

When we evaluate how satisfied we are with our lives, we tend to reflect on past experiences, consider current moods, and contemplate whether we are reaching our goals and aspirations. For some, material success might define a life well lived. For others, high quality social connections are the path to happiness. Still others believe that having the freedom to question the status quo and place trust in elected officials takes precedence. In fact, we argue that each of these conditions provide important contributions to life satisfaction, though some have a more powerful impact than others.

Our findings suggest that in European nations, higher levels of trust in social institutions, coupled with high levels of political freedom, provide a reliable measure of sociocultural complexity, which contributes as much to life satisfaction as the interplay between positive and negative emotions such as happiness, enjoyment, and peacefulness on the one hand, and anxiety, loneliness, and sadness on the other. Importantly, sociocultural complexity contributes more to life satisfaction than higher levels of personal income, indicating the paramount importance of freedom and trust for a satisfying life. The indirect mediating effect of complexity on life satisfaction further suggests that income is associated with perceptions of political freedom and social trust, but it is through complexity rather than income that positive life evaluations are made. Taken together, sociocultural complexity, personal income, and emotions account for substantial variation in positive life evaluations, though emotions and complexity contribute significantly more to life satisfaction than higher incomes.

We do not suggest that freedom, trust, and positive emotions present a mutually exclusive nor exhaustive list of well-being indicators. Moreover, the countries sampled here represent a fairly homogenous subset of European nations. To be sure, positive relationships, physical health, spirituality, education, and socioeconomic status have all been shown to play important roles in subjective well-being (Diener, 2000; Oishi & Schimmack, 2010; Pressman et al., 2013). What we have shown here, rather, is that the evolutionary foundation of differentiation and integration that has supported biological organisms can also be applied to cultural, social, and psychological frameworks. Indeed, sociocultural complexity is a bio-psychosocial process evident across each of the three pillars of positive psychology – emotions, traits, and institutions. In this chapter, we have begun to approximate an important link between variables that transcends micro-level interventions, particularly emphasizing the role of sociopolitical institutions (e.g., media and the judiciary) in the affective and cognitive dimensions of well-being (i.e., emotions and satisfaction with life). Moving forward, it will be important for positive psychology to grasp how the macro interventions of institutions structure domains of individual experience, while we continue to devise useful micro-level interventions for human flourishing, happiness, and well-being.

Positive human development is an iterative cycle of intra- and inter-personal changes and experiences – an ontogenetic relationship between self, others, and social environments (Rathunde & Csikszentmihalyi, 2006). To pursue our best selves, it is important to develop individualized identities and care for our personal well-being, while also maintaining connections to close and distant others such as families, friends, mentors, co-workers, and members of the community broadly conceived. Providing political freedom and establishing social trust allows individuals to feel connected to known and unknown members of their communities, and can generate opportunities for creative exploration and exposure to different perspectives while avoiding the burden of anxiety and loneliness. Complexity also plays an important role in finding opportunities for enjoyment and creativity in daily life. For example, a key component of personal growth is increasing levels of balance between individual skills and the challenges of different activities (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Moreover, highly creative individuals are capable of moving between dualities of human experience, such as idleness and activation and introversion and extraversion (Csikszentmihalyi, 1997). These examples encompass what we have come to understand as psychological complexity. We now add to this literature by offering empirical evidence that sociocultural complexity contributes to both affective (emotions) and cognitive (life satisfaction) dimensions of well-being.

Happiness, joy, peace, and vitality are crucial for positive life evaluations – both momentarily and in retrospect. Our day-to-day emotional experiences impact appraisals of social contexts, and in turn, how we see ourselves in relation to other members of the social system (Csikszentmihalyi, 2014; Diener & Ryan, 2011). A complex social system provides freedom to think critically and reflect on individual values. Relatedly, if people can trust those elected into positions of power to do what is best for the greater good, then perhaps they will be more inclined to think freely and trust the more immediate institutions of their daily lives (e.g., schools, health systems, co-workers, and employers). Trust and freedom can foster a sense of belongingness with the rest of society. In turn, belongingness mitigates loneliness, sadness, anxiety, and depression. Furthermore, if one’s individual values are misaligned with those of the larger social system, opportunities to freely oppose the predominant points of view might boost positive emotions and life satisfaction.

Considering material resources, we agree that it is important to meet basic needs by gaining access to nutritious food and affordable healthcare, though we have not tested these issues here. It is also possible that individual differences will play a role in how members of different income brackets evaluate their lives. For example, households in upper income deciles can indeed afford healthy food and clean water, but societal pressures can also perpetuate a culture of hyper individualism and upward social comparison that adds to anxiety. Hedonic adaptation makes it all too easy to habituate ourselves to certain luxuries, and to want more of what we have, or to desire that which we do not (Helson, 1948). Thus, the wealthy also face threats to their happiness, but often for very different reasons than the absence of resources needed for survival. It will be important for future research to take such issues into account, and to also explore how our model fares when comparing more heterogeneous national samples from other corners of the world, including the Americas.

Moving forward

Positive psychology has made great strides in the last 15 years. It has introduced new avenues for measuring human flourishing, happiness, motivation, and psychosocial well-being (Csikszentmihalyi & Nakamura, 2011). The field has moved beyond remediating psychopathologies and has placed emphasis on sustaining optimal experiences and building positive social contexts across various life domains, including education, leisure, and work. Positive psychology has introduced rigorous, systematic methods to examine the good life, but we must also consider that if we are unable to translate research into actionable change at the policy level, then it will be difficult to make lasting impacts on individuals.

Well-being is a bottom-up and top-down process. On an individual level, we can make efforts to be more mindful, more grateful, and more motivated if we know what our virtues, talents, and skills are. But if the institutional structures and cultural domains in which we exist deprive us of freedom to think, to criticize, and to choose our own path of intellectual curiosity, then individuality will stagnate, and anxiety, sadness, and loneliness will ensue. We urge current and future researchers, practitioners, educators, professionals, and students to use these arguments to drive positive psychology research forward, to apply its findings to help shape policy on a broader scale, and to reflect on understanding how agency and trust can be used against injustices within and across communities. As psychologists, we understand that empirical knowledge builds iteratively, and we must continue to keep within sight the three levels of analysis – those of momentary experience, of individual lives, and of societal institutions – as we move forward.

Concluding remarks

Many reasons have recently been proposed as alternatives to a purely materialistic explanation of happiness, ranging from climate or amount of sunlight, to the size of the gap between the top and bottom quartile in income, to the extent of suffering from war. Here, we suggest that happiness and SWL are most strongly influenced by two social conditions: Do the people feel free to express their opinions? Do they feel that the media report news freely? And the other: Do individuals trust key institutions like the government, the judicial system, and the police?

In this chapter, we have tested a novel framework of societal well-being based on data collected from 29 European nations. We examined the psychological impact of having opportunities to express opinions freely, and of forming trustworthy expectations of sociopolitical institutions. Our model of sociocultural complexity considers perceptions of important institutions such as the legal system, police, politicians, and media, and the freedom to oppose the ideologies of current governing bodies. We argue that the good life is in fact an epiphenomenon of social contexts in which the population can live in freedom and trust. We have shown that complexity – a theoretical derivation from evolutionary theory based on differentiation and integration – may indeed provide a reliable metric worthy of inclusion in current measures of societal well-being beyond material success. In sum, when the “third pillar” generates trust and allows freedom in society, the population reports fewer negative and more positive moods; people report more satisfaction with their lives, even when the material environment is poor. Taking these facts into account suggests new vistas for positive psychology to pursue, for the implementation of large-scale interventions that might have more permanent effects on individual well-being.

References

Campbell, A. P., Converse, P. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life. New York, NY: Russell Sage.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1993). The evolving self. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1999). If we are so rich, why aren’t we happy? American Psychologist, 54, 821–827. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.10.821

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). The politics of consciousness. In T. J. Hämäläinen & J. Michaelson (Eds.), Well-being and beyond: Broadening the public and policy discourse (pp. 271–282). Northampton, MA: Elgar. http://dx.doi.org/10.4337/9781783472901.00020

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Nakamura, J. (2011). Positive psychology: Where did it come from, where is it going? In K. M. Sheldon, T. B. Kashdan, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Designing positive psychology: Taking stock and moving forward (pp. 3–8). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Dawkins, R. (1976). The selfish gene. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Dawkins, R. (1982). The extended phenotype. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55, 34–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34

Diener, E., & Chan, M. Y. (2011). Happy people live longer: Subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 3, 1–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01045

Diener, E., & Ryan, K. (2011). National accounts of well-being for public policy. In S. I. Donaldson, M. Csikszentmihalyi, & J. Nakamura (Eds.), Applied positive psychology: Improving everyday life, health, schools, work, and society (pp. 15–34). New York, NY: Routledge.

Diener, E., Tay, L., & Oishi, S. (2013). Rising income and the subjective well-being of nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 267–276. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0030487

Durkheim, E. (1964). The division of labor in society (G. Simpson, Trans.). New York, NY: Free Press. (Originally published in French as De la division du travail social, 1893)

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? In P. A. David & M. W. Eder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramowitz (pp. 89–125). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Easterlin, R. A. (2005). Diminishing marginal utility of income? Caveat emptor. Social Indicators Research, 70, 243–255. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-004-8393-4

European Social Survey. (2012). ESS6–2012 Data Download. Retrieved from www.europeansocialsurvey.org/data/download.html?r=6

Gana, K., Bailly, N., Saada, Y., Joulain, M., Trouillet, R., Hervé, C., & Alaphilippe, D. (2013). Relationship between life satisfaction and physical health in older adults: A longitudinal test of cross-lagged and simultaneous effects. Health Psychology, 32, 896–904. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0031656

Hagerty, M. R., & Veenhoven, R. (2003). Wealth and happiness revisited: Growing national income does go with greater happiness. Social Indicators Research, 64, 1–27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1024790530822

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Helson, H. (1948). Adaptation-level as a basis for a quantitative theory of frames of reference. Psychological Review, 55, 297–313. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0056721

Ho, R. (2006). Handbook of univariate and multivariate data analysis and interpretation with SPSS. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis.

Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107, 16489–16493. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1011492107

Myers, D. G. (1993). The pursuit of happiness. New York, NY: Avion.

Oishi, S., & Kesebir, S. (2015). Income inequality explains why economic growth does not always translate to an increase in happiness. Psychological Science, 26, 1630–1638. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956797615596713

Oishi, S., & Schimmack, U. (2010). Culture and well-being: A new inquiry into the psychological wealth of nations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 463–471. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1745691610375561

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42, 185–227. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316

Pressman, S. D., Gallagher, M. W., & Lopez, S. J. (2013). Is the emotion–health connection a “first-world problem”? Psychological Science, 24, 544–549. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956797612457382

Rathunde, K., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2006). The developing person: An experiential perspective. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1, Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 465–515). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5–14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

Sorokin, P. (1962). Social and cultural dynamics. New York, NY: Bedminster.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2008). Economic growth and subjective well-being: Reassessing the Easterlin paradox. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1, 1–102. http://dx.doi.org/10.3386/w14282