CHAPTER SIX

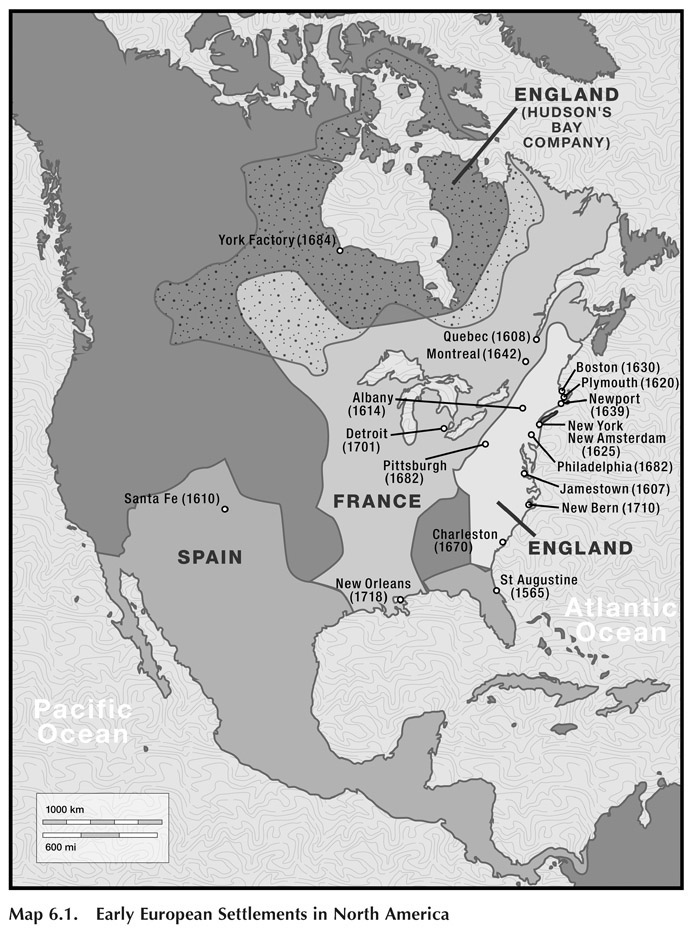

As late as 1600 North America from Georgia north to New England, the Saint Lawrence River, and the Great Lakes was a vast, uncharted area. It had been visited by a handful of Spanish, French, and English explorers, and by Basque and Portuguese fishermen who often went ashore on Newfoundland, the banks of the Saint Lawrence estuary, and the coasts of New England. Based on the scattered information from those sources, it appeared that Atlantic America had no empires to conquer and no valuable mines. Discounting its Native American population, Atlantic America’s only obvious assets were furs and land.

To profit from this part of the New World, one had to either find a way to trade with the Native American people or learn to produce a salable export crop. Using the joint stock company as a way to raise capital, groups of speculators and developers proposed to establish “plantations” in America. Sir Walter Raleigh, using private funds, formed a colonizing company in 1585 and recruited people to settle permanently in Virginia. Overly optimistic about the possibility of finding valuable mines or profitable trade, his colonists included too few farmers and too many gentlemen. That first colony was a failure. Some of the original settlers returned home, but the rest had disappeared without a trace when a supply ship finally arrived. Jamestown, as we will see, had similar supply problems and struggled until the introduction of tobacco farming.

The settlement colony, called a “plantation” by the English, was used to settle people in English North America. The model was first tried in sixteenth-century Ireland and, unsuccessfully, in the Caribbean and Madagascar. These colonial plantations were promoted by investors in a joint stock company with a charter from the Crown. The promoters then recruited settlers with the goal of creating a profitable export-oriented plantation and trading post. This assumed the possibility of trade with the local population and the availability of a marketable crop suited to the plantation’s soil and climate.

The important variant from this model was the Puritans’ Massachusetts Bay Colony. In their case, the promoters and investors were the colonists themselves. They controlled the majority of the stock in the joint stock company and took the actual royal charter with them to the new colony. Their goal was not a profitable export-oriented colony but the settlement of a large number of people at a new location where they would permanently occupy the land and create a self-sufficient European-style settlement. Religious refugees from English persecution, they used the company charter as the basis for self-government, keeping the document itself physically out of reach of English political or religious intervention.

With no large, organized governments in North America waiting to be conquered and no valuable mines, the other options for extracting profit from Atlantic America were to exploit the fur trade or develop a profitable general trade with the Native Americans. This is why the first English, French, and Dutch settlements in North America were planned to be trade centers. Since the indigenous culture did not produce much that would interest European consumers, the most valuable North American export commodity was fur.1

Fortunately for Europeans interested in North America, the first part of the seventeenth century was relatively peaceful. From 1609 to 1621 there was a twelve-year truce between Spain and the Dutch Republic. England’s war with Spain ended in 1604, and France was recovering from a long civil war and a Spanish invasion (1562–1598). This peaceful period gave England, France, and Holland an opening to explore the possibilities of trade with North America.2

The Jamestown colonial project, as conceived by the Virginia Company, was initially planned to be both a settlement and a trading post. Raleigh’s first Virginia settlements (1585–1590) were undertaken as the English were learning how to finance and organize “colonial” settlements in Ireland. In 1607 some of the colony’s leaders had quite a bit of experience as both soldiers and traders in other parts of the world. They and the local Native Americans both knew that trade required consistent behavior and mutual trust. Unfortunately, despite the colonists’ good intentions, their leaders were military men who readily used force when frustrated.

The Jamestown colonists landed in an area where the Native Americans had only recently been hit by a major epidemic. When European settlers appeared in Virginia in 1607, the surviving Native American communities were trying to reorganize and consolidate their fragmented tribes. Many communities simply lacked the manpower to exploit what once had been their territory, much less drive away invaders. Weakened by disease and struggling to reintegrate their own society, the local Native Americans were led by a dynamic chief the English called Powhatan. He had organized about fifteen thousand survivors from about thirty small communities into a loose federation and could easily have eliminated the entire Jamestown colony. Powhatan, however, seems to have decided that he could integrate the colony into his network of alliances.3 He admired the English weapons and novel technology but considered their knowledge of gift giving and protocol to be poor.

The colony was entirely men, many of whom had extensive military experience in a variety of settings, though few knew much about farming. While the promoters hoped the colony would become a profitable trading post, it really began as a military installation intended to secure a safe base for future settlers. Dependent on England for their supplies and faced with erratic and often long-delayed deliveries, colonists barely survived some of the colony’s early years. Under the command of Captain John Smith, and at times desperate for food, the colonists alternated between negotiating with the Indians for food and conducting brutal raids that captured food stored by the Indians for their own use.

Despite John Smith’s aggressive behavior, Powhatan provided enough help in the early years to keep the colony alive.4 A handful of statistics tells the story of the first grim years of the colony. In 1610, after three years during which the colony imported nine hundred people, only sixty remained. In 1616, despite the arrival of 2,100 more settlers, the community had only 650 European inhabitants.5 Powhatan led a bloody but abortive raid in the early 1620s that killed a third of the colonists; his successor led another major revolt in 1644. By that time, thanks to disease among the Indians and immigration from Europe, the Indians were outnumbered and restricted to a number of small reservations.

The English had hoped to create trade relations with the Native Americans, and both sides knew that patience and trust were crucial to trade in the long run. Nevertheless, the military leaders of Jamestown badly mishandled their attempts to open trade with Powhatan, shifting back and forth between negotiation and force in order to obtain food and other supplies. Admittedly, the Native Americans had little to offer that the English regarded as valuable, but if relations had been handled differently, and the two parties could have coexisted more amicably, Jamestown would have suffered much less death and misery.

Powhatan’s bloody raid in 1622 convinced the English promoters that the colony could not survive on trade alone and that they had to find a way to produce a profitable export commodity. In 1611 one of the colonists developed a hybrid type of tobacco that grew well in Virginia. By 1617, when ten thousand pounds of tobacco were exported, Virginia was beginning to look like a promising plantation colony. This collective commitment to tobacco farming set the colony on a course that led to friction with neighboring Native American communities. As long as it had been run as a trading post, the colony needed only a limited amount of land, but that was to change as colonists and indentured servants began to clear land for tobacco farming. Once committed to cultivation of tobacco, the colony negotiated for, or simply took, more and more Indian land, dispossessing its indigenous owners.6 Inevitably this led to recurrent violence along what would become a steadily moving frontier.

Like sugar, tobacco was addictive and had a similarly elastic demand curve. Virginia’s tobacco exports went from ten thousand pounds in 1617 to fifty-five million pounds in 1775. In contrast to sugar, tobacco could be grown on plantations or on small family farms.7 A small farmer, however, was more vulnerable to weather or market changes than a large plantation owner. For the small farmer, a crop failure or a drop in the price he received for his crop easily put him in permanent debt. The owner of a plantation could survive a temporary loss because he could get credit in England based on future crops.

The tobacco plantations of Virginia faced the same difficulties maintaining a labor force that we saw in Brazil. In the early decades of the 1600s, the nearby Indians were well organized, making it impossible to capture and enslave them. Consequently, indentured servants provided most of the labor in the first decades of the tobacco era. If they survived their indenture and received the land promised in their contracts, they then became tobacco growers themselves.

Indentured servants proved hard to manage and more expensive than slaves. As of 1650 Virginia had 18,700 people, half of them indentured servants, but only four hundred African slaves. As the plantation economy expanded during the second half of the seventeenth century, the number of African slaves rose faster than the white population. In 1700 Virginia had fifty-eight thousand inhabitants, seventeen thousand (or 30 percent) of whom were slaves. The more northerly colonies also used slaves, and in 1750 northern English America, from Pennsylvania to Massachusetts, had a total of almost twenty-five thousand slaves.

Slavery did not end the use of indentured servants as a source of controlled labor. By the time of the American Revolution, the population of the thirteen colonies was about 2.4 million inhabitants, and about half a million (roughly 20 percent) of them were African slaves. About five hundred thousand people had moved to the American colonies from Europe; about three hundred thousand of them came as indentured servants.8 They arrived committed to work three to five years for whomever held their contract of indenture. While they were not regarded as slaves, their working conditions were little better than those imposed on slaves. The fact that 40 percent of indentured servants died before finishing their contracts certainly suggests that their working conditions were like those of many slaves.9

As of 1775 Virginia was by far the largest of the thirteen colonies, with more than 450,000 people. Less advertised is the fact that African slaves accounted for 41 percent of that total, twice the percentage of the thirteen colonies combined. Of the remainder, a sizable part of the white European population consisted of indentured servants. Virginia had become a society consisting of a dominant plantation-owning oligarchy, a huge slave population, and a class of European small farm owners who had nothing to say in colonial government.

As suggested at the beginning of this chapter, the New England colonies followed a different and, as of the early seventeenth century, unique path. The settlers at Plymouth and Boston were religious refugees intent on creating a European-style agrarian society where they could control their own religious and political affairs. The colony’s organizers had done serious advance planning. In 1614 they commissioned Captain John Smith, veteran of the Jamestown project, to survey the Atlantic coast and identify potential sites for the new colony. When the Pilgrims arrived in 1620, they reviewed the preselected locations and settled on the site of an abandoned Indian village.

The Pilgrims at Plymouth settled in an area where earlier epidemics had killed most of the indigenous peoples. The surviving Indians had abandoned the site and merged with another community. The site the Pilgrims chose had been cleared by its previous users, was in an easily defended position, and was near open fields the Indians had prepared for planting before the epidemic. Arriving late in the year, the colonists were forced to spend their first winter living in miserable conditions on the Mayflower while building houses onshore. The colonists would not have survived at all without the help of the neighboring Pokanoket community. In an unlikely encounter, the Pilgrims met a Native American named Squanto. Squanto had spent some years in England and had recently persuaded the captain of an English fishing ship to drop him off not far from the Plymouth landing site. Despite Squanto’s mediation, by spring, bad food, winter weather, scurvy, and related diseases had killed 45 of the original 102 settlers.

The Pilgrims were followed by the Puritans, a much larger group of settlers who founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony and Boston. The first four hundred of that group arrived in 1628–1629, while the main contingent of seven hundred colonists and a fleet of twelve ships arrived in 1630. This was the beginning of a flood of ten thousand new colonists over the next ten years.

The need for additional farmland and the tension between the settlers and the Native Americans of the area increased as the European population of Plymouth and Boston grew from about eight hundred people to more than ten thousand in a decade. The first colonists had negotiated treaties for land use, a process that worked well when the colonial population numbered in the hundreds. As the population reached several thousand, the colonial appetite for land grew beyond what could be acquired with treaties.

The colonists grew increasingly impatient with the Indian concept of land ownership. The Indians considered the land to be the collective property of the community and thought in terms of leasing or selling specific ways of using the land. This included sharing what the land produced in ways that were alien to European ideas of property. As the colony grew, the settlers paid less and less attention to Indian land rights and to their own promises to the Indians. A series of incidents escalated into what has been labeled the Pequot War (1634–1638). The English settlers systematically organized an attack on a major Indian town. At the time of the attack, the men of the town were away on a hunt and the town contained only women, children, and a few old men. Despite that fact, the colonists surrounded the town, set it on fire, and systematically killed anyone who tried to escape.10

Except for the bloody Pequot War, most of the period between 1607 and 1675 saw an uneasy coexistence between the New England settlers and their Native American neighbors. As more farm families arrived, however, the colonies appropriated more and more Indian land for farming, progressively alienating the nearby Indians and undermining the comity between Native Americans and invading Europeans.11 By the 1670s the settlers were self-sufficient and no longer experienced the food shortages that made them grateful for Indian help. Disputes over land use and land ownership surfaced more readily. As New England expanded after 1675, the colonists appropriated more and more land, triggering recurrent bloody clashes.

By 1710 colonial perceptions of Native Americans had altered dramatically. Indians living in or near European settlements became suspect and were forced out. Skin color emerged as an identifier of race, and for the first time, Indians were identified as “red.” By 1740 colonial America had a hierarchy of races and their relative abilities; everyone was white, red, or black, in a descending order of racial abilities.12

Meanwhile, Boston had become New England’s leading commercial center. By replicating agrarian Europe in America, the Puritans were left with very little to sell to Europe. At the same time, the colonists needed European manufactures to maintain their lifestyle and had to figure out how to earn the foreign exchange they needed to pay for the products they imported from England.

The solution came with the evolution of the Brazilian, Caribbean, and colonial American economies. As we have seen, Spain had loosened her hold on the Caribbean in the 1620s and 1630s, and the Dutch, English, and French took over many of the islands. The English captured Bermuda, Barbados, Nevis, St. Kitts, and Jamaica; the French took part of St. Kitts, Guadeloupe, and Martinique.13 The smaller islands were first settled with indentured servants who were used to raise tobacco. As sugar replaced tobacco as the most profitable crop, the tobacco farmers migrated to Virginia and North Carolina.

Meanwhile, the Caribbean sugar plantations became so specialized that they stopped producing their own food and fed their slaves with imported flour, wheat, and rice, all of which came from the colonies of Atlantic North America. Thus, the northern colonies’ agricultural surpluses coincided with the growth of highly specialized plantation economies in the southern colonies and in the Caribbean. Plantations specializing in sugar, tobacco, and cotton found it cheaper to import food for their workforce than to try and produce it locally. Merchants in the northern colonies traded their wheat and flour for sugar and molasses. The molasses was distilled into rum that they sold in England. As trade connections like this multiplied, New England, with plentiful timber, began to build the ships required to move the goods being exchanged. By the time of the American Revolution, as much as a third of England’s merchant ships had been built in Atlantic North America.

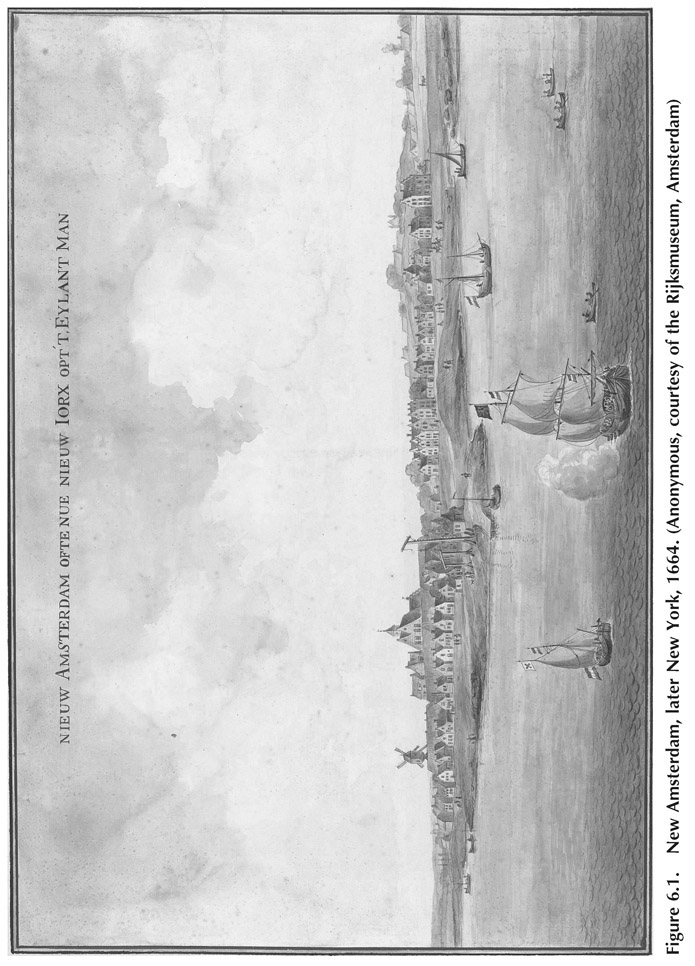

From their first contacts with North America, the Dutch planned their settlements as adjuncts to the fur trade. In 1609 the Dutch hired Henry Hudson to explore the northern parts of the North American coast, and as part of the project he sailed up the Hudson River as far as modern Albany. Hudson reported that the natives were both friendly and eager to trade furs for European goods. The Dutch followed up on Hudson’s report and in 1614 built Fort Nassau near modern Albany. Founded by the Dutch West Indies Company, the colony was under Dutch control for only fifty years before it was ceded to the English in 1664. Fort Nassau was built as the focal point for Dutch development of the fur trade, primarily with the Iroquois. Over the next decade, small Dutch villages were founded near Fort Nassau and in the vicinity of the seaport of New Amsterdam (later New York) in the hope they would be able to supply the two towns with food.

In 1624 the Dutch formally established the province of New Netherland, claiming jurisdiction over much of the modern states of New York and New Jersey. The population of New Netherland grew very slowly, reflecting the Dutch West India Company’s lack of interest in sponsoring a European agricultural community. Its single-minded focus on the fur trade is suggested by the fact that in 1630, sixteen years after building Fort Nassau, the entire colony of New Netherland counted only three hundred settlers. Twenty-five years later, in 1655, the population of the entire colony was only about three thousand. Most of them lived near New Amsterdam. Only a few settled in the Hudson River Valley.

New Netherland was distinctive because, except for one incident, the tiny Dutch settlements along the Hudson coexisted amiably for twenty-five years with the Indians of the region. Between 1630 and 1660 Fort Nassau and nearby villages lived among, and were vitally dependent upon, neighboring Indian communities. Indian farmers sold food crops to the Dutch in return for pots, pans, knives, gunpowder, guns, and a variety of trade goods. The Native Americans were also dependent on this collaboration because as the fur-bearing animals in the area around Fort Nassau were trapped out, the local Iroquois became middlemen between the Dutch and more distant Indian communities. They needed a supply of European trade goods to trade with these communities, which still had a supply of furs.

This equilibrium was interrupted briefly in 1639–1643, when an ill-advised Dutch governor triggered a revolt by attempting to tax the nearby Indians as though they were Dutch subjects. The Indian community forced the governor to rescind the tax, after which the Hudson Valley enjoyed two peaceful decades in which Dutch settlements and Native American communities lived side by side. Coexistence worked in part because the colony continued to grow very slowly. As late as 1664, when it was surrendered to the English, all New Netherland counted only nine thousand Europeans.

The Dutch colony and the neighboring Indian towns developed a complex, almost symbiotic relationship. Dutch authorities discouraged sexual relations and intermarriage with Indians, but such social control was less effective among the soldiers and trappers who lived on the edges of colonial society.14 Individuals from both communities did form person-to-person business agreements, and Native Americans moved freely around the Dutch towns to transact business. If the business was transacted with a Dutch family, the Indian participants in the transaction routinely slept overnight in the family home, a form of hospitality that was reciprocated when the Dutch visited nearby Indian communities. The Dutch had mixed feelings about close contact with the Indians, mostly because of Indian ideas regarding good manners and hygiene. The Indians apparently had similar feelings and found the Dutch insulting, brusque, and stingy.15 Yet the relationship was part of a pervasive network of mutual dependence that the Dutch found uncomfortable but necessary.

The Dutch dealt primarily with the Iroquois. But in the 1660s the Iroquois had long since trapped out the hunting grounds near Fort Nassau and, as noted, were using European trade goods to buy furs from more distant Indian communities. By the time the English took over New Netherland in 1664, the Iroquois controlled most of the fur trade in New York and Pennsylvania. With the Dutch out of the picture in New York, France and England now confronted each other in frontier areas between New York and French Canada and in the Ohio Valley south of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie.

The Iroquois dominated the frontier area covered by the French and English territorial claims, and they had a large enough army to command the respect of any European forces in the area. With the departure of the Dutch, and depending on your perspective, the Iroquois became either the allies or the victims of the English. England’s recurrent wars with France in Europe were projected onto the American frontier.16 The Iroquois allied with the English in hopes of retaining control of the fur trade, but they had to reach farther and farther west to trade with Indians who still had a supply of furs. Meanwhile, New York, the former New Netherland, was recruiting more and more settlers and appropriating Iroquois land, undermining what had been a stable relationship between the English and the Indians.

In 1608, only a year after the English planted their first permanent settlement at Jamestown, a small group of Frenchmen moved into Canada and founded Quebec City. The contrast with Brazil is striking. The Portuguese in Brazil avoided the interior and used plentiful land, imported capital, and slaves to create an externally focused economy based on sugar. By contrast, the French in North America ventured deep into the continental interior to mobilize the trade in furs, setting up a system of paternalistic trade and gift giving that created and maintained good relations with the Indians. In the process, the French drew the Native American population into a trade network that reached from the Saint Lawrence River to the western shore of Lake Michigan and the shores of Hudson Bay.

French ships had been visiting the Saint Lawrence River since Jacques Cartier’s explorations in the 1530s, regularly negotiating treaties with the Native Americans and trading for furs. The city of Quebec was founded in 1608 as a permanent base for the fur trade and, with Montreal and the fort at Detroit, became the framework for the French fur trade. These settlements were supplemented by a number of smaller trading posts convenient to the Native American communities with which the French traded. The French network of small trading posts was supplemented by treaties with the Indian tribes of the Ohio River Valley and Great Lakes, reaching as far west as Wisconsin—treaties the French were careful to honor.

As the French and English in southern Canada and the Ohio Valley began to compete for the fur trade, the Indian tribes began to fight for access to European agents and their trade goods. The French started by developing a trade relationship with the Huron Indians located in Canada north of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie and east of Lake Huron. As Huron territory was trapped out, the Hurons became middlemen between the French and more distant tribes. The Iroquois had been trading with the Dutch at Fort Nassau until 1664, when the English replaced the Dutch. Supported by the English, the Iroquois repeatedly attacked both the French and the Hurons, and by the end of the 1660s, Iroquois attacks had wiped out the Hurons. The Iroquois, meanwhile, continued to help the English fight the French.17

At the same time, European diseases were hitting the Indian tribes in the region. That and conflicts between tribes over parts of the fur trade dislocated several Algonquian-speaking Indian tribes from the Ohio Valley and the southern part of what is now Ontario Province. Several thousand of these refugees moved to northern Illinois and Wisconsin, where their leaders tried to gather the fragments of several tribes into a new and coherent community.18

The French governor in Detroit responded by developing a policy of acting as a benefactor and donor, providing European trade goods and sometimes food supplies to the refugee Algonquian tribes. In return the Indians kept furs moving toward Detroit, Quebec, and the agents for the French fur trade. As they trapped out the fur-bearing animals in the areas they controlled, the Algonquians became middlemen or brokers between the French and the Indian communities living in more distant areas where fur-bearing animals were still plentiful.19

The French attempt to control the Great Lakes region evolved into a complex exchange with Indian communities on both sides of Lake Michigan. Based on mutual understandings conveyed by symbolic gestures, gift exchanges, and verbal formulas, this “middle ground” allowed Native Americans and French agents to settle diplomatic, judicial, and commercial disputes while exchanging Indian furs and foodstuffs for European tools, weapons, tobacco, and cloth. This relationship remained stable for almost a hundred years. It included various ways of settling disputes, but it was never tested as a way of negotiating transfers of Indian land to European settlers, something the French consciously avoided.20

This trade network was supplemented by what may have been as many as several hundred roving trader-trappers, or coureurs de bois. These men were independent traders who spent much of the year living with or moving between the more distant Indian communities, buying and trapping furs. When the season was over, the furs they had collected were brought by canoe to Quebec.

Although to European eyes these trappers were loners, they actually made up a community of several hundred men. Most of them married, or had long-term relationships with, Indian or mixed-race women. The women of this community, along with their children, were victims of growing racial prejudice in the eighteenth century as New France began to attract a significant number of European women.21

By the 1660s, when the French fur trade had been in place for some time, a group of English promoters pieced together an understanding of the sketchy geographic information available about northern North America. They realized that they were missing an opportunity and in 1668 sent out an experimental voyage to Hudson Bay. The expedition founded a small trading station and fort at York on the southwest shore of Hudson Bay and returned with a profitable load of furs.22 This prompted the foundation of the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1670. The company made no attempt to actually colonize the Canadian north, nor did they send out the roving trappers that were part of the French trade network. Instead they maintained buyers or agents at a small selection of permanent trading stations where the buyers simply waited for the Indians to come to them. They offered favorable prices and an escape from the tension between the French and the English farther south. The Hudson’s Bay Company soon attracted a growing list of Native American communities to its company outposts.

The geographic scope of this trade in an era of foot travel and canoes is hard to grasp. The York station was visited by Indian traders from as far away as what is now central North Dakota. Archaeological evidence shows that the Indians of that region in turn had had trade connections that reached Minnesota, the Gulf Coast, New Mexico, and what is now Washington and Oregon since the middle of the 1400s.23

On at least two occasions, the French tried to capture the English trading post at York but were driven off. The logistics of organizing and mounting an attack on a fortified trading post that was more than two thousand miles by lake, stream, and portages from Quebec were beyond the resources of the French authorities. The English of the Hudson’s Bay Company were commercially successful in part because they did not use roving trapper-traders and because they deliberately avoided any participation in disputes between competing Native American communities. In this way they maintained an aura of neutrality and peace around their stations, where Indians from otherwise warring tribes did their business side by side. That aura was very effective in attracting Indians who wanted to trade.

French Canada, meanwhile, gradually became something more than a series of trading posts, since it also included a slowly growing colony of French settlers. Quebec was a small, miserable place, even by seventeenth-century standards, and included virtually no European women. Ten years after being founded by twenty-eight men, Quebec City had barely one hundred inhabitants. As in other distant outposts, resident Frenchmen took Indian women as partners or wives. The French authorities encouraged this, on the theory that the Indian wives would adopt their husband’s French culture—language, attitudes, and religion. Predictably, mixed-marriage households embedded in Canada’s indigenous culture actually adopted Native American customs and family relations. When, in the eighteenth century, attitudes toward Indians became negative, the offspring of French colonists and Native American women experienced the same rejection by European society as the offspring of the roving coureurs de bois. By contrast, Native American communities readily integrated both renegade white colonists and mixed-race children into their society.

The colony’s slow growth and its emphasis on the fur trade allowed the French to maintain stable relations with the Native Americans. Quebec did not reach five hundred inhabitants until after 1663, when all French Canada had only three thousand European inhabitants. During the seventeenth century, about fifteen thousand Frenchmen migrated to Canada, but half of them either died or returned to France. The slow rate of growth and the concentration on the fur trade created little friction with the Native Americans over the actual control of land, and the fur-trading network lasted well into the eighteenth century. From a global perspective, the fur trade tied an otherwise isolated and inaccessible area amounting to one-third of all North America into the global commercial network.

In sum, Europeans typically arrived on the shores of North America in small numbers, poorly equipped, short of supplies, and suffering from the effects of a long voyage.24 The Native Americans they met were equally handicapped because they were coping with the effects of devastating epidemics. The natives were curious and willing to extend hospitality to strangers, a tradition that saved many European colonists from starvation.

Land was the underlying source of conflict between colonists and Indians, while furs and deer hides sustained a long-term commercial collaboration. This is why French Canada enjoyed prolonged, stable relations with the Indians. In contrast, as agricultural colonies grew, they appropriated ever more land, undermining Native American communities and prompting them to violence to protect their land.25

The irony is obvious. Native Americans provided the food that kept the early settlers alive. Their participation in the fur trade helped pay the early costs of establishing the colony. The next cohorts of colonists repaid the Native Americans by appropriating lands that were part of the Indian way of life. The progressive and permanent appropriation of Native American land undermined any stable relationship between Native Americans and European invaders.

Once the survival of a colony was assured, the next problem was to find something profitable to send home to the people who invested in the colonial project. In North America, French, Dutch, and English investors were first attracted to the rich supply of furs discovered through early contacts with coastal Indians. When the French entered Canada by way of the Saint Lawrence River, they found indigenous trade networks already in place. When they saw it was to their advantage, the Indians adjusted their activities and began exchanging furs for European manufactures. As successive hunting grounds were trapped out and dislocated tribes settled in the upper Midwest, the fur trade became more complex. Tribes near the French forts became commercial middlemen, trading European goods for furs trapped by more distant communities.

As a result, the global commercial network was extended deep into the seemingly isolated center of North America, following age-old indigenous trade networks. The long-term outcome of this commerce left the Indians dependent on a supply of European manufactures they could not make for themselves. Once the fur-bearing animals were trapped out, the Indians became vulnerable to European exploitation.

Virginia, and later Maryland and North Carolina, quickly specialized in the production of tobacco once a viable hybrid was available. South Carolina became a major exporter of rice to the plantations in the Caribbean. The irony in that case is that plantation owners learned how to produce rice from slaves imported from the Caribbean. Many of those slaves had learned these techniques in Africa before being sold into slavery.26

In Pennsylvania and New York, the new farms soon produced surpluses of wheat and other agricultural foodstuffs, goods for which there was no market in Europe except in cases of extreme shortages.27 As farming in Virginia and the Carolinas became more specialized, those colonies imported food from Pennsylvania. Farther south, in the Caribbean, the same process of specialization created markets for foodstuffs from the Atlantic colonies. Their ships returned to New England with sugar and molasses. The molasses was distilled into rum, giving New England a product with a ready market in England. By 1700 the shores and seaports of the Americas, Africa, and Europe were tied together by a network of maritime connections—a network more complex than the “triangular trade” of many textbooks. This New World economic zone was crossed by countless cargos of sugar, tobacco, European manufactures, wine, coffee, cacao, indentured servants, gold, silver, and slaves. Within this Atlantic framework, sugar and tobacco, for which Europe had an insatiable demand, played an important role in integrating intercontinental trade in the Atlantic, a role that was similar to that of silver in Eurasian trade.28