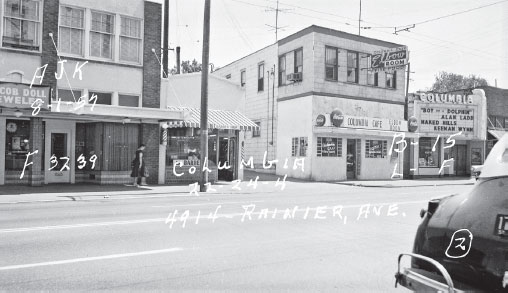

Crawford’s Sea Grill, its tower spelling SEA FOOD in large neon letters, was at water’s edge on Elliott Bay. Author’s collection.

In the Neighborhoods

Former mayor Greg Nickels once described Seattle as a “city of neighborhoods”—127 of them according to the city’s website. How did they come to be? Some of them were once independent towns. Others grew around transportation corridors—in early days, at stops along the interurban trolleys north and south out of Seattle; later, as the automobile became part of the scene, along highways or at important road junctions. The Green Lake neighborhood grew near the lake of the same name. The University District, as its name suggests, grew up near the University of Washington. Others? Who knows why? They each have their own story to tell.

Seattle’s neighborhoods were tied together by a web of arterial streets. Many neighborhoods had (and still have) their own business districts, and it was natural for restaurants to appear both in the local downtowns and along the main routes between them. Industrial areas also attracted eateries—workers in factories and around the harbor needed someplace to do lunch. Overall, the quantity of restaurants in Seattle’s outliers exceeded the number available in the central business district.

Seattle’s Original Neighborhood

In the 1880s, Seattle was a fairly compact city on the shore of Elliott Bay, clustered around the site of Henry Yesler’s mill and hemmed in on the east by remnants of dense forest. About a mile to the north, another community—Belltown—had arisen with its own business district, mill, wharves and residences. What stood between Seattle and Belltown was Denny Hill, several hundred feet in height and, until it was washed away by the Denny Regrade project, a barrier to easy travel between the two places.

It’s known that eateries and at least one hotel were established by the time of the great fire of 1889. The Dakota Restaurant was located at 2417 Front Street, the New Orleans was located at the corner of Front and Battery Streets and Mary Yates and Claude Brown also ran restaurants in the neighborhood. Belltown escaped the flames, and the day after the fire, Bell’s Hotel (also called the Bellevue House) was said to be the only restaurant left in Seattle. Richard Dodge, proprietor of the Bellevue Dining Room, went to great lengths to take care of the hungry men and women who plodded north from the burn zone in search of a meal.

By the turn of the century, there were at least four restaurants in Belltown, along with a saloon and two confectioneries. The district experienced little growth for the next few decades, even after Denny Hill was removed. In 1940, Herman Doder was running Herman’s Cafe at 2309 First Avenue, the Bell Town Cafe was at 2207 First and Christian Steen had another restaurant up the block at 2219.

A new and different Belltown Café appeared in 1979 at 2313 First Avenue, just as the area was beginning to revive. The café’s menu offered chicken breasts stuffed with prosciutto and mushrooms, a pork-sausage-and-rice mixture wrapped in cabbage leaves and creamy soups and fish mousses, along with several vegetarian entrées. Co-owners Ben Marks, Phil Messina and Pat Tyler highlighted family recipes; everything—bread, sauces, dressings, desserts—was made on-site. Today a Brazilian-themed restaurant, the Grill From Ipanema, occupies the site. Belltown, having been rediscovered and rebuilt, is considered one of the most desirable (and expensive) places to live in Seattle.

Even longtime Seattleites are surprised to learn that the city has 200 miles of waterfront—about 54 miles of saltwater shoreline and another 147 miles along Lake Washington, Lake Union and the Ship Canal. With views westward toward the Olympic Mountains and east to the Cascades, it’s no wonder that many restaurants have chosen the waterfront to call home.

The early settlers probably didn’t take scenery into consideration when the first restaurants appeared downtown. Any restaurant built on Front or Commercial Streets was on the waterfront—at the time, Elliott Bay lapped up almost to the streets. It wasn’t until the 1930s that restaurateurs began locating their eateries along the water specifically to take advantage of the views.

Among the first was Crawford’s Sea Grill, on Elliott Avenue about a mile northwest of the downtown core. In July 1940, the Seattle Daily Times announced the opening of the Sea Grill at 309 Elliott Avenue. Veteran restaurateur C.C. Crawford had been planning it for ten years; designed to take advantage of the sweeping view of Elliott Bay, it was built and completely equipped for $31,000. The glass-enclosed main dining room seated 188 patrons and provided an unobstructed view of Puget Sound and the Olympics. Crawford’s motto was “a showplace on the shore of Puget Sound”; his goal was to specialize in “serving the widest variety of sea foods, all prepared on a specially designed broiler, with olive oil used exclusively in the preparation.” The menu featured all kinds of seafood: scallops, lobster, snapper, salmon, smelt, sole, tuna, clams, shrimp, oysters, abalone and halibut, plus juicy broiled steaks, chicken and turkey roasted to perfection.

Only five months after opening, the restaurant had become so popular that an addition was constructed to increase the seating space. Unfortunately, C.C. Crawford didn’t have much time to savor his restaurant’s success, as he passed away in 1942. J.E. Meaker took over for a few years before selling out to Nick Zanides and moving to Tacoma, where he opened a Crawford’s. Zenides remodeled the Sea Grill in 1948, creating a congenial, modern, marine ambiance with an interior décor of ship ornaments, seashells, marine life, fishnet curtains and other decorations stressing marine atmosphere. A cocktail lounge, the Coral Room, was added, along with a garden where it was claimed five hundred varieties of roses were grown. Ivar Haglund bought the property in 1965 and moved his Captain’s Table there from its original Fifth Avenue location. The Captain’s Table closed in 1991, and today a medical facility occupies the property.

Crawford’s Sea Grill, its tower spelling SEA FOOD in large neon letters, was at water’s edge on Elliott Bay. Author’s collection.

The Ocean House opened in 1941 just one hundred yards farther along at 375 Elliott Avenue. Initially owned by Evelyn Howie, within a year, it was taken over by Jennie Mangini, with Wener Gloor as seafood chef. Not surprisingly, the Ocean House specialized in seafood but also offered broiled steaks and roast chicken. Lunch was served daily. In 1973, the Ocean House closed; all the equipment was auctioned off. A year later, a new Ocean House appeared at 920 Aurora Avenue, quarters previously occupied by Les Teagle’s; it closed in 1979. Today, there’s an office complex on the site of the original Ocean House—the later Aurora Avenue site is an office tower.

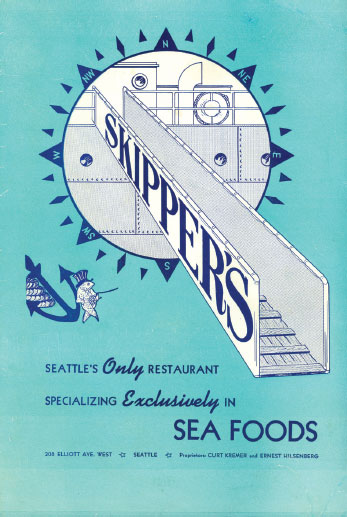

Skipper’s Seafood Restaurant was at 208 Elliott, where the Homewood Suites hotel is today. The vaguely ship-shaped restaurant was built by Ernest Hilsenberg and Curt Kremer in 1942. The nautical theme included a lighthouse, pilot house and porthole-style windows; inside, tables were decorated with charts, and the walls were hung with pictures of ships. A 1960 visitor commented:

Skipper’s has been one of the best restaurants to get the small oysters, Olympias, Quilcenes and Cove, cooked so gently to make them tender. The other types of seafood are the best ever and served in true nautical fashion. Having two congenial hosts, there has always been one of them standing by to greet the patrons.

In 1960, the restaurant became George Olsen’s Seven Nations, with a decor that “connected East and West in a contemporary mode with an international feeling. Objects of art from India and South America stand out against the white natural woods of the interior…[and] the waiters wear white jackets and French aprons.” It didn’t last long; by 1962, a Chinese restaurant, the Double Joy, had moved in. Two years later, Stuart Anderson took a long-term lease on the building and made it the first of his Black Angus Steak Houses, a chain that eventually grew to over one hundred locations.

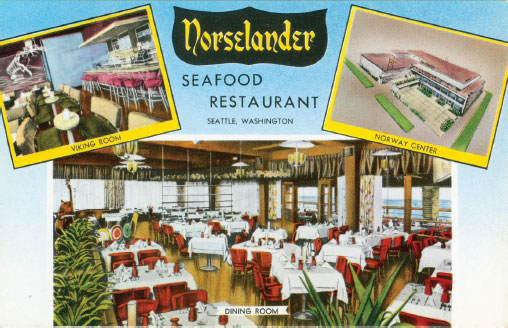

The Norselander, at 300 Third Avenue NW, specialized in “everything edible that swims on Northwest waters.” The restaurant opened in 1951 on the top floor of the Norway Center, a modernistic L-shaped building just off Elliott Avenue. Specialties of the house included the Captain’s Dinner (salmon, oysters, shrimp, lobster), prawns with fluffy rice, crab Newburg and Alaska shrimp curry, along with deep-fried prawns, crab or oysters; clams; salmon; trout; and other non-seafood dishes such as steaks, chops and poultry. Roy Peterson was the owner, with Ole Madsen as manager and Bill Clark the chef. The Viking Room was the cocktail lounge, with a marine theme of fishnets hanging over the walls and an entrance of sea-roughened pilings. The Norselander survived into the 1980s; now even the building is gone, demolished in 2008.

Ship-shaped with porthole windows and a lighthouse tower, everything was nautical at Skipper’s. Author’s collection.

Of Danish descent, Holger Nielsen introduced smorgasbord to the Seattle waterfront when he opened the Selandia in 1951. (Selandia is the Latin name for the Danish island of Sjælland.) Not long after Nielsen threw the doors open, a Seattle Times restaurant critic raved: “In the course of a scant five months the Selandia has earned itself a reputation seldom attained in less than a period of years.…The Viking table’s 72 square feet of surface is laden for your pleasure with not less than fifty-five varieties of savory taste-thrills.”

The lavish smorgasbord included Scandinavian specialties such as rullepolsa (Danish spiced meat roll), leverpostej (Danish liver pâté), biff à la Lindstrom (a Swedish version of ground steak), sylta (head cheese), Swedish meatballs and brown beans and planked Dansk hakkebof (ground sirloin tip sautéed in brown butter with pan-fried onions). More traditional items included poached salmon, shrimp, crab, roast beef and boiled tongue. A house specialty was skidden eggs, “a Nielsen invention made up of hardboiled eggs buried in a creamy mustard sauce.” The table always held at least four varieties of cheeses, deviled eggs, stuffed tomatoes and salads. Dessert included apples baked with cinnamon and Swedish pancakes with lingonberries. Nielsen advised diners to make at least three plate-filling circuits around his laden table. The smorgasbord dinner was available daily from 5:30 p.m. with a more limited lunch version from 11:30 a.m. until 2:00 p.m. An à la carte menu, with entrées more familiar to Americans, was offered all day. Popular though it was, the Selandia only lasted for about nine years; it had disappeared by 1960.

On Seaview Avenue, where Salmon Bay meets the sound, is Ray’s Boathouse. Ray Lichtenberger built a boat rental and bait house at this site in 1939, adding a coffee shop a few years later. In the 1950s, Marvin and Dorothy Rosand opened Rosand’s Seafood Cafe and ran it for about twelve years. The restaurant became the Breakwater, then the Viking, before being absorbed into the boathouse complex and simply called Ray’s Boathouse. Ray’s has burned and been rebuilt twice and is still in business on its choice piece of real estate with territorial views of the sound and the Olympic Mountains.

Several well-known restaurants were located along Westlake Avenue on the edge of Lake Union. Franco’s Hidden Harbor was within the Marina Mart at 1500 Westlake N, a complex of shops oriented toward the maritime trade. John Franco ran the place in partnership with his father, Marco. The Hidden Harbor revealed itself in 1954, billed as “something new in Seattle dining…nestled in the Pacific Coast’s finest yacht marina.…A shellfish specialty house, this is the only Seattle restaurant on waterfront level. Surrounded by yachts. Meals served on open dock if desired.” Marco and John had previously operated Franco’s Cafe on Western Avenue; after World War II, they sold it and bought the Marina Grill in the Marina Mart, which they recalled as “a seven-stool lunch counter and cigar counter upstairs and only two small rooms downstairs,” and completely remodeled the place. The restaurant was actually located over the lake, so whenever a serious plumbing problem developed, a diver had to be called in to solve it.

Not to be outdone, Selandia also had a tower with its name in neon and an awning-covered entrance. MOHAI, PEMCO Webster & Stevens Collection, 1983.10.16743.

For many years, the chef was Poppa John (real name, Themistokles Georgeos Karamanos), who in his early days had worked at the Brown Derby in Hollywood, California. The lunch menu featured salads of avocado and fresh Dungeness crab, shrimp louie, Dungeness crab louie, Dungeness crab omelet, crab and cheese dip, Dungeness crab on toast and cheese sauce and sliced turkey breast with bacon and asparagus spears topped with a house-specialty cheese sauce. Dinner entrées varied daily but often included braised sirloin tips, fried Pacific baby clams, prawns kebob Hawaiian and what a restaurant reviewer called “an astonishing array of seafood dishes”—oysters and crab, broiled salmon, grilled halibut, grilled filet of sole, prawns, scallops, lobster tail, shrimp and abalone. Somehow, steaks—from filet mignon to T-bone—also crowded onto the menu along with other non-seafood dishes. Today, the Marina Mart is still there; the Hidden Harbor is long gone.

Oyster Pepper Roast

½ green pepper, finely chopped

2 tablespoons olive oil

1 cup catsup

¼ cup water

2 tablespoons lemon juice

½ teaspoon Worcestershire sauce

1 dash soy sauce

1 dash Tabasco

50 to 65 oysters

Parsley

Toast points

Lemon wedges

In a saucepan, sauté finely chopped green pepper in olive oil until the peppers are tender. Add and blend 1 cup catsup, water, lemon juice, Worcestershire sauce, soy sauce and Tabasco sauce.

Add oysters to sauce and cook until done. Serve in individual casserole dishes garnished with parsley, toast points and lemon wedges.

Fresh Dungeness Crab Fry Legs

3 tablespoons butter

24 to 28 jumbo crab legs

1 ounce sauterne wine

20 large button mushrooms

Melt butter, add crab legs, wine and mushrooms and sauté for 3 minutes.

Marco Franco looks a bit uncomfortable surrounded by adoring waitresses in this 1956 photo. University of Washington Special Collections, JEW0422.

Moultray’s Four Winds was at 900 Westlake, at the southern end of Lake Union, and opened in 1955, a year after the Hidden Harbor. Chris and Bill Moultray built their restaurant atop a former 1900-era ferryboat called the City of Everett. The pirate theme—“Look for the Pirate Atop the Boat”—carried over inside the restaurant, where waitresses dressed in buccaneer costumes served up seafood, steaks and prime rib. Creoleseasoned dishes were a specialty. By 1965, the Four Winds had become the Surfside 9, a dance club. The following year, the bilge pumps that kept the old ship afloat failed, and the City of Everett sank to the bottom of Lake Union. It was raised but promptly sank again, this time for good.

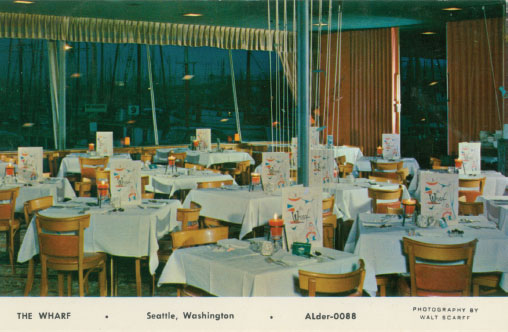

The Wharf was part of the million-dollar Fishermen’s Terminal project constructed by the Port of Seattle and completed in 1952 at the south end of the Ballard Bridge. The Wharf Restaurant and Coffee Shop overlooked the fishing-fleet moorage, largest on the West Coast, and included a taproom and separate cocktail lounge.

Moultray’s was pirate country; a pirate figure atop the old ferryboat beckoned guests to board. There was also a Moultray’s in Yakima. Seattle Times.

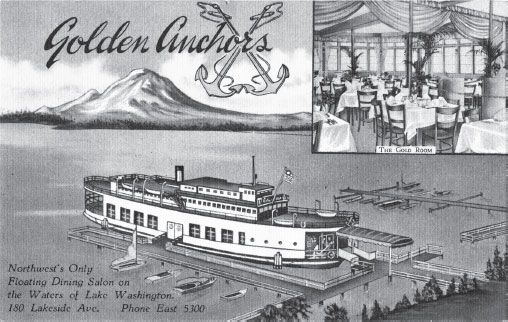

Golden Anchors sat atop the City of Everett, the same recycled ferryboat that later was used by Moultray’s Four Winds. MOHAI, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, 1986.5.15.70.

It’s said that the Wharf had a split personality; Jack Curle, the manager, said he had two separate restaurants and cocktail lounges under the same roof:

They are served by the same kitchen, but each caters to a completely different clientele. On one side are the hard-working and roughly dressed commercial fishermen whose boats are moored nearby. The coffee shop and Moby Dick cocktail lounge cater to them, while the plush dining room and fancier Mermaid Room entertain more genteel family and club groups.

The Wharf grew over the years, eventually reaching a seating capacity of four hundred and becoming a popular nightlife destination, booking many musical acts and other entertainment. The Wharf made it into the 1980s before vanishing; today its place as Fishermen’s Terminal’s premier dining place has been overtaken by Chinook’s at Salmon Bay.

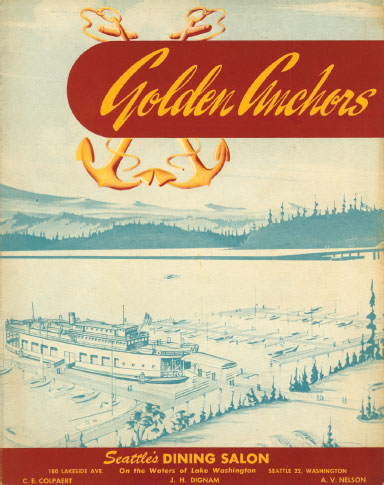

On the Lake Washington side of Seattle was the Golden Anchors at 180 Lakeside Avenue, near Leschi Park. It opened in 1945 aboard the City of Everett, the same ill-fated ferry that later carried Moultray’s Four Winds. Nearby residents were opposed to the idea of a dine-dance place operating in their quiet neighborhood, but the city eventually issued a license over their objections. Perhaps because it was afloat on fresh water, not salt, the Golden Anchor’s menu didn’t offer much seafood; typical fare included fried chicken, pot roast and sirloin steak. The Golden Anchors doesn’t seem to have lasted long; it was offered for sale after only a year and a half of business, and the old ferryboat was towed over to Lake Union to meet its ultimate doom.

QUEEN ANNE

Queen Anne Hill, one of the so-called seven hills of Seattle, defines the skyline two miles north of downtown. There are actually two Queen Anne neighborhoods: one at the south base of the hill around Queen Anne, Mercer and First Avenues and another at the top of the hill a mile farther north (and three hundred feet higher) along Queen Anne Avenue.

Lower Queen Anne developed first, as settlers cleared off the trees at the foot of the hill to build homes. Upper Queen Anne didn’t take off until a streetcar line built up it in 1902; before then, the grade was considered too steep and the hill too densely forested to be developed.

Restaurants began appearing in both Upper and Lower Queen Anne around 1930. The Queen Anne Cafe, at 15 Boston Street, atop the hill, had opened by that year. Also on Boston, on the west side past Queen Anne Avenue, was the Hill Top Cafe. Several restaurants owned by Lena Grollmund and Herman Peterson gathered at the top of the counterbalance (so-called as an assist to streetcars climbing the hill) to service hungry trolley riders. In the 1950s, the Red Snapper Cafe could be found at 1833 Queen Anne Avenue.

In Lower Queen Anne, Blanche J. and R.A. Matthews were the proprietors of Matt’s Log Cabin, a hamburger shop, in 1934. Matt’s was located at 435 Queen Anne Avenue. Another Queen Anne Cafe—no relation to the one on top of the hill—was run by Thomas Jensen at 527 Queen Anne in the 1940s. A restaurant called the King Grill, 605 Queen Anne, was in business in 1951. The entire character of Lower Queen Anne changed when the Century 21 Exposition came to town; located only a few blocks from the fair site and the iconic Space Needle, the neighborhood benefited mightily from the overflow business.

WESTLAKE AVENUE

Westlake Avenue originates in downtown Seattle and for many years was the main route north out of the city toward the Fremont, Phinney Ridge, Greenwood and Green Lake neighborhoods. Aurora Avenue and later Interstate 5 carry the bulk of north–south traffic, but Westlake remains an important arterial. Not surprisingly, a number of cafés and lunch places sprang up along Westlake, particularly in the light industrial district between Denny Way and Mercer Street.

Built of logs and looking like a Wild West stockade, the Bungalow, at 905 Roy Street, disappeared long ago. Washington State Archives Puget Sound Regional Branch.

There were the Dart In Cafe, Roy’s Cafe and the Westlake Grill within a few blocks of one another. Just north of Denny was the E&B Cafe (later known as the J&K Cafe; it’s not known who E, B, J or K were). The Bungalow, a burger joint and tavern, was at 905 Roy Street, a block west of Westlake. It appeared in 1940 but was gone by the end of the decade. The sites of all these eateries have been overwhelmed by the explosive growth of the South Lake Union district.

FREMONT

Because Westlake Avenue hugs the east side of Queen Anne Hill in a narrow stretch of land along Lake Union, there wasn’t much room for restaurants to build up other than those actually on the waterfront. At the north end of Queen Anne Hill, Westlake merges with several other streets to cross the Fremont Bridge (built in 1917) into Fremont.

Even after being discovered and gentrified, Fremont (which modestly bills itself as “the center of the universe”) seems frozen in time; most of the buildings date to about 1910. The community grew with the early timber industry; it sits at the outlet of Lake Union, an ideal spot for sawmills. Once a separate town, it was incorporated into Seattle in 1891. During the heyday of streetcars, Fremont became an important intersection for trolley lines running north, south and east.

Over the years, a number of restaurants functioned in “downtown” Fremont, including the Metropolitan Cafe at the corner of Fremont Avenue and North Thirty-Fourth. The Fremont Drug Company originally occupied the building, but it had become a café by 1914. Now it’s a Starbucks. Just up the block was the Club Cafe. Around the corner where North Thirty-Sixth Street heads west to Ballard was the Spa Cafe, run by William and Verna Seder. In 1955, William Seder, despondent over financial problems, took his own life by turning on all the gas burners on the kitchen stove; before he did so, he saved his pet parakeet by taking its cage out onto an open porch. He was only thirty-seven years old. In later years, a typical neighborhood bar with live music occupied the Spa’s location; today, it’s a vegetarian restaurant.

Across the street from the Metropolitan stands a building that has been home to restaurants since at least 1910. It was first the Bryant Cafe; after a few years as a drugstore, it became Peggy’s Fountain Lunch and, in the 1970s, the Dancing Machine Tavern. Between 1981 and 2012, it housed Costas Opa, a fine Greek restaurant sorely missed by Fremocentrists, as the locals call themselves.

Next door on Thirty-Fourth Street was the Fremont Cafe, operated for many years by Nick Theotokis. A few feet east on Thirty-Fourth was the Aloha Cafe. North of Fremont, heading uphill toward Phinney Ridge, stood the Hob Nob Cafe at 4909 Fremont Avenue. In earlier days, it was called the Woodland Sandwich Shop; by 1968, it had become the Djakarta, an Indonesian restaurant. There’s an apartment complex at that location today.

PHINNEY RIDGE

Fremont Avenue intersects North Fiftieth Street; turn west onto Fiftieth, follow the road as it curves north a few blocks later and you’re on Phinney Avenue as it heads north to the Greenwood district. On the east side of the street is Woodland Park, one of Seattle’s largest parks and home to the Woodland Park Zoo. It was natural that cafés and lunch counters would go up near the park to take care of visitors; over a half dozen could be found along the ten-block length of Phinney Avenue bordering the park.

As early as 1928, there was a fountain lunch–hamburger place at 5409 Phinney; it later became McGrath’s Park View Lunch. The Woodland View Cafe was located at 5817 Phinney Avenue; Val’s Cafe, at 6020 Phinney, was just north of the park. The 1932 city directory listed Hans Romstead, John Manos, Paul Davison and Mabelle Patten as operating restaurants along this stretch of Phinney. (In those days, it was common for restaurants to be listed by the owner’s name.) All of these places have vanished.

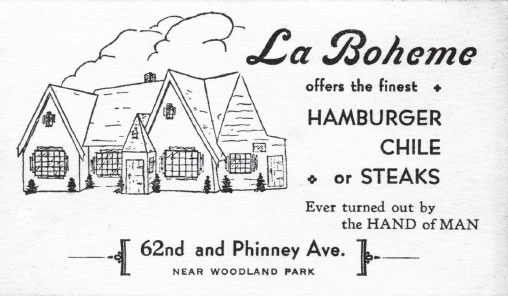

Still standing at 6117 Phinney is the distinctive building long known as La Boheme. Looking like it was constructed in the front yard of a house, its English cottage–style design makes a distinctive sight. La Boheme opened soon after the end of Prohibition in 1934 and served a limited menu of hamburgers, steaks and chili—“the finest ever turned out by the hand of man.” Known to regulars as “La Bow,” it changed ownership in the late 1990s and is now Sully’s Snow Goose Saloon.

Another neighborhood favorite, recently closed, was at 6412 Phinney Avenue. In early days, it was known as the Snack Bar, but by the time Jeanne Mae Barwick took over in 1988, it had long been renamed the Phinney Ridge Café. Weekends found customers waiting on the sidewalk to get through the doors. Specialties included smoked salmon benedict, breakfast burritos, homemade cinnamon rolls and an unusual breakfast pairing called Shake and Eggs—a milkshake served with eggs done as you like ’em. Mae’s Phinney Ridge closed in 2013—another casualty on the dwindling list of Seattle’s classic cafés.

La Boheme, looking like an English cottage, could have been mistaken for a private residence. The building still stands along Phinney Avenue. Author’s collection.

Just up the street from Mae’s at 6557 Phinney, where the street makes a jog to the west and continues up Greenwood Avenue, a little café called Marian’s Lunch operated for a short time in the early 1950s. After a spell as home to various types of stores, the vacant building was purchased by Sharon and John Hughes and opened as a specialty restaurant called Eggs Inc. in 1970. The specialty was omelets—always cooked to order by either John or Sharon (while the other waited on tables), almost always with a line of customers waiting to get in, the place was so popular. The house favorite was called the Five-to-One: ham, black olives, mushrooms, cheddar cheese and onions. Other omelets had names like the El Paso, Barcelona, Bavarian, Canadian and Dungeness. Lunch-sized omelets were made with three eggs; five eggs went into the dinner version. Eggs Inc. eventually added other items to the menu for folks with dietary restrictions to eggs, including sandwiches, homemade pies and two new specialties: beef burgundy and chicken breasts in orange sauce.

What was Costello’s Cafe at 6724 Greenwood Avenue in 1951 became the Stumbling Goat Bistro. In the 1930s, Grace and Louis Perkins ran the Emerald Confectionery and Lunch at 6732 Greenwood. By 1968, it had become the 68th Street Tavern; until recently, it was the Kort Haus, a hamburger place. The building housing both the Stumbling Goat and the Kort Haus was purchased by real estate developers and is scheduled for demolition, though both restaurants hope to reopen in the new building.

Another burger place was Matt’s Hamburger, a small shop with only nine stools and two tables located at 7118 Greenwood. Matt’s was open twenty-four hours a day in 1936, when a fried chicken dinner cost just twenty-five cents. A few years later, it had become the Ridge Cafe; in 1951, it was called Lou La’s Grill. Later yet it was the Greenwood Cafe. An art gallery later occupied the premises.

In 1951, Noble’s Fountain Lunch was located at 7307 Greenwood; it later became the 4-Rs Cafe and, by about 1970, was the Harbin, Seattle’s first northern-style Chinese restaurant. The Harbin moved out, and the Greenwood Mandarin Restaurant moved in, with an extensive menu (over one hundred items) featuring special dishes such as palace beef, garlic chicken and princess chicken. The Greenwood Mandarin closed in 2014, and the building was demolished to make way for a bank branch.

Another location with a long restaurant history is 7419 Greenwood. John McGuirk was operating there as early as 1932. In the 1960s, it was Farrell’s Cafe, whose slogan was “Bring the Family for Sunday Dinner—Eat Better for Less.” For many years, it’s been Yanni’s Greek Cuisine.

GREENWOOD

The intersection of Greenwood Avenue and North Eighty-Fifth Street defines the Greenwood neighborhood’s business district. Over the years, several dozen restaurants have come and gone along this quarter-mile-long stretch of Greenwood Avenue; no old-timers remain, but many have appeared to take their places.

In 1930, Bill Fenton opened Creamland at 8402 Greenwood Avenue, when he was just eighteen years old. He worked seven days a week in the shop, often getting in at one o’clock in the morning to start making his ice cream. In 1958, robbers broke though Creamland’s back door and made off with $550, of which $374 was nickels—that’s over eighty pounds’ worth. After forty-seven years, taking only a single vacation during that time, Bill Fenton retired after scooping his last ice cream cone in October 1977. New owners Darryl and Pat Ryan took over for another dozen years and kept intact the old Creamland ambiance. Across the street was the Wee Hamburger Shop. After years of accommodating non-restaurant businesses, today the building is home to Kouzina, a Greek restaurant.

In 1951, the building at Eighty-Fifth and Greenwood, once occupied by the City Drug Store, was taken over by Randle’s Cafe. The name soon changed to Jacken’s Grill. Jacken’s featured full-course dinners in a family atmosphere with cocktails by an open fireplace in the Stardust Room, a separate lounge. In 1964, a complete steak dinner cost $2.50; prime rib was $3.00. Tuesday night was an all-you-can-eat smorgasbord from 6:00 until 9:00 p.m. Jacken’s was still Jacken’s in 1980 but a few years later became DiMaggio’s, where an all-you-can-eat salad and pasta bar—six choices of pasta, four different sauces—was priced at $5.95. Currently, the building serves as an events center called Greenwood Square.

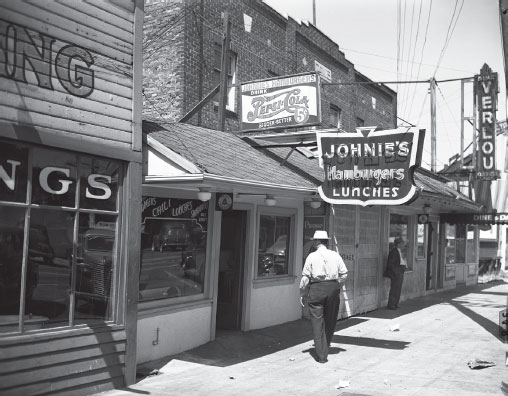

Johnie’s Cafe was shoehorned in between two buildings in Greenwood, just north of Eighty-Fifth Street. MOHAI, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, 1986.5.12382.1.

There’s an interesting bit of hamburger shop history on the west side of Greenwood north of Eighty-Fifth. In the 1930s, John and Florence Ring operated Babe’s Hamburger Shop at 8601 Greenwood. They apparently sold the place in 1936 and moved a few doors south to 8635, where they opened Johnnie’s Hamburgers. One hundred feet farther along, but twenty years later in time, sat Johnie’s Cafe, a burger joint with nine stools and four booths, at 8523 Greenwood. If there was a connection linking Johnnie’s and Johnie’s, it’s been lost over time. Between them were a dine-and-dance place called Verlou’s and a Chinese restaurant, the China Inn.

The Doodle Sack Drive-In, as it looked in 1956. “Doodle sack” is a slang term for bagpipes. Seattle Municipal Archives, 75756.

Marie Nordquist was the original owner and namesake of Marie’s Cafe at 8549 Greenwood. The story goes that she hired a cook from Oregon, a man named Harold Smith, who brought with him a recipe for blue cheese salad dressing that quickly became a house favorite. They began bottling the dressing in Marie’s basement for sale to customers, and its fame spread. In the 1950s, Smith bought the café from Marie, took on Werner Ferber as a partner and set up a bottling works to expand the salad dressing production. They marketed the dressings through several supermarket chains, and within a few years, the dressings business had far surpassed the restaurant, with over $1 million in annual revenues. Over twenty other varieties were offered, including creamy Italian garlic, thousand island and apple glaze, though the blue cheese dressing remained the most popular. Meanwhile, the café struggled along, running afoul of the liquor control board and health department numerous times in the late 1970s. By 1983, Marie’s had become the Baranof, still Greenwood’s favorite neighborhood bar. Marie Nordquist passed away in 2008. The dressings live on, though today they’re made in California, not Greenwood.

Scotty’s mascot fish was decked out in top hat and cane, as the cover of this menu shows. MOHAI, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, 1986.5.15.90.

In 1951, a place called the One Hundred Per Cent Lunch sat in what is now the Safeway parking lot at 8728 Greenwood Avenue. Across the street and a block north was the Doodle Sack Drive-In at 9009 Greenwood. It lasted for about ten years before being replaced by apartments.

West on N Eighty-Fifth from the Greenwood Avenue intersection was Hazel’s Cafe. Scotty’s Fish & Chips was up the street at 323 NW Eighty-Fifth. Owner E.W. Robert “Scotty” Wylie operated his seafood place for sixteen years using a fish-and-chips recipe he claimed was handed down from father to son at the Cannon Mills Place Fish and Chip Shop in Edinburgh, Scotland. His menu also listed grilled halibut and salmon; fried filet of sole, shrimp and clams; and oysters in season. Around 1950, Scotty relocated to 8318 NW Eighty-Fifth, and the Fish Net Cafe went into his original location. Also along this section of Eighty-Fifth was a place called the Rattleyboo Cafe at 802 West. It apparently didn’t last long.

GREEN LAKE

Two business communities developed at Green Lake—one on the east side, another three-quarters of a mile away at the lake’s northern end. On the east side was Warling’s Restaurant at 7115 Woodlawn Avenue, a block away from the lake and adjacent to the Green Lake Theatre. Cliff Warling opened his restaurant, described as “the Northwest’s most modern and distinctive,” in 1949. That year, restaurant reviewer Nat Lund found Warling’s “a wise choice for folk in a steak-eating mood” with nine different varieties; top of the line were the New York–cut sirloin and porterhouse, which came with a tossed green salad, potatoes (baked, french fried or au gratin—a house specialty served en casserole with a mild cheese sauce), rolls and beverage for $2.75. Other broiler items included chops, lobster tails and Chinook salmon with melted butter. Filet of sole and butter-fried chicken served with hot baking powder biscuits and honey were also on the menu. Lund described Warling’s as a good lunch choice also, with decor “as tasty as the food—restful green walls, with stylized fish, and soft cove lighting” and a fourteen-seat bar with a mirrored ceiling and real bar chairs instead of stools. By 1969, Warling’s had become the Little Red Hen, which it still is today.

Just down the street from Warling’s, Raymond Buell’s Fountain & Grill was a prototypical neighborhood hamburgers-and-milkshakes sort of place. Burgers and a dozen different kinds of sandwiches were on menu along with short-order steaks, chili and fish and chips. An entire page of Buell’s menu was devoted to ice cream mixed drinks (shakes, malts, ice cream sodas and floats), sundaes, freezes and soft drinks. Buell’s also served limited breakfast fare: ham or bacon with two eggs (seventy-five cents) or a ham and cheese omelet for eighty cents. Buell’s was located at 7101 Woodlawn Avenue. A few steps away were two more lunch counter places: Green Lake Lunch & Billiards at 415 E Seventy-Second Street and the Green Lake Bowl Cafe on Ravenna Boulevard.

A block away from Buell’s, facing onto the lake at 7116 E Green Lake Way, was the Hula Hut Barbecue & Freeze. Although it had already been around for four years, the Hula Hut celebrated its grand opening in 1954 with nineteen-cent hamburgers, hot dogs, milkshakes and homemade apple pie courtesy of Peggy, formerly with the Green Apple Pie in downtown Seattle. Kids got free balloons and could enjoy a ride on the merry-go-round; leis and something called Hawaiian Freeze Pies enhanced the feeling of being on the islands. A 1971 fire seriously damaged the Hut, and it apparently did not reopen.

Palestine-born Saleh Joudeh arrived in Seattle by way of Italy in 1974, beginning his culinary career as a burger flipper at the nearby Green Lake Bowling Alley. A few years later, he took over a restaurant in the U District and renamed it Avenue 52. After a slow start, Saleh’s cooking began to garner rave reviews from local restaurant critics. In 1982, with his lease at Avenue 52 expiring, he moved to Green Lake and created Saleh al Lago (Saleh on the Lake). It is said that, at a time when most Seattleites’ concept of Italian food extended about as far as pizza, lasagna or spaghetti and meatballs, he introduced them to risotto, calamari and other classics of Italian cuisine. It was a sad day for Saleh’s regular clientele in 1999 when he was forced to close due to health issues.

At the north end of the lake was William Bryan’s restaurant, built in 1947 and originally called Bryan’s Fine Foods. By 1956, the restaurant had been renamed Bryan’s Lake Terrace Dining Room and made its mark on Seattle’s fine dining scene, featuring the freshest of seafood and steaks. Holiday dinners (turkey or prime rib) were long a tradition at Bryan’s, and reservations were a must-have on weekends. Bryan sold his restaurant in about 1960, but the new owners kept the name for a number of years. Bryan’s was located at 7850 N Green Lake Way.

MAGNOLIA

Northwest-bound out of downtown Seattle, Elliott Avenue runs along the bay for two and a half miles before turning north and becoming Fifteenth Avenue W on its way to Ballard. Just at the curve, the Magnolia Bridge carries traffic over railroad lines and port facilities up onto Magnolia Bluff and its small but prosperous business district, Magnolia Village. A couple of lunch counters were located here (the Magnolia Food Shop and the Magnolia Bowl Snack Bar, at 3212 and 3316 W McGraw, respectively), as well as a more upscale restaurant called Tenney’s. Verl and Alma Tenney, the owners and cooks, were well known for their homemade pies baked fresh daily: French apple, wild blackberry, pumpkin and pecan, among other flavors. By 1968, Tenney’s had become GG’s Restaurant, under management of Don and Clara Aust. Today, it’s an Austrian-themed steakhouse called Szmania’s. Tenney’s was located at 3321 McGraw. A few feet away at 3420 McGraw, and open as early as 1947, was the Village Grill, offering “good home cooking at moderate prices.” Still in business in 1960, it has since been replaced by a Chinese restaurant.

INTERBAY

Back on Fifteenth Avenue W, literally in the shadow of the Magnolia Bridge, in 1931 appeared what was billed as “a new concept in marketing”: the Mid-City Market, Seattle’s first drive-up shopping center. Today the idea of a supermarket or other large stand-alone store providing its own parking lot is taken for granted, but at the time, it was a revolutionary concept just beginning to become popular in California; until then, store patrons usually had to contend for street parking spaces in congested business areas. Under a single roof, with plenty of free parking, the Mid-City Market was home to a grocery store, meat market, dairy store, fruits and vegetables, even a service station—and Mrs. Helen Lea’s Mid-City Lunch restaurant. The Mid-City Lunch changed its name several times across the years and for awhile had a neighboring restaurant, the Cove Inn; both of them were still in business into the 1940s. (The Mid-City Market building still stands, though heavily modified, as the Builders Hardware and Supply Company.)

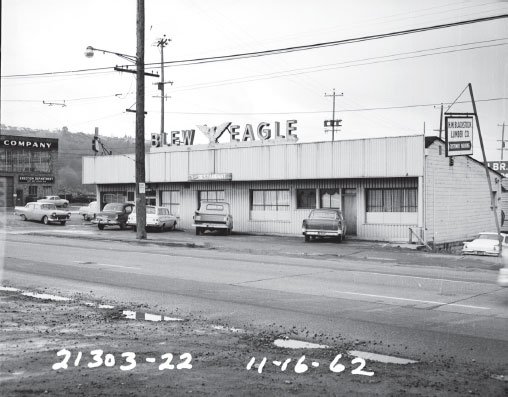

The M&J was a little storefront place, one of several along Fifteenth Avenue that catered to workers at nearby industrial operations. Seattle Municipal Archives, 65936.

Just north of the Mid-City Market were the Terminal Cafe and the Stewardess Cafe, facing each other across Fifteenth Avenue at 1601 and 1606 and marking the start of the industrial Interbay district with its massive railroad and shipping facilities. The appropriately named Interbay Cafe stood at 3053 Fifteenth Avenue; a few hundred yards north on the corner with Dravus Street was Hansen’s Café, and at 3204 was the M&J Cafe, typical storefront, short-order places catering to workers at the rail yard. The Fisherman’s Cafe, farther along on Fifteenth at the junction with Emerson Street, drew its customers from nearby Fisherman’s Terminal, home to hundreds of fishing boats and other watercraft.

BALLARD

Incorporated in 1890, Ballard’s early economy was based on sawmills and shingle factories and its access to open water (it sits on the north edge of Salmon Bay). By the time its citizens voted to be annexed by Seattle in 1906, Ballard had become a bustling town with a business district stretching along Ballard Avenue and a few side streets. Completion of the Ballard Bridge in 1917 brought Fifteenth Avenue across the Lake Washington Ship Canal about a quarter of a mile east of the original downtown; access from Fifteenth Avenue and the bridge to Ballard Avenue became more difficult after the bridge opened, and Market Street eventually developed into Ballard’s new downtown commercial district.

Ballard’s 1890 eating establishments included the Queen City Restaurant and Chop House and restaurants run by Burden & Linder, L.P. Levasseur, Carrie Rolff and Elizabeth McDonough. The Queen City Restaurant was still serving a decade later and had been joined by the Ballard Oyster House and the Home Restaurant. They had all disappeared by 1910.

One longtime resident of Ballard Avenue was the Owl Cafe & Tavern. The Owl opened as a saloon in 1904 and over the years was known by several different labels—saloon, café, tavern—and sometimes straddled the fine line of the law. In 1935, owner Emil Einess, aware of an impending police raid to seize his slot machines, called the department and told them not to bother—thieves had broken in the night before and stolen them. The Owl was still going strong in the 1980s as a bar with live music but had disappeared in the next decade after nearly one hundred years in business. The building that housed the Owl still stands, remodeled but basically intact, at 5140 Ballard Avenue.

Hattie’s Hat, another longtime survivor at 5231 Ballard Way, is the latest in a string of restaurants to occupy those premises. As early as 1924, Harry Pettyjohn was running a soft drink–lunch counter there. The Old Home Restaurant, under Bror Johnson and (later) Carl Anderson, was a longtime tenant. By 1955, it had become Malmen’s Fine Food, owned by Gus Malmberg, open twenty-four hours a day with cocktail service and “the mellow old Scandinavian flavor that made it a rendezvous for gourmet.” In 1971, Hattie’s moved in along with Aunt Harriet’s Room, the cocktail lounge. Forty-plus years later, Hattie’s remains Ballard’s favorite funky old-time restaurant. “Malmen” is still spelled out in small tiles on Hattie’s threshold.

In the early 1940s, Albert VanSanten had a restaurant at 5429 Ballard Avenue called the Vasa Sea Grill. (Vasa is Swedish for “ship.”) By 1952, a cocktail lounge, the Patio Room, had been added, and Francis King had been taken on as a business partner. King, the leader of a café orchestra in Seattle’s early days, played the violin in the restaurant until his death in 1956. The Vasa was another smorgasbord place—they called their version a Vasabord, available every Friday and Saturday evening from 5:00 until 9:00 p.m. and daily for lunch. The Vasa was still in business in 1979; today, the building is occupied by the Peoples Pub, a German restaurant.

The Home of the Green Apple Pie was located at 521 Pike Street. It’s unclear why a red apple, rather than green, was featured on the menu cover. MOHAI, 2009.86.1.

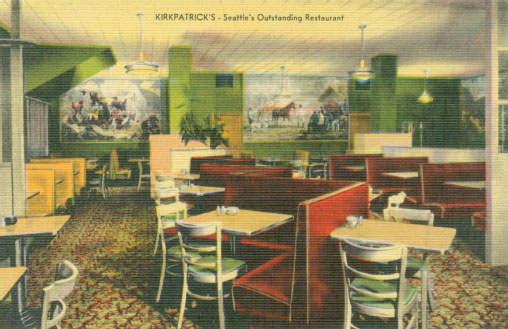

Earl Kirkpatrick was involved in many Seattle restaurants over the years. His biggest achievement was Kirkpatrick’s, at 416 Union Street.

The Georgian Room in the Olympic Hotel issued a series of colorful menus featuring idealized scenes from eighteenth-century royal courts.

Maison Blanc was housed in an elegant 1880s mansion with another restaurant, the Rathskellar, in a basement building fronting Marion Street. In the upper-left corner is a vignette of owner and chef Charles Joseph Blanc. MOHAI, 2009.71.

The Paul Bunyan Room was a 1960s addition to Frederick & Nelson’s food service, with Paul and his famous blue ox, Babe, portrayed on the menu cover. MOHAI, 1993.43_ box4_folder19.

Frederick & Nelson’s Tea Room served much more than just tea, as the cover of this seafood menu illustrates. MOHAI, 2009.86.

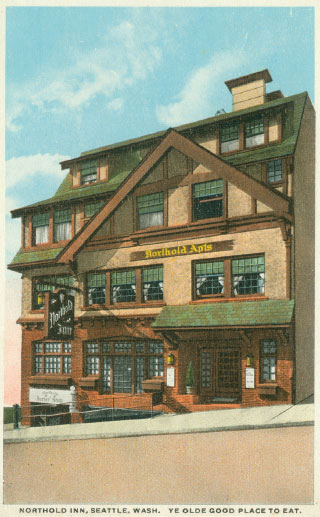

Claire Colegrove’s Northold Inn exuded the ambience of a Tudorstyle English inn with its half-timbered façade, dark woodwork and polished copper ornaments.

The layout of the Purple Pup, another Colegrove restaurant, was typical of its time: long and narrow with a counter and stools and booths lining the opposite wall.

This Triple XXX menu dates to the early 1920s—it lists Triple XXX cola (a short-lived product) along with the company’s mainstay root beer.

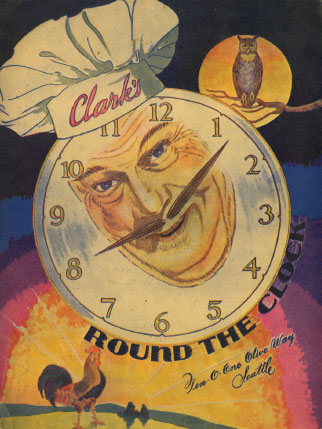

Day or night, Clark’s Round the Clock was always open at 1001 Olive Way. MOHAI, 1986.15.7.

A giant smiling fish served as a backdrop on Crawford’s colorful menu. Located right at water’s edge, Crawford’s guests had a great view of ship traffic on Elliott Bay.

The Norselander, on the top floor of the Norway Center, featured an elegant dining room with cloth-covered tables and a high-level view of Elliott Bay.

Skipper’s Galley played up the nautical theme. The restaurant was boat-shaped, and patrons walked a gangplank to get aboard.

The Wharf was two restaurants in one: the upscale dining room seen here and a workingman’s café adjacent, both served from the same kitchen.

Moored in Lake Washington aboard an old ferry boat, the Golden Anchors was accessible off beautiful Lake Washington Boulevard. MOHAI, 1996.30.3.3.

The interior of Manning’s, at the corner of Fifteenth and Market Street in Ballard, was the epitome of Googie-style coffee shop architecture in Seattle.

Carl Broome’s menu cover fittingly depicted a broom. This menu dates to the 1940s, after Broome had closed his Wallingford location. MOHAI, 2014.3.1.2.

The Coon Chicken Inn, on Bothell Way, was one of a chain of three, the others (also pictured here) being in Salt Lake City and Portland.

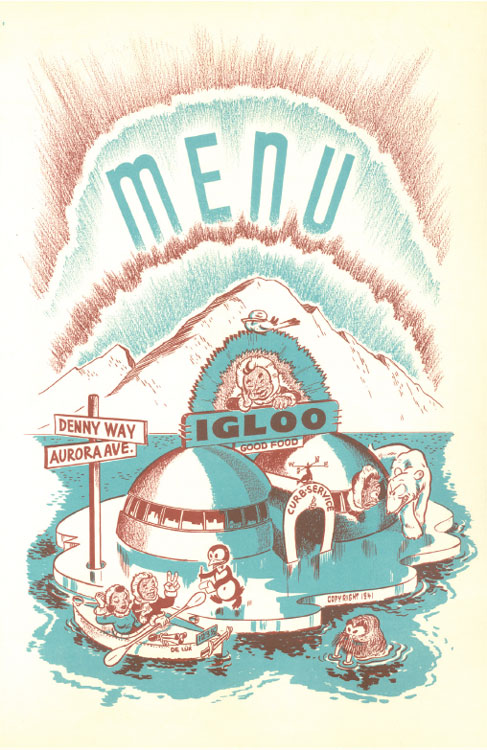

The Igloo floats on an icy island on this menu cover. A penguin takes an order from a drive-up boat while a polar bear roams the parking lot.

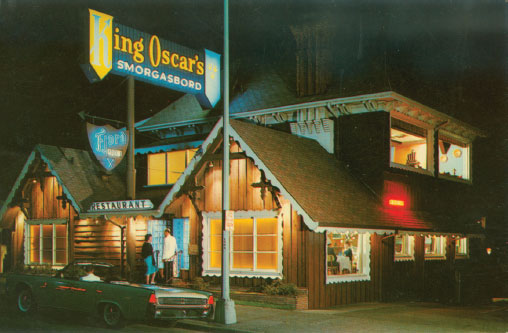

A well-dressed couple—she in furs, he in a tux—enters the warm glow of King Oscar’s on Aurora Avenue in this period postcard.

A pirate—looking the worse for wear—graces the menu cover of the Jolly Roger, a roadhouse on Bothell Way. UW, MEN036.

The cowboy-themed Bar-B-Q Chuck Wagon was also on Aurora, just north of King Oscar’s but a world away cuisine-wise.

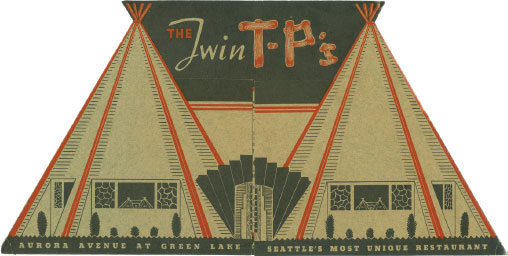

In later years, when Power’s Pancake Palace took over the Twin T-P’s, the gleaming steel teepees were painted orange and blue.

With a lovely señorita on the front and a dashing caballero on the back of its menu, Cook’s Tamale Grotto played up its Spanish essence.

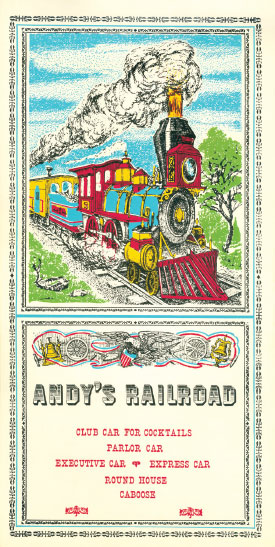

Andy’s Diner, housed in a set of repurposed passenger cars on Fourth Avenue South, took the railroad motif to the max with swizzle sticks shaped like train-crossing signs and paper engineers’ caps for the kids.

Once the crown jewel of Seattle’s roadside architecture, the Twin T-P’s opened in 1937 on Aurora Avenue (Highway 99) across from Green Lake.

Bob’s Chile repeated the Spanish theme a few years later, but this time the couple—slightly stylized—were dancing together on the menu cover. MOHAI, 1986.15.93.

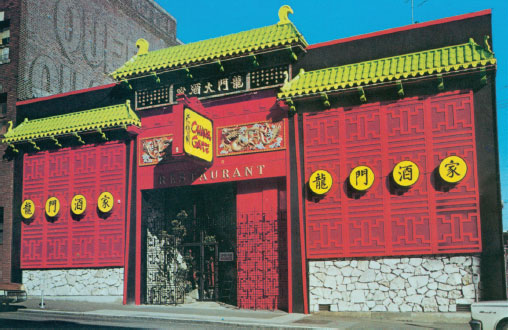

The imposing façade of the Gim Ling Restaurant (later the China Gate) loomed over Seventh Avenue South.

Trader Vic’s Outrigger in the Benjamin Franklin Hotel offered a colorful menu depicting idealized South Pacific scenes.

The China Pheasant was a dine-and-dance roadhouse on Highway 99; its menu was half American, half Chinese food items.

Bamboo partitions, thatched canopies above the tables and hanging bunches of bananas created an exotic atmosphere at the Kalua Room, in the Windsor Hotel at Sixth Avenue and Pike Street.

Elsewhere along Ballard Avenue were Blossom’s Lunch (also called the Corner Cafe and Bob & Nancy’s Cafe) at 5133 and the Swedish Kitchen at 5203 Ballard. The Fern Cafe, 4833 Twentieth Avenue, was a block off Ballard Avenue toward the water. The Fern specialized in hot cakes and waffles and put up lunches for workers along Ballard’s waterfront; it called itself “the home of the best T-bone steaks in town”—only forty-five cents—but seems to have been in business for just a few years in the 1930s. As early as 1907, there was a restaurant at 5203 Ballard Avenue; by the 1950s, it was called the Swedish Kitchen. In contrast to the already-developing persona of Ballard as a Scandinavian stronghold, Thomas Chinn had his Chung Sun Cafe at 5133 Ballard Avenue, where the Sunset Tavern is today.

John Kenney opened the Driftwood Cafe around 1936 at 5416 Fifteenth Avenue, a short block south of Market Street. By this time, Market (originally called Broadway) had become the commercial district and was the main route connecting Ballard with the Wallingford and University Districts to the east. The restaurant’s name changed a few years later—it became the Driftwood Inn—and by 1959, it had relocated to 1442 Market, still adjacent to the busy Fifteenth Avenue–Market Street intersection. Its advertising urged customers to “follow the crowds to the Driftwood Inn” for chicken, steaks, oysters and fish and chips served with courteous service in a pleasant atmosphere. Under Art Saulness’s management, the Driftwood became a bit upscale, with charcoal-broiled steaks and a variety of seafood dishes; they also introduced Ballard to pasties, the meat-and-potato turnovers brought to America by immigrants from Cornwall, England. After thirty-five years in business, Art and Marjorie Saulness closed the Driftwood Inn in 1979. Both of its locations are now parking lots.

The entire staff took a break to have their photo taken in front of the Fern Cafe. Unfortunately, none of them are identified. Ballard Historical Society.

Summer 1947 saw Noble’s Chicken Dinner Inn open at 1718 Market Street, in the building now occupied by Don Willis Furniture. It became the Spud Nut Shop in 1951, “spudnut” being a potato-based doughnut sold by a chain of stores that originated in Salt Lake City in 1940 and grew to over three hundred stores (of which about thirty-five remain). In the 1950s, Mr. and Mrs. William Markham sold their Spud Nut Shop to Mr. and Mrs. G.B. Gore; it was gone by 1958.

On Twentieth Avenue, half a block north of Market, was the Plantation. Originally named Snyder’s Southern Food, its specialty was New Orleans French Creole cooking: marinated shrimp in remoulade sauce, Dungeness crab legs with cognac, poached halibut filet with lime-butter sauce and beef medallions with sauce Marchand de Vin. John Wilson was part owner; Willard Lillquist, the manager; Chef Barbara Sandoval studied haute cuisine for two years in Paris. The Plantation was still there in 1977; today, it’s the Golden City Chinese Restaurant. Another Creole-Cajun restaurant, Burk’s, was located a few blocks off Twenty-Second Avenue. Terry Burkhardt’s cooking was more rustic than fine French Creole, with emphasis on jambalayas, gumbos and étouffées. It closed in 2005.

Barbara Sandoval’s Crème de Cognac

Blanc mange base, or vanilla pudding to serve 4, prepared according to recipe except minus ⅓ cup of the milk

⅓ cup fine cognac, or 1 part Grand Marnier to 1 part fine cognac to equal ⅓ cup ¾ cup whipping cream, whipped

Shaved almonds

Cook blanc mange or pudding to thickened stage. Remove from heat. Stir in cognac or combination of cognac and Grand Marnier. Cool. Fold whipped cream into cooled pudding. Serve in 5-ounce brandy snifters with shaved almonds on top. Yield: 4 servings.

Farther along on Market Street was a cluster of short-order lunch counter places: the Hasty Tasty Snak Bar, at 5401 Twentieth Avenue just south of Market; Matt’s Hamburger, 2213 Market Street; Power’s Fountain Lunch, 2216 Market; and the Royal Cafe, 2307 Market, which in 1936 offered lunch for twenty-five cents and Sunday dinner for only forty-nine cents. The Roxy Cafe, at 2023 Market, went through several name changes over the years. Oliver Cummings was running a café at that address as early as 1934. At some point, it was called the Sunshine Dairy Lunch; by 1951, it had become the Chef Cafe. A trio of Southeast Asian restaurants now occupy the premises.

The Cream Inn Cafe appeared at 2311 Market Street in about 1940. It was owned by Folle and Hanna Pihl and is now a cocktail lounge called Hazlewood. The building next door at 2319 Market has a long restaurant history. As early as 1918, Lena Foster was running a restaurant at that spot. The building did a stint as a Dunlap Radio store until Albert VanSanten (later of the Vasa Sea Grill) opened an eatery there. Albert Selleck bought out VanSanten and ran Selleck’s Cafe there during World War II. By 1946, it had become Gunnar’s Cafe, owned by Bennet Blumlo; Elbert and Veronica Cope took over in 1957 and operated Gunnar’s for another ten years until they retired. Heavily remodeled, the building has been home to one of the Azteca Mexican restaurant chain’s locations for nearly thirty years.

At the western edge of downtown Ballard were Matt’s Cafe at 2409 Market (now Hamburger Harry’s) and Andy’s Cafe across the street at 2442 Market; Andy’s became Smitty’s when Chester Smith ran it in the 1950s. A quarter mile farther west, where Seaview Avenue curves north toward Shilshole Bay, the Totem House served up fish and chips. Somewhat modified (and with an expanded menu), it’s part of the local Red Mill Burgers chain. Across the street and of more recent vintage, Hiram’s at the Locks was an excellent place for steaks and seafood with a great view of boat traffic through the Ballard Locks. Hiram’s arrived in 1976, underwent a name change to the Pescatore Fish Café, reverted back to Hiram’s and finally closed in 2003.

A totem pole looms large over the Totem House, at the west edge of Ballard, in this 1955 photo. Seattle Public Library, spl_wl_res_00139.

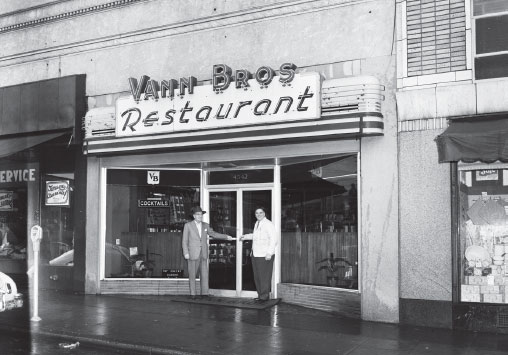

King Eddie’s Dina Buffet soon after it opened in 1954. It’s likely the man walking through the door is the king himself, Ed Davis. Seattle Municipal Archives, 78527.

On the east edge of Ballard, at the corner of Eighth Avenue where Market Street makes the long climb up Phinney Ridge, Ed Davis had a restaurant he modestly named King Eddie’s Dina Buffet. Ed was already known in Ballard for “the biggest hamburger in the world” and excellent steaks at the Davis Cafe, his place on Twenty-Fourth Avenue and Sixty-Seventh Street. In January 1954, the Seattle Times announced the opening of King Eddie’s “new eating establishment at 8th NW and Market Street.…Food that is fit for a king, queen, prince and princess will be ready day and night. Whether it is a steak or a snack, a dinner or a donut, King Eddie promises supremacy in service for 24 hours every day.” The new place was decorated “with the Mother Goose type caricatures of royalty,” and the house specialty was potpies. The King’s empire didn’t last long; it was apparently gone within a few years, and today, the Ballard Mandarin Chinese Restaurant occupies the former castle.

Back on Fifteenth Avenue, restaurants lined the street from the Ballard Bridge all the way to Sixty-Fifth Street, nearly a mile north. Just across the bridge, across from still-surviving Mike’s Chili Parlor, stood Peters’ Chanticleer at 4700 Fifteenth Avenue. Franklin and Ade Peters operated the Chanticleer for over twenty years before selling out in 1961 to Joe and Sharon Neyman. Originally from Butte, Montana, where pasties were (and still are) a popular lunch item, the Neymans possibly took a hint from the nearby Driftwood Inn and began making and selling pasties in their small café.

On the northwest corner of the Fifteenth Avenue–Market Street intersection stood one of the most distinctive pieces of roadside architecture in Seattle: Manning’s Cafeteria, part of the Manning’s chain of coffee houses, though the only one done in what is called the Googie style. Googie architecture originated in Southern California in the late 1940s (the name comes from a now-gone coffee shop in West Hollywood), and by the 1960s, Googie-style restaurants could be found throughout the country. Stylistic elements included upswept roofs, curved and sharply angled shapes and lots of glass and neon. The Manning’s building, designed by Bay-area architect Clarence Mayhew, was constructed in 1964. Sited where it was, at Ballard’s busiest intersection, it served as something of a greeting and gateway for residents and visitors. Manning’s operated from 1964 to 1983, served good food at affordable prices and became a gathering place for neighborhood regulars. After renovation in 1984, it reopened as a Denny’s. The doors closed in 2007, and despite vigorous opposition from preservationists, the building was demolished in 2008.

North on Fifteenth were the Three Sisters Cafe, the Red Robin Cafe and Fifteenth Avenue Fish & Chips. The Three Sisters Cafe, at 5912 Fifteenth, was earlier known as Liden’s Sandwich Shop. It later became an antiques store and today is the site of a Taco Bell. The Red Robin Cafe (not to be confused with the later Red Robin Gourmet Burgers chain) was located at 6117 Fifteenth Avenue in 1951. Fifteenth Avenue Fish & Chips, at 6409 Fifteenth where the street makes a slight jog on its way to Crown Hill, apparently didn’t last long, even with nearby Ballard High School as a potential customer base.

Leary Way, the connecting link between Ballard and Fremont, hosted a number of restaurants over the years: the Chat ’n Chew, just east of Ballard at 1440 Leary Way; the Cottage Cafe (also known as the Little Place), 3624 Leary Way, now home to Alberona’s Pizza & Pasta; the Cornell Cafe, 4302 Leary, where a hamburger stand was operating as early as 1939 and lasted until 1971; Birdie’s Cafe (later the Double VV Cafe), an “industrial lunch room” owned by Emma Tuckey in 1940, 4358 Leary; and Bergin’s Lunch at 5242 Leary—in 1973, it was the D&W, and today it’s the Señor Moose Café.

CROWN HILL

The Crown Hill neighborhood is centered on Fifteenth Avenue and Eighty-Fifth Street, another busy intersection of connecting arterials. In the 1930s, a small business district grew up around the intersection, of which a few buildings remain today.

A bit south of the intersection, at 8037 Fifteenth, was a place called the Twin Chestnuts. In 1946, owner Lawrence Simpier was robbed by a guntoting man wearing a child’s pink bandana for a mask. Kitchen worker Roy Parker tried to hit the robber with a glass of malted milk but missed and was shot at; luckily, he was only slightly injured. In the 1960s, it became McGrath’s Twin Chestnuts, open for luncheon and dinner only with “moderately priced home-cooked foods.” These days it is the Original Pancake House, an offshoot of the original Original Pancake House in Portland, Oregon.

At 8332 Fifteenth Avenue was Higgse Ice Cream Lunch, a hamburger shop–soda fountain place that vanished in the early 1950s. Next up were the Crown Hill Lunch and Christian’s, across the street from each other at 8505 and 8506 Fifteenth, respectively. The Fiesta Cafe, a dine-and-dance place owned by Peter Desimone, went in at 8517 Fifteenth shortly after the repeal of Prohibition; by the 1960s, it was a live music bar called Mr. P’s, and today it’s Centerfolds, an adult entertainment club.

The Harvester Restaurant began as the Brill & Spalding Tavern. In the 1960s, the Harvester advertised “delicious steaks, chicken, seafood served in pleasant neighborhood atmosphere” with cocktails in the Trophy Room. The restaurant suffered $200,000 worth of fire damage in 1979 due to faulty wiring of a stove hood and didn’t rebuild. Its site is now in the Value Village parking lot.

Another early place was Johnnie’s Hamburgers, 8521 Fifteenth. It’s mentioned in 1939 when it was held up at 2:15 one morning by two armed men—one with a gun, the other a knife—who ordered burgers and, when served, pointed a gun and robbed the cash register of about thirty-five dollars. It later became Johnnie’s Char Broiler, open twenty-four hours a day except Sunday, featuring rib-eye steak and eggs cooked the way you like them. Now it’s the parking lot of a Pizza Hut.

George Louie’s, possibly Seattle’s most far-flung Chinese restaurant in its day, opened in 1955 just off Fifteenth Avenue at 1471 Eighty-Fifth Street. In later days, George’s wife, Rose, recalled the locals being unfamiliar with Chinese food and that the Louies had to introduce them to this different, new cuisine:

When we first opened, people—the only Chinese food they are used to or knew about or would even bother to eat would be fried rice, chow mein, noodles, things like that. But gradually we expanded and included spicy dishes and more ethnic dishes. And people at first were skeptical, but they tried it and liked it. So we kept adding to it.

North of the Fifteenth–Eighty-Fifth intersection, Fifteenth Avenue becomes Holman Road and curves northeast to meet up with Greenwood Avenue. At the curve were three more eateries: the Coffee-Up Restaurant, at 9016 Holman; Little Acorn Cafe at 9053 Holman; and a different Crown Hill Lunch at 9081 Holman. They are all long gone.

LAKE UNION/FAIRVIEW

Fairview Avenue runs from the north edge of downtown Seattle to Lake Union through an area that, back in the day, was a zone of warehouses and light industry with a few scattered residences. Consequently, the restaurants were oriented to the working class. They included the Fairway Lunch Counter at 204 Fairview; the Fairview Cafe, owned by Blodwen “Bobbie” Blomquist on the corner of Fairview and Mercer; and Messmerized Chicken ’N Chips, 609 Fairview. The Little White Kitchen was in business under Victoria Bourgault’s management as early as 1933 at 713 Fairview. Next door and twenty years later, Modesto and Joseph Colasurdo had their M&J Cafe; it later became the B&A Cafe and went out of business in 1976. To the northeast, where Fairview merges with Eastlake after a short run along Lake Union, was the Lake Union Cafe (the original, not the same-named place a mile to the north these days).

EASTLAKE

A route of the early Pacific Highway, Eastlake Avenue was a major thoroughfare into and out of Seattle. Northbound from downtown, the highway passed through several distinct neighborhoods—Eastlake, the University District and Roosevelt—before turning northeast onto Bothell Way (Lake City Way today) and eventually to Everett and points north.

There were a few small cafés along Eastlake near its junction with Fairview. A lunch room at 1206 Eastlake, opened in the 1920s, became the Baum Cafe under Hazel Baum’s ownership. Just up the street was the New Shamrock Cafe, another early lunch place that lasted into the 1950s.

Another complicated thread of Seattle restaurant history: in the late 1940s, Les Teagle opened a restaurant at 304 Eastlake Avenue. Around 1955, he sold it to Harold Frye and found a new spot along Aurora Avenue. Frye renamed the Eastlake Avenue location, calling it Harold Frye’s Charcoal Broiler, and happily served lunch and dinner (and cocktails in the Sage’n Sand Room) until 1960, when it was taken by freeway construction.

Undeterred, Frye found a waterfront location on Lake Union at 2501 Fairview and opened Harold’s Satellite (the “satellite” moniker was chosen in keeping with the space theme of the upcoming Expo 21 fair). On the menu were seafood kabobs, lobster tails, salmon steaks and other seafood specialties, along with the usual steaks and prime rib. Unfortunately, Frye didn’t prosper in the new location; the Satellite closed after about two years, though Frye went on to open yet another restaurant in North Seattle. The vacant Satellite was purchased by Roy Myers, previous owner of the Richelieu Cafe in downtown, and renamed the Riviera. In 1969, it became the Hungry Turtle and was later known as the Landing.

On a slight rise overlooking the University Bridge, just off Eastlake at 3272 Fuhrman Avenue, was the first restaurant in the chain of Red Robin Gourmet Burgers. The story is told that its history began with Sam’s Tavern in the 1940s. Sam, the owner, sang in a barbershop quartet, and one of his favorite songs was “When the Red, Red Robin (Comes Bob, Bob, Bobbin’ Along).” He liked it so much that he changed the tavern’s name to Sam’s Red Robin. While it makes for a good yarn, it doesn’t appear to be accurate. As early as 1930, the Bridge Cafe—it later became Bee’s Corner Cafe—was at this address, and a 1942 classified ad announced that Tommy Dace, well known in local musical circles, “must sell the Red Robin, 3272 Fuhrman Avenue.”

Whatever the facts, it’s certain that Red Robin was a well-established name by the time Gerry Kingen purchased it in 1969. A newspaper comment of the day captures the Red Robin’s early ambience: “very old-tavernish; loud jukebox, a line of hunched shoulders and long hair at the bar; at the tables a mix of old-timers and college kids just discovering the place,” with the scent of marijuana detectable, particularly on the open balcony that overlooked the Ship Canal.

Bee’s Corner Cafe occupied 3272 Fuhrman long before the first in the Red Robin chain took over in the late 1960s. Washington State Archives Puget Sound Regional Branch.

It wasn’t until the mid-1970s that Kingen started to serve hamburgers—at first only the usual varieties, but eventually offering twenty-eight different types of burgers—and the place exploded in popularity. Kingen began selling Red Robin franchises; a second Red Robin opened in Yakima in 1979 and another in Portland the following year. By 1985, the Red Robin chain included 175 restaurants and corporate headquarters were moved to Irvine, California. Today, the total number of Red Robins worldwide tops out at over 500 locations.

The first Red Robin, progenitor of the chain, as it looked circa 1970. Washington State Archives Puget Sound Regional Branch.

While all this explosive growth was happening, the original Red Robin in Seattle continued dishing out burgers to a steady clientele—until the corporation decided that the building was too out-of-date and not worth rehabilitating. It closed in 2010, and the building was removed.

UNIVERSITY DISTRICT

Eastlake Avenue becomes Roosevelt Way after crossing the University Bridge. Half a mile to the east is the University of Washington (UW) and the aptly named University District. When the UW relocated from downtown Seattle to take advantage of buildings left by the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, this lightly populated area was known as Brooklyn. It didn’t take long for the university to bring explosive growth to the neighborhood.

In short order, a mile-long business district of restaurants, clothing stores and movie theaters had sprung up along Fourteenth Avenue (soon to be renamed University Way, commonly called the Ave) to service students and faculty. Dozens of cafés and lunch counters fed hungry students on the run between classes. A few fine dining places intermingled with the cafés, and two hotels anchored the northern end of the district.

At the southern end of the district were such places as the Portage Bay Grill, the Snack Shop, the U&I Cafe and the Club Cafe. At 4136 University Way was an outlet for a small local chain called Fabulous Burgers, which had five other locations around the city. In 1953, fifty cents would buy “two of the most fabulous hamburgers you ever ate”—quarter-pound hamburgers, each on a large bun with onions, lettuce, tomatoes and a thick slice of Tillamook cheese. Howard’s Restaurant was a typical storefront eatery at the corner of Forty-Second and the Ave. Just up the street were Opal’s Grill and Harvey’s Kitchen.

Among the earliest eateries was the Olympia Cafe at 4003 University Way, in business since at least 1932 with frosted refrigerator pipes spelling out the café’s name in the front window and an old-fashioned “Booths for Ladies Only” sign on the door. Longtime owners George Apostolou and John Soldano were legendary for feeding hungry and sometimes penniless students; noted architect Victor Steinbrueck recalled that, when he was a student, “George and John always made certain we had plenty to eat, really loaded us up on mashed potatoes and gravy, plus big portions of meat and crusty bread—stuff that really stuck to your ribs.” The price? Thirty-five cents. Steinbrueck remembered the Olympic as “real, not synthetic—something difficult to find these days,” but even in 1965, it was one of the last remnants of an earlier generation of restaurants. The Olympic was the last restaurant on the Ave to sell meal ticket books.

Howard’s was one of several dozen restaurants along University Avenue catering to students and faculty from the nearby University of Washington. University of Washington Special Collections, SEA3554.

The greatest concentration of restaurants on the Ave was along the twoblock stretch between Forty-Third and Forty-Fifth Streets. The Columns Cafe was at 4302; opened in the late 1940s, it was gone by 1965. Next door was a hamburger stand called Rod & Dean’s. The Lun Ting Cafe, at 4318 University, featured barbecued spareribs, egg rolls, won ton soup and almond chicken and was open only for dinner. Near the busy intersection with Forty-Fifth Street was a group of fountain lunches: Leo’s Fountain Cafe at 4342 University, Norm’s Fountain at 4344 (now occupied by Bartell Drugs, which had its own fountain service) and Graham’s Restaurant & Fountain at 4701 University Way.

Farther along the Ave as it headed toward the Ravenna neighborhood, Hasty Tasty Cafe (5247 University) was a favorite for hamburgers and milkshakes. By 1980, it had become Avenue 52, a restaurant that combined Syrian and Italian cuisine. On the menu were fettuccine, chicken Bolognese and other Italian dishes, along with Syrian specialties such as shish kabob and “upside down” chicken (layers of boneless chicken, deep-fried cauliflower and seasoned rice). Avenue 52 closed when owner Saleh Joudeh moved to Green Lake to open Saleh al Lago.

Among the fine dining spots on the Ave were Lee’s Broiler and the Robin Hood Grill. Lee’s, at 4553 University, occupied a spot previously home to Sandy’s Grill. In 1956, a seven-course steak dinner cost $2.15; the sauerbraten dinner was $1.55. Lee’s was open for lunch and dinner, “a continental flavor in an intimate modern atmosphere,” with original broiled specialties served Oriental style. When the state legislature changed the zoning for the U District from dry to wet in 1967, Lee’s was the first restaurant on the Ave to be granted a liquor license. Still in business in the mid-1980s, today a Starbucks fills the space where Lee’s was.

The restaurant at 4334 University had several names over the years. As early as 1923, A.G. Wilds and Roy Hosfield were running the Al Roy Restaurant there. In the 1940s, it was Dick Wiseman’s; a few years later, it was Ken’s Hamburger Shop. It went upscale in the mid-1950s as Cherberg’s Chimes and, later yet, the Robin Hood Grill, with a menu of steaks and entrées (five different types of steaks along with pork chops, veal cutlets, beef liver and bacon and spaghetti); sandwiches, including the house specialty Robin Hood’s De Luxe Hamburger (lettuce, tomato, mayo, olives on a toasted bun) and clubhouse, minced ham, chicken salad and grilled chicken sandwiches; breakfast; and full fountain service with sundaes, milkshakes and soft drinks.

In 1923, an elegant apartment hotel, the Wilsonian, opened at the corner of University Way and Forty-Seventh Street. The seven-story brick and terra-cotta structure offered ninety-nine rooms of various levels of luxury aimed at attracting both long-term residents (many of them on the faculty of the university) and overnight guests. Helen Swope of tearoom fame managed the Wilsonian’s two dining rooms—the main room, the Peacock, and a smaller Italian-themed dining room called Via Fontana. Within a year, the Peacock Room—“its decorations and furnishings daring in the extreme, yet in compete harmony…a series of moderate-sized rooms afford privacy without the shut-in feeling of the ordinary restaurant dining room”—had become the social center of the University District and was a favorite destination for holiday dinners.

Helen Swope parted ways with the Wilsonian in 1931 to assume management of dining room services at the new Edmond Meany Hotel, located two blocks away at Forty-Fifth and Brooklyn. The Wilsonian’s Peacock and Via Fontana dining rooms became casualties of the Depression; the Wilsonian was sold in 1939, but a café continued operating there into the 1950s. The Edmond Meany is now known as the Hotel Deca; the Wilsonian still stands but is not in business as a hotel.

ROOSEVELT

In days prior to Highway 99 and Interstate 5, Roosevelt Way was a main thoroughfare for traffic northbound from Seattle toward Bothell and Everett. Just north of the University Bridge, a number of roadside cafés sprang up near the busy junction of Roosevelt and Forty-Fifth Street, the main arterial connecting the University District with Wallingford and Ballard to the west. Bess N’ Nita’s Tasty Nook was at 4109 Roosevelt in the 1950s. At 4228 Roosevelt was the Crab Spot, which later became Campos, operated by Danny and Abel Campos and billed in 1961 as “the only Texas-Mexican style restaurant in Seattle.” The Campos brothers learned the restaurant business from their father and had all his recipes, along with the spices and other ingredients “that makes Texas style different from other Mexican foods.” Chicken and guacamole tostadas were a specialty; décor included serapes on the walls and an Aztec sundial plate.

D-Lux Hamburger (later called Kirk’s Burgers) was located next to Campos. Up the street at 4526 Roosevelt was the Blue Moon Cafe (not to be confused with the nearby and still-extant Blue Moon Tavern). A few doors away was the Red Rooster Cafe; opened in 1939 and operated by Frankie France and Irene Ledwich, it later became Chester’s Cafe. Across the street was the Auto Row Cafe at 4551 Roosevelt Way, and two blocks farther north was the Nifty Nook, an eleven-stool restaurant later known as Goldie’s Cafe.

Several other eateries were scattered alongside Roosevelt Way as it continued north. For nearly twenty years, Greek immigrant Peter Anastos had Pete’s Barbecue at 5300 Roosevelt; it later became the Maple Inn and today functions as Dante’s Tavern. Two drive-ins, Ronken’s and the Hamburger Round-Up, were a few blocks north. By 1965, the Hamburger Round had become the Taj Mahal Restaurant. It was located at 6106 Roosevelt.

By the 1920s, a business district had risen at the intersection of Roosevelt and Sixty-Fifth Street, and locals and highway travelers had a number of restaurants to choose from. There were the Roosevelt Coffee Shop at 6417 Roosevelt Way and Lloyd’s Lunch at 6503 Roosevelt, in business as early as 1934 under H.J. Lane and lasting into the ’50s. Clement Arnold had the Rainbow Cafe at 6409 Roosevelt; it later became a Chinese restaurant called the Ming Garden. Another café-turned-Chinese-restaurant was at 6510 Roosevelt; first called the Hollywood Cafe, by the 1950s, it had transformed into the Far West Cafe. H.T. “Ted” Holmes ran De Luxe Hamburgers at 6603 Roosevelt; in addition to burgers, he was well known for his chili. By the mid-1940s, the thirty-nine-seat B-29 Cafe could be found at that address.

The district’s premier eatery, as well as one of the earliest, was located at 6521 Roosevelt, where a café was in business by the mid-1920s. By the next decade, it was known as the Wayfair Cafe, owned by Lynette Perry. Egyptian-born Abraham Nakla bought the place in 1947, remodeled it and reopened it as Abie’s Grill. “World famous chef Abie,” as he liked to describe himself in ads, specialized in $0.85 dinners with a choice of baked spareribs, steamed wieners with sauerkraut, grilled hamburger steak, minced ham omelet, grilled liver and bacon, Columbia River smelts, fried oysters, grilled salmon or halibut steak. Also on the menu were roast beef, pork, turkey, baked chicken, baked ham and a full-course steak dinner for $1.50. Abie’s was always open for breakfast—egg dishes, omelets, French wheat cakes and waffles.

In 1948, Abie sold his Roosevelt location and opened a new place just east of the University of Washington in the new Laurelhurst Shopping Center on E Forty-Fifth Street. A colorful character, Abie continued to offer full dinners at moderate prices until his passing in 1959. After Abie departed Roosevelt, the restaurant’s name reverted to the Wayfair Cafe, with “lots of good food at modest ‘family’ prices.” Fred and Pat Garski became involved in the restaurant, and by 1951, it had been renamed Garski’s Scarlet Tree. Remembered as “a relaxed, friendly atmosphere [that] provides the perfect setting for enjoyment of dinner, luncheon, cocktails or late evening suppers…a Northeast Seattle tradition,” the Scarlet Tree served up steaks, full-course dinners, luncheons and cocktails. Two-for dinners were a specialty; the menu offered a choice of regular full-course dinners starting at two for $5.90. Top of the line were steak and lobster dinners priced at two for $10.90 in 1974.

Just north of Sixty-Fifth Street, at 6815 Roosevelt, was the Marnex Drive-In. A Triple XXX Root Beer barrel originally occupied the spot but was torn down in 1940 when the owners chose to open a new Triple XXX on Bothell Way, half a mile north. The Marnex took over the site a few years later; initially a typical drive-in vending $0.19 hamburgers (five for $0.50 with special coupon), milkshakes for $0.19 and a side of french fries for $0.11, by the mid-1950s, the Marnex had evolved into a full-service restaurant with four different steak dinners—filet mignon, club steak, T-bone or ribeye—ranging in price from $1.00 to $1.65 and a “complete fountain and restaurant menu.” Renamed Bojack’s Restaurant by 1962, it suffered a major fire that year and apparently never reopened.

WALLINGFORD

Wallingford’s compact commercial center grew up astride the trolley line that once ran west along Forty-Fifth Street from the University District before turning south on Stone Way en route to downtown Seattle. Over the years, numerous restaurants intermingled with clothing shops, hardware stores and several movie theaters. At the west end near the Stone Way intersection were the Forty-Fifth Street Cafe (1224 N Forty-Fifth Street), the Wishbone Cafe (1304 N Forty-Fifth) and the Tip Top Sandwich Shop (1400 N Forty-Fifth).

At 1403 N Forty-Fifth Street was Broome’s Aristocratic Hamburger Shop, which had the dubious distinction of having been bombed twice in 1935 during a time of labor troubles. Owner Carl Broome rebuilt and within a few years opened two more shops, one on Queen Anne Avenue and another on Broadway. A few blocks farther east were the Chili Bowl Cafe at 1605 N Forty-Fifth and the Green Lantern Cafe and Gus’s Steak House at 1618 and 1624 N Forty-Fifth Street, respectively.