KEY OF C, KEY OF G, KEY OF E

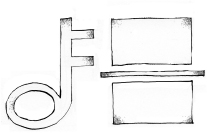

Grandpa Rose’s cheeks were tattooed with shaky bluish writing. One cheek said PAWPAW ISLAND THERE BOTTLED SHIPS BONES FROM BOW NINE PACES INLAND under a symbol of a key. One cheek said X18471913 under a symbol of a box.

My brain said 18,471,913 = prime.

“I tattooed myself while the kid was sleeping,” Grandpa Rose (forte)said.

Grandpa Rose peered into the cloudy mirror above the sink, poking his cheeks with his fingers. We stood around him, in the light of the lantern, staring at the tattoos. Grandpa Dykhouse was gripping the whiskery scissors he had used to trim the beard to stubble, the foamy razor he had used to shave the stubble to skin.

Grandpa Rose poked the symbol of the key.

“We’re looking for a key,” Grandpa Rose (forte)said.

“A key to what?” I (forte)said.

Grandpa Rose poked the symbol of the box.

“A trunk. A dark trunk. A dark trunk with a brass lock,” Grandpa Rose (forte)said.

“The heirlooms are in a trunk?” I (forte)said.

“I remember a dark trunk with a brass lock,” Grandpa Rose (forte)said.

“So we need to find the key and then the trunk?” I (forte)said.

“Yes,” Grandpa Rose (forte)said.

“What’s PAWPAW ISLAND?” Jordan (forte)said.

“I don’t remember,” Grandpa Rose(mezzo-forte) said.

“THERE BOTTLED SHIPS?” Zeke (forte)said. “BONES FROM BOW?”

“I don’t remember,” Grandpa Rose (mezzo-piano)said.

“NINE PACES INLAND starting where exactly?” I (forte)said.

“I don’t remember,” Grandpa Rose (piano)said.

“Couldn’t the tattoos have been more specific?” I (fortissimo)shouted.

“Calculator, relax, do you know how much being tattooed hurts?” Jordan (forte)said.

“You can’t write itemized instructions if you’re writing on your skin,” Zeke (forte)said.

They seemed awestruck that Grandpa Rose had actually tattooed himself. I hadn’t thought about how much that would have hurt. Especially on his face.

“Every word would have mattered,” Grandpa Dykhouse (mezzo-piano)whispered.

I touched the tattoo, X18471913, under the symbol of the box. Some large primes are so massively powerful that using them is illegal—you can use them to unlock government codes, or computer programs, or other things you aren’t supposed to. That’s what 18,471,913 was like. An illegal prime. One number that could unlock everything.

Grandpa Rose was (pianissimo)mumbling to himself again, hunched over his cane.

“If you want to find these heirlooms, you’ll need to learn everything about Monte’s life that you can,” Grandpa Dykhouse (forte)said. “I’ll keep logging his memories. I’ll make note of every name, every word, every number. The meaning of the tattoos might become plain once you understand his roots.”

“King Gunga is unstoppable in librarian mode,” Jordan (forte)bragged.

“We still don’t know if the heirlooms are worth anything,” Zeke (forte)said.

“Why would he have tattooed himself if there wasn’t anything worth coming back for?” I (forte)said.

Zeke uncapped a silver marker. He wrote PAWPAW ISLAND THERE BOTTLED SHIPS BONES FROM BOW NINE PACES INLAND between drawings of a mermaid leaping toward his elbow and a mermaid swimming toward his wrist.

“Aren’t you worried that your arms won’t look as pretty now, Boylover?” Jordan (forte)said.

“If you write something on your skin, it sinks in eventually and becomes a part of you,” Zeke (forte)said.

Jordan pointed at Grandpa Rose.

“That didn’t work with those tattoos,” Jordan (forte)said.

We split in the woods, each heading home through a different thicket of darkened trees. Once I was alone, I tightened the straps of my backpack and ran home at a breakneck tempo, taking shortcuts between garages and through backyards. The wind crept behind me from house to house, chimes (pianissimo)jingling in the key of C, unlatched doors (piano)knocking in the key of G, the lids of garbage cans (forte)thudding and (fortissimo)clattering in the key of E. Pairs of eyes, pairs of pairs of eyes, blinked in the trees. I felt nervoushunted. My house was dark except for a single window.

As I rounded my house, I took my violin from my backpack and plucked notes at my brother.

SORRY, IN A HURRY, GOODNIGHT FOR NOW! my song said.

I tucked my violin into my backpack and hopped the railing onto the deck.

With the wind in his branches my brother said, SOMEONE’S LAUNDRY HAS BLOWN INTO OUR YARD AND GOTTEN STUCK ON MY LIMBS.

I stopped. I spun around. I dropped my backpack and hopped the railing again and ran across the grass and the dancing shadows to my brother the tree. A sheet was caught halfway in his branches. The sheet (mezzo-piano)snapped with the wind, like the sail of a boat. I yanked the sheet down and ran into Emma Dirge’s backyard and pinned the sheet to the line there.

I FEEL BETTER, THANK YOU, GOODNIGHT, my brother’s song said.

I hopped the railing again and grabbed my backpack and shoved through the door.

Our house smelled like chemicals. The windows were gleaming. The wood of the piano was darker, less dusty than it had been, and its keys were white as bones. My mom was (mezzo-piano)humming to herself and mopping the floor. Where she was stepping, the floor was marked with footprints, like the blueprint of a dance. When she was a kid she was a dancer, and she still moves like one. Dancing is her music, her math, the language she speaks. She has books of dance choreography, ballet scores written in symbols only dancers understand. It’s like the X’s and O’s on the locker room’s chalkboard, the X’s and O’s that only the Isaacs and other basketball players understand, the X’s and O’s that tell them how to score.

“Where were you?” my mom (mezzo-forte)said.

“Outside,” I (forte)said.

“Your dad called while you were out,” my mom (mezzo-forte)said.

I wrenched off my high-tops, then crossed the kitchen, stepping from footprint to footprint.

“Why are you cleaning everything?” I (forte)said.

“We’re doing a showing of the house tomorrow,” my mom (mezzo-forte)said.

I froze.

Here was what could happen, from bad to worst. Bad was “a showing”—this meant that families that wanted to buy a house would come visit ours. Worse was “an offer”—after a showing, if a family liked our house, they could make an offer of however much money they were willing to pay. Worst was “a closing”—if my parents agreed to the offer, everyone would sign official paperwork, and that’s when we would have to leave the house and my brother forever.

A showing didn’t mean things were hopeless. But things hadn’t been this bad since my mom had planted the FOR SALE sign in our yard.

“Hey, kiddo, you look pale. Do you feel okay?” my mom (forte)said.

“I feel normal, I feel great, I feel 100%,” I (mezzo-forte)said. I unfroze. I ran to my room and (forte)shut my door and dumped all of my clothes onto the floor, socks and jeans and sweatshirts and jackets, like a pile of boys who had vanished. I (mezzo-piano)bent the window blinds. I took my knife and climbed onto my bed and (piano)scraped paint from the walls. I wanted my room to look messy. I wanted my room to look unlivable. I wanted whoever came through the house for that showing to think, I wouldn’t want to live here.