IN CONTEXT

Physics and cosmology

1923 Edwin Hubble confirms the true nature of galaxies as independent star systems millions of light years beyond the Milky Way.

1929 Hubble establishes that the Universe is expanding, and that galaxies move away from us more rapidly the further away they are (the so-called “Hubble Flow”).

1950s American astronomer George Abell compiles the first detailed catalogue of galaxy clusters. Subsequent studies of galaxy clusters have repeatedly confirmed the existence of dark matter.

1950s –present Various models of the Big Bang predict that it should have generated much more matter than that which is currently visible.

The idea that the Universe might be dominated by something other than detectable luminous matter was first proposed by Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky. In 1922–23, Edwin Hubble had realized that “nebulae” were in fact distant galaxies. A decade later, Zwicky set out to measure the overall mass of the Coma cluster of galaxies. He used a mathematical model called the Virial theorem, which allowed him to calculate the overall mass from the relative velocities of individual cluster galaxies. To Zwicky’s surprise, his results suggested that the cluster contained about 400 times more mass than that suggested by the combined light of its stars. Zwicky called this staggering amount of unseen matter “dark matter”.

Zwicky’s conclusion was largely overlooked at the time, but by the 1950s, new technology had opened up new means of detecting non-luminous material. It was clear that large amounts of matter are too cool to glow in visible light but still radiate in infrared and radio wavelengths. As scientists began to understand the visible and invisible structure of our galaxy and others, the amount of “missing mass” fell substantially.

The invisible is real

The reality of dark matter was finally recognized in the 1970s, after US astronomer Vera Rubin mapped the velocity of stars orbiting in the Milky Way and measured the distribution of its mass. She showed that large amounts of mass are distributed beyond the galaxy’s visible confines, in a region known as the galactic halo. Today it is widely accepted that dark matter constitutes around 84.5 per cent of the mass in the Universe. Any hopes that it might actually be normal matter in hard-to-detect forms, such as black holes or rogue planets, have not been borne out by research. It is now thought that dark matter comprises so-called Weakly Interacting Massive Particles (WIMPs). The properties of these hypothetical subatomic particles are still unknown – they are not only dark and transparent, but they do not interact with normal matter or radiation except through gravity.

Since the late 1990s, it has become clear that even dark matter is dwarfed by “dark energy”. This phenomenon is the force accelerating the expansion of the Universe, and its nature is still unknown – it may be an integral feature of space-time itself, or a fifth fundamental force known as “quintessence”. Dark energy is thought to account for 68.3 per cent of all the energy in the Universe, with the energy of dark matter amounting to 26.8 per cent, and normal matter a mere 4.9 per cent.

If our galaxy’s mass distribution matched that of its visible matter, then stars in the galaxy’s outer disc would move more slowly at greater distances from the massive centre. Vera Rubin’s research found that beyond a certain distance the stars tend to move at a uniform speed regardless of their distance from the hub, revealing dark matter in the galaxy’s outer halo.

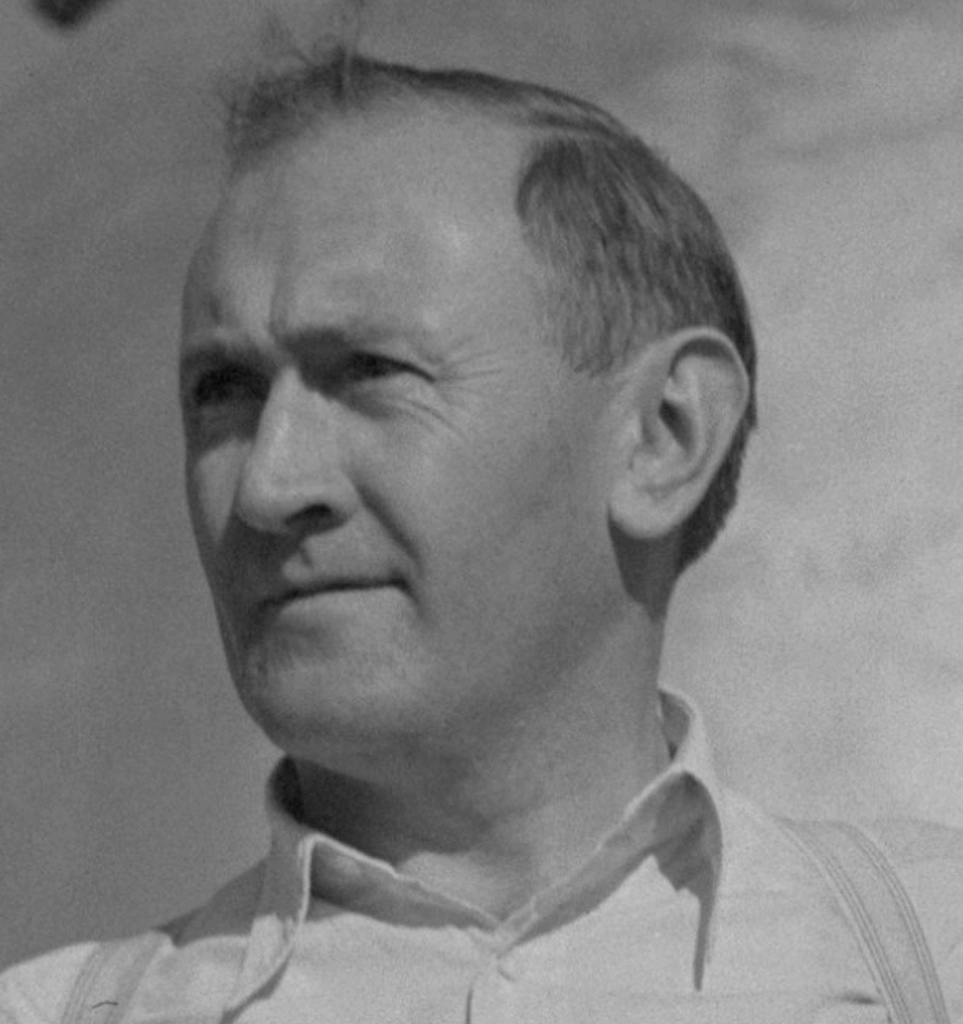

FRITZ ZWICKY

Born in Varna, Bulgaria, in 1898, Fritz Zwicky was raised by his Swiss grandparents and showed an early talent for physics. In 1925, he left for the USA to work at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), where he spent the rest of his career.

Aside from his work on dark matter, Zwicky is also known for his investigations into massive exploding stars. He and Walter Baade were the first to show the existence of neutron stars intermediate in size between white dwarfs and black holes, and coined the term “supernovae” for the enormous stellar explosions in which these massive stellar remnants are born. By showing that one class of supernovae always reach the same peak brightness during their explosions, they also provided a means of measuring the distance to far-off galaxies independently of Hubble’s Law, paving the way for the later discovery of dark energy.

Key works

1934 On Supernovae (with Walter Baade)

1957 Morphological Astronomy

See also: Edwin Hubble • Georges Lemaître