Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum c. 2400 BCE

What are the earliest ‘gay lives’ recorded in history? The question is silly. As even those who have engaged in casual reading of scholarship on sex know, ‘homosexuality’ as a term did not emerge until the 19th century. The ways in which people thought about sex and sexuality – and possibly the ways in which they had sex – varied greatly over time and from place to place. It is probable that some men in almost all cultures have experienced an emotional and physical desire for other men, just as some women will also have felt intimate affection, romance and lust for others of the same sex. Exactly what this meant to them and to others in their societies is seldom entirely clear. A wealth of sources exists that testify to same-sex connections, but the question of how to interpret those documents and artefacts continues to exercise scholars.

One intriguing and very ancient instance of some sort of intimacy between men dates back to 2400 BCE, during the 5th dynasty in Egypt. In 1964 archaeologists discovered a previously unexplored tomb in Saqqara: the burial site of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep. Several carvings on the walls showed the men looking each other steadily in the eyes, holding hands and locked in an embrace: Khnumhotep’s arm was around his companion’s shoulder, and Niankhkhnum, in turn, was grasping the other’s forearm. The inscriptions identify them as ‘royal confidants’: one man was a manicurist to the king, and the other the inspector of manicurists at the royal palace. Other images show the men fowling and fishing, and gathered in the company of their wives and children.

Egyptologists differ in their interpretation of the tomb figures. Some see Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum as twins, or brothers, or just friends who wished to continue their friendship in the afterlife. There has also been speculation that the carvings reveal a same-sex relationship of a different order. One historian, Greg Reeder, points out that the pose of two men gazing into each other’s eyes was uncommon in the iconography of the time; that their embrace is particularly intimate; and that the gestures the two men use follow the artistic conventions that generally unite a husband and wife. Khnumhotep’s and Niankhkhnum’s spouses seem to play a lesser role in the monument’s images than might be expected.

It was assumed that men would marry and procreate, but the Egyptologist R. B. Parkinson has inventoried various references to homosexuality in the Egypt of the pharaohs. Official pronouncements expressed disapproval of sex between men (especially the behaviour of the passive partner), while literary texts were somewhat more ambiguous, sometimes revealing good-natured caricature and even humour. ‘How lovely is your backside!’ remarks Seth to Horus in one tale, in what Parkinson calls a very old ‘chat-up line’. Horus’s mother, the goddess Isis, warns him against having sex with his friend. Yet it is written in the so-called Pyramid Texts – Egypt’s oldest religious writings – that Horus and Seth engaged in reciprocal anal intercourse, even if their coitus is described as injurious.

Whether Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep were blood relatives, companionable colleagues or lovers is unimportant. They are worth recalling because of the very indefinable nature of their relationship – an illustration of the porous boundaries in many cultures between affection, friendship, intimacy, and sexual yearning and its realization. In ancient Egypt, commissioning a tomb and planning its decoration counted among the essential acts of a man’s life. In the survival of these carvings for over four millennia, the men’s wish to be remembered together has been fulfilled; their names mean ‘joined to life’ and ‘joined to the blessed state of the dead’.

David and Jonathan 11th century BCE

Many specialists of biblical exegesis (including believers in the Judaeo-Christian deity), as well as freethinkers, reject the historicity of the Scriptures. Historians and archaeologists have found so many discrepancies between the narrative and other evidence that, for some, it is difficult to believe what generations of Jews and Christians have considered the inspired word of God, and what fundamentalists still claim as literal truth. Yet even those who do not accept their veracity can read the stories as literary creations of power and drama.

The First Book of Samuel tells of Saul, the first king of the Israelites. After a battle captained by his son and heir apparent, Jonathan, Saul refuses God’s order to kill the vanquished – to ‘slay both man and woman, infant and suckling, ox and sheep, camel and ass’. In response, God announces to his prophet that he will choose another as Saul’s successor, an obscure young shepherd named David. Saul, meanwhile, falls into a great depression and summons the shepherd, who is renowned for singing and harp-playing. The King James Bible describes him as ‘ruddy, and withal of a beautiful countenance, and goodly to look to’; Saul ‘loved him greatly’, and David becomes his court musician and armour-bearer. With battle between the Israelites and Philistines re-engaged, David, though too young to be a regular soldier, distinguishes himself by felling the giant Goliath with a well-aimed stone from his slingshot. Jonathan befriends the hero: ‘the soul of Jonathan was knit with the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul … Jonathan stripped himself of the robe that was upon him, and gave it to David, and his garments, even to his sword, and to his bow, and to his girdle’. Saul becomes jealous at the acclaim awarded to David and, again struck with depression, twice tries to kill him; he recovers, however, and gives David command of a thousand men and his daughter’s hand in marriage. As bride-price, Saul asks David for a hundred foreskins of the Philistines, covertly hoping that David dies in battle. When a victorious David brings the prize, Saul’s daughter weds him.

Saul then tries to persuade Jonathan to kill David, ‘but Jonathan Saul’s son delighted much in David’. He reveals the plot and ably brings Saul to a change of heart. The good relationship between king and vassal is not to last. Further victories reawaken Saul’s ire, he again tries to down David with his javelin, then attempts to have thugs murder him. David takes refuge with the prophet Samuel, but meets secretly with Jonathan – ‘thy father certainly knoweth that I have found grace in thine eyes’. Jonathan proposes to sound out his erratic father and, if danger still looms, help David to escape. The two swear loyalty.

David and Jonathan, by Cima da Conegliano, c. 1505–10 (National Gallery, London)

When Saul asks after David, Jonathan reports that he has gone home to Bethlehem for a sacrifice. ‘Saul’s anger was kindled against Jonathan’, and he charges: ‘Do not I know that thou hast chosen the son of Jesse to thine own confusion’, attacking his own son with the handy javelin. The next morning, by a prearranged signal Jonathan warns David, who emerges from hiding for a farewell before his flight: ‘they kissed one another, and wept one with another’. David escapes into the wilderness, with Saul’s agents in pursuit, but rejoices in the occasional secret meeting with Jonathan. David refuses a chance to kill Saul, only cutting off the bottom of his robe because he will not slay his king, then confronts Saul with deference. Reduced to tears, Saul guarantees his goodwill.

Soon the volatile Saul mounts a further assault. David gives up another opportunity to kill his nemesis, and there is reconciliation. In renewed warfare, the Philistines get the better of the Israelites, take David’s two wives captive, kill Jonathan and his brothers, and wound Saul, who commits suicide to avoid capture. A distraught David, hearing of Jonathan’s death, rends his clothes, weeps and exclaims: ‘O Jonathan, thou wast slain in thine high places. I am distressed for thee, my brother Jonathan: very pleasant hast thou been unto me: thy love to me was wonderful, passing the love of women.’

David fulfilled his destiny to become the Jewish king and to sire a dynasty that supposedly stretched down to Jesus. The tangled story of his relations with the half-mad (or demonically possessed) Saul is the stuff of power politics, conspiracies, warfare, plunder, alliances and rivalries for a crown. Some scholars thus have argued that the oaths between David and Jonathan, the love they declare and the feverish nature of their friendship, have more to do with Near Eastern politics and rhetoric than with any homoerotic bond.

Nonetheless, the story has resonated loudly in the homosexual imagination. The shepherd became a figure of legend and art, notably in Michelangelo’s larger-than-life marble in Florence, the Renaissance symbol of perfect masculine beauty. The relationship between David and Jonathan, ‘passing the love of women’, has suggested to many readers of the Scriptures a romantic liaison between two young men sworn to love and parted only by death.

The sex-obsessed Judaeo-Christian tradition has not been kind to homosexuals. The burning of Sodom and Gomorrah, as recorded in the Torah, provided the name for the unnameable sin, and a precedent for God’s punishment. In the New Testament St Paul condemned homosexuality as an abomination – a pronouncement followed by later Christian leaders, who damned homosexual acts and sentenced sodomites to repentance or hell, to rectification of their ways or searing punishments in this world and the world to come.

In light of the homophobia of many churches, gay Christians have frequently sought refuge with congregations that do not condemn their yearnings, such as the Catholic Dignity organization, the Metropolitan Community Church or the French group called David et Jonathan. They have also, in amongst the biblical prohibitions against homosexual acts, found some comfort in the story of David and Jonathan, and in the friendship of Ruth and Naomi (Ruth tenderly declared to her mother-in-law and best friend, ‘whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge’). In the New Testament, they find solace and inspiration in the intimacy between Jesus and his ‘beloved disciple’ – St John, who is often pictured nestling on Jesus’ breast at the Last Supper and as witness to his Crucifixion, where Christ confides his follower and his mother Mary to each other’s care. Although most biblical scholars and (it goes without saying) traditionalist clerics and scriptural commentators reject the notion of a physical relationship, or even intimacy, between these couples, their tales have often given succour to those who strive to reconcile sexual desires with spiritual beliefs.

What is known about the life of Sappho fills hardly a paragraph, and her surviving poems, many so fragmentary as to extend to only a few words, cover just thirty or forty pages. Yet she occupies a prominent place in history, as the woman who gave her name to what was called ‘sapphism’, and what today is called ‘lesbianism’, after the island of her birth. Well may she have written: ‘I think that someone will remember us in another time.’

The facts remain uncertain, but it seems that Sappho was born near the end of the 7th century BCE on Lesbos, in the eastern Aegean; her family was prosperous, though she was orphaned as a child. She lived for most of her life in Mytilene, the island’s principal centre, except for a period of exile in Sicily, probably occasioned by her family’s political activities, in Sicily. She was married and had a daughter. She had two brothers, and the romantic affair of one of them, who was swindled by a prostitute, troubled her. Legend has embroidered various other details to her biography – that she was unattractive; that she was the head of a school for girls; that she hurled herself off the Leucadian cliff into the sea, suffering unrequited love for a handsome boatman called Phaon – but very little is really known. The suicide, possibly a tardy addition to the Sappho legend, conveniently served those who wished to deny her lesbianism and to suggest that she was a closet heterosexual.

Sappho’s poems, even in the truncated form in which they have come down through the ages, speak beautifully of yearning, love, heartbreak and the sensual delights of the Mediterranean. Invocations of the deities remind present-day readers of a classical religion in which the gods could be summoned to bless rather than damn same-sex affections. Images of ambrosia and goblets of wine, the fragrance of myrrh and frankincense, the sound of flutes and lyres, garlands of roses and crocus – even if they were moderately regular accoutrements of daily life in ancient Greece – are romantically evocative.

The poet loved the beauty of young women – ‘towards you beautiful girls my thoughts / never alter’, she writes in one fragment. She fell in love, and one poem intimates the sexual consummation of her desires. She vividly describes the spine-tingling, sweating, ear-throbbing physical effects of passion. Love also brought pain, and in one of the more complete poems to survive Sappho voices distress that a lover is now drawn to someone else, a man. Elsewhere she addresses a girl several times by name, though with the melancholy of an affair that has come to an end: ‘I was in love with you, Atthis, once, long ago’. She calls upon Aphrodite to bring comfort in her lovelorn solitude and to revive a friend’s affections. She writes about a wedding, congratulating a bridegroom on his beautiful spouse. Writing as an ageing woman, the poet recalls threading love garlands; she realizes that certain sorts of love have now slipped away, yet mischievously reminds those still in the throes of passion that ‘we, too, did such things in our youth’. And she tenderly expresses a hope for her readers in a single-line fragment: ‘May you sleep upon your gentle companion’s breast.’

Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Sappho and Alcaeus, 1881 (Walters Art Museum, Baltimore)

Much of our limited knowledge about lesbianism in ancient Greece comes, as the historian Leila Rupp has reminded readers, from a few suggestive images on vases and from the random, sometimes disobliging comments of men often found in Greek comedies. The sexuality of women was of little public import, except where it concerned the pleasures and familial obligations of men, and sex without phallic penetration barely counted as sex at all. Women did not show off their bodies in homosocial settings, as men did in the gymnasiums, and philosophers seldom ennobled passionate feelings between women with the same educative or philosophical mission as that accorded to intercourse between noble men and youths. There is some indication from Plutarch, however, that maidens and older women in Sparta entered into lasting relationships. In one of Lucian’s dialogues, a young woman, Leaena, recounts a Sapphic symposium where, after appropriate music-making, she was initiated into a sex triangle with a pair of partnered women, Demonassa and Megilla, the latter of whom happened to hail from Lesbos and took pride in her manliness as she moved to embrace her. For the classical scholar James Davidson, the mise en scène implies not only lesbian seduction, but the existence of declared lesbian couples in archaic Greece.

The relative silence about female same-sex love makes Sappho’s voice particularly resonant. The shards of her verses offer the first clear expressions of love between women in classical European literature and some of the most tantalizing literary images of lesbianism in the legacy of antiquity. Yet the sentiments painted in her verses are universal. It is no surprise that Sappho has been regularly rediscovered – a lesbian circle in early 20th-century Paris grew so enamoured of the poet that they occasionally dressed in ancient garb and recited her verses in Arcadian gardens, even making a pilgrimage to Lesbos. In the context of the women’s movement of the 1960s, Sidney Abbott and Barbara Love wrote a ‘liberated view of lesbianism’ entitled Sappho Was a Right-On Woman. As the classicist Alastair Blanshard has shown, Sappho, like other figures of antiquity connected with love and lust, has become a ‘brand’, omnipresent in literature and imagery.

Sappho’s image appears in many fanciful manifestations. The rather lifeless statue of her in Mytilene, shouldering a lyre, bespeaks pride in the island’s native daughter but also discomfort with her sexuality. Indeed, in 2008 the good people of Lesbos mounted a court case, unsuccessfully, to try to ensure that the term ‘lesbian’ applied only to the residents of the island, not to sapphists. Other statues turn Sappho into an alluring naked seductress, though probably many were meant to lure men rather than women. In other incarnations, she has become a leisured beauty, a stern Victorian bluestocking, a winsome adolescent, an ethereally pastel spirit ascending to the heavens, and a brooding, bare-breasted bard cloaked in mysterious black. The metamorphoses are further proof of Sappho’s endurance as honoured poet and lesbian icon.

‘Greek love’ has long been a synonym or euphemism for homosexuality, especially for relations between two males. Much depends on the eye of the beholder, however. Voltaire commented that ‘if the love that is called Socratic or Platonic was a virtuous sentiment, then it must be applauded, but if it was debauchery, then one must blush in shame for Greece.’ For generations of homosexuals – as illustrated by Oscar Wilde’s testimony that love between an older and a younger man, of which he himself was accused, served as the basis of ancient philosophy – the Greek paradigm provided an ennobling model for reprobate desires. Since classical Athens was one of the high points of civilization (so the argument ran), Greek same-sex practices could hardly be ignoble.

Homosexual practices in ancient Greek culture are visible in many forms – figured on vase paintings, described in literature, recorded in history and theorized in philosophy. Those familiar with the Classics (which, until recent times, included most of the Western educated elite) noticed the blatant images of seduction and copulation in Greek art. They knew of the cult of erotic male beauty, developed and displayed by naked athletes on exercise grounds and at athletic contests. They learned of famous male couples in antiquity – Achilles and Patroclus, Harmodius and Aristogeiton, Alexander and Hephaestion – and could retell the feats of the Sacred Band of Thebes, where love between warrior partners steeled their courage. They knew that gods, as well as men, overflowed with homosexual passion, Zeus himself descending to earth to seize the beautiful Ganymede as his cupbearer and lover.

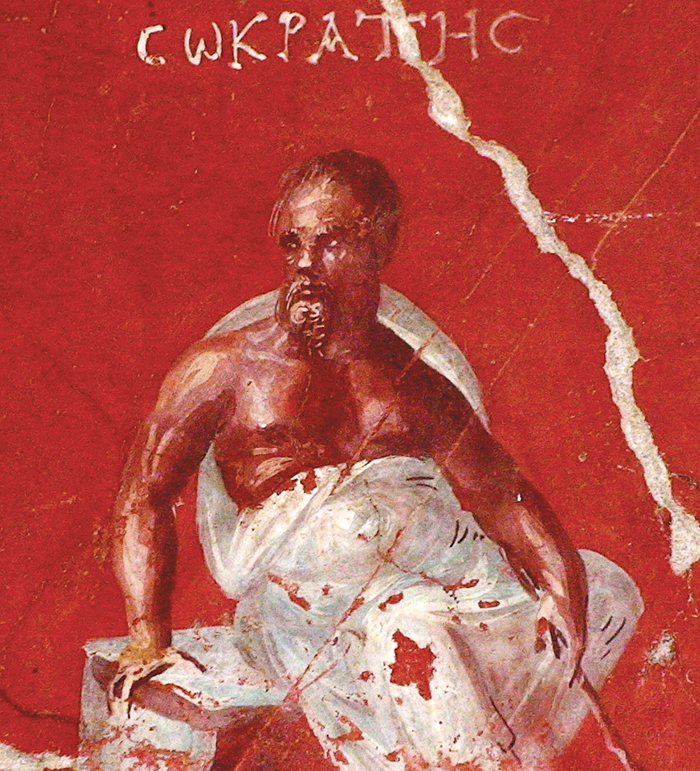

For students of antiquity (especially those who could access unbowdlerized translations), the dialogues of Plato held a special place. The star of these dialogues was, of course, Socrates, Plato’s mentor and one of the most influential of Greek philosophers. Socrates was a 5th-century Athenian who did not write down his words, and biographical information is scarce (the figure who appears in Plato’s dialogues is unlikely to be an exact reflection of the real man). He may have been the son of a stonemason and his midwife spouse; scholars are more certain that he performed military service as a heavy-armed infantryman. He married a certain Xanthippe, about whom he was rather critical, and fathered several children. In time he came to dedicate his life to teaching, using the so-called ‘Socratic method’ to cross-question his students; the resulting dialogues are those recorded by Plato. He eventually incurred the wrath of the city authorities, however, and was arrested on the charge of corrupting the minds of youths and introducing strange gods. In 399 BCE he was condemned to kill himself by drinking hemlock.

Like most men in Athenian society, Socrates would no doubt have had sexual liaisons with young men, and even in old age was said to chase boys. Athenian mores not only tolerated but applauded emotional and sexual intercourse between men, though with certain caveats. In principle this form of sex, known as paiderastia, should occur between an adult man and an ephebe, or adolescent from a suitable social class; the older lover (the erastes) was meant to play the active role, his partner (the eromenos) the passive one, in anal or intercrural sex. The relationship was also ideally one in which the adult oversaw the education and upbringing of his younger friend. When he became an adult, the ephebe would in turn take younger partners of his own. Greek men were expected to marry and to father children, though this did not oblige them to abandon pederastic pursuits.

Roman fresco of Socrates from Ephesus, 1st century CE (Ephesus Museum, Selcuk)

There has been intense scholarly discussion on the subject of Greek sexuality. David Halperin, for instance, accentuates the penetrative side of sex, emphasizing the unequal nature of the relationship between older and younger men, and its wider context of asymmetrical social relations. James Davidson, however, convincingly finds a much more varied experience of homosexual love and sex in Greece, and focuses on the romantic, emotional and cultural aspects of the relationships rather than the phallic ones. The Greeks, indeed, displayed an intense form of male bonding and male-to-male attraction that was not simply orgasmic – what Davidson playfully refers to as ‘homobesottedness’.

Socrates obviously liked young men. One of them was Charmides, who was Plato’s uncle and later took part in an oligarchical revolution. The meeting between the philosopher and Charmides, then an irresistible ephebe, is recounted in the dialogue that bears his name. Socrates swoons when Charmides arrives at the palaestra, or training ground: ‘I was quite astonished at his beauty and stature; all the world seemed to be enamoured of him … and a troop of lovers followed him.’ After some unseemly jostling to sit near the young man, Socrates continues: ‘I saw inside his cloak and caught on fire and was quite beside myself. And it seemed to me that Cydias was the wisest love-poet when he gave someone advice on the subject of beautiful boys and said that “the fawn should beware lest, while taking a look at the lion, he should provide part of the lion’s dinner”, because I felt as if I had been snapped up by such a creature.’ Alastair Blanshard, a scholar of sexuality in the ancient world, comments that the sexual frisson of the anecdote has a very contemporary feel. It illustrates well that Socrates’ interests in youth were not purely, as it were, platonic.

In the Symposium, Socrates and his interlocutors discuss love – indeed, the work provides Western literature’s classic discourse on the topic. Towards its end, the drinking party and debate are interrupted by the arrival of a merrily inebriated Alcibiades. A local celebrity – aristocratic in parentage, heroic in battle, and a would-be student of philosophy – Alcibiades was the very incarnation of masculine strength and beauty. There is some good-natured verbal jousting between Alcibiades and Socrates, with Alcibiades lamenting that he, handsomest of men, has been unable to seduce Socrates, wisest of the pedagogues. Brains do seem to be winning over brawn when Socrates expostulates the theory of love given to him by a wise woman named Diotima; but her argument, it transpires, is that love of the beautiful object can lead to love of transcendent beauty, a means of moving from the physical to the ideal. It goes without saying that the beloved object showing the way is a handsome youth.

The Platonic, and Greek, concepts of love between men cannot be summed up easily, for, in good philosophical fashion, there was much debate. But Socrates’ legacy is enormous. His Athenian vision of beauty, as exemplified by Charmides and Alcibiades, established a standard for the Western world, sculpted in Greek statues and the Neoclassical works they inspired: the slender, finely muscled, beautiful-faced young man. Another Platonic dialogue, the Phaedrus, offers not only the picture of a teacher and his student happily conversing on love, but also the vision of a charioteer – a metaphor for the soul – trying to control his horses, which represent spiritual and carnal urges. To latter-day homosexuals, the erotic milieu in which Socrates lived seemed a type of paradise: celebration of the appeal of ephebes; open seduction and unashamed intercourse between males; a link between manliness and same-sex sex; and examples of heroic male bonding. Plato’s explanation that the search for love is a search for one’s ‘other half’ – and that the cloven halves may be male and female, or of the same sex – was taken up by 19th-century theorists who saw homosexuals as a ‘third sex’. Socrates’ evocation of earthly passions as a way to reach divine enlightenment turns pederasty into philosophy.

Hadrian 76–138 CE and Antinous c. 110–130 CE

Of all the love stories between men in history, that of Hadrian and Antinous is among the most poignant: the relationship between a Roman emperor, the most powerful ruler in the world, and the handsome young man who drowned in the Nile and was made into a god by his grieving lover.

Hadrian was one of the greatest emperors of Rome. He secured the empire when it had reached its widest extent, from Scotland, where his famous wall was erected, to the Sahara, and from the Atlantic to the Euphrates. He prided himself on having ruled without a single war of aggression, unlike his predecessors. He reorganized the empire’s administrative, financial and military system; his law code endured for four hundred years; and among his most impressive monuments are the rebuilt Pantheon in Rome, a grand villa at Tivoli and, as his mausoleum, the structure now known as the Castel Sant’Angelo.

Bust of Hadrian in military dress, c. 125–130 CE (British Museum, London)

Historians know little about Antinous. He was probably born around 110 CE in Bithynium (also called Claudopolis), a town in the fairly remote Roman province of Bithynia, now part of Turkey. Antinous, like many residents of the eastern empire, was of Greek genealogy and culture, though perhaps with some admixture of Levantine ancestry. Images show a young man with a strong chest and shoulders, curly hair, a roundish face with sensual lips, and overall startling beauty. Hadrian may have met him while touring the East in 123, but that is uncertain, as are the circumstances in which Antinous went to Rome, though he may initially have been a page at the imperial court. In any case, Hadrian fell in love with the ephebe. A set of bas reliefs suggests that they hunted together (hunting was the emperor’s favourite sport), and Antinous may have been initiated into the esoteric Eleusinian mysteries when he travelled with Hadrian to Athens.

The same voyage took Hadrian and his retinue from Greece to Asia Minor, Palestine and on to Egypt, where it ended tragically. After visiting Alexandria, the imperial group sailed down the Nile, where Antinous died in mysterious circumstances. It could simply have been a terrible accident, but one suggestion is that Antinous committed suicide on the anniversary of the death of the god Osiris, sacrificing himself after reports of dire auguries, in order to propitiate the gods of the Nile, prolong the emperor’s life and assure his good fortune. Over the course of the centuries, there have also been suggestions that it was a rival for the emperor’s favour who had Antinous killed, or even that Hadrian himself had sacrificed Antinous – according to one gruesome interpretation, so that he could divine the future from his victim’s entrails.

Onyx gem featuring a portrait of Antinous, 2nd century CE (Beazley Archive, University of Oxford)

On the death of his beloved, Hadrian (in the words of a Roman historian writing a century later) ‘lamented him like a woman’. The emperor made the small town where Antinous died, Besa, into a new city named Antinoöpolis, complete with a theatre, gymnasium and the other constructions of a Roman metropolis. He proclaimed Antinous a god and promoted his worship with the building of temples. Yearly athletic contests were held in his memory. The emperor had coins minted and medals struck with the image of his friend, and statues of Antinous graced cities around the empire. At Tivoli, Hadrian erected a shrine, and for an obelisk – which perhaps stood first in Antinoöpolis, then was moved to Tivoli, and now can be found in Rome’s Pincio Gardens – he composed an epitaph, engraved in hieroglyphics, to ‘Osiris Antinous, the just, [who] grew to a youth with a beautiful countenance, on whom the eyes rejoiced’. A new star was declared to be the soul of Antinous flown to the heavens, and a new variety of lotus was said to have bloomed at the moment of his death.

Homosexual relations were not uncommon in the Roman Empire, generally between an older (and free) man and a younger man (or slave), with the convention that the senior partner must play the active role in sexual intercourse. Antinous was apparently not the first of Hadrian’s male partners, though Hadrian was also married, but the intensity and longevity of their relationship was remarkable. Roman history offers no other example of the deification of a male lover.

The cult of Antinous spread widely within the empire, perhaps aided by the desire of Greeks to secure the emperor’s good graces in honouring their kinsman. For more than two hundred years Antinous was worshipped widely, but in time another god arrived to challenge his popularity. By the late 300s images of the crucified Christ had displaced those of the comely Greek in houses of worship.

Christian commentators, not surprisingly, condemned the worship of Antinous and the sinful relationship that it commemorated, St Athanasius writing about ‘Hadrian’s minion and slave of his unlawful pleasures’, the ‘loathsome instrument of his master’s lust’. Later generations responded differently to the emperor and his beloved, especially as the wonderful statues, busts, coins and jewels decorated with his features came to light. Indeed, Antinous is one of the most depicted figures of antiquity – as boyish or virile, as the Egyptian Osiris or the Greek god Dionysus, and in many other guises. In the 1700s Johann Joachim Winckelmann, a noted Neoclassicist, the father of art history and a homosexual, described the Mondragone head of Antinous (a sculpture now in the Louvre) as ‘the glory and crown of art in this age as in all others’.

For Winckelmann and for others like him, the beautiful Antinous, and the partnership between the Bithynian boy and the Roman emperor, exerted a special fascination. John Addington Symonds’ Sketches and Studies in Italy and Greece, published in the 1870s, included a learned and evocative essay on Antinous and the enigma of his death. Symonds’s view was that ‘Hadrian had loved Antinous with a Greek passion’, and he compared the couple to Zeus and Ganymede, Achilles and Patroclus, and Alexander and Hephaestion. He likened Antinous also to St Sebastian, the early Christian whose body pierced with arrows became both a religious and a gay symbol: ‘Both were saints: the one of decadent Paganism, the other of mythologising Christianity. According to the popular beliefs to which they owed their canonisation, both suffered death in the bloom of earliest manhood for the faith that burned in them.’ In 1915, a long poem by the gay Portuguese Fernando Pessoa painted a picture of the bereaved emperor and the communion of moderns with ancients: ‘His love is on a universal stage. / A thousand unborn eyes weep with his misery.’ In words of poetic power put into the mouth of the emperor, Marguerite Yourcenar’s 1951 novel Mémoires d’Hadrien recreates the golden age of Hadrian and Antinous’ union.

An exhibition held at the Henry Moore Museum in Leeds in 2006 focused on ‘Antinous: The Face of the Antique’, and a highly successful show on Hadrian at the British Museum, London, boasted a catalogue essay that began, straightforwardly, ‘Hadrian was gay’. Both provided a new perspective on the place of Antinous in the life of the emperor, and on representations of the young man in art.

In the West, homosexuals looked back to real-life or mythological figures from Greco-Roman times for examples of same-sex love. In imperial China, where homoerotic relations continued to flourish without European constraints, men and women also referred to famous individuals of ancient times, honoured rulers and ancestors who engaged in same-sex practices and loves.

Chen Weisong was not the earliest homosexual figure of repute in China, but verses telling the story of this renowned 17th-century poet use classical figures to celebrate his relationship with a young man – the young man who also forms the subject of Chen’s own poems. Chen was born in Yixing (in the present-day Jiangsu province) and completed the arduous examinations to enter the imperial civil service, winning appointment under Emperor Kangxi. One of his major professional accomplishments as a mandarin was to compile a history of the Ming dynasty. Chen also composed 1,600 poems in the ci style, which uses a set pattern of characters and tones; he wrote about the common people, national affairs and his feelings of desire.

Chen’s great love and life companion was Xu Ziyun (1644–1675), nicknamed ‘Purple Clouds’, who earned a reputation as the most alluring actor of his age. They met in a garden in 1658, when Chen was 35 years old and Purple Clouds, then still a pageboy, was almost 15. It seems to have been love at first sight, and thereafter they lived together as a couple within Chen’s entourage (which included a wife, two concubines and several children).

Many of Chen’s poems are about his lover. Purple Clouds’ departure on a trip to visit his parents inspired a suite of twenty ‘Lyrics of Wistful Bitterness’ in farewell to his friend, recalling their pleasures and bemoaning Chen’s empty bed and cold nights. Yet when they were reunited, he wrote happily about ‘my soulmate of this life’. He describes the handsomeness of the one whose ‘raven locks fall down his jade-white temples’, and joins his love for the youth’s beauty with his love of art. Artists, too, captured Purple Clouds’ image: what the sinologist Wu Cuncun considers the best picture shows him sitting on a rock, a flute close to hand, his long hair coiled in a knot, and a touch of rouge on his face, which wears an indolent and contemplative expression.

Chen helped Purple Clouds set up his own family; although he appeared somewhat jealous of the young man’s spouse, the relationship between the men did not alter. When Chen was transferred to an administrative post in Henan province, Purple Clouds followed him. When Purple Clouds died, after seventeen years of companionship, Chen mourned him inconsolably and continued writing poems memorializing his lover.

Fellow poets honoured the relationship between Purple Clouds and Chen Weisong. Wu Cuncun quotes from a work by Wu Qing, who contributed to an anthology of poems compiled in honour of Purple Clouds. It reads in part:

After playing a tune on the pipe,

Purple-Clouds’ cheeks flush.

Pretending musical appreciation,

Amorous glances fly between them.

Keeping intimate company over all these years.

Every morning and every night their souls firmly embraced,

A spell of love invaded Chen’s romantic verse.

Never believing a home could not be made by male-love,

Dreaming of a pillow shared in the fairyland.

Nothing of ‘the cut sleeve’ or ‘shared peach’ has been missed …

The last line establishes a connection between Chen and his lover and the most famous figures of ancient Chinese homosexuality. The reference to the ‘shared peach’ derives from an anecdote about Duke Ling of Wei (534–492 BCE), a provincial ruler and contemporary of Confucius. A young courtier, Mizi Xia, won his favour. According to an often cited source, one day ‘Mizi Xia was strolling with the ruler in an orchard and, biting into a peach and finding it sweet, he stopped eating and gave the remaining half to the ruler to enjoy. “How sincere is your love for me!” exclaimed the ruler. “You forgot your own appetite and think only of giving me good things to eat!”’ Although the ruler’s passions eventually cooled, Mizi Xia’s name became closely associated with homosexuality.

Scholars of the Northern Qi dynasty, silk handscroll, 11th century (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

A male couple with two dogs, 19th-century silk painting (Collection F. M. Bertholet, Amsterdam)

The second famous classical story, that of ‘the cut sleeve’, also comes from the imperial court, and illustrates the fondness of the Han emperor Ai (27–1 BCE) for Dong Xian. According to Brett Hinsch, who has written a study of homosexuality in China, one short passage about their love ‘is the most influential in the Chinese homosexual tradition: “Emperor Ai was sleeping in the daytime with Dong Xian stretched out across his sleeve. When the emperor wanted to get up, Dong Xian was still asleep. Because he did not want to disturb him, the emperor cut off his own sleeve and got up. His love and thoughtfulness went this far!”’

The ‘passion of the shared peach’ and the ‘passion of the cut sleeve’ thus became bywords for the homosexual behaviour that was commonplace in ancient China. At least ten emperors of the ancient Han dynasty openly engaged in same-sex affairs, male brothels operated for centuries in Beijing and other cities, and male marriages were occasionally celebrated in the province of Fujian. Homoerotic poetry abounded, with the works of Ruan Ji, a 3rd-century poet and one of the most revered authors in the Chinese canon, among the best known. Many scholar–officials like Chen consorted openly with male partners, and jokes and caricatures poked fun at mandarins for losing their hearts to handsome youths.

Wu Cuncun has shown that male beauty and sexual favours were assets that could be traded for social advancement and preferment. Certain categories of men – actors, opera singers, retainers and disciples – were generally viewed as potential objects of homosexual desire. Homosexual liaisons, like those between men and women, entered into the Confucian pattern of relations between superiors and inferiors – fathers and children, rulers and subjects, elder and younger – on which Chinese ethics rested. Whether a man took a dominant or subordinate role (active or passive, in both sexual and social terms) was more important than the gender of his partner in structuring intimate relations. Chinese men were expected eventually to marry and to produce children, especially all-important male heirs, but such unions did not impede the keeping of female or male concubines or the enjoyment of more casual encounters. Indeed, to have a young male partner in the late Ming and early Qing periods, Wu adds, was a sign of success and social standing, and many literati considered homosexual behaviour a praiseworthy and romantic practice.

The great changes that overwhelmed China during the 19th century – the Opium Wars, foreign incursions and Westernization – began to break down old ideas and practices, although a major homoerotic novel was published in the late 1840s, and in 1860 the city of Tianjin was reputedly home to thirty-five male brothels with a total of eight hundred employees. Sun Yat-sen’s revolution of 1911 and Mao Zedong’s of 1949 dealt fatal blows to the sexual traditions of imperial China. Only in recent years has a new gay culture emerged, albeit in the face of opposition from a state ideology that continues to regard homosexuality as deviant. It is more Westernized than traditional, but nevertheless harks back to the affections of Chen and Purple Clouds, and further back to Ling, Ai and their beloveds.