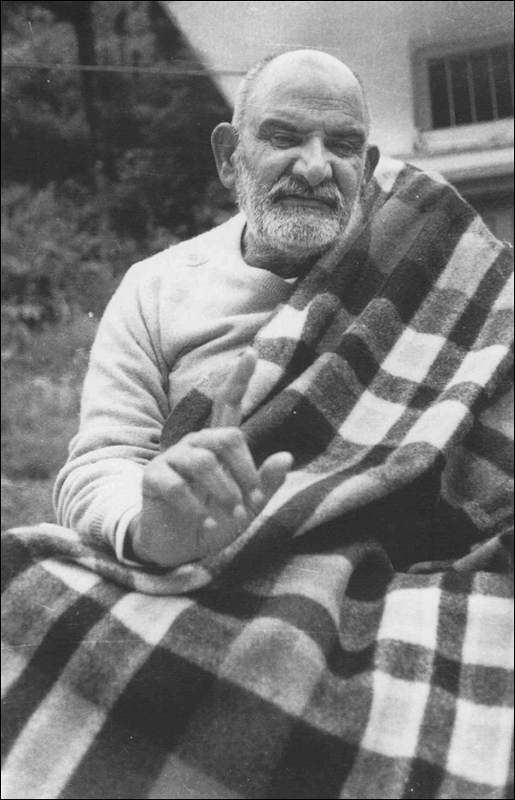

Photo: Pyari Lal Sah

About Truth

IN TRYING TO understand Maharajji’s teachings about truth, one would have to decide whether what Maharajji did or what he said was the more accurate reflection of those teachings. On the one hand, he was continually instructing devotees to tell the truth, no matter what the cost.

TOTAL TRUTH IS NECESSARY. YOU MUST LIVE BY WHAT YOU SAY.

TRUTH IS THE MOST DIFFICULT TAPASYA. MEN WILL HATE YOU FOR TELLING THE TRUTH. THEY WILL CALL YOU NAMES. THEY MAY EVEN KILL YOU, BUT YOU MUST TELL THE TRUTH. IF YOU LIVE IN TRUTH, GOD WILL ALWAYS STAND WITH YOU.

CHRIST DIED FOR TRUTH.

WHEN ASKED HOW THE HEART COULD BE PURIFIED, HE SAID, “ALWAYS SPEAK THE TRUTH.”

A man came to Maharajji, and Maharajji asked him for some money for bricks for an ashram. The man said he had no possessions and went away. Later he came rushing to Maharajji, saying his shop was burning and that he would be ruined.

“I thought you said you had no possessions!”

“Oh, I was lying ….”

“You are lying now. Your shop is not burning.”

The man went away and returned to his store—and found that only one bag of chili was smoking.

I had given the first copy of Be Here Now to Maharajji when it arrived. He had asked one of his devotees to put it inside his room, and I had heard nothing more about it. Five months later I was called from the back of the temple. When I arrived at Maharajji’s tucket he was holding the book. His first comment was, “You are printing lies.”

“I didn’t realize that, Maharajji. Everything in the book I thought was true.”

“No, there are lies,” he said accusingly.

“That’s terrible,” I said. But I was confused because I wasn’t sure whether he was serious, so I asked, “What lies, Maharajji?”

“You say here that Hari Dass built the temples.”

“Well, I thought that he did.”

At that point Maharajji beckoned to an Indian man who was sitting nearby and asked him, “What did you have to do with the temples?”

“I built them, Maharajji.” Maharajji looked at me as if this proved that I had lied.

Then Maharajji said, “And you said Hari Dass went into the jungle at eight years of age.” Again he called another man forward, who ascertained that Hari Dass had worked as a clerk in the forestry department for some years.

All I could lamely say was, “Well, someone had told me that he went into the jungle when he was eight years old.”

Again and again Maharajji confronted me with things I had said that were not true.

Finally Maharajji said, “You believe everything people tell you. You are a simple person. Most Westerners would have checked. What will you do about these untruths?”

My mind spun. What could I do about it? The first printing of thirty thousand was already in the stores and certainly couldn’t be called back, but Steve Durkee had written that they were about to print another thirty thousand. So I said, “Well, I could write and have the lies deleted for the next printing.”

“Fine. You do that. It will hurt you if you are connected with lies.” And with that he turned to other matters. I surveyed the damage in the book and prepared a letter for Steve at the Lama Foundation in New Mexico where the book was published. It would only be necessary to delete two entire paragraphs. Although the changes seemed of minor importance, I considered Be Here Now to be Maharajji’s book, and if Maharajji wanted it changed, it had to be changed.

About two weeks later I received the reply from Steve, who said that the changes couldn’t be made in the next printing. When he received my letter at Lama, which is up in the mountains north of Taos, he had just returned from visiting the printer in Albuquerque. On that visit he had arranged for the reprinting, and the printer, as a favor, was going to rush the job and put it on the press the next day. The press would print, cut, and assemble the entire book in one continuous process. Steve had then done other business for two days on the way back to Lama, and though he hadn’t spoken to the printer (because there are no phones at Lama), he was sure that the job had been done. But he assured me that the changes would be made in the following printing, which would probably occur in three or four months.

With the letter in my jhola (shoulder bag) I took an early morning bus to Kainchi. As I entered the temple, Maharajji yelled, “What does the letter say?” It always struck me as humorous when he did that, for if he knew there was a letter he obviously knew what it said. He just wanted me to tell him. So I reported, and when I had finished he said, “Do it now.” I repeated the explanation patiently about the Web press and that the changes couldn’t be made for these thirty thousand copies. And he repeated, “Do it now.” I explained that it would mean throwing out all thirty thousand books and a loss of at least ten thousand dollars. Maharajji’s retort was, “Money and truth have nothing to do with one another. Do it now. When you printed it first you thought it was true, but once you know it isn’t you can’t print lies. It will hurt you.”

Well, if Maharajji wanted it changed now, then that’s the way it would be. It would mean the loss to Lama of all the profits, and they weren’t going to be overjoyed about that; but, after all, the entire sum of money came from Maharajji anyway. Although it was not yet 9:00 A.M., Maharajji sent me from the temple, telling me again to, “Do it now.”

I thumbed a ride back to Nainital and cabled Steve with the new instructions. About a week later I received the reply from Steve. He reported that the strangest thing had happened. When he had gone to the post office, my cable was there, and in the same mail was a letter from the printer. It seems that immediately after Steve had left, he had proceeded as promised to put the plates for reprinting the book on the press. But the printer found one plate of one page—a full-page photograph of Maharajji—missing. So he went to the files, thinking he would get the original and make a new plate, and much to his surprise he found that the original of that page was also missing. Not knowing what to do, the printer pulled the job off the press and was holding it for further instructions. So, Steve concluded, it took only a phone call to change the two paragraphs, not ten thousand dollars as I had feared. I rushed back to Maharajji with the news, but that day and the next he never gave me a chance to speak. (R.D.)

When Dada’s sister-in-law was visiting, Maharajji called me up to his tucket in her presence, pointed at this woman, and asked me if I “remembered” her. In truth I did not, but it seemed like something of a faux pas not to remember, so I smiled knowingly as though I did. Maharajji smiled as though he accepted this and said, “Yes, she is Dada’s sister-in-law.”

Then that insidious “cleverness” took over and I reasoned to myself that if she was Dada’s sister-in-law I had probably met her in Allahabad where Dada lived, so I said, “Oh, yes, we were together in Allahabad.”

To which she said, “No, we never met in Allahabad. We met here in Kainchi last spring.” I was caught red-minded. Maharajji turned to me and held up that finger which, in this case, clearly meant, “Caught you! Watch it!” (R.D.)

In Allahabad, Maharajji caught me in what we in the West call “a little white lie.” We were gathered around him, and in the group was an important official of the state supreme court. For the first time in all the years I had been with Maharajji, I heard him telling the official what an important person I was in the United States, that I was a professor and wrote books. All of that seemed so irrelevant when I was around him, and it sounded strange to hear him plugging my Western social-power virtues. When he stopped, the supreme court official said to me, “I am honored to meet you. Perhaps you would like to visit the supreme court.”

The dual fact that I came from a family of lawyers and that I was in India in order to immerse myself in the spirit, made the entire prospect of such a visit unappealing to me. And yet, he was an important person and I couldn’t just say what I had been thinking. So I said, rather ambiguously, “That would be very nice.”

At that, the official said, “Would tomorrow at 10:00 A.M. be convenient?”

I was trapped, and I could think of only one way of escape. I said, “We’ll have to ask my guru. It’s up to him.”

So the official asked Maharajji, and he answered, “If Ram Dass says it would be nice, he should go.” And then he looked at me in a way that could only be interpreted as, “Got you again.”

The story of the next day’s events shows that even simple people like me do learn. I visited the court with this gentleman, and in the course of the visit we stopped in the chambers of the law review, where the lawyers all hang out. It was at the time of Nixon’s dramatic approaches to China. When all these lawyers saw an American with this important official they surrounded me and questioned me about Nixon’s China policy, which was of considerable concern to India. I gave as erudite an answer as my reading of the situation would allow. That evening when I was once again at darshan with Maharajji, another dignified-looking gentleman, who turned out to be the leading lawyer in the city, took me aside and asked if I would be willing to address the Rotary Club and the Bar Association. I got a sinking feeling that if I didn’t watch my step I would be on the creamed vegetable circuit of India. And remembering the entrapment of the day before, I said, “I’d prefer not to speak before either of these groups, but of course I will do whatever Maharajji says.”

So the lawyer pleaded his case before Maharajji, and Maharajji seemed delighted at the invitations. He kept repeating them to all who would listen as if to imply that such invitations were a major coup, a great breakthrough, and very important. I began to feel betrayed by Maharajji. Then Maharajji turned to me and asked, “What are you going to speak about?”

I thought quickly and grasped at the only association that came to mind: “I’ll talk about law and the dharma.”

“Aha!” said Maharajji, “and will you talk about Christ?”

“Of course.”

“And Hanuman?”

“Certainly.”

“And me?”

“Absolutely.”

By this time the lawyer was looking a little green about the gills, and he interjected, “Well, we thought he might talk about Nixon’s China policy, Maharajji.”

Maharajji looked shocked. “Oh, no! Ram Dass could not do that. He can only speak about God.”

The lawyer then backed off, saying, “Well, that wouldn’t be quite appropriate. Perhaps I can gather a few lawyers at my home to talk about God.” Needless to say, he never did. I had learned my lesson. Maharajji would back me up when I spoke the truth, no matter how difficult it might be.

In the intervening years I have often found myself about to lecture to one or another secular group and wondering what I should say. Then I hear the reminder, “He can only speak about God.” (R.D.)

IN CONTRADICTION TO all of these teachings, however, Maharajji frequently lied. Because of this, when Maharajji predicted something no one knew whether it would actually happen. Although his lying was pointed out by those in the local communities who did not like him (and there were a number, because he was so outspoken), such inconsistencies made no difference for the devotees. For us, perhaps the lesson was that a free being has his or her own rules; but until you are free, you’d best tell the truth.

Maharajji would usually agree to any request from a devotee. People frequently invited him to come and bless their homes and to partake of the food prepared by the family. He would inevitably agree to all these requests, yet more often than not he wouldn’t go.

When questioned by one of his devotees about his habit of making and breaking promises, Maharajji replied, “I’m just a big liar!”

A devotee asked Maharajji why he always told nice things to people, or predicted a bright future, when in fact he knew that the opposite would happen. Maharajji replied, “Do you expect me to tell people that their loved ones will die? How can I do that? All right, since you advise me, from now on I’ll answer people frankly.” A while later, a woman came for his blessing that her husband get well. Maharajji shouted at her, “Mother, why have you come here? Your husband is at home in bed dying and in a coma. He can’t be saved. You should go!” Shocked and hurt, the woman left. Maharajji was equally blunt with a few more people. Then he asked the devotee, “How can you expect me to be blunt with people? How can I hurt their feelings?”

Maharajji would lie to someone so as not to hurt their feelings; but then he would tell the truth in some other way. When K asked about his sick mother, Maharajji said, “Who will feed you if she is not here? She will be around for a long time.” But then Maharajji called a specialist from Agra and had her examined.

The specialist said, “This woman cannot survive more than twenty-eight days.”

This surprised the doctor because he had never used that number, saying, rather, a month or two. On the morning of the twenty-ninth day she died. K felt that Maharajji brought the specialist as a hint. Saints give clear hints, but we can’t always understand them.

Maharajji would say something and later, if he contradicted himself and the contradiction was pointed out, he would say. “I didn’t say that.”

I wrote for Maharajji’s blessing just before I was to take an exam. “Will I pass?” I asked him. But there was no reply. I failed. Heavy with the weight of my first failure, I ran to Kainchi and found Maharajji smiling. I told him that I had sent many letters and he hadn’t answered.

He replied, “You wanted to know. I can’t speak a lie, and the fact was very bitter.”

“Shall I appear for the exam again?” I asked.

He replied, “Yes, this time nobody will stop you.”

I passed.

Once two men came for darshan. As they stood before Maharajji, telling him all sorts of glorious things about themselves, he grew increasingly more impatient. When they reached a stopping point, Maharajji gruffly sent them away. As they were walking away, he turned to us and said, “They stand there telling me lies—they were trying to fool me! Don’t they know that it is I who am fooling the whole world?”