Introduction: A Geography of Cold War–Era Violence

This is a history of the deadliest military theater of the Cold War age. It focuses on a nearly contiguous belt of territory running from the Manchurian Plain in the east, south into Indochina’s lush rain forests, and west across the arid plateaus of Central Asia and the Middle East. Seven out of every ten people killed in violent conflicts between 1945 and 1990 died inside this zone. These killing fields skirted the frontiers of the Communist world and, together with Europe’s Iron Curtain, formed the front lines of the Cold War. Here, along Asia’s southern rim, superpower armies, postcolonial states, and aspiring revolutionaries unleashed three catastrophic waves of warfare that killed more than fourteen million people. The superpowers flooded these lands with foreign aid—eighty cents out of every dollar Washington and Moscow sent to the Third World ended up here. Ninety-five percent of Soviet battle deaths occurred inside this stretch of territory. For every thousand American soldiers killed in combat during the period, only one died elsewhere.1

The territory itself has been known by a number of names. It roughly corresponds to the overland trade routes of the ancient Silk Road and the southern borders of the Mongol Empire. In the twentieth century, geographer Nicholas Spykman would name this area the “rimland.” Officials in the Dwight Eisenhower administration spoke of East Asia and the Northern Tier, while Soviet officials would later make plans for the Southern and Eastern Theaters. The term southern Asia is perhaps most accurate, but it, too, risks confusion both because of its similarity to South Asia (the Indian subcontinent) and because the so-called Middle East is often treated as if it were somehow separate from Asia. For the purposes of the Cold War, this stretch of territory served as the killing fields, home to the bloodiest fighting of the post-1945 era.

Despite serving as the era’s central axis of warfare, these Cold War bloodlands are not mentioned in conventional histories as a defined space—the area has not been mapped, and many of its constituent conflicts are little more than footnotes in the story of post-1945 international relations. As a result, the global picture of Cold War–era violence remains shapeless and is all too often overlooked outside scholarly circles.2 Instead, most of us tend to see the period from the perspective of the industrialized world: as a time of relative peace. Indeed, the most influential historian of the Cold War, John Lewis Gaddis, would call the Cold War a “long peace,” an apt reference to the near absence of Great Power warfare during the era. For Gaddis, Third World conflicts shifted the superpower competition to the level of proxies, helping to ensure that the Cold War remained mostly cold and providing a measure of stability to the larger international order. Yet, for millions of people throughout the postcolonial world, the post-1945 era was marked by brutal warfare. What would a broad history of the Cold War age look like, I wondered, if told from the perspective of the period’s most violent spaces?3

This book seeks to tell this story. It follows the course of the era’s deadliest conflicts and examines how this violence shaped the Cold War and the decades that followed. The most concentrated violence of the age did not occur when or where I had expected. The killing focused on certain places and certain times, and it followed identifiable patterns. As the process of decolonization ran headlong into superpower struggles for regional dominance, the era’s bloodiest battlefields traversed the southern rim of Asia. Across these Cold War bloodlands, postcolonial revolutionaries struggled to make a new world while Great Power armies launched brutal campaigns aimed at holding the line. It is a side of the Cold War age about which we know surprisingly little: a long chain of vicious conflicts fought across southern Asia to mark the transition from a world of colonies to a world of nation-states, to lay down the far frontiers of the Cold War order, and to reshape international politics.

Far from being incidental to the superpower struggle, violence played a fundamental role in shaping the contours of the U.S.-Soviet rivalry and international politics after 1945. If Latin America was Washington’s imperial workshop and Eastern Europe was Moscow’s laboratory of socialism, the contested borderlands of southern Asia served as the staging grounds for both superpowers’ containment strategies and for new modes of revolution and resistance.4 As decolonization destroyed a centuries-old European colonial order, Washington and Moscow rushed to fill the vacuum. Both superpowers sent their armies to battle guerrilla fighters on the far frontier; both scoured the globe in search of allies that might serve as proxies in the struggle to contain their adversary. Rarely did these conflicts carry geopolitical significance commensurate with the resources that Washington and Moscow devoted to them. But Cold War strategies (Washington’s bid to contain Soviet influence and Moscow’s parallel campaign to breach a feared capitalist encirclement) magnified the importance of these conflicts and led both superpowers into interventions that frequently ran counter to their long-term interests.5

While the drive to contain their rival’s influence dragged Washington and Moscow into the postcolonial world, Third World revolutionaries and political leaders fought to realize their own visions of decolonization and liberation. Local forces joined the struggle along the Cold War frontiers in complex patterns of collaboration, co-optation, and resistance in bids to assert their own influence while manipulating superpower anxieties to win vital assistance for their local struggles. As they did so, regional players disrupted superpower designs and redirected the currents of international power. These postcolonial battlefields emerged as new political spaces in which superpowers, local governments, and revolutionaries refined techniques of mass violence, rewrote the politics of revolution, and reshaped the structures of world power. In the process, the battles for the Cold War borderlands forged many of the greatest geopolitical transformations of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries—these lands witnessed the consolidation of a new system of postcolonial states, the rise and fall of Third World communism, and the emergence of a new politics of sectarian revolution.6

My purpose is not to argue that the conflicts covered in this book are best understood as proxy battles of the Cold War; nor is it to suggest that the Cold War was in fact the sum total of wars in the Third World. The book does not claim to offer a full or encyclopedic account of Third World conflicts during the post-1945 era. Rather, it tells the history of the most intensely violent theater of the superpower struggle: the Cold War’s postcolonial borderlands along Asia’s southern tier. In doing so, it examines the bloodiest encounters of the era and considers how they shaped the course of world affairs in the second half of the twentieth century. It argues that the Cold War forged a network of connections that linked these struggles together and increased their destructive potential by an order of magnitude. Although each individual conflict may not have been a direct outgrowth of the Cold War, each was shaped in important ways by the larger structure of superpower relations during the period. While a case may be made for treating the superpower conflict separately from these conflicts along the periphery, such an approach obscures the rivalry’s global impact and overlooks the influence of non-Western societies on the dynamics of the East-West struggle. Conversely, local studies that downplay the Cold War tend to gloss over global influences and place their subjects in a sort of regional vacuum. Instead, this book approaches the Cold War as a worldwide phenomenon—a complex, interconnected web of regional systems stretching around the world and connected to the global latticework of U.S. and Soviet power.

Although parts of this story will sound familiar to many readers, our understanding of it remains surprisingly limited. Conventional wisdom tells us that the Third World experienced violence during the Cold War, but the precise shape of that violence remains indistinct. We remember a few large wars such as Vietnam, Korea, and Afghanistan, but these accounted for less than half the era’s war deaths. Beyond these better-known conflicts, we have a tendency fall back on generalizations—wars took place in the Third World or in Asia, Latin America, or Africa—but these are enormous regions, and only a fraction of the countries in the developing world suffered such massive bloodletting. These vague characterizations are insufficient for understanding such weighty issues.

Our understanding of post-1945 warfare remains strangely shapeless; it contains virtually no sense of scale, timing, or geography. And this lack of structure is troubling. Consider, for example, histories of World War II in Europe that gloss over the fact that the overwhelming majority of the casualties took place on the Eastern Front—that ignore Stalingrad to focus on Normandy. Such works obscure the enormous role that the Soviet Union played in the war and lionize American contributions. Likewise, how seriously can we take a study of the Vietnam War that downplays the fact that far more Vietnamese were killed than Americans? Such a history would mask the incredibly brutal impact of the war on the civilian population of Vietnam. Why should we not apply the same logic to the Cold War era? By ignoring the spatial and temporal dimensions of post-1945 warfare, or approaching them in a piecemeal fashion, we conceal core dynamics of power and violence in the Cold War international system. Put simply, by avoiding a systematic examination of the period’s wars and massacres, we whitewash the inherently violent history of the post-1945 era.

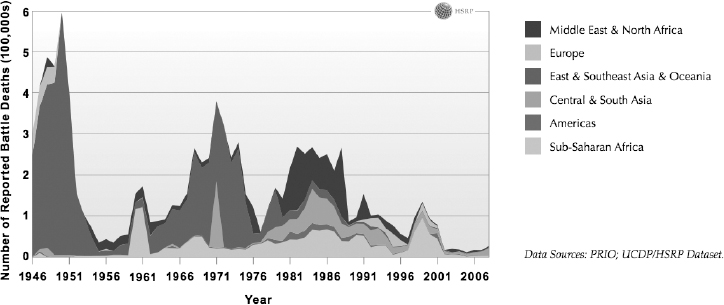

I therefore chose to let the numbers be my guide. Mortality figures, imprecise as they may be,7 provide the most straightforward means of gauging the scale and intensity of mass violence across disparate societies; they allow us to establish a rough map of mass killing across both time and space. When we do so, a startling picture of Cold War–era violence emerges.

The post-1945 era’s conflicts were neither random nor evenly distributed across the developing world. Although historians tend to treat Third World clashes indiscriminately, Africa, Latin America, Asia, and the Middle East suffered dramatically different levels of violence over different periods. As a result, the incidence of Third World conflicts during the Cold War followed discernible geographic and historical logic. Indeed, more than 70 percent of the people killed during the Cold War died along the eastern, southern, and western periphery of the Asian landmass. Superpower interventions tell a similar story. Soviet forces lost 722 soldiers in their 1956 invasion of Hungary and 96 in the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia; nearly 15,000 died in the Soviet-Afghan War. Washington’s invasions of the Dominican Republic, Grenada, and Panama resulted in 80 to 90 U.S. deaths; about three times that number died in the 1983 intervention in Lebanon alone; and around 95,000 U.S. troops were killed in Korea and Vietnam. All told, Soviet and U.S. military forces suffered 95 percent and 99.9 percent of their combat deaths, respectively, inside these Cold War bloodlands.

The Three Waves of Cold War–Era Violence

(Courtesy of Andrew Mack, director, Human Security Report Project, Simon Fraser University)

Likewise, the flow of foreign aid to the Third World reveals the importance the superpowers placed on the Asian rim. According to the United States Agency for International Development, between 1946 and 1992 the U.S. government allocated over $106.5 billion in loans and grants to Middle Eastern countries. During the same period, Washington sent just under $20.2 billion to sub-Saharan Africa, and $32.6 billion to Latin America. Asia received just over $100 billion. Washington sent five times as much aid to the Middle East during the Cold War as it did to sub-Saharan Africa and over three times as much as it sent to Latin America. In other words, about 79 cents out of every dollar the U.S. government sent to the non-Western world during the Cold War went to either the Middle East or Asia.8 Soviet aid figures are somewhat more difficult to obtain, but the CIA estimated that between 1955 and 1965, Moscow sent just over $2 billion in economic aid to the Middle East, $729 million to Africa, $115 million to Latin America, and $2.1 billion to Asia. If correct, this means that, for every dollar the Soviets spent in Africa, they spent three in Asia; for each dollar they sent to Latin America, they spent $17 in the Middle East. As such, around 82 cents out of every dollar Moscow sent to the developing world during the period ended up in either the Middle East or Asia.9

It was no coincidence that the fiercest battles of the Cold War era raged along the borders of what would become the world’s two great Communist powers. These Cold War borderlands constituted the most hotly contested terrain of the superpower struggle. It was here along the postcolonial frontiers of their respective spheres of influence that the superpowers felt most vulnerable: unlike Latin America, Europe, and Africa, each of the regions along the Cold War borderlands would swing between strategic alignment with Washington and Moscow. It would be here that the United States deployed its containment strategies against the expansion of Communist power, sending its forces to distant stations overseas along the front lines of the Communist world. And it was here that the Soviet Union and its allies sought to breach a perceived capitalist encirclement. By projecting their power and influence into these postcolonial societies, Washington and Moscow followed in the footsteps of their imperial predecessors. Even as World War II and the global process of decolonization destroyed the old imperial order, it set the stage for a new Great Power struggle that would unleash new waves of violence across the postcolonial world.