People have called Cincinnati many names: Porkopolis, Queen of the West, Queen City, Blue Chip City and the City of Seven Hills. But the city along the Ohio River that was founded in 1788 got its final name from a famous ancient Roman general named Cincinnatus. Many considered Cincinnatus, who lived roughly from 520 to 430 BC, to be a hero for defeating the Aequians, Sabinians and Volscians—and then resigning from the dictatorship he had rightly won to rule only his own farm.

Cincinnati resembled pioneer-era cities such as Pittsburgh and Nashville, riverboat towns like St. Louis and New Orleans and immigrant-industrial metropolises similar to Brooklyn, Philadelphia, Chicago and Detroit.

Cincinnati consisted of a large area, with the Ohio River forming the southern boundary and the hills to the north enclosing its basin. Initially, people and businesses set up in the basin of the city, near the river, because it could be harnessed for energy and transportation of goods and people. The introduction of steam navigation on the Ohio River and the completion of the Miami and Erie Canal helped the city’s population grow.

The city limits stopped at Liberty Street, and the area above it was known as the Northern Liberties because it was not subject to the laws of the city. As such, it drew a concentration of bootleggers, saloons and entrepreneurs. In 1848, the city annexed the area as its first “suburb.”

The city considered itself a jewel of the Midwest, and to prove it, it held industrial expositions every year from 1870 to 1888 to showcase invention, trade and the arts. These gatherings proved that Cincinnati was a center of music, art and industry.

Cincinnati was one of the first American cities to be home to a zoo. The Zoological Society of Cincinnati was founded in 1873 and officially opened the gates to the Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden in 1875. At the time, its animal collection was very small: just a few monkeys, grizzly bears, deer, raccoons and elk but an impressive collection of birds, including a talking crow.

The city also played home to a professional baseball team: the Red Stockings who eventually went on to become simply, the Reds. In their first season in 1869, they went undefeated.

The city became an important stop along the Underground Railroad in the pre–Civil War era because it bordered on the slave state of Kentucky. Historical papers often mention Cincinnati as a crucial stopping place for those escaping slavery.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, public markets represented the primary source for buying and selling perishable food in Cincinnati, as they were in other urban centers. Butchers, farmers and produce vendors gathered under one roof to sell their wares to residents who lived within walking distance of the markets. These markets also became places to socialize and for public meetings. At one time, Cincinnati had as many as nine public markets in different areas of the city. But as the trolley and incline systems were constructed, people moved from the basin of the city to the hills. On each hill, neighborhood businesses, including grocery markets, popped up. The only remaining public market in Cincinnati today is the Findlay Market, near the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood.

In the late 1800s, Cincinnati was governed by a system of wards that lent themselves to corruption. From the 1880s until the 1920s, the Republican machine of Boss Cox primarily ran the city. By 1924, a new politician, Murray Seasongood, had instigated the ballot system to eliminate the corrupt wards.

The city was also the birthplace of two United States presidents. Benjamin Harrison, the twenty-third president, was elected in 1888 (at which time he resided in Indianapolis, Indiana). William Howard Taft was elected in 1909. The Tafts became a major political family in Ohio, with the president’s son and grandson both becoming U.S. senators and his great-grandson, Bob Taft, being a two-term governor of the state.

People who came to America from different countries settled together in neighborhoods such as Over-the-Rhine for Germans and the West End for Eastern Europeans, especially Jews. In many neighborhoods, workshops, homes and businesses stood side by side. To accommodate the growing population, developers created “French flats,” which, instead of being just sleeping rooms, were more traditional apartments that included private bathrooms and kitchens.

But the densely packed population in these areas created poor sanitation conditions that led to a cholera outbreak in 1867. To help ease these conditions, Cincinnati constructed suburban parks, new waterworks and broad avenues out of the city.

Despite the city’s flaws, which were the same found in most urban areas at the time, to Louis Charles Graeter, Cincinnati was a haven.

Born in 1852, Louis Charles, son of immigrants from Germany, left his home in Madison, Indiana, as a teenager and moved to the Queen City. His grandchildren say they were told the young Graeter left home because his father, a barber, was “so mean to him,” a quality they considered to be “typical” of their German heritage. Time would prove that the Graeters had a long history of being strong-willed, opinionated and not likely to shy from arguments.

Louis Charles landed in Cincinnati and began to sell ice cream at a street market at the base of Sycamore Hill. Making ice cream in those days was a painstaking—and expensive—process. Graeter made the treat by stirring it by hand in a metal pail set in a bucket filled with ice and salt, two expensive and hard-to-come-by items. The concoction had to be eaten almost immediately because there was no way to store it. Ice cream was, in those days, still considered a novel delicacy.

Graeter’s Ice Cream was a newsworthy company in 1883, when the Walnut Hills News ran a blurb that stated: “Graeter’s Ice Cream business is opening unusually good. He keeps two wagons engaged in delivering and three men employed in making his delicious creams.”

But about the same time, Louis Charles decided that Cincinnati and the domestic life he had created with his wife, Anna, didn’t suit him. He took $1,000 from his bank accounts and left his wife with the ice cream business and a fair amount of debt.

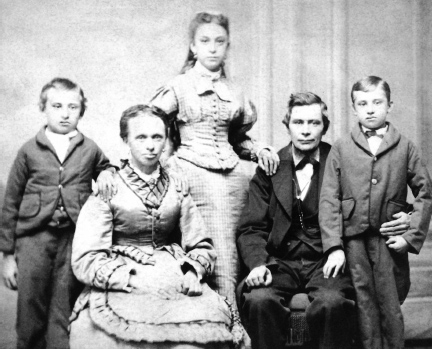

The Graeter family of Madison, Indiana. Young Louis Charles is on the far left. Courtesy of Graeter’s Ice Cream.

Louis Charles set out to find his fortune in Stockton, California, where he married again. A different state and different faces offered only the same results for Louis Charles. Around the turn of the century, he left California and again returned to Cincinnati.

Louis Charles’s brother, Fred, who had followed him to Cincinnati years earlier, was perhaps more noble than he. Fred had maintained the business and gotten it out of debt while Louis Charles was on the West Coast. When Louis Charles returned, Anna was gone, but the business was intact, so he resumed making ice cream in the French pots.

Maybe the hope for love knows no limits, or maybe the third time really is a charm, because Louis Charles again tried his hand at marriage. He wed Regina Berger, who was the daughter of prominent Cincinnati businessman Anton Berger. Anton was an upstanding man in the community, president and general manager of the Julius J. Bantlin Company, which manufactured saddlery and hardware. Regina, his third child, was twenty-three years younger than her new husband. It appears that in Regina, Louis Charles had met his match.

Louis Charles Graeter, founder of Graeter’s Ice Cream, was born in 1852 and moved to Cincinnati as a teenager. Courtesy of Graeter’s Ice Cream.

The couple set up a home at 967 East McMillan Street in the Walnut Hills district of Cincinnati, a section at the top of the Main Street incline, one of the city’s trolley systems. Louis Charles operated Graeter’s Ice Cream out of their flat, cranking out the ice cream in the back room of the bottom floor and selling it out the front. Louis Charles and Regina lived in the upper floors. This store remained in operation until 1972. The property was sold in 1974.

Regina Berger (left) was the third wife of Louis Charles Graeter. She was twenty-three years his junior. Courtesy of Graeter’s Ice Cream.

“There were a lot of companies like this in Cincinnati. They made it in the back room and sold it out the front door,” said Lou Graeter, grandson and namesake to Louis Charles. “That’s the way they ran the business. And they ran the business a long time that way.”

To make the ice cream, Louis Charles still used what was called a French pot freezer, a handmade metal bowl that looked like a cylinder and sat inside a wooden bowl filled with ice and salt. Louis Charles filled the metal bowl with a mixture of cream, sugar and eggs.

“That pot would spin the mix and force the product to the sides and it would freeze,” said Dick Graeter, another of Louis Charles’s grandsons. “Then a person would stand there with a paddle and scrape that off the walls of that freezer until it all came together and was frozen.” To spin the pots, Louis Charles lined them up and hooked them by a pulley to a single motor overhead.

In addition to ice cream, which was primarily a summertime treat at that time, Graeter’s sold chocolate confections and various knickknacks. Dick remembered:

At that time, we sold novelties, too. A lot of ceramics. In those days you didn’t have all the gift stores and all these other places selling all that stuff. That was another thing that was an extra sale that you had in the wintertime when you weren’t selling ice cream. All retail people are always looking for something else to sell, something that will pay the rent.

Grandma always did that. She would go to New York a couple times a year and buy all this stuff and bring it back. And she’d send it to stores as part of the candy cases, different novelties, even toys and things.

Life was cut short for Louis Charles in 1919 at the age of sixty-seven, when a car struck him as he exited a trolley.

It was a scary time for Regina, who was left with two young sons, a business and not even the right to vote (which wasn’t granted to women until the following year). The world was in the midst of its first world war and the largest flu epidemic in history. The war claimed an estimated sixteen million lives, while the flu that started in 1918 killed fifty million across the globe. A fifth of the world’s population, and a quarter of the people in the United States, contracted the disease.

Cincinnati was changing during this period, too. A wartime shortage of labor and poor economic and social conditions in the southern states drove people north for factory jobs. Cincinnati became home to a large black population who settled primarily in the West End. While many were poor, black entrepreneurs settled in Cincinnati, too. Businesses such as a jazz bar called Cotton Club, which many say rivaled the club of the same name in New York, brought celebrities to the city and helped improve its image as an arts center in the Midwest. In later years, such notables as Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday sang at the club.

The same year that Louis Charles was killed, the Cincinnati Reds won their first World Series against the Chicago White Sox. The title was soon tarnished, however, because members of the Chicago team were suspended for purposely losing the series for financial gain.

Graeter’s was not the only family-owned ice cream business in town during this time. Thomas and Nicholas Aglamesis, who settled in Cincinnati from Sparta, Greece, started Aglamesis Brothers Ice Cream in 1908. The duo opened their first ice cream shop, called the Metropolitan, in Norwood, an eastern Cincinnati community. A second store in Oakley followed in 1913. The product was similar, though it was not made in French pots as Graeter’s was. And, unlike the Graeters, the Aglamesis brothers were content with their two stores.

Regina had a different vision for her business. Despite being a young widow, she was determined to persevere, not just continuing with the single store but expanding it. She opened the first satellite stores on Walnut Street downtown and then in Hyde Park, which became one of Cincinnati’s wealthiest enclaves. The store, which was originally part of Higginson’s Tea Room, stood in Hyde Park Square, which was developed in 1900 as a center for shopping and community identity. This store at 2704 Erie Avenue is still in operation today and is the oldest operating Graeter’s retail store.

The Graeter’s store in Hyde Park is the oldest of the stores still in operation. It opened in 1920. Courtesy of Ken Heigel.

To help with the family business, young Wilmer, the oldest son of Louis Charles and Regina, dropped out of school in the eighth grade, because he was more interested in driving a truck, his son Dick said.

“If Wilmer was around today, he would be one of those kids labeled ADHD,” Dick said. “He was really smart, he just didn’t do well in school.” But he was, Dick remembers, very creative and artistic, an unusual combination of characteristics for someone who worked with his hands.

His younger brother, Paul, on the other hand, finished high school, though he didn’t go to college.

By 1929, Regina had opened six new stores in Cincinnati, including ones in Norwood, Madisonville, Avondale and Pleasant Ridge. To manage the volume of ice cream needed, the company purchased a manufacturing facility on Reading Road in Mount Auburn in 1934 during the height of the Great Depression. The family turned a building that once housed an old printing press into an ice cream and chocolate production plant. All of the ice cream for the retail stores started being produced on Reading Road in 1937.

The back of a tally sheet from the 1930s lists store locations at the time. Courtesy of The History Press.

As history would prove over and over, people always made room for the little luxuries in life, such as ice cream. While other businesses faltered and failed, Graeter’s grew during the most difficult economic time in the country’s history.

By the end of World War II, Graeter’s Ice Cream included a network of stores that spanned Cincinnati. By this time, Wilmer and Paul were heavily involved in the business, but it was Regina whom everyone, including her sons, called “the boss.”

Her great-grandson, Richard Graeter II, believes she must have been a remarkable person, managing everything from the death of her husband to the business through two world wars and the Great Depression, at a time when most women didn’t work outside the home at all, let alone run a business.

“I never met her, but I owe her for everything I have,” her great-grandson Richard said, “because without her strength, fortitude and foresight, there would be no Graeter’s Ice Cream today.”