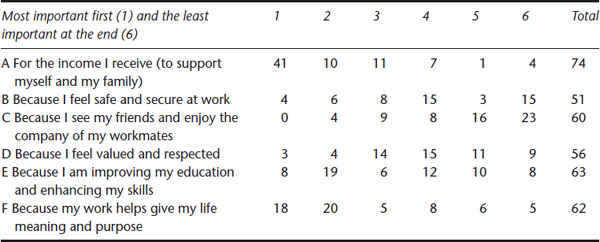

Table 30.3 Responses to the question “Why do you come to work?”

Positive psychology is a modern area of study which explores how and why positive thinking and an optimistic outlook can make a difference to people’s lives and wellbeing. Critics (e.g., Coyne, 2013; Miller, 2008) say it is a luxury which applies only in affluent societies to well-off people. Others think it can apply everywhere. I want to explore how people sustain their resilience and are able not just to cope, but to prosper in situations where things appear stressful, unrewarding, tough, and unfulfilling. In particular, I want to focus on work and employment, where people spend so much of their adult lives. At the end of the chapter, I report on my findings from a small survey of 78 people working in public and private sector occupations in Kabul, Afghanistan, in some of the most testing situations in the world. The way they feel about their work, and their hopes and fears for the future, make for challenging reading.

Positive psychology seeks to understand what it is that gives people – maybe people like me – the determination and inner strength to go on in the face of the overwhelmingly negative evidence which is daily presented to us. I am by nature an optimist and tend to think positively, looking to find solutions to problems rather than allowing problems to burden and overwhelm me. But I also recognise the fact that, in many aspects of my life, there are always loose ends which I never quite manage to get hold of or tie up. Living with uncertainties and with unresolved issues is part of our human existence.

To put it bluntly, despite our dreams of and hopes for a just and loving world where people of different nations, faiths, ethnicities, and cultures can live together peaceably, the evidence suggests that this is always just over the next hill or round the next corner. And the brutality of reality, the sheer overwhelmingness of negative evidence, should be enough to convince us that our deepest longings are unachievable. Add to this the environmental catastrophe awaiting us in the coming century, caused both by human activity and the forces of nature, and the prospects for any positive vision of the future wear rather thin. And yet, we press on, in the hope that a better future can and will be created.

I have long been fascinated by the power of people to do really liberating things – but also to act in ways which are deeply inhuman. The two are inter-woven and can be found not only in the more extreme situations of war and conflict, but in people’s mundane, everyday working lives.

A number of thinkers, philosophers, theologians, psychologists, and occasionally novelists have profoundly influenced my thinking. They have the ability to describe what is, in order to affect what might be.

As a university student in the 1970s, I was fascinated by the mid-twentieth century Chinese “experiment” under Mao Zedong (1893–1976) and intrigued by what he was trying to achieve. I read Edgar Snow’s Red Star over China (1937) and wrestled with The Thoughts of Chairman Mao Tse-Tung (Mao, 1967). Later, I came to understand the huge cost in millions of lives which his experiment entailed, catalogued so graphically by Jung Chang in Wild Swans (1991) and Mao: The Unknown Story (2005).

I read widely, drawing on the ideas of the radical Brazilian educator Paulo Freire (1921–1997) with his emphasis on “praxis” – informed and values-driven action – and “conscientisation,” using literacy as a tool for challenging oppression and helping the poor become the subjects of their own destiny rather than the objects of the decisions of others. His most influential book was Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Freire, 1970).

I remember vividly hearing a Catholic priest describe how Freire’s team spent time in the big city slums, listening to the conversations of the illiterate slum dwellers and, through doing so, identifying the constantly recurring word favela – slum – as a good basis for their literacy campaign. Fa-ve-la became the first word the residents learned to read and write. And, as they did so, the priest noted, their thoughts and ideas no longer became confused or lost but could be retained and developed. And acted on.

The factory owners’ wives, he told us, visited the favelas each year to give Christmas hampers to the wives of their husbands’ employees. One Christmas, after a literacy campaign, the factory owners’ wives were shocked when the favela women refused their gifts. “But your children will go hungry,” they gasped. “It’s Christmas.”

“We don’t want your charity,” the women responded. “We want you to tell your husbands to pay our husbands proper wages.” A real example of positive psychology in action!

But it was the responses to mid-twentieth century Nazism which most intrigued and challenged me.

The German-Jewish philosopher and political theorist Hannah Arendt (1906–1975) mulled over the “banality of evil” in relation to the horrific Second World War crimes of the Nazis and, in particular, the trial and conviction in 1961 of Adolf Eichmann, one of Hitler’s closest henchmen and the architect of the Holocaust. Arendt’s analysis is complex, but an invaluable contribution to social science – her insights being in some ways borne out by the experiments of Yale psychologist Stanley Milgram, described below.

That phrase, the “banality of evil,” has always carried a great sense of foreboding for me. Arendt coined it whilst observing Eichmann’s trial. In her treatise on the “banality of evil,” Arendt demanded a rethink of established ideas about moral responsibility.

The American philosopher Judith Butler wrote that there were at least two challenges to legal judgment that Arendt underscored, and then another to moral philosophy more generally:

The first problem is that of legal intention. Did the courts have to prove that Eichmann intended to commit genocide in order to be convicted of the crime? Her argument was that Eichmann may well have lacked “intentions” insofar as he failed to think about the crime he was committing. She did not think he acted without conscious activity, but she insisted that the term “thinking” had to be reserved for a more reflective mode of rationality…. So if a crime against humanity had become in some sense “banal” it was precisely because it was committed in a daily way, systematically, without being adequately named and opposed … the crime had become … accepted, routinised, and implemented without moral revulsion and political indignation and resistance.

(Butler, 2011, paras. 3–6)

For Arendt, what had become banal was the failure to think.

Just such a mentality pervades the powerful books by Afghan writer Khaled Hosseini. In The Kite Runner (2003), he described the awful “normality” of life in Afghanistan under Taliban rule, the daily atrocities, the cruel abuse of power, the inbuilt injustices of class, tribe, and culture. These themes were further explored and elaborated in his next two books, A Thousand Splendid Suns (2007) and And the Mountains Echoed (2013). More about Afghanistan later.

Butler continued:

Is thinking to be understood as a psychological process or, indeed, something that can be properly described, or is thinking in Arendt’s sense always an exercise of judgment of some kind, and so implicated in a normative practice? If the “I” who thinks is part of a “we” and if the “I” who thinks is committed to sustaining that “we,” how do we understand the relation between “I” and “we” and what specific implications does thinking imply for the norms that govern politics and, especially, the critical relation to positive law?

(Butler, 2011, para. 14)

Arendt described how Eichmann tried to fall back on the philosophy of the eighteenth-century German moral philosopher Immanuel Kant and his deontological principle of the categorical imperative (an unconditional moral law that applies to all rational beings and is independent of any personal motive or desire). Kant argued that, to act in the morally right way, people must act from duty (the Greek word deon means obligation or duty). It is not the consequences that make an action right or wrong, but a person’s motives in carrying out that action. Eichmann attempted to reformulate the categorical imperative to justify his behaviour as absolute obedience (duty) to the will of his Führer, who would himself so act.

Mindful of Eichmann’s trial (which was taking place at the time), the American social psychologist Stanley Milgram began to conduct some important experiments at Yale University. Participants thought they were taking part in a study looking at the effects of punishment on memory. Do people learn better if they are punished every time they make a mistake?

Alex Haslam, Professor of Social and Organisational Psychology at the University of Exeter, described the process:

To help the experimenter investigate this question, participants were placed in the role of teacher and asked to administer an electric shock to a learner every time he recalled the wrong word from a previously learned list of work pairings. The shocks started at 15 volts but increased every time an error was made, going right up to 450 volts – well beyond a point that would be lethal. In fact, the learner was an actor … and the shocks were not real. But the teachers did not know this. Indeed, the question that Milgram was really investigating was how willing the participants would be to go along with the experimenter’s instructions. Would they stop administering shocks at 75 volts (when the learner let out a cry of “Ugh!”) or 150 volts (where he demanded to be let out, because his heart was starting to bother him), or at 300 volts (where he let out an agonized scream and refused to answer any more)? Thinking about it, how far would you go?

(Haslam, 2011, paras. 2–3)

The stunning outcomes of Milgram’s experiments were that 90% of teachers continued beyond the 300 volts point. And 65% continued administering shocks right up to the 450-volt point. Haslam continued:

Milgram’s research is phenomenally important because it shows that normal decent people can engage in acts of extreme cruelty when they are instructed to do so by others. When psychiatrists and members of the public were asked what proportion of people would go to the 450-volt mark they tend to say something like 1% – assuming that only a sadist or a psychopath would go this far. In this, Milgram saw his studies as supporting Hannah Arendt’s notion of the “banality of evil” … This suggests that terrible events like the Holocaust might occur because people were concerned more to do their bureaucratic duty than to question the ends towards which that bureaucracy was working.

(Haslam, 2011, para. 5)

Haslam argued that the Milgram experiments may not be all that they seem, as

participants’ identification with the experimenter and with Milgram’s scientific project was central to their willingness to administer shocks to the learner. Rather than simply obeying orders, participants were thus “working towards the experimenter” – working creatively to do what they thought was right with reference to an identity that centred on their belief in the value of science. This process mirrors that of “working towards the Führer” which the historian Ian Kershaw argues explains the dynamism of the Nazi state and the brutality displayed by its functionaries…. The source of evil is not in the banal workings of passionless bureaucracy, but in the delineated content of a shared identity (a sense of “us” that has no place for “them”), which empowers leaders and mobilises followers.

(Haslam, 2011, paras. 6–9)

Milgram’s findings have not consistently been borne out by experiments in other situations and cultures. His own thinking had been profoundly affected by the German-Jewish social psychologist Erich Fromm, whose seminal book Escape from Freedom (1941) dealt with psychological aspects of social control, delusion, and conformity. Fromm had himself been influenced by the Frankfurt School, or Institute for Social Research, set up by a group of Marxist intellectuals in Germany in 1923, affiliated to the University of Frankfurt and closed down by Hitler when he came to power in Germany. Escape from Freedom is a psychological exploration of the social conditions that developed in Europe between the Middle Ages and the mid-twentieth century, leading to the rise to power in Germany of Hitler and the Nazis. Milgram’s experiments took place in the United States in the wake of the appalling destruction and loss of life of the Second World War and the horror of the Holocaust. The political atmosphere in the United States at the time was coloured by the Cold War, the endemic fear of communism and, in the early 1950s, the “Second Red Scare,” initiated by Senator Joseph McCarthy.

Is it appropriate to draw lessons from Milgram, Arendt, and the formative events and experiences of the mid-twentieth century to apply to behaviour today at the more mundane level of the workplace? And is this relevant only in North America and the West?

Much has, of course, changed in the five decades since Milgram published his findings. But the world increasingly feels under threat again – not from communism but from radical fundamentalist groups like Al Qaida and ISIS, not to mention climate change, globalisation, and the rapid technological advances so powerfully shaping the future of work across the globe.

The mundane level of the workplace is, in most people’s experience, anything but mundane. It influences how and where they live, their values and attitudes, their standard of living, and their hopes for the future. In times of economic uncertainty, conformity to the prevalent culture of the employer or sponsor may seem the wisest course of action. Questioning, challenging, or whistleblowing may turn out to be personally counter-productive in the longer term.

To take an example from my own British experience: the rigorous approach of some inspectors from the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (OFSTED) and the National Health Service’s Care Quality Commission (CQC) – looking for faults and shortcomings and penalising people, schools, and hospitals for their inadequacies – may actually result in depressed and debilitated teaching or medical staff who then choose to leave their professions altogether. This illustrates well the ways in which negative culture and practice can cause unexpected devastation. An opinion poll, commissioned by the National Union of Teachers (Boffey, 2015), suggests that over 50% of teachers are thinking of leaving the profession in the next couple of years, due to “volume of workload” (61%) and “seeking a better work/life balance” (57%). And people who don’t leave under such pressures can end up “burnt out” instead.

So the phrase “the banality of evil” – whether it describes just obeying orders, or following an overly rigid approach to appraisal, or excluding “the other,” or causing teacher burnout – complements all too well our experience of the “brutality of reality.”

In a short book, Humanising Work: Co-operatives, Credit Unions and the Challenge of Mass Unemployment (Beales, 2014), I have tried to explore some of the alternatives to “the way things are” in the workplace. Throughout my adult life, I have been fascinated by the place of work in our culture – and the devastating effects of unemployment on people, not only materially but also in terms of self-esteem, confidence, belonging, and even meaning. Paid employment in our society is undergoing great change, not least because of the high level of youth un- and under-employment. So the question arises: does it matter whether you enjoy your job, whether you are well motivated or feel fulfilled? Or is work just a necessary evil, a means to an end? For most people, their work determines how and where they live and what they are able to do; it affects their aspirations, their dreams, their hopes for their families and children. So – is it possible to humanise work? Or is that just an idealistic pipedream, a ridiculous aspiration for most people?

Work should be a way we can contribute to society – the exact opposite of what I described above. But that depends on designing the work experience to be beneficial rather than oppressive or even just utilitarian. This, then, is the counter argument. What can we do about it? The answer is to tackle the nature of the work experience. I want to give a number of examples here.

Taking the workplace, we should ask whether the simple, positive aspects of shared task and shared identity are challenging enough for the good of humankind. Nicola McCaffrey (2015) has illustrated clearly the power of having a positive attitude and an active relationship-building programme in the workplace:

Positive psychology can be used in many different ways to increase happiness and satisfaction within the workforce. Given that we spend on average half of our waking hours at work, many organizations and business leaders are increasingly starting to acknowledge that utilizing psychological techniques and know-how in the workplace is imperative…. In a recent survey by Virgin almost 40 percent of the respondents named their colleagues as the top reason they enjoy their work…. Furthermore, over two thirds of respondents reported that not only did those positive relationships increase their productivity, but it helped mitigate stressful and difficult challenges at work…. Whilst these strategies and ideas may sound like common sense in many ways they are too rarely acknowledged or practiced in today’s workplaces. By offering positivity, engagement, connection, meaning, and acknowledgement you can create an inspired and motivated workforce that are not only happy to be at work but are excited to contribute to the company at large.

(McCaffrey, 2015, paras. 1, 8, 49)

I fully endorse this approach – more consistent and energetic ways of community-building at work can have truly life-enhancing effects. But, somehow, the idea of the brutality of reality is never far below the surface. In too many jobs, people just see work as a means to an end – earning enough money to survive or enjoy the weekend.

An interesting piece of research into the attitudes of young British people to work was carried out in Yorkshire in 2012 by Liz Atkins. She described the ways in which:

[D]reams of fantasy futures or even fantasy occupations may be necessary to enable young people to accept the reality of “here and now.” None of these students in employment at the time of interview enjoyed their jobs or intended to remain in them in the longer term. Rather, employment was an instrumental means of meeting financial obligations, such as contributing to the family income. Most importantly, however, it provided a means of financing the social and leisure activities which formed a key aspect of their identities.

(Atkins, 2013, p. 151)

I would add, against the fantasies of those young people, that it is the responsibility of employers and managers to bring out the best – not just for the company but for the workforce. Lomas, Hefferon, and Ivtzan (2014) observed how companies seek to cultivate a positive work climate:

Levering’s (1988) Great Place to Work initiative assesses workplaces on five key qualities…: camaraderie, respect, credibility, fairness, and pride. Since 1997, Levering’s institute has produced a list of the 100 best companies to work for, surveying over 10 million employees across 45 countries, published annually by the business magazine Fortune (Moskowitz et al., 2013). The top company in 2013 was Google, whose stated philosophy is “to create the happiest, most productive workplace in the world” (Stewart, 2013). Bulygo (2013) suggests that Google’s “unique culture” is the result of detailed data analysis by its “People Analytics” (HR) team, with continual “testing to find ways to optimize their people, both in terms of happiness and performance.” An illustration of Google’s attention to detail is in its approach to food! Not only are employees treated to free, healthy meals, the eating environment is deliberately structured to foster positive interactions. For example, queuing time is maintained at an optimal 3–4 minutes: minimal enough to ensure that employees do not get frustrated at wasting time, yet sufficient to create opportunities for social interaction. This is a great instance of PP in action!

(Lomas et al., 2014, p. 92)

Humanising Work describes a Brazilian company, Semco, where there are no job titles, no written policies, no HR department, staff set their own salaries and working hours, and everybody shares in the profits. Managers are elected by their colleagues and their performance is evaluated publicly. Semco’s turnover in 2013 was the equivalent of US$240 million and it has 3,000 employees (Beales, 2014, pp. 7–8).

A Dutch company called Buurtzorg, which means “neighbourhood care,” provides nursing for elderly and sick people in their homes. In the 1990s, community nurses were grouped into organisations in order to benefit from economies of scale and ensure sickness or holiday cover. By developing nursing specialisms, the nurses’ daily schedule should improve and the new system should help plan the travel routes between patients. Central management, a central call centre, and improved planning and budgeting were introduced, leaving nurses to do the caring. By 2006, one nurse had had enough. So he set up Buurtzorg. Its nurses work in small self-organising teams serving about 50 patients in a small, well defined area. They do not have managers and call centres and, most significantly, each patient sees the same one or two nurses, so that relationships are built up. A 2009 study by accountants Ernst & Young found that Buurtzorg requires, on average, 40% fewer hours of care per client than other nursing organisations. Thus, Buurtzorg nurses spend time with their patients, get to know their families and neighbours – and patients stay in care only half as long. Buurtzorg now employs two thirds of all neighbourhood nurses in the Netherlands – over 7,000 nurses (Laloux, 2014).

In 1943, a young Catholic priest, Father José María Arizmendiarrieta, set up a technical school in Mondragon in the Basque region of northern Spain. For Fr Arizmendi, as he was known, the key concept was humanity at work – which is now the Mondragon brand. In 1956, he helped five young apprentice engineers form a co-operative business making paraffin heaters. It quickly grew. The model was simple: those who work in the enterprise should own it. Capital should be subservient to labour. By 2012 there were over 80,000 members of Mondragon co-operatives working in 289 companies and organisations in four main areas of activity (finance, industry, retail, and knowledge), across Spain and internationally (Beales, 2014, pp. 19–24).

Mondragon was born in a particular context. The end of the Spanish Civil War and the triumph of Franco meant that life for most Basques – especially those who had opposed him – would be tough. Fr Arizmendi had himself been imprisoned during the Civil War and was almost executed. The resilience of the people, their conviction that only they could help themselves, their commitment to rebuilding their communities – and their particular Basque culture, language, and identity – were all essential contributing factors.

Fr Arizmendi’s co-op ideas grew out of Catholic Social Teaching, a long but little known Christian tradition of action and reflection on economic matters, rooted in the values of love and justice but thoroughly pragmatic and committed to action. In 1891, Pope Leo XIII wrote an Encyclical, Rerum Novarum (Of New Things). Every Pope since then has added to the material, exploring how work can be fulfilling, how wealth can be fairly created and distributed, how economic justice can be practised, how owners, managers, unions, and workers can relate to each other. It is in many ways an open, generous tradition, built on the understanding that human beings are infinitely creative and well able to rise to the challenge of tackling poverty and producing enough wealth for all. It has a great vision for the workplace – where people can discover their true vocation, sharing with others in providing what the world really needs. It is a good example of applying Christian faith and values in the world of work.

My fourth example is not about the world of work, but rather about responding to the very worst in life, and the need to take responsibility for our actions. A contemporary of Eichmann’s, the German Lutheran theologian and pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906–1945) has been a powerful inspiration in my own thinking and has helped shape my understanding of work and economic, social, and political life. He demonstrated extraordinary courage in returning to his homeland from the United States at the outbreak of war in 1939 to resist the Nazi regime. Bonhoeffer, already renowned as a theological thinker pushing the boundaries of traditionalism, became involved in the bomb plot to assassinate Hitler – the command “Thou shalt not kill,” he concluded, must be suspended in order to rid the world of one of history’s greatest and most hideous tyrants.

Did Bonhoeffer expect Hitler’s assassination to end the war? Did he truly understand the consequences of his actions? There was nothing banal about him or his thinking. He spent the next year and a half imprisoned, finally in the concentration camps at Buchenwald and then Flossenbürg, and was executed in April 1945. He left behind not only his pre-war writings – perhaps the best known being The Cost of Discipleship (1937) and an incomplete magnum opus, Ethics, first published by his friend Eberhard Bethge in 1949 – but also a wide range of papers, sermons, and notes from 1943–1945, also published posthumously as Letters and Papers from Prison (first English translation 1953).

Through his anti-State activities, Bonhoeffer accepted that he was taking guilt upon himself as he wrote:

[W]hen a man takes guilt upon himself in responsibility, he imputes his guilt to himself and no one else. He answers for it. Before other men he is justified by dire necessity; before himself he is acquitted by his conscience, but before God he hopes only for grace.

(Bonhoeffer, 1995, p. 244)

Bonhoeffer’s God engages in the world and its history, not only in the personal lives of individuals. He argued that Christians should involve themselves actively in seeking to influence and shape the world. But he was a realist – he knew that engagement could not always be appreciated, so Christians and the Church “had to share in the sufferings of God at the hands of a godless world” (Craig, 1998, p. 835).

In his letters from prison, Bonhoeffer explored ideas about the role of Christianity and the Church in a “world come of age,” ideas taken up by the British Anglican Bishop of Woolwich, John Robinson, in his best-selling paperback Honest to God (1963). Two decades later, the Bishop of Durham, David Jenkins, tussled with these questions as he challenged the Thatcher Government and the National Union of Mineworkers during the devastating miners’ strike of 1984–1985. In what sense could God be described as being active in the world? What positive outcomes might be achieved from such a cruel and destructive confrontation? Faced with the brutality of reality, what might the right course of action be?

Here we see the answer to all those counter arguments that life is bad, people act unthinkingly, and nothing can change. Bonhoeffer shows it does not have to be this way. He has inspired many people, including myself.

A fifth example comes from my own experience. It was the ideas of people like Bonhoeffer and Jenkins which profoundly affected my own, especially through the first half of the 1980s when I was working in Hartlepool in Teesside, North East England. A coastal town of 95,000 people, Hartlepool had a rich industrial heritage and its steel, shipbuilding, and heavy engineering had been the key to its prosperity, especially during the two world wars. By the time I arrived, however, the town’s two main industrial employers, British Shipbuilders and British Steel, were virtually closed and the severe recession of the early 1980s saw Hartlepool top the unemployment table in mainland Britain. As an industrial chaplain, I was torn. Working among people facing such economic decline – loss of job, loss of income, loss of purpose, loss of identity – was a huge challenge and I sought to develop practical responses which could make a real difference to people, whilst at the same time wrestling intellectually and spiritually with those deeper questions of meaning and purpose.

At a time when good news was in short supply, I tapped into a network of people with a positive determination not to be overwhelmed by circumstances. We raised some money and set up the Hartlepool Co-operative Enterprise Centre in 1982, providing over 50 young people with training, skills, and a place in one of six embryonic co-operative businesses. I also became a founder board member of the Cleveland Co-operative Agency, whose aim was to nurture co-operative businesses across Teesside. The following year, I and others set up Respond!, a county-wide project developing practical responses to de-industrialisation and endemic unemployment, working with unemployed people, companies, trade unions, councils, churches, and others.

The Hartlepool Co-operative Enterprise Centre went bust after a year. But I have continued over the next three decades trying and trying again to create viable experiments which might point to new ways of being and doing – in Christian theological jargon, projects, and programmes which might serve as “models of God’s Kingdom.” For Jesus, the “Kingdom of God” was not just a future pipedream but a present reality – though, like a seed sown in the ground, one still to be fully realised.

Linking Up Interfaith was another example of practical engagement – working on urban regeneration with faith communities of all faiths across the country. I set it up in 1989 and raised the funding required, which led to my being seconded to the UK Government for three years (1992–1994) to create a new consultative body, The Inner Cities Religious Council, chaired by a Government Minister in what is now the Department for Communities and Local Government. This led to strong and positive relationships with the leaders and members of Britain’s faith communities, Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Sikh and others, and much joint work together around the country.

I left there to set up the Churches’ Regional Commission in the North East in 1994, working across North East England on economic, social, and cultural issues before returning to London in 1998 to take a regional initiative, the North East Employment Forum, onto the national stage. Employment Forum (UK) – later called Employment Focus – worked on two major themes: a Black Economic Empowerment Programme and an Inter-Faith Action Programme. In both, the approach was rooted in “praxis” – informed and values-driven action. Out of the latter programme came contact with a bewildered and shell-shocked group of Afghan refugees in East London, and this led to one of the most challenging initiatives I have ever been involved in, Afghan Action – a training and business incubation centre in Kabul, Afghanistan.

Afghan Action was set up as a social enterprise in September 2005, its aim being to focus on providing skills training to create sustainable jobs and businesses. It has provided education in basic literacy and numeracy (as most people come to us with little or no education) and vocational skills training – weaving handmade carpets and making clothes and uniforms. It has supported over 1,300 young men and women to date. By summer 2008 we had 180 staff and were supplying carpets to major British stores such as Habitat and John Lewis. However, the economic downturn nearly finished us off and, although since then we have had up to 60 people on site, it has been a continuous struggle to survive. In 2016 we were forced temporarily to suspend operations due to suicide bomb attacks in the area and increasing insecurity. I asked Afghan Action’s General Manager, Samim Faizy, to consider some questions I had devised and invite colleagues across his network to respond. I also asked for the help of Hashim Alavi and Mahboobullah Iltaf, both working in Afghanistan but former colleagues who worked with me in 2010–2011 while they were in the UK for postgraduate studies at the University of York.

I turn finally to a survey, carried out in late October/early November 2015, of the attitudes to their work of 78 public and private sector managers and professionals based in Kabul, Afghanistan. The questions were as follows:

The survey also provided an opportunity to respond, if they wished, to an open question: What are your personal hopes and fears for the future?

Some of the responses are quoted below. They make both harrowing and challenging reading from intelligent and hard working men and women in a country steeped in over 40 years of conflict, civil war, foreign occupation, and, now, the concerted efforts of the Taliban and ISIS to undermine the Government and seize power.

As can be seen in Tables 30.1 and 30.2, the comments of respondents to questions 1 and 2 varied widely regarding how much they liked or disliked their work and how safe or secure they felt. Most said they liked (32; 40%) or loved (26; 32%) their work, but the security situation was a significant factor and weighed heavily: 42 people – just over half – said that they were “nervous” or worse, although 36, or 46%, said that they were “not really worried” or have “no concerns” about safety and insecurity.

The issue of security came up repeatedly in the open-ended answers. “Kabul has been in this situation for more than 10 years,” said one person. “Half of the citizens have moved out of the country and, being from the half who stayed in town, I should get used to the idea of being in danger all the time, and try my best to keep things safe around me.” Another wrote: “Neither the work nor the situation in this country are stable.” A woman working in the public sector wrote: “It is difficult for a female to commute to work here … I do not know about my future.” A bleak comment came from a call centre employee: “Very few people have hope for the future. In Afghanistan you just go to work and come home … being afraid for your life.” A small business owner wrote: “I’m afraid of the future because the situation is bad.”

Others saw things differently. “Everything is all right, just the media shows it as negative. I am hopeful and happy with my job.” And, from an economic regeneration manager, “I am relatively satisfied.” A public sector consultant wrote: “I am trying my best in my capacity to change things.” He later elaborated with a sobering comment: “[T]he moment [the] regime collapses, people in my group will be the first to get killed by the opposition but I hope the future of the country will be better and we are not going to descend into chaos.”

Hate |

Dislike |

Don’t dislike or like |

Like |

Love |

|---|---|---|---|---|

2 |

6 |

14 |

32 |

26 |

Very insecure |

Quite insecure |

Nervous |

Not really worried |

No concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

7 |

15 |

20 |

22 |

14 |

A female respondent wrote: “I am hoping for a more secure and comfortable working environment especially for female employees. I am facing many more challenges than males in the office. Getting engaged with working society and getting used to it and learning the task I have to do is much more demanding than for a male.”

These comments illustrate a remarkable degree of personal resilience – in the face of such odds, you have to keep going, you have to hope that things will change for the better.

As seen in Table 30.3, the responses to question 3 indicate the importance of receiving an income (A) – over 80% scored this with a 1–3. But, perhaps surprisingly, the item with the next highest score in the 1–3 range, at just under 70%, was F Because my work helps give my life meaning and purpose. This was significantly more than E Because I am improving my education and enhancing my skills, which scored just over 50% of 1–3 responses. B, C and D (security, friendship, and feeling valued) barely featured in positions 1–3.

This was a small survey, and respondents did not all answer the questions in consistent ways. Nevertheless, there was a positive indication that meaning and purpose scored highly in the priorities of managers and professionals working in the public and private sectors. This challenges the idea that positive psychology is the preserve of rich Western elites.

One respondent wrote:

I am overwhelmingly becoming hopeless because of what I witness every day. In the past, the situation continued to inspire hope, but now, it has totally negatively changed. I fear the more organised and vast emergence of violence fuelled by terrorist and extremist groups.

Another was more positive: “I hope that my country will be cleansed of terrorists, bomb blasts and thieves and our people will have more opportunities for education and work.”

A third respondent wrote:

[T]he main fear is the current security situation in the country and the amount of discomfort which people have during their work regarding this issue. I hope that these concerns and fears fade away and those who work, those who study and those who get out of their home for a purpose feel safe in their city and have the hope of returning back to their home – something which at present we don’t have unfortunately.

Another said: “I don’t see any bright future for myself and my family. I think that my life is wasted.”

Two more comments: “I have hope that our country will have peace and we can go to university safely and go to work and we should help one another and try to be with each other in hard times.” And,

My hopes are that the support of the foreign countries and the efforts of the government will not go in vain … I hope they will therefore make every effort to save the gains made in the past 14 years. And that we will have the chance to have positive peace and things will generally get better.

The desire for meaning and purpose – equalling the need for income and education – also rated highest for someone whose view of the future was deeply gloomy: “In the past, the situation continued to inspire hope, but now, it has totally negatively changed. I fear the vast emergence of violence fuelled by the more organised terrorist and extremist groups.”

One respondent commented on the culture of nepotism prevalent in too many workplaces: “I fear employers will lose the trust of their employees because of inequality in the office environment.”

There are, of course, many other honest and powerful statements among the responses received. So many of these responses bear remarkable testimony to the power of a positive and creative outlook and attitude in the face of great adversity. They should be considered in relation to Abraham Maslow’s (1943) Hierarchy of Needs:

This list was later expanded to include cognitive and aesthetic needs (Maslow, 1954) and transcendence needs (Maslow, 1964). Maslow was perhaps one of the original inspirational psychologists whose work has helped give shape and meaning to positive psychology. His original five-stage hierarchy might suggest that the primary motivation for people working in danger zones would be focused more on basic (or deficiency) needs (e.g., physiological, safety, love, and esteem) than growth needs (self-actualisation).

For the Afghan respondents, Maslow’s Levels 1 and 2 are, not surprisingly, significant, especially if income is directly linked to them. Maslow’s Level 3 equates approximately to C Because I see my friends and enjoy the company of my workmates. McCaffrey (2015), quoted above, considered this to be an essential part of positive experiences of work, but it received the lowest number of positive scores in my survey. Maslow’s Level 4, and his added cognitive and aesthetic needs, link to the survey’s E Because I am improving my education and enhancing my skills – and scored well. But D Because I feel valued and respected scored lower than I might have expected. Maslow’s Level 5, self-actualisation, relates to F Because my work helps give my life meaning and purpose, and, as described above, scored surprisingly highly.

These responses suggest that Afghan managers and professionals, working in the public and private sectors around the capital, Kabul, have an intensely pragmatic outlook. They need work in order to survive and support their families. They are constantly concerned about security and safety. They value the opportunity to learn and progress. And they want their work, their commitment, their energy, their willingness to risk the constant dangers and threats surrounding them to mean something. To be purposeful. To have significance. To make a real and tangible difference to their situation and the state of the country.

In conclusion, there are many reasons why people behave badly, why the banality of evil seems to be more widespread than we may wish or imagine and why the brutality of reality is the reality most of us must learn to live with. I have described these.

But there are also many counter arguments, reasons for not just carrying on but actually struggling, against the odds, to make a positive difference. For me, the ideas of people like Bonhoeffer and Jenkins are compelling. But so, too, are the people I surveyed from Kabul, who testify to the ability to be positive even when the reality of brutality is all too present.

The discipline of positive psychology will grow in significance in the coming years. It seeks to explore human resilience, sometimes in the face of huge odds, and to identify the motivations which underlie the desire to sustain hope in the face of the brutality of reality – behind which, of course, is that deeper and more intangible idea of meaning and purpose. Its ideas and hypotheses need testing across the world, in places of war, conflict, oppression, natural disaster, poverty, ill health and unemployment. As a therapeutic tool and an aide to personal and community development, it may yet prove to play a significant and history-shaping role. But it must not avoid the brutality of reality – and, for my Afghan friends, the reality of brutality.

Large numbers of people continue to think and act positively and commit their lives to building a better world in the face of huge odds. Positive psychology must work at what it is that compels people to struggle, not just for survival and security, but for meaning and purpose and community transformation. To understand such resilience, and to be able somehow to articulate and apply what is learned, could be its greatest contribution both to the field of psychology and to human flourishing.

Atkins, L. (2013). Researching “with”, not “on”: Engaging marginalised learners in the research process. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 18, 143–158. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2013.755853

Beales, C. (2014). Humanising work: Co-operatives, credit unions and the challenge of mass unemployment. Milton Keynes, England: Rainmaker Books.

Boffey, C. (2015, October 4). Half of all teachers in England threaten to quit as morale crashes. The Guardian. Retrieved from www.theguardian.com/education/2015/oct/04/half-of-teachers-consider-leaving-profession-shock-poll

Bonhoeffer, D. (1995). Ethics. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Butler, J. (2011, August 29). Hannah Arendt’s challenge to Adolf Eichmann. The Guardian. Retrieved from www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/aug/29/hannah-arendt-adolf-eichmann-banality-of-evil

Chang, J. (1991). Wild swans. London, England: HarperCollins.

Chang, J., & Halliday, J. (2005). Mao: The unknown story. London, England: Jonathan Cape.

Coyne, J. C. (2013, August 21). Positive psychology is mainly for rich white people [Weblog post]. Retrieved from http://blogs.plos.org/mindthebrain/2013/08/21/positive-psychology-is-mainly-for-rich-white-people/

Craig, E. (Ed.). (1998). Routledge encyclopedia of philosophy. London, England: Routledge.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Herder and Herder.

Fromm, E. (1941). Escape from freedom. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Haslam, A. (2011). Milgram’s obedience experiment 50 years on: The banality of evil, or working towards the Führer? [Weblog post]. Retrieved from https://blogs.exeter.ac.uk/exeterblog/blog/2011/08/05/milgrams-obedience-experiment/

Hosseini, K. (2003). The kite runner. New York, NY: Riverhead Books.

Hosseini, K. (2007). A thousand splendid suns. London, England: Bloomsbury.

Hosseini, K. (2013). And the mountains echoed. London, England: Bloomsbury.

Laloux, F. (2014). Reinventing organizations. Brussels, Belgium: Nelson Parker.

Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., & Ivtzan, I. (2014). Applied positive psychology: Integrated positive practice. London, England: SAGE.

Mao, Z. (1967). The thoughts of Chairman Mao Tse-Tung. London, England: Anthony Gibbs Library.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370–396. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Maslow, A. H. (1964). Religions, values, and peak experiences. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

McCaffrey, N. (2015). Positive psychology and the workplace: A labor of love. Retrieved from https://positivepsychologyprogram.com/positive-psychology-workplace-labor-of-love/

Miller, A. (2008). A critique of positive psychology – or the new science of happiness. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 42, 591–608. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9752.2008.00646.x

Robinson, J. (1963). Honest to God. Norwich, England: SCM Press.

Snow, E. (1937). Red star over China. London, England: Victor Gollancz.