The Jolly Roger was an infamous roadhouse along old Highway 99 (Bothell Way) in northeast Seattle. Shoreline Historical Museum, 2028D.

Along the Highways

Modern highways were late to arrive in the Seattle area. Water, dense forests and mountains determined that the original inhabitants and earliest settlers primarily moved about by boat. Early roads were often no more than cow paths; muddy and impassable in the rainy season, they rarely led directly from one settlement to another. Road-building and maintenance were usually left to local jurisdictions.

In 1911, Washington State passed the Permanent Highway Act, which transferred more road building responsibility to the state and authorized the construction of hard-surface roads to enhance commercial transportation. In 1912, the Good Roads Association joined the effort to improve Washington highways and proposed three major truck routes in the state: the Sunset Highway, the Pacific Highway and the Inland Empire Highway. Seattle sat at the intersection of two of these major routes: the north–south Pacific Highway, which, when tied into same-named routes in Oregon and California, ran the entire length of the West Coast from the Canadian border to Mexico, and the east–west Sunset Highway between Seattle and Detroit.

Passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act in 1921 heavily involved the national government in highway planning and funding. Standards for highway construction were put in place. In 1925, the Bureau of Public Roads, predecessor to today’s Federal Highway Administration, approved a plan by the American Association of State Highway Officials to create a numbering system for national highways. Within a few years, highway names were replaced by numbers, which, if less romantic, were at least consistent. The Pacific Highway became Highway 99; the Sunset Highway was renamed Highway 10. (Today, Interstate 5 has succeeded Highway 99; the Highway 10’s modern replacement is Interstate 90.)

Major improvements to both highways in the 1920s led to more travel. Autos became affordable, people began traveling for recreation and tourism flourished. The Sunday drive in the country became a family tradition. Roadside businesses—restaurants and cafés, auto courts and motels, service stations and tourist attractions—sprang up to meet the wants of the new generation of motorists. And Seattle was primed for it: over the years, well over seven hundred traveler-oriented roadside businesses appeared along the major highways leading north, south and east out of downtown.

THE PACIFIC HIGHWAY HEADING NORTH

The Pacific Highway originally followed Eastlake Avenue from downtown Seattle to the University Bridge north on Roosevelt Avenue onto Bothell Way (today called Lake City Way). Just outside the town of Bothell, it swung north toward Everett on what was locally called the Everett-Bothell Highway. (For a few years, this route carried the Highway 99 designation but lost the title to the Seattle-Everett Highway soon after the latter’s completion in 1927.)

The Jolly Roger was an infamous roadhouse along old Highway 99 (Bothell Way) in northeast Seattle. Shoreline Historical Museum, 2028D.

Roadside businesses were quick to develop along the highway at Seattle’s northern limits, where residential development tended to be sparse. Among the most noteworthy was the Jolly Roger at 8721 Bothell Way. The pink stucco art deco building was a notorious place called the Chinese Castle from 1933 until 1935, when it was remodeled and reopened as the Jolly Roger. A dance hall and restaurant with a skull and crossbones flag flying from its tower, the Jolly Roger was popular for many years even though it had difficulty shedding its predecessor’s reputation. Declared a Seattle Historic Landmark in 1979, it was destroyed by arson in 1989.

Another famous, though controversial, landmark was the Coon Chicken Inn. It was one of a chain of three created by M.L. Graham, the others being in Salt Lake City and Portland. The Seattle restaurant opened in 1929 at 8500 Bothell Way and underwent several design changes over the years.

Not surprisingly, chicken was the featured item on the menu. The famous Coon Chicken dinner (one dollar) included a shrimp or fruit cocktail, chicken consommé, salad (fruit or lettuce and tomato), southern fried chicken, french fries, Parker House rolls, olives, vegetables, pickles, cranberry sherbet, choice of dessert and beverage. À la carte chicken (portions of a quarter, half or a whole chicken), chicken with noodles, fried chicken sandwiches and chicken pies; various types of sandwiches such as clubhouse, tuna, shrimp salad, baked or fried ham, pimiento ham and roast pork; hamburgers; and several varieties of salads rounded out the menu.

Attached to the main Coon Chicken building was Club Cotton, a nightclub that opened in February 1934 with great fanfare. As many as 250 people could be accommodated by the club. Dining, dancing and entertainment by the Club Cotton Merrymakers were offered on a nightly basis with no cover charge. A limited menu of food items from the inn was available at the club.

Club Cotton closed along with the Coon Chicken Inn in the 1950s, and both have long since disappeared. While it is understood that usage of the word “coon” in this context is racially insensitive, the Coon Chicken Inns were a significant part of the American roadside and cannot be overlooked. At the time, there were many restaurants that went by names such as Mammy’s Shack and other derogatory terms. In fact, Blake’s Mammy Shack, another southern-style chicken dinner place, was just a mile or two farther up the highway.

At one time, there were so many chicken places along this part of the Pacific Highway that local newspapers printed guides. There were the Check ’n’ Double Check, Rebel’s Inn, Lemm’s Corner and the Dixie Inn within a short distance of one another. And if the potentially derogatory implications weren’t already clear, there was Henry the Watermelon King—“Real Southern Watermelons Our Specialty.”

Not all was southern- (or chicken-) influenced, however. Several famous eateries as well as more conventional cafés and lunch counters lined the highway between Seattle’s city limits and Bothell. The Porterhouse Eagle Inn was well known for its porterhouse steaks and Friday seafood buffet. Another famous restaurant was the Plantation, open as early as 1926 and later known as the Green Parrot Inn, the Mountonian and the Manor. Chicken (of course) was on the menu, along with steak and trout dinners. Not far from the Jolly Roger was the wonderfully named Winnie Winkel’s Inn, about which little is known. The Wishbone Dinner House was along the highway at Kenmore. At 9824 Bothell Way, and only recently closed, was the Italian Spaghetti House and Pizzeria, a longtime favorite of North Seattleites.

HIGHWAY 99 NORTH VIA AURORA AVENUE

By the mid-1920s, the old Pacific Highway via Kenmore was falling out of favor as being too long and circuitous, and motorists were clamoring for a more convenient direct route between Seattle and Everett. Highway planners proposed a main road that would follow a nearly straight line south from Everett. Once in the city limits, the route would follow Aurora Avenue (then called Woodland Park Avenue) along the west side of Green Lake to a high bridge crossing over the Lake Union Ship Canal and skirt the east side of Queen Anne Hill into the central business district.

Most of the plan came true in 1927 when the Seattle-Everett Highway opened: a marvel of modern highway engineering with two paved lanes and two more (one each direction) reserved for future expansion if the need developed (which didn’t take long). But there was a problem—after twenty-five miles of straightaways, smooth curves and gentle grades, the highway suddenly terminated at Green Lake, three and a half miles north of downtown.

What stood in the way of completion was Woodland Park—ninety-one acres of greenery and open space the city had purchased from pioneer businessman Guy Phinney in 1899. Engineers called for cutting the new highway through the park, and in 1930, the Seattle City Council voted its approval. But vociferous objection, most notably by the Seattle Times, delayed construction for several years, and in the interim, vehicle traffic had to traverse several routes around Green Lake to avoid the park—for instance, following Green Lake Way to Stone Way, crossing the Fremont Bridge and taking Westlake Avenue into downtown. This wasn’t exactly the direct route drivers had been promised.

Construction finally happened 1932; the Aurora Avenue Speedway, as it was called, was built through the park, overlaying portions of West Green Lake Way and Linden Avenue at the north end. The Aurora Bridge (formal name: the George Washington Memorial Bridge) opened the same year, the last link of the highway to be completed, and Aurora Avenue (soon to be designated part of U.S. Highway 99) became the newest and fastest way to get into or out of the city from the north.

Suddenly the terminus of Aurora Avenue at Denny Way became a very busy place. What had been an area of mixed-use residences and open space now found itself home to businesses catering to the motor trade. No fewer than six service stations can be counted in a 1930s photo of the intersection.

Restaurants weren’t lacking either. Among the first to take advantage of the new highway was Bob Murray’s Dog House, originally located at 714 Denny between Aurora and Dexter Avenues. The Dog House opened in 1934 under co-owners Bob Murray and F.S. Knuppe. Born in Aberdeen, Scotland, Bob Murray managed several theaters—the Blue Mouse and Music Box—after arriving in Seattle. Described as a “prominent sports enthusiast,” he became involved in wrestling in 1936 as a promoter and match-arranger for the Western Athletic Club while continuing to operate the restaurant. Though Knuppe remained involved for several more years, the place rapidly became known as Bob Murray’s Dog House, a name it retained for nearly sixty years and under several different owners.

Murray relocated in 1954 when the Battery Street Tunnel was built through, or more correctly below, the Aurora/Denny intersection. The junction had been at street level, but the tunnel was some twenty feet below grade and involved construction access ramps between Aurora and Denny. Murray felt that the new alignments made it difficult for his customers, so he relocated the Dog House to 2230 Seventh Avenue, about a tenth of a mile away. The old location became Dick Odman’s Broiler, at least until 1971.

The Dog House was an immediate success from the day it opened. A 24/7 operation, it attracted a motley lot of customers and became famous for and took pride in its blue-collar, greasy spoon reputation—some of it deserved, some not. A mural behind the counter depicted its mascot pooch and doghouse and “All Roads Lead to the Dog House” slogan. The same themes were repeated on the menus, and for a time, the restaurant sponsored a baseball team called the Bowwows. In the cocktail lounge (stocked with “the usual booze”), organists played requests of show tunes and television theme songs and sometimes whistled their way through an entire set.

Former Seattle City Council member Jean Godden recalled:

“What’ll it be, honey?” was the phrase used by lippy apron-clad waitresses. The clientele was heavily blue collar: cops, musicians, night-shift workers, journalists, janitors, cabbies and serious writers looking for a slice of urban life.…The fare was basic, comforting and cheap, even by the standards of the times. One of the menus (probably dating from the 70s) shows Rib Steak (tenderness not guaranteed) with fries and a salad for $1.25. Also on the menu, Bob’s special burger—double super with onions and fries—55 cents. Then there was The Pooch—a hamburger that speaks for itself.

Seattle Times columnist Erik Lacitis wrote of a visit in 1984, when lunch specials were $3.50 and dinner specials $5.95:

I was finished with the salad. The waitress took the fork out of the bowl and placed it by my dinner plate. “You’ll be wanting to keep this,” she said. You bet that The Dog House is one of the original recyclers. Why give you two forks when one will do?

My baked potato came with butter. I asked the waitress if there was sour cream. “No,” she said. You bet that The Dog House is a direct kind of place.

Nobody challenges the authority of a Dog House waitress, average age about 50. It’d be like swearing at your mother.

A winsome pup graced the menu cover of Bob Murray’s Dog House on Denny Way. University of Washington Special Collections, MEN005.

But the food was good, he said:

On one recent visit, I tried the grilled fresh salmon steak ($6.50 for the special dinner). It was nice and moist and flaky. A few days before that I had paid twice that much for salmon cooked about the same, only served by a guy with an operatic Italian accent.

I’ve also tried the deep-fried Louisiana prawns, “served with our delicious barbecue sauce.” At $6.50, I got a plateful of prawns. So they weren’t sautéed in a delicate wine sauce. They were big and fresh and juicy. Some days you just feel like eating deep-fried stuff.

No matter what you order, a meal for two, including a couple of drinks from the bar, shouldn’t run more than $20. It’s not going be a dinner that’ll get raves in Gourmet magazine. But like the waitresses, it will be an honest meal.

The place even gained literary fame: mystery writer J.A. Jance used the Dog House as a locale for her protagonist, retired Seattle Police Department detective J.P. Beaumont.

After Bob Murray passed away in 1970 his wife, Petie—remarried to Bill Boudwin—operated the Dog House up to her own death in 1980. In later years, it was owned by Laurie Gulbransen, who started as a waitress in 1934, became manager in the 1940s and assumed ownership by the 1970s. The story was that the restaurant had been willed to her by Murray after his death.

When the Dog House closed in January 1994, it received eulogies befitting a famous personality, which by that time it had become. It was replaced by the Hurricane Café, itself now a victim of Seattle’s South Lake Union area urban growth.

At the Denny-Aurora intersection was the Carnival Drive-In. Next door, Ernie Hughes and Ralph Grossman opened the Igloo at 604 Denny Way in 1941. Self-described as the “most novel restaurant in the West,” it consisted of two igloo-shaped domes joined by an ice tunnel–like entryway between them, in keeping with the igloo theme. Above the twin domes was a neon sign flashing the restaurant’s name and the image of the smiling face of a fur-clad Eskimo with a rainbow on either side. At the time the Igloo opened, there were practically no other buildings around, and it must have been a spectacular sight that easily drew in travelers from Highway 99.

Inside, the Igloo offered booth and counter seating for ninety-six; outside was parking space for one hundred cars. Indoor waitresses wore white uniforms with blue-dotted aprons. Curb service was provided by waitresses who originally wore what was described as “mounted police uniforms,” though by the ’50s the uniforms had become the ubiquitous car-hop attire: short skirts, puffy blouses and tasseled cowgirl boots. A staff of as many as twenty-seven inside and outside workers might be on the job at any given time.

The Igloo threw a party for its second anniversary in June 1943. “All Seattle is invited to join in,” said its ad in the Seattle Times:

Two years ago we opened our doors for business…a novel drive-in dining spot that specialized in delicious food. Now, in spite of food rationing and restrictions, you still get fine food, well served in booth, counter or in your car. You’ll find, too, that we’ve grown during these past two years.…We don’t serve beer or wine…but we do have a splendid selection of fountain specials, as well as complete meals and short orders. You will enjoy the service of the courteous, beautiful and well-trained girls.…If you have not been one of those who have visited The Igloo…Mr. Ralph Grossman and Mr. Ernest Hughes and their staff would like to meet you and serve you.

A 1941 menu listed the usual short-order items and sandwiches plus the Igloo hamburger (toasted bun, cheese, relish, pickle, mayonnaise and lettuce for fifteen cents), the Husky hamburger (giant sized, with french fries for twenty-five cents) and the St. Bernard hot dog (with chili for twenty-five cents). A pounded farm steak (what we’d today call a chicken fried steak) with country gravy and fries cost fifty-five cents, while the Sea Shore Dinner (crab cocktail, scallops, salmon, filet of sole, oysters, fries and tartar sauce) would set you back sixty-five cents.

The Igloo served up a hearty breakfast and was especially proud of its fountain service. In addition to typical ice cream, sodas and sundaes, the Igloo featured several specialties, such as the Sun Valley Banana Split (three scoops of Danish chocolate, vanilla and strawberry ice cream), the Mt. Rainier Revel (Danish vanilla and chocolate, caramel-topped, with nuts and whipped cream) and the Mt. Baker Special (pineapple and orange sherbet topped with strawberries, crushed pineapple and whipped cream).

Irene Wilson, a waitress, recalled how busy the Igloo was in the 1940s: “I liked working outside better. More freedom. Outside, you only had to worry about your tray. Inside, they had to bus the tables.” She enjoyed her time at the Igloo and particularly the effort her boss Ralph Grossman put into creating a homelike atmosphere for the workers.

By 1954, the Igloo had been acquired by the local Sanders chain, and two running penguins had been added to the sign above the domes along with awnings above the windows. The Igloo was outside the construction zone of the new Battery Street Tunnel—a 1954 photo clearly shows it to be well away from the new off-ramp between Aurora and Denny—but for some reason both it and the Carnival disappeared at about that time.

North of Denny, Aurora remained largely residential for a number of years, though businesses gradually began moving in. My Pal Cafe at 410 Aurora was open by 1938; in 1960, it was owned by Mr. and Mrs. Lawrence Crane. At 421 Aurora, Emma Gordon operated a ten-stool, four-booth lunch room called the Green Hat Cafe as early as 1933. The restaurant at 702 Aurora went through probably more name changes than any other in Seattle—at least eight. From humble beginnings as the Aurora Tavern in 1934, it had become the Aurora Cafe by 1941. Between 1947 and 1951, it was Kirkpatrick’s Coach Inn, owned by Earl Kirkpatrick and managed by Glenn Vickers. Kirkpatrick sold the place in 1951, and the name changed to Sutherland’s Coach Inn, specializing in prime rib dinners with cocktails in the Tally Ho Room. Sold yet again and apparently completely remodeled, the restaurant reopened in 1954 as Taller’s Charcoal Broiler.

Taller’s took out a quarter-page ad in the Seattle Times to announce its grand opening with a menu featuring complete lunches and dinners, steaks, seafood, chicken, spaghetti and homemade pies. Thoughtfully, the owners provided a display window opening onto Aurora so that passing motorists could watch the charcoal broiler in action. By 1963, Taller’s had became the Hippopotamus Restaurant, run by Dick Komen and L.E. Kirkham, who also owned Bud’s Burger Haus at 2424 Aurora. In 1975, it was Murphy’s; two years later, it became La Mancha, operated by Richard C. Mancha and advertised as a Mexican smorgasbord featuring everybody’s favorite dish, menudo. The end came in 1980 when La Mancha quit business and all the restaurant equipment was auctioned off.

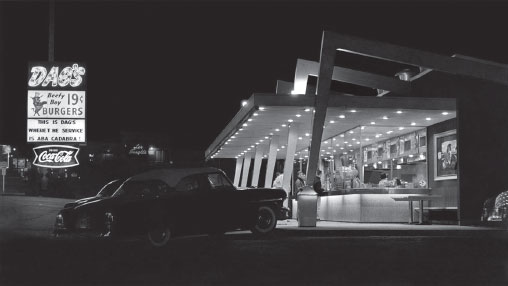

In the early 1950s, brothers Ralph and Edmund Messert realized that following in their father’s footsteps in the cemetery monument business wasn’t what they had in mind. They owned a long, narrow piece of land along Aurora Avenue and decided that it would be an ideal location for a hamburger stand. After doing their research, including several trips to California to get a firsthand look at the newest drive-ins there and learning about the local drive-in business from Gil Centioli of Gil’s Hamburgers on Rainier Avenue, they opened Dag’s Beefy Boy at 800 Aurora in 1955.

Taller’s windows faced onto Aurora Avenue, letting motorists observe the charcoal broilers in action. Seattle Municipal Archives, 78405.

Two penguins danced atop the twin domes of the Igloo, at the corer of Aurora Avenue and Denny Way. Seattle Public Library, spl_wl_ res_00228.

Dag’s (a nickname of their father’s) specialized in nineteen-cent hamburgers (six for ninety-seven cents). According to Seattle Times columnist John Reddin, Dag’s claimed to sell four hundred steers’ worth of beef a year plus four tons of french fries a week. Introducing their signature Dagilac and Dagilac II burgers in the 1970s, Dag’s pulled in traffic off the highway with a readerboard displaying witty and occasionally perplexing mottos such as “Feel Wanted—Dag Wants You to Eat at Dag’s” and “Dagilac II—Poetry in Hamburger.” They even earned a place in fast-food history with a new concept: left-handed burger buns.

By 1961, Dag’s had added several more locations: Rainier Avenue at Empire Way and Fourth Avenue S at Lander Street. Both locations sported interesting features like ceramic tiles across the front of each building and glassed-in stainless steel kitchens in full view of customers. Sadly for its many fans, Dag’s closed in 1993.

Dag’s was as well known for its humorous signs as for the nineteen-cent burgers it sold by the truckload. Paul Dorpat.

Les Teagle’s was just one hundred yards up the highway from Dag’s; gastronomically speaking, it was a world away—a high-end dinner house with fine linen tablecloths and silverware, with exposed wood beam ceilings and a view overlooking Lake Union. Teagle’s first restaurant, located at Eastlake Avenue and Thomas Street, east of Lake Union, was operated by his wife, Rita. By 1960, he had established his namesake restaurant at 920 Aurora. Larry and Margaret Anderson of the Seattle Times remembered Teagle’s as a “ritzy spot we went to on our way to formal dances.”

Teagle retired in 1965, and the restaurant was purchased by Dave Cohn, a well-known Seattle restaurateur. The new owners kept Teagle’s name—it was now known as Teagle’s After Five—and continued the tradition of fine dining. After a 1966 visit, Seattle Times food critic Everett Boss portrayed Teagle’s as “a gustatory gratification that will not soon be forgotten, having been enchanted by the astonishing continental cuisine and service…a jewel in the crown of our Queen City—an absolute must for the adventurous palate.”

Danish-born manager Palle Wilms and chef Bob Frandsen created a menu offering seafood selections, including Oysters Villeroy, Lobster Newberg, Prawns Orly, King Crab Legs Orly and Sole After Five (their signature dish, sautéed sole covered with crab meat, béarnaise, asparagus and sliced crab legs); Veal Oscar; Russian Stoganoff (“a tantalizing creation of choice tenderloin beef with fresh mushrooms, sour cream, spices and a touch of wine”); and standards such as prime rib, tenderloin, filet mignon and lobster. The dessert highlight was crepes—strawberry, pineapple or chocolate.

In 1968, Jack McGovern’s Encore replaced Teagle’s, with “prime rib and a gracious dining atmosphere…specialties of the house.” Two years later, the Encore became Dickinson’s Table, “a new experience in fine dining” featuring prime rib (“sold by the inch!”) and a steak and lobster combo for $5.75. Dickinson’s didn’t last long; the following year, Jack McGovern reacquired the property and reopened as Acapulco, a Mexican restaurant where chef Arturo Cota guaranteed authenticity in his cuisine. In 1972, it was the Lulubelle Restaurant; a year later, it became the Ocean House, the name it kept until ceasing business in 1979.

Few businesses developed along the section of Aurora Avenue that clung to the edge of Queen Anne Hill. One exception was the Tiger Inn, which opened for business almost immediately after dedication of the Aurora Bridge in 1932. Owned by Mrs. N.H. Dahl, the inn’s specialties were “superb hot roast beef,” chili and hamburgers. By 1936, the location had been taken over by the Aurora Furniture Company. Today, its location, 2556 Aurora, is the parking lot for Canlis, Seattle’s most esteemed restaurant.

Teagle’s was practically next door to Dag’s but a world away, culinarily speaking, with linen tablecloths and an impressive view of Lake Union. Seattle Municipal Archives, 26749.

Just north of the Aurora Bridge was Dee’s Cafe at 3818 Aurora, a small place that lasted for a dozen years before silently disappearing. Long after Dee’s had disappeared, a takeout chicken place called the Broaster opened in 1962 in the next lot north.

Ida & Gene’s was another restaurant that developed multiple personalities over the years. Located at 3926 Aurora, it was opened in 1954 by Ida Floresca and Genevieve Laigo and advertised the finest steak and chicken in Seattle. By 1962, it had become the Lapu Lapu, with “unusual and distinctive Philippine cuisine, reminiscent of the romantic South Pacific Isles…Delicious Chicken Adobo for a taste thrill. Real Mango ice cream will be an enjoyable finish to your ‘adventure’ in dining Philippine style.” Chef Luiggi’s Restaurant had moved in by 1976; three years later, it was the Bamboo Tree Restaurant, and the following year it became the Siam Restaurant. A hotel, Staybridge Suites, now occupies the site.

At 4012 Aurora was Wright’s Cafe. Owner Carl Belasco had an interesting history: orphaned with two brothers when tragedy struck the family farm in Nebraska, he was sent to Boys Town, the home for at-risk youth made famous by the 1938 movie in which Spencer Tracy played the role of Father Edward Flanagan, its founder. Belasco came to Seattle in 1928 and learned the restaurant business from Mrs. Chauncey Wright, widow of the well-known restaurateur. After she died, he bought one of the Wright restaurants from her estate. He kept the name when he moved to his own place on Aurora in 1940. Wright’s became a popular meeting place for north-end civic organizations such as the Kiwanis. In 1946, Belasco moved Wright’s to a new location a few blocks away at 4220 Aurora, and 4012 became the home of the La Patina Inn and, by 1956, Casa DiNapoli, owned by Dan Catone. Wright’s was gone by 1960.

Mr. and Mrs. Ernest J. Leak operated several restaurants, including one in Puyallup, another along the Mount Rainier Highway and a third called Leak’s Little Canyada Inn on Pacific Highway S in Des Moines. In 1948, they opened Leak’s Chicken Dinner Place at 4132 Aurora. An all-you-can-eat chicken dinner for $2.50 was the featured menu item, along with choice steaks and homemade pies. Leak’s had apparently disappeared by 1958.

A block farther north was Helen’s Roundup at 4252 Aurora. Opened in 1954, it had become the Quality Pancake House by 1963, operating under franchise from the famous Original Pancake House in Portland. A wide variety of pancakes—Alaska Sourdough, Old Yankee Yeasty Buckwheat, French Pancakes with sec suzette topping and German—were on the menu, along with standard breakfast fare such as eggs, ham, bacon and waffles. A few years later, the American Oyster House was at that address. Pancakes were still on the menu; it’s recorded that in 1968, co-owner Mildred Milbrad was fined fifty dollars for slapping a customer after he complained about the restaurant’s specialty pancakes.

With twenty years of experience in the Seattle restaurant business, Thomas Jensen opened King Oscar’sSmörgåsbord in 1940. Unfortunately, Jensen, who had operated the Waldorf Hotel dining room, Jensen’s Queen Anne Café, the Wild Cat Cafe on Westlake and the Hi-Ho Cafe on lower Queen Anne, passed away a few years later, leaving his wife, Amy, to run the restaurant until son Bill Jensen took over operations after his discharge from the army.

Describing a visit to King Oscar’s in 1949, Seattle Times columnist Nat Lund recalled: “The smorgasbord itself is the main feature, and the huge silver candlesticks hidden, so awash are they with Scandinavian delights.” Among the variety of dishes were korvkoko (chicken livers and barley topped with tart lingonberries), liver paste, herring in sour cream, pickled beets, Swedish brown beans, steaks cooked “old country style” (sautéed, not broiled), cold roast beef, smoked salmon, homemade crock cheese, various salads (macaroni; fruit; tomato and cucumber; and cottage cheese) and rice custard pudding. Bavarian Chicken Breast en Casserole and Swedish pancakes filled with chicken and mushrooms were house specialties.

Bill Jensen claimed a smorgasbord wasn’t the real thing unless it had at least sixty different items on the buffet table. He gladly provided novices with advice on how to approach a smorgasbord: “It should be eaten in four courses. First, the fish and appetizers. Then the salads, cold meat and pickles. Third, the hot dishes—Swedish meatballs, beans, ham. And lastly, the cheeses.” Dessert, if the diner felt it to be needed after sampling all the dishes, was Swedish pancakes served with lingonberries and homemade syrup. Customers unfamiliar with smorgasbord, or unwilling to try something new, could order off a complete menu of American dinners, specializing in salmon, oysters, broiled lobster and prawns.

King Oscar’s was located at 4312 Aurora, housed in what once had been an elegant private mansion with two massive chimneys and typical Victorian trim. A twin-gabled Bavarian-style façade was added to give the place an authentic feel, and the Scandinavian mountain chalet theme was continued inside with dark wood, tapestries and vibrant colors throughout the restaurant. Originally open only for dinner, it added lunch service in 1968. The Fjord Room, a cocktail lounge, was upstairs from the restaurant with a view out over Lake Union. A novelty drink for two called “the Voyager” was served in a bowl with miniature Viking ships afloat in it.

In 1977, King Oscar’s became the Cedars of Lebanon, owned by Wajih Alawar and hailed by food critic John Hinterberger as “an oasis of Middle Eastern cuisine in the shifting sands of fast-food emporiums that line Highway 99.” It later became Simonetti’s, an Italian restaurant. Even after the name changes, the King Oscar Alumni Association, made up of those who had enjoyed dining at the old King Oscar’s, held reunions there. The building was extensively damaged by fire in 1984 and eventually demolished.

6 chicken breasts

Flour

Salt

Ground pepper

¼ teaspoon thyme

½ cup butter

1 tablespoon dehydrated chopped onion

¼ cup chicken broth

½ cup white wine

12 slices ham, cooked

½ cup light cream

1 teaspoon parsley flakes

Shake chicken in flour with salt, pepper and thyme. Sauté breasts in butter until brown. Add onion, broth and wine. Simmer, covered, 30 minutes. Stuff ham slices into slits cut at each side of breasts. Stir cream and parsley into broth and pour over chicken in individual casseroles. Bake 10 minutes at 350°. Serves 6.

At 4900 Aurora was the Chuck Wagon Bar-B-Q, its neon sign highlighted by the head of a bull and flashing out what was on the menu: barbecued spareribs, ham, beef and hamburgers. Carhops dressed western style, complete with silver dollar–studded leather belts, provided curb service. Located as it was near the south end of Woodland Park, the Chuck Wagon made a specialty of providing a “quick pickup packaged lunch” (spareribs, French bread, salad, coffee, knife, fork, spoon, paper cups and plates and napkins) to take into the park and enjoy picnic style. The Chuck Wagon survived into the 1990s but has been replaced by an office complex.

Just north of the Chuck Wagon, Aurora begins its tree-lined, three-quarter-mile run through Woodland Park—the long-disputed section once known as the Aurora Speedway—to emerge at Green Lake. Straight ahead at 7701 Aurora stood the crown jewel of Seattle’s roadside architecture, the Twin T-P’s.

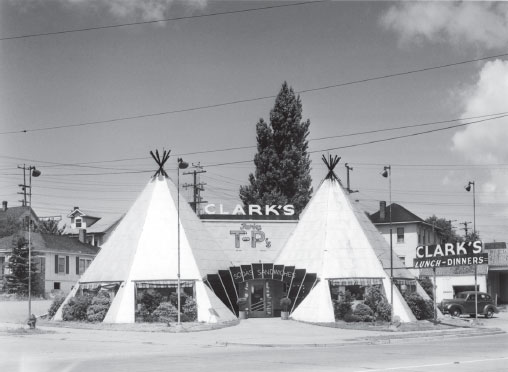

Herman Olson conceived a novel design for a roadside attraction: a restaurant constructed in the shape of two huge adjoining Indian teepees. He registered his design (he called it a “resort building”) with the U.S. patent office, obtained a construction permit in 1936 and got busy. In March 1937, his vision, the Twin T-P’s, opened to great fanfare.

Per its name, the Twin T-P’s consisted of two Indian teepees constructed of crimped metal fashioned over concrete forms with an interconnecting entryway. The teepees stood nearly twenty-five feet tall and were outlined with neon lights. Located where it was, on busy Aurora Avenue just across from beautiful Green Lake, the Twin T-P’s was an amazing sight and immediately became popular both with local and passing motorists.

Each teepee housed a spacious dining room. The main dining room, in the southern teepee, held fourteen booths that seated 56 persons with additional tables accommodating 18 more. A huge open fireplace occupied the center of the room. The second teepee contained seating accommodations for another 40 persons with a counter, booths and fountain service, for a total seating capacity of about 115 customers. The kitchen was located behind the lobby-like entry and took up portions of both teepees. Restrooms were upstairs on the second floor of the lobby.

The café was inspired by Indian designs. Massive murals on the walls, created by artist Alan Nothhof, depicted native lives and legends. Each mural (eight in all) had a name and portrayed a specific subject, such as Chief Seattle, Famous Chief of the Duwamish and Suquamish Tribes, Friend of the White Man; Striped Wolf, Indian Warrior; and Morning Star, Tribal Beauty. The ceilings were painted with designs based on Northwest Indian motifs.

In 1939, the menu offered two price options for dinners: $0.85 and $1.10. For the latter price you would get a choice of cocktail (fruit, shrimp or crab) or soup, a salad with French dressing, choice of New York–cut sirloin steak or half a pan-fried chicken, hot biscuits with jelly and a dessert: pie, cake or ice cream sundae. À la carte items included chicken potpie and chicken fricassee. Sandwiches, such as baked ham, sliced chicken and tuna fish, cost between $0.20 and $0.35. Several distinctive sandwiches were also on the menu, including fried Willapoint Oysters and a Monte Cristo, as well as the ever-popular T-P Burger.

The Twin T-P’s pride was its fountain service. Original fountain specialties—most of them named after the murals—included the Chief Seattle Sundae (two scoops of ice cream on split banana, chocolate, marshmallow topping, whipped cream and nuts; thirty cents). The Morning Star Sundae (vanilla ice cream, orange sherbet, pineapple, fresh banana ring, whipped cream and cherry) was also thirty cents. The Striped Wolf Sundae (just twenty-five cents) had vanilla ice cream (double-dipped), Dutch chocolate topping and shaved chocolate, whipped cream and chocolate decorettes.

In August 1939, veteran Northwest restaurant man Frank Holzheimer took over operations, with Homer Richards replacing Arthur Apgar as chef. Walter Clark purchased the Twin T-P’s in 1941, adding it to his growing restaurant empire, and the name changed to Clark’s Twin T-P’s. With a new manager and chef (Meigs Close and James Cheek, respectively), Clark modernized the restaurant by “blending an historic background with today’s latest ideas in food service…smart surroundings, delicious dishes to whet every appetite, modest prices to meet the most careful budget!” Among other changes, the booths were redesigned to provide a better view of Green Lake, and the T-P’s began staying open “from morning ’til way past midnight, at counter, booth, or table.”

The story goes that around 1942, Clark offered a job to an old friend who was looking for work—a fellow named Harland Sanders. It seemed that Sanders was less interested in flipping hamburgers than working on his chicken recipes, however, and he soon parted company with the Twin T-P’s, returning to his native Kentucky to find fast-food fame as Colonel Sanders with his Kentucky Fried Chicken franchises.

The Twin T-P’s were remodeled again in 1949, and prices increased: luncheons were now $0.85, dinners $1.50. By 1958, Walter M. Power had bought the place and renamed it Powers’ Pancake Palace. The teepees were painted orange; a huge waffle was installed over the entryway, and a giant stack of pancakes adorned the side of the south teepee. In 1968, the old name was restored, but by the late ’70s, the spelling had changed: it was now the Twin Teepees, and it remained for the next thirty years.

The restaurant suffered a fire in July 1997 and a more serious blaze in June 2000. Claiming the expense of repairs and necessary upgrades such as removing asbestos and lead-based paint were too expensive, the current owner applied for a demolition permit. In July 2001, the restaurant was bulldozed—an event that still haunts the memories of Seattle’s historic preservationists.

Seventy-Second Street marked the beginning of the busy Aurora shopping district. As real estate became valuable, residences lining Aurora sprouted storefronts in their front yards within a decade; practically the entire six-block stretch to Eightieth Street was filled with shops, restaurants and service stations.

The Aurora Grill was a storefront café at 7301 Aurora run by Mr. and Mrs. Rau from about 1948 to 1957. Next door at 7305 was Mac’s Barbecue. Eunice Marshall ran it for several years before illness forced her to sell it in 1932. New owner George McLaughlin occasionally took out an ad in the Seattle Times, urging readers to “take the family to Mac’s Barbecue for a real treat.” By 1948, it was the Meet Me Here Tavern, apparently no longer in the restaurant business. Pep’s Hamburgers was another early eatery at 7317 Aurora and was still in business in 1964, though the place was practically demolished by a runaway truck that year.

The Twin T-P’s as it looked in 1942, when it was part of Walter Clark’s restaurant empire. Museum of History and Industry, 1983.10.17115.1.

Hildegard’s Chicken Dinner Inn was an elegant dinner house that shared the building at 7401 Aurora with a bicycle shop. With fine linen tablecloths and napkins, flowers and candlesticks on its tables, windows masked by wood-slat blinds and heavy drapery and mural-painted walls, Hildegard’s projected an aura of genteel dining. Owned by Hildegard Allen with Stan Asmundson as chef, Hildegard’s opened to diners in 1946 and soon became well known for charcoal-broiled steaks and butter-fried chicken. Duncan Hines recommended Hildegard’s. By 1957, Diamond Jim’s occupied the premises, and Hildegard had moved on to manage the Tropics Motel restaurant and lounge. Still standing, the building is a motorcycle shop today. The next two blocks saw a number of restaurants come and go in a twenty-year period, among them Matt Fogarty’s Restaurant at 7404 Aurora; a place called A Real Cafe at 7501, which went through five owners in eight years before becoming the A.C. Tavern in 1937; the Woodland Restaurant at 7606, open as early as 1928; the Kodiak Cafe at 7608; the Royal Cafe two doors away at 7616; and Florence & Marie’s Coffee Shop, located at 7617 Aurora Avenue and also known as the Huddle Cafe.

At 7701 Aurora Avenue stood the Dixie Flyer Diner. Soon after arriving in Seattle in 1945, Virginia natives Clifton and Edna Prichett realized that their new home city lacked a modern dining car—the type of classic stainless-steel-and-porcelain beauty common on the East Coast but rare out West. They purchased a 1946 “Challenger” model from the Kullman Dining Car Company of New Jersey and had it shipped across country by railroad for $1,000. While they waited nine months for the building to arrive, the Prichetts built a kitchen, pantry and restroom behind where the diner would be located.

The Dixie Flyer opened in January 1947. The gleaming new dining car immediately became popular with Seattleites and, as something of a novelty in the Pacific Northwest, attracted scores of curious tourists and long-haul truckers, as well as locals frequenting the busy Aurora shopping district. The diner was open from 8:00 a.m. until 2:00 a.m. daily except Tuesday, when the staff—the Prichetts; Mrs. Prichett’s sister, Grace Woods; Edith Snipes; Martha Freckleton; and ex-navy chief commissary steward Johnny Clautier—took a well-deserved morning off. The four large booths and fifteen stools seated thirty-one people, and there was often a line waiting to get in. Off-street parking for twelve autos was offered, with a rear entrance for those wanting to avoid Seattle’s legendary rainfall.

The Dixie Flyer’s staff took pride in their southern hospitality and home cooking, always served with a smile. The menu offered daily fifty-cent lunch specials as well as T-bone steak dinners, hamburgers and hamburger steak. The diner became famous for its Denver sandwiches and for serving breakfast—buttermilk hotcakes and ham and eggs—at all hours. The Prichetts put in plenty of elbow grease to keep their diner sanitary and shining; baked goods and pastries were displayed in built-in glass cases, and food was kept in tightly covered stainless steel pots.

Despite several years of success, by 1952, the Prichetts were apparently encountering personal difficulties. In June that year, Clifton and Edna Prichett were divorced. A month later, an advertisement appeared in the Seattle Times offering a stainless steel diner for sale. It’s not certain that it was the Dixie Flyer, but no other diner in Seattle matched the description. Apparently no sale took place, because Edna Prichett continued to be listed as the diner’s owner in Seattle business directories for the next few years.

In June 1955, the diner was purchased by Andrew Nagy, owner of Andy’s Diner at 2711 Fourth in South Seattle. By 1956, the Dixie Flyer had been renamed Andy’s Too Diner. For the first several years after Nagy purchased it, the diner was operated by his nephew, Andrew Yurkanin, who functioned as cook, manager, greeter and occasional waiter.

In 1958, the diner was moved from its North Seattle site to 6151 Fourth Avenue S, about a mile south of Andy’s Diner. Aurora Avenue was becoming more residential, there was too much traffic on Aurora for motorists to stop easily and there was more business in the rapidly developing south end. The diner’s story at its new location, and that of the original Andy’s Diner, will be told later in this chapter.

Next door to the Dixie Flyer but preceding it by twenty years was the White Kitchen, at 7909 Aurora, Maybelle Blecker, owner. At 7714 was a delicatessen owned by Lauchlin McLean in 1939. By 1941, new owner Thomas Barber had renamed it Barber’s Delicatessen. In 1948, it was Goodall’s Fountain Lunch, a fountain lunch, ice creamery and delicatessen; between 1951 and 1956, it became the Peacock Inn. Today it is Pho Thân Brothers, a Vietnamese restaurant.

In 1941, an early health-food place, the Nutburger, stood at 8018 Aurora (“nutburger” being a burger-shaped patty of ground nuts and flavorings). By 1948, Hawley’s Drive-In stood there; in 1956, Cafe Avel replaced Hawley’s, and Chapala Mexican Dinners took over in 1974. Bill & Paul’s Hamburgers opened at 8412 Aurora in 1930, when this segment of the highway was still called Woodland Park Avenue. Almost immediately, it went through the usual changes in ownership, being known as the City Line Cafe for a time—until 1954, Eighty-Fifth Street marked Seattle’s north city limit. The café was gone by 1941.

Zip’s 19¢ Hamburgers, at 8502 Aurora Avenue, opened in 1955. In 1963, it added Zippydogs to the menu for nineteen cents—same as the burgers; cheeseburgers were twenty-four cents—plus two new locations: First Avenue and Denny Way and Forty-Fifth Street at Roosevelt. They all seem to have disappeared by about 1967. A Jack in the Box now occupies the Aurora location. Although they aimed for the same market, these Zip’s don’t seem to have been connected to the chain of Zip’s Drive-ins started by Robert “Zip” Zuber in Kennewick in 1953; the signage is different.

The quarter-mile stretch of Aurora between Eighty-Fifth and Ninetieth Streets saw a number of lunch places come and go in the ’30s, including Walt’s Hamburgers at 8511 Aurora and the National Cafe across the street at 8520. In the 1950s, Little Audree’s Cafe, later known as the Bob-o-Link, was next door to the National. Mr. and Mrs. A.J. Sauers operated a lunchroom and ice cream parlor at 8816 Aurora. First called Bill’s Cafe, it was the Rafters Cafe in 1949 and Tiny Tim’s a few years later. The Sauerses turned their attention to building a motel behind the café, and by 1956, the lunchroom had disappeared, with the motel taking over the whole building.

This Zip’s 19¢ Hamburers, part of a local chain of three, was on Aurora Avenue at Eighty-Fifth Street. Seattle Public Library, spl_wl_res_00229.

The stone-front building still standing at 8904 Aurora was the White Stone Tavern & Cafe for many years, offering food and drink served in its fireplace lounge. In 1979, its name changed to the Brooklyn Bridge, and it was called Mel’s in 1981. Today, the Jade Restaurant and Lounge occupies the site. At 8954 Aurora was Sally’s Sandwich Shop, run by Mrs. Sigrid “Sally” Foss in the early 1930s. Offered for sale in 1933, it became the Shamrock Tavern, a typical burgers-and-beer place operated in partnership by Ercole Tiberi and Ralph Pelegrini.

In 1935, Pelegrini suddenly accepted a job offer in Wenatchee and left his wife to look after his interests. She and Tiberi apparently didn’t see eye to eye about how the place should be run, so they divided everything 50/50—each took exactly half of the beer, four of the eight bar stools, ten of the twenty toothpicks, one of the two cans of popcorn and so on, though a problem arose when they counted sixty-three napkins—not an even number; so they each took thirty-one and evenly divided the leftover. They even cut the bar counter in half, though they couldn’t divide the booths—they were nailed to the floor, and the landlord quashed the idea of ripping them out. Tiberi continued running the tavern for a few more years before selling out to John Ghetti in 1936. It’s gone now.

Jack Case ran a café at 9012 Aurora as early as 1937. That same year, a hamburger cost ten cents at the Flying Boots Cafe, across the street and slightly north at 9053 Aurora. They charged thirty-five cents for their special home-cooked dinner. A place called Had’s was farther up Aurora at 9418 in the ’50s. Sealy’s Fish and Chips was at the intersection of Aurora and Ninety-Fifth Street. In 1948, you could grab a quick bite in Doran’s Cafe at 9724 Aurora. By 1962, it had become Henning’s Charcoal Broiler, open for breakfast, lunch and dinner with steaks, chicken and seafood on the menu. By 1967, Venetti’s La Strada Restaurant occupied the address and survived into the 1980s.

The Snow White Cafe, at 10123 Aurora Avenue, opened sometime around 1942 and went through several changes of ownership in the next few years. The interior layout was typical for the times—lunch counter on one side of a long, narrow room, booths against the other wall. In 1954, the café was owned by Thomas Argeris and managed by Gladys Brown. That year, a school bus, swerving to avoid a small child playing in the street, struck the front of the café and caused major damage.

Several cafés clustered near the busy intersection of Aurora Avenue and 105th Street in the 1950s, including the North Park Cafe at 10309 Aurora and Eve’s Cafe at 10332. The Bon Ton Cafe was open twenty-four hours a day, serving up fried chicken, steaks and homemade chili. An early arrival, the North Star Cafe, was at 10413 Aurora in the 1930s.

A Triple XXX Drive-in variously known as Lindquist’s, Pederson’s and Pappy’s stood at 12255 Aurora for several years. In 1954, the LeMar Drive-In occupied the spot, and in 1960, it became Smitty’s Pancake House. Today it’s the location of a newer restaurant, the 125th Street Grill.

The Village Inn was part of the National Auto Village auto court complex at 125th Street and Aurora Avenue. The inn was a squared-log façade to the court’s stucco tile–roofed main building and served the basics—hamburgers and beverages (probably a euphemism for beer)—to the auto court’s guests as well as highway travelers.

Curly’s Drive-In was a bit unusual in that it offered inside dining, complete with a cozy fireplace hearth, as well as drive-up service. Chicken, hamburgers, french fries and fish and chips were on the menu. Located at 12752 Aurora, Curly’s had become Art Lee’s Chinese Restaurant by 1966.

Today, the site is part of an auto dealer’s parking lot. Hugh Sloan operated Dee Dee’s Cafe at 12804 Aurora, changing the name to Sloan’s Fine Foods in 1956. After Sloan passed away the following year, it became Snyder’s Restaurant and was gone by 1964.

At 13104 Aurora was the Port Hole Drive In, a restaurant built in the shape of a ship. Its first incarnation was fairly simple—a modest boat-shaped building containing the kitchen and order windows, with a covered awning on either side to protect drive-up customers from the elements. (They made the ship look like it had wings.) It opened in 1952 and was purchased later that year by Frank Wnukowski, who remodeled and expanded it the following year. A total rebuild took place in 1959—a massive two-story structure with “jet-age, swept-wing canopies extending 150 feet to the highway.” Wnukowski named it Frank’s Port Hole to distinguish it from its predecessors. Both inside and drive-up service were provided (11:00 a.m.–3:00 a.m. every day) by waitresses in nautical garb. Located as it was near the popular Aurora Speedway racetrack, it was a busy place.

Wnukowski opened yet another restaurant at this same spot in 1965. The Neptune was a complete departure from the earlier ship-shaped design, with a three-peaked roofline sporting the colorful figurehead of King Neptune and three mermaids. The 3,300-square-foot restaurant of masonry and wood-framed glass with stone wainscoting along the front seated 150 customers. Interior decoration was done in tones of beige, white and gold. Predictably, the Neptune featured seafood on its menu. The old Port Hole building remained standing nearby for a couple years, but eventually both it and the Neptune gave way to redevelopment. Today, it’s a parking lot.

The Village Inn was attached to the National Auto Village, an early auto court on Aurora Avenue. Washington State Archives Puget Sound Regional Branch.

An early auto court dating back to 1932, the Red & White Cabins, stood at 13575 Aurora. By 1948, it had been renamed the Paradise Motel, and a small café was built along Aurora at the motel’s entrance. The Paradise Cafe served up standard fare: steaks, fried chicken, sandwiches, chops, chili, ravioli, malts, shakes and ice cream. A large plate-glass window gave diners a view of traffic out on the highway; the door, set into a corner of the building, was surrounded by glass blocks, something of a fad of the times. There’s an auto dealership at that address today. At 14025 Aurora, Swanney’s offered fish and chips in the 1930s. A few decades later, the Tik-Tok Drive In opened at 14040 Aurora. Later known as El Chico, part of the building still stands.

Seattle proper ends at 145th Street, the city limit since 1954. This was a very lightly developed region when the Seattle-Everett Highway opened in 1927. The highway ran through miles of cut-off timberland and small farms (often derisively referred to in the city papers as “chicken ranches”). In short order, this stretch of highway became the domain of the roadhouses. By the 1940s, most of those had disappeared, and legitimate roadside businesses started popping up all the way to Everett.

North of 145th Street are the communities of Shoreline, Richmond Heights, Edmonds and Lynnwood. We’re getting beyond our main focus now, but a couple of noteworthy places should be named.

Alexander “Jerry” Girard opened the Golden Tub in 1930 and operated it until retiring in 1944. It was located at 14507 Aurora. Farther up the highway was the Hilltop Cafe at 14845 Aurora. In 1935, it advertised that it specialized in fried chicken, a $0.25 lunch and delicious sandwiches. At 15744 Aurora was the Garden Spot café and tavern. In 1951, it became Snuffy’s Cousins and was owned by Mr. and Mrs. Tom Horn. Briefly renamed Bob’s Grill in the mid-1950s, the original name was restored a few years later. Food reviewer Steve Johnson visited Snuffy’s in 1976 and had good things to say about the extensive menu: breakfast served anytime with more than a dozen omelets available; ham, egg and hash browns made with real potatoes for $2.45; and fast and friendly service. Shay’s Restaurant took over in the 1980s and is still in business.

Bessie Haines ran the log cabin–style Bessie B Lunch for forty-five years before retiring in 1956. Shoreline Historical Museum, 65.

In 1921, Bessie Haines opened a lunch counter in husband Roy’s garage to serve passengers at the nearby interurban station. By 1928, she had moved to her own building—Bessie B Waffle Shop and Lunch Room—on Aurora Avenue at N 185th Street. Inside were a dark wood lunch counter and whitepainted tables and chairs, with a fireplace and mantel along the north wall. A sign above the door advertised trout dinners. The log cabin–style building replaced the earlier lunch room in the early 1930s, a few feet farther south on Aurora. Bessie’s was a familiar landmark for highway travelers as well as locals who met for “coffee hour.” Bessie sold the café in 1956 to Mr. and Mrs. William Plouff, who had operated Anabel’s Cafe in the Greenwood neighborhood. The café lasted for a few more years but is now gone.

HIGHWAY 99 SVIA FOURTH AVENUE S AND E MARGINAL WAY

Highway 99 heads out of Seattle on Fourth Street S on its run south before turning onto E Marginal Way and eventually climbing the hill above the Duwamish River on its way toward Tacoma. For some reason, this section of the highway didn’t develop as many roadside restaurants—in 1951, fewer than a third—as grew up along an equivalent distance to the city’s north.But among them were some now-lost gems.

The 4th Ave. Drive-In debuted in 1940 at 1245 Fourth Avenue S. Something must not have gone according to original plans; within a year, it had been completely remodeled and was under new management: R.J. Rusden, who also owned a Triple XXX root beer barrel on Olive Way and another in Everett. Though called a drive-in, it was actually more of a full-service restaurant serving breakfast “the way you like it…fresh-from-the-farm eggs and sugar-cured ham and bacon,” a variety of tempting dishes for lunch and melt-in-your-mouth steaks and fresh salads for dinner. Ready anytime were hamburgers, barbecued beef and pork sandwiches and apple pie. Inside were booths and a counter, with outside curb service at all times. Chef Emily Lacey took pride in serving complete Sunday dinners—$1.25 for roast turkey, cocktail, soup, vegetables, dessert and beverage.

By 1962, the drive-in had become Budnick’s Chez Paree Restaurant, owned by Richard Budnick and offering “‘Steak Bordelaise’ that’s ‘Terrifique’” in contemporary and French décor. It was still Budnick’s in 1970 but sliding more into a go-go bar sort of place. The change wasn’t successful; it closed a year later.

The 4th Ave. Drive-In was bright, shiny and new when this photo was taken in 1940. Seattle Municipal Archives, 18872.

Don Cruikshank, aka Mr. C, moved in in 1973. Mr. C’s menu listed fifty different kinds of hamburgers ranging in price from sixty cents to fifty dollars. Each burger creation was named after a state:

Maine—burger steak and grilled prawns

Minnesota—a combination of a third of a pound of beef and a slice of Canadian bacon

New York—hamburger, raw onions and a Kosher pickle

Montana—a burger with three different melted cheeses: cheddar, Monterey jack and American

Massachusetts—it came with a pot of baked beans

Florida—topped with an egg, sunny-side up

Least expensive was the Rhode Island (a child’s-size burger—no offense, Rhode Islanders). At the top end was the fifty-dollar Alaska, a ten-foot-long hamburger served on a hardwood plank with fries.

Mr. C said he got the idea from all-burger places in California.

Let’s face it, everybody loves a good hamburger. I just decided to add a few dimensions. Like where else in town can you get a hamburger served with stemware and linen napkins?

But the strangest thing was the time a guy called up and ordered one Alaska burger to go. First I made sure he was on the level. And he was. Then I told him that taking out an Alaska burger to go was not an easy thing. He said he could handle it. Sure enough, he showed up with a Volkswagen van and stuck it in the back. I watched him drive off. He had three feet of hamburger sticking out the back.

Mc. C’s lasted for a few years before turning into the Meat Market, a cabaret/comedy nightclub. It was gone by 1981.

The spirit of Andy’s Diner still resonates with Seattleites. A longtime fixture along Fourth Avenue S, Andy’s was famous for charbroiled steaks served in actual railroad cars and its collection of authentic railroad items and pictures. The diner was the brainchild of Andrew Nagy Jr. After four years in Reno working at a hotel restaurant, Nagy relocated to Seattle and in July 1949 opened “a novel dining spot…a regulation steel dining car with the wheels removed and fitted it up as an attractive café” at 2711 Fourth Avenue S, about a mile and a half south of the central business district. In 1956, Andy’s Diner moved another mile farther south to 2963 Fourth Avenue S, and it’s this incarnation that Seattleites fondly remember.

Nagy’s nephew Andrew Yurkanin had joined him in the restaurant business in 1955 as manager and jack-of-all-trades at the soon-to-be-renamed Dixie Flyer Diner on Aurora Avenue. When the former Dixie Flyer was moved to Fourth Avenue S in 1958, Andy Yurkanin followed suit and continued to manage the rechristened Andy’s Too Diner. By 1959, he had become a full partner with Nagy and moved uptown, as it were, to Andy’s Diner. (The Andys were familiarly referred to as “Big Andy” [Nagy] and “Little Andy” [Yurkanin].)

By 1959, the diner’s business was booming. More railcars—a bar car, a club car and an executive car—had been added, and an entrance building had been constructed. Andy Yurkanin recalls the diner’s golden years: “We served about 1,200 people at lunch on a good day—we had capacity for 380 people, and we filled the place three times over. We also served between 200 and 400 dinners.” The fare was originally typical diner food, with a growing focus on steak and prime rib dinners. Saturday, the busiest night, kept longtime employees Alberta Lemonde and Betty Ayers active. Thornton “TA” Wilson, Boeing Company chairman, was a regular customer, stopping in three times a week.

The Andys began expanding their business as early as 1961, when they decided to create a chain of restaurants based on Li’l Abner, the cartoon character created by Al Capp. Only a single Li’l Abner’s saw the light of day, however—apparently hillbillies couldn’t compare with railroads when it came to restaurant themes—and by 1964, the concept was defunct. Undeterred, Nagy and Yurkanin opened a string of successful restaurants in the 1970s: Andy’s Tukwila Station in 1976, the Eugene Station (now called the Oregon Electric Station) in Eugene in 1977 and Andy’s Auburn Station on C Street in Auburn in 1980, among others.

After Andy Nagy passed away in October 1980, Andy Yurkanin carried on until his retirement in 1996 after nearly forty years in the restaurant business. His son ran the restaurant for a few years until it was purchased by two local businessmen. The end came in 2008 when Andy’s closed its doors. In a sense, Andy’s Diner lives on; its collection of railroad cars is still in place and functioning as a restaurant called the Orient Express. But much to the regret of longtime Seattleites, the old-time diner experience is gone.

A bit south of Andy’s was another railroad-car-turned-diner operation, Knight’s Diner, at 5717 Fourth Avenue S. There’s an interesting backstory about Knight’s. Brothers Jack and Frank Knight got into the diner business in Spokane in 1932 when they purchased an old railroad coach car, refurbished it and opened their eponymous Knight’s Diner near the railroad yards northeast of the city. Within a few years, they had become so successful that Frank Knight moved to Seattle to repeat the story. Originally located at 6159 Fourth S, by 1949, the diner had relocated to 5717, across from Kettell’s Drive-In.

Andy Nagy stands on the observation deck of one of the railroad cars that formed Andy’s Diner in 1954. Seattle Municipal Archives, 78429.

In the meantime, the Spokane Knight’s went through a few changes. Jack Knight entered the service in 1943, and the diner’s new owner renamed it the Valley Diner, soon to be renamed Wright’s Diner. In 1950, Jack repurchased Wright’s, gave it back its old name and moved it to Division Street, closer to downtown Spokane. The diner moved again in 1992 to Market Street in northeast Spokane, and there it remains today, still popular and often voted “best breakfast in Spokane.” The next year—1993—the Knight’s Diner in Seattle closed; the railroad car was trucked to Spokane and reopened downtown in 1995 as Frank’s Diner, in honor of Frank Knight. Final score: Spokane: 2 old-time diners; Seattle, 0.

The menu for Knight’s Diner was cut to the same shape as the old railroad car that contained it. Author’s collection.

Kettell’s Corner was a longtime Seattle favorite on Fourth Avenue S at Fifty-Eighth Street, a site occupied in the 1920s by Wray’s Service Station No. 2. Kettell’s Drive-In opened there in the ’30s, and by 1954, a fullsized restaurant had appeared. The food bordered on the greasy-spoon type of cooking—no low-calorie, weight-watchers fare on the menu—but Kettell’s, with its huge sign (including a blinking neon owl), was always popular with the locals and nearly always full. The restaurant made a specialty of preparing takeaway orders—both lunch and dinner—for workers from nearby industrial areas. Nonsmokers remember needing to hold their breath while wading through a cloud of fumes to get to the nominal smoke-free area. It was a shock to the regulars when Kettell’s suddenly closed in 2003. Today, the building contains a gentlemen’s club called Kittens.

The year 1958 saw Andy’s Too Diner, formerly the Dixie Flyer, being moved from Aurora Avenue to 6151 Fourth Avenue S. Just as the Dixie Flyer Diner had been on the main highway north out of Seattle, this new location was along the principal route out of the city southbound. The relocated diner received a few additions: a rear dining room behind and approximately the same dimension as the original diner; a thirteen- by nineteen-foot, two-story addition built in 1960; and eventually a twenty- by fifty-foot dining room added to the rear of the original dining room. Behind the diner was a small building used for storage.

The name of the diner after its relocation is a bit of a puzzle. Longtime manager Andy Yurkanin remembers it as Andy’s Too. Property assessment photos from 1958 and 1960 clearly show a large sign reading “Andy’s Too Diner” in front of the diner. But the Seattle business directories for the same period list the Fleet Diner at this address, and a contemporary photo backs this up. It was apparently also referred to as Andy’s Two and Andy’s Diner No. 2.

This building was a gas station before it became Kettell’s Drive-In in 1948. Kettell’s Corner later occupied the same site. Washington State Archives Puget Sound Regional Branch.

After the Dixie Flyer Diner was transported from Aurora Avenue to Fourth Avenue South, it was renamed the Fleet Diner. Andy Yurkanin.

Whatever its name, the diner seems to have remained in this location until 1964. By July of that year, it had moved again to 4125 Maynard Avenue S, about a mile away. It isn’t certain that the diner ever reopened for business at the Maynard Avenue site. Property records list M.P. Yousoofian as the new owner, but there is no record of any business at that address for the period 1964–69. Sometime prior to 1968, the diner had met its fate: Seattle city property assessment data for 1969 notes that it had been torn down and was off the tax rolls. A McDonald’s now occupies the site on Fourth Avenue S; the Maynard Avenue location is a vacant lot.

Margo’s Restaurant at 6519 Fourth Avenue S started life as the Hungry Junction, so named because it sat at the corner where Highway 99 turned onto E Marginal Way on its way south. Originally a log cabin–style café with a portico facing the street, by 1962, Margo’s had expanded into an austere cinderblock building. Street-side was a totem pole, a stylized thunderbird bearing Margo’s sign. Margo’s was open for breakfast, lunch and dinner; specialties included thin hotcakes, thick steaks and kosher corned beef. Cocktails were available in the Pow-wow Room. Like Kettell’s Corner a few blocks north, much of Margo’s clientele were south end workers, and takeout orders were a big part of the business. Margo’s closed in the early 1960s, but part of the building is still in use as a Vietnamese restaurant.

Originally a gas station, by 1937, the Hungry Junction was selling homemade chicken pies—“Tak’em away in crocks”—and Danish ice cream, 7 Up and Coca-Cola. PSRA.

The Camel Inn went through a number of name changes over the years. This is how it looked in 1964. Washington State Archives Puget Sound Regional Branch.

The famous Budweiser horses parade in front of Verna’s Inn on this old postcard. Author’s collection.

The Camel Inn was another south end restaurant that went through a series of name changes. Opened around 1930 as the Chat & Chew Cafe, it became Leo’s Cafe a few years later, then Pat’s Place before finally settling on its final name. For a number of years, the Camel Inn was a reputable eatery operated by Dick Phillips, but by the late ’60s, it was falling on hard times. The inn—by then, the tavern business overshadowed the café—began incurring liquor permit violations on a yearly basis. An arson fire in 1974 severely damaged the inn, but it rebuilt and struggled on for a few more years. The building, deserted, still stands at 7047 E Marginal Way.

A few cafés lined the highway as it edged the west side of Boeing Field, such as Burnace McNabb’s Kitchenette Lunch, a block south of the Camel Inn; Brodine’s Lunch and Wally’s Lunch, both in the 9100 block of E Marginal; the Little Red School House Cafe, located where the Museum of Flight now sits; and Feek’s Cafe, at 10222 E Marginal nearby to the still-operating Annex Tavern. Verna’s Inn Tavern occupied a brick building of interesting design at 10440 E Marginal Way. Opened sometime around 1950, Verna’s specialized in Italian and American dinners and was open daily from 11:00 a.m. to 11:00 p.m. By the ’70s, a topless joint, the Bear Cave, had taken over the building; it is gone today.

HIGHWAY 10 E

Seattleites who remember the Sunset Highway (aka Highway 10) generally recall it passing through the Mount Baker tunnels and crossing the Lake Washington Floating Bridge on its way east. Few realize that the highway’s early alignment took it south from Seattle around the south end of the lake via Renton before angling northeast toward Issaquah. This route split off from Fourth Avenue S onto Dearborn, then south via Rainier Avenue to Empire Way (today’s Martin Luther King Jr. Way) and on to Renton. There were a few restaurants along the mile and a half of Rainier between Dearborn and Empire when Rainier carried Highway 10 traffic before the route was realigned across the floating bridge in 1940.

The Hitching Post was just south of Dearborn at 1135 Rainier Avenue. Ostensibly a tavern, it also served chicken and steak dinners. It was in business by 1934. The name changed to the Chalet in 1967, became the Brothers Tavern in 1971 and switched back to the Chalet again by 1975. In its later years, the Chalet was what today is called a dive bar: loud music, lots of beer, probably not much by way of food.

Ruby Bailey had a lunch stand at 1348 Rainier in 1932; it later was run by Alice Bridges. At 1503 Rainier was Alice’s Grocery and Coffee Shop, which also sold lunches. The Rainier Cafe, a working man’s place, was at 1508 Rainier in the ’30s. Just down the street, Domonick Yellum opened a tavern in 1933. Five years later, it evolved into the New Italian Cafe and Tavern, run by James Conguista. The New Italian offered typical fare—spaghetti, ravioli, pizza—and was in business until about 1967. All of these places are now buried under the Interstate 90 approach to the Mount Baker tunnels.

Half a mile south were the Bantu Cafe, at 2007 Rainier, and the Siberrian Cafe practically next door. The significance of the names isn’t known, though there was also a Siberrian in West Seattle at about the same time. O.E. Kuehnoel’s Triple XXX root beer barrel stood at 2822 Rainier, right where Highway 10 turned off onto Empire Way. Kuehnoel’s stand was part of the first wave of Triple XXX barrels in Seattle and survived into the 1950s, when it was replaced by a grandiose $100,000 building with covered drive-in stalls for forty-three cars plus regular restaurant facilities inside.

The parking lot at the Bambi Drive-In was torn up for sewer replacement the day this photo was taken in 1949. Seattle Municipal Archives, 10242.

The new Kuehnoel’s Restaurant and Drive-In kept burgers and Triple XXX root beer on the menu but aimed to attract a more upscale crowd with steaks and the house specialty, roast sirloin of beef; in fact, the restaurant’s name was briefly changed to Kuehnoel’s House of Rare Beef. An interesting touch was the Gallery of Contemporary Art, a portion of the restaurant dedicated to displaying work from Northwest artists. In 1967, Kuehnoel sold out to the Standard Oil Company of California (for reasons unknown), and the restaurant’s name became the Spindrift. A few years later, Gil A. Centioli of Gil’s Hamburgers bought the place and added his name to the marquee. The restaurant’s last owners were Bruce and Phyllis Beisold; it disappeared around 1979, and today the site is a parking lot.

Just south of Kuehnel’s, Highway 10 split off from Rainier onto Empire Way. In earlier times, this was a fairly lightly developed section of Seattle, and only a few roadside restaurants developed before the official highway alignment switched over to the floating bridge route in 1941.

At the corner of Empire Way and Hudson Street was the Bambi Drive-In, open for breakfast, lunch and dinner with a soda fountain and curb service. Nearby, the M&R Fountain Lunch was at 3927 Empire Way.

Coyne’s, one of Seattle’s earliest A&W Root Beer outlets, was at 5700 Empire Way, though it didn’t appear until the 1950s—long after the highway was rerouted. In the days when a mug of root beer only cost a nickel, A&W sold pizza and chili dogs in addition to its trademark Papa, Mama and Baby Burgers. Coyne’s also had an A&W on Twenty-Fifth Avenue NE. Across the street at 5705 was the Empire Way Cafe, owned by Bob and Nel Paulsen.