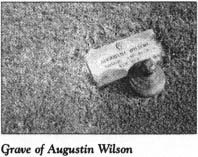

Cheraw, Bennettsville, Blenheim, Darlington, Bishopville, Camden

Total mileage: approximately 174 miles.

THIS TOUR MAKES ITS WAY through a five-county area in the sandhills of northern South Carolina. Eighteenth-century settlers put down roots along three major rivers in this area—the Great Pee Dee, the Lynches, and the Wateree. It was here that the cause of independence suffered one of its greatest setbacks during the entire war.

The tour begins at the junction of U.S. 52 Business (Second Street) and Church Street in the old Chesterfield County town of Cheraw. Go east on Church Street for two blocks to Old St. David’s Episcopal Church. This picturesque white frame structure is adorned with a towering belfry. Completed in 1774, it was the last church built in South Carolina under the authority of King George III.

No longer used on a regular basis, the church has been renovated and restored by local and state agencies. The central portion of the sanctuary is little changed from the time it was built. Box pews face a raised pulpit of polished black walnut. Visitors wishing to see the interior should inquire at the Cheraw Visitors Bureau.

Because of its location on the Pee Dee River, Cheraw was a strategic town throughout the Revolution. Both armies held it at various times during the conflict. Accordingly, the church was used to house American and British troops. Soldiers of the South Carolina militia were quartered here at one time. In the summer of 1780, the Seventy-first Highlander Regiment from Lord Cornwallis’s army lived in the church and used it as a hospital.

During their stay here, many of the British troops fell ill with smallpox. Fifty of them died and were buried in an unmarked grave in the front churchyard. British officers were buried in separate brick-covered graves. The sprawling church cemetery that surrounds the stately building holds the graves of many Revolutionary War veterans from both armies.

Following the war, the church fell on hard times, as all things associated with Great Britain were held in contempt. In the early nineteenth century, the Baptists and the Presbyterians began to use the old Anglican church. At times, ministers of the two denominations actually raced to the church to claim the pulpit. On one particular Sunday in 1824, the Baptists initially won the contest, to the dismay of the Presbyterians. To gain possession for themselves, the Presbyterians loaded and fired an old Revolutionary War cannon. Alarmed by the blast, the Baptist minister abruptly ended his service, and the congregation fled.

Several years later, the Episcopalians claimed the building. In a moment of retrospection, the Presbyterian minister responsible for the cannon blast remarked wistfully, “While the lion and the unicorn were fighting for the crown, up came the puppy dog and knocked them down.”

A state historical marker for the church stands nearby.

Turn around and proceed three blocks southwest on Church Street to Third Street. Turn right and drive two blocks north to Market Street. Located here is the Town Green of old Cheraw.

Settled around 1752 by Welsh immigrants from Pennsylvania, Cheraw quickly grew in importance because of its location on the navigable Pee Dee 100 miles inland from the port of Georgetown. When the Revolution erupted, both armies operated in and around the town. When the British established their major base at Camden in May 1780, they put an outpost at Cheraw a month later. The British occupation lasted five months.

Housed in a small brick Greek Revival building on the Town Green is the Lyceum Museum, which contains exhibits related to the long history of Cheraw and the surrounding Pee Dee area. Constructed in 1820, the handsome structure was originally used as a library and lecture hall.

Continue north on Third Street to Kershaw Street. Located at the southwestern corner of this intersection at 235 Third Street, the McKay House is one of more than fifty antebellum homes in Cheraw. This square two-story frame dwelling, constructed in 1820, was used to entertain the Marquis de Lafayette during his triumphant visit to the United States in 1825.

Return to the intersection of Third and Market. Turn right on Market and follow it for six blocks to where the road forks. Take the left fork (U.S. 1/U.S. 52) and drive south for 5.1 miles to the community of Cash, where you’ll see a state historical marker honoring Captain Thomas Ellerbe. Ellerbe (1742–1802) was selected in 1768 to serve as a commissioner in the building of St. David’s Church. During the Revolution, he was an officer under the command of the legendary Francis Marion.

Turn around and proceed 3 miles on U.S. 52 to Juniper Road. Located nearby is Red Hill Cemetery, which contains the grave of Captain Ellerbe; the cemetery is located on private property.

Continue north on U.S. 52 for 2.9 miles to U.S. 1/S.C. 9 in Cheraw and turn right. It is 0.8 mile to the Marlboro County line at the Pee Dee River; continue 1.1 miles on U.S. 1/S.C. 9 to Wallace. Turn left to follow U.S. 1; proceed north for 6.1 miles to S.R. 35-266, where you’ll see a state historical marker for Pegues Place, the location of a cartel for the exchange of prisoners during the Revolution.

To see the site, turn left on S.R. 35-266 and follow it for 1.1 miles to its terminus. Here stands the two-story frame house that belonged to Claudius Pegues when officials from the British and American armies met on May 3, 1781, to execute an agreement for the release of prisoners of war. Lieutenant Colonel Edward Carrington represented Major General Nathanael Greene at the conference, and Captain Frederick Cornwallis appeared for his famous cousin.

Return to U.S. 1. Turn right and proceed 5.8 miles to Wallace Baptist Church, on the eastern side of the highway. A state historical marker notes the site where Nathanael Greene and his thousand-man army camped from December 20, 1780, to January 28, 1781.

After assuming the command of Horatio Gates in early December 1780, Greene split his army, giving a portion to General Daniel Morgan, who promptly used it to battle Tarleton at Cowpens. Meanwhile, Greene camped here at a site selected by his Polish engineer, Colonel Thaddeus Kosciuszko.

Continue south on U.S. 1 for 0.3 mile to S.C. 9 in Wallace. Turn left and drive southeast for 12.3 miles to Main Street in Bennettsville, the county seat. Turn left on Main and go two blocks east to the Marlboro County Courthouse.

On the courthouse grounds is a monument to the Marlboro County men who fought in the Revolution. For much of the conflict, a virtual state of civil war existed in the county. As one resident put it, “Tories preyed on Whigs, and Whigs chastised Tories.” For example, a Patriot by the name of Reed was discovered while at home on leave. When a band of Tories encircled his house, Reed secreted himself in the loft. His adversaries ordered him to descend and surrender, or they would burn the house over his head. Fearful that his family would have no home, the Patriot came down. As soon as he reached the door, the Tory guns blazed, killing him instantly. In retaliation, Patriot raiders rode throughout the area terrorizing Tories.

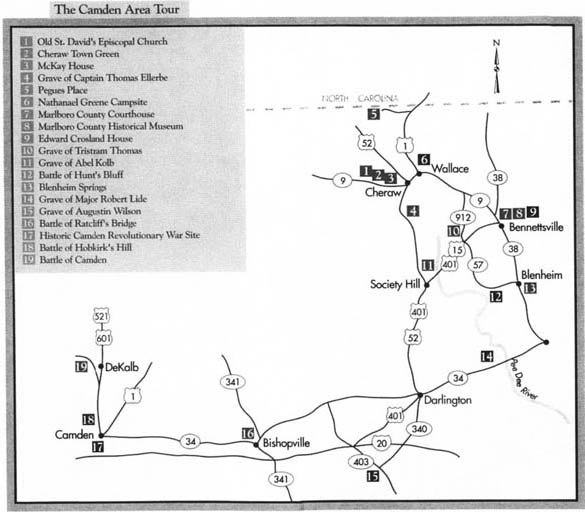

Located at 119 South Marlboro Street across from the courthouse is the Jennings Brown House, which dates to around 1826. Headquartered in the home is the Marlboro County Historical Museum, which chronicles the history of the county through displays of memorabilia.

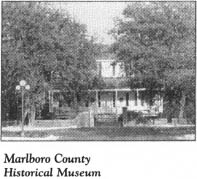

Continue one block east on Main to Parsonage Street, turn right, and drive two blocks to the Edward Crosland House, at 204 Parsonage. This small, unassuming frame house, constructed about 1800, is the oldest home in Bennettsville. It was the residence of English-born hero Edward Crosland, who served the American cause as a soldier in the Revolutionary War. A state historical marker for the house stands at the roadside.

Return to Main Street, turn left, and drive two blocks to Broad Street (S.C. 9/S.C. 38). Turn left, proceed nine blocks south to U.S. 15/U.S. 401, turn right, and drive west for 2.7 miles to S.R. 35-43. Turn right and go 2.3 miles to S.C. 912, then turn right and head north for 1.6 miles to S.R. 35-209, where you’ll see a state historical marker for the nearby grave of Tristram Thomas.

To see the burial site of this Revolutionary War officer, turn left into the entrance to Saw Mill Baptist Church. Thomas’s grave is prominent near the church.

Born of Welsh parents in Maryland, Thomas and several of his brothers settled in the Pee Dee region before the Revolution. During the fight for independence, he served the Patriot cause as a major. At the Battle of Hunt’s Bluff (covered later in this tour) on July 25, 1780, American militia commanded by Major Thomas won a significant victory.

Following the war, Thomas played a key role in local and state affairs. The original Marlboro County Courthouse, which stood nearby, was built on a two-acre tract given by Thomas for that purpose. He served in the early legislatures of the new state and was appointed general of the South Carolina militia.

Turn around and proceed south on S.C. 912 for 4 miles to U.S. 15/U.S. 401, where you’ll notice a state historical marker for the Old River Road. In the eighteenth century, this principal trade route crossed what is now U.S. 15 as it followed the Great Pee Dee from Georgetown to the upstate. Patriot forces traveled the route on a regular basis during the war.

The original county courthouse was located 1 mile north of the current tour stop.

Turn right and drive southwest on U.S. 15/U.S. 401 for 5.4 miles to S.R. 35-167. A state historical marker along the highway tells of the wartime murder of Abel Kolb, one of the area’s most distinguished Patriots.

To see Kolb’s grave, turn right on S.R. 35-167 and drive 0.6 mile. On the left, you’ll see the remains of the old Welsh Neck Cemetery overlooking the Great Pee Dee. Buried here are settlers who established farms and plantations along the river. Of the few remaining marked graves at the site, the most prominent is that of Abel Kolb. Kolb’s two-story brick home was located a short distance from the current stop.

From the onset of the Revolution, Kolb was an ardent Patriot and a moving spirit behind the local support for the cause. He served as a lieutenant colonel under Francis Marion. When American troops from the Pee Dee hurried to Charleston in 1780 to aid the beleaguered port city, Kolb commanded a regiment with great distinction.

After the fall of Charleston, Kolb’s services were needed in the Pee Dee. Over the next year, he led a number of successful expeditions against area Tories. It was this service that led to his murder.

Satisfied that he had subdued the local support for the Crown, Lieutenant Colonel Kolb discharged his soldiers and headed home. While he was on his journey, Captain Joseph Jones and a group of fifty Tories assembled to devise a plan of revenge against Kolb. For Jones and his men, the only revenge that could satisfy was death.

They arrived at Kolb’s plantation under cover of darkness. Among those inside the home were Kolb, his wife, and his eight-year-old daughter. Two of Kolb’s staff members were elsewhere on the plantation. These men were summarily executed by Captain Jones’s soldiers. What happened next was subsequently related by Kolb’s young daughter, Ann, an eyewitness to the violence.

Captain Jones demanded that Mrs. Kolb produce her husband. He promised that no harm would come to Lieutenant Colonel Kolb, but that the house would be torched if she refused. She complied and came walking down the steps with her arms around her spouse. No sooner had their feet touched the porch than a Tory soldier fired a bullet that hit Kolb’s heart. The Tories then burned the house.

The D.A.R. monument at the grave relates a different version of the story: “Lurking Tories fail[ed] to decoy him from his house which stood nearby. The Tories set fire to it, and escaping from the fire he was shot.”

At present, Kolb’s grave site is in a very poor state of repair, though its setting on the river is quiet and picturesque.

Well into this century, the cellar walls of the family’s house could be seen near the river.

Return to U.S. 15/U.S. 401. Turn left, drive northeast for 5.5 miles to S.R. 35-57, turn right, and proceed south for 7.3 miles to S.R. 35-611, where you’ll see a state historical marker for the Battle of Hunt’s Bluff.

To see the site of the battle, turn right on S.R. 35-611 and follow it for 0.3 mile to its terminus on the banks of the Great Pee Dee River.

At this sharp bend in the river, you’ll have a view up and down the great waterway much like the one enjoyed by Major Tristram Thomas and his band of Patriots when they tricked a British flotilla into submission here on July 25, 1780.

Soon after the British captured Charleston on May 12, 1780, they formulated plans to strengthen the Crown’s position in other parts of the state. Because of an inordinate amount of sickness among the garrison at Cheraw, Lord Rawdon ordered the consolidation of that post with the much stronger base at Camden. To move the sick and wounded overland from Cheraw to Camden would have been difficult at best. Convinced that the banks of the Pee Dee were free of Patriot forces, Colonel Archibald McArthur, the commander of British forces at Cheraw, decided to move the invalids by boat to Georgetown for recuperation.

This hospital flotilla was commanded by Colonel Henry Mills, a local physician who had once been a stalwart supporter of the cause of independence. Mills had served in the Provincial Congress in 1776, but after American forces suffered a series of early setbacks, he had switched sides and become a Tory.

Upon learning of the British voyage down the river, local Patriots assembled at the present tour stop. Major Tristram Thomas selected this spot because it was an excellent place to set up a battery of field guns to control river passage. However, Thomas’s strategy had one serious flaw: he had no artillery, and his soldiers’ small arms could do little to impede the flotilla.

As a substitute for heavy guns, Major Thomas used ingenuity. He reasoned that if the British sailors believed they were looking at cannon on the riverbanks, they would surrender. Thus, he employed the old “Quaker Cannon Trick,” so named because of the pacifist nature of the Society of Friends. No sooner had Thomas given the order than his soldiers turned into woodsmen, chopping down trees and hewing their trunks into would-be artillery pieces. In little time, the riverbanks at the current tour stop were fortified with a formidable arsenal of wood.

All was ready when Mills’s convoy came into sight on its slow voyage down the river. Patriots poured out of their hiding places and pretended to load their big guns for firing. The Americans shouted to Mills that the convoy must surrender or it would be blasted out of the water.

Without hesitation, the British acceded. In the confusion that followed, Colonel Mills somehow escaped. Nevertheless, the Americans took the entire convoy, the remainder of the men aboard, and a British supply boat that happened by as the surrender was being effected.

Return to S.R. 35-57, turn right, and proceed 4.3 miles to the intersection with S.C. 38 and S.R. 35-49 in the town of Blenheim. A nearby state historical marker details the history of this community, which was named for Blenheim Palace in England, the home of the duke of Marlborough, the man for whom Marlboro County was named.

Turn east on to S.R. 35-49 and drive 0.3 mile to Blenheim Presbyterian Church. Turn right on S.R. 35-603 just beyond the church and drive 0.1 mile to Blenheim Springs, where visitors are invited to partake of the water from the famous mineral springs.

Local Patriot James Spears discovered the springs while trying to escape Tories in 1781. Since that time, people have traveled far and wide to sample the famous water.

Blenheim Ginger Ale, a drink with its unique spicy taste, has long been produced here.

Retrace your route to the intersection with S.C. 38. Turn left on S.C. 38 and drive south for 7.1 miles to S.R. 35-18. Turn right, follow S.R. 35-18 to S.R. 35-44, turn left, and head south for 2.4 miles to S.R. 35-31. Follow S.R. 35-31 south for 0.9 mile to S.C. 34, turn right, and drive 3.9 miles to the bridge over the Great Pee Dee River, where you’ll enter Darlington County. Organized in 1798, the county was named either for Darlington, England, or for a Revolutionary War colonel of that name. Historians do not know for sure.

Continue west on S.C. 34 for 2.7 miles to Lowders Hill Cemetery, located on the left. Buried here is Major Robert Lide (1734-1802), who served as an officer under Francis Marion for much of the war. Also interred in the cemetery is Samuel Welds (1751-1802), a private in the Patriot army.

Continue on S.C. 34 for 0.2 mile, where you’ll find two state historical markers for Revolutionary War soldiers. One honors Major Robert Lide, and the other pays tribute to La[e]muel Benton. During the eighteenth century, Benton owned much of the land north of the current tour stop. In the fight for independence, he served as a militia colonel for the Swamp Fox and later as a forager for Major General Nathanael Greene. As the new state and republic struggled to survive, Benton distinguished himself as a statesman in the state legislature (1781-87), at the South Carolina Constitutional Convention (1790), and in the United States House of Representatives (1793-99).

Proceed west on S.C. 34 for 1.1 miles to S.R. 16-29, turn right, and drive north for 1.8 miles to S.R. 16-892. A state historical marker at the junction notes that the grave of Evan Pugh, a noted Patriot minister, is located nearby.

To see his grave, turn right on S.R. 16-892 and proceed 0.5 mile to the cemetery. Born in Pennsylvania to Welsh parents, Pugh (1729–1802) moved to Virginia with his parents as a youngster. There, he studied surveying from George Washington. He subsequently renounced his Quaker beliefs and became a Baptist. In 1762, Pugh took up residence on the banks of the Pee Dee and emerged as one of the leading Baptist ministers in the area. During the Revolutionary War, he was an outspoken advocate of independence.

Retrace your route to S.C. 34, turn right, and proceed west for 7 miles to U.S. 52 Business (Main Street) in Darlington, the county seat. Turn right on Main Street, drive south for 1.7 miles to S.R. 16-179, turn left, and go 1.2 miles to the state historical marker for Samuel Bacot (1745-95).

Bacot settled in the South Carolina back country around 1770. Throughout the Revolutionary War, he served as an officer in the South Carolina militia. Although he was taken prisoner when Charleston fell to the British, he and some companions were able to escape. Thereafter, General Francis Marion benefited from the service of Lieutenant Bacot.

His grave, 0.5 mile northeast, is located on private property.

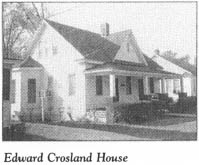

Turn around and proceed 2.6 miles northwest on S.R. 16-179 to S.C. 340. Turn left and drive southwest for 9.3 miles to S.C. 403. Buried here in the cemetery of Lake Swamp Baptist Church is Augustin Wilson, a Revolutionary War soldier. His grave is distinctive because it is marked by a partially embedded cannon.

Born in Virginia, Wilson served with the North Carolina troops in the frontier battle against Tories and Indians in South Carolina. He settled in the Palmetto State in the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

A state historical marker adjacent to the cemetery pays tribute to Wilson.

Turn right on S.C. 403, drive north for 4.5 miles to U.S. 401, turn left, and proceed 8.2 miles southeast to the Lynches River, where Darlington County gives way to Lee County.

Continue on U.S. 401 for 1 mile to S.C. 341. Turn right and drive north for 1.3 miles to the state historical marker near the homesite of Henry Durant, another gallant soldier who served under the Swamp Fox.

Proceed 9 miles on S.C. 341 to the intersection with U.S. 15 and S.C. 34 in downtown Bishopville, the seat of Lee County. A state historical marker near the intersection calls attention to the Battle of Ratcliff’s Bridge, which took place several miles away on the Lynches River on March 7, 1781.

To visit the battle site, turn right on U.S. 15/S.C. 34 and drive 3.7 miles to the bridge over the Lynches River. It was just south of this bridge that General Thomas Sumter was defeated by Loyalists commanded by Major Thomas Fraser.

Sumter had moved to this place after a long and difficult retreat following his aborted attempt to take Fort Watson. During the course of the retreat, Sumter’s paralytic wife and his young son joined him. When Major Fraser surprised the Gamecock here, the Americans suffered ten killed and forty wounded.

Near the bridge, you’ll notice a state historical marker for Captain Peter Du Bose (1755-1846). His grave is located approximately a hundred yards north of the marker in an old family cemetery.

During the Revolution, Du Bose was one of General Marion’s guerrillas. After the war, he lived near the current tour stop, where he operated a river ferry at what was known as Du Bose’s Crossing.

Retrace U.S. 15/S.C. 34 to Bishopville. Turn right on S.C. 34 and proceed west for 10.2 miles to the Kershaw County line. Established in 1798, the county was named for Joseph Kershaw, the Patriot leader who founded nearby Camden.

Continue on S.C. 34 for 9.1 miles to U.S. 1 in historic Camden, the seat of Kershaw County. Turn left on U.S. 1 (De Kalb Street) and drive 1.4 miles west to U.S. 521 (Broad Street) in the heart of the old town. Turn left on South Broad Street and drive five blocks south to the Historic Camden Revolutionary War Site. Visitors to this ninety-eight-acre site are treated to a wonderful walk back into the Revolutionary War era, when Camden was one of the most important places in South Carolina.

In 1970, the Camden Historical Commission and the Camden District Heritage Foundation initiated a joint project to restore the site of the original town. Archaeological research and work led to the reconstruction of old Camden, which was fortified by the British after their decisive victory north of town on August 16, 1780.

Since its inception, this Revolutionary War park has grown in sophistication, in the number of reconstructed buildings and sites available for inspection, and in the number of historical programs offered. Reenactments and living-history programs are presented throughout the year.

A fee is charged for touring the magnificent complex.

The tour begins at the visitor center, which is adjacent to the parking lot. Located in the Cunningham House, which dates to around 1840, the visitor center contains the tour headquarters, a gift shop, and the administrative offices of Historic Camden. The structure was relocated here from its original site at the southeastern corner of Market and De Kalb Streets.

Walk to the second building on the tour. Constructed in 1789, the Craven House was moved here from its original location on Mill Street.

The slide show offered at the third tour stop, Dogtrot, provides an excellent orientation to the early history of Camden.

The oldest inland town in South Carolina, Camden was born from a 1730 order by King George II that created eleven townships on the rivers of the colony. Several years after that, surveyors laid out the town of Fredericksburg in the dank swamps of the Wateree. Early settlers found life miserable, and the early settlement failed to thrive.

In the early 1750s, large numbers of Quakers from Ireland took up residence on the high ground northeast of the original settlement, and a village began to emerge. English-born Joseph Kershaw made his appearance here in 1758 and promptly built a store within the present limits of the town. He called the place Pine Tree Hill. However, in 1768, it was named Camden in honor of Charles Pratt, Lord Camden. Ironically, Pratt later proved one of the most outspoken advocates in Parliament for the rights of the colonies.

A street grid and a town plan were prepared in 1774. The streets of today’s Camden are those that were laid out on the eve of the Revolution.

Growth came quickly for Camden, which had assumed a place of prominence by the time sabers began to rattle. Much of the reason for the town’s early importance was its strategic location. A number of old Indian trading trails, including the Waxhaws Road and the Catawba Path, intersected here. Moreover, the town was a significant port on the Wateree River, thus making it a center for trade and transportation.

During the Revolution, Camden was key to the British plan for subduing South Carolina in the wake of the fall of Charleston. British forces took possession of Camden just three weeks after capturing the port city. Two months later, the British claim to Camden was strengthened by the rout of American forces north of town at the Battle of Camden (covered later in this tour). Following that victory, the British made an intense effort to fortify Camden so it could serve as the principal supply post for all their operations in the South. A palisade was constructed around the town proper. On the perimeter, six strong redoubts provided further protection. Portions of those old fortifications are visible on the tour of the restoration complex.

From June 1, 1780, until the British defeat at the Battle of Hobkirk’s Hill on April 25, 1781, the town was occupied by the Redcoat army.

After enjoying the audiovisual presentation, proceed to the fourth tour stop, the Bradley House. This log house was relocated here from its construction site 9 miles east of Camden. Built around 1800, it is typical of the homes of many of the settlers who came here in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Inside, you will find a variety of exhibits detailing life in Camden up to the early years of the Revolution.

From the Bradley House, proceed to the Drakeford House, a log dwelling constructed around 1812 by Richard Drakeford, a Patriot soldier. In 1970, the house was taken apart log by log, moved here from its original site 12 miles north of Camden, and painstakingly reassembled.

Displayed in the Drakeford House are a number of exhibits related to Camden’s role in the Revolution. Of special interest is a model of the Kershaw-Cornwallis House (visited later on this tour).

Several nineteenth-century buildings of little or no significance to the Revolution are also located at the complex.

Once you have finished touring the buildings, return to the visitor center. You may now either walk or drive to the site’s archaeological findings and reconstructions; because of the distances among the sites, most visitors may wish to use a vehicle.

From the visitor center, follow the road through the complex to the reconstructed town palisade. Many of the archaeological discoveries here were based on a map prepared by Major General Nathanael Greene’s engineer in 1781. The reconstructed portions of the town walls resulted from excavations of a site shown on the map. You are looking at what was the southern wall of the stockade erected by the British in 1780. The fortified Camden covered one city block on each side of Waxhaws Road (now Broad Street).

Follow the road as it winds north to the reconstructed portions of the Northeast Redoubt. This fort stretched across what is now Bull Street. At present, only a third of its earthworks and dry moat have been rebuilt.

Proceed south to the Kershaw-Cornwallis House, by far the most spectacular structure at the complex. This magnificent white frame two-story Georgian mansion is an exact replica of the house that Joseph Kershaw was in the process of completing when the British arrived in the late spring of 1781. Historic Camden officials used drawings to craft this authentic reproduction during the national bicentennial. Archaeological work revealed the original brick foundation, which allowed officials to build the reconstructed mansion at the location of the original.

Upon the arrival of the British, the Kershaw-Cornwallis House became the headquarters of the high command. Cornwallis used the house when he was in town, but for the most part, it was occupied by his immediate subordinate, Lord Francis Rawdon, the twenty-six-year-old Irishman who commanded the British base at Camden.

Born into a family of nobility, Rawdon was described as tall and athletic—and as the ugliest man in all of England. He gained the respect of British officials with his outstanding performance at the Battle of Bunker Hill early in the war. Six years later, though he was heavily outnumbered, Rawdon scored a tactical victory over Nathanael Greene on the northern side of Camden at Hobkirk’s Hill.

After the British base here was abandoned, the Redcoat garrison retreated to Charleston, where Lord Rawdon ultimately assumed command of the eight thousand troops in South Carolina and Georgia while Cornwallis made his futile attempt to conquer North Carolina in early 1781.

During the British occupation of Kershaw’s mansion, the master of the house was forced to seek exile in Bermuda because of his support of the American cause. Upon his return to Camden after the war, Kershaw was pleasantly surprised to find his home in good condition, save for the furnishings. He died in the house in 1791 at the age of sixty-four.

After standing unoccupied for many years, the mansion burned to the ground during the Union occupation of Camden in 1865.

Visitors to the first floor of the reconstructed house are treated to period antiques, paintings, and artifacts from the long history of the mansion.

Adjacent to the Kershaw-Cornwallis House is the reconstructed Second Redoubt. Before this fort was rebuilt, the integrity of the site had been destroyed by its use as a landfill. However, with the aid of General Greene’s map, the complete redoubt has been replicated.

Continue south on the road as it circles to the Powder Magazine. Portions of the foundation of this large building have been reconstructed. When erected by the Americans in 1777, the structure featured forty-eight-inch walls. Joseph Kershaw supervised its construction.

From the magazine site, the road makes its way west to a nature trail. A thirty-minute walk on this scenic trail will take you to a small pond and the bogs that lie beyond it. Joseph Kershaw built mills on this waterway in the years preceding the Revolution.

Return to the parking lot at the visitor center, then exit left from the Historic Camden Revolutionary War Site on to Broad Street. Turn west almost immediately on Meeting Street and proceed one block to the Quaker Cemetery, located near the intersection with Campbell Street.

This majestic, tree-shaded burial ground is one of the most historic in the upstate. Four acres were deeded to the Quakers of Camden in 1759, on which they were to locate their meeting house and cemetery. Since that time, the graveyard has been substantially expanded. It is now owned by the city of Camden.

From colonial times onward, people from all walks of life have been buried here. A leisurely stroll around the walled and terraced plots reveals monuments to men and women from virtually every military campaign in which America has been involved.

Numerous Patriots are interred in this historic ground.

At least two Revolutionary War surgeons, Dr. James Martin and Dr. Isaac Alexander, are buried here. Dr. Alexander participated in the Battle of Camden and ministered to Baron de Kalb, the French officer, as life ebbed from his body on the battlefield.

Another stone marks the grave of Captain Benjamin Carter. It was Captain Carter who located de Kalb’s hastily made grave and removed the remains of the Patriot officer for reinterment in the churchyard at Bethesda Presbyterian (visited later on this tour).

One of the most distinguished Revolutionary War veterans buried in the Quaker Cemetery is Joseph Brevard (1766-1821). Born in Iredell County, North Carolina, Brevard was one of eight brothers who fought on the side of the colonies. One of his older brothers, Captain Alexander Brevard, was a bright star in the otherwise dismal American performance at the Battle of Camden.

Joseph Brevard joined the Continental Army at the age of seventeen near the close of the war. When hostilities ended, he was a lieutenant.

He then settled in Camden, where he became a prosperous and respected attorney and was elected to the bench. As a judge, Brevard was widely recognized as a legal scholar. In 1818, he was elected to the Sixteenth Congress of the United States.

Without question, the Revolutionary War-era grave that attracts the most interest is that of Agnes of Glasgow. A stone wall encloses her grave, which is marked by a single stone and a sign reading, “Here lies the body of Agnes of Glasgow, who departed this life February 12, 1780, age 20.”

Beyond that basic information, fact merges with legend. According to longstanding tradition in Camden, Agnes, last name unknown, was a young Scottish lady of striking beauty. The sad day came when she was forced to bid farewell to her lover, a young lieutenant in the British army, as he boarded a frigate at Glasgow and headed for the war in America.

Days of separation turned into months of sadness and agony. Finally, Agnes could stand it no longer. She made her way to the docks and implored the captain of an American ship to give her passage. He tried to dissuade her from making the long voyage to a foreign land ravaged by bloodshed but finally acceded to her demands.

Upon her arrival at Charleston, Agnes was escorted to British headquarters, where she met a crusty old sergeant who had served under her boyfriend, Lieutenant Angus McPherson. She was informed by the sergeant that Angus had suffered wounds in a recent battle. When Agnes asked him to tell her how to get to Angus, he shook his head in dismay. Angus was in Cornwallis’s camp, located 125 miles inland. Between the two lovers were miles and miles of swamps and wilderness, two warring armies, and Indians. Undaunted, Agnes begged the sergeant to help her. He directed her to an Indian chief who was preparing to make a canoe trip back to his village, which was located not far from the British encampment.

Agnes arrived safely at British headquarters after a long, difficult journey by water. An orderly escorted her to a nearby field hospital, where she found the poor, lifeless body of her Angus lying on a cot. He had expired only a few moments before her arrival.

Heartbroken, Agnes began wailing and threw herself across Angus’s body. At length, hospital attendants walked over to the cot to console her, only to discover that she, too, was dead—of a broken heart.

Moved by the circumstances of her death, a British officer ordered that Agnes be buried in the Quaker Cemetery and that a marker be placed on her grave. It is said that the inscription on her tombstone was made by a soldier’s bayonet.

Historians dispute this romantic story by pointing out that Agnes died three months before the arrival of the British in Camden.

Another version of the story says that Agnes arrived in Charleston just before or after the death of her lover there. Following his death, she is said to have become either a camp follower or the mistress of Cornwallis himself. Legend holds that Cornwallis attended Agnes’s funeral after illness struck her here. He then ordered her burial.

Return to the junction of Meeting and South Broad Streets. Turn left on South Broad. On the left side of the street is the site where the Blue House stood during the Revolutionary War. It was here that Baron de Kalb died from wounds sustained while fighting for the American cause at the Battle of Camden. He was interred with full military honors at the rear of the house. His remains were later transferred to a permanent grave at Bethesda Presbyterian Church.

Drive one block to Bull Street. During the Revolutionary War period, this intersection was the center of Camden, and the four corner lots were dedicated as public squares. When President Washington visited Camden on the afternoon of May 25, 1791, he addressed the public here.

Continue north on Broad across Bull. In the middle of the next block, you’ll see the Kershaw Grave Enclosure on the left. Joseph Kershaw and members of his family are buried here in well-marked graves on land given for an Episcopal church that was never built.

Proceed to the end of the block at King Street. Located on the southwestern corner is the former Kershaw County Courthouse, designed by noted architect Robert Mills in 1825. Under the stairs at the front of the Greek Revival structure is the original tombstone of Baron de Kalb.

On the opposite side of Broad Street is the site of the town’s old jail. During the British occupation of Camden, the jail was fortified as a redoubt. It was here that fourteen-year-old Andrew Jackson was imprisoned by the British.

Continue three and a half blocks north to the Lafayette Cedar, at 1121 Broad Street. This mighty cedar is the only survivor of a double row of cedars planted in 1825 to celebrate the visit of the Marquis de Lafayette to Camden.

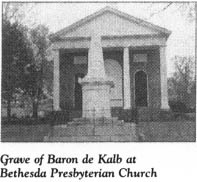

Turn around near the cedar and proceed south on Broad for less than a block to De Kalb Street. Turn left on De Kalb and head east for one block to Little Street. At the northeastern corner stands Bethesda Presbyterian Church. Erected in 1822, this Greek Revival building is another masterpiece by the American genius who designed the Washington Monument, Robert Mills. On the front lawn of the church is another piece of Mills’s handiwork—the monument on the grave of Baron de Kalb.

The man buried here was one of the greatest heroes of the American Revolution. Born to peasants in Huttendorf, Bavaria, in 1721, de Kalb left home as a teenager to join the French army. In time, he attained the rank of major. His marriage to an heiress in 1765 led to his retirement. However, when Louis XVI ascended to the throne in 1774, the retirement ended upon de Kalb’s promotion to brigadier general.

Drawn to the cause of the American colonies, de Kalb crossed the Atlantic with a distinguished friend and fellow officer in the French army, the Marquis de Lafayette, in 1777. After their arrival in Georgetown, the two volunteers made their way to Philadelphia, where they received a less-than-hearty welcome, even though history would prove them to be the two most valuable European soldiers to fight for the American cause. So discouraged was de Kalb that he was preparing to journey back to France when the Continental Congress appointed him a major general in September 1777.

He spent his first winter in America with George Washington in the ordeal at Valley Forge. Then, in the spring of 1780, de Kalb received his first important assignment, albeit a hopeless one. He was dispatched with a strong army of Continental soldiers to the aid of the besieged city of Charleston. By the time his starving troops approached the port city, it had fallen to the British.

Three months later, de Kalb had his greatest—but also his last—day as an American freedom fighter. His gallant stand at the Battle of Camden will be covered later in this tour.

De Kalb was originally buried by British authorities in an obscure grave between two English officers. Dr. Isaac Alexander moved the body from the original grave to one at the Blue House, which he marked with the tombstone now embedded in the old courthouse. On March 8, 1825, de Kalb’s remains were buried for the third and last time. The reinterment service at the present stop was attended by a special guest, the Marquis de Lafayette. An eyewitness described the scene as the French hero paid tribute by laying the cornerstone: “While the stone was slowly descending to close the vault, the General, bending with deep humility and great emotion over it, followed it with his hand to its place, and a funeral dirge increased the awful solemnity of the event.”

The impressive monument stands atop the grave. Its massive base consists of twenty-four blocks representing the states in the union at the time of the dedication. A tall obelisk of white marble surmounts the base. Each side of the obelisk bears an inscription. The southern side reads, “To DeKalb: Here lies the remains of BARON DeKALB, a German by birth, but in principal a citizen of the world.”

Return to Broad Street, turn right, and drive north to the Camden Archives and Museum, located at 1314 Broad. Housed in the old Carnegie Library, this research facility is open to the public. It holds a wealth of historic documents and artifacts related to the history of Camden and Kershaw County.

Just north of the archives building, turn right on Laurens Street. Drive east for four blocks to the Washington House, located just north of the junction with Mill Street at 1413 Mill. This impressive two-story frame house was the site of an elaborate reception and banquet for President George Washington during his visit to Camden. The house was moved here in the early twentieth century from its original location in the heart of town at the corner of King and Fair Streets.

Return to Broad Street, turn right, and drive north for six blocks to the 200 block of Broad, where you’ll see a state historical marker for the Battle of Hobkirk’s Hill. On April 25, 1781, this ridge, now integrated into residential Camden, was the scene of a hard battle between the British, led by Lord Francis Rawdon, and the Americans, led by Major General Nathanael Greene.

After his successful retreat from Lord Charles Cornwallis through North Carolina in February and March 1781, Nathanael Greene turned his attention to South Carolina, intent upon drawing the British from the state. At the top of his list of places to strike was the British base at Camden. Cognizant of the disastrous defeat suffered by his predecessor, Horatio Gates, at Camden the previous summer, Greene was poised to exact a measure of revenge against the enemy.

As Greene’s army marched the tedious 130-mile route to Camden, it passed through an area populated by a significant number of Tories, who kept Rawdon apprised of the Americans’ movements.

Nonetheless, the British commander faced a difficult situation as he awaited Greene. Rawdon had been forced to send Colonel John Watson and almost half the Camden garrison to attempt to destroy Francis Marion’s vexing partisans in the wilderness of the Pee Dee. His problems were compounded when Greene detached the legion of Lighthorse Harry Lee to support the Swamp Fox.

Greene’s starving soldiers made camp 4 miles south of Camden, where they were welcomed by farmers who provided what scant food they had hidden in the nearby swamps. The farmers advised Greene that he would find better supplies on the northern side of town. Meanwhile, Greene received reports detailing the strong fortifications at the British base in Camden. Convinced that his army could not succeed in a direct attack, he decided to take the advice of the farmers and move to the northern side of town. There, he hoped he could entice Rawdon into attacking him. The plan ultimately worked, but its results were not exactly satisfactory.

Greene selected the strong natural position here at Hobkirk’s Hill, which at the time was a ridge 0.5 mile long that rose eighty feet at its highest point. His army set up camp on the elevated site on April 20. While Greene kept a constant eye on Rawdon, he anxiously awaited the arrival of General Thomas Sumter and his army of partisans. But as was so often the case, Sumter was committed to prosecuting the war in his own way. Cooperation from the Gamecock was not forthcoming.

Without reinforcements, Greene’s army stood 1,551 men strong. Almost 80 percent of those troops were skilled Continentals from Maryland, Delaware, and Virginia. Conversely, Rawdon’s depleted garrison could field but 800 men.

On April 22, a report reached the American camp that brought Greene great anxiety. After failing in his mission to catch the ever-illusive Marion, Lieutenant Colonel John Watson was said to be returning to Camden. His force would make the British army larger than the American force. Acting on that report and the news that the Swamp Fox was too far away to help, Greene decided to send the bulk of his army to a camp southeast of Camden, where it could block Watson’s movement toward the town. Soon after moving his troops on April 23, Greene received new intelligence revealing that Watson had given up on the idea of returning to Camden and was on his way to Georgetown. Consequently, he ordered his army back to Hobkirk’s Hill on April 24, and the stage was set for a showdown.

Although his army was only half the size of the American force, Lord Rawdon, always bold, decided to attack Greene.

April 25 broke clear and warm. The American camp was confident. The field guns arrived between nine and ten o’clock that morning, to the lusty cheers of Greene’s soldiers. The troops had by then completed their morning exercises and were relaxing and eating breakfast with their arms stacked.

Suddenly, the sound of musket fire could be heard. Soldiers scurried for their arms as General Greene barked orders to his officers. Rawdon had launched a strike against the Americans with every man he had available—even the British musicians had been ordered to cast their instruments aside and take up muskets. Most of Rawdon’s nine hundred troops were top-quality soldiers equal in skill to Greene’s Continentals.

The American lines formed quickly. In view of his numerical superiority, Greene attempted to flank Rawdon’s army after it was briefly thrown into confusion by the initial blasts from the American artillery. However, the flanking maneuver failed, and Greene watched in dismay as the Redcoats poured around his flanks. Regiment after regiment of Continentals was forced to fall back. To make matters worse, Colonel William Washington and Lieutenant Colonel John Gunby of the First Maryland committed grievous tactical errors in the heat of battle.

Had it not been for a last-minute stand by the First Virginia and some gallant Marylanders—some of whom scrambled to save the artillery and push it to safety—the American defeat would have been a complete rout. As it was, Greene suffered 266 casualties, including 18 killed. Rawdon lost 358 men, 38 of them killed.

Even though he had bested a larger American army and forced its retreat, Rawdon gained nothing more than a Pyrrhic victory at Hobkirk’s Hill. Unlike Greene, who could replace his lost troops, the British commander had no source for additional soldiers. As a result, he soon abandoned the base at Camden and moved back to Charleston.

At it turned out, Nathanael Greene fared just as he had against Cornwallis in North Carolina—he lost the battle but won the war.

Some of the people who live in the fine homes here claim that the ghost of a soldier killed in the fight makes an appearance from time to time. According to legend, a mounted soldier was decapitated by a cannon blast during the battle, after which his frightened steed carried the headless rider through Camden and into the adjacent swamps. Since that time, the soldier’s headless ghost and his skeleton horse have made their way out of the swamps on the darkest and foggiest of nights. They approach the site of the old battlefield cautiously, as if in search of something. The ghost looks in vain for its head until the crow of the cock signals a new day, at which time the apparition vanishes back into the swamp.

From Hobkirk’s Hill, continue north on Broad Street, which gives way to U.S. 521/U.S. 601 outside of town. It is 4 miles to S.R. 28-58, where you’ll see a state historical marker for the Battle of Camden. To visit the site of the battle, turn left on S.R. 28-58 and proceed 2.3 miles to a roadside turnout, the location of several monuments that are the only visible reminders of the horrific defeat suffered by the Americans on August 16, 1780.

One of the monuments provides some of the details of the battle. In the wake of the British capture of Charleston, Lord Charles Cornwallis assumed command of all British forces in the South. Despite directives from the British war office to conduct passive operations in South Carolina, Cornwallis was determined to be aggressive, for he correctly recognized that most of the resistance to the Crown in the colony had been eliminated or stilled. Not a Continental soldier was to be found in all of South Carolina. Only Sumter and Marion and their partisans were of any serious concern to Cornwallis. Thus, he sent Lord Rawdon to fortify Camden as a primary base and lesser officers to establish outposts at Cheraw, Rocky Mount, and Hanging Rock. These bases were necessary to establish a supply line for Cornwallis’s planned invasion of North Carolina.

On July 13, in an attempt to revive the sagging American fortunes in the South, the Continental Congress appointed General Horatio Gates, the hero of the Battle of Saratoga, as commander of the Southern Department. Before he left Virginia en route to South Carolina, Gates was warned by Charles Lee to “take care lest your Northern laurels turn to Southern willows.” In retrospect, Lee’s words are haunting.

Gates rendezvoused with his command in central North Carolina on July 25. There, he found Baron de Kalb and his fourteen hundred soldiers, primarily Continentals from Delaware and Maryland. The men had been en route to aid Charleston when the news of its fall arrived. De Kalb turned his starving army over to Gates.

To the amazement of the destitute troops, their new commander ordered them to be ready to march on a moment’s notice. Gates’s optimism was infectious. According to Colonel Otho Williams, “The … order was a matter of great astonishment to those who knew the real situation of the troops. But all difficulties were removed by the general’s assurances that plentiful supplies of rum and rations were on the route.”

Despite his instant popularity with his new command and the admiration of politicians in the Continental Congress, Gates was not the man for the job, in the eyes of General George Washington. He preferred Nathanael Greene, but Congress did not ask his opinion.

Gates put his army on the move on July 27. Ten days later, the Americans crossed into South Carolina, where they were relieved to find food after the hot, grueling trek through a barren landscape. On August 13, the army set up camp 13 miles north of Camden. Gates’s command had by then swollen to 4,100 men, thanks to the arrival of 1,800 North Carolina militiamen and various other soldiers.

Cornwallis arrived in Camden on the night of August 13. At best, he could field 2,117 men. Most, however, were excellent, seasoned troops. His two wing commanders—Lord Rawdon and Lieutenant Colonel James Webster—were proven leaders. Moreover, the vaunted legion of Banastre Tarleton was on hand. Thus, despite being badly outnumbered, Cornwallis was determined to stand and fight, rather than lose the base at Camden and the 800 sick and wounded soldiers hospitalized there.

Although his command was composed of eight generals, Gates did not bother to confer with them before announcing that the army would make a night march to Saunders Creek, near the present tour stop, and then attack Camden the following morning.

Thus, at ten o’clock on the sweltering, moonless night of August 15, the Americans began marching in the direction of Camden. At almost the exact same time, Cornwallis put his army on the march along a route that was destined to make the armies collide. At about two-thirty on the morning of August 16, that collision occurred. But after fifteen minutes of fighting, there was a sudden, temporary cease-fire.

At a hastily convened council of war, Gates posed a question: “Gentlemen, you know our situation, what are your opinions?”

Silence pervaded the meeting until General Edward Stevens of Virginia spoke up: “Gentlemen, is it not too late now to do any thing but fight?”

Gates concurred with Stevens. After all, the Americans had a better field position and outnumbered the Redcoats by two to one. And Cornwallis was but a mile north of Saunders Creek and had little room to properly deploy his army.

When the fighting resumed, the battle was initially a standoff. Then, suddenly, the Virginia militia fled the field, followed by the North Carolinians. Colonel Williams, the gallant Continental from Maryland, recalled the flight: “He who has never seen the effect of a panic upon a multitude can have but an imperfect idea of such a thing. The best disciplined troops have been enervated and made cowards by it. Armies have been routed by it, even where no enemy appeared to furnish an excuse.”

With the militia gone from the field, Gates knew he had lost his numerical superiority. But unlike the militia, his Continentals stood their ground until the relentless efforts of Rawdon and Webster forced the veteran Americans to give way.

The last gallant stand took place on the right, where de Kalb was in command. In the course of the fighting, which at times was hand to hand, de Kalb had his horse shot from under him. Picking himself up from the ground, the fifty-eight-year-old soldier quickly regained his composure, raised his sword, and exhorted his comrades to rally. As enemy troops closed in, they clapped their hands on their shoulders, in reference to the epaulettes that adorned de Kalb’s uniform, and cried out, “A general, a rebel general!” A British cavalryman made a verbal demand for de Kalb’s sword. Acquiescing, the general extended the sword and asked in French, “Are you an officer, sir?” When the British soldier did not understand the language, de Kalb realized he was not an officer. Willing to surrender only to an officer, de Kalb then made an attempt to escape, but a furious volley took its toll. De Kalb was wounded eleven times before he fell, suffering three bullet wounds, a saber cut to the head, and seven bayonet thrusts to the body. His friend and aide, Le Chevalier de Buysson, used his own body to receive the additional bayonet assaults meant for de Kalb. The mortally wounded general was then raised to his feet and stripped of his hat, coat, and neckcloth.

Blood was pouring from his body when Lord Cornwallis and his entourage appeared. Upon learning that the dying man was de Kalb, the British commander offered these words to his adversary: “I am sorry, sir, to see you; not that you are vanquished, but sorry to see you so badly wounded.”

A small monument stands at the spot where de Kalb fell. He died three days later at Camden, despite the best efforts of British surgeons to save his life.

After de Kalb went down, the battle ended quickly. Gates was nowhere to be found. Having fled the field on the heels of the militia, he turned up in Charlotte on the night of the battle. Three days later, the fifty-four-year-old general was 180 miles away in Hillsborough, North Carolina, where he set up camp.

American losses were staggering. Of the more than 4,000 soldiers Gates put on the field at Camden, only 700 showed up with him in Hillsborough. Upwards of 1,000 Americans died in the battle, though it lasted but a short time. British casualties were extremely light: 68 killed and 256 wounded.

Much of the blame for the terrible loss was placed on Gates. Alexander Hamilton wrote, “Was there ever an instance of a general running away as Gates had done from his whole army? And was there ever so precipitous a flight? One hundred and eighty miles in three days and a half! It does admirable credit to the activity of a man at his time of life. But it disagrees the general and the soldier.”

Despite widespread criticism, Congress exonerated Gates of misconduct. Before the end of the year, however, he was removed as commander of the Southern Department.

As to Cornwallis, he was finally in a position to turn his attention to an invasion of North Carolina.

John Marshall noted this about the Battle of Camden: “Never was a victory more complete or a defeat more total.” Some historians consider it the most disastrous defeat ever inflicted on an American army.

The tour ends here, at the site of the debacle that left the Southern army in shambles and the outlook for the cause of independence bleak. In less than six weeks, however, the fortunes of war would dramatically shift for South Carolina and all her sister states on a rocky landscape called Kings Mountain.