The Great Sectarian Revolts of the Late Cold War, 1975–1990

The Great Sectarian Revolts of the Late Cold War, 1975–1990

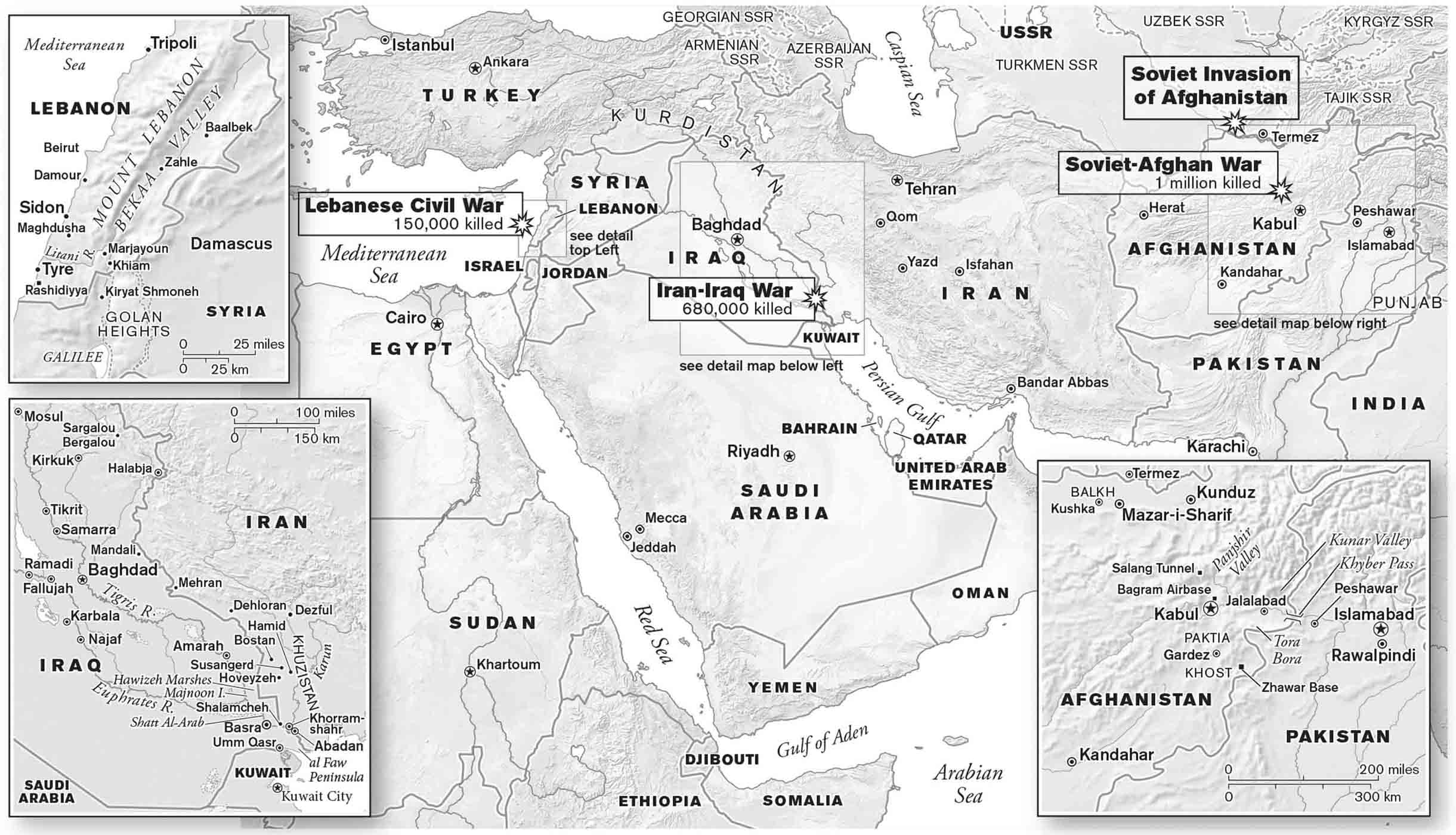

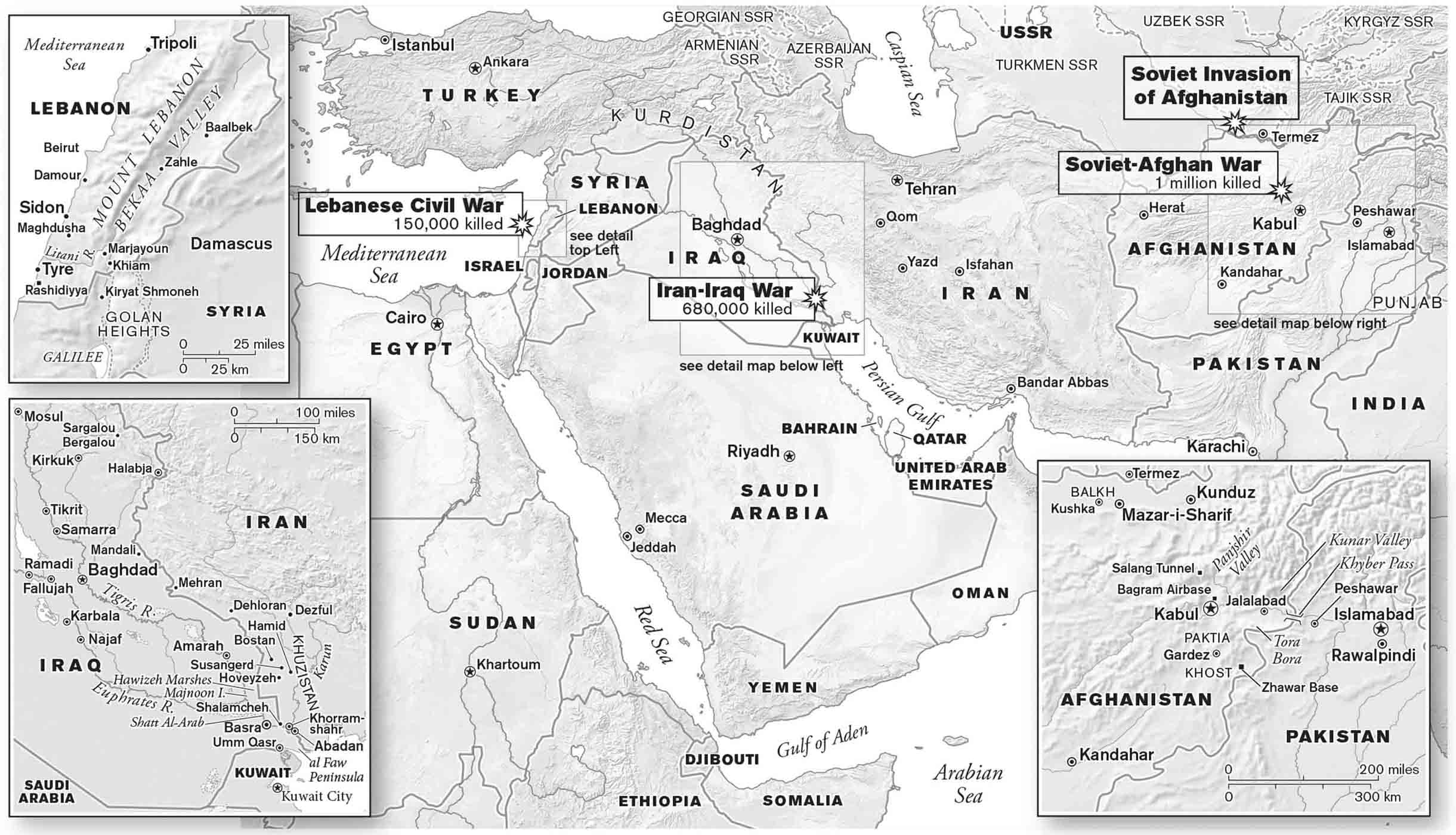

Three vicious conflicts raged through the decade. Where East and Southeast Asia had served as the key theaters of the first and second waves of post-1945 violence, the Middle East emerged as last major battlefield of the Cold War age. The Lebanese Civil War, which began in 1975, served as a harbinger of broader changes. As rival sectarian militias transformed the small republic into a dystopian battlefield, neighboring states and outside powers launched interventions. If Lebanon signaled the rise of a new force in revolutionary politics from the Middle East, the 1979 Iranian Revolution sounded the loudest call. As the world watched, theocratic revolutionaries who seemed more fit for the fifteenth century than the twentieth seized power in one of the region’s largest and most powerful states. This revolution’s shock waves helped set off a vicious war between Iran and Iraq along the ancient frontiers of the Shia and Sunni worlds. But the era’s bloodiest conflict broke out in neighboring Afghanistan, where the Soviet Union staged its largest intervention of the Cold War, in defense of a failing Marxist regime battling Islamic guerrillas. For most of a decade, the Afghan Mujahideen waged a deadly jihad against Soviet troops that helped to bring the Communist giant to its knees. Together, these three conflicts shifted the focus decisively away from the Marxist paradigm of revolutionary violence and toward ethno-religious modes of conflict. This great sectarian revolt signaled the rise of a new revolutionary politics in world affairs that would come to dominate the conflicts of the early twenty-first century.

Leaders in both Washington and Moscow recognized these changes, but they did not fully appreciate their implications. As the CIA warned in 1981, the recent wave of resurgent Islamic nationalism had destabilized the Middle East and now threatened U.S. strategic interests.4 But officials in the White House and the Kremlin remained fixed in their Cold War mind-sets. If ethno-religious fighters destabilized existing regimes, American and Soviet officials worried, their Cold War adversaries were likely to benefit. U.S. national security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski warned in late 1978, “An arc of crisis stretches along the shores of the Indian Ocean, with fragile social and political structures in a region of vital importance to us threatened with fragmentation. The resulting political chaos could well be filled by elements hostile to our values and sympathetic to our adversaries.” But Brzezinski underestimated the power of these new players. “There was this idea that the Islamic forces could be used against the Soviet Union,” State Department officer Henry Precht later explained. “The theory was, there was an arc of crisis, and so an arc of Islam could be mobilized to contain the Soviets. It was a Brzezinski concept.”5 This rationale would drive the Carter administration’s paradoxical decision to establish an aid program for Islamic fighters in Afghanistan at the same time that the White House agonized over the fallout from the Islamic revolution in Iran.

While the sectarian resurgence created problems in Washington, it represented a more immediate threat to the sclerotic Brezhnev regime in Moscow. Soviet leaders worried that the waves of Islamic radicalism sweeping through Iran and Afghanistan might spill over the border to the large Muslim populations living inside the Soviet Union. U.S., Indian, and British officials speculated in mid-1979 that Soviet leaders were justifiably concerned that the Islamic “virus might spread to the Soviet Moslem population.” Resurgent Islamic fundamentalism also threatened the young Marxist regime in Kabul, which began pleading with the Kremlin to intervene in Afghanistan. Though they were loath to see a Communist regime on their own border collapse, Soviet leaders worried about the prospect of staging a military intervention in the fractious nation.6 In the end, Cold War priorities pushed both superpowers to join the fray in ill-conceived attempts to respond to the great sectarian revolt. U.S. leaders denounced Iranian fundamentalists at the same time that they channeled aid and weapons to Afghan jihadists. Soviet leaders, meanwhile, charged into a conflict that bore striking similarities to the American war in Vietnam. By the time the smoke cleared, nearly three million people lay dead and a new mode of revolutionary violence had risen from the Cold War’s ashes.7