About Money

“KANCHAN (GOLD),” Maharajji would say and shake his finger. That and sexual desire were the two main obstacles to realizing God. Again and again Maharajji warned about these fatal attractions, these clingings; but how few of us could hear him. He referred to the Western devotees as kings. Most of us had come from comfortable economic backgrounds and so we knew that financial security would not in itself bring liberation from suffering. To know such a thing was a great step forward on the path. Many of the Indian devotees had known only financial hardship and deprivation, and for those people it was often hard to hear that worldly security was not one and the same as freedom. Yet there were some devotees who, though they had never tasted of material security, seemed to have no concern with such matters. It was as if they were truly born for God.

To each person Maharajji reacted in a different way about money. To those for whom the attachment to gold was not the primary obstacle, he never mentioned the subject. With others he talked about money all the time, awakening in the devotee both paranoia and greed, rooting out, perhaps, the sticky karma of that particular attachment. Most frequently Maharajji seemed to be suggesting that people keep as much as they needed to maintain their responsibilities to body, to family, and to community, and distribute the rest to the poor. He kept reminding us that if we did that and trusted in God, all would be taken care of. Sometimes he gave us a rupee or two, which seemed at the time like he was giving us a boon of future financial security. Some of the devotees held on to those rupees and have never since known financial need. Others gave the rupees away immediately to the first beggar they met; those devotees have not known need, either. Such a boon is known as the “blessing of Lakshmi (the goddess of wealth).” Such a blessing was clearly Maharajji’s to bestow.

In 1969 I wrote to KK, asking if I could send some money to Maharajji. The answer from Maharajji, delivered to me in a letter from KK, read: “We do not require any money. India is a bird of gold. We have learned ‘giving’ not ‘taking.’ We cannot attain God as long as we have got attachments for these two: (1) gold and (2) women (in Hindi, ‘Kamini’). No two swords can be put into one sheath; the more we sacrifice (tyaga), the more we gain…. ”

IF YOU HAVE ENOUGH FAITH YOU CAN GIVE UP MONEY AND POSSESSIONS. GOD WILL GIVE YOU EVERYTHING YOU NEED FOR YOUR SPIRITUAL DEVELOPMENT.

A tiny, gnarled old woman came for Maharajji’s darshan. She was, I think, from one of the local farms. Tottering up onto the porch, she touched Maharajji’s feet with her head and sat down. Then with much difficulty she unknotted the end of her sari and took from it some crumpled rupee notes and pushed them across the tucket toward Maharajji. I had never seen anyone give Maharajji money and I watched with some discomfort, for this woman was obviously as poor as the proverbial church mouse. Maharajji pushed the money back at her and indicated that she was to take it back. With no expression she reached for the money and started to put it back into her sari. The full meaning of the situation escaped me, for I understood too little of the culture to appreciate what was happening.

But then Maharajji seemed to have a second thought and demanded the money back from the Ma. Again with arthritic hands she untied the corner of the sari and handed him the bills. There were two one-rupee notes and one two-rupee note. (Four rupees were worth about forty US cents). Maharajji took them from her and immediately handed them to me. I didn’t know what to do. Here I was a “rich Westerner” (in India even poor Westerners are “rich Westerners” because of the relative values of the economies), with a private car (a rare luxury in India) and traveler’s checks. I just couldn’t accept this money. But when I tried to hand it back to the woman, Maharajji refused to allow it. I was told to keep it.

That night I put the four rupees on my puja table and reflected on them for a long time, but no great clarity was forthcoming. Later, one Indian devotee told me that I should hold onto the money, that if I did I would never want.

During that period an old Sikh couple had taken to visiting me at the hotel. They ran a tiny dried fruit store and were obviously very poor. Yet each time they came they brought me offerings of dried fruit, kneeled at my feet, and told me in great detail of their hardships in life. Why they had taken it into their heads that I could help them, spiritually or materially, I have no idea, but they kept coming. Then one day they told me that due to illness they must leave this region and move to the plains, where their financial predicament was going to be, if anything, more precarious. I felt that I wanted to give them something for their journey, but nothing came immediately to mind. Then I thought of the four rupees. I got one of the rupees and explained to them how it had come to me and that if they held on to it, everything would be all right with them. They left Nainital and I have not heard from them since. I still have three of the rupees. And thus far I’ve always had more than enough money. (R.D.)

DS said that he had always kept all the money Maharajji gave him, which amounted at one time to over two hundred rupees. Then somehow it was all stolen from his home. After that, whenever Maharajji gave him money it would be with the added admonition not to lose it. DS took out an envelope from a hiding place in his home and showed it to me. Inside was a small packet of rupee notes—tens, fives, twos, and ones—all of them stapled together many times over.

Maharajji pulled two rupees out from underneath his blanket and stuck them in my hand. He said something I couldn’t hear when he put them in my hand. I didn’t have them very long. I gave one to the Tibetan mandir (temple) in Manali, and the other I gave to a beggar.

I don’t know where he would get it, but he used to give me money. One time he was about to give me a great deal of money when I asked why, since I was earning enough, and he was a sadhu. If he gave me this surplus, then I might take it to go to the movies or go drinking. “Would you like that?” I asked him.

No, he said, and so he didn’t give me the money.

Once he gave me five rupees, and my sister thirty, which he said to keep with us. She kept the money but I gave mine away. I told him I would not keep these things.

Once, shortly before he disappeared, he gave me a hundred-rupee note. I told him I didn’t want it, but he said I should keep it; and when I again refused, he said, Okay, then I’ll keep it.” I don’t know how it happened, but after I left I found the one hundred-rupee note in my pocket.

During Swami N’s first darshan, Maharajji gave him ten one-rupee notes and told him to keep them as prasad. Swami kept the money in his purse, and from that day he has never been without sufficient money. His purse always has more than enough.

He gave me the two rupees. That was the only time he gave me anything apart from the laddus and prasad. I remember the two rupees distinctly, being astonished and worried because I didn’t know what to do with them. “What am I going to do now?” I thought. “What’s this money for?”

One day this man came to my house to have the darshan of a sadhu staying there. He spotted the photo of Maharajji that I keep there and said, “I know him. I know him,” and began to relate the story of his darshan with Maharajji.

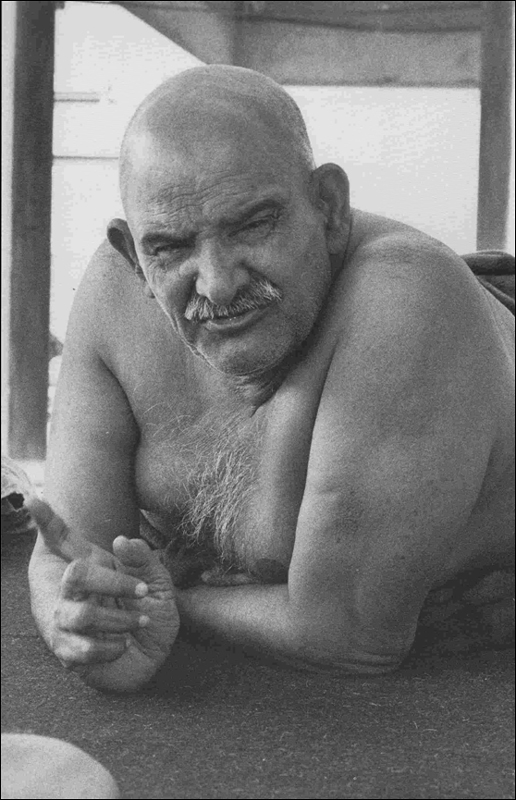

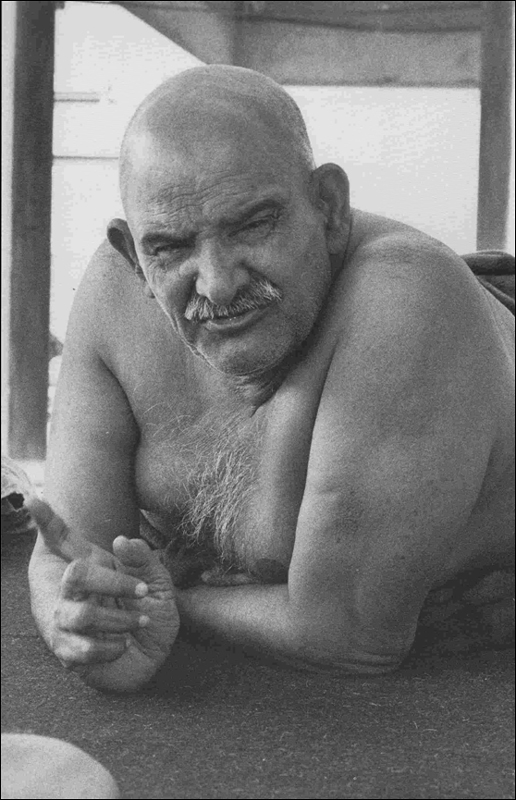

He had been a young boy and very bitter at the world. One day he had gone to an old Shiva temple, and there in the compound Maharajji was sleeping. (The man gave an accurate description of Maharajji lying on the ground, wearing only a dhoti, and covered with a plaid blanket.) Maharajji had sat up and at once commanded the boy to bring some milk for him. The boy became angry at this baba for treating him like this. Maharajji pulled thirty rupees from under his blanket and told him to buy the milk with it. The boy ran out with the money and came back with half a kilo or so of milk. He pocketed the change and Maharajji never asked for it. He left with the money, which was much needed by his family. Maharajji knew better than to ask if he needed money or to give him a gift. The boy was too proud, so Maharajji tricked him into taking the money.

One time when we were all living in Kainchi Valley, Balaram asked Maharajji if we should request money from anyone to fix up the house. Maharajji said yes, that we should write to Harinam. I wrote the letter on an aerogram, which we showed to Maharajji before sending. Balaram folded it up, sealed it, and mailed it, and when Harinam replied, he said he’d send money and that he thought it had been nice of us to enclose the two-rupee note, but why had we put it there? We had not put any two-rupee note in that letter, and as far as I know, Maharajji never mentioned it. This was one of the little money tricks he liked to play.

MONEY IS NEVER A PROBLEM. THE DIFFICULTY IS IN THE CORRECT USE OF IT. LAKHS AND CRORES (LARGE AMOUNTS) OF RUPEES WOULD COME EASILY IF THEY WERE GOING TO BE PUT TO WISE USE.

Recently I was confronted with the problem of which medium to use for the construction of the meditation hall at Maharajji’s temple near Delhi. On the way there one day I met two men who introduced themselves as architects. I became interested, so I asked what sort of work they were doing. They replied that they were designing a five-star hotel in Patna. This told me that they must be good, so I asked them to stop for ten minutes at the temple to give me their advice on my problem. When they saw the temple and the pictures of Maharajji one man exclaimed, “So this is where the ashram is! I know him. He is the cause of my life!” I asked him to explain what he meant.

He said that when he was young, his family had taken him to see Maharajji. Maharajji had turned to him and asked, “What’s the problem? What do you want?” and the boy had answered, “Money.”

Maharajji then pulled a ten-rupee note out from under his blanket. Everyone laughed at the incident and after a while they all left. The boy’s family then suggested that they all go to the movies with the prasad money, but he refused to part with it and has kept it to this day. Money has come to him whenever he needs it. If he has needed ten thousand rupees by evening time, it has been put into his hands by the afternoon—all this from the faith derived from only one or two darshans.

The architect volunteered to help design the meditation building free of charge, in thanks to Maharajji.

Once when V was to return home, he found that he was a little short of money, so he made arrangements to borrow two hundred rupees and then went to Kainchi to pay his respects to Maharajji before leaving. Maharajji blessed him and sent him out. Then he called V back and said, “You’ve changed your program. You’re not going to Lucknow. You’re out of money. You are short two hundred rupees.” Maharajji called for the pujari who had the keys to the temple box, but the pujari was at the bazaar, along with the keys. Maharajji sent V to go and pray to Hanuman, then immediately called him back.

Maharajji reached inside his blanket and pulled out two hundred rupees. V asked how he got the money, and Maharajji said that when V went out to see Hanuman, someone came into the room and gave it to him.

When I was young I had no money with me, but Maharajji kept insisting I had plenty. My father and I were in the vegetable business, and every time I would bring vegetables, the full price was never paid. What Maharajji gave me I accepted, but I just didn’t tell my father because he would be angry. But I never could be sure how accounts balanced. Once I even said, “Maharajji, this is very little money that is coming for the food I brought.”

Maharajji said, “It’s all right. Take it.” Another time he said, “You shall have a house.” And later, “Give it all away.” Now I have a house and two shops. I’m a rich man, due to Maharajji.

KK had prepared a pattal (leaf plate) of sliced fruit for him, and as he was talking to Maharajji, he held out the fruit and Maharajji would eat a little bit. Maharajji called me over from where we Westerners were sitting. “Bring that Peter over here,” he said. (This before he’d given me my name.) He said, “What would you give me?”

I said, “Baba, I’d give you everything I have.” This had something to do with his previous conversation, when he’d called me over to make a point in the conversation he was having with these Indians.

He turned to the Indians to say something like, “Do you see this? Did you hear that?” Then he scooped up the apples from the pattal that KK was holding, and with his hands he lowered them into my hands and said, “With these apples, I’m going to give you many dollars.” He said “dollars” in English. (The Indians later said to me, “Do you know what he said? Do you know the blessing you just got?!”)

I answered him, saying, “Maharajji, what kind of wealth? All I want is spiritual wealth.”

And he said, “Nahin! Bohut dollar (No, many dollars)! Jao.”

You can see how that blessing is not inappropriate to my becoming a doctor, since everyone thinks that doctors get a lot of money. If I do become wealthy as Maharajji said, what I would like to do is start some businesses that would employ a lot of the satsang (fellow devotees).

MONEY IS AN OBSTACLE. ONE IN COMMUNION WITH GOD NEEDS NO MONEY.

There was a shopkeeper in Kainchi whose daughter was to get married soon, but he did not have enough money for the wedding. Maharajji told him not to worry; in three days he would get plenty of money. Three days later there was a landslide and the road was blocked, and all cars and trucks had to stop there. Whatever grains and foodstuffs that he had gathered in preparation for the marriage ceremony were consumed by these people, and in this way he got a lot of money.

Maharajji used to stay in Kanpur for a few days at a time. There lived one of the wealthiest men in India, whose whole family were devotees. Maharajji had never come to their home, a palatial mansion, and on one of his visits they insisted he come. He came with a crowd of people. The family did puja and then served a magnificent feast of many rare delicacies. They tried to instruct Maharajji as to what to eat first, followed by this, then that. Maharajji put everything—sweets, curries, fruits, vegetables—into one bowl, mixed them together, and ate. When he was finished he took the wealthy man’s driver, of whom he was very fond (who had also driven him to Amarkantak, a trip of many days), and drove away. Maharajji said to him, “Now let’s go to your house.”

The driver, who lived in a slum hut in a very poor section of Kanpur, couldn’t believe Maharajji, but he was insistent. Upon reaching there, Maharajji said, “I’m hungry. Bring me food.” Being very poor, they had nothing in the house. The family had already eaten and preparing rotis would take time. Maharajji said, “No, there’s gur (crude brown sugar) in that jar. Bring it to me!” They went and found the gur and Maharajji relished it.

I once complained that Maharajji only visited the rich; then he took me to live for several days with the cobbler in a poor small room. Although we were very cramped, Maharajji was happy.

He seemed to be happiest among the poor people. With them he would get a soft, happy quality in his face.

Maharajji said to a complaining devotee, “You don’t have money in your destiny, so what can I do?”

A rich man who had come for darshan was asking Maharajji to give him his blessings in order that he get wealthy. This is what Maharajji said: “Look, you’re already stinking rich. I’m not going to give you any blessings that you get rich.” This man wanted blessings to be as rich as Tata (one of the richest men in India).

Maharajji started to tell the story of Birla (another very wealthy Indian). Birla had been an ordinary guy who also had gone to his guru and asked to be made the richest man in India. His guru had told Birla to wait and serve, so Birla started serving his guru—cleaning the shit, washing the dhotis, this and that. Years and years passed but still his guru made no mention of giving him the blessing of bottomless wealth. For ten years Birla had faithfully served his guru, never again mentioning his desire.

One day the guru called Birla in and said, “Okay. Here it is,” and he took a lota and urinated in it. “Take this lota of piss. Cover it and get on the train to Calcutta. When you get to Calcutta, get off the train. When you get off the train, drink the piss. This is the blessing.”

So Birla faithfully obeyed. When he got to Calcutta, he drank the urine, which by that time had miraculously transformed itself into nectar, so I presume he didn’t have to gag. One thing led to another, and he became the richest man in India.

After hearing this story, the rich man said, “Maharajji, Maharajji! Let me drink your piss!”

“Nay, nay, nay, nay. I won’t give you any piss.”

“Anything, anything! Give me your piss!”

And Maharajji said, “Oh, no. I won’t bless you for wealth. I will only bless your grandsons. I won’t bless you. You’ve already got enough.”

“Okay, okay. Do it. Do it. Anything.”

This went on until Maharajji finally relented and said, “I won’t give you any urine. I’ll give you a piece of roti.” Maharajji then asked us, “Has anybody got any roti? Anybody got any roti?” I had earlier gotten a little piece of roti; I had taken a bite out of it and kept the rest in my hand. I gave my half-eaten piece to Maharajji, who blessed it and gave it to the rich man.

He exclaimed, “Oh, this is the greatest thing.” He was delighted.

Then Maharajji went on to something else, and while he was talking, another devotee turned to the rich man and told him the bread was juth (unclean) because I had eaten some of it. All of this going on behind Maharajji’s back. The rich man gave the roti back to me—roti blessed with millionaire-hood! I ate it!

Maharajji always told me to spend my money: “Spend it. Don’t save it. Keep the money flowing. Give it to the needy. Spend it.”

When I first met Maharajji I was out of money, and my plane ticket back to the West was to expire within a week. But believing that “Clinging to money is a lack of faith in God,” I stayed on. Nearly two years passed, during which time all was provided for me, but I never actually had any money. Then I found out that I had inherited a thousand dollars. I immediately offered it all to Maharajji in my heart and had the money sent to India. As I was leaving for Delhi to pick it up, I asked what I could bring Maharajji. He asked for twenty brooms and several tins of milk powder, and as I was walking out the door he called me back in and asked me to bring him a blanket. The blanket was the first thing I bought with the money.

When I returned to Kainchi, every day Maharajji would ask me for some amount of money or other, as would the Westerners. I would always give. It was not my money. Then, when it was nearly gone, all but one twenty-dollar traveler’s check, Maharajji told me not to cash it. About a week later he sent me to Nepal and asked me to stay there for four months.

Of course I now had no money. He asked a few people to give me money—altogether maybe five hundred rupees—and sent me off. In Nepal, while traveling with a companion, I lost all my rupees. We knew it was Maharajji’s doing, and as we walked back to the hostel a small boy came beaming up to us, asking if everything was all right, just the way Maharajji does. We both felt it was he. At the hostel I rediscovered the twenty dollars, and with that we returned to Kathmandu. It was in Kathmandu that we learned Maharajji had left his body.

MONEY SHOULD BE USED TO HELP OTHERS.

During the summer in Kausani, one of the Western devotees told me that he wanted to give some money to Maharajji. He had earned and inherited quite a bit of money and had been very generous in a quiet way, helping out various members of the satsang who had used up their own funds. He asked me how much I thought he ought to give to Maharajji.

“Why don’t you give all your money to Maharajji?” I suggested. “Since you say that your only concern is that your money be used consciously—and if Maharajji is your guru you must accept that he is more conscious than you are—obviously he should decide what to do with your money. If he thinks you should be responsible for it, he’ll give it back to you.”

But the devotee didn’t see it that way and so he gave Maharajji about two thousand dollars. Now in our daily visits Maharajji kept querying me as to what I thought he should do with the money—Did I think it should be returned to the devotee or not?

Although I didn’t understand the implications of any of this, I urged Maharajji to return the money to the devotee, mainly, I think, because I felt the gift reflected a lack of faith. The money was returned at that time, but I don’t know what finally happened ….(R.D.)

I do. The following year, when this devotee was about to leave India, he wanted to try once again to give the money to Maharajji. In Delhi he changed his remaining money into rupees and gave it to me, as I was staying in India. I agreed to try to give the money once again and, if it was not accepted, to eventually return it to him in America. I took the rather large bundle of rupees back up to Kainchi and discussed the matter privately with Dada. Some days later as the satsang were about to leave for the bus back to Nainital, Dada announced that I was to remain in Kainchi for the night. This produced quite a stir, since it seemed that some mysterious special privilege was being conspicuously bestowed. I was no less mystified than anyone else, as by now I was used to carrying the bundle of rupees around and had virtually forgotten them. After evening darshan and supper, when we had all retired to rooms for the night, Dada appeared, flashlight in hand, to escort me down to the darkened temple. There, it seemed to me that I heard the soft breathing of sleeping Hanumanji while I slowly stuffed rupees through the narrow slot of the donation box.

“Serve the poor,” Maharajji said.

“Who is poor, Maharajji?”

“Everyone is poor before Christ.

It was the mela. Maharajji had a tent there and prasad was being distributed all the time to all the devotees who came. People were preparing food from eight in the morning until two or three in the afternoon. The biggest millionaire in India arrived, and Maharajji immediately yelled, “Go away! I don’t want to see your face! Get out! Go away!”

The man said, “Well Maharajji, I have come with these two bags of flour for you to give to the poor, in your bhandara. Please accept.”

Maharajji yelled out, “No! Go away! Don’t show me your face. Don’t come here.”

When that man still didn’t go away, Maharajji stood up and went away himself. Still the man didn’t go. He followed Maharajji saying, “Oh Maharajji, give me some teachings. What should I do?”

Maharajji replied, “What teachings should I give you? Will you follow me? If I give you teachings, will you follow me?”

The man kept mum.

Maharajji said to him, “Whatever wealth you have, you give it to the poor. This is my teaching. Will you follow it?”

GIVE UP MONEY, AND ALL WEALTH IS YOURS.

Again and again Maharajji reiterated that one should not be attached to money, because it just causes trouble. He was fond of telling the story of a man who made much money, whose son became so greedy for the money that he came to his father with a gun demanding some of it. Then the father said,

“Take it all.”

I had seen again and again in America how much trouble money made in families and what greed and bitterness could exist between a wealthy father and his children—all over money. Although I didn’t feel that way toward my father, I wasn’t oblivious to the fact that someday, at his death, I would inherit much money. Then one day Maharajji called me to him and asked, “Your father has much money?”

“Yes, Maharajji.”

“He is going to leave it to you?”

“A share of it he will leave to me.” I thought of the pride my father had in remembering his own earlier financial hardships, due in part to his father’s untimely death, and how he had built financial security so none of his children would ever have to face what he faced.

“You are not to accept your inheritance.”

I had never even considered that. Knowing that I would not have personal use of this money has affected me much to the good. Though I never told my father that I would not accept my share of his inheritance, something changed between us, and his trust in me grew and grew. Ultimately he gave me his power of attorney and made me the executor of his estate. After he died I found it very easy to let go of the share of the money that he had earmarked for me. (R.D.)

CLINGING TO MONEY IS A LACK OF FAITH IN GOD.

J’s brother was told by Maharajji to give all his money away. He said, “No, Maharajji, what about my family?”

Maharajji said, “You’ll have so much more. Give it all to me. Give it to me.”

Sometimes Maharajji would send a message to Haldwani asking J’s brother to get him railroad tickets, but the brother would hide so he wouldn’t have to get the tickets. Finally Maharajji said, “I’m making my grace toward J. You are greedy. Now you’ll suffer.” At the time, J was poor and all the rest of the brothers were rich. But now J is doing well and the one brother has lost his business and has nothing.

MONEY BRINGS ANXIETIES.

In earlier years Maharajji had spent time wandering with a sadhu. The sadhu started to hold on to money and entrusted some to one of his devotees to hold for him. Maharajji came to the devotee and persuaded him to use half the money for his daughter’s dowry. When the sadhu heard this he was angry with Maharajji. Then Maharajji is supposed to have said, “You are ruining yourself. Get rid of it all.” The sadhu saw that he had indeed gotten caught, and he started a huge fire and burned all his possessions. Maharajji said of him, he was a good sanyasi.

One day when I was alone with Maharajji and a translator, Maharajji was warning me about money. “Money is all right for a grihastha (householder) but it is worst for a yogi. Money is your enemy. You should not touch money.”

I asked him if it wasn’t all right to keep enough money for one’s daily needs. He said that that was all right: “Keep only as much money as is necessary for your needs and distribute the rest.” Well, such an instruction gave me all the latitude I needed, for who defines “needs?”

Soon Maharajji returned to our earlier conversation about my having money.

“Money is your enemy. You should not touch it.”

“But, Maharajji, isn’t it all right to keep enough for daily needs?” But this time he answered, “No! Money should go around a saint, not through him.” He had just filled in the loophole.

When I returned to the hotel that night I reflected that these new instructions required some action, at least the beginning of some experiments with money, so I decided to try for a time literally not to touch money. By not having money in my pocket there would be the opportunity, each time I would usually reach into that pocket, to become conscious in the use of money. But on the other hand, I reasoned, I didn’t want to become financially dependent on others. The Indians for the most part could not afford it and neither could most of the Westerners. So, as a first experiment, I turned over to one of the Westerners all my money, and he became my “bag man.” He would pay bus fares and so forth. While I appreciated that this was not the spirit of Maharajji’s instruction, it would at least adhere to the letter of the law, “You should not touch money.” Of course, I knew Maharajji meant something more. Over the years as a result of his instruction, I still physically deal with money, but I’ve come to “touch” money with my mind less and less. (R.D.)

A SAINT NEVER ACCEPTS MONEY.

When the engagement of one family’s son was settled, they brought sweets to Maharajji. Maharajji said, “I was just remembering you. Good you came. So your son is engaged, and you got money from your in-laws. Uncles and aunts each got a hundred. What about me? How about a hundred?”

I first heard Maharajji’s name about ten years ago in Kanpur. They said that he was a very high-class mahatma and that he knew everything. A friend told me of his darshan with Maharajji: “I have seen him. He has some power or some ghost in his hand. This is how he knows everything. It’s not a spiritual power but some ghost or something.”

There were some influential businessmen who went to Maharajji, and he told them to buy a certain type of goods and sell them. In one day, each of the three men made twenty-five or thirty thousand rupees. They thought that if they stayed near Maharajji, he would let them know how the market was going to behave. They went to him and he asked, “Did you make some money?” Each answered with the amount he had made and then asked Maharajji for further instructions.

Maharajji said to a devotee, “What will be the result if everyone comes for money? These Kanpur industrialists are bad. They’ll give me trouble.” Then Maharajji said to one, “Okay. You’ve got thirty thousand rupees. Tomorrow, bring three thousand for me.” To another he said, “You bring fifteen hundred.” To the third, “You bring twelve hundred.” They all agreed but never returned, thinking he was corrupt. Maharajji was not anxious about money, but he wanted to have his life free from those speculators. Of a fourth man, a relative of mine, Maharajji asked that he bring nine hundred rupees. The next day the man returned. Maharajji asked, “Did you bring the money?”

“No, Maharajji, I haven’t brought it,” he replied.

“Why?”

“Maharajji, I come here to take something, not to give.”

“Oh, you come to take, not to give. All right, come on. I don’t want money. Let those other people not come.” My relative became a devotee.

Once the Queen of Nepal came, as her husband was very much devoted to Maharajji. She presented Maharajji with many things, but he said, “No, distribute it among the people.” He grabbed me and said of her, “There is big money there. Shall we get some?”

I said, “Yes.” We both laughed. Such was his humor. Usually people only report Maharajji as saying that he never touches money.

Maharajji once said, “The money you earn should be straight. What do you want—to bring a bad name to me?”

A sadhu who was visiting the temple upbraided Maharajji for having temples and being attached to possessions. He sat on the tucket with Maharajji and was very fierce. Maharajji just listened and kept the devotees who were present quiet. A little later the sadhu brought out a shaligram, a special stone used in doing puja to Shiva. Maharajji said to the sadhu. “You will give it to me?”

“But Maharajji, I need it for my puja.”

Then playing into the sadhu’s accusation that Maharajji was a materialist, Maharajji said, “You will sell it to me?”

“Oh no,” said the sadhu. But Maharajji finally convinced the sadhu to sell it to him for forty rupees. And the exchange took place.

Then Maharajji said, “Give me your money.”

The sadhu took out the forty rupees and begrudgingly gave them to Maharajji, protesting all the while that this was all the money he had, so how would he live? Maharajji took the rupee notes and threw them into the brazier that was burning before them. The notes were consumed. The sadhu was very upset and admonished Maharajji for burning the money and protested that now he would starve, and so on.

At this point Maharajji said, “Oh, I didn’t realize you were so attached to the money.” And with that he took a chimpter (set of tongs), reached into the fire, and began pulling new, unburned rupee notes from the fire until he had returned all the rupees to the sadhu. After that the sadhu did not sit on Maharajji’s tucket any longer—but at his feet.

ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD IS MINE. EVEN THE MONEY IN AMERICA.