CHAPTER 21

PUBLIC REACTION

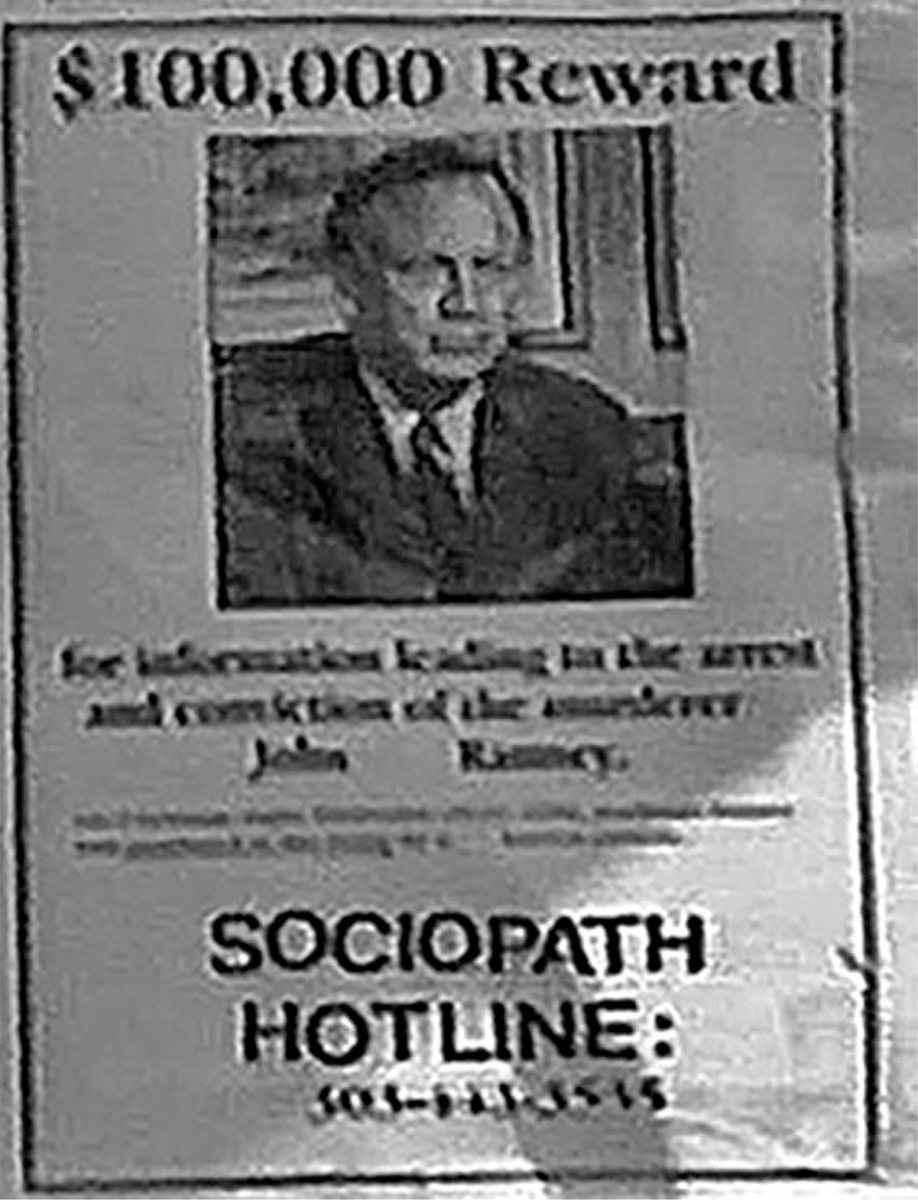

Wanted flyers of John Ramsey posted throughout Boulder in 1997. It was never discovered who made and posted them.

TO SOME, WHAT IS EXPRESSED AS SELF-RIGHTEOUS INDIGNATION can be received as the cruelest of attacks. By early 1997, John and Patsy Ramsey had become fair game for anyone with access to a computer, a telephone or any other vehicle through which they could voice their opinion to the media or general public.

On March 4, 1997, a local radio station disc jockey from KBPI erroneously told his audience “an arrest had been made in the murder” in reference to the Ramsey case. He later said this had been a prank and not true, but his statement provoked enough interest that newspapers as well as television and radio stations immediately reacted. A new barrage of chaos occurred with the Ramseys once again enduring requests for interviews, knocks on the door of the home in which they were temporarily living and visits to Burke’s school by members of the media.

On March 13, 1997, the Daily Camera newspaper published a story with the headline:

“A 10-foot-by-25-foot mural presenting three beauty pageant portraits of JonBenét Ramsey beneath the words ‘Daddy’s Little Hooker’ sparked anger and controversy at the University of Colorado this week.”

John Ramsey felt sucker-punched. “I just didn’t understand how something so terrible to our daughter’s memory could be considered as an art project displayed on the university campus.” He wrote a letter to the art student explaining his feelings about his daughter’s death but said he never received a response. The art student, a CU senior, had told the Daily Camera that he created the mural in order to expose child pageants. “This is a rich and powerful family and they’re manipulating all the resources for their benefit,” he added. The University of Colorado Fine Arts Department said the artwork fell under the constitutional protection of the First Amendment so they would not remove it, though it was eventually taken down.

In 2011, the art student was an editor for Middle Eastern issues and the principal editor with an information technology company when he responded to my 2011 request for an interview about his “Daddy’s Little Hooker” mural. I asked if he considered that the mural had been appropriate and fair. His reply included the following excerpt:

I lived several houses down from the Ramseys prior to the murder and I saw JonBenét frequently when I walked to university. She was a young girl who played and ran around like any other six-year-old. So like everyone, I was shocked when I learned of the murder. But that shock turned to disgust when the images of her pageantry life began to emerge. I found it increasingly difficult to reconcile two images in my mind: JonBenét innocently riding a tricycle outside her house, and her being dolled-up by her parents with makeup and suggestive clothing. My instinct told me there was something deeply troubling in that family. Whether or not one of the parents was involved in the murder, I am convinced the way they paraded JonBenét around as a beauty queen was a key factor that led to her demise.

“Amplifying that belief was the core justification for my art project,” he added. “Although it came off as hurtful and sensational to some, I believe it was an appropriate artistic response to the array of issues that the murder provoked.”

Negative publicity and hostility against the Ramsey family continued to grow. On May 8, 1997, the Daily Camera reported that fake reward posters for John Ramsey were being posted around the city:

“The fliers —patterned after a reward advertisement—began appearing on kiosks downtown … ”

In June 1997, a man named James Thompson (aka J.T. Colfax) started a fire in the Ramsey family’s empty home by igniting paper and pushing it through the attached mail slot next to the front door. (BPD Report #1-996.) He then reported himself to police. Thompson also admitted to stealing the original log-in page with JonBenét’s information from the mortuary where her body was taken. (BPD Report #1-996.)

In August 1997, someone phoned in a report to the Charlevoix, Michigan, police station saying John Ramsey had committed suicide. The family was staying in Charlevoix until their eventual move to Atlanta. When Charlevoix police went to their home, Patsy came to the door. They told her, “We have a report that John committed suicide.” Patsy wasn’t concerned, answering simply, “Oh no, he’s fine. He just left to go down to the lake.” The police then went to the dock to check on John and told him what had been reported. They apologized and were “very considerate,” John later said. It was impossible to track the source of the call, but the false report spread quickly on the Internet and into the mainstream media. Friends and family called that day, frantic because they had been asked by the media if John had killed himself. John would later state that he imagined “a tabloid reporter phoned it in just to create a stir again in the case.” The “suicide story” was reported the same day that JonBenét’s full autopsy was released, reporting in detail how she’d been killed.

In October 1998, JonBenét’s tombstone at her burial site was defaced after Boulder District Attorney Alex Hunter announced there would be no indictment following grand jury proceedings related to the case. Painted on her gravesite were the words “No Justice in the USA.”

According to employees of a fire station located near JonBenét’s gravesite, a tabloid news organization had tried to bribe employees of the fire station for information on when the Ramseys visited the site. The fire department employees said “no” and told the family of the attempt.

Local and national gossip shows on television and radio, columns in mainstream newspapers and, of course, the tabloids, continued to howl and hate. Some hosts significantly boosted ratings and profited off the killing of a child by making sure JonBenét’s murder remained an everyday sensation. While this momentum couldn’t be supported by factual information in the Ramsey case, that hardly mattered. Anti-Ramsey tirades beat on with whatever would entice, contributing to the ratings of any media outlet that would carry them.

National network evening news coverage of the murder of JonBenét Ramsey began on Tuesday, December 31, the day JonBenét was buried in Atlanta.1 CBS and NBC introduced the case to the nation. Both described JonBenét as a “young beauty queen” or as a “six-year-old beauty queen.” This was the most common manner in which all four networks would introduce her through the fall of 1997. National newscasts continually aired video of JonBenét performing in pageants. In some cases, television shows slowed the video down in order to exaggerate her movements while she performed, and some national tabloid television shows added suggestive music to the videos.

By calling her a “beauty queen,” the media allowed the public to easily categorize JonBenét Ramsey not as a six-year-old, but as a more suggestive child beauty contestant. This shorthand helped the networks sell the JonBenét updates to viewers and prompted less compassion for the dead little girl. It also suggested that JonBenét had been somehow responsible for drawing interest to herself, and perhaps even unwittingly drawing in her own killer. This reasoning runs along the lines of asking a sexual assault victim what she was wearing when she was attacked, which suggests that the victim may have “brought this on herself” or even “asked for it.”

When the media’s coverage of the Ramsey murder case first began, the Boulder Police Department was criticized publicly for botching the case. But that coverage was not nearly as dramatic and lasted for only weeks. Simultaneously, BPD officials began leaking details implicating John, Patsy, Burke or John Andrew Ramsey in the case, causing the victim’s family members to become instant media targets.

To add to the growing media circus around the Ramsey murder investigation, most “experts” booked on talk shows and quoted in newspaper columns related to the case were anti-Ramsey and not involved in the investigation in any way. Little verification of the accuracy of statements made by such “experts” was done, creating an open forum for uninformed opinions. The hosts interviewing such experts on broadcast shows would also slip in damaging buzzwords like the “secret room,” one of the rumored names for the storage room where JonBenét’s body was found, in order to influence listeners and keep them coming back for more.

The constant smears and false charges against the Ramseys piled on top of each other in several different public formats. In the years 1997 and 1998, the 24-7 media cycle was still new, and show hosts were scrambling to fill their programs with material that would pull in ratings on a daily basis. The listeners and viewers of these shows didn’t always understand that such broadcasts constituted entertainment, where anything goes, and not news, where accuracy is normally verified. And in their race to salvage dropping circulations in the wake of the advent of 24-7 broadcast media shows, newspapers across the country followed suit by reporting every new detail related to the high-profile case that was getting so much time on the airwaves.

In November 1997, Geraldo Rivera held a live several-day mock trial involving so-called witnesses who were not formally involved in the Ramsey murder case. The “jury” was composed of Rivera’s television audience as well as officials who were not part of the murder investigation in any way. At the end of the mock trial, the “jury” found the Ramseys “liable for the wrongful death” of their daughter.

At the time of this mock trial, no one had been charged or arrested in the Ramsey murder case, and the parents of JonBenét Ramsey were presumed innocent. Yet Rivera created a public spectacle that in a sense “convicted” the parents of killing their daughter.

Rivera did not return requests for comment.

According to Al Tompkins, Senior Faculty for Broadcast and Online at the Poynter Institute for Media Studies, a preeminent leadership organization and journalism think tank that teaches excellence and ethics in journalism, there is no place for mock trials like the one held by Rivera.

“It has nothing to do with journalism,” Tompkins said. “And there’s no place for it in our judicial system. There’s no function in turning crime into an entertainment show. It’s ultimately harmful to the people involved and to the process of justice. I don’t see any value in doing something like that.”

Fourteen years after the murder of JonBenét Ramsey on November 16, 2010, Denver Post columnist and television critic Joanne Ostrow wrote a piece about reality shows. In the article, Ostrow referred to a reality show that featured “JonBenét look-alikes” without saying the show was about child beauty pageants. JonBenét had been murdered in a vicious and sadistic way. Fourteen years after her death, her name had become a toss-away line synonymous with child beauty pageants.

Ostrow later explained in a January 27, 2012 email why she used the term “JonBenét look-alikes.”

“I believe you are referring to something I wrote about cable network TLC giving up its reputation as the ‘Learning Channel’ and becoming something low-brow,” Ostrow wrote, “‘a repository for families with 19 kids, hoarders, polygamists, and Jon-Benét look-alikes.’ I referred, as millions of TV viewers know, to ‘19 Kids and Counting,’ ‘Hoarding: Buried Alive,’ ‘Sister Wives,’ and ‘Toddlers and Tiaras.’ The hyper-sexualizing of children in beauty pageants, depicted on ‘Toddlers and Tiaras,’ is a deeper subject than I was treating in that TV column.”

I wrote back: “JoAnne: My question is if you feel it is appropriate to use the term ‘JonBenét look-alikes’ for contestants in a child beauty pageant?”

Ostrow’s response: “I don’t feel the need to comment further.”

The tabloids were the most savage as they spread over their covers lurid JonBenét headlines and pageant photographs. Small disclaimers were hidden on the inside pages of many of these publications, saying the JonBenét photographs on their covers had been “altered” with added eyeliner and mascara, darker shades of lipstick on her mouth and blush on her cheeks.

Some of the photos purporting to be JonBenét and Patsy weren’t even them, but people made up to look like them. But the magazines didn’t clarify the substitutions.

Examples of these tabloid headlines included:

LITTLE BEAUTY ABUSED MONTHS BEFORE MURDER?

(Globe January 28, 1997)

BROTHER, 10, MAY KNOW WHAT REALLY HAPPENED TO JONBENÉT

(Star June 3,1997)

BEAUTY QUEEN’S BROTHER HOLDS KEY TO MURDER

(The National Enquirer June 3, 1997)

DA’S SHOCKING OUTBURST: Inside mind of DA: JonBenét Dad did it—but he’ll get away with it

(Star November 25, 1997)

I HEARD JONBENÉT DIE! Neighbor’s stunning testimony: JonBenét’s chilling screams filled my ears

(Globe November 25, 1997)

GRAND JURY TO CHARGE: MOMMY KILLED JONBENÉT

(The National Enquirer January 26, 1999)

JONBENÉT MOM BRAGS YOU’LL NEVER PROVE I DID IT

(The National Examiner September 28, 1999)

JONBENÉT: SHOCKING POLICE FILES

(Star October 5, 1999)

EXPOSED! SHOCKING SEX & BOOZE PARTIES IN JONBENÉT’S HOUSE

(Star October 19, 1999)

John’s Journal:

I stop by the newsstand to get something to read and staring me in the face is the Globe Tabloid with JonBenét’s picture on it with the headlines: Mother bought “murder weapon.” “11-year old-son hides evidence.” What a disgusting cancer we have allowed to prosper in our society! I take the papers and bury them behind the rack. This stuff hurts and it outrages me that people like this with no morals or ethics are allowed to profit by exploiting the tragedy of a child with bald-faced lies. All under the umbrella of the first amendment and the legitimate media who have set a respectable standard.

With regard to such coverage, Patsy said, “John shields me from most of the publicity, but occasionally I see a tabloid with our daughter’s photograph on the front, and I just can’t breathe, you know, for a few seconds.”