Isla de Chiloé

This large, rainswept island is a culturally distinctive area with its own music, dance, and craft traditions, and a wealth of spellbinding myths and legends.

Main Attractions

For a moment you think you’ve misheard, that someone has simply pronounced the word “Chile” and for some peculiar reason your ears have given it an extra “o.” To some extent Chiloé is Chile in miniature, a peculiar time capsule that contains some of Chile’s best and harshest traditions, shaping them into song, dance, crafts, and a mythology that has become one of the main strands of the country’s national identity. Much of “Chilean” folk music and dance was born in Chiloé’s gentle summer fogs and wet winters.

December, January, and February are the better months for a visit to Chiloé, because the warmer summer weather makes it easier to travel within the main island and across to some of the smaller islands. In recent years, Chiloé has become something of a standard pilgrimage for the young and the not-so-young, so you may meet more people from Santiago than from the islands.

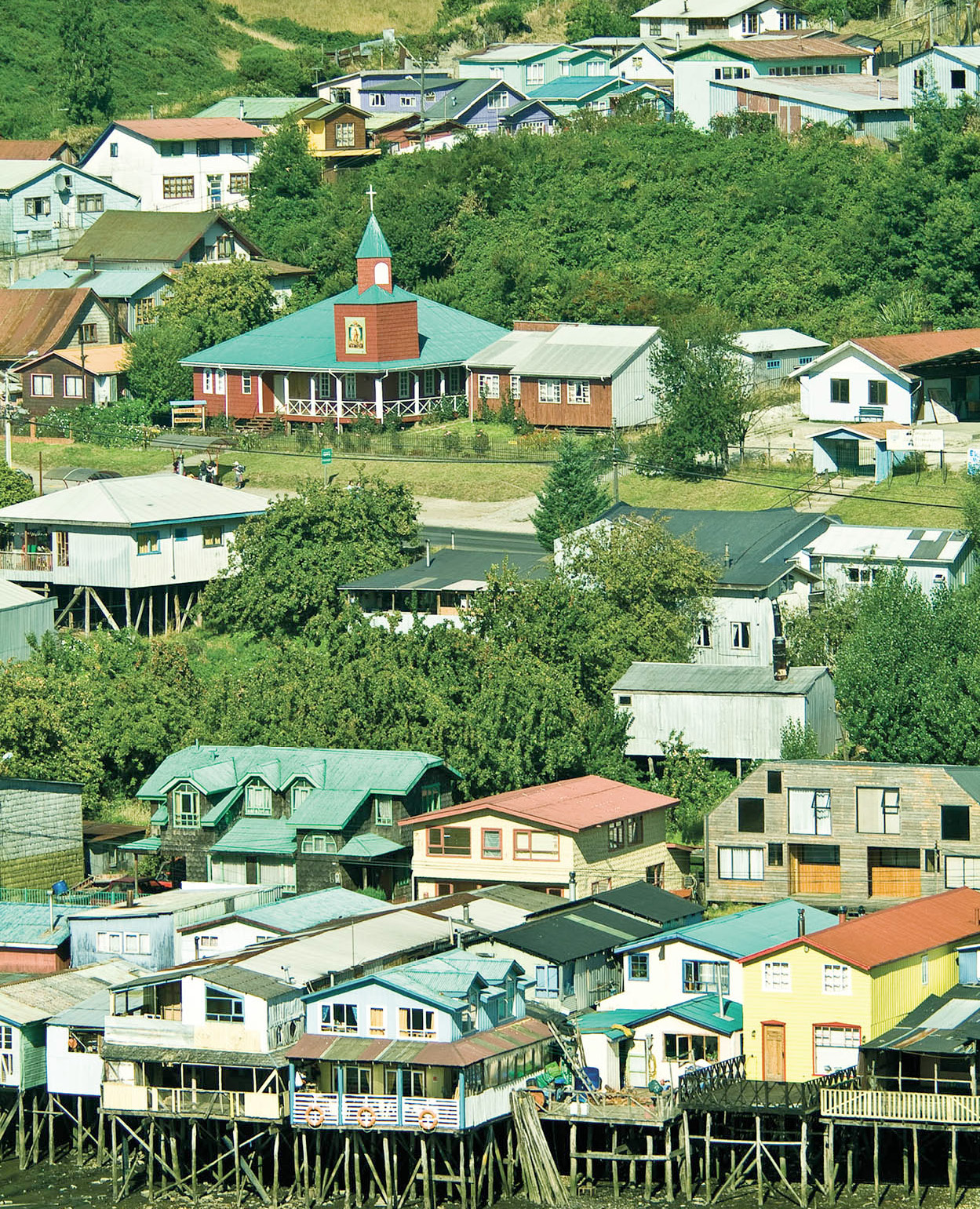

Palafitos (houses on stilts), Castro.

Abraham Nowitz

Chiloé’s flood myth

A Mapuche legend tells the story of what may have been the formation of Chiloé as witnessed by the Mapuche and Chono peoples long before the Spanish reached the continent. It tells how the twin serpents Cai Cai and Tren Tren do battle. Cai Cai, the evil one, who has risen in rage from the sea and flooded the earth, assaults Tren Tren’s rocky fortress in the mountain peaks, while the people try in vain to awaken the friendly serpent from a deep sleep.

Meanwhile Cai Cai has almost reached Tren Tren’s cave, swimming on the turbulent waters. Cai Cai’s friends, the thunder, fire, and wind, help her by piling up clouds to bring rain, thunder and lightning.

Pleas and weeping don’t wake Tren Tren. Only the laughter of a little girl, dancing with her reflection in the sleeping serpent’s eye, arouses her, and she responds with a giggle so insulting that Cai Cai and her stormy friends fall down the hill.

Ancud.

© Arco Images GmbH / Alamy

Cai Cai charges again, all the more furious, shattering the earth and sowing the sea with islands. She makes the water climb ever higher, and almost submerges the mountain where her enemy lives, but Tren Tren arches her back, and with the strength of the 12 guanacos in her stomach, she pushes the cave ceiling upward, so that the mountain grows toward the sky. Cai Cai and her friends keep bringing more water and Tren Tren keeps pushing her cave roof higher until the mountain reaches above the clouds, close to the sun, where the evil serpent cannot reach it. Cai Cai and her servants fall from the peak into the abyss, where they lie stunned for thousands of years.

The waters gradually recede, and the people are able to return to their lands, untroubled by either of the giant serpents, who continue sleeping. However, sometimes, it is said, Cai Cai has nightmares, and an island appears in the ocean or the earth trembles a little. The legend may tell the story of an ancient earthquake which was accompanied by tidal waves and flooding, but it is also remarkably similar to scientific accounts of how the peculiar attributes of the area came about.

The Pargua−Chacao car ferry.

Luis Davilla/Getty Images

Birth of an archipelago

The scientists explain that over thousands of years, two giant tectonic plates forming part of the earth’s crust clashed, producing the volcanoes characteristic of mainland Chile: Hornopirén, Huequi, Michimahuida, and Corcovado. During the Ice Age, glaciers bore down upon the Central Valley region, carving a gap through the coastal mountains and pushing the valley farther and farther below sea level.

When the glaciers began to melt at the end of the Ice Age, the ocean poured through the openings located at the north and south ends of what is now the main island of Chiloé, to create the interior sea that divides Chiloé from the mainland, turning what was previously the coastal mountain range into the series of islands that form the archipelago of Chiloé. Toward the center of Isla Grande de Chiloé, where the lakes of Huillinco and Cucao cut partially through the island’s mountain range, the land drops to sea level, and many islanders fear that Chiloé may one day be cut in two.

A young Chilote in Castro, one of Chile’s oldest towns.

© 2009 Richard Nowitz

Chiloé’s Isla Grande (main island) is the second-largest island in Latin America, after Tierra del Fuego. Like a great ship moored off the Chilean coast it seems to float, surrounded by several smaller constellations of islands called the Chauques, Quenac, Quehui, Chaulinec, and Desertores. Some of these islands are so close to each other they are joined at low tide. The low mountains along the west coast of the main island are nevertheless high enough to stop the damp winds blowing off the Pacific, creating a slightly drier microclimate along the interior sea, where virtually all the settlements are located.

The interior sea, generally calm – at least as seen from the shore – can be difficult to navigate, especially for the many Chilotes who still rely on small rowboats or launches. As the tides roar in through the tiny channel of Chacao in the north (crossed by the mainland ferry), they eventually meet and clash with the tides pouring through the channel to the island’s south, creating huge whirlpools and waves that have been identified as a potentially rich source of tidal-generated electricity. In Cucao, on the Pacific coast, the difference between high and low tides is 2.5 meters (8ft), while in Quemchi it is 7 meters (23ft), because of the shallowness of much of the interior sea. These powerful tides leave shellfish and fish, a major source of food for the islanders, trapped on the beaches and in sea pools.

Dalcahue woman, Chiloé Island.

© Wolfgang Kaehler / Alamy

The making of the Chilotes

The first known inhabitants of the islands of Chiloé were the Chonos, a tough, seafaring people who have gone down in history for the creation of the dalca, a small, canoe-like boat built by binding several rough-hewn planks together. For centuries, the Chonos guided the Spanish and other adventurers through the intricate channels and fjords which honeycomb Chile’s southern shores. They spoke a different language from the Mapuches or Huilliches (southern Mapuche), who began to invade the islands.

FACT

The typical Chilote boats use a cross-shaped anchor, made with a stone and two planks of wood.

These invasions forced the Chonos to migrate farther and farther south. In the 1700s, the Jesuits pushed the Chonos and the Caucahues, a separate native group who had not been integrated into the Mapuche tribe, into small reserves on Isla Cailín, south of Quellón, and later the Chaulinec Islands, where they eventually mixed with the other inhabitants. The Jesuit mission on Isla Cailín was the southernmost chapel in the Christian Empire.

When Alfonso de Camargo became the first European to see Chiloé in 1540, the archipelago’s inhabitants were a mixture of Chono and Mapuche living scattered along the coast, which was at once their main highway, source of food, and the cradle for a wealth of legends and oral histories which are the backbone of Chilote culture to this day. The homes in which they lived were straw rucas, clustered near beaches and woods in groups of up to 400 people and known as cabís, led by caciques or chiefs. Using wooden tools, they farmed potatoes and corn in fields protected by fences which were woven using basket techniques, and they reaped the rich harvest of shellfish along the shores.

Serfdom and rebellion

Thirteen years later Francisco de Ulloa’s expedition formally “discovered” the islands, and 14 years after that, Martín Ruiz de Gamboa officially took possession of them, calling them Nueva Galicia. On February 12, 1567, he founded the city of Santiago de Castro and for the next 200 years the Spaniards divided up the available land – and the people living on it – in what became known as the encomienda system, a kind of serfdom. The idea was that the native peoples worked for free in order to “pay tribute” to the king of Spain. This native labor system was used in the mining of gold in Cucao, the weaving of woolen cloth and the logging of alerce, a tough, fine wood native to Chile (which is today in danger of extinction). In the early years, the products of Chiloé brought considerable wealth to the Spaniards who had taken possession of the land, but desperate poverty to its people.

FACT

Lago Cucao gets its name from the “cuca” heron that frequents its shores.

In 1598, when the Mapuche communities of Carelmapu and Calbuco on the mainland rebelled against the Spanish invaders, the survivors retreated to Chiloé, where they established towns in 1602. The people of Chiloé twice joined forces with “pirates,” destroying Castro with Baltazar de Cordes in 1600 and attacking Carelmapu and later Valdivia, across the channel, with Enrique Brouwer in 1643. In the centuries that followed, the Spanish and the Mapuche-Chonos of Chiloé lived in virtual isolation and extreme poverty, with occasional visits from Spanish ships sent from Lima, Peru, sometimes as many as three years apart. Despite this neglect, Chiloé became a royalist stronghold during the wars of independence in the early 19th century. The governor of Chile fled to Chiloé, and despairingly offered the island to Britain. The offer was declined, and Chiloé surrendered to the mainland republic in 1826.

FACT

The island of Chiloé was once covered in impenetrable woods, which have gradually been cleared to make way for agriculture.

Over the centuries the two races, Spanish and Mapuche-Chono, fused, preserving much of the native languages and customs. The Chilotes all wore the same clothes and suffered the same hardships, creating a sense of social equality unusual in the Spanish Empire. Settlement continued along the coast until the early 1900s, when lands were given to German, English, French, and Spanish “colonists,” and the building of a railway in 1912 between Ancud and Castro finally opened internal communication between Chiloé’s two main cities.

Guarding the clam catch, Ancud.

Abraham Nowitz

A distinct culture

Today the Chilotes continue to be a proud, independent people, clearly distinguishable from their fellow Chileans, with their own dialect mixing influences from 16th-century Spanish with many indigenous words, and a rich tradition of music and dance beloved throughout Chile. The tragic poverty of the early colonization, which forced many men to take seasonal work on the sheep farms of the Magallanes area and even in Argentina, has now given way to greater prosperity, born of tourism and the introduction of salmon farming.

The one great weakness of the Chilotes is the game of truco, which is played with the Spanish 40-card deck. Truco, which roughly translated means “trickery,” is an extraordinary gambling game divided into two parts, the envío and the truco itself. The cards are half the game; the other half is the skill and imagination of the players who bluff and jest, using rhyming couplets laden with double meanings. Today, you are as likely to see a lively game of truco on a ship at Punta Arenas as in a Chilote bar. And the Chilotes who’ve gambled away a season’s earnings on the sheep ranches and are unable to return home are legendary. This forced migration of working men has also given rise to the image of the Chilote family as a virtual matriarchy of distant, sometimes almost mythical men, and strong women raising their children, their livestock and tending their crops, keeping the island alive.

The wooden interior of the Iglesia San Francisco in Castro.

© 2009 Richard Nowitz

It was during the 200-year period when the Spanish were barred from the Mapuche lands in mainland Chile that the Jesuits began the evangelizing activities which left an enduring mark on the islands’ legends and villages. Some of the most strikingly beautiful characteristics of Chilote architecture are the wooden chapels built during the Jesuits’ stay, many of which survive to this day. Between 2000 and 2001, Unesco’s World Heritage Committee declared 16 of these chapels sites of universal value on the grounds that they represent the only Latin American example of a rare form of ecclesiastical wooden architecture.

FACT

There are more than 150 churches and chapels in Chiloé. The oldest churches were built entirely of wood, using wooden plugs instead of nails, and provide some of the world’s few remaining examples of 18th-century wood architecture.

The chapels, which often stood completely alone on the coast unaccompanied by human habitation, were built as part of the Jesuits’ “Circulating Mission.” This consisted of a boat manned by two missionaries who started their annual rounds from Castro with religious ornaments and three portable altars, complete with a “Holy Christ” to be carried during ceremonies by the caciques (chiefs), a “Holy Heart” to be carried by children, a “Saint John” to be carried by bachelors, a “Saint Isidore” for married men, “Our Lady of Suffering (Dolores)” for single women, and “Saint Notburga” for married women.

To this day, a fiscal, a sort of native priest, has the custody of chapel keys, and in August people from nearby islands gather on Isla Caguache to celebrate their religion with ceremonies similar to those initiated by the Jesuits and modified by later Roman Catholic missions. The chapel of Vilupulli, near Chonchi, continues to stand alone, with no human settlement around it, exactly as the chapels did in the 1700s. These chapels are an interesting example of the Chilotes’ outstanding ability to absorb foreign cultures without losing their own identity. Their design is strongly influenced by German architecture of the period, because several of the Jesuits were from Bavaria.

The tejuelas or wooden shingles commonly used to roof buildings throughout southern Chile, and which are one of the most striking characteristics of homes in Chiloé, were also a German idea, brought by the colonists who originally settled in Llanquihue and Puerto Montt on the mainland. The visible part of the tejuela is approximately a third of the total length, as they overlap so well that these buildings are extremely resistant to the heavy rains of the region. Before the tejuelas were introduced, Chilote homes usually had roofs of straw, similar to those of the Mapuches’ rucas, and also extremely resistant to rain.

A tradition of handicrafts

For centuries, the women of Chiloé have spent the harsh winters producing clothing and household items. Different parts of the islands are associated with different crafts. The small town of Chonchi (south of Castro) is known for its woven wool products, especially blankets and ponchos, as well as licor de oro, a liqueur made with saffron. Quellón 1 [map] is famous for its ponchos, which are resistant to rain because the wool used for making them is raw and full of natural oils. On Isla Lingue, across from Achao, baskets are woven from local fibers, although some have fallen into disuse owing to the difficulty of working with them. Many of the islands’ legends have been woven into decorative objects from all areas of Chiloé.

FACT

On Sunday mornings, there is a traditional market by the dock in Dalcahue 2 [map], where hundreds of craftspeople from all over the archipelago still gather to sell their wares. They also prepare traditional Chilote meals, particularly the curanto, a concoction prepared over a fire built in a hole scooped out of the earth, containing a variety of shellfish and meat and served with milcao, a traditional flatbread made with grated potatoes. The traditional woven fences of the Mapuche-Chonos can still be seen separating livestock from planted areas in some parts of the islands, and the birloche or trineo, a sled-like vehicle towed by oxen, continues to be used on several of the smaller islands.

Keep your eye out in markets and fairs for the almudes, wooden boxes of a fixed size, still used to display a seller’s wares. The almud is also a unit of measurement, and the boxes have the peculiarity of measuring one almud on one end and half an almud on the other. Their origin is Spanish. Stone mills introduced by the Jesuits can be seen in several Chilote museums, and they are still in use in some areas between Castro and Dalcahue. In February, wooden chicha (cider) presses are still very much in evidence, pressing the sweet juices out of apples piled in traditional baskets. Hanging in the windows of many houses you’ll see woolen socks or ponchos, or other handmade items for sale. If you’re lucky you may also get a glimpse of a Chilote loom, which is horizontal and nailed to the floor. It is still used by the artisans, who must kneel to work it.

For Chilote sweaters, the women shear the sheep, clean and wash the wool by hand, dye it with colors prepared from local herbs, and spin it using a simple spindle which twirls on the floor.

Holding on to the past

Chiloé is in many ways as mysterious, as long-suffering, and as contradictory as it has been for most of its history. Modern fish-processing plants and salmon farming have provided more employment. At the same time, pollution and overfishing of coastal waters are now problems.

Other Chilotes have tried to eke out a living from fishing, with mixed results, and developmental agencies have created programs for improving Chilote agriculture, marketing and handicraft techniques. Even as modern factory ships sail under foreign flags, just outside Chile’s 322km (200-mile) limit, the Chilotes themselves continue to live – and die – by traditional rowboats and small motor launches. Chilote culture itself – the music, poetry, and stories – is increasingly packaged for a burgeoning tourist industry, a process which tends to create and preserve caricatures devoid of their original meaning. Like similar attempts in other parts of the world, this has harmed as well as helped the local economy.

Chilote cultural activity is on view during the Festival Costumbrista, held in the second or third week of February in Castro and other towns, and during local summer events.

Ancud and Castro

Ancud and Castro, the main island’s two cities, provide good bases for exploring the archipelago. Until 1982, Ancud 3 [map], which has a population of 27,000, was the capital of Chiloé. The city was an international port until the beginning of the 20th century, and it retains a peculiar mixture of traditional Chilote buildings, docks, and plazas combined with more modern signs and structures.

Ancud’s central plaza is flanked by the cathedral, government buildings, and the Museo Regional de Ancud (Jan–Feb 9.30am–8pm, Sat–Sun 9.30am–7.30pm, Mar–Dec 10am–5.30pm, Sat–Sun 10am–2pm; charge), which contains exhibits about Chilote culture and mythology.

If you have a vehicle, you can enjoy a lovely drive along the Costanera (coast road), with a view of the Gulf of Quetalmahue. Lining the shore are the older, often impressive houses of Ancud’s wealthier citizens.

Potato harvest, Teuquelín island.

© Aurora Photos / Alamy

To Bridge or Not to Bridge

For the past decade, argument has raged over the possible construction of a bridge to link Chiloé to mainland Chile. The idea was first mooted in the 1970s but only began to be seriously considered in the early 2000s when then President Ricardo Lagos proposed construction of a suspension bridge – the so-called Bicentennial Bridge in reference to Chile’s celebration of the 200th anniversary of its independence in 2010 – across the Chacao Channel. Stretching 2.6km (1.6 miles), this would be the longest of its type in South America but, after estimates of its cost reached almost US$1 billion, the project has been successively postponed. Moreover, although it would reduce the crossing to a matter of minutes as compared to at least half an hour on the current ferry service, not everyone in Chiloé wants a bridge. Many fear the cost of the tolls (although subsidized by the government, the bridge would be privately built and operated), and others are wary of the impact on their traditional way of life. Many think that money would be better spent on public infrastructure within the archipelago and, for example, better local health services which would, in turn, reduce the Chilotes’ need to cross to the mainland.

The Mirador Cerro Huaihuén (a lookout point) affords breathtaking views of the city and across the Chacao Channel toward the mainland. By following the Costanera, then Bellavista and San Antonio northward, you’ll quickly reach Fuerte San Antonio, which was built in 1770. On January 19, 1826, it became the last Spanish garrison to surrender to the wave of independence which had swept South America. Ancud then became the focus for colonizing expeditions aimed at southern Chile, including one that settled possession of the Strait of Magellan in 1843. In the late 19th century, Ancud boomed with the whale and wood industries, and newly arrived settlers from Europe, primarily of German origin. However, when the railway extended to Puerto Montt in 1912, Ancud lost its importance, and in 1982 the trade and shipping center Castro became the capital of Chiloé.

Near the waterfront, craftspeople set up stalls selling mostly woolen goods. At the covered fruit and vegetable market on Calle Pedro Montt, look out for the blue, black, and red varieties of potato that are native to Chiloé.

An interesting side trip from Ancud is a visit to the oyster beds at Caulín. To get there you must travel back along the highway toward the ferry’s arrival point at Chacao, and then turn left toward Caulín at Km 24, where you can enjoy fresh oysters at reasonable prices, before spending an afternoon on the beach or heading back to Ancud.

If you drive south from Ancud and then west, you’ll find good fishing at the refugio (refuge) at Puerto Anguay, as well as several good places to picnic. Along the way, look out for the Butalcura River Valley, with great patches of dead trees in the water where the 1960 earthquake caused the earth to collapse.

Castro

Castro 4 [map] has a population of about 29,000, and is located about 90km (56 miles) to the south of Ancud. Although it is technically one of Chile’s oldest cities, having been founded in 1567, Castro suffered so many attacks and privations that there are few signs of its antiquity within the city itself. On parts of the waterfront are palafitos, Chiloé’s distinctive wooden homes on stilts.

It’s best to see Castro on foot, strolling from the Plaza de Armas with its painted cathedral shoreward to enjoy the market area with its lively crafts fair, then back up the hill toward the mirador (lookout) with its statue of the Virgin and its bird’s-eye view of the city’s cemetery, piled high with conventional gravestones and small structures resembling houses that shelter the city’s dead.

Castro’s Museo Regional (Jan–Feb Mon–Fri 9.30am–7pm, Sat 9.30am–6.30pm, Sun 10.30am–1pm; Mar–Dec Mon–Fri 9.30am–1pm and 3–6pm, Sat 10am–1pm; voluntary contribution), is a good introduction to the archipelago’s history and is packed with wooden fishing and farming implements.

The plaza is also the focal point for the Festival Costumbrista, a celebration of Chilote customs, food, and crafts, which takes place in February. The Museo de Arte Moderno (Jan–Feb daily 10am–6pm, closed Mar–Dec except for special exhibitions; voluntary contribution) has an excellent collection of contemporary Chilean work. Set on a hill just outside the town, it also provides a spectacular view of the interior sea and of the snow-capped mountains across on the mainland. The building, constructed of Chiloé’s traditional wood, has won architectural prizes.

Palafitos, traditional wooden houses on stilts.

Abraham Nowitz

Exploring the islands

From Castro you can travel up the shore of Chiloé’s interior sea to visit Dalcahue, Llaullao, and, on Isla Quinchao (accessible by ferry), the small towns of Curaco de Vélez – famous for its oyster beds – and Achao 5 [map]. Achao’s 18th-century church of Santa María is built entirely of cypress and alerce. Farther along the island highway is Chiloé’s largest church, Quinchao, which was built in the 18th century and refashioned according to neoclassical ideas at the end of the 19th century. While driving around the area, keep an eye out for the traditional woven fences.

TIP

If you visit Curaco de Vélez, take a look at the stone mills which are still installed on the Los Molinos brook.

Chonchi 6 [map], about half an hour south of Castro, is a small town built on such a steep incline that it is also known as the “Ciudad de los Tres Pisos” (Three-story City). Local handicrafts abound, and cardboard signs advertise the famous licor de oro. Near Chonchi it’s possible to catch a ferry to Isla Lemuy 7 [map] or head farther south to Queilen 8 [map]. Parque Nacional Chiloé can be reached by traveling across the island toward Cucao, one of only two towns on the Pacific side of Isla de Chiloé. It’s a good place to hike or camp, with a long and wave-pounded beach.

Restaurants

Apart from its hotels, Chiloé has few smart restaurants, but is full of waterfront cafés with wonderful views, that serve generous portions of freshly caught fish and shellfish. They are homely but generally reliable, and very modest in price. In some of the larger towns, there is also a smattering of New Age cafés, run mostly by foreigners. The stalls and makeshift restaurants at the Festival Costumbrista, held every year in February, are an ideal place to try local specialties such as curanto (meat and vegetable stew), milcao (traditional flatbread), and the different types of native potato.

Ancud

La Botica del Café

Pudeto 277

Tel: (065) 629 650

Open in the mornings, afternoons and evenings but closed at lunchtime. A great place for coffee and cakes or a snack.

Mercado de Ancud

Dieciocho s/n

Ancud’s old market, not to be confused with the covered fruit and vegetable market on Calle Pedro Montt, is a great place for a cheap and excellent fish lunch.

Castro

Costanera s/n

Castro’s waterfront crafts market has smarter seafood restaurants (palafitos) than the market in Ancud and as a result the prices are slightly higher, although not prohibitively so.

Chonchi

Lef

Km 35 Pan-American Highway

Tel: (09) 9431 3091

This restaurant in the Espejo de Luna hotel is open daily for lunch and dinner; its spectacular design incorporates the upturned hull of a Chilote boat.