CHAPTER 10

JONBENÉT’S AUTOPSY

JonBenét on her way to school. Her dog, Jacques, is also in the photo. © John Ramsey.

CHRONOLOGY

December 25 or 26, 1996—JonBenét Ramsey is murdered either Christmas night or early the next morning.1

December 26, 1996—Thursday

1:06 p.m.—JonBenét’s body is found.

December 27, 1996—Friday

8:15 a.m.—JonBenét’s autopsy begins.

2:15 p.m.—JonBenét’s autopsy ends.

7–9 p.m.—A pediatric expert is called in by the coroner for a second opinion on whether there was a recent sexual assault on JonBenét Ramsey’s body.

WHEN SHE LAUGHED, her laughter was full of delight and happiness and sounded like little bells tinkling in a breeze according to her family. The sound reverberated throughout her whole body. Her laughter would cause anyone with her, adult or child, to join in. Those who loved her say JonBenét found complete joy in her world.

FRIDAY, DECEMBER 27, 1996

Her body had been stored overnight in a refrigerated room kept just above freezing. It remained in the original body bags and on the same gurney. The day before, a coroner’s assistant had sealed and numbered the body bags to preserve the chain of custody and ensure the bags wouldn’t be opened before the autopsy. Just minutes now before the autopsy was to begin, the gurney was wheeled into the room.

It was time.

Her autopsy began at 8:15 a.m. on the day after her body had been found. It was performed at Boulder Community Hospital, the same hospital where her mother had struggled to live three years before while recovering each month following out-of-state chemotherapy sessions for Stage IV ovarian cancer.

The Boulder County Coroner, Dr. John Meyer, had been in his position for over nine years, since 1987. He was a board-certified forensic pathologist. Forensic pathologists are trained to look for and determine the cause and manner of death in sudden, unexpected and violent deaths. The autopsy is the primary tool in a pathologist’s investigation.

Dr. Meyer was well regarded by other forensic pathologists. He was elected to four terms as coroner in Boulder County until he was term-limited out of office in 2002.

The autopsy room at Boulder Community Hospital had one stainless steel table. The room was brightly lit, like a surgical theater, and had a rust-colored floor. Several cabinets lined the white walls. Today, the room was crowded with people.

This was the autopsy of a murdered child who had died under mysterious circumstances in a town that hadn’t had a single murder that year. Her body was the most valuable evidence left behind by her killer. Seven people attended the autopsy: two attorneys from the Boulder District Attorney’s Office, two detectives from the Boulder Police Department, Boulder County Coroner Dr. John Meyer and two medical assistants. All wore bluish-green caps and gloves. Dr. Meyer and one of his assistants were fully dressed in surgical gowns, caps, gloves and footwear to prevent contamination. The coroner’s verbal observations during the autopsy would be recorded while the law enforcement officers in attendance used cameras to document every step of the process.

Any murmur of conversation had fallen away when the body bags containing JonBenét’s tiny remains were wheeled into the room. The understanding of what had happened, the murder of a lovely little girl in her own home, surely hit all those in attendance hard. “Brutal” was one way some familiar with the case saw it. “Sadistic,” others thought. The awful reality made for a solemn, sober moment.

The body bags were removed from the gurney and placed with a soft thump on the cold stainless steel autopsy table. The evidence cameras from the detectives and attorneys began to click, flash and whir.

Dr. Meyer cut the seal. The zipper on the first bag grated as it was unzipped, provoking a feeling of dread. The witnesses braced themselves as the second bag was opened and JonBenét’s body was slowly exposed. And they winced almost as one with the horrific realization, again, of why they were there.

Dr. Meyer began speaking into his tape recorder while he examined the outside of her body. JonBenét was still dressed in a long-sleeved white knit collarless shirt with an embroidered silver star decorated with silver sequins. She wore white long underwear with an elastic band containing a red and blue stripe. Her panties were white with printed rose buds. The elastic band proclaimed it “Wednesday.” Wednesday had been Christmas Day, two days earlier. A small red-ink heart had been drawn into the palm of her left hand. It was never determined who drew the heart, although her mother sometimes drew one on her daughter’s hand. Perhaps, her parents later suggested, JonBenét had drawn this one.

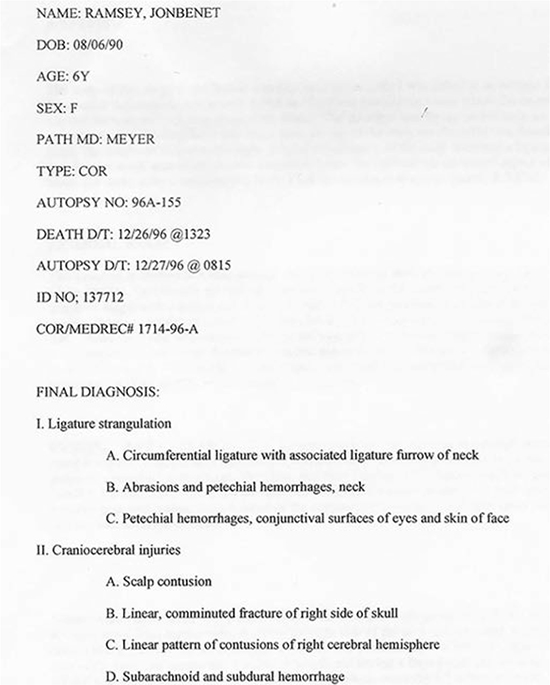

Portion of JonBenét’s autopsy report.

JonBenét’s body was lifted by the shoulders and ankles as the body bag was slid out from underneath her. According to the autopsy report, there was a “rust colored abrasion” on her cheek near her right ear that was clotted with blood. There was also a similar mark on her back. “On the left lateral aspect of the lower back, approximately sixteen and one-quarter inches … are two dried rust colored to slightly purple abrasions.”

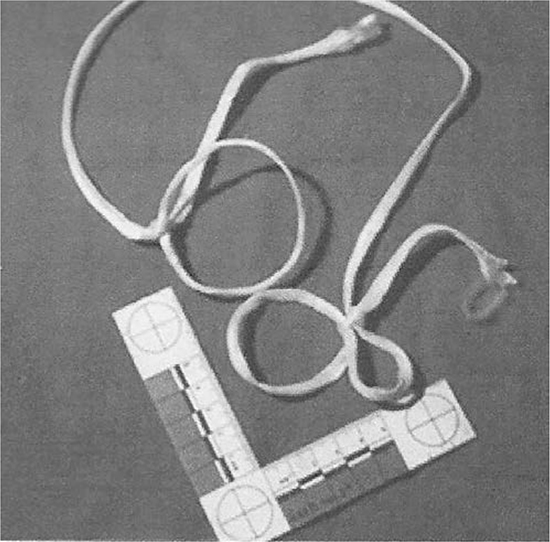

One end of a piece of white rope was wrapped loosely around her right wrist.

Wrist binding found tied on JonBenét. Courtesy Boulder Police and Boulder County District Attorney.

Garrote found embedded around JonBenét’s neck. It was used for strangulation. Courtesy Boulder Police and Boulder County District Attorney.

Her killer had turned another piece of rope into a weapon by using slip knots to create a noose and squeezing the noose closed around her neck. It remained embedded there indicating the force of the strangulation. Dangling from the end of the noose was a wooden handle. Another deep ligature furrow, or rope mark, encircled her entire neck, the coroner observed. The two areas of furrow marks meant the rope may have been squeezed very tightly at least two times around her neck, or the rope and something else had been used to encircle the neck to cause the two marks. The handle on the end of the rope was used to control the amount of pressure on the noose around her neck—a garrote, it’s called. The rope could be tightened until unconsciousness and then loosened on her neck by her attacker at will to bring her back to life. Garrotes are often made of wire and thrown over someone’s head from the back and then tightened through pressure against the front of the neck according to a military officer. This garrote was made from rope. Those who saw it said it was an unusual device that had been carefully crafted. The wooden handle was part of a broken paintbrush from Patsy’s painting supplies, which were kept in the basement. Patsy was an amateur painter. She painted mostly landscapes and flowers. She also painted pictures of roosters and gave them to friends.

During the external exam, the coroner found very small petechial hemorrhages on the inside of both upper eyelids. “There are possible petechial hemorrhages on the right lower eyelids, but rigor mortis on this side of the face makes definite identification difficult,” the coroner’s report would later read. While these hemorrhages can be attributed to more than twenty possible causes, they also can be a sign of a death by asphyxiation.2 The coroner would list asphyxia by strangulation associated with craniocerebral trauma as the two possible causes of JonBenét Ramsey’s death.

Once the coroner cut the cord from JonBenét’s neck, he discovered a necklace, “a gold chain with a single charm in the form of a cross.” JonBenét is pictured wearing this necklace in the Christmas Day photograph on the cover of this book.

Dr. Meyer also noted scratches on JonBenét’s neck that appeared to have been caused by fingernails. Investigators would suggest the little girl had struggled against the tightened noose around her neck. The Ramseys would later say knowing their daughter had struggled to fight her killer as she was being strangled caused them nights and days of agony.

The coroner also clipped JonBenét’s fingernails to look for DNA under them that might belong to her killer. Later tests would find the same foreign DNA in three places: under fingernails from each hand and mixed with blood in her panties.

After thoroughly examining the outside of JonBenét’s body, the coroner began the internal examination while the cameras documenting the evidence continued making their now-familiar sounds.

After opening her scalp area, the coroner discovered a horizontal fracture in her skull that was eight and a half inches long. A small portion of her skull measuring one and three-quarters by one-half of an inch was hit so hard that the blow broke off part of her skull bone along the fracture line. There had been extensive bleeding, but her scalp had not been broken, so the hemorrhage had remained contained within her skull. While there was no external evidence of bruising or swelling of the head, the hemorrhage indicated to Dr. Meyer that the head injury had occurred when JonBenét was still alive.

Police never identified the weapon that likely caused the head fracture, but speculated that it had been a smooth object with no protrusions such as a baseball bat, a flashlight or a board because it had crushed her skull but not broken the skin of her scalp. A baseball bat found just outside the Ramsey home did not belong to the family but could not be traced.

A flashlight similar to one carried by police officers was found on the kitchen counter of the Ramsey home but also could not be traced.

Dr. Meyer found evidence that JonBenét was sexually assaulted, perhaps with an object like the paintbrush handle. Wood fibers found in her vaginal area were later traced to Patsy’s paintbrush handle. A small amount of blood in JonBenét’s vaginal area indicated she was alive during the assault.

Baseball bat found outside the Ramsey home. Courtesy Boulder Police and Boulder County District Attorney

Four possibilities raised by the autopsy report of JonBenét Ramsey would be debated at length among members of law enforcement, the media and the public:

ONE: Whether a stun gun had been used to incapacitate and control JonBenét. In the autopsy report, the coroner noted two abrasions on her lower left back. These, along with similar abrasions on her right cheek, were spaced the exact same measurements apart.

The abrasions became a major controversy when, several months after the murder, Detective Lou Smit, who’d been hired onto the case by the Boulder District Attorney’s Office, theorized that the marks had been caused by a stun gun.

Smit also took autopsy photographs to a forensic pathologist in the greater Denver metropolitan area and asked him to examine them. Dr. Michael Dobersen, a coroner/medical examiner for Arapahoe County, a southern suburb of Denver, is a soft-spoken man who is described by others as thoughtful and meticulous and is highly regarded by his peers.

In the summer of 1994, Dobersen had conducted several stun gun tests on anesthetized pigs to determine the kind and size of markings stun guns would make. He chose pigs because their skin composition is most similar to humans.

Because of his research and testing, Dobersen had been called as an expert witness in multiple cases thought to have involved stun guns. One involved the murder of multi-millionaire Robert Theodore Ammon, an investor killed in 2001 in Suffolk County, New York. At the time, Ammon was involved in a divorce from his second wife. Prosecutors stated the killer used a stun gun to incapacitate Ammon while beating him to death. Dr. Dobersen testified in that trial that a stun gun had been used twice on Ammon’s neck and perhaps twice on his back. Ammon’s second wife’s new husband was eventually convicted in 2004 of the murder.

With regard to the Ramsey murder, Dr. Dobersen said it was very probable that the abrasion marks found on JonBenét had been caused by a stun gun.

After his office had “looked at the possibility extensively,” Boulder Coroner Dr. John Meyer said, “I would not rule out one or the other with regard to a stun gun being used.”

The stun gun theory was controversial because it contributed to the “intruder” theory in the Ramsey murder case since a stun gun would only need to be used if it was necessary to control a victim. Presumably the Ramseys would not have needed to use a stun gun to control their own child. The parents said they’d never owned or used a stun gun. And no stun gun that might have been used by JonBenét’s killer was ever recovered.

Definitive information on a stun gun being used on the little girl could have been determined if her body had been exhumed and her skin examined for burn marks from a stun gun. By the time the stun gun theory came to light several months after the murder, however, Dr. Dobersen stated that it was too late to do this since JonBenét’s skin would have deteriorated too much for an accurate determination to be made.

According to a police report, an officer from the Colorado Bureau of Investigation supported the possibility that a stun gun had been used on the child. “Sue Ketchum of the CBI [Colorado Bureau of Investigation] is shown the photos of the marks and she indicated that they could very well be made from a stun gun.” (BPD Report #26-58.)

Other possible weapons that might have caused the abrasions included protrusions from the bottom of JonBenét’s brother’s toy train track, which was kept in the basement not far from where JonBenét’s body was found. According to an investigator in the Boulder District Attorney’s Office in charge of the Ramsey murder case in the mid-2000s, the protrusions reportedly matched the abrasions exactly. The district attorney at the time, Mary Lacy and other attorneys from her office listened to the investigator’s presentation, but she said, “we discounted the information.”

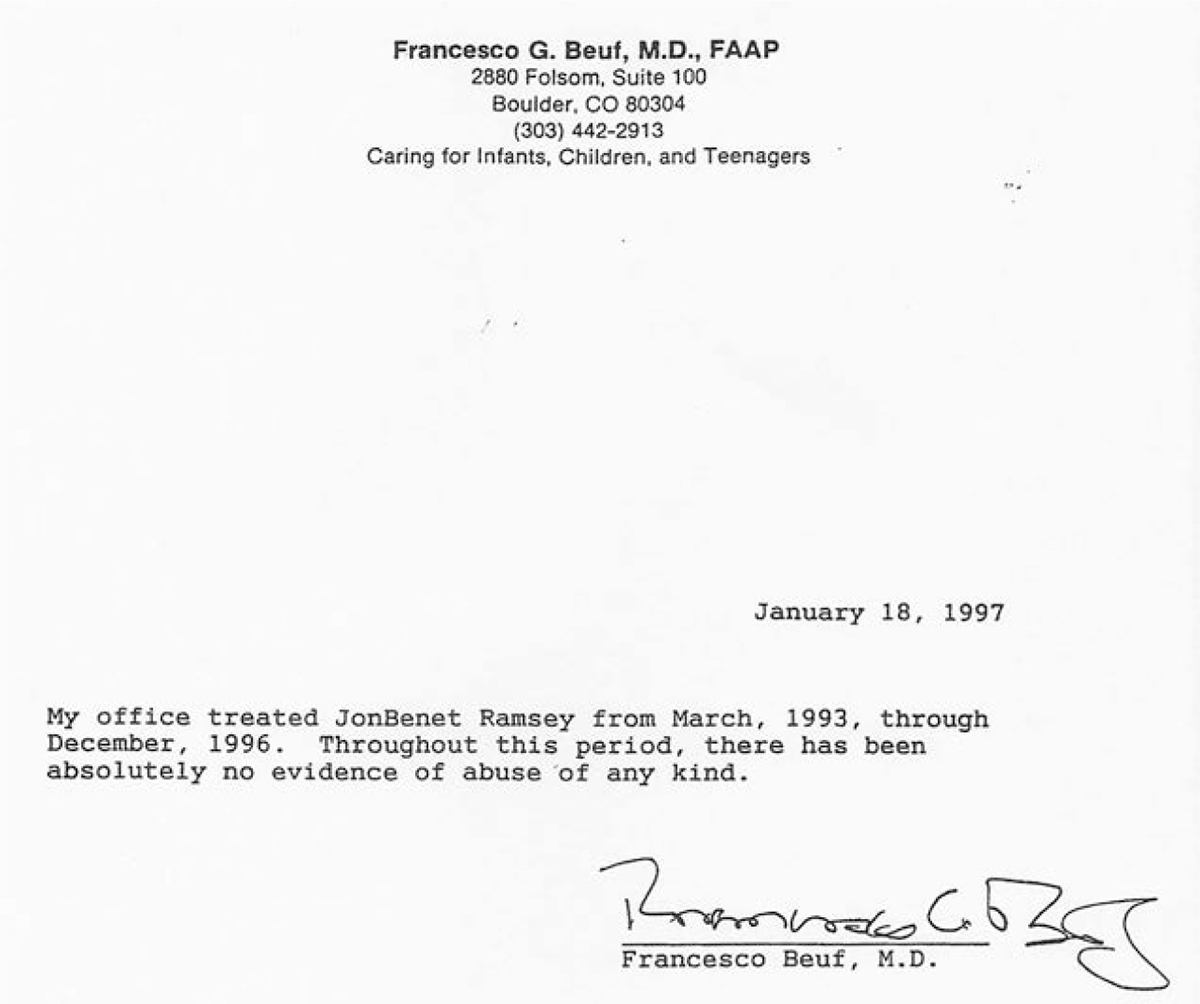

TWO: Whether JonBenét was sexually abused before her murder. The autopsy found “chronic inflammation” in JonBenét’s vaginal wall. At least two detectives on the Ramsey police investigation speculated in media leaks that this condition had been caused by ongoing sexual abuse. Two highly reputable metro-Denver coroners, Dr. John Meyer (who performed the autopsy) and Dr. Michael Dobersen (noted above), both stated that the inflammation could have had several other causes, including improper wiping after going to the bathroom. JonBenét’s pediatrician said she was not sexually abused. And physicians from the Kempe Center, a child abuse prevention organization in Denver, stated publicly after studying the evidence that JonBenét had not been subjected to long-term sexual abuse.

However, considerable speculation continued on this front, especially when the public learned of JonBenét’s many contacts with family doctors including her pediatrician, Dr. Francesco Beuf of Boulder, and questioned whether this signaled a history of trouble at home. JonBenét and her mother had made more than thirty such contacts via either visits or phone calls with Dr. Beuf and with doctors in Michigan near the Ramseys’ summer home over a three-year period from March 1993 to December 1996. (BPD Report #14-1.) After JonBenét’s murder, information related to this number of contacts with these doctors was leaked to media, despite medical records indicating most of the calls and visits had been for coughs, fever, colds and flu-like symptoms.

JonBenét’s medical records show her mother either called or had her daughter visit a doctor several times due to chronic sinus problems and allergic rhinitis as well as irritation and inflammation of portions of the nose. There were also four references in the medical records to accidental injuries: “cheek hit by golf club,” “fell on nose,” “fell and bumped forehead on stairs,” and “fell and bent nail back.” Five references in the medical file were about JonBenét’s vaginal area. One was about a phone report from her mother related to a possible bladder infection, another was about how to treat chicken pox in her vaginal area, another (which was filed under vaginal in medical notes) was about diarrhea. Medical records also show JonBenét received two well-child checks by her pediatrician that included examinations of her vaginal area, and both results were “clear.”

Dr. Francisco Beuf, JonBenét’s pediatrician, and his letter to Boulder police stating no prior sexual abuse.

In a statement to Boulder police, Dr. Beuf wrote: “My office treated JonBenét Ramsey from March 1993 until her death. Throughout this period, there has been absolutely no evidence of abuse of any kind.” (Dr. Francisco Beuf, January 18, 1997.)

Dr. Beuf told two Boulder Police Department detectives the same information in an interview the first week of January 1997. He gave similar information to KUSA TV, when I interviewed him on videotape for broadcast in February 1997:

WOODWARD: When you talked with the police, did they ask you about sexual abuse of JonBenét?

BEUF: Yes, of course they did.

WOODWARD: What did you tell them?

BEUF: I told them absolutely, categorically, no. There was absolutely no evidence, either physical or historical.

WOODWARD: And that’s from seeing her thirty times in three years?3 BEUF: About that—

WOODWARD: What else did they ask you?

BEUF: Well, they asked me mainly the same questions you’ve been asking.

WOODWARD: Relationships with her parents?

BEUF: Relationships with her parents and what sort of child she was. If there was any indication of depression or of sadness. WOODWARD: And your answers?

BEUF: Only that it was appropriate that she was sick and wasn’t feeling too well. The mother was off getting treated for her cancer. She was sad at that.

WOODWARD: Was she an ordinary kid?

BEUF: I think she was extraordinary in the amount of charm she had and the sweetness, I guess, was the quality I appreciated the most. How she was doing things with her friends here, going to Michigan with her parents. Just the fun things in life, and beauty pageants just didn’t seem to be at the top of the heap by any means. WOODWARD: Tell me what she said to you.

BEUF: To be honest with you, I can’t remember. I just remember it made me feel good to see that much happiness and niceness in one spot.

Dr. Beuf would have been required by Colorado law to report any signs of sexual abuse to authorities. In May 1963, a Colorado statute was passed regarding mandatory reporting by physicians about physical injuries of children. The statute was amended to include expanded reporting powers and, by 1969, included mandatory reporting required by a variety of people for suspected physical and sexual abuse of children.

Patsy Ramsey talked with me about her daughter’s frequent visits to the pediatrician: “I was an overprotective mother when it came to my children’s medical needs,” she said in early 2000. “It’s because I had cancer and the fears that go with it, so every symptom with them became something that I needed to have checked out and verified in order to be sure they were okay.”

Patsy also said her cancer doctors told her she needed to keep her children as healthy as possible to protect her own immune system, which had grown weak from her struggles with ovarian cancer.

THREE: Whether JonBenét had wet her bed. The autopsy stated: “The long underwear was stained with urine.” Detective Lou Smit said while fibers from JonBenét’s night clothing had been found on her bed sheets—indicating that those particular sheets hadn’t been changed during the night—no urine was found on them. Other sheets were found in the dryer next to JonBenét’s room, and the Ramseys’ housekeeper said she “believed she last changed JonBenét’s sheets that Monday before Christmas.” (BPD Report # 1-461.) That would have left the options of Monday, Tuesday or Wednesday for the sheets to be changed.

The Ramseys, their attorneys, and some law enforcement officials have stated that JonBenét probably urinated from the brute force of being stun-gunned, strangled or struck in the head, or upon her death. At least one Boulder police narcotics detective, Steve Thomas, however, became convinced very early in the investigation that Patsy had hit her daughter in a rage after JonBenét wet her own bed, then staged the elaborate cover-up with or without John.

Patsy said JonBenét had regressed in her potty training and using the bottle when Patsy was away for her first long period of cancer treatments, but JonBenét had only been three years old when her mother’s treatments began. With regard to anyone in the Boulder Police Department coming to the conclusion that she had killed her daughter because of bedwetting, Patsy would later say, “They just really didn’t get it. JonBenét’s bedwetting wasn’t a big deal to me, but it was to her. I felt badly for her because she would get embarrassed, so I always made sure not to make an issue of it for her sake. The bedwetting was because of my cancer and being gone so much for treatments.” More recently, John said, “Bedwetting really wasn’t an issue. It just wasn’t.”

The fact is that by December 1996, JonBenét was no longer a chronic bed wetter, according to her mother and her father, though Patsy kept a plastic sheet over JonBenét’s mattress and kept overnight diapers handy. A housekeeper in Charlevoix, Michigan, where the family had their summer home, said in a police interview that JonBenét only had “occasional accidents.” Still, some officers used the occasional bedwetting problem to advance their theory that JonBenét was deeply troubled and sexually abused.

According to a website article on Children’s Hospital Colorado, “Doctors don’t know for sure what causes bedwetting or why it stops. But it is often a natural part of development, and kids usually grow out of it. Most of the time, bedwetting is not a sign of any deeper medical or emotional issues.”4

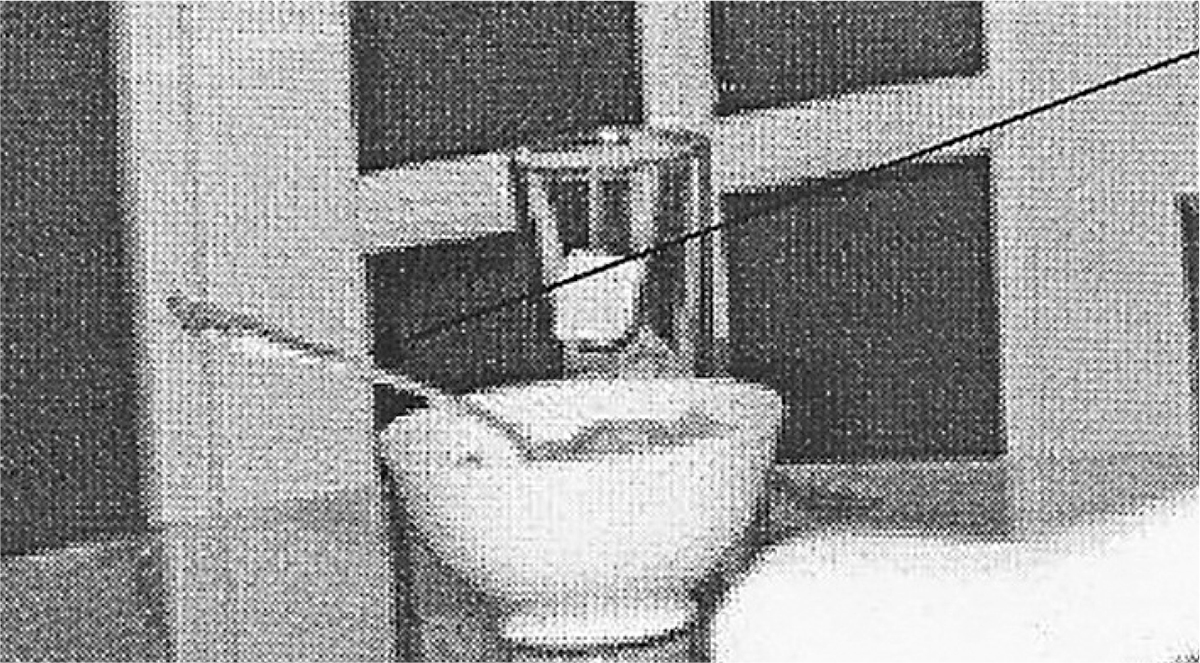

FOUR: Whether material in JonBenét’s stomach indicated a timeline of when she was killed and who killed her. According to the coroner’s observation written into his autopsy report, JonBenét’s stomach contained “fragmented pieces of yellow to light green-tan vegetable or fruit material which may represent fragments of pineapple.” Actual laboratory testing had not been completed at the time the coroner’s report was written.

This statement, however, was enough to add to the speculation that Patsy Ramsey was guilty of murdering her daughter. The morning of JonBenét’s disappearance, a bowl that included chunks of pineapple was photographed by Boulder Police Department investigators on the kitchen table in the Ramsey home. Later tests would reveal both Burke’s and Patsy’s fingerprints on the outside of the bowl.

For more than ten months following the murder, it was assumed and accepted by law enforcement officers and members of the public that, prior to her murder, JonBenét had eaten pineapple that came from inside the home from the bowl in the kitchen. This theory was first floated to the media as a leak, and it became a huge topic of discussion and publicity when the presence of pineapple fragments in JonBenét’s stomach was assumed to be confirmed from the published autopsy report observation. Somehow public opinion tied these “facts” to the belief that Patsy and John Ramsey had killed their daughter.

Bowl of pineapple on kitchen table in Ramsey home. Courtesy Boulder Police and Boulder County District Attorney

The exact material in JonBenét’s stomach and intestines was first discussed with experts at the University of Colorado on October 15, 1997 (BPD Report # 1-1156), more than ten months after JonBenét was killed. Their reports about the contents of her stomach/proximal area were given to the Boulder Police Department more than a year later in January of 1998, (BPD Report #1-1349) one year after JonBenét’s death. And that’s when the mystery deepened and the misconception about what JonBenét actually ate was discovered.

According to previously unreleased BPD reports, laboratory testing revealed that JonBenét also ate cherries and grapes as well as pineapple. Remnants of cherries were found in the stomach/proximal area of her small intestine. “Another item besides pineapple was cherries.” (BPD Report #1-1348.) In that same report: “Another item besides pineapple was grapes.” (BPD Report #1-1348.) Another report expands on the grapes, saying “grapes including skin and pulp.” (BPD Report #1-349.) The food described resembles what is included in most cans of fruit cocktail.

The new information wasn’t released publicly, and the pineapple-only myth with its handy bowl of fruit on the kitchen table of the Ramsey home continued to be circulated. Why does this matter?

• The Boulder Police Department and the Boulder District Attorney’s Office had been operating on an assumption for a year. Who knows where the correct information could have led?

• Among the reasons for checking food content in the body as soon as possible are the possible suggestions related to a timeline of death or perhaps poisoning that it could provide.

Related to establishing a timeline of death, consulted experts disagreed about when JonBenét could have eaten the fruit and how long it would have taken to digest. Her parents said JonBenét was already asleep in the car when they arrived home the evening before she died, and they took her in the house and put her to bed without her waking up. The friends who hosted the dinner party the Ramseys had attended that evening said JonBenét ate no fruit at their home. So, when and where did JonBenét eat it?

Some forensic experts state that digestion time can vary highly from 30 minutes to a few hours to several hours. If JonBenét had eaten some of the food in the afternoon of Christmas Day, which she might well have done without her parents being aware, the longer transit time for digestion would support John and Patsy’s statement that they put their daughter right to bed after arriving home that night. But if forensic experts who contend there is a much shorter digestion period are correct, then it would seem JonBenét’s parents were lying about her being asleep when she arrived home.

Other theories suggested by those familiar with the case state that JonBenét could have been fed later that night by her “Secret Santa” (a person she told a friend’s mother was going to make a secret visit to her after Christmas) or forced to swallow the fruit by a stranger.

According to Dr. Michael Dobersen, the forensic coroner from Arapahoe County south of Denver, assumptions should be avoided and only the facts from an autopsy and summarized police reports considered. “She ate part of the fruit about an hour before she was assaulted and killed,” he has stated. “There are no existing facts on who gave it to her. The assault on her would have stopped her stomach digestion. The digestion also would have stopped when she died.”

JonBenét’s autopsy took six hours. It was finished in the early afternoon, when her body was prepared for shipment to Atlanta for her funeral.

Early that evening, Coroner Meyer stated that he had sought an outside, second opinion on the nature of his vaginal findings. Dr. Andrew Sirotnak, then an assistant professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital, who also worked at Denver’s Kempe Center, consulted with Meyer at the morgue. (BPD Report #7-15 Source.) He agreed with Dr. Meyer that there had been a recent genital injury.

Since the coroner formally released JonBenét’s body to her family in late December 1996, he has rarely spoken publicly about his personal perspective on her autopsy.

“There are so many aspects of it,” Dr. Meyer said. “The things I look at now that bother me the most are [that] this was a tragic death of a beautiful little girl, and my concern is that we’ll never know what happened. That’s the bottom line. My biggest concern is that we won’t find out who killed her.”

The autopsy provided another insight into the killer. Law enforcement officials had learned from it that they were dealing with a person who was either enraged, brutal and cruel or ruthlessly detached and heartless. How else could they explain this murder of a child, especially with the overbearing and torturous violence involved?

“If it doesn’t strike you personally in some way, then it’s time to get out of the business,” Dr. Meyer said. “That having been said, you can’t let that interfere. You do what your job requires and focus on that exclusively. That’s your responsibility to the deceased. Philosophical thoughts are for another time.”

The Boulder Coroner’s Report concluded, “Cause of death of this six-year-old female is asphyxia by strangulation associated with craniocerebral trauma.” Dr. Meyer did not indicate in what order the injuries happened, and another forensic coroner consulted said it would be difficult to determine injury order in this case.5

JonBenét Ramsey was sexually abused, strangled, suffered a horrific blow to the head … and fought back.