CHAPTER 15

CHILD BEAUTY PAGEANTS

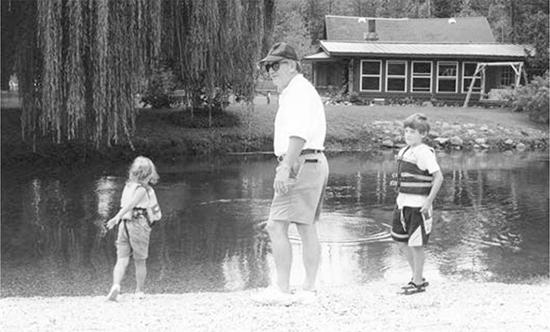

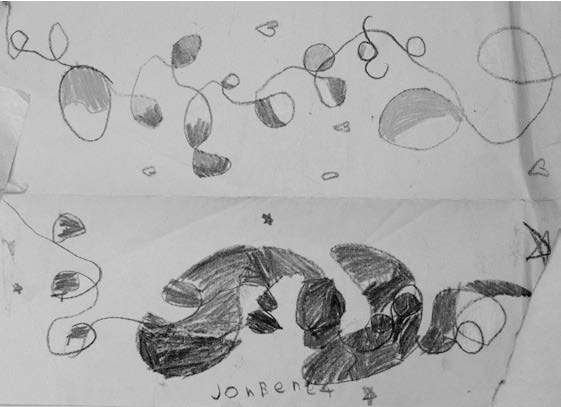

The contrast between JonBenét, the pageant contestant and JonBenét, the little girl throwing rocks into the lake. © John Ramsey

CHILD BEAUTY PAGEANT PHOTOS AND VIDEO became the criminal record the Ramseys didn’t have.

Initial shock at the murder of a child was quickly overridden with broadcasts of the pageants of the dead girl. According to then-Adams County District Attorney Bob Grant, who was asked in 1997 by Colorado Governor Roy Romer to become involved in the Ramsey murder investigation, “Those tapes caught fire and people rose to that publicity bait like hungry jackals. Those in the case and on the periphery. Anyone who was seeking a moment of media spotlight or wanted to be a hero. It was a call of ‘all aboard’ and there was a scramble to see who could be the most important. The investigation was competing with that.”

Five days after JonBenét’s body was discovered, her child pageant videos and still photographs were shown nationally by NBC and CBS on their evening newscasts. Two days later and a week after her body had been found, the videos and photos were broadcast again on January 2 by NBC and CBS. ABC began using JonBenét’s child pageant videos on January 3 and CNN on January 5. From then on, all four national newscasts used the pageant videos and photos of JonBenét in some format nearly continuously for weeks. Local television stations throughout the country got the JonBenét pageant videos and photos from their national affiliates. Photographers who had originally recorded the videos and shot the photos sold them to the media. The Ramsey family did not own any of these rights, nor provide any of the videos or photos.

“Pageants were put on trial,” Betsi Grabe, PhD, a professor of Mass Communications at Indiana University-Bloomington, who studies the effects of news images on public opinion, has said. “If pageants were evil, then who is putting these children into them? The parents. That made them bad parents. The Ramseys were made into ‘look what they made their child do.’ Then you can make the next step in their guilt. It’s a very slippery slope, especially when the video of JonBenét is playing over and over and over on television.”

The underlying apprehension and, in some cases, rage that others possessed regarding John—and especially Patsy—Ramsey were soon on full display. In private conversations and very public radio talk shows, the public demanded to know why a parent would subject their child to the demands of the beauty pageant circuit. “Isn’t there enough pressure in children’s lives already?” people asked. “What kind of lesson does a child learn when they earn success based on how they look?”

The answers did not give a caring portrait of the Ramseys as parents. According to NewsLibrary.com, more than 125 negative articles were written and published throughout the country on child beauty pageants in January and February 1997. At least twice that number referred to JonBenét Ramsey as the “murdered child beauty queen.” The Kansas City Star ran an editorial on January 19, 1997, about John and Patsy entitled “Pillars of a community? These parents are creeps.”

According to Hilary Levey Friedman, PhD, a Harvard sociologist who has studied child beauty pageants as well as JonBenét Ramsey’s involvement in pageants, “This combination of wealth, attractiveness, the mystery of the murder and then the child beauty pageant angle made [the Ramsey murder investigation] a national and international story. The child pageants weren’t something that people were very aware of until JonBenét’s murder. Their reactions to what they saw on television were that the child pageants were extreme and crazy.”

Patsy had represented West Virginia in the Miss America Pageant, entering the pageant when she was in college and winning an award on the national level for dramatic interpretation. She had been in pageants growing up, and her mother had been a big part of this experience with her. “It was fun and we got very close to each other,” Patsy would later say.

JonBenét was first exposed to pageants in 1993 when Patsy was invited to host a Miss West Virginia Pageant and brought her family with her. Patsy also performed a song at the event. It was after this pageant that JonBenét told Patsy she wanted to dress up and dance and perform “like you do, Mom.”

Jeff Ramsey, John’s brother, remembers a family talk during which Patsy asked others about whether JonBenét should be allowed to be in pageants at so young an age. Patsy had started in pageants when she was older than her daughter, who was three at the time. Patsy was reluctant about it, Jeff said, but they all agreed it would be fine for JonBenét to enroll in singing and dancing lessons. What started as singing and dancing lessons soon evolved into pageants.

“Once she made up her mind to do something, she was very committed,” Patsy later explained. “I can assure you if Johnnie-Bee didn’t want to do something, she simply wouldn’t. The pageants were another bonding experience for us.” At home, JonBenét and her girlfriends would play a game of presenting each other to an imaginary audience and pretending to walk across a stage. JonBenét would also do other activities with these same friends, like playing dolls or going sledding.

In the book she and John wrote, Patsy said, “In two years, JonBenét participated in nine pageants. Only two of these were national pageants, an earlier Royale Miss and the Sunburst.” JonBenét primarily competed locally in Colorado and Georgia.1

In June 1995, a few months short of her fifth birthday, JonBenét was voted “Little Miss Charlevoix” in a contest that welcomed girls of all ages. Her competition had been two other girls her age. JonBenét rode in parades that same summer as “Little Miss Charlevoix.” In October 1995, when she was five years old, she won “Little Miss Colorado,” which resulted in her riding in the Boulder Christmas Parade that year. In the first months of 1996, JonBenét competed in a contest at a local Colorado mall, but didn’t place.

According to available records, JonBenét’s participation in pageants increased in 1996. In April, she was in the Colorado All-Stars Kids State Pageant, which awarded all participants a prize. JonBenét won for Cover Girl.

In July 1996, JonBenét was in the Gingerbread Productions of America and won a division title as “Mini Supreme Little Miss.” Also that summer, she won an award in the national America’s Royale Tiny Miss competition and competed in the Sunburst Beauty Contest in Atlanta. She then competed at the national level in the same contest in Atlanta. JonBenét was in a beauty pageant in early November in Denver, and in Georgia’s Dream Star Pageant over the Thanksgiving break.

The many trophies that had been on display outside JonBenét’s bedroom at the time of her death suggest she had won or placed in several pageants. On December 22, 1996, JonBenét also participated in a performance with other children in the Denver metropolitan area as part of AmeriKids, a local non-profit focused on children.

“A couple of times Patsy didn’t want to go to a pageant,” John would later say, “but JonBenét was so excited they decided that yes, they would.” Patsy said in private conversations that child beauty pageants were mostly a Southern activity. “The girls who competed and were serious about it usually did so every weekend,” she added.

John and Patsy Ramsey were deeply affected by how the media portrayed their daughter after she was murdered. As John put it: “A huge amount of the public knew her and formed opinions of her after she was killed because the only pictures and video they saw were those sold by the photographers who had videotaped them at the pageants so they owned the rights to them. We had no say in what was published. We were stunned that we had no rights to the video or the still pictures we hadn’t taken ourselves, but it was something that never occurred to us until then.”

“It was a part of her life that became her identity because it was what the media focused on—the murdered child beauty queen,” said Patsy. “Can you imagine what it was like to have her killed and then her image and who she was reshaped and taken from us, too? In reality, she was our darling girl, and a normal everyday busy child who happened to be in pageants and a lot of other activities because we all enjoyed them.”

According to Dr. Friedman, there is “a range of child beauty pageants.” She puts them into four types with the following descriptions:

Natural beauty pageants: “No makeup is allowed. These pageants are not as prevalent as they once were.”

Hobby Glitz beauty pageants: “They’re local. The children have their hair made up and use makeup. JonBenét participated in these pageants.”

National beauty pageants: “JonBenét participated in these pageants. Qualification is necessary. Hair is professionally made up and makeup is used.”

High-Glitz pageants: “These are the ones you see on television with the current focus on the 2012 television show Toddlers and Tiaras. They wear makeup, including false eyelashes, hair falls, and fake embellishments. There is more award money in these pageants, and it is definitely part of the pageant circuit. Some parents have pageant businesses they’ve developed on their own. This supports the pageant habit.” Dr. Friedman added, “Based on what I have seen and read, JonBenét did not do High-Glitz pageants.”

“Child pageants are predominantly [held] in the South,” Dr. Friedman said. “JonBenét’s murder had a huge impact in the decline of them. But in 2000 they came back and increased in popularity, because parents wanted their children to be involved in them.”

In January 1997, three weeks after JonBenét’s murder, Newsweek magazine published an article with a sentence that launched the dyed-blonde-hair myth about JonBenét and her pageants:

“Patsy Ramsey regularly had her kindergartner’s hair lightened at a beauty salon.”

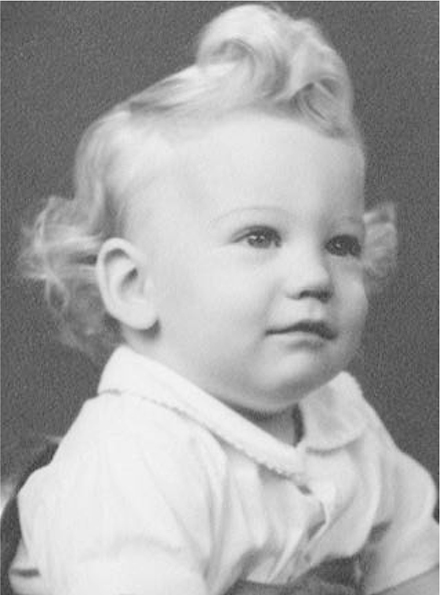

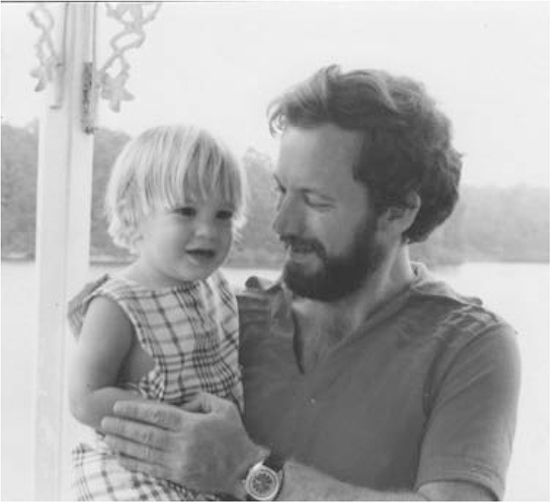

No attribution or beauty salon name was given, and none was needed for this to be instantly accepted as a true fact. The story that JonBenét’s hair was chemically altered to blonde for beauty pageants spread and is still considered accurate. And yet that wasn’t true, according to Patsy, her father, her sister Pam, and JonBenét’s half-sister, Melinda. The blonde hair color came naturally from the Ramsey side of the family. John and his son, John Andrew, both had curly white-blonde hair until they reached eight or nine years of age.

John Ramsey with white-blonde hair as a baby. © John Ramsey.

John Ramsey holds his son John Andrew. John Andrew has the same white-blonde hair as his father and his half-sister, JonBenét. © John Ramsey.

While JonBenét had naturally light brown hair, it often turned blonde from the summer sun and darkened just a little in the winter. According to Patsy, she sometimes had her daughter’s hair professionally rinsed and conditioned in order to get rid of the greenish tinge it acquired from chlorine when JonBenét spent a lot of time swimming in pools. Patsy also told John and a friend at one time that she had JonBenét’s hair “touched up and conditioned” because it had been bleached white from the sun.

Both John as well as Patsy’s sister Pam, have said that Patsy never colored JonBenét’s hair, nor had it colored. According to Melinda, JonBenét’s half-sister, “That is just something they wouldn’t do because she was a child.” John added, “It’s just not something we would do.”

Yet, according to the JonBenét Ramsey Murder Book Index, one of Patsy’s best friends told police that, during the Christmas party at the Ramsey home on December 23, 1996, “[She] also noticed that JonBenét’s hair was died [sic] blonde” or “appeared really bleached out.” (BPD Reports #1-229, #5-4724.) This was the only allegation obtained by police from someone who knew the Ramsey family that JonBenét’s hair may have been dyed blonde at any time.

“JonBenét and I could practice dance routines together and design costumes,” Patsy explained. “I didn’t think of it as anything negative because it was part of what I had experienced as I grew up in the South and it seemed positive and fun. The picture the public got was from the beauty pageant videos that were aired continuously. It seemed she was a child whose life was 100 percent beauty pageants because the only pictures and video available were of the pageants. But that was really a small part of her life and who she was.”

Susan Stine shared school carpooling duties with the Ramseys. Burke, JonBenét and the Stine’s son went to High Peaks Elementary School, part of the Boulder Valley School District. “There was no dress code,” Stine said, “so JonBenét would mostly wear sweatpants, play pants, t-shirts, turtlenecks and sweatshirts. The school was very casual, and so was she. She never wore make-up to school.” Dresses were for the rare school pictures or end-of-the-school-year events.

Another friend of the Ramsey family said that “many of the parents, after the murder, had commented that JonBenét just looked like a regular kid at school.” She “would often wear just jeans to school.” This friend explained that many parents of students at the school had not known JonBenét was involved in child beauty pageants before seeing the Ramseys’ daughter in the child pageant video aired on the news.

Patsy’s attorney, Pat Burke, offered this insight regarding the effect of JonBenét being in child beauty pageants and its relationship to public doubts about Patsy: “Show me one thing, honestly and objectively, that you would ever criticize about her. The honest response is that some people criticize her because she put her daughter in beauty pageants. Yet that was what Patsy was raised doing. That was the culture of her upbringing in West Virginia. To her growing up, it was a good experience that improved her self-confidence and brought her closer to her mother. The worst thing people would be able to say about Patsy was that they didn’t like it that she put her daughter in beauty pageants.”

In addition to the pageants, JonBenét liked skiing, skating, rock climbing, piano lessons, and just being and interacting with friends and family, according to both of her parents.

She liked to be part of whatever was going on. On one Thanksgiving, when the whole family was going to her Uncle Jeff’s home, each family was going to bring a side dish. JonBenét insisted she bring her own food to share. She brought white bread rolled up with jelly inside, which she made herself with a bit of help from her mom. She called them “jelly roll-ups” and watched carefully to make sure everyone at the dinner had one. Patsy smiled remembering how she was JonBenét’s assistant that day. “I loved all my children dearly, and I sure was happy having that little girl telling me how to help her make jelly roll-ups.”

“She was always going full speed and laughing and smiling,” JonBenét’s dad has said.

Her Uncle Jeff said JonBenét was a loving, sweet, normal little girl who just wanted to do all the things other little girls did. “I cannot remember her in any pageant clothes or dresses. She was just a typical little girl in jeans and a t-shirt, dressed up in a little-girl dress only for a special occasion like Thanksgiving or Christmas.”

Uncle Jeff is one of John’s best friends. Because Jeff lived in Atlanta and John and his family lived in Boulder, their families didn’t see each other as much as they would have liked. But his memories of his niece are of a little girl who adored her big brother and loved playing with him and his friends, her little friends, and any adult who would agree to play her “kids” games like hide-in-the-leaves or hide-and-seek.

JonBenét was “very smart and talented, wise beyond her years,” her dad remembers. “She had unusual insight. If I came home from a particularly rough day at work looking serious, she would notice and tell me, ‘I don’t think that’s a good face to wear, Dad. I think you should smile.’

“She was very aware of people around her,” John added. “She loved the colors of flowers, the fragrance of them and was always surprised when some of them that were so pretty had thorns on them.”

Family friend and business attorney Mike Bynum didn’t know Burke and JonBenét well, but he once spent several days in Charlevoix, Michigan, where the family had a summer home.

“I went sailing with them on Lake Charlevoix where, even though they were six and nine, both kids had jobs on the boat. Both were treated with respect and showed respect back to their parents.” Sailing was another family activity that was important to both John and Patsy.

When John and Mike had to leave Charlevoix on business, Bynum says JonBenét was upset that her dad was going. The two stood for a few minutes in the entryway of their home in Charlevoix. “He got down on one knee and gave her a big hug and then talked with her about why he needed to go and when he would be back,” Bynum said. “He was on her level and talking with her face-to-face. I was impressed with the interaction between the two of them.” Bynum remembers the picture of them, down on the floor, talking it out.

When police interviewed JonBenét’s teachers after her murder, her homeroom teacher said: “JonBenét was a most unusual gifted student who was very humble and compassionate. Other children loved JonBenét and she was a very sweet girl.” That teacher said she was only vaguely aware that her student may have been in some sort of pageants. JonBenét’s music teacher said JonBenét was a “very humble little girl and very poised and very non-assuming. Not boisterous or egotistical. Very caring and compassionate. No signs of abuse.” And JonBenét’s art teacher described her as a “very mature” student who “seemed to be very normal.” (BPD Reports #5-3145, #5-3150, #5-3437, #5-3355, #5-3146, #5-3375.)

JonBenét’s teachers were equally enthusiastic about Patsy Ramsey. “Patsy was a volunteer that was a teacher’s dream,” said JonBenét’s homeroom teacher.

In a basement in a home in a Southern town, there is a room with JonBenét’s drawings as well as some photographs and clothing neatly stacked together. There are costumes from her pageants. The room gives off a wisp of loss that grows as one continues to look at the items this little girl left behind. On one piece of paper are words she printed: “Mom,” “Dad” (with a sailboat after her dad’s name), “Cat,” “Dog,”

“Boy,” “Bat,” “Burke,” and then “JonBenét” in her own cursive style. There’s a smiling face after her brother’s name and a hat after hers. The words give a sense of promise.

There is also a cut-out Christmas tree on a paper sack. The decorations on the tree are bright shiny dots of red, green, lavender, gold, silver and blue. Glue has soaked through and whitened parts of the tree, and then there’s her name at the bottom, something she was just learning to write at the time. One can picture her head bent over her drawing, brow furrowed in concentration, working proudly on this Christmas creation of hers.

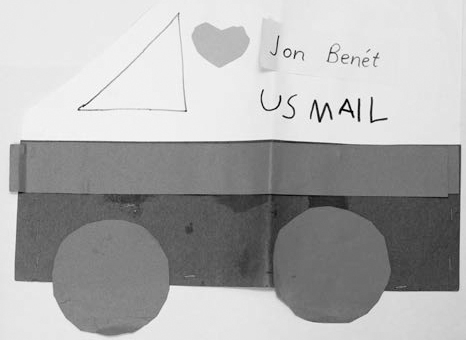

Or there’s the construction-paper US Mail truck; the whimsical drawing with several suns; the finger painting in bright yellows, blues, greens and pink; the ever-present smiling sun in other drawings shining down on cheerful flowers. There’s what might be a self-portrait of a blonde girl with blue eyes, a pink dress and a big smile, created seven months before JonBenét’s murder. She was just a little girl. And the impact of her loss only grows stronger as one touches what remains of what she created.

JonBenét’s handwriting. © John Ramsey.

Christmas tree cutouts by JonBenét. © John Ramsey.

US Mail Truck by JonBenét. © John Ramsey.

By JonBenét Ramsey. © John Ramsey.

Finger Painting by JonBenét Ramsey. © John Ramsey.

A big sack filled with Beanie Babies including turkeys, pigs, giraffes and a lamb sits abandoned on the floor. JonBenét’s dad searches through them with care. Toys and kid stuff, a pair of baby pajamas and other clothing emerges. He studies the packed-away pictures from so very long ago. As he looks at what is left, John says, “This is just a fraction of what we lost because of the incompetence and stupidity of the investigation. This is what’s left of our child.” And he turns away for a brief moment to compose himself.

Never again would his little girl find the contentment of a job well done, the warmth of the summer heat, the determination of building sand castles on the beach, the happiness of playing with other children just like her.

No one would ever call her “Mom.” Her lifetime lasted just six years, four months and twenty days.

In the years since his daughter’s death, John Ramsey has stated “it was a mistake to have JonBenét in the pageants.”

JonBenét’s Beanie Babies. © John Ramsey.

“I was persuaded at the time by how much she enjoyed it,” he said. “I didn’t realize that this might be where her killer found her.”

“She was too young,” he added, “and even though we emphasized that her talent was what was important in her participation, and she loved doing it, this wasn’t what was the most positive for her with the emphasis on looks and make-up. Patsy and JonBenét were doing it just for fun. Looking back, I was not pleased with the competitive environment in that many of the parents there seemed desperate for their child to win and that was quite different than why I believe Patsy and JonBenét were participating.”

The anti-public sentiment about child beauty pageants has increased internationally with, in some cases, harsh consequences. In January 2014, the French National Assembly passed a law that banned child beauty pageants as part of a larger package of women’s rights initiatives. The new law, which stated that girls under the age of thirteen were no longer allowed to participate in beauty pageants in France, included a carefully detailed description of “child beauty pageants.” There is a criminal penalty for violating the ban. Child beauty pageants have been banned in the Russian city of St. Petersburg as well, and some Russian lawmakers have sought a nationwide ban. Meanwhile in Australia, activists have protested against an American company that has brought its competitive style of child beauty pageants to the city of Melbourne.