I was born in the spring, and I never got over it. I am obsessed by seasonal changes; am far too susceptible to the blahs as daylight hours shorten in autumn, get a little too high for my own good when the evening light lingers. I love plants—the way they look and smell, leaves crisp in fall and flower buds bursting into bloom in spring.

Passersby may call any landscape a garden, but a well-trimmed lawn and tidy flower bed are not evidence of a guiding hand. The soul of a garden is an expression of its guardian, the person who orchestrates arrangements of plants; plans as they grow, thrive, or die; and constantly refines the picture. If you never moan about how much time it takes to garden but wish you had more time to spend in the garden, you probably are this person. If you’ve come to a point in your gardening life when your dreams outpace your means, if you would just as happily grow dozens of the plants you need as purchase a few from the garden center, and hope to grow your own foods, you are ready to make more plants.

Long ago, I learned the necessity to know each plant as an individual in order to help it grow; and when I needed many plants, I had to discover more about them. I had to become aware of the way plants work, and their place in the world. Then, I thought, I could practice the magic of propagation.

In 1996, I started a new garden beyond the confines of the narrow yard behind my Brooklyn town-house. I had been searching for a place in the country, where I could garden by the acre. Months of hunting in the area passed, and on a cold rainy day in December, I took what was to be my last exploration into the countryside. Friends Louis Bauer and Petie Buck came along, and after hours of driving and walking, we were hungry and tired and our clothes were damp. My companions moaned when I said there was just one more place to see.

As we drove down a steep hill and around a sharp turn in the road, Petie sat up and said, “This is it.” We were coming to a one-lane bridge over white water to the site of the new garden: 2.6 acres with a house on an island in a river.

I dreamed. I shopped for plants. I negotiated. And five months later, the first moving truck arrived, completely filled with plants. These first arrivals were barely enough to start the new garden, for as I planned and plotted my designs, I realized I needed many, many more. Because of cost and rarity, and just for the reason that some plants beg to be propagated, I began producing my own. And, like every gardener discovers, making more plants is one of the most rewarding, exhilarating, and addictive aspects of our passion.

An early planting was called “the buff border” for its flowers in tawny tones—cream to chamois to toast. I hoped a restricted palette might curb my shopping frenzy, but I didn’t stop to think exactly how few flowers are available in these colors. My desire intensified. Reference books and horticultural journals yielded names of promising genera such as the more esoteric foxgloves —Digitalis lanata and D. ferruginea. And I surprised myself when I turned to vintage bearded irises, plants I’d long overlooked. I hunted through old catalogs for mentions of forgotten varieties and out-of-fashion oldies, and I lingered over descriptions of blossoms with butterscotch or copper tones, such as ‘Tanbark’, which bears flowers in the colors of crème brûlée. Finding the plants themselves, however, was much harder. But if I am at the right place at the right time, when gardener friends need to divide their iris plants, they generously give divisions away.

I know that I am not the only person who has been turned on by propagation. I walked into the kitchen of Saida Malarney’s house in a suburb of Detroit and noticed, instead of houseplants on her windowsill, five plastic saucers. A friend had gotten her hooked on starting ferns from spores. In a town nearby, Betty Sturley, a painter who specializes in flower portraits, was propagating annuals and perennials for the church bazaar. In an adjoining town, the annual home gardeners’ perennial swap was slated for that weekend. There was a picture in the newspaper from the previous year’s event in which a boy was wearing a sandwich board that read: “Got Heuchera. Want Hellebore.”

If like that young man, you receive a piece or pot of something wonderful to nuture when you get home, you will have a lasting reminder of a place, a time, or a friend —as sentimental as a postcard —a living memento.

Ever since I saw can delabra primroses at North Hill, the Vermont garden of the late Wayne Winterrowd and Joe Eck, I wanted to grow them on the banks of the canal that cuts across the island. I started with a few plants in a few colors. To have more shades, I would have to grow plants from harvested seeds. I wondered if the seeds would germinate on their own if scattered around the parent plants, so I asked Wayne about his experiences with the same Asian Primula species and hybrids. His first comment was a general one about propagation: “It’s so different for everyone,” he said. As for the primroses, his do not seem to appear from seed on their own. In March, he prepares a flat of sowing-medium for a mass sowing of the seeds. The resulting seedlings spend their first Vermont winter in a cold frame. Then they are planted among the other primroses.

It was encouraging to hear Wayne talk of diverse experiences and varying practices in propagation, because such things are encountered time and again. That was also proved by something else Wayne said about our primroses: “The one thing I know for sure about the Primula is that they cannot be divided.” He’d tried without success. “They melt, they rot, they disappear,” he explained. Oddly enough, I’d been successfully dividing my primroses since my first half-dozen plants were in their second spring. When the growth is about 1½ inches tall, I dig the plants, rinse them off in the canal, pry the little side shoots away from their parents, and transplant them. The plants bloom about seven weeks later. By their third spring, there were too many to count.

Wayne applauded what he reasoned to be a special technical proficiency. But that is not necessarily the case. My success is due more to one thing we certainly agreed upon —the timing is crucial. I’d recognized the precise moment to operate, when the plants were beginning their surge of growth and were most eager to generate new tissue.

With an open mind and eyes wide, I have tuned in to the bio-rhythms of the plants in my garden and, without much deliberation, drawn the right conclusions —what might be called “learned intuition.” Through propagation, I’ve learned to appreciate the life within a seed, the promise of a stem cutting or a piece of a bulb; it’s the thrill of life beginning, and irresistible to anyone who loves to watch plants grow.

I want other gardeners to know how it feels to sow a seed or root a cutting and watch the results grow to maturity, to experience the freedom and convenience of being able to produce plants in numbers. Enough of the craft and science of propagation can be learned in this book so that anyone with curiosity, practice, and a little luck can master some of nature’s skill. You will read about each step and witness them in photographs, taken over three years of performing the magic of making more plants for the garden.

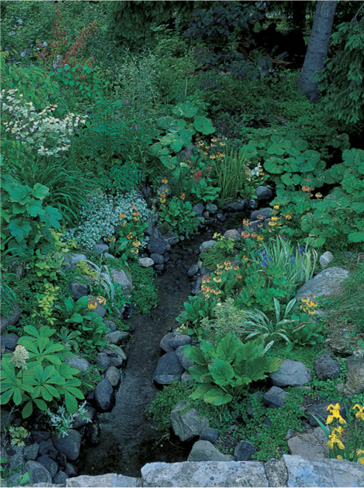

The fast branch of the river that runs around the island site of the new garden.

New gardens need plants—lots of them. Wonderful ones come from friends, such as this fawn-colored iris. A piece of a rhizome for Iris ‘Aztec Gold’ came from the Wenbergs, who garden at the top of the hill.

The canal garden (shown in its third spring) was planted with perennials and shrubs from seeds, cuttings, layers, and divisions. Every spring, around seven weeks prior to blooming, many of the candelabra primroses are dug and divided.

June’s glowing display features scores of these Primula x bulleesiana that began as a half-dozen mail-ordered plants. However, in order to expand the color range, the genetic diversity, seeds from harvested fruits had to be sown.