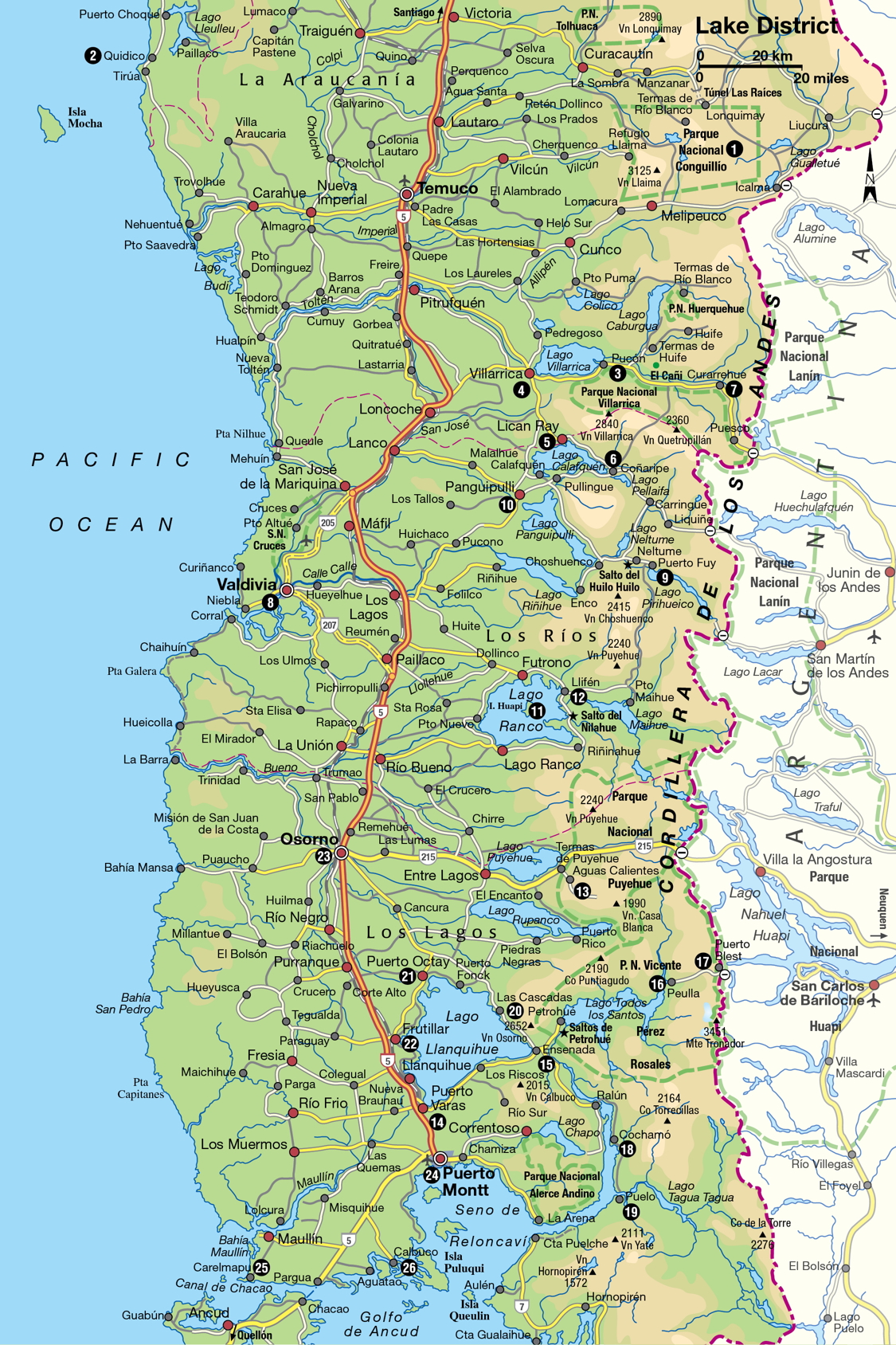

The Lake District

Snow-capped mountains reflected in looking-glass lakes, quaint wooden hamlets steeped in healthy mountain air, fishing ports, and old rural traditions – the Lake District is Chile’s wonderland.

Main Attractions

The Lake District exercises a near-mythic fascination on Chileans. The south symbolizes everything healthy, unspoiled, and pure in Chile and its people. City folks, particularly in Santiago, look kindly on southerners as their own better selves and foreign visitors will be made to feel very much at home in the Lake District, where European influences of all kinds, including immigration, have long been welcomed. An early pioneer and champion of southern settlement and development, Vicente Pérez Rosales, exemplified this Eurocentrism when he announced in 1854 that “the word ‘foreigner’ has been eliminated in Chile. It is an immoral word and should disappear from the dictionary.” Pérez Rosales was not thinking of Peruvians or Brazilians or other mestizo nations – he meant the Germans, Austrians, Swiss, and Italians whose communities are still common in the south.

Unfriendly encounters

However, native Mapuche roots are still not far from the surface of southern Chile’s collective memory. The south, where most of the country’s rural indigenous population lives, was not fully dominated by the European-descended settlers until the second half of the 19th century. For example, the first European colony was established at what is now the lakeside resort center of Villarrica, and was besieged by Mapuches in a 1598 uprising, collapsing without survivors in 1602. It was not re-established until a military mission arrived in 1882, nearly three centuries later.

Lakeside view.

Abraham Nowitz

In the interim, an uneasy state of semi-war prevailed. Early in the 1600s, the River Biobío (which reaches the sea at what is now the port of Concepción) was established as the frontier between the Spanish colony and native lands, but the truce was violated annually in raids from one side or the other. Spanish mercenaries fought to capture Mapuches and sell them into slavery, while the Mapuches raided to plunder cattle and other goods or to punish the invaders. Regular peace conferences between the two sides usually ended in great celebrations of feasting and drinking and vows of friendship – which would invariably last only a few months before the next outbreak of hostilities.

Finally, commerce pacified the situation. A regular trade in cattle, woven goods, knives, arms, and liquor developed, although violent outbursts between Mapuches and European soldiers, brigands, and shady dealers of all sorts continued to occur regularly. Naturally, the mestizo population grew steadily with the constant contact, and colonial garrison commanders preferred them as soldiers since they knew the area well and were notoriously impervious to hardship.

Church in Puerto Octay.

Abraham Nowitz

These hostilities meant that the Lake District was, until relatively recently, unexplored territory for those of European descent. Lago Colico, near Pucón, was the last of the big lakes to be discovered by Europeans, making its first appearance on maps in the early years of the 20th century. The great Lago Llanquihue near Puerto Montt was first sighted by Pedro de Valdivia in 1552, but Mapuche raids put it effectively out of bounds to Europeans until new waves of settlers began to arrive three centuries later.

Farmstead overlooked by Volcán Osorno.

@Apa/Abe Nowitz

Life in the outback

Chile’s south is a more recently tamed version of the North American Wild West, and, in more remote areas, life revolves around horses, farm work, and social events, lubricated with large quantities of wine or chicha made from fermented apples. Country families tend to live off seasonal sales of milk, or a cash crop, or tourists, spending long months consuming the stores of grain they harvested themselves, while the men look for paying jobs in the larger towns and cities.

FACT

The copihue, Chile’s national flower, grows in forests from Valparaíso to as far south as Osorno. A climbing evergreen, its bell-shape flowers – beloved by humming birds – are usually red, although there is also a white variety.

The rural areas are connected by an extensive network of local buses, which transport schoolchildren, farmers and country residents returning from the larger towns with provisions. The buses are slow due to the terrain and the constant stops at every lane or farmhouse, but they are very cheap and reach many remote settlements. The first and sometimes only bus tends to leave before dawn, so it is always prudent to inquire about schedules the day before traveling. As the terrain is ideal for backpacking and hiking, Chilean youth swarm southward in the summertime, many of them spending long hours on the highway awaiting motorists or truckers who will give them a lift. Most have the barest minimum of funds and camp wherever possible.

Gateway to the Lake District

The Lake District is generally considered to begin at the Toltén River, which flows off Lago Villarrica, but this is more a result of the area’s fame as a resort region than strict topographic considerations. The characteristic combination of volcanoes and lakes actually begins farther north, around the area of Parque Nacional Conguillío, northeast of Temuco, which is located 677km (421 miles) south of Santiago. This region is home to several volcanoes, including Lonquimay (2,890 meters/9,480ft), which entered into full eruption in 1988 and blanketed the area with dangerous volcanic dust; and Llaima (3,125 meters/10,249ft), which erupted in 1994. Lonquimay means “without a head” in the Mapuche tongue, referring to the volcano’s flat top.

This is also Mapuche territory – the Mapuches’ ancestors used the accessible mountain passes and gathered pine nuts from the ancient araucaria, or monkey puzzle tree, which is endemic to the southern Andes. There are male and female araucaria trees – biologists can determine their sex by examining their bark. These rare coniferous trees, which take 500 years to mature fully and can live for more than 1,000 years, were endangered by logging activities until President Aylwin’s government responded to environmental campaigners and prohibited their destruction in March 1990.

Temuco

Temuco, founded in 1881, following an important treaty between the new republic and the Mapuches, is now a rapidly growing industrial town, and a good base from which to explore the northern Lake District. Its Museo Regional de la Araucanía (Tue–Fri 10am–5.30pm, Sat 11am–5pm, Sun 11am–2pm; charge) provides information on the native people and their history. The Museo Nacional Ferroviario Pablo Neruda (Oct–Mar Tue–Fri 9am–6pm, Sat and Sun 10am–6pm; Apr–Sept Tues–Fri 9am–6pm, Sat 10am–6pm, Sun 11am–5pm; charge), named after Chile’s Nobel poet who spent his childhood in Temuco and whose father was a rail worker, attractively sets out the history of the railway in Chile.

Mapuches from the surrounding countryside come to Temuco to sell their wares; the central market, although rather touristy, is a good place to buy local handicrafts and to try traditional dishes. The Cerro Ñielol hill and forest park, where the national copihue flower grows in abundance, offers the best view of the city.

From Temuco, it is worth making a trip to Cholchol, 29 km (18 miles) northwest of the city, a typical Mapuche village where you can see rucas, the Mapuches’ traditional thatched dwellings.

Lago Gualletué – source of the Biobío

The town of Lonquimay and the land surrounding it lie to the east of the Andean cordillera, despite the general rule that the highest peaks mark the territorial boundaries between Chile and Argentina. However, Lago Gualletué southeast of Lonquimay provides the headwaters of the important Biobío River, which then runs north for nearly 100km (60 miles) before turning westward toward the Pacific Ocean at Concepción. As this river was long considered the border dividing Spanish lands from unconquered Mapuche territory, Chile claimed the hydrographic basin.

The main road to Lonquimay passes through the Túnel Las Raíces. This was originally a railway tunnel, built in the 1930s as part of a plan (subsequently abandoned) to connect the Atlantic and Pacific oceans by rail. The tunnel is passable in all weathers (though large icicles form in winter).

On the road to the tunnel from Curacautín there are several thermal baths, as well as the beautiful 50-meter (16ft) Princess Waterfall and two huge volcanic rocks, Piedra Cortada and Piedra Santa, which were considered sacred by the indigenous population.

Parque Nacional Conguillío

Parque Nacional Conguillío 1 [map] can be reached from Curacautín in the north or Melipeuco in the south. Both routes skirt the snow-covered Volcán Llaima, and lead through virgin forests of araucaria and other Chilean species such as coigüe and raulí, as well as oak and cypress. Twelve hundred year-old araucaria trees can be seen in Parque Nacional Conguillío, which was set up in 1950. Conguillío’s prehistoric feel led the BBC to film parts of its 1999 natural history series Walking with Dinosaurs here.

FACT

Chile’s native parrots abound in the mountains around Conguillío and give campers a raucous early morning call.

Three tiny lakes in the park (Verde, Captrén, and Arco Iris) were formed by lava flows that blocked several rivers. The lakes are just a few decades old, and the trees that once grew on their beds can still be seen below the water. Volcán Llaima now has a small, modern ski resort on its slopes, at Los Paraguas.

A private concessionaire manages the main campground on the shores of the largest lake, Lago Conguillío, as well as several log cabins in a stunning location in an araucaria forest. December is the best time to visit, before the Chilean summer vacation crowds arrive in January and February.

To the north of Curacautín is another national park, Parque Nacional Tolhuaca, with camping facilities on the shores of the lovely Laguna Malleco. A few kilometers before the park entrance, there are some hot springs, the Termas de Tolhuaca, with a small hotel.

FACT

Some Mapuche families living near Tirúa scratch a living by harvesting and selling the edible cochayuyo seaweed that amasses along the seashore.

On the coast, west of Conguillío, is Lago Lleulleu (in the Mapuche language, a repeated word has extra importance). Aside from the tiny community at Puerto Choque, the only civilization nearby is at Quidico 2 [map] on the ocean, which is popular in the summer for its excellent seafood and windswept beach. The end of the main road is just past Tirúa where Mapuche chiefs once charged a toll for land traffic between Concepción and Valdivia. According to legend, the bishop of Concepción was kidnapped and held here in 1778, only escaping when a rival chief won his freedom in a game of chance.

Lago Villarrica.

Bigstockphoto

Pucón

Next to the beaches at Viña del Mar and Reñaca, the area around Villarrica and Pucón is the most popular holiday resort in Chile. The two towns are the main urban centers on the end of Lago Villarrica, which is dominated by the active Volcán Villarrica (2,840 meters/9,320ft), just an hour’s detour from the north–south Pan-American Highway. Pucón 3 [map] could be called the “Viña of the South” for its success in attracting summer tourists. It is enormously popular among the Chilean middle classes, who are rapidly buying up the summer condominiums along the beach. Many flock to the area in the summer months, sunbathe on the beach, take part in noisy water sports on Lago Villarrica by day, and crowd the casino in the Gran Hotel Pucón by night.

Though it has become very commercial, Pucón provides all the services a tourist could want, including an excellent variety of restaurants, bars, and discotheques, and is extremely popular with backpackers.

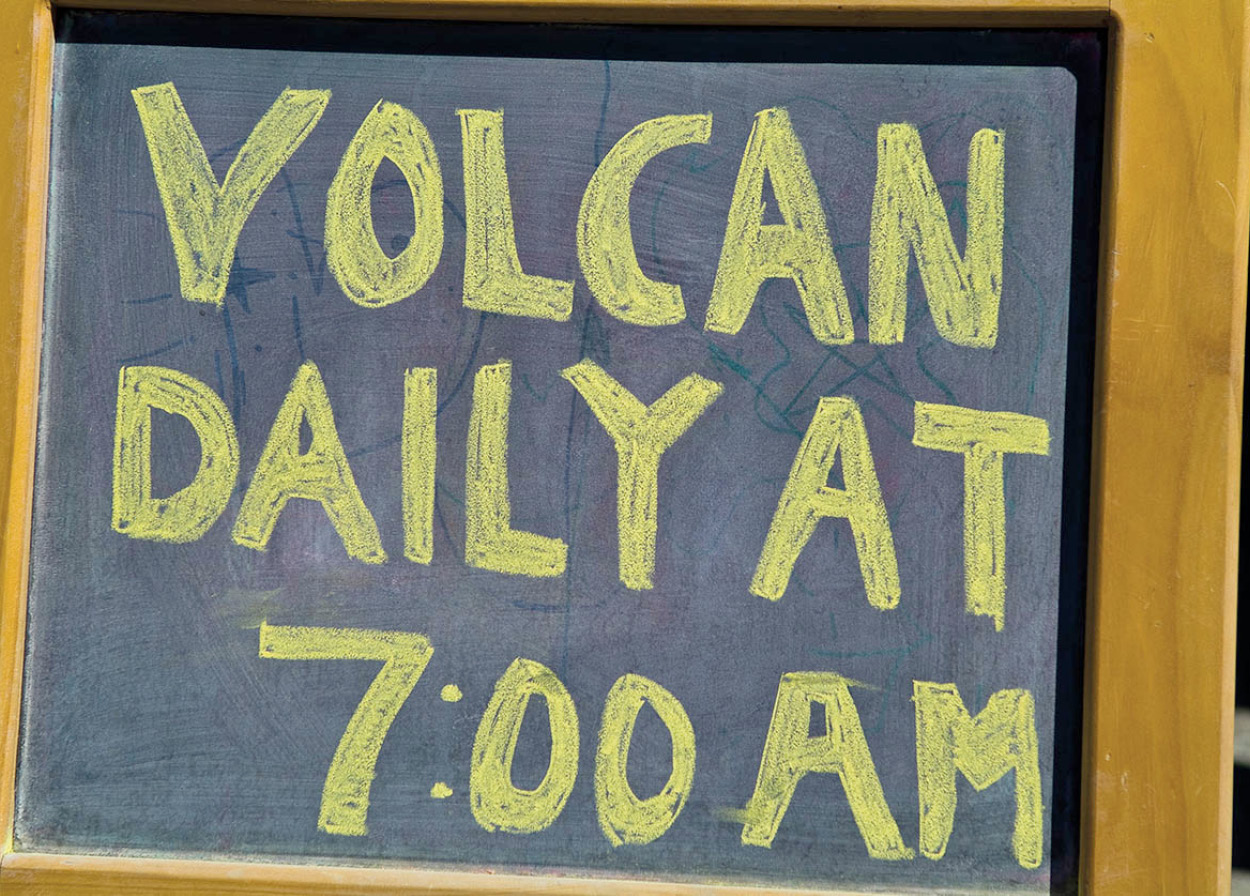

The town is also a key center for adventure tourists, and by far the most popular activity is the one-day hike to the lava-filled crater of Volcán Villarrica. An increasing variety of water sports, including rafting and kayaking are also practiced on the Trancura River. Though the service offered by adventure travel agencies varies, most provide high-quality imported equipment and qualified guides trained to ensure international safety standards.

Skiing is available in winter on the slopes of Volcán Villarrica. More relaxing activities include horseback riding, fishing, and visits to nearby hot springs and national parks.

The area around Pucón has also pioneered environmental tourism projects. El Cañi, east of Pucón, is one of Chile’s first private parks. Its ancient araucaria forest growing on an extinct volcano became a reserve in 1992 with funding from Ancient Forests International and has been developed as a center for environmental education and scientific research. Though it requires a steep three-hour hike, reaching the summit rewards the climber with spectacular views of all the area’s volcanoes on a clear day. Visits are best organized through the École hostel in Pucón.

Backpacker hangout, Pucón.

© 2009 Richard Nowitz

Villarrica

Numerous Mapuche communities are tucked away in the hills surrounding Villarrica 4 [map], and each summer a Mapuche cultural festival is held in the town. This includes a nightly demonstration of religious rituals. Some unusual craft work can be found among the stands, but most of the work has long been copied by artisans in Santiago and elsewhere.

One of the town’s main streets is named after General Emil Koerner, the German military scientist who was hired in the late 19th century by President Balmaceda to reorganize the Chilean armed forces (he used the area for training). Koerner then betrayed Balmaceda to side with an 1891 insurrection fomented by local oligarchs. The oligarchs won, President Balmaceda committed suicide, and Koerner proceeded to reshape the army along Prussian lines, a model that remains largely in force today. His prestige led to a surge of pro-German sentiment, which helped to stimulate a second wave of German immigrants, most of whom headed for the newly available lands in the south.

Parque Nacional Huerquehue

Just a short drive from Pucón to the north and northeast are lakes Caburgua and Colico, and, in the mountains of Parque Nacional Huerquehue, lakes Tinquilco, Toro, and Verde. Rare outcroppings of “flywing” rock crystal usually observed only in the coastal mountain range 100km (60 miles) to the west give some of Lago Caburgua’s beaches white sand rather than the usual black sand that comes from the volcanic rock elsewhere in Chile’s Lake District. The lake is surrounded by densely forested hills, some areas of which can be explored on defined paths. Its waters flow underground, producing the springs at Ojos de Caburgua, a popular picnic spot. Access to the Huerquehue Park lakes is a serious 5km (3-mile) climb but a small bus company, Buses Caburgua, operates a minibus service that leaves Pucón approximately every 30 minutes and takes visitors right to the park entrance.

Puma live farther up in the mountains; these animals are rarely seen, but come closer to human civilization in winter when food is scarce. Pumas do not generally attack humans unless threatened, but still need to be considered dangerous animals. An 80km (50-mile) route from Caburgua’s north shore through the Blanco River Valley can be hiked in about four days, ending up in the outpost of Reigolil (where a bus descends to Curarrehue four times a day). A traverse from Volcán Quetrupillán to the village of Puesco through araucaria forests has increasingly replaced the circuit around Volcán Villarrica as the most popular hiking route in Parque Nacional Villarrica. Local tour agencies leave hikers at the beginning of the trek, and there are public bus services back to Pucón.

South of Villarrica, a half-hour’s trip on a paved highway leads to the rapidly expanding resort of Lican Ray 5 [map] on Lago Calafquén. Wood furniture-making is an important economic activity in this area, and there are dozens of workshops, particularly on the road from Villarrica to Lican Ray. Farther along the lake is Coñaripe 6 [map], which retains the atmosphere of pre-boom Lican Ray. Regular buses do go this far, but Coñaripe is the end of the line before the rugged unpaved circuit around the lake, and the “back way” into Panguipulli.

Thermal baths proliferate across the area due to the constant activity in the volcanic belt that runs along the cordillera. Some, such as the Termas de Menetué or Termas de Huife farther east of Pucón are upscale commercial operations with eating and lodging facilities and bathing fixtures. Others, including the tiny Termas de Ancamil, just before Curarrehue, 45km (28 miles) east of Pucón, are rustic, family-run affairs where one simply descends into the cave with a candle and bathes, while the Termas Geométricas, some 16km (10 miles) east of Coñaripe, have architecturally interesting wooden walkways joining the different pools.

Local farmer, Pucón.

Nicholas DeVore/Getty Images

Frontier Traditions

Rural traditions persist in many frontier towns of southern Chile. Men can often be seen wearing flat-brimmed felt hats, and they are quick to invite visitors to drink a sweet wine that goes down with treacherous ease. On special occasions, a host family will kill a sheep or goat by plunging a knife into the neck and catching the blood in a pan filled with cilantro (coriander), where it is congealed with lemon juice to produce ñache, which is considered a great delicacy and pre-feast appetizer.

Grains are the traditional farm commodity, though the uncertainty of the weather makes farming risky. Potatoes are easily grown, but transport costs wipe out any chance of profit, so farmers usually consume them or use them as animal feed. Hops and sugar beet are also grown. Pasture is abundant, and many families earn a few pesos selling milk to the big dairy plants.

To fortify themselves for heavy farm work, the men breakfast on chupilca, white wine poured over toasted wheat, or mudai, a mushy, carbohydrate-rich juice made from cooked grains. Visitors should avoid giving offense by always accepting anything offered, even if they cannot bring themselves to sample it. When you’ve had enough, just leave the plate or glass untouched before you.

Curarrehue

The town of Curarrehue 7 [map] is a typical southern frontier center, where families often have relatives on the Argentine side and travel across the border to take advantage of work opportunities. The Chile–Argentina border in the south is lightly guarded, as the mountain passes are essentially uncontrollable. During the Pinochet dictatorship, many of these frontier towns smuggled people in and out who either could not move around legally or were in serious trouble for political reasons. Cattle-smuggling into Chile from Argentina causes occasional outbreaks of foot-and-mouth disease, which cannot be controlled in Argentina’s vast ranches but has been basically eradicated in Chile.

Kunstmann brewery, Valdivia.

© 2009 Richard Nowitz

Valdivia

Valdivia 8 [map] is the best example of the urban face of Chile’s south: sophisticated and festive, rainy and verdant, with a palpable German influence in architecture, cuisine, and culture. Although usually treated as part of the Lake District, Valdivia is located at the crossroads of two rivers and is just a few kilometers from the sea, separated from the lakes by the coastal mountain range. The approaches to the city are marshy breeding grounds for unusual waterfowl. Named for the first conquistador to enter Chile from Peru, Pedro de Valdivia, the city was founded in the mid-1500s but had a difficult time of it for the first 100 years. It was taken over by a Dutch pirate in 1600 and, being on the Mapuche side of the Biobío River dividing line between Crown and Mapuche territory, had to await the building of fortifications in the mid-1600s to achieve a measure of security. The Museo Histórico y Antropológico Mauricio van de Maele (Jan–Feb daily 10am–8pm, Mar–Dec Tue–Sun 10am–1pm, 3–6pm; charge), on Teja Island in the middle of Valdivia, is housed in an old settler’s mansion and includes Mapuche artifacts and period furnishings – providing an excellent insight into the prosperous lifestyles of the 19th-century German immigrants.

In 1960, Valdivia was the epicenter of the world’s largest recorded earthquake, followed by a tidal wave whose effects can still be seen. Most of the old buildings were destroyed, but some European-style buildings remain by the waterfront. The Museo de Arte Contemporáneo (Jan–Feb daily 10am–2pm and 4–8pm, Mar–Dec Tue–Sun 10am–1pm and 2–6pm; charge), also on Teja Island, is built on the ruins of the old Andwandter brewery. It has no permanent collection but holds exhibitions of contemporary Chilean artists.

Valdivia has a popular week-long summer festival in February in which musical shows are staged on bandstands along the river bank, boats parade down the river, and firework shows are presented on the last afternoon and night. There is also a film festival.

The city’s long riverside walks are full of visitors throughout the season, as are the nearby beaches. The Parque Saval on Isla Teja has a riverside beach, and the nearby Botanical Garden, with many native species, is worth a visit.

A highly recommended stop is the Feria Fluvial, a lively fish market on the quay from which all the river cruises depart. Fat sea lions come right up into the market, but be careful: they have been known to attack passers-by.

Fresh fish at the Feria Fluvial in Valdivia.

Bigstockphoto

Corral and Niebla

Though swimming is possible in the rivers, most bathers head for the port villages of Corral and Niebla. Colonial-era fortresses are preserved at the latter site, which independence hero Lord Thomas Cochrane, a dashing Scots navy commander in the service of the Chilean rebels, took from the Spanish against heavy odds in 1820. For a bit of exercise, visitors can row from Corral to the tiny island of Mancera, Valdivia’s military headquarters during the 18th century, to see its small church and convent.

FACT

Valdivia is home to one of Chile’s oldest and largest independent breweries, the Cervecería Kunstmann. Its beer garden and restaurant on the road to Niebla is a favorite tourist attraction, although rather pricey.

River trips from Valdivia north to the Santuario de la Naturaleza Río Cruces pass through the habitat of black-necked swans to the confluence of three rivers. A few years ago, this sanctuary was the subject of a major environmental controversy when, following the start of operations at a nearby wood-pulp plant, the swans, a relatively rare South American species, started to die and many more migrated. Effluent from the plant was blamed for the disappearance of the waterweed on which the swans feed. The company was forced to reduce the plant’s output, prior to building a duct out to sea, and the swan population now appears to be recovering slowly. Many boats make a stop at the indigenous Huilliche village of Punucapa.

Sign advertising a volcano hike.

@Apa/Abe Nowitz

Seven Lakes detour

The largely underdeveloped Seven Lakes district is among the least visited by vacationers due to a peculiar topographical layout and poor access. The district is named after seven lakes that all share the same river basin and include the large lakes Calafquén, Panguipulli, and Riñihue, the smaller lakes Pellaifa, Neltume, and Pirihueico, and Lago Lacar in Argentina. The lakes are generally bordered by heavily wooded cliffs with steep descents; roads are potholed and slippery at the best of times, with difficult climbs and narrow turns through the mountains, which are often impassable in winter. Low-suspension vehicles will fare worst. However, the landscapes are spectacular, and local residents will guide visitors to even more extraordinary spots. These lakes are good for fishing and exploring, but not so good for bathing as beaches are few and far between.

The circuit around Lago Calafquén is dominated by the seemingly changing position of Volcán Villarrica to the north. Finally, Volcán Choshuenco (2,415 meters/7,923ft) appears to the south. Recent lava flows can be observed from the highway shortly after leaving Lican Ray. From Coñaripe an alternative route leads to the small Lago Pellaifa after a ferocious climb at Los Añiques. The way down leads through an agricultural valley to the Mapuche village of Liquiñe.

From there, it is possible to drive to Lago Neltume and Puerto Fuy 9 [map] on the finger-shaped Lago Pirihueico, which can be crossed in two hours on a ferry boat that connects to an international road to San Martín de los Andes in Argentina.

TIP

Part of the road from Villarrica to San Martín de los Andes in Argentina, a distance of 205km (127 miles), is in poor shape but the views are incomparable.

Panguipulli ) [map] (Town of Roses) was formerly the railway station that received logs dispatched from the interior via steamboats plying the lake of the same name. The construction of roads later superseded the lake transport system. The town is brilliantly decorated with rose bushes. As Panguipulli is located on the flat central plain rather than in the mountains, it tends to be hotter than other lake towns, and its beaches are somewhat less impressive.

On clear days, you should be able to make out Volcán Choshuenco, situated some 50km (30 miles) to the southeast. The volcano itself can be climbed by motor vehicle up to the refuge after a trying, 80km (50-mile) drive along the lake. To the east, about halfway to Puerto Fuy, is the Salto del Huilo Huilo, the highest and one of the most impressive waterfalls in Chile, which crashes down a deep vine-covered gorge into the River Fuy. Nearby is the entrance to the Huilo Huilo Reserve, a private park with spectacular scenery and two luxury hotels. Note that it is impossible to continue the circuit around Lago Riñihue out of season (and frequently in season as well) due to a severe, 7km (4-mile) climb with terrible road conditions just after the tiny lakefront community of Enco. An approach can be made from the town of Los Lagos on the Pan-American Highway, passing through the town of Riñihue.

Lakeside view at dusk.

© yoel harel / Alamy

Lago Ranco

The enormous Lago Ranco ! [map] and the smaller adjacent Lago Maihue have developed considerably as tourist centers in recent years. However, out of season they are very quiet. On the northern shore of Lago Ranco, the resort of Futrono is accessible by turning off the Pan-American Highway at Reumén. For foot travelers, buses to Futrono leave regularly from Valdivia and Río Bueno all year round. Guided adventure tourism in the surrounding hills is still little developed, though Futrono has a network of rural tourism.

Many of the communities surrounding the lake originated as fishermen’s hostels; a couple are now successful lodges serving upscale clients. The town of Lago Ranco itself is full of cheap tourist guesthouses. The pebble beach and a hill behind the town give fine panoramic views. Boats can be rented when available.

FACT

The Santuario de la Naturaleza Río Cruces, just north of Valdivia, is home to an astounding variety of river birds and plant life. The area was submerged under water in the earthquake of 1960.

The most beautiful and heavily settled part of the lake lies directly east along an unpaved road to the Riñinahue peninsula and the Calcurrupe River near Llifén @ [map], where the paving starts again. The road from Lago Ranco to Llifén is dotted with colonies of new summer vacation homes and crosses Salto del Nilahue, a double waterfall with a tremendous, roaring flow, especially in early summer. From the bridge over the River Nilahue, a tertiary road leads to the lower end of Lago Maihue and the hamlet of Carrán, named for the Carrán volcano which just appeared in 1957 and last erupted in 1979.

The 810-hectare (2,000-acre) Isla Huapi in the middle of Lago Ranco is an indigenous colony with some 40 Mapuche and Huilliche families. Huilliches were the original inhabitants, but Mapuches from Argentina colonized the island. There are ferry services to the island from Frutono and Lago Ranco.

Lago Ranco can be completely circled crossing the new bridge over the Calcurrupe River, which replaced the old vehicle raft. A sturdy high-clearance vehicle is recommended for the unpaved stretches. The Caunahue River Canyon just north of Llifén has a dramatic view.

Parque Nacional Puyehue.

@Apa/Abe Nowitz

Lago Puyehue

Lago Puyehue is known to many travelers since it lies along the main route to Argentina from southern Chile. In wintertime, when heavy snow covers the Andes mountains, bus and lorry traffic from Santiago sometimes has to detour nearly 1,000km (600 miles) south to this pass, which is much lower and usually remains open throughout the year. The road has excellent views of the lake from gently rolling hills, then climbs to 1,300 meters (4,300ft) through Parque Nacional Puyehue on the way to the famous resort of San Carlos de Bariloche on the Argentine side. The main town on the Chilean side is Entre Lagos (Between the Lakes) on the western tip of Lago Puyehue, a former railroad center now heavily dependent on tourism.

FACT

The Termas Puyehue Hotel, situated within Parque Nacional Puyehue, is one of Chile’s most traditional spa resorts, offering both thermal and mud baths. See www.puyehue.cl for more information.

A detour toward Volcán Casa Blanca (1,990 meters/6,529ft) leads to the open-air hot springs at Aguas Calientes £ [map]. The park headquarters here make a good starting point for excursions. The road leads past several small lakes, through lush virgin forest, including an unusual temperate rainforest, and ends at a ski resort on the slopes of the volcano, which can be climbed more easily than Volcán Villarrica farther north. Another topographic oddity is the existence of deciduous trees (beech) at the volcano’s tree line. At the top the views are very impressive even for this region, as the volcanoes Osorno, Puntiagudo, and Puyehue can all be seen in a semicircle.

Farmland near Parque Nacional Puyehue.

@Apa/Abe Nowitz

The area around nearby Lago Rupanco tends to be exclusive and upscale, without the ready facilities for camping and day trips that abound around all the other lakes. Foreigners enjoy it for its extraordinary, mountain-ringed setting and superb fishing. The approach from Entre Lagos leads to a tiny settlement at Puerto Chalupa, which has a lovely beach. From the south, the road from Puerto Octay is a 25km (15-mile) drive, with no public transport service. The beautiful campgrounds along the south shore of the lake are also virtually inaccessible without a vehicle.

Lago Llanquihue

Lago Llanquihue is the granddaddy of all the Chilean lakes. It is South America’s fourth-largest, covering some 877 sq km (339 sq miles) and nearly 50km (30 miles) across from Puerto Octay to Puerto Varas on the south shore. The lake has an oceanic feel, with breakers that churn higher in winds or rough weather and mini-climates in its interior that keep boaters and fishermen alert; except for the narrow strip of land between Puerto Varas and Puerto Montt, the lake would be part of the ocean. The enormous national park at the eastern end of Lago Llanquihue, stretching all the way to the Argentine frontier, bears the name of Vicente Pérez Rosales, the promoter of foreign immigration to the region. It was Chile’s first, established in 1926.

FACT

As you walk through the woods of southern Chile, you’ll probably see a brown bird with a rust-colored breast hopping through the undergrowth; it will be a chucao, named for its distinctive call.

Lago Llanquihue is one of the most visited sites in all of Chile, and tours of the district often start in Puerto Montt and then work back toward the north. Puerto Varas $ [map] is the main lakeside resort town. The beaches (the name of one, Niklitscheck, reflects a later immigration of Slavs, especially in the far south) run for several kilometers with rows of shops and excellent restaurants, and plenty of nightlife. The views from Puerto Varas across to Volcán Osorno (2,652 meters/8,701ft) and Volcán Puntiagudo (Sharp-Pointed), 2,190 meters (7,185ft), are breathtaking, and summer activities abound, making it a fun place to hang out. The ease of transport and the plentiful accommodations to suit all budgets and tastes mean that all kinds of travelers gather at night to stroll the beach walks and rub shoulders.

Lago Llanquihue.

© 2009 Richard Nowitz

Peak season is February; the views are just as fine in January, but the maddening tábanos are thickest then – irritating horseflies attracted to dark clothes and shiny objects, which love to buzz around your head in the sunshine. They don’t come out in overcast weather, and since their life cycle is only a month, they disappear in early February. But before that they can easily ruin a day out.

Going east from Puerto Varas the road curves and dips, providing countless views of the lake from every imaginable angle. Winds tend to whip across even on bright, cloudless days, so the air is likely to remain cool and tempt the unwary to overdo exposure to the sun. The notorious deterioration of the ozone layer, which becomes progressively worse as one moves closer to Antarctica, contributes to the potency of the sun’s rays.

Numerous hosterías by the lakeside provide lodging and full meals, but they can be pricey. On a clear day, residents will come down from their rural domiciles and gather in lakefront soccer fields to watch a match in the strong breeze with the sparkling water in the background. Volcán Calbuco (2,015 meters/6,611ft) is quite close on the right. This volcano’s top was blown off in an 1893 eruption, leaving a jagged cone. About halfway to Ensenada is the Río Pescado (Fish River), which, not surprisingly, is famous for its good fishing.

Volcán Osorno and the Saltos del Petrohué.

Jamiemp/Dreamstime.com

Saltos del Petrohué

From Ensenada % [map] most visitors head up the 16km (10-mile) spur to Petrohué, stopping to see the unusual Saltos del Petrohué. These are a series of oddly twisting water chutes formed by a crystallized black volcanic rock that is particularly resistant to erosion. Volcán Puntiagudo’s odd shape is also due to this erosion resistance: its central core is composed of the same crystallized rock which remains unaffected while the surrounding material erodes away. The water of the Petrohué River is bright green due to the presence of algae, a phenomenon repeated in Lago Todos los Santos (All Saints Lake), which begins at the town of Petrohué.

TIP

If you find Chile’s southern seas too cold for swimming, try the lakes where the water is appreciably warmer.

From the falls to the lake the road is cut by several river beds, which will rise suddenly on a warm day with melt from Volcán Osorno. Eruptions from the volcano centuries ago diverted the River Petrohué’s flow from Lago Llanquihue south to Lago Todos los Santos; signs of the earlier lava flows can be observed along with strange vegetation and insect life not found even a few kilometers away. Petrohué itself is nothing but a lodge, a lakeside campground (the fishing is said to be great), and a forest service outpost, but a large modern catamaran leaves from the dock for day trips on the lake. In the height of summer this area is plagued by two types of biting fly – the colihuacho and the petro (Petrohué is a Mapuche word meaning Place of Petros). The only relief from these pests is to shelter in the deep shade of the forests.

Small glaciers atop Volcán Tronador, (Thunder Mountain; 3,451 meters/11,322ft), can be observed en route, and Volcán Osorno is even more imposing from the Lago Todos los Santos side than from Lago Llanquihue. The lake itself is narrow, with forested cliffs rising sharply on all sides. Lunch at touristic Peulla ^ [map] at the other end is expensive and not particularly appetizing. The famous Cascadas Los Novios (Bridal Falls) may be only a trickle if rain has been scarce, and the hamlet can be surprisingly hot but the hiking excursions into the mountains from Peulla are excellent. It’s possible to continue the same day to San Carlos de Bariloche in Argentina by taking the road to Puerto Blest & [map], from where you pick up another boat.

Estuario Reloncaví from the air.

Alan Dykes / Alamy

Estuario de Reloncaví

A turn-off from the road from Ensenada to Petrohué leads to the Estuario de Reloncaví (Reloncaví Estuary), which connects with the Seno de Reloncaví (Reloncaví Sound). Fishing here is not what it used to be after years of commercial exploitation, but there are still plenty of unexplored inlets. This area and the region farther south are sometimes called “continental Chiloé” for the similarity in culture with Isla de Chiloé. As the road winds down the glaciated Petrohué River Valley onto the east shore of the Reloncaví, the characteristic Chilote tiles begin to appear on many of the buildings. These are made from water-resistant alerce, sequoia-related trees that live for hundreds of years and can resist forest fires. The wood is so valuable that alerce stumps are sometimes harvested and split for sale.

TIP

In the peak summer season, leave plenty of time for crossing the Chacao Channel to Chiloé: there can be a long queue for the Pargua-Chacao ferry.

From Ralún, at the mouth of the Petrohué, a bridge crosses the river to Cochamó * [map] farther south, a fishing town which has views of Volcán Yate (2,111 meters/6,926ft), and Puelo ( [map]. These towns are reminiscent of the isolated communities along the Carretera Austral highway, which winds through the largely uninhabited archipelago region in the far south for close to 1,000km (600 miles).

The area from Ensenada north along Lago Llanquihue was covered in an eruption some 150 years ago and nicely illustrates how plant life gradually returns after destruction by a lava flow; the borders of deciduous forest are abruptly marked on either side.

Three kilometers (2 miles) from Ensenada is the road to La Burbuja (The Bubble) refuge on the slopes of Volcán Osorno, well worth the 19km (12-mile) climb. In clear weather, the sunset seen from the top is memorable, and the local refuge/ski center has overnight facilities. The road eases down to the town of Las Cascadas ‚ [map] (The Waterfalls), but there is no public transport for this 20km (12-mile) stretch. Hitchhiking is easier in the afternoon, but never a sure thing. The road has more than the necessary twists and turns – locals explain that the original track was paid for by the kilometer, and their relatives ensured it was as long as possible.

Las Cascadas is the base for an attractive 4km (2.5-mile) hike into the hills, but it’s easy to get lost, so it is advisable to hire a guide from the town.

An Active Landscape

Chile has over 2,000 volcanoes, located mostly in the Andes Mountains, of which over 500 are considered geologically active and around 60 have erupted in the last 500 years. The entire country forms part of the Pacific “Rim of Fire” which stretches along the western coasts of North and South America, west to New Zealand and the western Pacific islands and up through Japan and the Kamchatka Peninsula.

Chile’s volcanoes are doubly dangerous because of their eternal snows, which melt into rapid, devastating mudslides upon full eruption. The lava itself advances much more slowly but burns away everything in its path. These lava “runs” can be observed at the Villarrica and Osorno volcanoes, and you can climb the Villarrica volcano for a peek down at the magma quite near the surface. Although some of the active volcanoes are considered semi-dormant, a strong eruption can always set off a chain reaction of volcanic activity, as happened in the 1960 earthquake.

The lakes are of glacial origin, their basins carved out by advancing ice, then filled by the melting ice as the glaciers receded. There is also evidence of tectonic influence, with earthquakes causing some lake basins to sink further while newly formed volcanoes sometimes shift the course of rivers as they rise up between them.

Volcán Osorno

Volcán Osorno, a perfect, snow-covered cone, dominates the view from the road. Skilled mountaineers can climb to the crater in about six hours, but quickly shifting clouds and hidden crevasses can be deadly even for the expert. Plentiful stories of people being lost there are intended to discourage freelance exploring. It is worth visiting one of the various farms set back up in the hills a few hundred meters, on the pretext of buying homemade cheese or marmalade – you should be able to get a wide vista of the lake and volcano together, and will understand why the original settlers went to the trouble of making these densely overgrown lands habitable.

Some settlers employed Chilotes, mestizo fishermen from Isla de Chiloé farther south, to help with the backbreaking labor, sometimes abusing their trust to trick them out of fair wages. One whispered story even suggests the imported workers were often “lost” in the thick jungle in order to avoid paying them anything. Settlers dragged logs or their farm produce down to a dock to be picked up by the steamboat from Puerto Varas, sometimes going along to the town for provisions. But the frequent lake squalls could lead to financial disaster: in order to avoid capsizing, passengers would have to dump their recently bought goods overboard, package by package.

The only surviving pier from the epoch is at Puerto Fonck on the road that connects Las Cascadas with the road to Osorno. The long stretches of beach from Las Cascadas toward Puerto Klocker and Puerto Fonck are deserted. European settlers did not feel secure in the area until the Mapuche people were finally defeated in the late 1800s.

The pier at Frutillar.

© 2009 Richard Nowitz

Puerto Octay and Frutillar

The idea of Lago Llanquihue as a vacation spot occurred as early as 1912 to a government functionary, Interior Minister Luis Izquierdo, who built a summer mansion on the Centinela peninsula next to Puerto Octay with a group of his friends. The house remains in use today as the Hotel Centinela. Nearby, on the northern lakeshore, Puerto Octay ⁄ [map] is a popular resort town, and a bit less crowded than the southern side of the lake. The road along the lake heading south toward Frutillar has more spectacular views.

On the western shore of the lake, the tidy little town of Frutillar ¤ [map] has a famous classical music festival in the summer. It is actually two towns joined together: Lower Frutillar is 4km (2.5 miles) down a steep incline from Upper Frutillar. There are more houses up above, many of which offer summer lodgings at reasonable rates. Fixed-rate taxis will ferry you up and down if the walk is too tiring. Frutillar and other towns in the area are known for their pretty shingled churches, which often appear in tourist brochures with the lake sparkling in the background.

Osorno

Of all the southern cities, Osorno ‹ [map] is the least interesting, partly due to the strange lack of street life. A business day in Osorno feels like a Sunday, and Sunday feels like a day of national mourning. The town was abandoned after the great Mapuche uprising of 1598, its inhabitants fleeing to establish protected outposts on the ocean inlets just north of Isla de Chiloé. Osorno was not refounded until 200 years later, and it is still more of a market center for country residents than an urban entity. The cattle auction is perhaps its most impressive attraction.

City highlights include the modern cathedral on the Plaza de Armas, and the Museo Histórico (Jan–Feb Mon–Thur 9.30am–6pm, Fri 9.30am–5pm, Sat–Sun 2–7pm; Mar–Dec Mon–Thur 9.30am–5.30pm, Fri 9.30am–4.30pm, Sat 2–6pm, closed Sun; free), with displays on Osorno’s history and the German arrival. Osorno’s wooden houses have sharply angled roofs to handle the rain and snow, and when the storm clouds begin to threaten, the place has the air of a city in Quebec or northern New England. The 18th-century Fuerte Reina Luisa fort is derelict – the one at Río Bueno, 30km (19 miles) north, is better preserved. It has a good view of the river, also known as El Gran Río, which carries off the water of four lakes (Maihue, Ranco, Puyehue, and Rupanco) – making it the second-largest in Chile.

Salmon farm off Chiloé.

Estudiomj/Dreamstime.com

Salmon Clean-up

Over the past 20 years, southern Chile has seen the development of a new export industry – salmon farming – and the country now rivals Norway on world markets. The salmon industry’s development has increased the number of jobs in a region where employment was previously scarce and explains the rapid growth of Puerto Montt, with its vast salmon processing plants, as well as Puerto Varas, where most of the industry’s executives prefer to live.

But the environment suffered. The once-pristine lakes and sheltered sea bays have been polluted with salmon feed, antibiotics, and organic waste. An outbreak of ISA (infectious salmon anemia), a highly contagious salmon virus disease, which began in 2007, however, forced the industry to rethink its practices. As well as reducing the density of seawater cages – as many as a million fish can be fattened in one bay – producers are increasingly starting to use on-land plants, rather than lakes, for hatching and breeding – partly because of environmental pressures, but also because the contamination the industry itself has caused now poses a risk to the health of juvenile fish.

Regulation on where new farms can be located and the distance between them has also been tightened. Partly as a result, the industry is now expanding south into the Aysén and, even, Magallanes Regions, away from the Lake District and Chiloé where its development began.

Puerto Montt

Around 110km (68 miles) farther south is the bustling, windy city of Puerto Montt › [map]. Connected by rail to the rest of Chile in 1912, it became the contact point for the rest of the south. It remains so to the present day, despite the loss of its railway line. It is an important fishing center; seafood at the harbor of Angelmó is famous. The port was completely destroyed in the earthquake of 1960. Boats leave from here for the long, slow trip down through the southern archipelago. (Puerto Chacabuco requires 22 hours, Puerto Natales three days.) The port is protected from the strong winds by Isla Tenglo.

Harbour, Puerto Montt.

29061965mv/Dreamstime.com

From the hills above the city there are fine views of the entire Seno de Reloncaví. Local boat trips can be arranged in Puerto Montt. From Chamiza, to the east of the town, it is possible to get close to Volcán Calbuco on the southern side of Lago Llanquihue. German settlers built an interesting Lutheran church in Chamiza next to two giant saav trees. Parque Nacional Alerce Andino has good facilities, and Lago Chapo is off the usual tourist beat. A peaceful rural site situated near Puerto Montt threw the archeological world into a frenzy, pushing back the possible date of human arrival in the Americas by thousands of years. During the 1970s, scientists discovered that the area around the Chinchihuapi Creek, known as Monte Verde, held human remains dating from 12,500 years ago. In 1998 more remains were found at the site, which suggest possible human occupation 33,000 years ago.

FACT

Until 1930, the little fishing village of Maullín could only be reached by boat. Its name means “full of water.”

Southwest of Puerto Montt are the port of Maullín and Carelmapu fi [map] one of the oldest settlements, dating from the Spaniards’ flight after their defeat by the Mapuches around 1600. On its rough beaches, the original wild strawberries from which commercial strawberries were developed still grow, as in many other remote places in the south of Chile. An alternative route is the road that follows the bay southwest from Puerto Montt to Calbuco. This offers distinctive views of the volcanoes toward the north. Calbuco fl [map], like Carelmapu, predates Puerto Montt by some 250 years.

German Settlers

During the 19th century, millions of people fled famine and hardship in Europe and came to the Lake District in search of a better life.

German immigration to Valdivia occurred in two periods: a minor influx in the first half of the 19th century and the more important wave between roughly 1885 and 1910. The immigrants played an important role in commerce and industry, using technical knowledge brought from the old country. Some cultivated their new lands, although climatic conditions were not ideal. Others arrived as ironsmiths, carpenters, tanners, brewers, watchmakers, locksmiths, and tailors.

Chile in 1850 was just emerging from three decades of political anarchy and economic stagnation, and distant provinces like Valdivia were left largely to their own devices.

By 1900, a traveler claimed that upon entering Valdivia, he could not believe he was still in Chile. Many of the tradesmen had converted their shops into factories. Valdivia became Chile’s prime industrial center, with breweries, distilleries, shipbuilding, flour mills, tanneries, 100 lumber mills and, in 1913, the country’s first foundry. Furniture-making was stimulated by the immense availability of beautiful native woods.

The wealth of the Germans of Valdivia was legendary in Chile until their luck changed, starting with the imposition of a heavy liquor tax in 1902 at the behest of Central Valley vintners. Unfavorable trade conditions wiped out much of the leather market. A great fire laid waste to the city in 1909, while the local merchant class was superseded by mine and estate owners from farther north, closer to the byzantine politics of the capital.

Puerto Montt and Osorno

Beginning in the mid-19th century, the region around Lago Llanquihue was also heavily settled by German immigrants, who disembarked at what is now the Seno de Reloncaví. Vicente Pérez Rosales, the indefatigable promoter of colonization in southern Chile, organized a solemn ceremony to establish Puerto Montt formally with a group of the recent arrivals, none of whom understood a word of Spanish. According to an account of the ritual, led by a Catholic priest, the Protestant settlers interrupted at what seemed to them an appropriate pause with a rousing chorus of Hier Liegt vor Deiner Majestad (Here Before Your Majesty). Despite the idiomatic complications, Pérez Rosales’s project was a success in the long run.

Osorno is well known as having been settled by Germans. However, despite the many German street names, the immigrants never actually numbered more than 10 percent of the total population of the region.

Chileans were also drawn to these new lands, generally uneducated and destitute people hoping to make a new start. The foreigners quickly established themselves as the dominant class, employing the mestizo citizens and directing economic development.

Chile’s largest remaining concentration of Huilliches (southern Mapuches) is to be found in communities scattered between Osorno and the coast, around towns like Puaucho and San Juan de la Costa. Although educational and healthcare facilities have improved in recent years, this is still one of Chile’s worst pockets of rural poverty. Huilliches can be seen trading their cash crops in the market in Osorno, which is a drab city compared to more prosperous and sophisticated Valdivia.