6

Whatever You Do, Don’t Go to Vegas: The Geography of Stardom

When I would fly into Los Angeles at night, the city was like a twinkling wonderland. It also held an answer to some fable or dream I was after. I began using it as background, and then I realized how important backgrounds really are.

—Ed Ruscha

Cory Kennedy became a star at sixteen years old due to the Cobra Snake. Cobra Snake, also known as Mark Hunter, was a photographer documenting the LA party scene. A scruffy young guy (twenty-one when he met Kennedy), Hunter was a bit of a legend for his access to the best of highbrow and low-brow LA nightlife. One night he would be at graffiti star Shepard Fairey’s DJ show at La Cita in downtown LA, and another he’d be taking pictures of a fashion runway show. All of these photos were put up on his site, Polaroid Scene, which later became the Cobra Snake.

One night in the summer of 2005, at a music show at El Rey Theatre on Wilshire Boulevard, Hunter met Kennedy, a meeting that would be the watershed moment in Kennedy’s life as she knew it. About six months later, Kennedy started interning for Hunter and joining him at all the celebrity events he photographed. But two other things happened: Hunter and Kennedy started dating, and Hunter started posting pictures of Kennedy attending all those events they photographed together. Hunter then noticed something very interesting: When he posted those pictures of Kennedy, his web traffic spiked dramatically. So, naturally, he posted more pictures of her. By the following summer, Kennedy was on the cover of übercool fashion magazine NYLON and featured in newspaper articles and profiles in the New York Times and Los Angeles Times and in various other mainstream media. She appeared in a music video rocking out to Good Charlotte’s “Keep Your Hands Off My Girl,” which became one of the most widely viewed Internet videos of all time.1 Kennedy signed on as the face of makeup company Urban Decay and she became friends with all the young starlets from Paris to Lindsay Lohan to Samantha Ronson. She became one of the most popular girls on MySpace (over 20,000 friends) and developed an active Twitter following (some 23,000 followers as I write this).

Along the way, Hunter and Kennedy broke up. These days she spends her time with her new rock star boyfriend (at the time this book was written, she was dating Jamie Reynolds of the indie Brit band Klaxons) and pals around with British socialite celebrity Peaches Geldof. A look at her tweets tells a story of a girl living on a plane traveling from glamorous city to glamorous city to runway shows and parties with the London–LA–New York jet set. Her blog features pictures of the details of her life, including a montage of photos from her attendance at an Easter party thrown by Paris Hilton. (Paris is wearing a faintly ridiculous sequined hot pink bunny outfit, which doesn’t really strike the traditional tone of the holiday, but she looks fabulous nonetheless.) Kennedy’s MySpace profile features dozens of videos of the various interviews she has given at the Marc Jacobs runway shows, at Betsy Johnson’s runway show, at a NYLON party, and the list goes on.

In one of these short videos, an overly eager interviewer shoves a microphone in Kennedy’s face and asks, “How do you feel about being the ‘it’ model of the world right now?” Kennedy’s response was not noteworthy. While Paris, despite seeming vapid, is able to entertain with her witty one-liners and the fact that she seems to revel in her gloriously absurd existence, Kennedy’s verbal skills are not scintillating. Most of her interviews involve her muttering uninteresting non sequiturs that never quite form a sentence. In that respect, some might argue Cory Kennedy is not actually star material. As one Gawker commentator put it: “Go to school, honey. Go to prom. Assemble a vocabulary.” Gawker itself has called Kennedy a variety of cruel names, from “homeless-looking hipster” to “teen fabutard” to “Internetard” to being a part of a coterie of “notable idiots.”

Okay, she can’t give a good interview, and okay, her insouciance comes with too much effort, but that hasn’t stopped Kennedy from maintaining her high-profile existence and hobnobbing with the global in crowd. As long as Kennedy keeps her mouth closed, she certainly looks like any other celebrity. She has nice hair, always tangled in her signature style. She has porcelain skin. She has big, wide eyes and long eyelashes. She dresses somewhat quirkily in the grungy chic that supermodels on their days off cultivate perfectly. Kennedy is as good-looking and stylish as any star, but more important, photographs document Kennedy hanging out front and center with celebrities, including her rock star boyfriend.

Kennedy’s star power is fundamentally a function of having physically located herself within the geography of celebrity, or, in common parlance, of being in the right place at the right time. Think of it like this: Pretty people are everywhere. Being a nice dresser doesn’t get you on the cover of a fashion magazine. Every actor-cum-waitress can tell you that occupation isn’t the sure path either. When we’re talking about mainstream celebrity, people become stars by going through the networks and industries in Los Angeles, New York, London, and the other global celebrity hubs before making it around the world. Particular places matter because of the instant nature of current celebrity; everyone who is a part of creating celebrity needs to be in the same tightly constructed geography at the same time and on a fairly consistent basis in order to maintain and document celebrity. Cory Kennedy’s celebrity depends on the people and conduits that make her a star.

These mediators, whether publicists, photographers, or journalists, are located primarily in Los Angeles, New York, and London. As Brandy Navarre, one of the cofounders of X17, the largest LA-based paparazzi site, explained to me, celebrities exist because they are written about and photographed consistently. “[X17 is] constructing a story every day. Everyone buys People magazine, everyone buys US Weekly. They have to be a part of this, in front of our lenses, in order to be a celebrity.” Almost four hundred thousand unique visitors from Kansas City to Tokyo may troll X17’s website every day for celebrity images, but the lenses generating those photos are in LA.

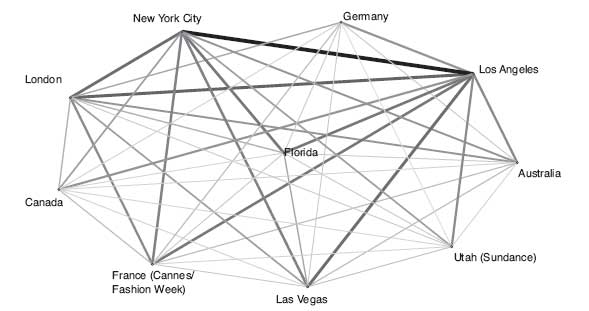

Take note of this statistic: Of the six hundred thousand–plus photos taken in one year of entertainment and celebrity events by Getty Images, 80 percent are taken in three locales: New York, London, and Los Angeles. Of the 187 places around the world represented in the photo database, London, New York, and Los Angeles are not only the most photographed locales but also the most connected to one another. When my colleague Gilad Ravid and I looked at which places stars attended events we found that they tended to move around among just these three cities. During their annual star-studded events, Cannes, Miami (during Art Basel), and Park City (during the Sundance Film Festival) act as specialized, temporary celebrity centers (see Figure 3). Las Vegas lures some stars off their normal stomping grounds but mainly for parties rather than prestigious industry events. But besides a select few cities no other place is a real player in the geography of stardom. This makes sense: Getty is the largest photographic agency in the world and sells its pictures to big and small media outlets everywhere. It is no surprise that the people who are photographed by Getty are individuals we are aware of, while those who don’t get photographed are people we are not. Sure enough, a little over six months after the Cobra Snake started documenting her, Cory Kennedy started showing up in Getty Images photographs taken at LA Fashion Week.

Figure 3. The Geography of Stardom Network

You can’t become a global, mainstream celebrity if you don’t get yourself to a place where the paparazzi and media outlets have set up shop (and the paparazzi are where the stars are), whether that’s in the big global cities or the specialized, temporary celebrity hubs. “If you’re not in the thirty-mile zone, then you’ve kind of opted out,” one celebrity journalist explained. “LA, New York, London—that’s where you go to show the flag. For the life of me, I can see no other reason to go to Hyde [an LA nightclub].”2 Hence the circular relationship between the media and celebrity, which calls to mind the response of the famous bank robber Willie Sutton when asked why he robbed banks: “Because that’s where the money is.”

However, one needs more than being in Los Angeles to become a movie star or in London to be considered part of the global jet-setting elite. If celebrity rests significantly on the photo, then being in front of the flashbulb at the right instant is what counts. Living in New York and Los Angeles, while upping your chances of being “discovered,” isn’t the same as partying in the same clubs at the same time as Paris Hilton. Paris’s presence guarantees a nonzero chance that someone with a camera and a magazine or website will be there taking pictures. Cory Kennedy, trotting along with Hunter to the celebrity events he photographed and then taking her place in front of the camera, was exactly where she needed to be to become a star.

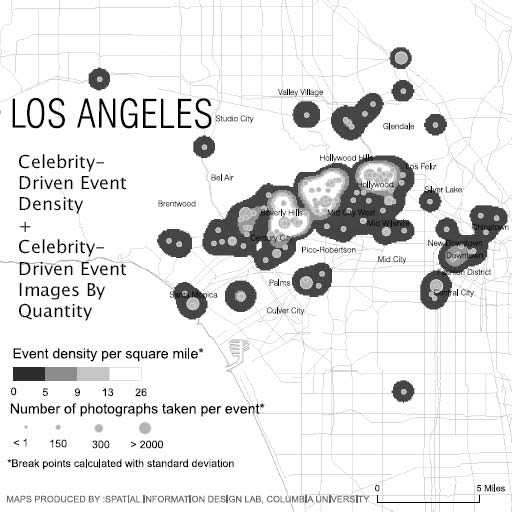

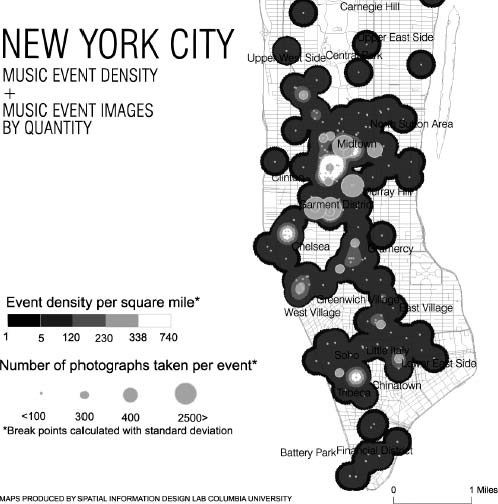

In order to understand precisely where these photographs of stars are taken, my Columbia University colleague Sarah Williams and I studied all of Getty’s photos of celebrity events in Los Angeles and New York. We had a few questions: Did all the celebrity industries (e.g., fashion, art, music, film) throw parties in the same places? Were celebrities all hanging out in the same places over and over, or was it completely random? If we observed a concentration of celebrity-studded events in the same place, was it merely a coincidence or had we stumbled across a statistical pattern that documented the physical location where people became stars? Using GIS (geographic information system),3 which merges cartographic information with database information, we were able to take the data from the photographs’ captions (who is in the photo, where it was taken, what event) and attach addresses and longitude and latitude tags (also called “geo-codes”) to each of the three hundred thousand total photographs taken in the two cities over a one-year period. We then used those geo-codes to map where each photograph was taken. After mapping the photographs, we analyzed the images and looked for links among art, fashion, music, film, and entertainment events.

Our analysis produced robust statistical findings. First, there are a finite number of places where celebrities are photographed. Second, there is nothing random about where these photos are taken; our analysis demonstrated that there is a strong statistical pattern for where celebrity events happen. Further, no one in the celebrity world is acting on his or her own: All the celebrity moments in fashion, film, music, and art occur in the same places, and these places are piled up against one another. In other words, it’s not an accident that all the stars are partying, walking down red carpets, or smiling for the camera in the same venues and on the same streets. In Los Angeles, for example, all of Getty’s celebrity photographs occur within a very narrow spine along Sunset and Hollywood boulevards between Vine Street and the Beverly Hills Hotel. That’s about five miles east to west and a quarter mile north to south (see Figure 4 and Appendix D).

When we look even closer at the photographs, there are literally only four neighborhoods where celebrity events are regularly photographed: Hollywood, Beverly Hills, West Hollywood, and Century City.4 This geography of stardom does not include the informal, casual shots that photographers for TMZ, X17, US Weekly, or Big Pictures take of some celebrity getting a pedicure (Getty covers the “events that matter,” so to speak). Not only are these latter photos shot in roughly the same parts of town as Getty’s, but also their main purpose is to fill in the narrative of daily life of an already established celebrity. Grabbing coffee at Starbucks in Hollywood is not a way to become a star at the outset, but being on the red carpet at the Oscars, at a best-selling author’s book party, or at the TriBeCa Film Festival, or emerging from the Fashion Week tents at Bryant Park just might be (which means your pedicures and coffee runs to Starbucks may eventually also get photographed by X17 and featured in US Weekly).

Figure 4. Los Angeles Celebrity-Driven Events

Plugging into your respective star geography counts. In New York, if you’re involved in the music industry and you’re not playing at Lincoln Center or Madison Square Garden, your best bet is to be at the nightclubs in Chelsea (see Figure 5). These are the locations that the media covers the most for music-related celebrity-studded events. Luckily, some of these hubs are centers for all types of celebrity, from fashion to art to music and film. For example, the stretch between Hollywood and Beverly Hills hosts almost all of the important events for the entertainment industries in Los Angeles. As tacky as Times Square may be to New Yorkers, hanging out there will dramatically increase your chance of running into celebrities from music or fashion walking into big events in its environs.

Figure 5. New York City Music Events

Similarly, there are “places within places” that drive different types of celebrity. In other words, different kinds of people interested in cultivating particular types of star profiles appear at totally different venues and events. Consider the vast chasm between MTV’s Total Request Live (TRL) in Times Square and some hot and exclusive nightclub in Manhattan’s hip Lower East Side. Certain celebrities maintain their mystique and cool status by going to “in-the-know” restricted places on the Lower East Side that would be much less appealing to the mainstream celebrity seeking avenues to maximize his or her public recognition. These smaller nodes within the city operate differently from each other in the cultivation of celebrity and are accessed through totally different strategies. TRL, one of MTV’s most popular daily programs, features a guest star at every show. The program is far more constructed and controlled and requires the “right contacts”—major publicists and agents—and the “right look” that appeals to a mass audience.

Yet, despite all the legwork involved, TRL is a more democratic and less exclusive method for distributing information about celebrities. The Lower East Side club may not require a six-month lead time of begging publicists to get their star on the roster, but only the coolest clique of stars and their followers are able to get their foot in the door. In this respect, the LES club affirms the truly elite network of celebrity. Or consider the different types of celebrity—politicians, socialites, the old guard, and the ephemeral—all of which tend to have their own venues to see and be seen. New York’s legendary restaurants Michael’s and the Four Seasons, while infiltrated by the starlets, are generally the headquarters for the old guard—there is gravitas to these institutions, and the people who frequent them reflect this. The Mayflower is Washington’s celebrity institution for politicians, the very hotel where shamed New York governor Eliot Spitzer turned from politician to political celebrity when he got busted for arranging trysts with a prostitute. Contrast these institutions with the flurry of trendy nightclubs, most so short-lived that naming them is gratuitous, as their significance (and chances of remaining open) changes almost monthly. While they are extremely exclusive, they are also interchangeable and occupy temporary positions of stardom, much like their patrons.

Equally, on a larger scale, not all geographies of celebrity are the same. Los Angeles, New York, London—they are different. From the media to the social outings where photos are taken to the types of celebrities these towns produce and attract, the very constitution of celebrity in each of these locales is unique. “The West Coast has been for a long time where a certain kind of fashion that young people want is rooted as well as the proliferation of the paparazzi and the weather,” Hollywood PR stalwart Elliot Mintz explained. “In New York City, in the cold, dreary weather, you can’t wear those outfits. In Los Angeles, you can. So with all due respect to a picture of Martin Scorsese, in California, all the girls have suntans.” This is all by way of saying that being in the right celebrity hub—just like being friends with the right celebrity—is what enables one to cultivate a particular kind of stardom.5

A place or an event becomes a celebrity hub because celebrities bother to show up there in the first place. Tom Cruise would likely attend the Academy Awards ceremony, which happens to be in Los Angeles, and serious actors make it a point to attend the Cannes Film Festival, so Cannes and Los Angeles become hot spots. Simply put, the events that celebrities go to are hosted in particular places. Stars are then compelled to go to those places, thus creating a system that creates and reinforces itself—what economists call “endogeneity,” whereby each variable in the system predicts the others’ behavior.6 But there is another way to look at these travel choices: Tom Cruise becomes a highly respected star partially because he goes to events in those particular places versus attending events in other locales. Consider Cruise’s other options: Las Vegas; South Beach, Florida; Ibiza. These are also celebrity hubs. But Tom Cruise is not one of the celebrities who create the reputations of these latter places. Just as on a smaller scale, Total Request Live attracts very different stars from the club on the Lower East Side, celebrity geographies are different because the people who frequent them are different. By extension, visiting one city over another may explain how celebrity types emerge. Thus, in order to be a particular type of celebrity, an aspiring star ought to be mimicking a particular travel pattern. As with celebrity networks, there is a strategy buried in a star’s geographical choices. Understanding the movements of stars from place to place, where they go and whom they spend time with, tells us a lot about how some people become stars and how one celebrity has a different character from another’s.

When my colleague Gilad Ravid and I looked at those six hundred thousand Getty Images photos taken of celebrities around the world in one year, we found that stars exhibit vastly different types of traveling patterns going in and out of celebrity hubs.7 We know intuitively that stars are fundamentally different from one another. Some launch themselves by being talented and respected by their industry and then are splashed across the tabloids; others are born in the gossip columns and remain there throughout their celebrity lives. Talent is not the same as being “talked about.” But how do these stars behave differently? We know that their social networks are different, but do they also hang out in different cities and at different events?

To get at talent, Gilad and I used Forbes’s Star Currency, a measure of a star’s perceived bankability. Based on a survey of top Hollywood studio executives, Forbes allocated each star a composite score from 0 to 10, with number one–ranked Will Smith getting a 10 and Johnny Depp and George Clooney both getting above a 9.8, compared to Paris Hilton, who got a score of 3.21. We compared the talent scores with subjects of gossip, which we measured by searching Google for media and blog mentions. In this area, Paris Hilton is the fourth-ranked star in terms of sheer volume of media mentions (Michael Jackson, Britney Spears, and Madonna ranked first, second, and third). We then studied the A-list, which we defined as the top twenty Star Currency celebrities, to see if they have different types of traveling patterns from everyone else. From the very talented celebrities (those with greater Star Currency), to those residuals who are documented endlessly on blogs and stack up volumes of media mentions, right down to the C-list (those ranked 1,390–1,410 on Star Currency), we found that discrete and unique traveling patterns to and from the celebrity hubs emerge. Going to the right places at the right time is critical in determining celebrity status. Quite simply, if an aspiring celebrity wants to be an A-lister, he or she needs to be making the same global pit stops as other A-listers.

A-list celebrities and residuals tend to make a couple of similar key decisions. First, and unsurprisingly, all celebrities show up in Los Angeles at least some of the time, whether they are residual or the top scorers in Star Currency. Celebrities with lots of Star Currency (read: talent) must show up in Los Angeles like everyone else. Other than making a few cameos, however, top stars keep a relatively low profile in Los Angeles compared to other types of stars (no boutique openings or random parties for Tom Cruise, for example). The rest of the time they are flitting off to other venues for big events and parties, particularly New York and London. Yet visiting these places alone is not a sufficient traveling schedule in itself. Despite the fact that more photos are taken in the Big Three than anywhere else, top stars are traveling to lots of other places, such as Tokyo, Paris, and Germany. Thus we get to a critical juncture: The top talent-driven stars rarely appear at events that do not have a link to the industry, a charity, or a cause they are championing, whereas residuals can be found at virtually any kind of event where photographers are present.

There is a global demand for the top stars at the most prestigious events, which is why they are seen around the world. A-listers keep moving around from place to place more than C-listers and notably more than most other kinds of celebrities. Half of the top twenty ranked in Star Currency are in the top hundred of most-traveled celebrities, which means they are on flights to events around the world more than other celebrities. Because they are so elite, these stars show up primarily at key events like the Academy Awards, the Cannes Film Festival, or London and New York Fashion Week. Top talent-driven stars do not necessarily attend tons of events in Los Angeles. Angelina Jolie showed up at events in LA just five times in one year. Despite being a Hollywood icon, Jack Nicholson was photographed only eleven separate times in Los Angeles. Beyoncé, one of the biggest stars in the world, made just ten appearances in Los Angeles in the same year. Compare these figures to residual stars like Paris Hilton and Lindsay Lohan, who make multiple appearances in LA events, forty-four and twenty-two, respectively. In other words, A-list stars tend to travel far and wide but otherwise scarcely be seen. This makes sense: A-listers are more likely to be at events around the world because of their global celebrity status. B- and C-listers, in contrast, show up disproportionately in Los Angeles. Many of them live in LA (it is, after all, the TV and film capital of the world), and most of the small-scale celebrity events associated with boutique or nightclub openings that a B- and C-lister can get into are located there too.

After studying star travel patterns, Gilad and I wanted to tease out whether showing up in one place over another was positively or negatively associated with a celebrity’s Star Currency or media mentions. We looked at where all six hundred thousand photos were taken and ran statistical analyses to study the correlations between where stars go and their rank on Star Currency (talent) and media mentions (a measure of residual).8 We found that showing up in Los Angeles is not associated with an increase in a celebrity’s Star Currency, whereas traveling to exotic locales like Japan or Germany is strongly predictive of increases in star talent-driven power. This can be explained by the fact that Los Angeles is a destination for all stars and therefore is not a unique travel choice. If every other star or aspiring star is passing through Los Angeles, one has to do something different to set oneself apart from the crowd. For example, attending events in Australia seems to be a good move for talent stars and residuals: going to one event is associated with an increase of almost 2,200 media mentions and 0.4 on one’s Star Currency score. Going to an event in London correlates with increases in one’s Star Currency score by almost 0.5. A New York event is also (though less) important, associated with an increased score of 0.212. These may seem like small increases, but when we’re dealing with a range from 0 to 10, an extra half point is a 5 percent increase in Star Currency, no small feat for attending just one extra event in London. And the stars being photographed in London back up these stats: The celebrities most photographed in Great Britain (removing Queen Elizabeth and Prince Charles from our analysis, which, to be fair, slightly skews our results) are Beyoncé, Helen Mirren, and Johnny Depp. All three of these stars are genuine A-listers, and not just because of their celebrity; they are talented and genuinely admired by their public.

For residual celebrities, showing up in London is just as important: One extra visit increases one’s coverage on blogs and media by almost 1,250 mentions. The “London effect” isn’t surprising. First, Great Britain’s influence can partially be explained by the fact that there are fewer events in London than in LA, which means those events are rare and implicitly more exclusive. Second, despite being an island of only sixty million people, Britain is one of the most important celebrity hubs in the world. Media around the globe covers the big London celebrity and entertainment scene. But perhaps most critically, unlike the United States with its 1,408 daily newspapers and endless TV channels, Britain has a far more concentrated national media. Americans have many more niche and regional media markets: Of those 1,408 dailies, only 395 have more than fifty thousand subscribers.9 Contrast this diluted audience with Great Britain: In England, there are 15 major dailies (including the tabloids) and 63 regional daily newspapers. Scotland has 12 major dailies and 11 regional daily newspapers. Further, regardless of their political affiliation, almost all Brits get a significant proportion of their news from one centralized source: the BBC. If the BBC reports on an event, you can bet most Brits have seen the headline online or on TV or listened to it on their way to work. If you can make it into London’s media montage, then you’ve immediately landed a very large and focused audience.

Nonetheless, if you’re an A-lister (or an aspiring one), there is such a thing as too much of a good thing. While showing face in the top celebrity hubs and a few far-flung cities is important, repeatedly showing up anywhere tends to at best have no influence and sometimes is even negatively associated with Star Currency rank. Being photographed in London for more than one event in a row reduces Star Currency by 0.1. Paradoxically, sticking around particular cities is predictive of an increase in one’s residual. Spending more time in Los Angeles and New York is associated with increased Google media mentions and blog volume by almost 200. Further, showing up at just one event in Los Angeles is associated with increased media volume of almost 1,100 mentions, even if it has no association with talent. In other words, it does not behoove Paris to show up in Los Angeles at forty-four separate events if she wants to transcend her famous-for-being-famous status, though it will keep her in the camera’s focus. The beneficial results to the residuals can be explained by the fact that not only is Los Angeles a huge media hub, but if the A-listers aren’t bothering to show up, the media will take photos of whoever is hanging around. Additionally, photographers spend most of their time in Los Angeles (and to a certain extent New York) and so end up capturing a lot of events that aren’t necessarily exclusive. But that’s no ticket to becoming a legitimate A-lister. While showing up in Los Angeles is a necessary part of being a star, it has a neutral impact on Star Currency score. A-listers stay on the move. Being busy, important, or in demand around the world, or at least pretending to be, is strongly associated with the top stars.

Not everyone can be as gorgeous and talented as Beyoncé or as much of a box office draw as Johnny Depp. As we know already, there are many different types of celebrities. Residual celebrities have their own travel patterns that keep their type of celebrity alive. Never underestimate Paris Hilton’s prowess of using her round-the-world travels to max out her all-residual status. Paris recognizes that her celebrity rests on being in the camera’s flash as much as possible, which means she needs to be in a lot of places and, simultaneously, in the same place (LA) so that people can constantly record her life as it unfolds. Not having any great talents to fall back on, she can’t rely on turning up at the significant events only to disappear from the limelight on other occasions, the way Jolie, Nicholson, and Beyoncé are able to do. So Paris’s strategy has to be slightly different. She shows up at the events that count and makes sure to be around more generally, which is why Getty gets a shot of her entering an award ceremony or a restaurant opening, and paparazzi agency TMZ catches her leaving a nightclub on a random Wednesday night.

Paris is also on a plane all the time—in fact, significantly more than anyone else. In our study of celebrities’ traveling patterns between events, we found that Paris had to get on a plane at least fifty-three times in order to make all the events she went to in one year. And because celebrity is also about generating a collective interest in one’s daily life (particularly when there is no talent to push), Paris sticking around LA for extended periods of time is an important way for her to feed tabloid, blog, and general media interest in her general existence. Celebrities like Paris are in a tough position: Getting photographed at various events in the same place definitely bumps up her celebrity residual, but remaining local simultaneously takes away from her Star Currency and thus her ability to be perceived as a talent-driven celebrity. In terms of stardom, there’s a real decision to be made: Should Paris toil away at her acting and risk being forgotten, or does she just keep reminding us she exists and remain the ultimate all-residual celebrity?

Paris attends two and a half times as many events around the world as the busiest A-lister (Tom Cruise) and has to travel more to make it to the ninety-five events she appears at in one year. Residual with a touch of B-list star Carmen Electra went to fifty-two events in one year and was photographed 1,149 times by Getty Images. Compare these two celebrities to inveterate A-lister Cruise, who showed up at just thirty-nine events and was photographed 1,446 times, and the seemingly reclusive Angelina Jolie and George Clooney, who attended just twenty-three and twenty-two events, respectively, in the same year. Paris has to maintain her hectic schedule in order to maintain her stardom: While Angelina Jolie attended one Getty-photographed event in London that year, she was photographed 100 times there. When Tom Cruise attended one event in London, his U.K. Mission: Impossible film premiere, he was photographed 111 times. Paris, on the other hand, showed up at ten London events and was photographed 173 times. Her ratio of events to coverage is much smaller than Jolie’s or Cruise’s (17.3 versus 100 and 111), who are in such demand they barely need to show up at anything to generate photographers’ flashes. Underneath her seemingly chaotic schedule, Paris’s travel patterns reflect a need to remain in the public eye to perpetuate her celebrity.

There is one rule that both A-list and residual celebrities should follow: Don’t go to Vegas. Going to an event in Las Vegas not only does not influence your Star Currency, even worse, sticking around has a negative influence. In the year we studied, only two top Star Currency celebrities had been photographed at events in Vegas: Ben Stiller and Adam Sandler. In statistical terms, sticking around Vegas for an extended period is associated with a celebrity’s Star Currency score decreasing by almost one-third of a point. Residuals do not follow these rules religiously, even though their media presence is not positively associated with Las Vegas events either. Paris Hilton and Carmen Electra, two of the most photographed residual stars, have been photographed in Vegas numerous times. Outside of Los Angeles and New York, Vegas is these ladies’ most documented location. One might argue that spending time in Vegas hasn’t hurt Paris, but remember she’s counteracting this potentially destructive move with her endless globetrotting. For the residual celebrity, staying in Vegas (as opposed to jetting in and out for one night) is an even worse idea, as it decreases Google media mention volume by almost two thousand mentions. This finding isn’t surprising: Las Vegas isn’t celebrity central unless Paris is hosting a night at a big club or some celebrity is having a birthday party. If you’re in Las Vegas after the party is over and the media long gone, it means you’re not in front of a camera or at an important event somewhere else.

Of course, all of these statistics can be explained by the fact that different kinds of celebrities have to behave in different ways. Part of a talent-driven A-lister’s strategy is to keep away from the media. If you’re an A-lister, you are already in the sights and minds of the powers that be in Hollywood, New York, and London. You’ve already gotten your invite to the Vanity Fair Oscar party and Anna Wintour’s Costume Institute gala. Vogue wants you on the cover because you’re beautiful and you’ve won an Academy Award. In other words, like your networks, you show up in the hubs when you attain maximum impact—and that’s it. Your celebrity is perpetuated simply because you are always in the spotlight and on the public’s mind for your latest top-ten single or blockbuster movie. We already care about you. If you’re an A-lister, being around too much, creating a persona independent of the image the public has of you, can have a negative impact on your career. A Hollywood film development director explained to me that sometimes an actress’s celebrity can overshadow her ability to truly become the character in a film. As she put it, “As soon as Lindsay Lohan went from being the cute, seemingly talented actress on Freaky Friday to becoming a tabloid [sensation], she dropped off everyone’s list in terms of the big producers. If you seem like such a big hot mess in the tabloids, people really don’t want to be associated with that.”

Even Angelina Jolie, despite seeming to want to live a private life, runs the risk of being overexposed simply because the world is obsessed with her. Manohla Dargis, the New York Times film critic, described this danger with regard to Jolie’s performance in A Mighty Heart. “Like all big movie stars, she can’t disappear into her role for long,” Dargis wrote. “Rather, she bobs to the surface of our consciousness, recedes, bobs to the surface, recedes. Her celebrity bequeaths the movie its capital ‘I’ importance.” For talented stars whose celebrity is a side effect of their high profile in film, music, fashion, or politics, maintenance of their talent must remain the priority; their celebrity is self-perpetuating as a result of already being in demand.

If you haven’t won a major film award or costarred next to Robert De Niro, however, and you want stardom, going out only when the red carpet is particularly plush isn’t necessarily a viable option. The whole essence of the celebrity residual is reminding the world of one’s existence. The best way to achieve this goal is by maintaining a presence in the celebrity hubs. For the Paris–Carmen–Lindsay–Edie Sedgwicks of the world (and any other aspiring starlet with more residual than talent), there is a real cost to keeping oneself away from the media and the celebrity hubs: The world will indeed forget about you. And thus we can see how stars make what appear to be bad decisions about where they show up: Girl pop bands do gigs in Las Vegas that aren’t accompanied by a big celebrity-hosted event. B-listers get paid to show up at tacky events sponsored by vodka brands that might pay the rent but won’t earn them a high celebrity profile. Heidi Montag posing for Playboy or going to a party at Hugh Hefner’s mansion allows her to branch out and capture a whole new audience, drumming up more media attention, and thus expanding her celebrity, but it also rapidly decreases her shot at an invite to the Vanity Fair Oscar party with its top film producers and directors. Invitations to the Oscars aren’t given out like coupons to Burger King. Even Paris Hilton was denied an invitation, despite her protests that she was a real film star. The options for a residual or B-lister may not be plentiful enough to turn down those extra events in Vegas like Celebrity Poker or the hair salon or boutique openings in LA. Even if by some extraordinary luck you land that invite to the Oscars, it will cost you $5,000-plus for dress, hair, makeup, stylist, driver; the list goes on. So those mediocre gigs and appearances at Vegas nightclubs will at least buy your dress if you somehow get the chance at the big time.

If it all seems a bit circular—the way individuals become stars by going to celebrity hubs and these celebrity hubs become what they are because the stars show up—then you’re sort of right, but not entirely. Fundamentally, some places possess basic qualities that enable them to become focal points of celebrity. People don’t become in-the-bright-lights stars in Kansas, but it’s not simply because Tom Cruise and his ilk don’t show up there. Kansas never had a chance to be a major player in the geography of stardom in the first place, because it lacked the necessary ingredients that catalyze success: a collective group of stars; a global media machine; an infrastructure of bars, clubs, and studios that enable the visual footage of celebrities to be captured in a glamorous context; and the surplus of wealth that bankrolls these various activities and places. Some of these attributes arise partially as a result of already being a celebrity hub (more stars move there because stars already live there and thus more media sets up shop), but others are necessary from the get-go for a place to even have a chance.10

Let’s start with the first element: In order to be a hub in the geography of stardom, a place needs a critical mass of celebrities and a collective group of individuals who socialize publicly and who are generally interesting to a wider public and, just as critically, to the media.11 How can we explain the concentration of celebrities? Often, they work in industries that are located primarily in one place, which means that to do their job they all have to work and live there as well. In order to be a gainfully employed film star, one has to be in Los Angeles for a good chunk of time. Even if an actor isn’t out at the clubs until three a.m., he or she must attend meetings with casting directors and producers located in Los Angeles, and filming often takes place in Hollywood back lots. Politicians may travel around their home state during Congress’s recess, but they’re expected to show up in D.C. regularly to debate and vote on bills and serve on committees.

However, it’s not simply a concentration of similar people. Back in the day, automobile workers all lived and worked in Detroit, but they were not celebrities. Celebrities are not just working in the same industries; the essence of their existence is that they are also very interesting to the media. Hollywood stars easily captivate us: They are attractive, fashionable, and act in movies we want to see, and the media loves to document them. Washington politicians may not be as good-looking or well dressed as George Clooney or Jennifer Aniston, but they also easily command an audience. There is rarely a dull moment inside the Beltway, whether Congress is passing a contentious bill or some senator had an inappropriate relationship with an intern. Conversely, Star Trek hobbyists are much less intriguing to a mass audience (even if they are relative celebrities), and most technology geeks in Silicon Valley are certainly uninteresting to mainstream consumers of popular culture and political intrigue.

An active media is the second important ingredient in a celebrity hub. The media needs to care, and the media located in these locales must be globally relevant in order to create megastars.12 A high-profile socialite in Dublin or Austin may be the talk of her town but rarely crosses over to mainstream stardom because Getty photographers or the New York Times or US Weekly are not showing up. Finally, there needs to be an infrastructure that lends itself to the cultivation of celebrities and the financial capital to keep opening establishments that are trendy and enticing.13 Because celebrity rests on the public’s obsession with individuals’ lives and personae, the media must find ways to obtain this information and capture it visually (what the historian Daniel Boorstin calls the “human pseudo-event”). Having clubs to fall out of, restaurants to glamorously walk into, and film and TV sets for impromptu lunches and romantic tête-à-têtes with costars is important to the media’s role in cultivating the celebrity personality. New York, Los Angeles, London, and, to an extent, D.C. all possess these characteristics, but the same basic qualities are necessary for other geographies of stardom too. In the world of country music, Nashville is an essential celebrity hub with the necessary big-hub attributes—just on a much smaller scale. Paris is an essential destination for fashion celebrities but not as important for the celebrity system as a whole.

Once these variables come together, the process of becoming a celebrity hub is set in motion. Economists call this self-reinforcing process “cumulative advantage,” but it’s as simple as success begets success.14 Having the basic infrastructure and capital to get the process moving accrues more capital and more people and more infrastructure necessary to perpetuate success, so that over time this dominance as a hub solidifies. We see it in Silicon Valley’s reputation as the world’s leading technology hub and New York’s and London’s positions as global financial capitals, and New York’s and Paris’s domination of the fashion industry. And we see it plain and simple in the geography of stardom.

Celebrity and the “Pseudo-Event”

One spring afternoon in London, my boyfriend (now husband), Richard, and I were strolling along the South Bank of the Thames. The South Bank is a formerly dodgy, now gentrified part of town that has a magnificent view of Westminster and Big Ben and is quickly becoming one of the most desired neighborhoods for the upwardly mobile and trend conscious. En route to lunch, we found ourselves in the midst of a great commotion under way at the Royal Festival Hall, an enormous entertainment venue located on the river. Massive crowds of people had formed a circle around a mysterious presence. Photographers were snapping away. When we investigated, we saw a massive ad hoc backdrop and a woman, some soap star whom Richard sort of recognized, smiling away in a bright red evening gown and far too much makeup. Her poses were obviously forced, and she seemed really uncomfortable. The backdrop indicated it was the BAFTA Television Awards, which are a pretty big deal in England (similar to the Emmys in the United States). Regardless, the little drama unfolding was bizarre. At three o’clock in the afternoon, here was this spectacle of a woman with about five inches of makeup and a tight prom dress smiling away in a gigantic open space along the South Bank, looking like she’d far rather be in sweats on her way to her own weekend lunch. Despite it being BAFTA, the scene seemed cheap and tacky, a far cry from the dazzling affair that it appeared to be in the newspapers and on TV. Yet many events are just like this in real life: quite starkly unspectacular and overly contrived. And rest assured, the photos taken and distributed to blogs and tabloids around the world make the most mundane events appear as the most exciting and sensational places to be.

The construction of a pseudoglamorous event along the South Bank demonstrates exactly how places like London, Los Angeles, and New York remain the big hubs. Celebrity is ultimately constructed by the players involved, and they have every reason to keep the system humming along. Media not only drives celebrity, it also helps establish the places and events that should be deemed important by the public, Boorstin’s “human pseudo-event.” Boorstin argues that modern culture, particularly the entertainment industries and politics, creates events that have the primary function of producing and feeding advertising and media.15 The events themselves are not relevant to the public until the media makes them so. In another world, the Oscars could be a subdued and private affair entirely dedicated to the recognition of outstanding performers in the film industry. Instead, with the cooperation of the television stations, newspapers, Motion Picture Association of America, and actors, it is the most high-profile celebrity event in the world. People in Ohio order pizza and throw Oscar parties to watch the event on TV. No one who lives in Los Angeles goes near Sunset Boulevard the entire weekend before the event for fear of drowning in a tsunami of limousines. Sure, the Oscars are important for the film industry, but the public cares about them because the media and the film industries have turned them into a glamorous, prominent event. The media showcases the stars to make them, well, even bigger stars. No wonder everyone wants an invite. The projection of posh glitz and resplendence at these events, whether the Grammys, the Oscars, movie premieres, or the Golden Globes, is necessary because these events drive all the TV, tabloid, and sponsorship revenue streams and maintain the public’s interest in particular celebrities. The film industry and the media benefit from making much ado about these events. The public’s preoccupation with the event is fundamental to perpetuating the phenomenon of celebrity and its related industries. However, if the powers that be don’t create celebrities, then the public has no one to celebrate.

And Getty, TMZ, ABC, and every other photographic and television entity are a part of the construction of the celebrity, not to mention all the clubs and restaurants that play hosts to Oscar after-parties. But consumers of celebrity care about celebrities only because the media makes them exciting and appealing. The marriage of celebrity with the media’s high-gloss finishing touch on these events makes them irresistibly enticing. We are drawn in by the reality of the unreality of it all. We like watching the Oscars because the event is filmed in February in the glorious Southern California late afternoon sunlight, when it’s cold, dark, and gloomy in most other places. At the Oscars, the people are beautiful and tanned, the dresses magnificent and colorful. There are a lot of very white, straight teeth. The carpet is a deep red and the columned Babylonian-themed Kodak Theater so impressive. The whole affair seems like such a glittering and enchanting backdrop to honor these film icons, the essence of Hollywood celebrity.

However, the red carpet mirage disguises the vast chasm between what the Kodak Theater looks like on TV and in photos and what it actually is: a suburban mall-like construction in the middle of a seedy section of Hollywood with psychics, wax museums, and strip clubs down the street. The media and the event organizers construct a glamorous image of the Kodak Theater that is completely removed from reality, even going so far as to hide neighboring stores behind curtains.16 Those who have not been to Los Angeles have no idea that this part of Hollywood is primarily streets of liquor stores, chain stores, and neon lights. The Walk of Fame is a bunch of grungy, faded stars on a littered sidewalk, not a single celebrity in sight. In fact, the most interesting part of Hollywood is the gaggle of tourists standing around confused, with “This is it?” expressions on their faces. The same can be said of Los Angeles’s Viper Room, a mile away on Sunset Boulevard, the mythical club where River Phoenix met his death after a drug overdose. A close-up picture of the club with stars falling out in the wee hours of the morning makes it seem like a wild and thrilling place. If you pan the shot out a bit, you’ll see a Subway sandwich shop, the Sun Bee Food and Liquor Mart, a dirty sidewalk, and a massive thoroughfare with cars flying by.

And here is where we return to the Cory Kennedy phenomenon. Kennedy’s success in cultivating her celebrity is a function of the way the media creates a new breed of celebrity. Kennedy is not simply a new Paris or a new Edie Sedgwick, famous for being famous. (Paris, after all, is a filthy-rich heiress with a sex tape. Sedgwick was a filthy-rich socialite with a drug problem and Andy Warhol’s attention. Kennedy comes from much more subdued circumstances.) Kennedy may hang with the celebrity set, but she has not been caught hoovering up cocaine or shoplifting. In another world, Kennedy would have likely lived a very normal life. But all the crucial factors combined to create a perfect channel for her to go from pretty high school girl to international girl-about-town in less than a year.

This is the story that makes celebrity so much a part of our lives today. Because the media is everywhere, with its endless conduits to report on stars, we think stars are everywhere, inhabiting our lives at all times. And we’re right. But this phenomenon is not a result of the A-list suddenly being more social or less elitist. Los Angeles, New York, and London remain the stomping grounds for the top celebrities, but these cities have also become destinations for the lesser known and the all-residual celebrities who use the media to cultivate stardom because the media has the ability to turn something ordinary into something glossy and sensational. Simultaneously, the media has chosen to focus on and sometimes create these new forms of stardom, thereby expanding the industry and the revenue generated through celebrity.

The geography of stardom outlines the basic behaviors of celebrities, but that’s not the same as providing a map for how to enter A-list territory. Yet by identifying the geographical patterns of top stars, one might have a chance at attaining celebrity status simply by showing up at the right places and being photographed at just the right time. The geography of stardom demonstrates that following stars is a good proxy for tracking the media. And if one can be in step with the media, one does have a real shot at celebrity. When millions upon millions can be made, it’s no wonder so many people are motivated to become stars, whether they are talented, all residual, or, like Cory Kennedy, a star utterly different from any form society has seen before.