5

How to Become a Star: The Celebrity Network

In June 2008, on a hot summer evening, my friend Eric, who had been working tirelessly on Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, called to say he would be flying into New York City the next day for the senator’s speech after the Montana and South Dakota primaries. (This speech would be her last before conceding to Barack Obama.) Eric said that if I wanted to come—the event would take place at Baruch College with a fabulous-sounding after-party at the Gramercy Park Hotel—he would happily get me in. This was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up. I canceled my previous plans and the next day at six p.m. I made a beeline for downtown to meet him.

When I arrived, the place was already swarming with people and TV cameras, and there was still a line of supporters all around the block waiting to get in. (The real picture was far removed from the claims journalists made the next day that “barely 300 people showed up” and that the evening was “more like a wake.”) I got to the front door where Eric had asked me to wait for him. Of course, with all of the guards, Secret Service, and various Clinton staffers patrolling the front area, I had to make myself look really busy (with the aura of possibly being an important person), which involved frenzied and unnecessary e-mailing on my BlackBerry, thus avoiding all eye contact with people who could ask me to move away from the door or into the line.

Eric arrived just in time, sporting an open-collar white shirt and designer jeans, accompanied by days-old facial hair, looking ever the part of the hipster demographic that had only recently become a politically active and tremendously desired constituency. Slapping a bright yellow band on my wrist, Eric whisked me past some fifteen hundred people who had been waiting in line for hours and were probably going to be told the event was full. After going through a rigorous security check, we went down to the basement where the event was being held and watched the media flurry unfold. Random politicians and high-up staffers were talking to reporters. CNN and Fox News anchors were grooming themselves and talking into their headsets, ready to go at a moment’s notice. Socialites and supporters richer than Croesus sashayed about the VIP section, designer handbags and Lilly Pulitzer shift dresses on full display. Shortly before Senator Clinton was to appear on stage, Eric and a few of his staffer friends were busy ensuring I would get a good seat and then, later, get backstage access. Eric worked for her advance team, but more than five hundred media outlets and hundreds of supporters were showing up, so it would be tricky to arrange. Eric, however, was privy to what could only be described as “all-access” buttons, which would allow us backstage and get us into the most privileged parts of the event. These buttons were provided by the Secret Service in very limited batches for staff. And sure enough, Eric produced one from his pocket.

Once the access dilemma had been resolved, we went back to the VIP section (where I had to show my yellow wristband yet again) and awaited the senator’s arrival. The staffers were still discussing access and how to get non–advance team fans back to meet the senator. Eric turned to a fellow staffer, a young, pretty blond girl, and asked, “Do you have any of those media passes left? We’ll use those for backup.” With barely a beat between request and delivery, she proudly reached into her enormous Prada handbag and produced a handful of hot pink passes the size of index cards with Senator Clinton’s name emblazoned across the top and MEDIA in boldface on the bottom. Thanks to Eric and his friendly fellow staffers, there I was with backups to backups of access to see one of the most important public figures in the world.

Senator Clinton’s speech was impassioned and exhilarating in the way that television can never quite capture. The audience was transfixed while she spoke and erupted into thunderous applause as she finished. Afterward, we went backstage and were introduced to Hillary, Huma Abedin (her right-hand woman), Bill and Chelsea, the former head of the Democratic National Committee and head of the Clinton campaign, Terry McAuliffe, and every other significant member of the presidential campaign. Later that evening all those people (except Senator Clinton, who had to head to Washington, D.C., immediately after the event) attended the after-party at the Gramercy Park Hotel rooftop bar, mingling and chatting for hours with the attendees.

This story makes it seem like access to the senator is easy, but in reality it’s impossible. You might think that if you stand in line long enough or keep showing up at the doorstep of important events your chances of befriending stars increases, but it doesn’t. Right of entry relies on one very good link. If that link is a legitimate access point (either a celebrity or someone who works closely with stars), then one has a ticket into an exclusive world. Without Eric, my chances of setting foot in the door of the auditorium, let alone meeting Senator Clinton personally and attending her after party, were zero. My success relied solely and totally on my friendship with Eric. But once initial access is granted, the next layer of connections is that much easier. Suddenly, by mingling at the Gramercy Park Hotel, you have all the access in the world to people who have the potential to elevate your profile too. Maybe you want to befriend them, become their boyfriend or girlfriend, or simply request their friendship on Facebook. No matter your networking goal, by accessing the party, you’ve never been closer to attaining it. A fundamental quality of celebrity is that celebrities are celebrities because they spend time with other celebrities, reinforcing the belief that they truly are different from you and me. This may be a story about one of the world’s biggest political celebrities, but the exclusiveness of the celebrity world can be mirrored in the most ordinary and small-scale ways: High school cliques and college sororities maintain their elite status similarly, except that parties at the Gramercy Park Hotel are replaced with Friday night sleepovers and private mixers with elite fraternities. By maintaining exclusivity in their social lives, these groups too produce their own relative celebrities. Understanding celebrity requires a knowledge of the social network that produces them. This may be an intellectual exercise for most of us, but in practical terms, those in the business of wanting to become celebrities must first make contact with those who have already achieved this goal.

But who cares? If a clique is that exclusive and that much of a pain to get into, then maybe it’s just not worth trying to become a member. In the last few decades, scientists and sociologists have devoted much of their lives to answering these questions. Why would anyone want to belong to a group? What are the real outcomes—both benefits and drawbacks—of being a member?

Most of us have friends. Some of us have a lot of friends who aren’t close, some of us have a few friends we hold near and dear. If we’re lucky, we have lots of friends who are loyal and close and on whom we can depend. On the most basic level, friends form a social network. Some of us have very tight groups of friends who are all friends with one another.1 Still others have tons of acquaintances who are not necessarily friends but make up a wide and disparate collection of people. Think of Malcolm Gladwell’s famous “connectors” (discussed in The Tipping Point), those people with friends on every continent. A lot of us have this type of large and very loosely connected friendship group on our Facebook account. I am “friends” with people I haven’t seen in years and also friends with my colleagues at work, my husband, and my best friend, to whom I talk every day. Even before social media websites, social networks formed our basic relationships with people around us.

But friendship isn’t the only type of social network. How we get jobs, how disease is spread, how websites become popular, and how people attain upward mobility are all determined by our relations and connections and interactions with other people. Our ability to interact with some people and some groups may provide benefits or may exclude us from other groups. Mean-spirited high school cliques that don’t let certain individuals in because they are friends with someone they don’t like are the classic example of exclusionary social networks. But in other ways, social networks are useful for meeting people who will introduce us to our future partner or spouse, get us a new job, write us a recommendation for college, and so forth. Studying social networks is a good way of understanding how the world is organized, another lens for interpreting a wide range of phenomena in human society, from why people marry whom they do, to how people become rich, catch a cold, or, in this case, attain celebrity status.2

Through the eyes of the media, mainstream celebrities look like beautiful people who are photographed a lot and who are generally sports stars, musicians, actors, or models. But another way to look at celebrities is as a members-only group: Celebrities are celebrities also because they get invited to certain parties and hang out with certain people. They are a part of a very elite invite-only network. Individuals attain celebrity in part by the company they keep and the events they attend—in other words, their social network.

There are benefits to being a part of an exclusive network. While all forms of celebrity exhibit this type of exclusiveness, most (though not all) mainstream celebrities get their foot in the door first by being associated with popular culture industries to some degree. Some of these individuals are genuinely talented actors or musicians, which buys them access to exclusive events. Others may not possess talent but their face and presence are of interest to the popular press and thus they are invited. Their talent or media attention is their entry to the world that would not take notice of them simply as individuals. And this is where the celebrity network is critical. Getting invited to and showing up at the right parties and meeting the right people are only the surface benefits of the celebrity network. If you’re an actor or a politician, meeting those important people at those exclusive parties is essential to your career. The Vanity Fair Oscar party, for example, is more than just hanging out with other beautiful people. Young actors get the chance to hobnob with influential directors who might remember them down the line and give them a role in a major film.3 Directors and producers talk shop about movie ideas that might turn into award-winning blockbusters. Even those stars with no talent (the all-residual celebrities) need to be at the events and parties that other celebrities are attending just to define themselves as a part of the exclusive celebrity set (and get themselves photographed). This entitles them to a membership card. For the Paris Hiltons of the world, membership in the exclusive world of celebrity compensates for the lack of an Academy Award or a Grammy. And if you are in show business to show the world your talent, then being a part of the most exclusive and powerful networks offers huge benefits.

Celebrity networks are influential because they are both the means by which celebrity status is perpetuated and they provide access points to important people who can elevate an aspiring star’s career. If we could infiltrate this exclusive world, could it tell us something more generally about how people become stars?

A few years back, my Ben-Gurion University colleague Gilad Ravid and I were determined to figure this out. We believed that celebrity status can partially be explained through specific networks of which celebrities are a part. But after establishing that theory we ran into a bit of a basic nonstarter: How does one get into the celebrity network in the first place? And after that, how does someone become a particular type of star?

We knew it would be unlikely that Paris Hilton or Angelina Jolie would fill out weekly surveys on their comings and goings, whom they had lunch with, what they did on Friday night, or whom they met up with for coffee. But we knew that one of the defining differences between celebrities and us is that they spend time with each other, and we spend time with, well, us. That exclusiveness is part and parcel of why it would be almost impossible to document their networks. Most of the point, after all, is that ordinary people can’t participate.

Luckily, Gilad is a genius computer scientist and I spend a lot of time reading celebrity magazines. Between the two of us, we figured out a way to access celebrity networks and the exclusiveness of their social lives without asking them a single survey question or trying to talk to Paris Hilton. A definitive aspect of being a celebrity is that your life is fascinating to many other people. And in the case of stars like Paris and Angelina, your life is photographed and documented around the clock, around the world. If many minutes of these celebrities’ lives are broadcast to the world in hundreds of media outlets and thousands of photos, wouldn’t this be the most obvious way to study their social networks and the things they do that are different from what we do? What parties do celebrities get invited to and which people do they hang out with? What is Paris Hilton doing on Friday night? Well, just a glance at the photos in US Weekly or People will tell you. So if we look at photographs of celebrities living their lives we’ll have a pretty good sense of whom they spend time with and what they do.

For an entire year (March 2006–February 2007), we studied all of the arts and entertainment photos taken by Getty Images, the largest photographic agency in the world. We analyzed some six hundred thousand photos of almost twelve thousand events, recording the 6.5 percent of individuals who appeared in four or more images—the celebrity core, so to speak. We then studied all the events they attended and people they spent time with. So far, we’d figured out a thing or two about the nature of celebrity.4

It came as no surprise that celebrities hang out with other celebrities and they go to events that the rest of us aren’t invited to. Celebrity tabloids love to breed the fiction that celebrities are “just like us.” But they’re not. Angelina Jolie goes to parties with George Clooney and Matt Damon, and those “get-togethers” happen to be the Vanity Fair Oscar party and the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute Ball, as opposed to Aunt Sally’s barbeque or Friday night bowling. These differences between celebrities and us are not just anecdotal, they can be statistically measured. Overall, looking at their social lives, we found two very important properties of celebrity networks that distinguish them from “noncelebrity networks.”5 First, there is nothing at all random about celebrity networks: They are connected simply by virtue of being full of celebrities. Second, being a celebrity reinforces itself. In other words, by spending time with other celebrities one gets the opportunity to meet lots of other celebrities and get photographed with even greater frequency, all of which increases one’s celebrity all the more. Or as Daniel Boorstin wrote in his famous book The Image, “[Celebrities] help make and…publicize one another. Being known primarily for their well-knownness, celebrities intensify their celebrity images simply by becoming widely known for relations among themselves.”

This may seem obvious, but social network analysts find this celebrity-begets-celebrity phenomenon to be a feature of special types of social networks not present in the average person’s social life. In general, studies of human behavior demonstrate that people’s interactions are random. Say we took an unbiased, random sample of people who live in Los Angeles and all the places they went during a year and all the people they spent time with. We would likely find that their social network looked quite predictable. Most people are connected because they are genuinely friends. If we look at more loosely linked networks, we can trace most people through regular routine (e.g., where they grab their coffee every morning or where they live or work) and find the same connections. There might be an interloper here and there, a random person we meet at a bar or bookstore and with whom we strike up a conversation. Most of the time, however, people’s connections make sense and can be explained by the people they are friends with, their hobbies, job, socioeconomic status, and the places they frequent. My friends are unlikely to be connected to my other acquaintances’ friends without my introducing them or unless all of us are working at the same place or are members of the same rock-climbing club.

Celebrities are different. Even those celebrities who are not friends, who are not related by occupation (for example, film stars), who do not live in the same place, who do not attend the same events, tend to be systematically, closely connected to one another despite having no real reason to be so. In a few very short steps, each celebrity can connect to anyone else within the network, even if they don’t attend the same parties. Just by virtue of being a celebrity, celebrities tend to be much more closely connected to one another. While most people are connected to everyone else in the world through the well-known “six degrees of separation” (which turns out actually to be true),6 our analysis of celebrity networks demonstrates that celebrities exhibit just 3.26 degrees of separation from one another.7

What this means in real terms is that multi-award-winning actress Kate Winslet, in all her elegance and regal glory, may actually be at the same event where girl-gone-wild Lindsay Lohan is stumbling around in the bathroom and Britney Spears is acting like a crazy person (again). And of course, Kate may say hello to Lindsay and Britney because they know each other by virtue of being at the same exclusive events, even if they have nothing else in common and have never (and will never, to be clear) costarred in a movie or sung a duet. Contrast this with the noncelebrity world: Most people with a predilection for hard partying and bad behavior aren’t likely to be running in the same circles as reserved, refined people like my mother. What makes celebrity networks so different from ours is that everyone attends the same events and knows the same people. Additionally, most celebrities’ friends tend to be connected to one another, by virtue of ending up at the same parties or being friends with people who end up at events where mutual friends are in attendance. This property can be observed in other tightly knit industries, like finance and publishing, and it can result in career promotions and making friends with important people within these respective industries.8 But such networks have different purposes from being a celebrity: If one wants to become a celebrity (rather than a CEO or publishing mogul), there is no better network than befriending people who are constantly photographed by the media.

Think about how most of our friendship groups operate: I may have one group of friends that consists of work colleagues and another of college buddies. It’s unlikely that these two groups will overlap. But in the celebrity world, people in different social groups are connected. By virtue of the exclusiveness and small number of people in total, there are many individuals who end up crossing multiple social groups, linking disparate groups. This property of celebrity social worlds has a resounding impact on the members’ networking capabilities.9 Because the people they are connected to tend also to be connected to everyone else, they are by default all connected to one another.

Sure, this makes sense when you’re looking at Hollywood film star A-listers, who all get invited to the same superexclusive events. But why would a New York socialite have anything to do with a famous Hollywood producer? In reality, they are as far apart as I am from a random lawyer who lives in New York. The tie they share is simply their celebrity status. By virtue of both being high-profile they are a part of the same network that connects both of them to Angelina Jolie, Paris Hilton, and the fashion designer Marc Jacobs. The socialite and the producer may not attend a single event together, but they are more likely than the rest of us to be friends with people who are friends with people who all attend the same events. Many of these people know both the producer and the socialite, and likely the producer and socialite at least know of each other even if they have never met. Despite being utterly different people, with different occupations, located in different parts of the world, members of the celebrity network are closely linked. On some level, celebrities are celebrities because their network defines them as such.10

The second important finding, which is correlated to the first, is that within celebrity networks people are much more connected than ordinary people like us. Every time you befriend one celebrity, you gain access to many more. Why is this important? Celebrity networks provide a huge benefit to people who can penetrate them. A popular saying is that the “rich get richer,” often accompanied by the statistics that 20 percent of people possess 80 percent of the wealth and that 20 percent of people use 80 percent of health care.11 This concept, also known as the Pareto Principle or, as Malcolm Gladwell calls it, the “law of the few,” demonstrates that a very small number of people get a huge number of benefits and is closely linked to the type of dense networks found among celebrities.12 In their famous Science article studying the World Wide Web, physics professors Albert-László Barabási and Réka Albert observed that these networks exhibit “preferential attachment,” which means that being a part of the celebrity network produces exponential benefits as someone within the network becomes increasingly connected.13 People meet people through their connections with other people. The people within a network that exhibits the property of preferential attachment tend to meet many more people through one connection than they would through everyday networks. I don’t have any connections to that Hollywood producer or any of the events he attends. So try as I might, the chance to talk to him about an upcoming role or movie is slim to none. Not so for that directionless New York socialite, who happens to be in the same network as that Hollywood producer, although she may never have gone to film school or even acted. She only has to pick up the phone and call one of her friends, who is friends with that producer, and very likely she’ll get him on the phone or be able to grab a quick coffee with him. It is that opportunity that is so important.

What does that mean in terms of celebrity? More media attention, more opportunities for roles in movies, record deals, and modeling campaigns. More access to people you might want to be in touch with. Greater chances to meet very important people who will further your career. And, of course, all of these interactions provide an opportunity to perpetuate one’s celebrity. The benefits of these connections are not simply access to more people; there are real advantages to one’s career and social status, what sociologists and economists call “positive network externalities”: Being a part of a network of celebrities increases the chances of meeting a high-profile partner, landing a major movie role, and getting photographed and featured in popular media outlets, all of which enable one to become a bigger star.14 The importance of celebrities’ interconnectivity is that it enables them to interact if they want to. Each star one becomes “friends” with has a whole Rolodex of contacts that may be useful in attaining these goals. Celebrities need to be able to interact with the most influential people in the film, music, or fashion industries; it’s important for their careers and for their ability to nurture and maintain their own celebrity status.

Talent vs. Residual: Getting into the Celebrity Network

For the outsider, the differences among celebrities seem rather academic. But not all celebrities are the same, and not all are celebrities for the same reasons.15 A basic maxim of stardom is that all celebrity is not created equal. Most of us, for example, have little interest in being Britney Spears, no matter the titanic force of her stardom, which flits across every media source from Perez Hilton to CNN to the New York Times. The musician Beyoncé, however, is far more appealing. She doesn’t get that much media attention (relatively speaking), but when she does it is generally good. She is married to hip-hop mogul and Grammy-winning musician Jay-Z and has won several awards and sold millions of albums in her own right. People around the world idolize her.

Most people would not want to be Lindsay Lohan or Pete Doherty. Despite their stardom, they are not admired. They are celebrities because they are train wrecks—fascinating to watch because they derail into crazy behavior (even if Lohan was once an adorable childhood star with great potential). Most women would rather be George Clooney’s girlfriend than Tiger Woods’s wife; they’d like to attend parties at Madonna’s house but probably wouldn’t be so keen on visiting macabre musician Marilyn Manson in his home. In other words, celebrity may be everywhere, but celebrities everywhere are not of the same caliber.

Let’s look now at the way people might get into the celebrity network in the first place. We know that celebrity isn’t just talent and media exposure, but these might at least increase your chances of becoming a celebrity. There is interplay among three qualities: (1) talent (as measured by top Billboard music singles, sports championship games, Oscars and nominations, critics’ reviews, and so forth); (2) fame (people knowing who you are, the chances of which are greatly increased by working in highly visible professions like sports or films); and (3) the celebrity residual, that collective obsession with an individual that transcends all tangible qualities or talents. Having a little more talent or a little more residual dramatically changes your network, what events you go to, and whom you have the potential to meet.

If you’re talented, how might your talent be measured? Making money for the film studio, attracting other top stars to a movie, and drawing audiences in droves seems like a fair test. The Forbes Star Currency index surveyed 157 Hollywood film executives about actors’ perceived “bankability” to their studios and ability to attract other stars to join the cast. Based on what studio execs said, Forbes ranked more then 1,400 actors. Not surprisingly, the usual suspects are at the top of the pile: Oscar winners and box office sensations like Jolie, Will Smith, Brad Pitt, Julia Roberts, Matt Damon, and Johnny Depp. The middle rung of actors produces some recognizable names of stars who are primarily TV actors with less successful film careers (Neil Patrick Harris, Jamie-Lynn Sigler, and Lara Flynn Boyle), while the bottom rung (those actors ranked 1,390 to 1,410) are virtually unknown to the general population. Gilad and I looked at these different groups individually to see if their social lives were fundamentally different from one another. We parceled out the top twenty, middle twenty, and bottom twenty ranked stars as proxies for the different stratospheres of stars.

When you look at the networks of these different groups of actors, it turns out that A-list film stars (those top twenty rated by Forbes) have absolutely different social networks from the middle-ranked B-listers and the bottom-rung C-listers. A-list status isn’t reflected only in box office receipts, awards ceremonies, and reputation among studio execs. A-listers also have a tight and densely connected social network, which allows them to remain the most elite stars on the planet. A-listers attend the most exclusive parties and awards ceremonies, and these events are naturally photographed much more than any other event that might be documented by Getty Images. There’s no surprise to this finding: If A-listers are the biggest stars, then, by extension, they are invited to the most prestigious events that then reaffirm their position. Membership in the A-list celebrity network (in which A-listers spend time only with other A-listers at the most exclusive celebrity-studded events) reinforces A-lister status and makes it harder for anyone else (B-list and below) to clamber to the top. If B-list stars are not attending (read: not invited to) A-list events, then their chance to hobnob with the top stars becomes increasingly unlikely.

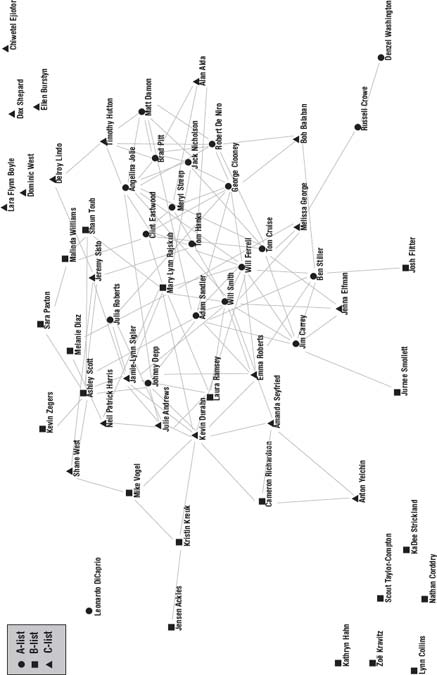

While A-listers’ friends tend to be friends with one another (an important property of a very connected network, or what social network analysts call a “clique”), the middle and bottom twenty stars have virtually no special connections with the others in their group. When removed from the entire Getty network and studied in isolation, B-listers and C-listers have hardly any unique ties to one another compared to their relationships within the network as a whole. While being a member of the celebrity network does provide access to other celebrities, only A-listers have their own exclusive inner core within the larger network of celebrities (see Figure 1). So while a B-lister is just a few contacts away from being in touch with a top star (he knows someone who knows someone who is friends with the star), A-listers essentially have no separation from other top stars. In network terms, A-listers are connected to one another by an average of 1.6 degrees of separation, and B- and C-list stars tend to be only slightly more connected to one another (2.5 and 2.22, respectively) than everyone in the entire Getty celebrity network (3.26). To be sure, they are still far more connected to one another than the average person (remember the six degrees of separation), but they are not as closely connected as those within the A-list. As a result, they do not achieve the same network benefits as those on the top rung.16

Figure 1. Social Network of A-, B-, and C-List Celebrities

Unquestionably, being a part of the A-list clique is desirable, while being a part of the other groups less so. For a film star, being at the top—getting to the Oscars and the Vanity Fair Oscar party and so on—obviously yields greater benefit to one’s star power and is an essential part of one’s career. Yes, access to those events and to A-list status itself are strongly predicated on being able to generate money for the film studio. So the more Hollywood reveres a star (his perceived “talent”), the greater his chances of penetrating the most elite celebrity networks, which of course helps increase one’s overall celebrity status. Thus, being a B-lister isn’t a stop on the way to A-list status. B-list stars are viewed as less talented than A-listers and, as such, B-list stars don’t graduate into A-list status. They stay in the middle rung and therefore don’t have the same opportunity to maximize their careers. Unless a B-lister lands a leading role that wins her a film award (and thus puts her on the invite list for coveted events) or marries an A-lister (who brings her along to those events), it is unlikely she will be given entrée into the A-list clique. A B-lister must take a quantum leap into A-list status rather than plodding along a linear path, which is why it’s often the case that once a B-lister, always a B-lister.

There are, however, other options for the less talented to become just as connected as the exclusive core of the celebrity network. Let us not forget that celebrity rests on the public and the media fixating on some people more than others (the celebrity residual). If you are not particularly talented but the world is talking about you, you can be a celebrity without having to go through the Hollywood exec vetting process. There’s no question that some stars who are talked about are talented—we’ve gone through this in the discussion of the interplay among the celebrity residual, talent, and fame. But besides being incredibly talented, the most obvious and efficient way to be at the core of the celebrity network is to get yourself photographed and written about as much as possible. These are our residual stars. Using Google media hits, we looked at the top twenty most talked about celebrities on blogs, in newspapers, and in other media outlets, and we found that those stars with lots of celebrity residual have a similar social network to Hollywood A-list actors. These most talked about celebrities tend to be connected to lots of people, attend lots of events, and have just as close connections among their friends as A-list Hollywood actors do among themselves.

Unsurprisingly, these residual stars do not have to win Oscars or generate box office receipts, but they do have to put in a huge amount of work to stay at the top. Top residual stars attend almost 80 percent more events than do A-listers. If a star does not have the talent to become a part of the elite, then the best course of action is to get out there and socialize. Socializing a lot doesn’t necessarily mean an all-residual celebrity suddenly gets invited to the Vanity Fair Oscar party. However, it does mean that an aspiring star gets access to more people and thus increases her chances of being connected to others who may help her career (take a chance on her for a film role, give her a modeling campaign, etc.). If such an opportunity presents itself and she does an excellent job at it (wins an Oscar, becomes the face of a fashion house), that just might be the push she needs to jump from B-list or all-residual to legitimate A-lister.

Celebrity status depends on the individual’s networking strategy and ability to penetrate one network versus another. Three principles make celebrity networks unique. First, celebrity reinforces itself by maintaining its collective exclusivity. By extension, celebrities must keep their network tight, so as to maintain both its exclusiveness and desirability. Second, celebrity relies on proximity and close connections to other celebrities. If Celebrity X invites you to the party, you will likely be able to connect to everyone else at the party with very minimal effort. Finally, and most important, these connections are socially and economically meaningful. In The Warhol Economy, where I studied the art, fashion, and music industries in New York, I found that a preponderance of those in the creative industries moved to New York primarily for networking purposes. They realized that establishing friendships and connections with high-profile individuals in their industries was essential to their success. Going to parties, gallery openings, and runway shows were the channels to do this. “The social life in New York is very work oriented,” Diane von Furstenberg told me. “There is a support system that weaves and creates the social.” Fashion designer Daniel Jackson explained, “Informal social networks are probably the most powerful driver, pretty much everyone we work with we have a personal relationship with.”17 By virtue of penetrating the celebrity network you are connected to tons of people who can further your career and status.

The Celebrity Network in Action:

The Social Network of Anna Wintour

For anyone who cares about fashion, the aggressively thin woman with the pageboy bob and enormous dark sunglasses has defined the industry since 1988. With her British accent and pithy retorts, Anna Wintour, editor of American Vogue for the last two decades, has made and broken careers with the mere nod of her head. Fashion insiders and reviewers read Wintour’s attendance at runway shows like tea leaves. As a public figure, she is known for, among other things, making Zac Posen the darling of Barneys, getting John Galliano his job as creative director of Christian Dior, and being a perennial favorite on PETA’s most-hated list for her casual fur wearing. She rarely gives an interview, and is in bed by ten fifteen every night.18 She is the host of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s annual Costume Institute gala, otherwise known as “the Party of the Year,” which is possibly the most concentrated grouping of celebrities in the world.

In 2006, Anna Wintour (also known as “Nuclear Wintour”) became a household name. The Devil Wears Prada, the novel and blockbuster movie about Miranda Priestly, the ice queen of a top-tier fashion magazine, changed Wintour’s profile from relative celebrity for fashion aficionados to world-renowned celebrity likely to be recognized by suburban housewives as well as cargo shorts–wearing engineers like my brother. The book, written by former Wintour assistant Lauren Weisberger, was largely received as the roman à clef of Wintour’s reign at Vogue. “Besides giving Weisberger her fifteen minutes of fame,” Wintour biographer Jerry Oppenheimer remarked, “Anna [was] squarely in the mainstream celebrity pantheon…Anna was now known and talked about over Big Macs and fries…in Davenport and Dubuque.”19 In all the flurry over the book, Wintour merely commented, “I am looking forward to reading [it].” She personally selects the attire for A-list stars for the Costume Institute gala and once refused to put Oprah Winfrey on the cover of Vogue unless she lost weight and Hillary Clinton unless she stopped wearing navy blue pantsuits. Wintour’s power in the fashion arena is indisputable. She remains the most influential fashion icon in the world and has access to every celebrity.20

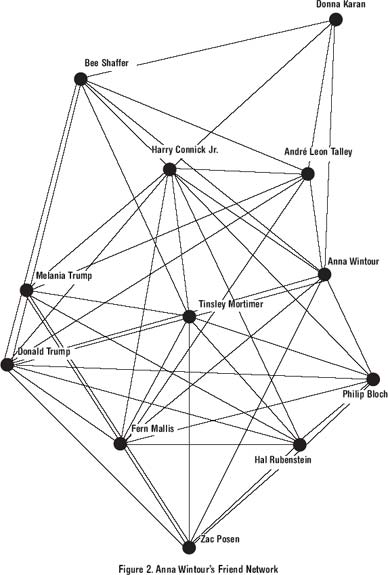

Wintour’s social life effectively demonstrates the basic principles of celebrity social networks and the various possibilities for attaining celebrity. Once penetrated, her network, like all celebrity networks, enables a person to get to particular people. Between March 2006 and February 2007, Wintour attended sixty-nine events around the world at which she was photographed by Getty. That’s actually not a lot compared to our favorite all-residual celebrity, Paris Hilton (who went to 50 percent more events in the same period). Wintour’s social life can be categorized as a “fully connected network” or a “clique,” which means that all the people who attend events that Wintour attends are likely to attend them together. The members of the network run in a pack, so to speak, even if the pack is made up of separate limos. Figure 2 gives a sense of some of the people in Wintour’s network.

Once a person has penetrated Wintour’s exclusive circle, there are other networks worth linking into, depending on one’s goal. If he or she is at the same party as Wintour, there is much greater potential to access her (and maybe strike up a conversation that leads to friendship). An aspiring fashion designer ought to try to establish a rapport with Wintour that might benefit her career. The rise of fashion houses Proenza Schouler, Rodarte, and Thakoon have been credited to the designers establishing a bond with Wintour.21 People who go to the same events as Wintour are just one degree of separation away from her, so such a goal is pretty realistic.

If a celebrity or aspiring celebrity simply wants more celebrity friends, his or her best bet is to befriend those in Wintour’s circle who are most connected to other celebrities attending these events, such as second in line at Vogue, André Leon Talley, rap star Kanye West, or socialite Tinsley Mortimer. These people tend to get photographed with lots of different people. In social-networking terms, these individuals are called “hubs.” But just because one has contact with lots of people does not necessarily mean these connections are meaningful for getting a job or an invite to a coveted event. Those who want to get invited to parties and attain a wider net of contacts outside of Wintour’s immediate circle (maxing out the “preferential attachment” property of celebrity networks) ought to become friends with those who attend lots of diverse events (not just the ones Wintour attends). Social network analysts call these people “boundary spanners” because they tend to be a part of different social groups and can act as a bridge between diverse members of the network.22 Within Wintour’s circle, examples of boundary spanners are Donald and Melania Trump and burlesque goddess Dita Von Teese. The Trumps are a multi-industry power couple: Donald is a real estate mogul and TV personality and Melania is a former model. Not to mention, they are so powerful and are such celebrities that they are invited to major events simply because of who they are. Von Teese is a model, cult personality, and fashion muse who, like the Trumps, bridges many different industries and social groups.

If a celebrity’s basic goal is simply to increase his or her own star wattage, not so much become friends with those in Wintour’s network, then the essential connections are with those celebrities who get photographed the most at Wintour events. Harkening back to Boorstin’s point that celebrities are celebrities because they spend time and get photographed with one another, an aspiring star must make contact with the biggest stars present at the party. In Wintour’s world, these individuals have historically been Katie Holmes, Sienna Miller, and Victoria “Posh” Beckham. But because celebrity status changes at the drop of a dime, the most photographed do so as well.

A Typology of Celebrity

Not all paths to celebrity are equal and, as Wintour’s friend network demonstrates, not all celebrity networks offer the same result. Depending on what one wants from celebrity (whether making celebrity friends, becoming a celebrity, or getting access to a particular person), he has to decide which type of celebrity link and network will help him attain his goal. Part of the differences between Paris Hilton’s and Anna Wintour’s celebrity can be explained by the ratio of the three intermingling qualities a star possesses: talent, fame, and the celebrity residual. The distribution of these attributes in a person influences the type of star he or she becomes. Let’s take a look at a few examples.

Some individuals strike the ultimate balance between talent and residual. Stars with consistent talent-based careers like Angelina Jolie or British supermodel Kate Moss perpetuate their elite status by, first, not attending many events and, second, picking those events that reinforce their image. Jolie goes to charity events, a few high-end cultural events (like the art opening for British street artist Banksy), and an award ceremony or two. Moss tends strictly to go to very cool fashionrelated events (including, of course, her own Topshop brand launch party). Both Jolie and Moss can afford to be selective. Jolie can easily land another good film role, and Moss is plastered across every billboard or magazine worth a cent. In addition to holding tremendous star power, both are well-known talents in their fields, so they are constantly backing up their celebrity with substance. They rely less on being seen out and about for their celebrity status, because they have a talent that reminds the world they exist.

Additionally, because they have talent, they are able to be more exclusive, which of course increases their prestige. The words “Oh, her again” never emerge out of any paparazzo’s mouth when one of these ladies shows up. The all-residual celebrities, however, must plug away at the social scene. They don’t have a major fashion advertising campaign splashed on every billboard; they don’t have a magazine to edit or a major blockbuster to star in. Since most residual stars do not have a consistent talent with which to broadcast their existence, they need public exposure in order to capture the public’s interest and, consequently, to maintain their stardom.

Paris Hilton is nothing if not for the parties she attends. Of every celebrity Gilad and I investigated, she is far and away the most socially promiscuous. She has fewer degrees of separation from other celebrities. Lindsay Lohan may have had promise as a childhood actress, but in recent years she has become all-residual and, like Paris, shows up at any party worth its salt, affording her access to many more people. Most big stars—Tom Cruise, hip-hop musician and actress Queen Latifah, and musician Justin Timberlake—go to twenty or so high-profile events a year that the media covers in great depth and the public has great interest in (the Oscars, major movie premieres, and so forth). They are not, however, attending multiple PlayStation or cell phone launches or clothing boutique openings like all-residual celebrities.

Our look at celebrity networks also indicates that at some point there are diminishing returns to social promiscuity. Despite Paris Hilton’s relentless social life, she does not have significantly more access to other celebrities than the more reclusive celebrity does. All of her frolicking makes her only a mere one-third degree of separation closer to others than everyone else, and on average she has the potential to meet a much smaller group of people at a given social event than does any other celebrity. The latter result is explained by the fact that in any exclusive network there are a finite number of people to meet. With each event that Paris attends, she reduces the chances of meeting new people within the network. More generally, one might argue that if Paris did not do all the socializing she does, she would not be nearly the celebrity she has become. Paris’s social promiscuity gives her only a marginal leg up, but being just that much more connected is what makes Paris, well, Paris. Meeting just that one extra contact who provides an opportunity can be a game changer for an all-residual star. But it’s clear that talent is a far easier (and more certain) way to attain elite status within the celebrity network. The thing going for Paris is that, despite demonstrating no discernible talent, she somehow got into the network in the first place. And she’s been exploiting it ever since.

Networking does matter. And celebrities, as their social lives and networks demonstrate, are fundamentally different from you and me. More than talent or even misbehaving and getting written about, their ability to perpetuate their celebrity status is dependent on their ability to remain a part of the celebrity network, which is the way their antics get photographed and written about in the first place and ultimately how we remain fascinated with their lives. Perhaps most important, however, the study of celebrities’ social lives tells us that strategic networking is the most critical aspect of attaining the type of stardom one desires.