Lord George Gordon MP, leader of the Anti-Popery protests, encouraging the mob to enter the Houses of Parliament in June 1780; left The burning Catholic chapel of the Sardinian Embassy; far left Lord Stormont being assaulted in his coach for voting in favour of the recent Catholic Relief Bill. French engraving of the Gordon Riots (once in the collection of the Catholic writer Hilaire Belloc).

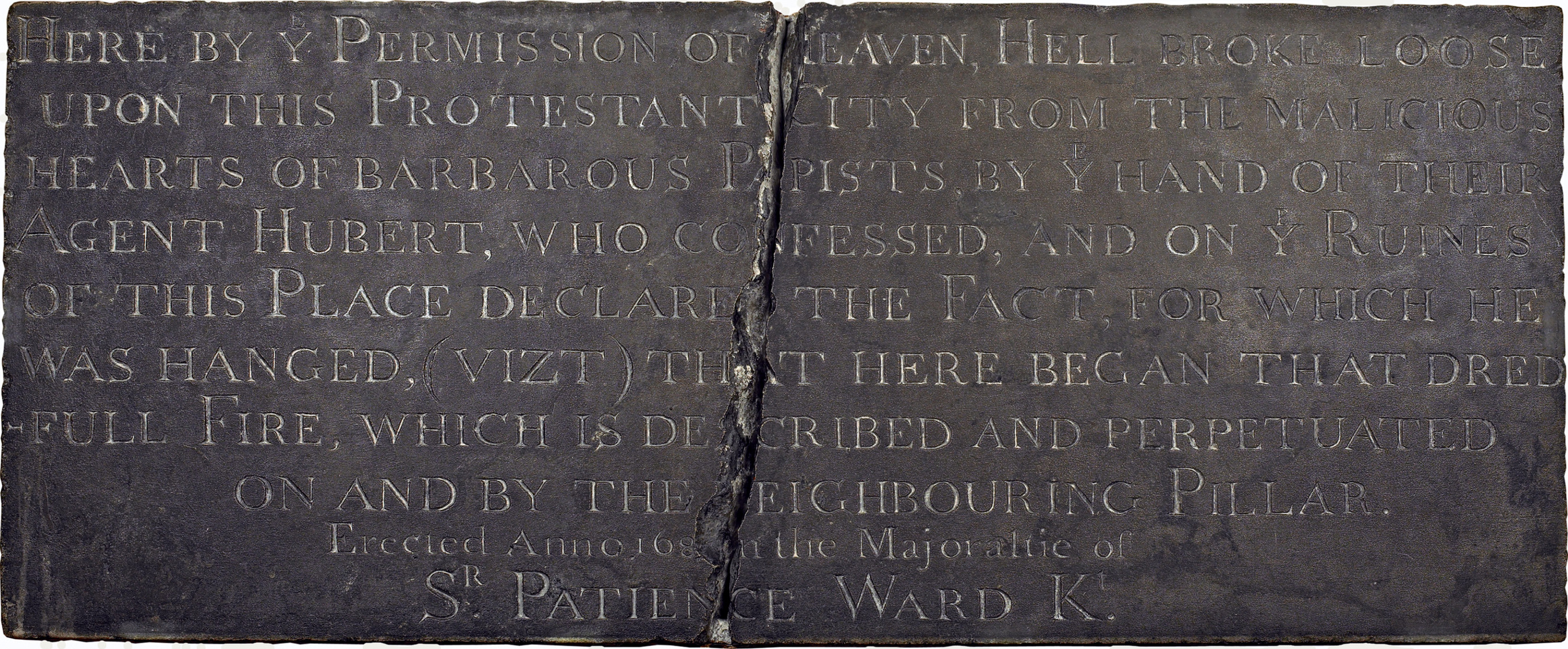

Plaque commemorating the Great Fire of London in 1666 put up on the house where it started in 1681, blaming the Catholics: ‘Here by ye permission of heaven, hell broke loose upon this Protestant city from the malicious hearts of barbarous papists…’; taken down in the reign of the Catholic James II, then reinstated; now in the Museum of London.

The chapel at Lulworth Castle, Dorset, built by Thomas Weld in 1786 at a time when Catholic churches and chapels were technically illegal, so that most chapels were concealed within country houses. George III was said to have suggested with a wink to his friend Weld that it was actually a mausoleum which was taken by Weld to be ‘a kind of sanction’.

Charles 11th Duke of Norfolk by Thomas Gainsborough. A flamboyant character, he was ostensibly a Protestant despite being the head of the leading Catholic family of Howard, on the grounds that he wanted to take his seat in Parliament: ‘I cannot be a good Catholic…if a man is to go to the devil, he may as well go thither from the House of Lords…’.

King George III, 1810–15, by Edward Bird.

Robert Edward 9th Baron Petre. A Catholic grandee, famously benevolent, who was an early advocate of Emancipation. He was also able to be Grand Master of the Masonic Order in the days before Catholics were forbidden to be Freemasons. Cardinal Manning later observed that the Catholic Church was built on the foundations of Lord Petre as well as St Peter.

‘A Great Man at his Private Devotion’, 1780. George III, who assented to the Catholic Relief Bill, shown as a tonsured monk with the implication that he was a secret Catholic.

Cardinal Ercole Consalvi, who came to London from Rome for the Congress of 1814, the first official visit by a Cardinal since the sixteenth century; a man of great personal charm and culture, he enjoyed enormous social success, including with the Prince Regent who described Consalvi lightly as ‘Cardinal Tempter’.

Thorndon Hall, Essex, seat of Lord Petre, where despite his Catholic religion he entertained King George and Queen Charlotte lavishly in October 1778, to demonstrate his loyalty.

An imaginary scene at Thorndon during the visit, to satirize the royal presence in a Catholic household, with Grace being said by a priest standing at the head of the table. Subtitled ‘a Peep at Lord Peter’s’.

Maria Fitzherbert, the Catholic widow who won the love of the Prince of Wales, and went through a form of marriage with him which was not valid in English law under the Royal Marriages Act 1772.

Henry Grattan, the Irish Protestant MP who represented Dublin City in the British Parliament and campaigned actively for Emancipation.

‘The Apostates and the Extinguisher’, 1829. The Duke of Wellington kissing the Pope’s toe. The Duke swears with all humility to ‘conform to the will of your Holyness’; the Pope hands over his diadem (the Papal tiara) for the extinction of heresy in Britain so that ‘our true Catholic faith shall again govern your country’.

Bishop John Milner, a forceful character – he was noted for his ‘asperity’ – who denounced the idea of a ‘Veto’ by which the Protestant sovereign could ban the appointment of individual Catholic bishops.

George IV, who finally succeeded as King on his father’s death in 1820, having been Prince Regent since 1811, by Sir Thomas Lawrence. A suitably royal image in contrast to the mockery of the cartoonists.

The Coronation of King George IV in Westminster Abbey, 19 July 1821; he took the Oath which pledged ‘a binding religious obligation’ to maintain the Protestant religion that came to dominate his conscience.

‘A Voluptuary under the horrors of digestion’. The self-indulgence of the Prince of Wales, later Regent and finally King, led to the early deterioration of his appearance from the handsome looks of his youth. James Gillray, 1792.

Elizabeth Marchioness Conyngham, the royal mistress. It was said that the King had never known what it was to be in love before: he was seen nodding and winking in her direction at the Coronation.

George IV in Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street), Dublin, amid cheering crowds, in August 1821. It was the first royal visit to Ireland since Richard II in 1399.

Sydney Owenson Lady Morgan, the Protestant novelist, with a strong feeling for Irish nationalism; author of the bestseller The Wild Irish Girl, 1806.

Richard Marquess Wellesley, elder brother of the Duke of Wellington, who married a Catholic as Viceroy of Ireland, in a ceremony performed by the Catholic Archbishop of Dublin to the disgust of George IV. His liberal sympathies for the Irish, which resulted in great popularity, led to his eventual recall.

Daniel O’Connell in 1820 when he was forty-five; his dramatic appearance in his swirling cloak was an important part of his charisma.

Daniel O’Connell’s house in Merrion Square, Dublin.

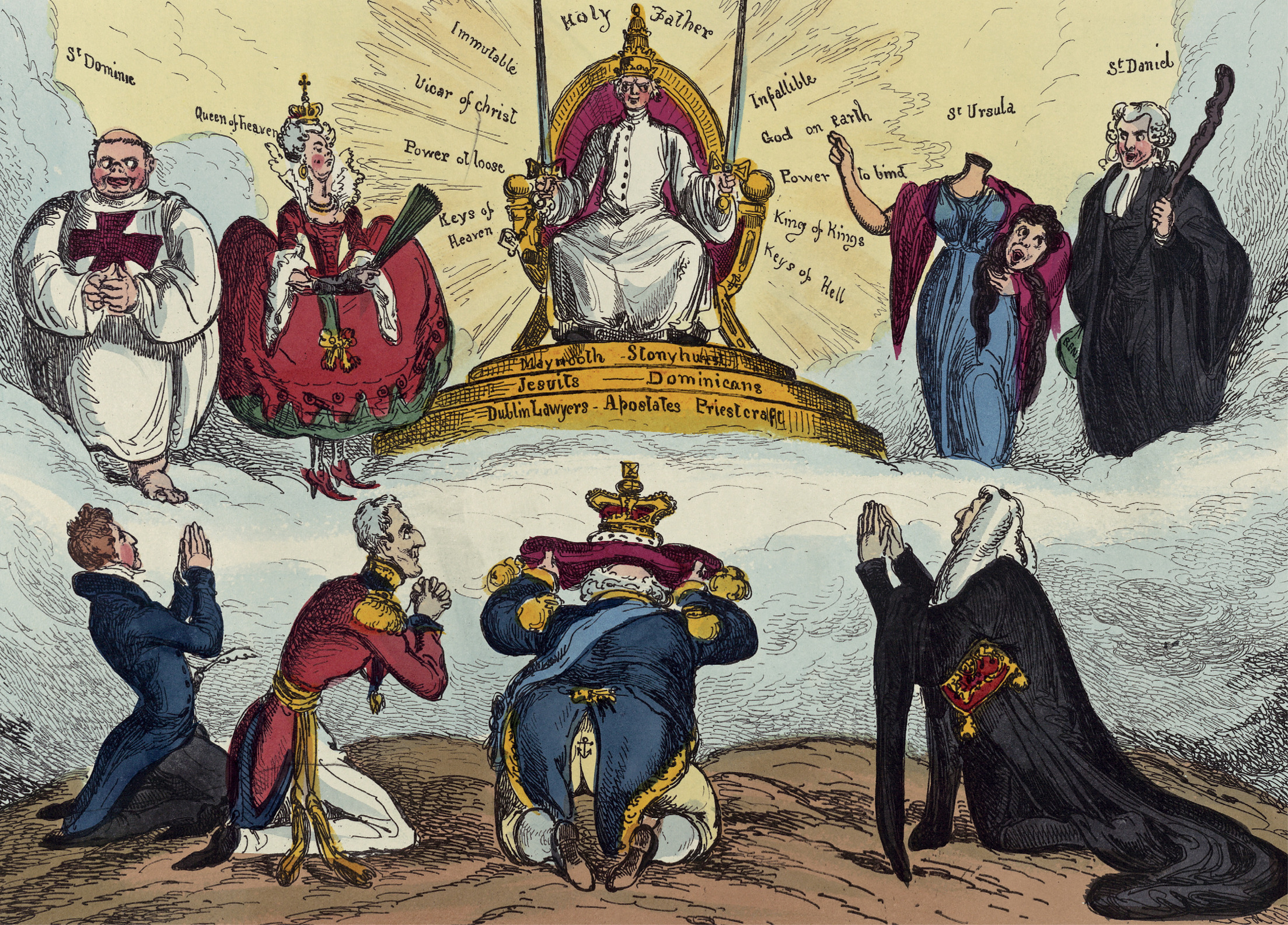

‘How to keep one’s place.’ British politicians, including Wellington, kneeling before the ‘Holy Father’ surrounded by saints, and offering him the crown; on the steps of the Pope’s throne are significant Pro-Catholic words including Maynooth, Stonyhurst, Jesuits and Dublin Lawyers.

Brunswick Tom: Thomas 2nd Earl of Longford, a vigorous opponent of Emancipation who founded the Irish Brunswick Club.

Bernard 12th Duke of Norfolk, a zealous Catholic. He was painted wearing his Parliamentary robes to celebrate the passing of the Act for Emancipation which enabled him as a Catholic to sit at last in the House of Lords.

Daniel O’Connell’s statue erected in Ennis, Co. Clare, to mark his election for the British Parliament at the Clare by-election in the summer of 1828 (despite being a Catholic).

‘The Field of Battersea’: caricature of the duel fought there between the Duke of Wellington when Prime Minister, and the Marquess of Winchilsea, vociferous opponent of Emancipation, on 21 March 1829, shortly before the passing of the Act. The Duke reflects that he used to be a good shot but has been out of practice for years; Winchilsea decides to make himself small, fearing that if he is hit he may be tainted with some of Wellington’s popery.

Arthur 1st Duke of Wellington, 1829, by Sir Thomas Lawrence.

‘The Battle of the Petitions’. Subtitled ‘a Farce now performing with great applause at both Houses’, 1829. Numerous petitions from the country, both Pro- and Anti-Catholic, were presented by MPs and peers to Parliament.

No Peel: a protest hammered into a prominent door in Christ Church during Sir Robert Peel’s unsuccessful attempt to be re-elected for Oxford in February 1829 after he changed his mind about Emancipation; Christ Church was Peel’s old college.

Sir Robert Peel in 1829.

The Duke of Wellington is seen proffering a sickly John Bull with various objects including the Bill for Catholic Emancipation and Price List for Indulgences, a crucifix, rosary and a dagger, with Peel carrying the column put up to commemorate the alleged Papist origins of the Great Fire of 1666 and Eldon as a doctor. John Bull protests: ‘I shall never be able to get this down – my Constitution is very much impaired…’.

‘Leaving the House of Lords Through the Assembled Commons’, 1829. Wellington gallops home triumphantly on leaving the House of Lords after a successful vote for Catholic Emancipation, while the mob yells, ‘No popery – No Catholic ministers’.