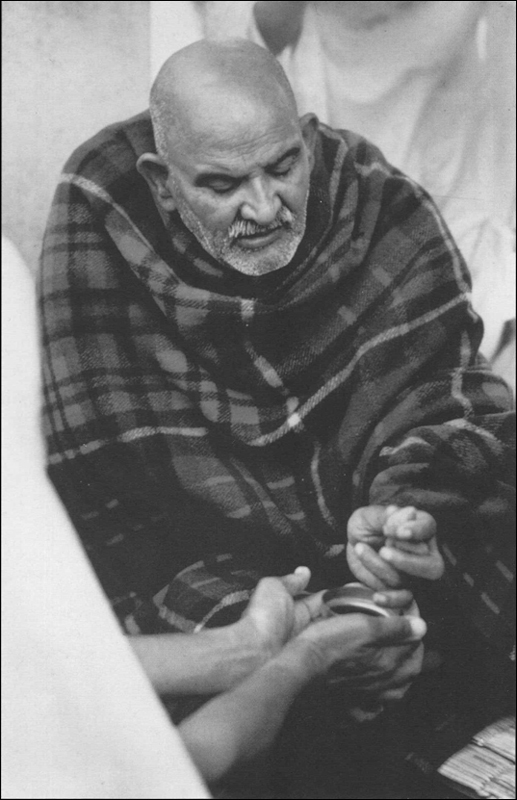

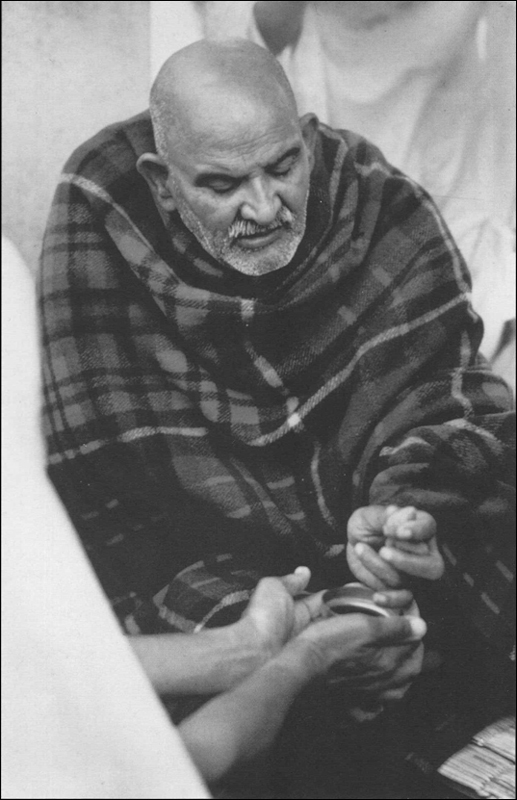

Photo: Balaram Das

Take Chai

“Take chai (tea).”

“But Maharajji, I’ve already had chai.”

“Take chai.”

“Okay.”

“Go take kanna (food).”

“Maharajji, I just ate an hour ago.”

“Maharajji wants you to take kanna now.”

“Okay.”

“Maharajji sent these sweets over for you.”

“But I couldn’t eat another thing.”

“It’s Maharajji’s wish that you have these sweets.”

“Okay.”

“Maharajji sent me to give you chai.”

“Oh no! Not again!”

“I’m only doing my duty. It is Maharajji’s wish.”

“Okay.”

“A devotee just arrived from Delhi with a large bucket of sweets. Maharajji is distributing it. He wants you to come.”

“Oh my God, I’ll explode.”

“It’s prasad.”

“Thank you, Maharajji. (Oh, no, not the apples too!) Ah, thank you, Maharajji.”

While many experienced Maharajji’s qualities of timelessness or love at darshans, everybody who came before him felt his concern that they be fed. Often even before you could sit down he would insist that you “take prasad.” People just never went away from him hungry.

I stopped at a gasoline station in Berkeley, California, run by a Sikh fellow. I thought I’d practice my Hindi with him. When he found out that I stayed at the temple at Kainchi, the first thing he said was, “Oh, you belong to that baba. I visited him. He gave me puris (fried bread). Nobody else gives you food just for nothing.”

MANY OF THE poor people in the areas around the temple or on pilgrimages came to depend upon the food that was freely given for their survival; but for the rest of us, such excessive feeding and continuous preoccupation with food seemed to indicate that the food represented something more.

My first impressions focused on all the food that was present. I had just come down from Nepal, where I had been on a strict Buddhist meditation trip for a long time, and I saw all these people sitting down and stuffing their faces! I thought, “Oh, they don’t know where it’s at. Look at the gluttons!” Then I sat down to eat … and in a few days I was stuffing my face. I had never before experienced such a feeling as that. Literally I could not get enough to eat. It was as if I were feeding my spirit.

He offered the pera (a sweet) back to me to eat, and oddly enough I turned it down. What was in my mind was that I felt completely filled and someone else should have it. So he gave it to someone else.

At another darshan he had filled my hands with peras, which I promptly ate. Shortly thereafter he started to give me another huge handful, which I turned down, thinking that I’d had my share. An Indian behind me became upset and told me I should never turn down Maharajji’s prasad, that I should always take what he offers to me. Then, of course, I felt bad. Next Maharajji offered me another handful, which I joyfully received.

I arrived at the temple in November and lived there continuously until the end of March. During all that time I was fed well, daily, and yet not a penny was ever asked of me in compensation. I couldn’t understand it. Here I was a relatively wealthy Westerner, and the Indians had such a hard time economically, and yet they would not accept payment. So I just kept sneaking money into the box at the temple. (R.D.)

I was trying to hide somewhere around the temple, across the courtyard from where he came out the door. And when he came out, I got pushed by the people right up to the tucket. I tried always to be far away and hide myself, so when I got pushed near to him I tried to hide behind the column, but people pushed me and pushed me. And Maharajji came out. I was scared and crying. And Maharajji gave me a pear. When I ate the pear it made me feel like there was water all over inside me. It was like eating love alive. Since that day this pear has always been in my mind, and nothing has ever matched this feeling. I have never eaten another pear since that day.

One time, when my daughter was young and still with us, we stopped in Bhowali en route to Kainchi for darshan. She wanted jelebees (a sweet), but there were none. I said, “When we get to Kainchi, there will be some.” But when we got there, we found that it was a Hindu fast day—Ekadashi (literally “eleventh day” in lunar month)—and so only boiled potatoes were served. As we entered Maharajji’s room, to our surprise a man arrived with a large basket full of jelebees. Maharajji said, “Give some to that girl first,” pointing to my daughter. He knows everything!

A sadhu once came to the temple and upbraided Maharajji: “You do nothing for people. You don’t feed or help people.”

Maharajji said, “Give him a room and food and money,” yet what all the devotees felt like doing was beating the sadhu. They got him around a corner to do so, but Maharajji yelled at them. After the sadhu had eaten, he became very quiet. Maharajji said, “The thing you people don’t understand is that he’s hungry. He hasn’t eaten for three days. What else could he do but what he did?”

Once I said, “Why do you feed so many people and why so much? I could eat four chapattis (flat unleavened bread) and stay alive.”

Maharajji answered, “We have an inner thirst for food. We don’t know of it. Even if you don’t feel you can eat, your soul has a thirst for food. Take prasad!”

THE NATURE OF the food that was served around Maharajji is worthy of note, for though it satisfied our souls, our intellects were often appalled. The usual diet at the temple consisted of white rice, puris and potatoes (both fried), and sweets of almost pure white sugar. The diet was starch, grease, and sugar, and much black tea. All the sensitivity that the Western preoccupation with diet had awakened in us screamed at this diet. And yet, this was “prasad.” Did you reject prasad, or did you give up your dietary models? What did you do when the love came in the form of starch, grease, sugar, and tea? Greasy potatoes were one thing; a blessing from the guru, however, was an entirely different matter.

I previously believed that a saint should observe certain restrictions as to food. Also, I never took tea or coffee, and I ate a very simple, small diet. I never took medicines. I wondered how people could take so many pills. After Maharajji left I caught a cold. At first the doctors thought it was a flu, then they said it was a more serious disease. So I had to take fifteen pills a day to cure it. It was all Maharajji’s play. The doctors also told me to put on weight so from 6:00 A.M. to 10:00 P.M. I ate. I wondered how I could eat so much when previously I had only eaten two chapattis at a meal. All my old ideas vanished.

This was similar to what happened when I came to Kainchi, prior to which time I never drank tea. On the first day at Kainchi I did not take it, and on the second day when Maharajji asked me if I would drink tea, I didn’t reply. The third morning he asked me, “Do you want tea? You don’t want it. Here, you should drink tea. It’s a cold place!” So this time I drank tea, and since that day I take anything—tea, coffee whatever.

WHEN MAHARAJJI spoke about diet he generally ignored the nutrition issues that so concerned some of us, but he did suggest that we “eat simple foods.” And he also advised us to eat food that was indigenous to the area in which we were living. And then to various devotees he gave specific instructions about diet, advising one to forego wine, meat, eggs, hot spices, “because they lead to an impure heart.” Yet to another he said, “What is this concern with what is meat and what is not. When you can live without meat, well and good. When you cannot live without it, then you should have it.” Some he counseled to “eat alone, silently, simply, or with a few people”; to others his instructions concerned the value of fasts three times a month, although when you were around him he interrupted any fast you might attempt. From this confusion of instructions, most of us came away with the feeling that he was counseling us to trust our intuitions rather than get too caught in rules. At least, that’s what we wanted to hear.

Because he fed us all so unstintingly with love and attention, as well as food, we sought ways to reciprocate. Yet his life was so simple that there was nothing to give, so most people brought flowers or food, especially fruits and sweets. These he would then distribute by his own hand or touch the food and then have it distributed. Such touching, or blessing, by such a being as Maharajji, converted the food vibrationally from a physical material into prasad. In the absence of the physical form of such a being as Maharajji, food is offered in the heart and the mind of the devotee before partaking. If food is offered purely, the beings to which it is offered accept an essence from the food. Then we eat what is left, which has become prasad. In the West, this would be similar to our saying grace before eating.

Maharajji also showed a continuous concern for the quality of the food that was being distributed from the kitchens at the temple. He would call the cooks and examine the food. If it was poorly made, he would yell; if it was unnecessarily extravagant, he would yell.

When I was living up on the hill in that little kuti (hut), Maharajji would send me away with a box of food every evening. But when he gave it to me he always checked the entire box, putting his hands all through it.

Maharajji would tell the Mothers that the vibrations with which food was cooked could definitely affect your state of mind. He would say that if you truly made your food prasad, it would purify you. But even a very pure man, if he ate food that was prepared without proper consciousness, that food would create confusion in his mind. He said that eating purely prepared food made a yogi great.

At the market I bought some clusters of green berries to give to Maharajji. They were kind of dirty so I very carefully washed them. Then I put them back into the bag. But you know how it is with Indian bags. It broke and the berries fell all over the ground, so I carefully washed them again, berry by berry. It took a long time. Finally I brought them to Maharajji; everybody else, of course, had also brought fruits. But the minute I put them down Maharajji appeared very excited. He spread them all out very carefully, studied them, ate many of them himself, and distributed the rest as something particularly precious. I felt that he sensed the love and care with which I had prepared the berries.

For some time, Maharajji would eat only the food prepared by one particular Ma. She told me that if one day she was too busy and someone had helped her with it, he would refuse to eat it. She said that she would sometimes lie to him just so he would eat the food—she would say that she had cooked the food by herself without help. Still he would push it away. He seemed to be able to feel the difference.

My Brahmin grandfather took his food alone, as was the tradition. The food was specially prepared for him by my wife. He had started to eat when Maharajji arrived, so father ordered more food prepared. My wife wanted to give Maharajji a special item of food that she had made for grandfather, so she gave some to Maharajji. Father got angry.

“How can you give Maharajji other than freshly prepared food?” he asked my wife.

Then Maharajji called him and said, “The freshly prepared food was eaten by the sadhu. The special food offered out of such pure love was eaten by God.”

MOST OF THE time Maharajji ate alone and distributed all that we devotees brought to him. But it was each person’s dearest desire, when we brought the fruit or other food, that Maharajji eat some of it himself. And when he did, it felt like such a precious moment, one in which Maharajji had accepted a token of your love.

Once when I brought a soft apple and peeled it and cut it up and held it up before him as I had seen the Indians do, he reached down and took a few pieces from my hand … and I experienced that ecstasy you might feel if a wild bird or deer had come and eaten out of your hand. (R.D.)

Living in the ashram at Kainchi I seldom had the opportunity to buy anything to offer Maharajji. Somehow I obtained a pomegranate one day. I waited until late afternoon when Maharajji would walk to the back and give darshan outdoors in front of the showers. Only a few ashram guests along with an occasional VIP or a villager coming on business would be present for darshan after the last bus had left. It was an intimate hour which glows in my memory like the setting sun on the hilltops across the valley.

I was removing seeds from the pomegranate and offering them to him. He would eat a few and hand out a few and, once they were shelled, I would give him a few more. As I was running out, an Indian matron passed her handful of jewel-like seeds under the tucket to me so that I would have more to pour into his hand. By the time these were gone she had a few more for me. This continued in a very casual manner. We all, Maharajji included, acted as if nothing unusual were going on under the tucket. She obviously enjoyed, as much as I, to see Maharajji accept and eat our offering and to play this truly delightful game with him.

I purchased a dozen oranges to take to Maharajji. We arrived at the tiny temple where Maharajji was visiting and where many Indian devotees already had gathered and were crammed into his room. As soon as our presence was made known, we were pushed to the space just in front of the wooden table on which Maharajji sat. I offered the oranges to him. There was already much fruit and some sweets on the table. But then something happened that surprised me. Maharajji started to go at my oranges as if he had never seen food before. As each orange was opened he would grab it and eat it very rapidly. And before my eyes he consumed eight oranges. I was being fed the other four, at Maharajji’s insistence, by the school principal.

Later I asked KK, a close Indian friend, about this peculiar behavior. KK explained that Maharajji was “taking on karma” from me and that this was a technique by which he often did that. (R.D.)

THE MEANING OF taking on karma is that a very high being, such as Maharajji, can work with subtle vibratory patterns and can take from devotees patterns with which they have been stuck for this lifetime or many lifetimes. For example, such a being could take away your sorrow or your ill fortune.

This process, which is a familiar one among Indian saints as well as sorcerers and medicine men from many parts of the world, can be done in a variety of ways. Often the medicine man works with a lock of hair or the feces or urine of the person suffering the effects of some negative forces, either inside or outside themselves. In India, such karmic healers often work with things the devotee gives them. Shirdi Sai Baba, a very great saint of India, would ask his devotees for annas, small coins worth less than a penny. These he would handle continuously until he had extracted the negative condition from the devotee into himself. This negative material he then could release from himself by other yogic processes. Another well-known guru in India asks his devotees for cigarettes and smokes from morning till night, year in, year out, often three or four cigarettes at a time. Maharajji’s way was to eat the karma, and he seemed to have no limit to his capacity. One woman, a long-standing devotee, told the following story:

Once in Bhumiadhar, where Maharajji was staying the night, we had all taken our evening meal and had retired at 10:30 P.M. Around 1:00 A.M. Maharajji started yelling that he was very hungry and that he must have dal (lentils) and chapattis. I awoke and reminded him that he had already eaten. But he insisted that he must have dal and chapattis. Who can understand the ways of such a being? So I woke Brahmachari Baba (the priest) and he built a fire and prepared the food. It was ready about 2:00 A.M. and we watched Maharajji consume the food with great hunger. Then we all retired again. At about 11:00, the next morning, a telegram arrived saying that one of Maharajji’s old devotees had died down on the plains (about 150 miles away) the previous night at 2:00 A.M. When the telegram was read to Maharajji he said, “You see, that’s why I needed chapattis and dal.” This aroused our curiosity, because we didn’t see at all. We pressed him but he would say nothing more. Finally after two or three days of our persistence he said, “Don’t you see? He (the man who had died) had been wishing for chapattis and dal, and I didn’t want him to carry that desire on through death for it would affect a future birth.”

SOMETIMES WHEN visiting homes he would come to the door and say he was very hungry and ask if he could eat. In very poor homes where there might not be any food, he would just say he was very thirsty and ask for water.

In Lucknow, Maharajji took some public-works officials in a car to the poorest part of town where these officials do not take proper care of the roads and sanitation. From one of the shacks he called forth a Muslim (whom Maharajji called “a Musselman”) and they embraced, and then Maharajji said,

“I’m very hungry.”

“But Maharajji, I have no food.”

“Ap! Wicked one! You have two rotis (flat bread) hidden in the roof!”

The man was surprised that Maharajji knew, and he got them. Even though Maharajji and the officials had just eaten, he ate one with relish and handed the other to the officials including the Hindu Brahmins, who would never eat food prepared by a Muslim, and said, “Take prasad!”

When Maharajji came to the Lucknow temple for the last time, he would say to each person who came (if he or she could afford to do so), “Go! Get sweets,” and when they would return with sweets, he’d distribute them, almost fifteen hundred rupees worth that day. One doctor bought a thousand rupees worth of sweets, and the personal problem causing him concern was solved.

IN THE PERIOD between 1939 and 1949, when Maharajji would come into a town such as Nainital, all the women would prepare food in the hope that he would come to their homes. They did it out of a mixture of loving service and the feeling that it was a blessing to feed such a saint. And KK, who followed him from early morning until late at night, once watched him consume twenty full meals in one day. Another reported watching him take ten meals in a row. And if you have been to India and understand the graciousness of the Indian home, where the guest is treated as God, you will appreciate the immense portions and the persistence in feeding. An Indian meal is more than ample for a normal human being.

But perhaps Maharajji s immense capacity represented something other than dietary requirements.

One morning Maharajji said to the people at the ashram, “You people can’t feed me or take care of me. I’m going to Ma. She’ll feed me.” And he left for the ashram of Ananda Mayee Ma, a great woman saint of northern India. During the entire trip he was saying, “She’ll feed me. I’m going to see Ma. She’ll feed me.” Then he burst into the darshan room like a child of five, with his blanket flying in all directions. She was sitting there and he was saying, “Ma! Feed me. Feed me, Ma!” She exploded in laughter. A huge meal was brought to him and the two of them passed it out to all the devotees.

AGAIN AND AGAIN Maharajji enjoined us to feed people. His concern was not merely for his own devotees but with all people who hunger. He would say, “God comes to the hungry in the form of food.” And to the cooks he would say, “Making food is a service to God. People need food to stay alive.”

He used to say that you should serve everything, every creature. “It is all God’s creation. Serve everyone, whether he be a dacoit (thief) or anything else. If he comes to you hungry, give him food.” So often he said, “Everyone has a right to be fed.”

MAHARAJJI’S OWN BEHAVIOR set a dramatic example for us.

Besides feeding all who came to have his darshan, he was continually arranging for large bhandaras (celebrations consisting of mass free feedings for all comers, including the wealthy, the poor, the beggars, the lepers). The people were fed when they arrived, for Maharajji instructed, “A starving person should not have to wait. Such a person should be fed when he is hungry.”

At these great bhandaras, which often served a thousand or more, many devotees would vie to help in the preparation and distribution of the food. Here judge and merchant, teacher and politician, could all be found peeling potatoes, stirring the huge pots, or ladling out the halva or rice with huge spoons. The Kumbha Melas were even more festive occasions. These are gatherings of hundreds of thousands of sadhus, saints, and seekers who come from all over India in order to bathe in the confluence of three rivers—the Ganges, the Yamuna, and the Saraswati, an underground spiritual river, at an auspicious astrological moment. It is like a huge spiritual fair that goes on for a month or more. At the melas Maharajji’s tent usually served 250 to 500 a day for at least a month. That is a lot of potatoes to be peeled!

During these celebrations Maharajji demanded hard work of the devotees, and many saw these experiences as training in discipline. One devotee describes the experience this way:

At the mela, they prepared khichri (a rice and dal mixture), but the serving spoon was very heavy and soon the servers, growing tired, began to serve only small portions. As a result, the beggars would stand in line again and again to get enough to eat. Finally one of Maharajji’s devotees got very angry and just then Maharajji arrived from Chitrakut (a place sacred to devotees of Ram). He yelled at them all and said they could not serve food with anger and that they should give plenty to everyone.

ANOTHER person pointed out that the devotees were not even praised for working hard:

No matter how hard people worked at the melas and bhandaras, Maharajji would say, “You people are playing and going about doing nothing. You are always sleeping.”

Although people were continually bringing food to Maharajji, which he distributed, sometimes there were more to receive than there were givers. It was at these times that the discerning eye caught Maharajji manifesting what is known as the “siddhi (power) of Annapurna.” Annapurna is the Goddess of Grain, the aspect of the Divine Mother that feeds the universe. One who has Annapurna’s siddhi can keep distributing from a store of food, yet it will remain full.

On a feast day at the temple when I was quite young, they were giving out special sweets. Maharajji gave me a small leaf cup of these sweets that he had been keeping especially for me. Then he said, “You give those sweets back to me.” So I gave them to him, because I had such faith in him. He just put the leaf cup under his blanket and began distributing those sweets from under his blanket. I don’t know how he did it, but he gave a handful to each person in that huge crowd of at least a thousand people. I was so surprised. I couldn’t understand how he could be distributing so many more sweets than the number of sweets I had given to him, so, being just a kid, I stuck my hand under his blanket and took out the leaf cup to see. Maharajji turned to me and said, “Now the magic is finished.”

A man brought some oranges to Maharajji and put them in an empty basket by his side. Maharajji started giving the oranges to the people in the room and then to others in the temple. The man had brought eight oranges, and Maharajji gave out forty-eight.

At the mela, many came to the tent and Maharajji told us to prepare tea for all those people. No one wanted to tell Maharajji that they had run out of milk. Finally someone did, and Maharajji said, “Go and get a container of water from the Ganga and keep it covered with cloth.” All that day and until midnight that night, there was plenty of good tea with milk.

Maharajji called me over to sit with him while he was throwing prasad. He was eating small biscuits from a small plate with only a few biscuits. Maharajji started giving me biscuits, taking them out of the biscuit plate with his hand. He kept taking more out, until both my hands were full and I couldn’t separate them because of the amount of prasad. Earlier I had been upset observing Maharajji, thinking, “Prasad should be given, not thrown.” He knew that, and this is why he called me back and started giving me prasad into my hands.

Maharajji once called me in Allahabad to tell me he had come down to Vrindaban. When I arrived at the Vrindaban ashram, there were only a few people there. One woman came for darshan, bringing a bag of wonderful apples. You can’t imagine how big and luscious-looking they were. Maharajji began distributing them and I thought surely he would give me one as well. But he didn’t. He gave a few to the other devotees and the rest he gave back to the woman. She wouldn’t give me one, either. Oh, how tightly she tied them back up in her bag!

Shortly afterward, Maharajji crossed the yard and went into a room alone and sat on the tucket in there. Then he called me in alone. I don’t know from where it came, but he put his hand down beside him on the tucket and handed me an apple—even bigger, more luscious than those the woman had given him. And then he handed me another apple. I don’t know where they had come from because I had seen for myself that he hadn’t kept any from the woman!

I was accompanying Maharajji from Allahabad to Vrindaban by train, when in the station, before we boarded the train, I saw the loveliest large juicy oranges. For a moment I was tempted to stop and buy some, but I passed by. Once we were in the train, my attention was diverted just for a short time, and when I looked again at Maharajji he had beside him such a huge basket of oranges! I don’t know where they had come from, but they were better than those I had seen in the station.

When Maharajji handed me one orange I put it in the right breast pocket. The second orange I put in the left breast pocket. They created such bulges that I looked like a woman! Then he handed me a third, which I put in one pants pocket, and a fourth, in the other pocket. And he kept on giving me more, so that I had to catch them in my shirttail—front and back. He gave me so many oranges I could hardly move! I started giving these sweet oranges out to others, saying, “This is the best prasad I have to offer today.” To this day I don’t know how he came by those oranges.

At the Kumbha Mela in 1966 Maharajji was sitting on the bank of the Ganga with two or more sadhus. He told us to bring him a lota (pot) of Ganga water. He held it for a few minutes and then told us to distribute it. It was milk.

TO ALL BUT the closest devotees, Maharajji tended to mask these powers and would often use a cover story to make it appear as if he had nothing to do with the additional food.

When Maharajji established a Hanuman temple on a site that had previously been a burial ground, a great bhandara was held to set free the “wandering spirits.” Late at night it was discovered that the ghee (clarified butter) had run out. The man in charge of stores went to Maharajji and told him that there was a shortage of ghee, although many people were still coming to be fed. How were they to provide? Maharajji replied, “Go there and check among the empty canisters! You’ll find somewhere a full tin.” Although the man knew that they were all empty, as he himself had checked and counted them, he went. And, indeed, he found a full tin there among the empties.

One man stayed with Maharajji for many years as a sort of attendant. He’d keep Maharajji’s clothes, help him bathe and fetch water, and so forth. He performed much service and slept at Maharajji’s feet to be always nearby. His practice was to keep fast on Tuesday, taking only milk. On one Tuesday, Maharajji offered him food but he refused, saying he’d take milk. The whole day passed and he wasn’t given any milk.

Late at night Maharajji asked him if he’d eaten or drunk milk. He said no, he was fasting, but milk he’d had. Maharajji said, “You’re lying! Tell the truth! No one gave you milk.” Maharajji’s shouting woke the ashram. Maharajji questioned the cook and found that no one had remembered to give him his milk, and by now none was in the ashram. Maharajji got up and went to his room. He called the man in and told him to lock the door.

Maharajji asked the time; it was after midnight. Maharajji said, “You haven’t eaten all day. It’s after midnight. Can you eat now? It’s Wednesday.” The man said he could. Maharajji reached into his dhoti (cloth used to cover lower part of a man’s body) and took out five parathas (fried bread) and two types of vegetables. Maharajji said, “It’s God’s prasad, Ram’s prasad.” The man started to leave so he could eat it outside, but Maharajji stopped him and told him to eat it there. When he was finished, Maharajji produced a small amount of khir (sweet rice pudding). This the man also ate and then started out of the room to get water. Maharajji again stopped him: “Where are you going? Here’s water.” Water was kept near Maharajji’s bed for his use in the night, but the man wouldn’t use Maharajji’s vessels. Maharajji poured the water into his mouth. Then Maharajji told him not to tell anyone about the evening.

OFTEN THIS PROCESS of disguise would involve incredible abuse and yelling at devotees (shifting attention, as any good magician would do), thus creating in them great guilt, as if it were their own sloppiness that had led to the misplacement of food. Later he would be very tender with them, and they sensed that he had used them but not abused them.

One time they ran out of ghee at Hanuman Ghar, and Maharajji asked a devotee, in secret, to get some water in a bucket and put it in the woods. Then he said, in his usual direct manner, “I have to go piss,” and he went out. When he returned, he was yelling. He went over to a sadhu and berated him for not watching the supply. He said thieves were going to steal the ghee. “Look,” Maharajji said, “they have put a tin of ghee out here in the woods.” And they brought in the bucket filled with ghee.

A devotee was serving at a bhandara at Kainchi. They were starting to run out of malpuas (sweet puris), as the feast had continued for ten days. When the people came, they began to give them chapattis and dal, but no malpuas. Then sixty or seventy women arrived from distant villages, not just to see Maharajji but because they desired malpuas. Maharajji said, “Give them malpuas.” A devotee told Maharajji that there were no more, and Maharajji upbraided him, saying, “You are a thief. There were plenty of malpuas. You’ve stolen them. Take the keys from him. I don’t want him in the temple anymore. He should not have the keys to the storeroom. He has probably hidden the malpuas somewhere.” When someone checked the storeroom, there were plenty of malpuas. Later Maharajji was so loving and tender to the accused devotee.

I was in Allahabad with Maharajji at mela time. Maharajji said there were some Ma’s who had come from Nainital and added, “Let’s go to the mela grounds and find them.” We took a taxi, which Maharajji dismissed once we arrived. It was dark and many thousands of people were crowded there. Maharajji sent me and a friend to look, but we were fearful of losing him, so we made only a cursory inspection and rushed back, saying that we could not find the Ma’s. Finally Maharajji said he would go. In the third tent that he investigated, he found them just as they were finishing a puja to Maharajji. They had been doing this puja every day for thirty days, hoping for his darshan. This was the final day. They had even made an image of Maharajji.

Maharajji walked in and stood at the back of the tent, then he brought the Ma’s to another devotee’s house and sent us out for milk and sweets. We were students and did not want to spend all our money, so we said to each other, “After all, how much can a Ma drink?” We brought small amounts of sweets and milk, for which Majarajji berated us and threw us out. We sat on the porch, repentant. Later he called us into his room and asked, “Do you think I needed you to get sweets?” And there in the room were buckets and buckets of sweets, and Maharajji made us eat and eat.

THE RETIRED superintendent of prisons of Lucknow, a very old and respected devotee, tells of his experience with Maharajji. The story is very special in that it reflects the faith of his wife, which was sufficient to allow her to let Maharajji’s siddhi of Annapurna work through her.

He would put you in the wrong, catch you unprepared, then help you. One night in Nainital we had returned to our house for the evening meal, after having been with Maharajji much during the day. There were four of us, and my wife had prepared just enough food for our family. Then my small daughter heard Maharajji passing by on his way from the government house and she went out and said, “Maharajji, we live here. Come to our house.”

I called her and said, “Don’t bother Maharajji. We have been with him much today.” Also I realized that we had only a little food.

But Maharajji said, “No, I must go to your house,” and he came in, bringing about twenty people. After a very few minutes he said to me, “These people are hungry. Give them food.” I wouldn’t say no because I knew his strength, so I went toward the kitchen. Maharajji yelled, “And hurry up!” In the kitchen I whispered to my wife the dilemma we were in. We had only enough vegetables in the small pot for the four of us, and the market was far below and already closed.

My wife, who had more faith than I, said, “Don’t worry. Maharajji will take care of it. Here, take this small pot (which she had covered) and don’t remove the cover to look inside. And there is a large serving spoon. Just serve the people and I will make the puris.” I did as she said, not looking inside. I knew it was going to be very odd.

To each person I gave one or two large spoonfuls, then asked each, “Do you want more?” Some said yes and I gave it to them. Everyone got as much vegetable and puri as they wanted.

Maharajji was smiling. Then he said, “Everyone has taken. Everyone is full. This is a very big feast.”

A NUMBER OF stories of the “early days” have filtered down about Maharajji. How much is fact and how much is fiction is uncertain. Here is a delightful example:

The village children of the area often came to the lake, herding their cows and goats. One day, seeing no one around, they hung their lunch bundles in the low-hanging branches of the trees and went off to play. They returned to find their lunches missing and Maharajji sitting contentedly under the tree. He smiled at the children, and in exchange for their food he pulled puris and laddus (a sweet particularly favored by Hanuman) from under his garment. The children ate to their hearts’ content.