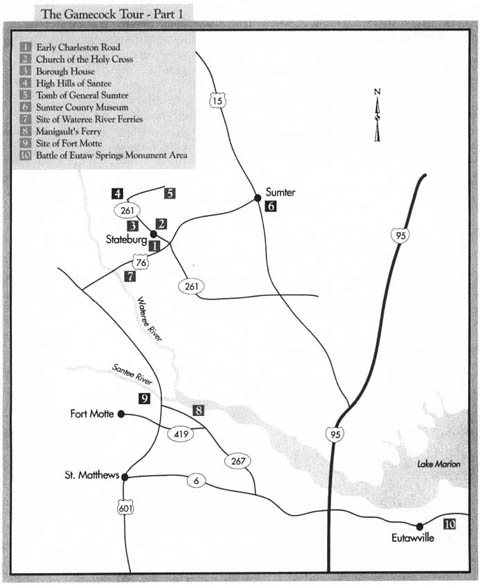

Stateburg, Sumter, St.Matthews, Eutawville, Battle of Eutaw Springs

Total mileage: approximately 154 miles.

THIS TOUR COVERS AN AREA in the heartland of the state. This was the home base of General Thomas Sumter, one of South Carolina’s legendary military leaders during the Revolutionary War. Known as the “Gamecock” because of his tenacity, Sumter emerged from the war as the most controversial of the state’s partisan leaders.

The tour begins in western Sumter County at the junction of U.S. 76/U.S. 378 and S.C. 261. Named for General Sumter, the county was established in 1798.

Drive north on S.C. 261. This route follows a portion of the ancient road that led to Charleston. Originally nothing more than an old Indian path, it became a major artery for both armies during the Revolution. You will pass a roadside state historical marker that recounts the history of the route.

After 0.5 mile, you will be opposite the site of General Sumter’s plantation; Sumter’s home stood approximately 0.75 mile west. Tarleton torched the house while Sumter was away in 1780. Three days later, Lord Rawdon’s troops spread throughout the area. Two local boys, Sam Dinkins and Kit Gayle, made the mistake of shooting at the British soldiers. Despite their youth, Gayle died with a noose around his neck and Dinkins was marched in irons back to a British prison in Charleston.

A mansion appropriately named “The Ruins” was constructed on the plantation after Sumter sold it in 1802.

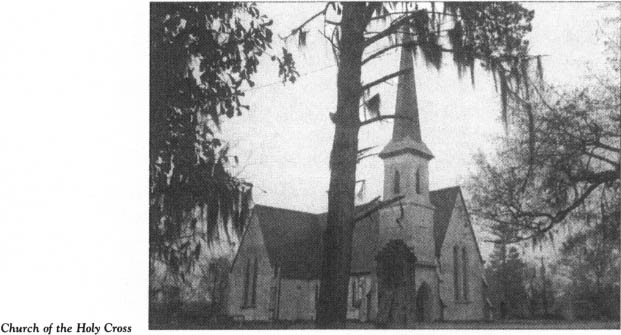

Continue north on S.C. 261 for 0.5 mile to the Church of the Holy Cross, located on the right side of the road in the old village of Stateburg. Erected in the mid-nineteenth century, this handsome Gothic Revival edifice sits on the site of a church that dated to around 1788. The land was donated by General Thomas Sumter. Buried in the adjacent cemetery are a number of Revolutionary War veterans.

A state historical marker for the church and the cemetery is nearby.

Just across the road is the Borough House. Not open to the public, its plantation is said to contain the nation’s largest complex of old buildings constructed of pisé de terre (rammed earth). Of French and Spanish origin, this construction technique involved the packing of sand, loam, and clay into forms.

Erected around 1754, the central portion of the Borough House is of frame construction. Later in the eighteenth century, the estate was acquired by Thomas Hooper, Jr., the brother of William Hooper, one of North Carolina’s three signers of the Declaration of Independence. It was Hooper who added the mansion’s original frame wings. They were subsequently replaced by pisé de terre wings.

During the Revolution, both Nathanael Greene and Charles Cornwallis used the Borough House as their headquarters. In fact, there is a reminder of wartime visitors on the downstairs door. The letters C.A. (for Continental Army) were crudely emblazoned on the door panels by one of Greene’s soldiers using a red-hot poker.

The beautiful estate grounds feature a pre-Revolutionary War garden set amid towering oaks. One of the trees, the Spy Oak, is more than four hundred years old. It received its named after General Greene used it to hang a Tory spy.

The Borough House and Holy Cross Church are the most prominent landmarks in Stateburg, an eighteenth-century village that time has passed by. Long ago, this place boasted homes, stores, an academy, and a library. Settled as early as 1750, it was promoted by Thomas Sumter in 1786 as the site of the future state capital. The name of the village came from that unsuccessful effort.

Continue north on S.C. 261 for 1.9 miles to S.R. 43-488, turn right, and drive 0.3 mile to High Hills Baptist Church.

Organized in 1770, this congregation is the second-oldest of the Baptist faith in South Carolina. One of its charter members was sixteen-year-old Richard Furman. In 1774, Furman was ordained the church’s minister, a post he held throughout the Revolutionary War. Ultimately, he was forced to flee to Virginia with a British price on his head because of his patriotic sympathies. When he returned to South Carolina, he took a leading role in theological education in the new state. Today, Furman University bears his name.

The existing church building, a stately Greek Revival frame structure, was erected in 1803 on land donated by General Thomas Sumter.

You are in an area long known as the High Hills of Santee. It consists of a narrow ridge extending 40 miles along the Wateree River (which is located approximately 6 miles to the west). Nathanael Greene enjoyed the salubrious qualities of the High Hills. During the six-week period between the siege at Ninety Six and the Battle of Eutaw Springs in the summer of 1781, the Continental Army of the South camped in the High Hills. Greene brought his troops back here after fighting at Eutaw Springs on September 8. Three months later, the army moved to a new encampment at Round O.

It was in the High Hills of Santee that Greene received the news of Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown. A joyous celebration took place here at the headquarters of the man whose magnificent retreat through North Carolina had led Cornwallis along the road to ruin.

Follow S.R. 43-488 for 1.4 miles to S.R. 43-400, where a state historical marker notes that a monument to General Thomas Sumter is located nearby.

Turn right on S.R. 43-400. The monument and Sumter’s impressive tomb are located 0.5 mile down the road in a parklike setting.

Born near Charlottesville, Virginia, to Welsh parents in 1734, Sumter received a better education than his partisan counterpart Francis Marion. During the colonial period, he served with Virginia troops in the campaign against the Cherokee Indians.

Upon his return to Virginia from a trip to England, Sumter ran afoul of the law and was imprisoned. He managed to escape and took flight to Eutaw Springs. For the rest of his long life, Sumter would call South Carolina his home.

In the early stages of the Revolution, Sumter played a dual role, serving in the Provincial Congresses and as an officer of South Carolina troops. From 1776 to 1778, he was an intrepid Indian fighter. His military career came to a temporary end in 1778, when he retired to his plantation near Stateburg. However, when Tarleton burned his home, Sumter was spurred to action.

Anxious for revenge, the Gamecock, as he was soon to be called, proceeded to the Patriot stronghold west of the Catawba River, where he began raising militia forces. In 1780, Sumter’s partisan band scored victories at Williamson’s Plantation on July 12 and at Hanging Rock on August 6.

Despite poor showings in the Battle of Fishing Creek and subsequent skirmishes, he was promoted to senior brigadier general of the South Carolina militia on October 6, 1780. Six weeks later, he was badly wounded at the Battle of Blackstock’s. On January 13, 1781, the Continental Congress voted a resolution of thanks to Sumter.

However, over the next eight weeks, he established an unenviable reputation as a commander who possessed poor tactical sense, an unwillingness to prepare, and an inability to cooperate with other commanders.

He mired himself in further controversy by devising a plan that became known as “Sumter’s Law.” To recruit soldiers for his militia, he proposed to pay the new troops with plunder from Loyalists. This scheme did little more than refuel the civil war between Patriots and Tories throughout the state.

By August 1781, when South Carolina officials declared the policy without merit, the Gamecock’s military career was nearing its end. Only weeks earlier, he had been trounced at the Battle of Quinby Bridge even with the assistance of Marion and Lee.

When the South Carolina General Assembly convened at Jacksonboro on January 8, 1782, Thomas Sumter took his seat as a senator. A month later, he resigned his commission as a general.

Despite his shortcomings, a grateful state awarded him a gold medal. Voters showed their appreciation by electing him to additional terms in the state legislature and several terms in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate.

During the last twenty years of his life, Sumter was frustrated by creditors and litigation. When he died at the age of ninety-eight, Sumter was the oldest surviving general of the Revolutionary War.

Although his name was deemed “almost universally odious” by Lighthorse Harry Lee, the Gamecock was endowed with some sterling qualities—boldness, ingenuity, and great bodily strength. Unfortunately, his lack of tactical skills and his other weaknesses tarnished his military reputation and kept him from attaining the legendary status of his fellow partisan, the Swamp Fox.

Also located at the current tour stop is the Chapel of Natalie de Lage Sumter. Buried under this little brick chapel with a red tile roof is Natalie Marie Louise Stephanie Beatrice de Lage de Valude Sumter, the wife of Thomas Sumter, Jr.

Scheduled to attain a high place in the court of France, Natalie fell in love with General Sumter’s son on her return to France from the United States, to which she had fled during the French Revolution. They married in Paris and returned to live here in the High Hills of Santee. Because Natalie was Catholic, General Sumter built this small chapel as a place for her to worship. On occasion, a priest conducted services here.

When she died, the chapel became her sepulcher. Her husband is buried in the surrounding cemetery.

Retrace your route to the junction of S.C. 261 and U.S. 76/U.S. 378, where the tour began. Located nearby is a state historical marker honoring William Tennent (1747-77). A distinguished Presbyterian minister, Tennent was an early advocate of independence. In 1775, he left his church in Charleston and journeyed through the back country with William Drayton on a campaign to encourage support for the colonies. “Thousands heard and believed us… [and] expressed their concern, that they had been misled,” Drayton later recalled.

Tennent did not live to see his dream of an independent America come true. He died of fever several miles south of the current tour stop at the plantation of Captain William Richardson in 1777.

Turn left on U.S. 76/U.S. 378 and drive southeast for 12.3 miles to U.S. 15 in Sumter, the county seat. You’ll quickly note the preponderance of streets with names related to the Revolutionary War. Turn right on U.S. 15 (Lafayette Street), proceed 1.2 miles south to Liberty Street, turn right again, and drive six blocks west to Washington Street. Cross Washington to visit the Sumter County Genealogical and Historical Center, located in the old Carnegie Library building at 219 West Liberty. Open to the public, this facility is a treasure trove of information about the Revolutionary War in the area.

Return to the junction with Washington Street, turn left, and cross Hampton Avenue to reach the Williams-Brice House, at 122 North Washington. The Sumter County Museum is housed in this three-story brick Victorian mansion, which dates to around 1814. Among its holdings are artifacts related to the Revolutionary War.

From the museum, drive south on Washington to Liberty Street, turn left, and return to U.S. 15. Turn right, follow U.S. 15 for 7.3 miles south to S.R. 43-251, turn right again, and drive 1.3 miles to S.R. 43-77. Near this junction stands Bethel Baptist Church. Organized during the Revolution, this church was an offshoot of High Hills Baptist Church. The existing edifice dates to 1849. It is the third building on the site. In the adjoining cemetery are graves of Revolutionary War soldiers. A state historical marker for the church stands nearby.

Continue west on S.R. 43-251 for 2.6 miles to S.C. 120, turn left, and drive 6.8 miles to S.C. 261. Turn right and proceed west for 12.1 miles to S.R. 43-808. Turn right, head west for 2 miles to S.R. 43-51, turn right again, and drive north for 1.2 miles to St. Mark’s Episcopal Church.

The St. Mark’s congregation was organized in 1757 and has been housed in four different buildings since that time. The existing church was constructed in 1853. During the Revolutionary War, St. Mark’s counted many Patriots among its members. The church was located on the major route from Charleston to Camden. British troops burned it before the conflict was over.

A state historical marker for the church is located on the road alongside the building.

The other state historical marker near St. Mark’s commemorates the plantation of General Richard Richardson, one of the elder Patriots in South Carolina. Richardson donated the land on which the church was constructed. His record as a supporter of the colonies in the early days of the Revolution was impressive. As a statesman, he served as a delegate to the First and Second Provincial Congresses. As a soldier, he led troops as a colonel in the Snow Campaign. He also accompanied Drayton and Tennent on their crusade to enlist soldiers to fight for independence. Richardson was then promoted to brigadier general.

Soon after the independent state of South Carolina formed a government, it authorized General Richardson to administer the oath of allegiance to citizens who lived east of the Wateree River. Those who refused to take the oath were banished from the state.

When Charleston fell to the British, General Richardson was captured and imprisoned at Johns Island. When he became ill there, his captors paroled him, fearing he was near death. He made it back to his plantation here, where he died in September 1780 at the age of seventy-six.

Continue north on S.R. 43-51 for 2.2 miles to S.C. 261. Turn left, drive 3.3 miles north to S.R. 43-63, turn left again, and go 2 miles to Poinsett State Park. This is a splendid spot to enjoy Nathanael Greene’s favorite part of South Carolina, the High Hills of Santee, a land of steep hillsides and swamps filled with bald cypress and tupelo gum trees.

Return to S.C. 261, turn left, proceed north for 10.2 miles to U.S. 76/U.S. 378, and turn left again. It is 6.1 miles to the bridge over the Wateree River at the Sumter County-Richland County line. A nearby state historical marker notes that Simmon’s Upper Ferry was located near the bridge. That ferry was used heavily by troops during the Revolution.

Proceed west on U.S. 76/U.S. 378 for 3.5 miles to U.S. 601. Turn left on U.S. 601 and follow it 8.2 miles south to Calhoun County at the Congaree River just north of its confluence with the Wateree River; en route, you will pass through Congaree Swamp National Monument.

This area was the site of a major British line of march during the Revolutionary War. It ran parallel to the Cooper River up to the Santee at its origin near the present stop. Here, the route forked. One prong followed the Wateree to Camden, while the other followed the Congaree to Ninety Six.

Continue south on U.S. 601 for 2 miles to S.C. 267, turn left, and drive 1 mile to the junction with an unnumbered road on the left. Follow the unnumbered road for 2.3 miles north to its terminus at Saw Dust Landing on the Santee River. Near this site was Manigault’s Ferry, where General Thomas Sumter captured an enemy supply train of twenty wagons en route to Fort Motte (covered later on this tour) on February 23, 1781. Sumter maintained a camp on the Santee in this area.

Retrace your route to S.C. 261. Turn right and drive northwest for 1 mile to the junction with U.S. 601/S.R. 9-80. Proceed northwest on S.R. 9-80 for 0.4 mile to S.R. 9-151. In February 1781, this area was the site of a skirmish at Belville Plantation.

Belville Plantation was a stockaded British fortification that encompassed the manor house and outbuildings of Colonel William Thomson. Sumter’s partisans struck here on the morning of February 22. They were greeted by well-directed fire that made it difficult to cross the open field to the fort. Despite the stiff resistance, a contingent of Patriots fought their way to the works and put the torch to some of the buildings. Nevertheless, the British garrison would not capitulate. After thirty minutes of fighting, Sumter called off his warriors.

Turn right on S.R. 9-151 and drive north for 2 miles to the junction with an unimproved road. Turn right on this unimproved road and follow it for 0.5 mile to its terminus near the Congaree River. Located in this swampy terrain was Fort Motte. A granite marker commemorating the heroics here during the Revolution is located somewhere in the surrounding wilderness.

Rebecca Brewton Motte owned the plantation that existed here when the American colonies undertook the struggle for independence. British forces promptly sequestered her mansion for use as their principal supply depot in the back country. As a consequence, Mrs. Motte was forced to take up residence in a servant’s house on her estate.

When Francis Marion and Lighthorse Harry Lee arrived here on May 8, 1781, in the wake of their successful attack on Fort Watson, Fort Motte (as the British called their compound) was being used to store a large supply of gunpowder. It was garrisoned by 150 infantrymen and a small number of dragoons.

Marion and Lee decided to lay siege to the British stronghold. Their troops had just begun digging siege works when news arrived that Lord Rawdon was abandoning the British base at Camden. This sudden development raised concern that Rawdon’s Redcoats might stop by Fort Motte on their march to Charleston. Consequently, the Americans had to act quickly.

Lee devised a plan to use flaming arrows to set fire to shingles on the roof of the Motte mansion. Not only did the matron of the house approve of the plan, but she also provided the means to make it a success. Mrs. Motte delivered to Lee an excellent East Indian bow and a quiver of arrows given to her by her brother, who was a sea captain.

From the siege trenches, an American archer sent two flaming arrows onto the roof. At the same time, Lee trained his artillery on the house to prevent the garrison from knocking the arrows away. Believing they were in imminent danger, the British troops sent up the white flag, and Patriots quickly put out the fire.

Once she was back in control of her house, Mrs. Motte served dinner to both the American and British officers.

Turn around and follow the unimproved road south for 2.5 miles to S.C. 419 in the town of Fort Motte. Turn left and drive 2.5 miles to St. Matthews Episcopal Church.

Established in 1765, the church is now housed in a Gothic-style building erected in 1882. Among the most valued artifacts owned by this historic church is a chalice donated in 1777.

The old church cemetery on the other side of the road contains graves from the Revolutionary War era.

Continue on S.C. 419 to U.S. 601 at Miles Crossroads, where you’ll see a state historical marker for St. Matthews Episcopal Church.

Turn right on U.S. 601 and drive south for 8 miles to the town of St. Matthews. Continue 1.9 miles to U.S. 176, turn left, and drive 3.2 miles southeast to S.R. 9-45. Nearby stands a marker detailing the murder of John Adam Treutlen by a Tory in the waning days of the war.

Treutlen (1726-82), a native of Austria, served as the first governor of the independent state of Georgia. After Savannah fell to the British on December 29, 1778, he took refuge in South Carolina, where he was killed.

Turn left on S.R. 9-45, drive 1.1 miles to S.R. 9-154, turn right, and proceed 0.9 mile to S.R. 9-100. Turn left and head 2.9 miles northeast to S.C. 6. Near this junction stands St. Matthew’s Lutheran Church, organized in the 1760s. A nearby state historical marker pays tribute to the church.

Turn right on S.C. 6 and follow it southeast for 7.5 miles to the Orangeburg County line. Established in 1768, the county was named for William, prince of Orange, the son-in-law of King George II.

Continue for 7.1 miles to 1-95 near the southern shore of Lake Marion, named for the Swamp Fox. It is another 9.2 miles on S.C. 6 to the village of Eutawville.

This community grew up at the place where the last significant battle of the Revolutionary War in South Carolina was fought. Eutaw is a Cherokee word meaning “pine tree.” Following the war, planters from the Low Country began coming here and made the settlement a summer retreat.

Continue on S.C. 6 for 2.7 miles to the Battle of Eutaw Springs Monument Area. Several markers and monuments commemorating the fierce battle are found in this waterside park landscaped with cedars, live oaks, and dogwoods. This small piece of ground, located on the backwater of Lake Marion near the cold-water springs that bubble up from the limestone bottom, is the closest piece of dry land to the site of the famous battle. For years, the waters of Lake Marion have covered the actual battlefield.

After spending much of the temperate summer of 1781 in the High Hills of Santee, Nathanael Greene was of the opinion in early September that his army was large and healthy enough that he could once again go on the offensive against the British in South Carolina. His forces, composed of both Continentals and militiamen, included twenty-two hundred effectives. With him were some of the finest officers of the American army. Indeed, throughout the final years of the war, few generals had such a skilled and gallant officer corps. From Maryland, there was Colonel Otho Williams. From Virginia, there were Lieutenant Colonel Lighthorse Harry Lee, Colonel Richard Campbell, and Lieutenant Colonel William Washington. From North Carolina, there was General Jethro Sumner. And from South Carolina, there were General Francis Marion, Colonel Andrew Pickens, and Colonel Wade Hampton. Thomas Sumter was on sick leave and did not participate.

Anxious to attack the British army under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Stewart, Greene put his men on the march at four o’clock in the morning on September 8. Only 8 miles separated the Americans from the British encampment at Eutaw Springs.

At six o’clock, as the Americans pushed forward, two deserters from Greene’s army alerted Stewart of the impending attack. At that time, the Americans were within 4 miles of the British force, which numbered between eighteen hundred and two thousand soldiers. Stewart believed that his position at Eutaw Springs could be defended and that it offered a way to retreat.

However, when Greene’s army appeared on the very road leading to Stewart’s camp, the British commander grew concerned. In his post-battle report to Cornwallis, he noted, “Notwithstanding every exertion having been made to gain intelligence of the enemy’s situation, they rendered it impossible by way-laying the by-paths and passes through the different swamps.”

On the front line, the Americans positioned the North Carolina militia in the center and the South Carolina militia on the flanks. Behind them was the main line, anchored by Continental brigades from Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina. In the center of the lines were the four American artillery pieces. William Washington’s command made up the reserve.

At nine o’clock, the battle opened with artillery exchanges. Then the American militia pressed forward, quickly pushed aside Stewart’s skirmishers, and charged the British main line. For a while, the militiamen performed like regulars. But when the Redcoats counterattacked with bayonets, the retreat began. It took an advance by Greene’s Continentals to stabilize the line.

Anxious to claim a victory, Greene directed his Virginians and Marylanders to advance with bayonets. When the hard-charging Americans reached the British campsite, the rank and file could not resist the temptation to plunder the enemy tents. Disregarding the pleas of their officers, the Patriots gave up chasing the retreating Redcoats in order to attend to their material needs. In defense of the Americans, it should be noted that the soldiers were in a ragged condition at best. Some of the almost-nude Patriots were using blankets for waistcloths. To keep the leather from cutting into their skin, the emaciated troops had placed moss under their belts and powder-horn straps. British snipers, well positioned in a nearby two-story brick house, began to take a deadly toll on the looters.

For four hours, the two armies were locked in one of the hardest-fought battles of the American Revolution. In the end, Greene, convinced that he could not gain an upper hand, ordered a retreat.

Though both sides claimed victory, neither gained a clear advantage. While the British were able to hold the field, they suffered staggering losses. In fact, they reported a 35 percent casualty rate—the highest percentage by either army during the entire war. Those losses were particularly detrimental to the British cause, for the manpower could not be replaced. Losses on the American side totaled more than 550. Some 17 officers were killed and 43 wounded. And 4 of Greene’s 6 regimental commanders went down; Lieutenant Colonel Campbell was mortally wounded.

In the course of the ferocious fighting, a number of heroes emerged.

No British soldier displayed greater valor than Major John Majoribanks (pronounced “Marchbanks”), whose well-marked grave is located at the current tour stop. When the battle hung in the balance, it was Majoribanks who stepped forward to lead a counterattack against the Patriots looting the British camp. Because of his gallantry, the Redcoats were able to reorganize and ultimately hold their position.

While rallying his soldiers, Majoribanks was wounded. Following the battle, he was transported to Wantoot Plantation, located 25 miles distant. He died there and was buried on October 22, 1781. The plantation is now covered by the waters of Lake Moultrie. Majoribanks’s grave was moved to its present location by the South Carolina Public Service Authority in 1941.

Among the Americans, no soldier displayed greater heroics than Major Denny Porterfield, a young officer from Fayetteville, North Carolina. When Major Porterfield rode into battle on his courser at Eutaw Springs, he presented a splendid picture, adorned with epaulettes and a red-and-buff vest.

At the height of the fight, Nathanael Greene realized he had to send a force to dislodge the British from the brick house on the battlefield. In order to buy time for an attack squadron to be organized, it was necessary to dispatch an American rider within range of the enemy artillery, a mission of immense peril that would most likely result in death.

When Greene called for a volunteer, Denny Porterfield bounded onto his horse and reported to the general. Questioned about his understanding of the danger of the assignment, Porterfield responded that he was prepared to die for the American cause.

At a prearranged signal, the intrepid North Carolinian galloped off toward the enemy. So taken were the British with his heroism that they held their fire until he had passed the range of their guns. However, on his return ride, he was wounded in the chest and fell. His cherished mount continued until it reached its assigned place in the American lines. On hand to witness the return of the riderless horse was Major General Greene. Tears welled up in his eyes.

Following the battle, Greene directed one of Porterfield’s fellow soldiers from Fayetteville to return the fallen officer’s horse to its home. It was on a Sunday afternoon in September 1781 that the soldier rode into the North Carolina town—the first in the United States to be named for the famous Revolutionary War hero from France—with the grim tidings. There, he presented the red-and-buff vest torn by a bullet hole to the bereaved mother.

Major Denny Porterfield was buried on the field where he fell. His grave is now under the waters that cover the battlefield.

Near the park stands yet another state historical marker. It calls attention to Northampton Plantation, the residence of General William Moultrie. It is now covered by the lake that bears his name.

The tour ends here. If you wish to link this tour with the following one, return on S.C. 6 to Eutawville, where you will reach a junction with S.C. 453. Turn left on S.C. 453, proceed south for 7.1 miles to U.S. 176 at Holly Hill, turn right, and head northwest for 15.8 miles to U.S. 301 approximately 15 miles east of Orangeburg.