FROM THE MIDDLE AGES TO THE ENLIGHTENMENT

Saints Sergius and Bacchus 4th CENTURY CE

In 1994, the year that his life was cut short by AIDS at the age of 47, the gay, Catholic historian John Boswell published Same-Sex Unions in Premodern Europe. Basing his work on fifty-odd Greek and Cyrillic manuscripts from the 6th to the 16th centuries, Boswell brought to light ceremonies devised by the Eastern Church for joining together two men, rites remarkably like those of a wedding. The two men came before a congregation, their right hands laid one on top of another on the Gospel book and sometimes entwined in the priest’s stole, their left hands holding candles or crosses. Prayers were offered, and they embraced each other and the celebrant, and circled the altar. Although there were often no vows or an exchange of rings, as in heterosexual weddings, Boswell pointed out that these two standard features of marriage did not become common until much later.

Boswell also identified pairs of men who, whether they took part in such ceremonies or not, typified same-sex unions in the early church. Sergius and Bacchus were prime examples of a Christian partnership. The two were officers in the army of a pagan Roman emperor in the 4th century. According to one hagiography, ‘being as one in their love for Christ, they were also undivided from each other in the army of the united, united not by the way of nature, but in the manner of faith’. Once their religious heresy was discovered, they were ordered to sacrifice to Jupiter. When they refused, they were ritually humiliated; the emperor ‘ordered their belts cut off, their tunics and all other military garb removed, the gold torcs taken from around their necks, and women’s clothing placed on them’. The men’s continued defence of their faith infuriated the emperor, who had them cast into chains and banished to a distant province.

Strengthened by the visit of an angel when they again refused to recant, Bacchus was flogged to death. Sergius, ‘deeply depressed and heartsick over the loss of Bacchus, wept and cried out, “No longer, brother and fellow soldier, will we chant together, ‘Behold, how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity.’ You have been unyoked from me and gone up to heaven, leaving me alone on earth, bereft, without comfort.”’ That night Bacchus, dressed in his military uniform, appeared in a vision to Sergius, saying, ‘Why do you grieve and mourn, brother? If I have been taken from you in body, I am still with you in the bond of union.’ Once again refusing to deny Christ, Sergius was tortured and beheaded. Posthumously, the two men, ‘like stars shining joyously over the earth’, became the objects of a cult. For their unflagging faith, and for the miracles they performed, the church canonized them, and their friendship was lauded in stories about the lives of the saints.

Were the saints a gay couple, and were there same-sex unions in early European history? In recent years debate has raged in Western countries about ‘gay marriage’, a broad phrase encompassing arrangements from civil registration of partnerships to legal recognition and the sacramental union of two individuals of the same sex. Gay men and lesbians now demand the same civil rights enjoyed by heterosexuals in partnerships, such as equal rights of inheritance. Many countries (Spain, Portugal, the United Kingdom, France and the Netherlands among them) recognize same-sex unions, in some cases with complete parity between homosexual and heterosexual ones, although elsewhere (the United States provides an example) acceptance is conceded only by a few local governments, and in still other countries recognition is barely conceivable.

In addition to the state’s legitimization, some religiously inclined homosexuals yearn for religious benediction for their relationships. Religious groups other than the more liberal Protestant denominations, however, have refused to accept gay marriage. Clerics, indeed, have lobbied legislators to define marriage as the union of a man and a woman. In the words of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, a wedding ceremony serves ‘to join together this Man and this Woman in holy Matrimony; which is an honourable estate, instituted of God, signifying unto us the mystical union that is betwixt Christ and his Church’. A gay union, for conservatives, goes against the laws of God as well as the laws of nature.

It seems likely that Sergius and Bacchus did not exist in reality. The Greek-language Passion document that forms the basis of their story – its dating remains uncertain, but it was probably written a century or so after their supposed death dates, and was not translated into English until Boswell appended it to his volume – may have been a composite account of saintly lives and legends. Even if they actually did live, there is little evidence of romantic involvement, let alone that they had a sexual relationship, although Boswell adroitly drew on every shade of meaning to suggest an amorous partnership and church sanction for such a friendship. Churchly blessing of partnerships between men certainly existed, however, even if, as Boswell noted, it was mostly confined to the Eastern Church. These ceremonies of adelphopoiesis – ‘brother-making’ or ‘brotherment’ – may have been intended primarily to provide sanction for kinship unions or familial adoption.

Boswell’s book, not surprisingly, provoked much controversy, its conclusions welcomed by gay Christians but rejected by church leaders and many scholars. Further evidence of religiously blessed unions, of ‘brother-making’, has since been found in the Latin Catholic Church. Recent scholarship, in fact, has tended to give more credence to Boswell’s interpretation, or at least to the possibility that these rites could in some instances consecrate romantic or sexual partnerships.

Sergius and Bacchus remain emblems, in the religious imagination, of friendship, Christian devotion and martyrdom; to homosexual believers, they can be venerated as gay saints. If one assumes that Sergius and Bacchus were ‘gay’ – and there is no reason always to assume that a couple of men was not – then they provide an interesting model.

Whatever their historical or mythical status, the renewed attention given to Sergius and Bacchus shows the persistence of a desire to identify gay ancestors and to prove that Christianity has not always been as intolerant of same-sex relationships as it would appear. The debates surrounding the publication of Boswell’s book, and the story of Sergius and Bacchus, underline the continued role of religion in structuring popular attitudes towards homosexuality and gay unions. The words of the brotherhood ceremonies discovered by Boswell, whatever the exact nature of the unions they hallowed, provide templates for expressions of dedication and loyalty that resonate with modern same-sex couples.

Aelred of Rievaulx c. 1110–1167

Medieval monasticism and homoerotic sentiments are not usually seen as conjoined, but a certain type of intimacy between men, including those in holy orders – chaste, in principle – was lauded by Christian writers. St Aelred of Rievaulx is the author of the major philosophical treatise about ‘spiritual friendship’. Born into a prosperous family in Northumberland around 1110, he was educated at the court of the king of Scotland and, in his mid-twenties, joined the reformist Cistercian order set up by St Bernard of Clairvaux. In 1147 he became abbot of its monastery in Rievaulx, Yorkshire.

In an early work, Aelred wrote of his close friendship with another monk, Simon, who had recently died, and in De spirituali amicitia he developed his ideas on friendship in the form of three dialogues. In the prologue, he refers enigmatically to a youthful time when ‘I gave my whole soul to affection and devoted myself to love amid the ways and vices with which that age is wont to be threatened’; now he understands true friendship, however, and wishes to share his thoughts with his disciples. His interlocutor for the first dialogue, ‘my beloved Ivo’, died before the second was composed. There, Aelred evokes Ivo’s ‘fond memory … his constant love and affection’ – one of several intimate friends Aelred recalls, and about whom the symposium participants express great interest. His companion for the second and third dialogues is named Walter; they are joined by Gratian, and Aelred jokes with Walter that Gratian ‘is more friendly to you than you thought’.

Aelred divides friendship into carnal, worldly and spiritual. ‘Carnal’ is not so much defined as physical, however, except by metaphor, since ‘the real beginning of carnal friendship proceeds from an affection which like a harlot directs its step after every passer-by’. It is a lightweight, promiscuous connection inferior to more noble forms of friendship. Worldly friendship is one that seeks advantage and thus has particular self-serving motives, but spiritual friendship aims higher. It is an ideal union between two beings, similar to the union between a believer and Christ. Indeed, Aelred writes that ‘man from being a friend of his fellow man becomes the friend of God’ – a progression from the terrestrial to the heavenly that recalls the Socratic notion of love for the physically beautiful leading to love for the ideals of Beauty, Goodness and Truth. For Aelred, ‘your friend is the companion of your soul, to whose spirit you join and attach yours, and so associate yourself that you wish to become one instead of two, since he is one to whom you entrust yourself as to another self, from whom you hide nothing, from whom you fear nothing.’ The spiritual friend is also someone to whom nothing, save a sinful act, must be denied; it is a partnership, based on careful selection and testing, that expresses itself through eternal loyalty and shared affection, ‘an inward pleasure that manifests itself exteriorly’.

Ivory panel of a saint working in his scriptorium, 10th century (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Aelred’s dialogues allude to Cicero’s classical treatise De amicitia (‘On Friendship’) and to the Bible, including a couple of extended references to the exemplary friendship that existed between David and Jonathan. It is noticeable that his portrayal of friendship seems to relate exclusively to men: there is only one real reference to a link between a bride and a bridegroom, and an ordinary marital union is never compared to Aelred’s model of higher friendship. This is not surprising in the context of a monastic community, but nevertheless implies that his view of true friendship is a relationship achieved between men, not between the sexes.

Nothing in Aelred’s dialogues, to be sure, hints at sexual expression. His Christian beliefs would hardly have sanctioned such a suggestion, and neither would the politics of his time, when the sons and the grandson of William the Conqueror were damningly rumoured to be sodomites. Rather, Aelred is talking about a perfect, divine sort of friendship, which he concedes is rarely reachable. The form in which his ideas are voiced in fact describes what many – homosexual or heterosexual – might see as the perfect partnership between two people joined by matrimony or in a similar union. For most, however, his ideal is so pure and abstracted as to be not only near unobtainable, but also bloodless.

Other clerics gave voice in verse and letters to their desire for spiritual and occasionally for physical companionship. Marbod of Rennes, an early 12th-century French bishop, wrote poems about handsome boys, though he would seem, in such works as ‘An Argument against Copulation between People of Only One Sex’, to reject the physical expression of love for young men. Another, roughly contemporaneous French bishop in the so-called Loire School of poets, Baudri of Bourgueil, wrote more yearningly to one young friend: ‘If you wish to take up lodging with me, I will divide my heart and breast with you. I will share with you anything of mine that can be divided; if you command it, I will share my very soul.’ Whether such expressions are epistolary conventions, spiritual effusions or intimations of a carnal desire, repressed or consummated, may depend both on scholarly analysis and on the empathy of later readers. They remain touching panegyrics of what are, at least, especially close bonds of friendship between two men.

The amorous poems of Hilary the Englishman, who lived in the early 1100s as a canon at Ronceray in Angers, do not embed intimacy with young men in the usual spiritual coverings. ‘To a Boy of Angers’ includes such lines as, ‘I have thrown myself at your knees, / With my own knees bent, my hands joined; / As one of your suitors, / I use both tears and prayers’. In ‘To an English Boy’ he pays a particular compliment: ‘You are completely handsome; there is no flaw in you / Except this worthless decision to devote yourself to chastity’. Such lines suggest that the ethereal bonds praised by Aelred occasionally encompassed more earthly desires.

Michelangelo Buonarroti 1475–1564

Michelangelo was born into a society that lauded intimate friendships between men but punished sodomitical activities, a world in which present-day ideas of gender, sexuality and homosexuality did not apply. Neoplatonic humanism, which pervaded Renaissance life, viewed very highly the communion between men in which chaste love offered a pathway to discovery and appreciation of the good, the true and the beautiful. Affectionate affinity between men was a hallmark of learning and culture shared by philosophers, poets and artists. Church and state nevertheless condemned sodomy, punishing it with imprisonment or even execution. The city of Florence, where Michelangelo spent much of his life, had set up an ‘Office of the Night’ in 1432 to police sodomy. Nonetheless, a study by Michael Rocke, a historian of homosexuality in Renaissance Florence, has shown that the interdiction of same-sex activities between men seems to have been more honoured in the breach: some 17,000 men were investigated for sodomy between 1432 and 1502. As many as one in two Florentine men under the age of 30 came to the authorities’ attention in connection with the vice.

Manly love and sodomitical sex were thus both common in the Renaissance, and the borders between them were not always apparent. Michelangelo seems to have had few, if any, sexual relationships of a physical type, with either men or women. His emotional passion for Vittoria Colonna, a noblewoman, was an important episode in his life, but young men dominated as objects of his yearnings, foremost among them Tommaso de’ Cavalieri.

Michelangelo met the handsome Roman nobleman when he was 23, and the celebrated artist already in his late fifties. Cavalieri gave Michelangelo his friendship and affection, though without the same intensity that Michelangelo felt, and if Michelangelo craved physical consummation, Cavalieri seems to have withheld it.

Michelangelo was an accomplished poet, and his verses reveal details of their relationship. He was absolutely besotted with Cavalieri, ‘he who makes night of day / eclipsing the sun with his fair and charming features’; the poet devised a neat pun to say that ‘an armed cavalier’s prisoner I remain’. Cavalieri’s mere presence ignited a fire in Michelangelo, enchanted by a veritable obsession – ‘for whatever is not you is not my good’ – and he writes of ‘my sweet and longed-for lord’. There is a hint that such ardour violated canons of proper behaviour: ‘What I yearn for and learn from your fair face / is poorly understood by mortal minds’; and ‘the evil, cruel, and stupid rabble / point the finger at others for what they feel themselves’ – Michelangelo did indeed have to defend himself against rumours that he engaged in sodomy. Alluding to Neoplatonic Christian sentiment, he declared: ‘A violent burning for prodigious beauty / is not always a source of harsh and deadly sin, / if then the heart is left so melted by it / that a divine dart can penetrate it quickly’. Although Cavalieri’s reserved reciprocation brought pain, his intimacy also provided fulfilment: ‘I’m much dearer to myself that I used to be; since I’ve gotten you in my heart, I value myself more, / as a stone to which carving has been added / is worth more than its original rock.’

The art historian James Saslow has shown that Michelangelo put his love for Cavalieri into his art as well as his writing. A homoerotically coded image to which Renaissance artists often returned was the myth of Jupiter and Ganymede, in which the king of the gods swooped down from the heavens in the form of an eagle to capture a beautiful youth as his cup-bearer and lover. A series of drawings that Michelangelo made for Cavalieri picture the eagle and the young man in erotic detail. Cavalieri wrote to Michelangelo that the drawings gave him great pleasure, and they also won admiration from the cognoscenti. Saslow argues that the drawings were a philosophical gift exemplifying both Neoplatonic and Christian ideals, but they were also emblems of Michelangelo’s homoerotic passion and love for Cavalieri, the upward transport of joy with which he burned.

Michelangelo’s artwork (as is common for Renaissance Italians) is replete with handsome men, from muscular archers to a sensual dying slave. His monumental sculpture of David, completed in Florence in 1504, stands as one of the most dramatic and appealing images of a young man in the history of art, combining the ideal of classical male beauty with an allusion to the strength and courage of the ancient Israelite who was Jonathan’s beloved friend. It is not surprising that, by the 19th century, Michelangelo was seen, in the words of the art historian Lene Østermark-Johansen, as a ‘patron saint of sexual inversion’.

Nearly four decades after the David, Vatican officials were so scandalized by the nudity in Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, the fresco he painted for the Sistine Chapel in Rome, that they eventually hired another artist to paint in genital-hiding drapery. Recent research by Elena Lazzarini has suggested that Michelangelo’s models for the men who people the work were rugged manual workers he met during visits to Roman baths, which in addition to providing bathing facilities, massages and rudimentary medical care also served as places of male and female prostitution. In frequenting the rough workmen of Rome, pining with love for Cavalieri, and expressing his attraction for the male through the archetypes of pagan and Judaeo-Christian male beauty, Michelangelo represented much of the homoerotic culture of the Renaissance.

The dome of St Peter’s and the Pietà inside the basilica, the paintings of the Sistine Chapel, and the Medici Chapel and Laurentian Library in Florence are some of the works that made Michelangelo one of Europe’s greatest and most versatile cultural figures. He had an exceptionally long life, and Tommaso de’ Cavalieri – by then a married man and Michelangelo’s friend for over thirty years – was one of those at his bedside when he died.

‘If you ask me to say why I loved him, I feel that it can only be explained by saying: because it was him, because it was me,’ said Michel de Montaigne, simply but profoundly, to explain his friendship for Étienne de La Boétie. The two met at a ‘great crowded town festival’ in the late 1550s, though Montaigne was already familiar with La Boétie, born in 1530, from his reputation as a brilliant young writer. A few years his junior, Montaigne was the scion of a merchant family in Gascony who would become a councillor in the parlement of Bordeaux, the city’s mayor, and – with his Essays – one of the major literary figures of the French Renaissance. He and La Boétie immediately entered into a relationship that lasted for four years, until La Boétie’s death from the plague.

Montaigne’s essays range over topics as diverse as cannibals, old age, drunkenness, education, glory and thumbs. One of them, De l’amitié (1580), is generally known in English as ‘On Friendship’, although the editor of one version (for Penguin Classics) renders the title as ‘On Affectionate Relationships’, thus underlining the particular nature of the friendship on which the work focuses. Montaigne reviews various types of friendship, all of which seem limited, save one. That between father and son is constrained by parental obligations and respect. Love between brothers may be muddled by the clash of different characters or by varying trajectories in life. Love for a woman finds its expression in the passing ‘flames of passion’, and Montaigne, sharing the views of many of his time, doubts that any woman can really contract the ‘holy bond of friendship’ that offers a true meeting of minds and is thus the province of men. He then discusses Greek love. Though he characterizes paiderastia, the love practised by the Ancients, as ‘rightly abhorrent to our manners’, Montaigne’s real concern is the disequilibrium that exists in a partnership between men of different ages and with different levels of experience. He concedes, however, that in its best examples Greek love could lead to an initiation into philosophy, respect for religion and loyalty to the state. He adds that such unions could indeed be good, and he quotes Cicero: ‘Love is the striving to establish friendship on the external signs of beauty.’

Montaigne then turns to consideration of the ideal type of love, represented as that between La Boétie and himself: ‘In the friendship which I am talking about, souls are mingled out and confounded in so universal a blending that they efface the seam which joins them together so that it cannot be found.’ This is a selfless friendship, one man ready to give all for his friend, everything ‘genuinely common to them both’, an exclusive friendship so strong that it cannot be replicated or divided with other acquaintances: ‘One single example of it is moreover the rarest thing in the world.’ Thus Montaigne mourned the loss of his own friend, with no consolation possible.

‘It is not my concern to tell the world how to behave (plenty of others do that)’, Montaigne declares; but he slyly mentions that, ‘in my bed, beauty comes before virtue’. In fact, he was married and the father of several children, and nothing suggests that he had a sexual relationship with La Boétie – that he was, in the description of his age, a ‘sodomite’. Such physical congress would perhaps have been ‘abhorrent’ – a sin in the eyes of a Catholic – but also a heinous crime that could have incurred execution. However, one should not assume that an ‘affectionate friendship’ such as Montaigne professed for La Boétie excluded some erotic component.

In the law codes of many countries (in Britain until the 19th century, for instance), conviction for sodomy required that prosecutors prove penetration by one man of another and ejaculation, an awkward piece of evidence to procure. This demand has continued to weigh the argument about homosexuality in the past on lust rather than love, and some writers still insist on finding stains on the sheets: men are guilty of heterosexuality unless it is proved otherwise.

George Haggerty, in a study of friendship in early modern Europe, has suggested another approach that might have won sympathy from Montaigne: refusing distinctions between genital and emotional relations ‘to rewrite our understanding of male–male desire, not only in terms of sodomy and sodomitical relations but also in terms of love’. In examining masculinity and heroic friendships, among other sorts of bonding in the 17th and 18th centuries, Haggerty intimates that love between men was commonplace and immensely strong, and that such emotional attachments are actually more threatening to conventional society than sodomitical acts: ‘Two men having sex threatens no one. Two men in love: that begins to threaten the very foundations of heterosexist culture.’

Haggerty’s work on Men in Love finds company with other scholarly treatments of masculine unions, notably Alan Bray’s The Friend, which also stresses the importance of bonds between men in early modern Europe, emotionally intense relationships not devoid of physical expressiveness and an erotic charge. Fond comradeship, intellectual collaboration, warm correspondence, and occasionally joint burial in the same tomb provided expressions of such friendships as those vaunted in Montaigne’s writings and symbolized by his affection for La Boétie.

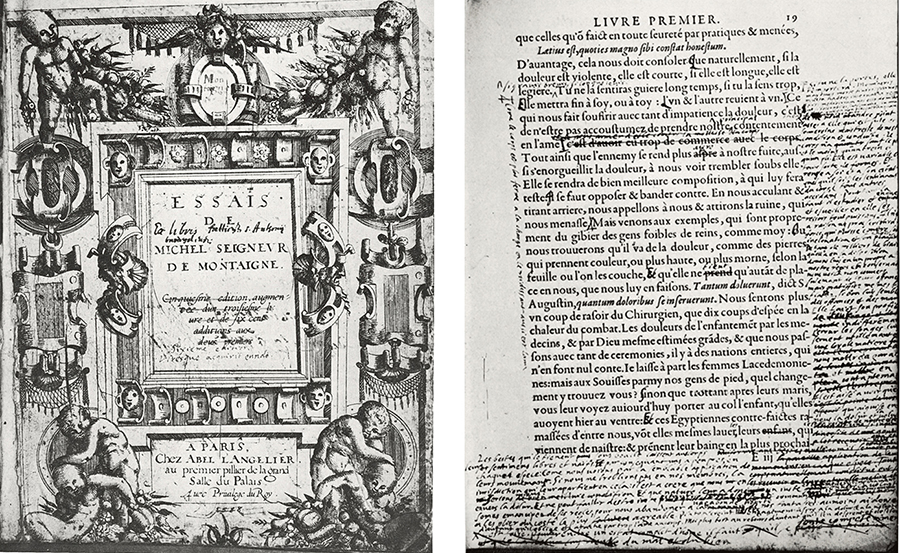

Two pages from Michel de Montaigne’s Essais, with the author’s handwritten corrections (Bibliothèque Municipale, Bordeaux)

Antonio Rocco, born in the Abruzzo region of Italy, studied in Padua, Perugia and Rome, and became a friar in Venice, where he lived the rest of his life. He taught philosophy and rhetoric, and published various learned treatises, especially on Aristotelian thought. He also participated in one of the Venetian Republic’s major cultural institutions, the Accademia degli Incogniti, whose members were known for their free-thinking views.

Rocco was identified in the 1800s as the author of L’Alcibiade fanciullo a scola (‘Alcibiades the Schoolboy’) – perhaps the most extraordinary dissertation on homosexuality in early modern Europe. Written in 1630 and tentatively published in 1651, it attracted immediate condemnation from the Church, and all but ten or twelve copies of the second edition were destroyed (no copies remain of the first edition). The work resurfaced in a French translation in 1862, only to be banned, then was reissued in Brussels four years later. It was quoted by the homosexual emancipationist and sexologist Karl Heinrich Ulrichs and the explorer Richard Burton, but has never been fully translated into English.

Rocco’s work is a dialogue between a teacher, Philotimos, and a student whom he is trying to seduce, Alcibiades – the name of the youth alluding to Socrates’ pupil. Scholars have debated the work’s purpose, asking whether it was a parody, satire, a ‘carnivalesque’ book written for entertainment, an exercise in libertinism and pornography, an exposé, a metaphorical and coded mise en scène about the teaching and learning of rhetoric, or a serious discussion and defence of homosexuality.

Alcibiades the Schoolboy opens with a long and detailed description of the beauty of the young man, who is pictured as perfect in almost every sense. Alcibiades’ only fault is that, although he gives in to caressing and kissing, he will not consent to the ultimate act of intercourse so desired by his teacher. Philotimos proceeds to provide a convincing argument of why his pupil should relent. He wittily demolishes the idea that sodomy is unnatural; he explains that God punished the wicked cities of Sodom and Gomorrah not for sex but for other crimes; he calls upon historical and mythological examples to show that homosexual sex has won the favour of gods and great men. Taking a misogynistic tack, he demonstrates how male-to-male intercourse is superior to coitus with women. Examples from other cultures show that sodomy is widespread in civilization. Philotimos uses gastronomic metaphors to vaunt the gourmandise of gay sex. He promises the young man that he will experience great pleasure, and – in another wickedly devious approach – says that semen deposited in the anus goes straight to the brain, so sodomy is an ideal method of tuition. Finally the youth drops his robe, and the book concludes with a full-blown description of the student’s felicitous lesson in oral and anal intercourse.

The tale of winning Alcibiades’ mind and body provides at once a philosophical tale and an example of erotic literature. The genres of erotic literature and pornography – variations on the same theme – play an important part in the history of writing and in the lives of many people. Despite frequently being censored and censured by public authorities and moralists, homosexual erotic literature has always circulated among connoisseurs, albeit often covertly, under ‘brown-paper wrappers’ and earlier disguises. In the 18th century the Marquis de Sade and his compatriot Restif de la Bretonne penned erotic works portraying a formidable variety of sexual scenarios. The 19th and early 20th centuries proved more puritanical, but erotic literature continued to be passed around by cognoscenti and kept under close surveillance in the special collections of libraries.

Only with gay liberation – and the liberation of publishing about homosexuality – did some works come out of the secret libraries. An example from Victorian England is Teleny, or the Reverse of the Medal, written around 1890 (and occasionally attributed to Oscar Wilde), which tells the story of a convoluted but sexually intense affair between a Frenchman and a Hungarian. A French parallel is the 1911 novella Pédérastie passive: Mémoires d’un enculé (‘Passive Pederasty: The Memoirs of a Buggered Man’), like the Alcibiade a mixture of philosophy and pornography. The more scabrous passages in Rocco’s little book are the ancestors of such works and countless later erotic and ‘one-hand’ novels.

Rocco’s work also contributes to the body of theories surrounding homosexuality. Its dialogue form creates a link between Plato’s works and André Gide’s early 20th-century apologia for homosexuality, Corydon (1924). Like Gide, and such commentators on homosexuality as Edward Carpenter and Magnus Hirschfeld, Rocco as a philosopher of homosexuality is concerned with the historical antecedence of same-sex relations, the debate on whether they are natural or not (and whether they should be banned if contra naturam), and the question of pleasure. He boldly challenges scientists, priests and traditional educators. Moreover, Philotimos’ rhetoric suggests that a self-assumed homosexual identity, and not just the practice of engaging in sodomitical acts, already existed in the 17th century. Homosexuality was, in his view, natural for the construction of a healthy body and a healthy mind.

Antonio Rocco, as depicted in Jacopo Pecini’s Le glorie degli Incogniti, 1647 (Raimondo Biffi Collection)

Yet another theme – a delicate one – finds illustration in Alcibiade. Nowadays, Philotimos could be indicted, and probably convicted, for sexual abuse and for taking advantage of his pedagogical position (even if, ultimately, his pupil consented). Alcibiades’ age is unclear, but Philotimos might now be charged with paedophilia as well. However, before passing sentence on sexual crimes, readers and historians must place Rocco and Alcibiades into the context of a time when philosophically intimate relations between master and student were viewed liberally, and of a society with radically different notions of sexual maturity and legal majority. Indeed, even in present-day Italy the age of sexual consent is 14, rising to 16 if the older person holds some position of influence over the younger partner (as a teacher, for instance). Throughout much of history, as Germaine Greer has shown, the figure of the attractive ‘boy’ – mythological hero, young warrior, schoolboy, scion of an aristocratic family – has attracted artistic attention as the incarnation of beauty on the cusp of manhood. For some men and women, such ephebes also excited sexual desire.

Not enough is known about Rocco’s own life to discern whether he followed the practices of Philotimos. There is no record to suggest that he was prosecuted for sodomitical offences in Venice; archival documents record only that Rocco did not attend mass, lived as an atheist, and argued that the soul was not immortal and that infidels could be saved. Despite legislation outlawing the ‘crime against nature’, homosexual behaviour remained widespread in the most serene republic.

‘For two continuous years, two or three times a week, in the evening, after disrobing and going to bed waiting for her companion, who serves her, to disrobe also, she would force her into the bed and kissing her as if she were a man she would stir on top of her so much that both of them corrupted themselves because she held her sometimes for one, sometimes for two, sometimes for three hours … Benedetta, in order to have greater pleasure, put her face between the other’s breasts and kissed them, and wanted always to be thus on her.’

Thus did papal emissaries record the testimony of Bartolomea Crivelli, a nun who revealed her sexual relationship with another sister in 17th-century Italy. Judith C. Brown, who discovered the documents, has reconstructed the ‘life of a lesbian nun’ in the Renaissance.

Benedetta Carlini was born in 1590 to a prosperous family in the Apennine mountains near Florence. Because mother and child almost died at birth, she was promised to a religious life in fulfilment of a vow, and at the age of 9 joined a newly established convent of Theatine nuns in Pescia. She remained there until her death at the age of 71. The nuns led a contemplative life, spinning silk to pay the expenses of the community. Carlini earned a reputation for piety and, when the Convent of the Mother of God gained full monastic rights of enclosure from the Holy See, the congregation elected Carlini as abbess in 1620.

For several years Carlini had been having visions – not an uncommon occurrence for fervent Christians – in which she saw Jesus and the angels, and a statue of the Virgin Mary that bent over to kiss her. The visions became more intense and bizarre, and Carlini told others that handsome young men were pursuing and trying to kill her, and that she had visited a garden where a miraculous libation flowed from a fountain. She confessed that she had received the stigmata, the bleeding wounds of the crucified Christ. Falling into trances that lasted for hours, she saw Christ come down to tear out her heart, then return three days later to replace it in her chest with his own heart. When Christ appeared again in order to propose marriage, she convinced the nuns to decorate their chapel for the wedding, and she received a ring – which initially only she could see – from her Lord. She also suffered great pains and had difficulty sleeping, so a young nun – Crivelli – was instructed to share her cell and to comfort her during her spiritual and physical travails.

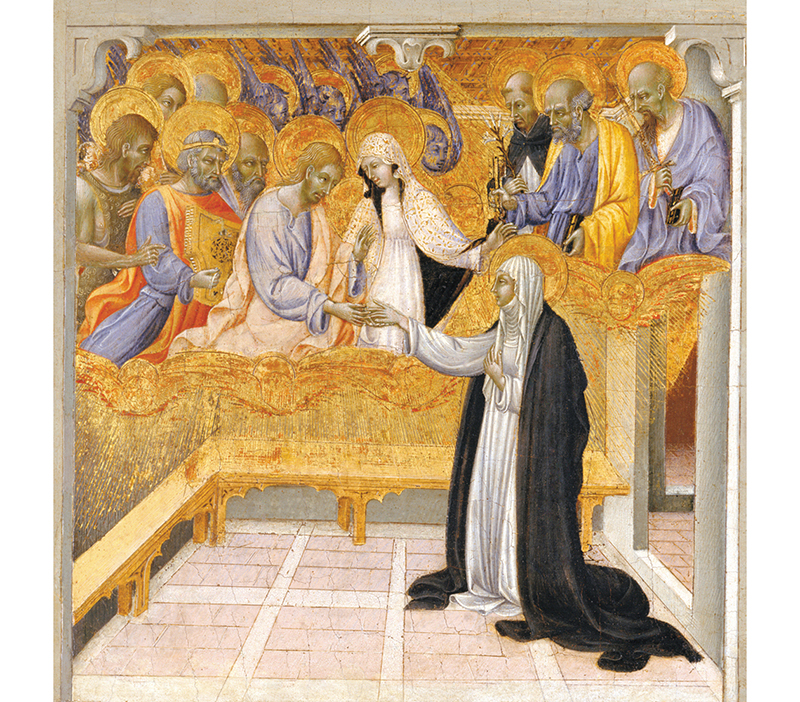

Saint Catherine of Siena has a vision, by Giovanni di Paolo, c. 1460 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Saint Catherine of Siena receives the Stigmata, by Domenico Beccafumi, c. 1513–15 (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

The nuns seemed to accept Carlini’s visions as real, and word of her mystical communion with God spread outside the convent. Clerical authorities, cautious about claims of visionary experiences and the stigmata, sent a priest to investigate. After fourteen visits, in which it seemed that Carlini indeed bore Christ’s wounds and that her visions were believable, he decided that she was genuine. Yet doubts persisted: there were contradictions (and signs of possible heresy) in her accounts of the visions, and concerns surrounded the nature of her stigmata. In 1623 officials launched another investigation, sending more inquisitive questioners from Rome. This time the priests decided that, instead of being possessed by God, Carlini suffered from demonic possession. The signs of her sanctity, moreover, were fraudulent: a star that she claimed had been bestowed by heaven was pasted onto her forehead, and the ring that had miraculously become visible was merely painted on her finger. The stigmata, too, were the result of self-inflicted wounds. The inquisitors also discovered Carlini’s relationship with Crivelli: kissing, caressing and mutual masturbation on a regular basis, by day and night. There was also a possible improper relationship with a priest.

For thirty-five years until her death, Carlini was confined in prison-like conditions in the convent. Crivelli died the year before the former abbess.

Carlini does not fit the role of a lesbian heroine. Her self-abuse and hallucinations indicate mental illness, and she exhibited predatory sexual approaches. (Although Crivelli may have been involved in a consensual relationship, she testified that she had been forced into sex.) Those who investigated Carlini were, of course, deeply shocked at her behaviour. It is impossible to say at the remove of several centuries whether Carlini’s lesbian desires were directly connected with her visions or even what they meant to her. She claimed that she had been possessed by a handsome young angel named Splenditello and had no memory of sexual relations with Crivelli, though her repeated sexual activities clearly gave physical pleasure.

Lesbians in the early modern world attracted less public concern than sodomitical men. Although convents were rumoured to be hotbeds of impropriety, most commonly this took the form of immoral assignations between priests and nuns. Theologians condemned all unholy sensual relationships, but jurists were unclear on legislation against sexual activities not involving men and phallic penetration. Lesbians generally came to attention mostly because of cross-dressing or refusal to adhere to expected standards of gendered behaviour. A situation in which relations between women constituted a peccatum mutum (‘silent sin’), according to the historian Edith Benkov, left opportunities in which intimacy might blossom.

Convents provided a refuge for women who wished to escape marriage and yet live respectably. Many nuns were literate, and a few extremely learned; and abbesses could become powerful figures. Convents often functioned simply as homes for unmarried women not necessarily called to a deeply pious life. They offered communities of women-only sociability. It is impossible to know how many nuns felt romantic affection or sexual desire for fellow sisters.

Historians have nevertheless discerned traces of lesbian relations, or at least intimate affinities between women, in monastic worlds long before Carlini. The 11th-century abbess, mystic, poet and composer Hildegard of Bingen, for instance, was much attached to another nun, Richardis of Stade. After ten years together, Richardis’ nomination to head her own abbey brought such distress to Hildegard that she sought to prevent the departure of the ‘deeply cherished’ Richardis, who ‘had bound herself to me in loving friendship in every way’ and whose leaving would ‘disturb my soul and draw bitter tears from my eyes and fill my heart with bitter wounds’. When Hildegard learned of Richardis’ death, she confided tenderly: ‘My soul had great confidence in her, though the world loved her beautiful looks and her prudence, while she lived in the body. But God loved her more. Thus God did not wish to give his beloved to a rival lover, that is, to the world.’ These fragmentary messages, a possible homoerotic reading of her poems, and Hildegard’s comment that a woman ‘may be moved to pleasure without the touch of a man’ suggest to the scholar Susan Schibanoff that love flourished between the women.

Hildegard and Richardis, and Carlini and Crivelli, joined in religious vocation but separated by half a millennium, illustrate different experiences of love and lust between women, a history of the ‘erased lesbian’ that is now becoming better known. That the convent continued to be a place where some women, happily or with difficulty, experienced lesbian yearnings is shown by the publication in 1985 of a volume of contemporary memoirs.

The life of Michael Sweerts would provide good material for a novel. He was born in Brussels, then under Habsburg rule, in 1618, at the beginning of the Thirty Years War. His father was a prosperous merchant in Flanders, a hub of international business. Sweerts was baptized a Catholic, but little more is known about him until he shows up in Rome around 1646, one of the northern artists who journeyed southwards to study the works of antiquity, enjoy Mediterranean culture, and paint. Although a loner, he established himself in the community of expatriate artists, and found in Pope Innocent X a patron. Sweerts stayed in Rome for almost a decade. He then appears in Brussels (though it is unclear why he returned to Flanders), where he set up a not entirely successful art school.

At the beginning of the 1660s, Sweerts unaccountably volunteered to join a missionary expedition to the Far East. The Paris-based Société des Missions Etrangères, under Bishop Pallu, recruited priests and lay people for a journey to Siam and China; among them were doctors, pharmacists and one painter. Three men would die in the Middle East, and two more in India, before the survivors arrived as one of the pioneering legations to the Siamese court in Ayutthaya. Sweerts helped supervise the building of the society’s ship in Amsterdam, then headed to Marseille, where the travellers set out for Palestine. In a letter to superiors, Bishop Pallu praised the Flemish artist’s piety, but along the way trouble occurred. Pallu revealed that Sweerts had become a busybody, meddling even in ecclesiastical affairs; he hinted that the artist had lost his mind. The conflict was resolved when Sweerts and the missionaries separated amicably, somewhere in Turkey or Persia. The artist moved further eastwards, making his way to the Portuguese colony of Goa, where he died in 1664.

Michael Sweerts, Self-Portrait as a Painter, c. 1656–60 (Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Ohio)

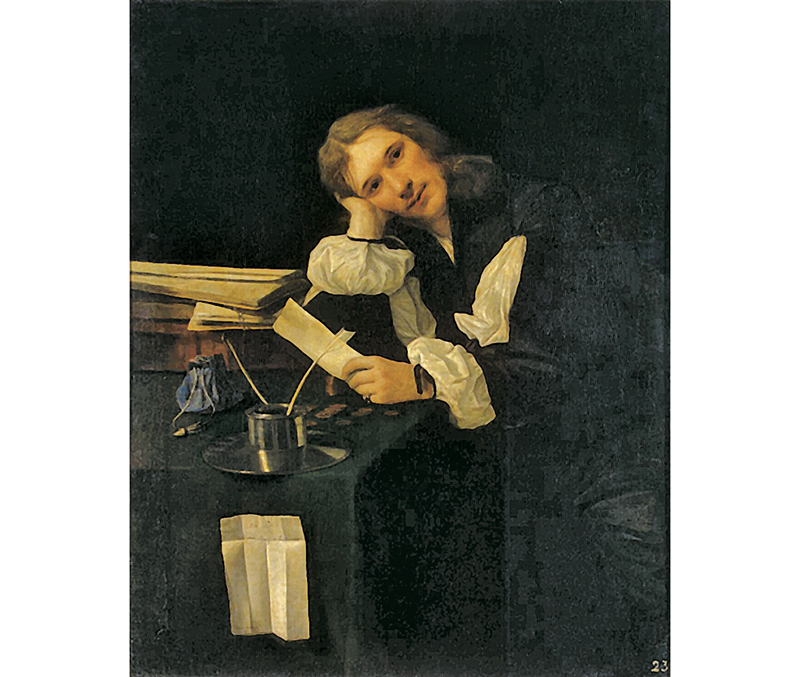

Michael Sweerts, Portrait of a Young Man, 1656 (State Hermitage, St Petersburg)

Sweerts’ paintings, few in number but generally high in quality, span several genres. He left just one work in the grand style: a panoramic view of the plague in a classical city. There are many commissioned portraits of merchant princes. His only series of religious paintings catalogues the Seven Acts of Mercy, while another cycle depicts the five senses. Sweerts excelled at views of life among the common people, following in the footsteps of the Bamboccianti – a group of northerners who specialized in lowlife scenes set in the South. Men cast dice, play cards and smoke pipes, drinkers quaff wine, a ragged workman warms himself at a brazier and an old peasant woman spins thread. A prosperous-looking couple relax in a Roman garden filled with classical statuary. Neapolitan musicians give an impromptu concert, and a grand voyager disembarks. Several paintings show people delousing each other or their clothes.

Handsome men often appear in Sweerts’ works. In one portrait, a beautiful, melancholy young fellow sits at a worktable piled with books and coins, an inkwell and a velvet moneybag before him; a Latin motto warns that every man must give an account of himself. Another shows a debonair gentleman with long russet hair and a red cloak, perhaps the portrait of a Flemish patron. Elsewhere, two Caravaggio-style young men in bright hose play draughts. A man with fine features stands in a shop selling artworks; he looks at a small putto, but an artist or apprentice points him towards a plaster cast of a robust male torso. An Orientalist touch comes in a portrait of a pretty, androgynous youth, sporting a silk turban and holding a nosegay.

Nude or semi-nude men make their way into Sweerts’ scenes. A bare-chested adolescent sits quietly while a mother minds her two young children. A boy in a fez plays cards with a partner, oddly undressed except for a white head-cloth and an indigo wrap around his buttocks. Roman wrestlers encircle each other with strong arms as they joust. One, his creamy back to the viewer, is completely naked; the other, ruddier of hue, wears a demure posing strap. On the sidelines another splendid male specimen, perhaps next in line for a match, raises his hands to pull off a shirt. Spectators abound, a young woman looking outwards with a naughty smile as she witnesses the tussle of male muscle. Kneeling on the ground are two other men, one watching intently, the other stretching his hands in the air, as if moving out of the way or warding off the crowd: images of attraction versus concern.

Manly contact and homoerotic imagery are more brazen in Sweerts’ paintings of bathers. One, completed after his return from Rome but suggesting memories of the South, shows nine men near a pond; one is nearly underwater, with another immersed just far enough so that his buttocks and back become the focal point. Behind them, three nudes lounge stiffly on the bank as river gods. A background figure pulls his shirt over his head. Another, in bourgeois cloak and hat, stares with intent at a tall, slender man next to him, naked except for a loincloth; he looks happy to show himself off as he gesticulates while making some comment to his interlocutor. There is a hint of intimacy, voyeurism and exhibitionism – even homosexual cruising.

The hints become flagrant in the small, dark Young Men Bathing. A group of well-built men congregate around a river at sunset, the last light shining on bodies silhouetted against dense vegetation. Several disport themselves on the shore while others stare at the handsome bathers. The youths resemble classical statues, with well-proportioned physiques and gleaming flesh. A bather raises his hands to wipe his dripping face. Another perches on a rock, stripping off his shirt. Next to him a bare-backed man lowers his trousers, his bottom and genitals exposed with the flair of a strip-tease artiste. He looks towards a bystander, this one wearing cloak and hat, and he returns the gaze of the exhibitionist. Another man sits untying his shoelaces, his head bent at crotch level before the disrobing figure.

Does such a scene reveal homosexual magnetism between the men standing in the shadows and bathers bearing their bodies? One element to suggest this interpretation is the presence in the middle ground of two completely naked men in the shallows, one behind the other, pulling towards him the partner who leans forward, bracing his arms against a tree or a rock. The men could pass for a couple preparing for intercourse. Is this what one art historian brands ‘horseplay’?

No one knows how Sweerts intended his paintings to be seen, and his young blades and lusty swimmers could simply represent academic conventions and scenes of everyday life. The scant contemporary documents about Sweerts record no romantic or sexual affairs, bordello-going, brushes with authorities for sexual misbehaviour, or honest marriage and fatherhood. The scholar Albert Bankert repeats sympathetically the conclusion of Vitale Bloch, an earlier authority, that Sweerts was homosexual – a judgment based on the painting of Roman wrestlers – while Thomas Röske has focused on the homoeroticism of Sweerts’ paintings as an example of ‘queer’ art. Sweerts himself stares out of a self-portrait: immaculately dressed in a black outfit trimmed with brilliant white collar and sleeves, he is a foppish gentleman with long jet-black hair and a carefully trimmed moustache. He wears an enigmatic smile.

‘For thou art all that I can prize

My joy, my life, my rest.’

These lines come from a poem entitled To my Excellent Lucasia, on our Friendship, addressed by Katherine Philips to Anne Owen who, like other members of Philips’ ‘Society of Friendship’, had taken a name inspired by the Classics. Both women were married, but the words bespeak an intense emotional bond that is repeated in other verses. ‘To the dull angry world let’s prove / There’s a Religion in our love,’ she wrote in Friendship’s Mystery, To my Dearest Lucasia; and in a poem on Content, about the pleasures of their intimacy, she declaimed, ‘Then, my Lucasia, we have / Whatever Love can give or crave … / With innocence and perfect friendship fired, / By Vertue joyn’d, and by our Choice retired.’ Lucasia was only one of the women in her circle with whom Philips, or ‘Orinda’, developed such ties. Another poem, for instance, is L’Amitié: To Mrs M. Awbrey, also known as ‘Rosania’: ‘Soule of my soule! My Joy, my crown, my friend!’ The poems describe a mystical, all-giving friendship, a ‘sacred union’ in which all secrets are known and happiness shared, away from the common concerns of the world.

Philips was born in London, the daughter of a Presbyterian merchant (though she later became a keen royalist and supporter of the established church in the struggle between king and parliament). After her father’s death, she moved with her remarried mother to Wales. She herself was married in 1648 – to a husband who sources variously describe as only a few years older than his bride, or more than twenty years her senior – and gave birth to two children, one of whom died in infancy. Philips was well educated, and translated several of Corneille’s plays from French. She succumbed to smallpox on a trip to London in 1664, at the age of 32.

Are her verses lesbian? Philips and her friends were all married, and her poetry bears traces of a lack of interest in the ‘fevers of love’. There is no evidence of physical consummation in the poems, which speak of the rewards of friendship in terms of trust, confidence and communion. Finding lesbians – in the sense of women whose romantic attachment joined with sexual intercourse or who clearly affirmed their physical yearnings for other women – in early modern Europe is very difficult. Some scholars argue that seeing signs of lesbian attraction in Philips’ poetry amounts to a misreading of her work. Claudia A. Limbert, for example, rejects any notion of lesbianism, conceding only that in Philips’ verses the ‘emotional level has been turned up to an almost excruciating pitch’, and claiming that Philips has a ‘spotless sexual reputation’.

Other commentators beg to differ, retorting that the interest women held for other women, especially in Philips’ age, ought not to be seen in narrow terms of genital connection. They stress the importance of women-centred affinities in life and letters, and discover what they suggest are coded erotic references. Harriette Andreadis, for instance, points out that one distinction of Philips’ poetry was that she adapted a platonic but homoerotic language of male friendship to relationships between women.

Andreadis also finds some intriguingly circumstantial biographical details. Philips largely abandoned her friendship with Mary Aubrey (‘Rosania’) after the latter’s marriage in 1652, transferring her affections to Anne Owen (‘Lucasia’). When Owen married and moved to Ireland in 1662, Philips, with the ostensible reason of looking after her husband’s business interests and overseeing the production of her translation of a Corneille play, followed the couple to Dublin. When she returned to Wales, she bemoaned in a letter: ‘I have now no longer any pretence of Business to detain me, and a Storm must not keep me from Antenor [her pseudo-classical name for her husband] and my Duty, lest I raise a greater within. But oh! That there were no Tempests but those of the Sea for me to suffer in parting from my dear Lucasia.’ She continued to suffer grief and disappointment about the separation caused by Owen’s marriage and move: ‘I now see by Experience that one may love too much … I find too there are few Friendships in the World Marriage-proof.’

Andreadis contrasts Philips’ mention of ‘Duty’ in the single extant poem about her husband with the effusive emotions expressed in the many works dedicated to women friends. If, in her poems to Rosania and Lucasia, she had been writing about a man, no one would assume that she was not speaking of romantic and erotic love. After her friend’s marriage, she reacted as a lover scorned. The scholar concludes: ‘There is no question that Katherine Philips produced lesbian texts, that is, texts that are amenable to lesbian reading in the twentieth century.’

Philips’ writing invites continued rereading as sexual or political – as revealed, respectively, by Arlene Stiebel and Graham Hammill. This demonstrates not only the suggestive power of her work, but different academic approaches to female same-sex love in early modern Europe.

Perhaps the last word might be left to a contemporary: Sir Charles Cotterell, the mentor who encouraged Philips’ writing. He pronounced judgment in 1667: ‘We might well have call’d her the English Sappho, she of all the female Poets of former Ages, being for her Verses and her Vertues both, the most highly to be valued’.

Frederick II, the Great, was born in Berlin, the son of Frederick William I and his Hanoverian wife, whose father became George I of England. Frederick William, known as the ‘soldier-king’ and characterized by his son as a ‘severe father and rigid tutor’, has earned a reputation as brutish, interested primarily in military glory, miserly, indifferent to the arts, and an absolutist in politics and in his family life. The young Frederick had the opposite temperament: it was remarked that seldom did father and son less resemble each other. In an autobiographical poem Frederick II would make reference to the Spartan virtues extolled by his father and the ‘gentle manners of Athens’ that beckoned him. His French governess taught him rhetoric, music and poetry, all disciplines depreciated by his father, and he became an ardent Francophile. Frederick displayed a gift for music (even when his disapproving father broke his flutes), and composed dozens of flute sonatas and four symphonies. Architecture was another passion, and towards the end of his reign he would endow Berlin with a series of magnificent buildings.

When he was around 16, Frederick became attached to a younger page boy, Peter Keith (the name testimony to his Scottish ancestry); Frederick’s beloved sister spoke of Keith’s devotion, but let slip, ‘Though I had noticed that he was on more familiar terms with this page than was proper in his position, I did not know how intimate the friendship was.’ An even more intimate friend was Hans von Katte, eight years Frederick’s senior, a nobleman who had studied law and French before entering the Prussian army, where he held the rank of lieutenant. In 1730, Frederick, Katte and Keith devised a plan to flee Prussia for France or England, leaving behind the despotic reign of its king. Their plan was foiled, and they were charged with treason, though Keith managed to escape to Holland. The king ordered Katte to be executed outside the window of the cell where the crown prince was being held: Katte was brought to the window and bowed to Frederick, who extended his hand. The crown prince was so distressed that he fainted as his friend was beheaded. Twelve days later his father finally granted him a reprieve. It will never be known whether Frederick and Katte’s relationship was sexual. It seems that Frederick was in love with him, and his execution was a trauma, perhaps leaving Frederick incapable of an attachment of similar depth.

In 1733 Frederick was forced into marriage by his father; he wrote to his sister that between him and his Austrian bride ‘there can be neither love nor friendship’. In fact, his wife was fond of him, though they never produced children and Frederick generally saw her only once a year.

Frederick’s own reign as monarch, beginning in 1740, provided a change of direction from his father’s rule. He nevertheless proved a heroic military leader, fending off enemies leagued against Prussia and scoring victories in the Seven Years’ War. He dramatically enlarged his realm with the acquisition of Silesia and part of Poland, almost doubling its size. He made significant reforms to the state and the economy, ended torture, allowed freedom of worship and reduced censorship. In so doing, he was putting into practice the ideas of the Enlightenment that had nourished him since his schooldays.

Frederick had long corresponded with the greatest of the philosophes, Voltaire, and in 1750 he invited the French thinker to his residence at Potsdam. The stay lasted almost three years, as Frederick granted Voltaire a court position and comfortable lodgings. Their personal relationship did not always run smooth – Frederick even had Voltaire placed under arrest at one moment – but this was a meeting of minds, the philosopher and the philosopher-king.

After leaving Prussia, a disgruntled Voltaire composed a brief and somewhat scurrilous work on La Vie privée du roi de Prusse (‘The Private Life of the King of Prussia’); it was only published decades later. Voltaire noted that Frederick ‘liked handsome men’ and that he ‘had no vocation for the [second] sex’. The philosopher also recollected the history of Katte’s execution and painted a sketch of a soldier who had befriended the crown prince when he was incarcerated by his father and who remained a faithful companion: ‘This soldier, young, handsome, well built, and who played the flute, managed in more than one way to amuse the prisoner.’ A French minister of the time commented, in jolly versification, that Frederick found the inebriation of amour only in the arms of tambours (drummers).

Anonymous 18th-century portrait of Frederick the Great (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nantes)

Frederick became close to several soldiers, courtiers and other visitors to the grandiose palace of Sanssouci that he constructed, among them the dashing Francesco Algarotti. A bisexual writer and diplomat and a quintessential Enlightenment figure, Algarotti travelled to England (where he had dalliances with Lord John Hervey and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu), France (where he befriended Voltaire) and Prussia. He lived there for eight years, was made a count and court chamberlain, was awarded various decorations and possibly was Frederick’s lover for several years as well. (Voltaire noted, however, that Algarotti was inconstant; spying him hugging a French attaché, he said, ‘I seem to see Socrates reinvigorated on Alcibiades’ back.’)

Frederick commissioned a fresco of Ganymede for his palace, and had his ‘Temple of Friendship’ at Sanssouci ornamented with medallions of classical couples, including Pylades and Orestes, Heracles and Philoctetes, and Pirithous and Theseus. He also penned a verse wondering why St John was taken as the Ganymede of Jesus – a neat linking of homoerotic classical and Christian mythology. The references show the cultural influences that could be used both to hide and to reveal the sexual proclivities of an Enlightenment potentate.

The categories of male and female have provided easy ways to classify biological sex, expected types of behaviour, virtues and sexual desires. Yet transvestites, choosing to dress and act in a manner considered appropriate to the other sex, and transgender people, who feel that they are of one gender but have the body of another, and who may use pharmaceutical or surgical intervention to reassign their gender, blur this division.

Such transgressive behaviour is not new. One 18th-century example of a ‘gender-bender’ is the Chevalier d’Eon. Born in a Burgundian town to a minor royal official and a noblewoman, Charles-Geneviève-Louise-Auguste-André-Timothée d’Eon de Beaumont confesses in a not always trustworthy autobiography that, since his sex was unclear at birth, he was given ‘the names of both male and female saints in order to avoid any error’. Raised as a boy, he received a fine education at an elite Paris school, took a degree in law, and in his mid-twenties published a tome on French finances, the first of fifteen volumes he authored. Intellectual achievement and personal connections brought him to royal attention, and he won appointment to a diplomatic mission to Russia. During the Seven Years’ War, he served as an officer in the dragoons, sustaining injuries in battle, and in 1763 was sent, ultimately with the rank of Minister Plenipotentiary, to London for negotiations on the peace treaty between France and Britain. For his efforts, he received France’s highest decoration, the Order of St Louis. Unknown even to most of the king’s ministers, d’Eon also worked secretly as a spy for Louis XV in London, continuing to send reports back until the monarch’s death in 1774 – intelligence intended for a possible French invasion of the British Isles.

Soon after his arrival in London, to his uncontained anger d’Eon was passed over for appointment as permanent ambassador in England – partly because of official annoyance at his huge expenses (especially the bills for Pinot noir), and partly because his patron had lost favour at court. The foreign minister recalled d’Eon, but he refused to leave London, reminding the king of his secret mission. The conflict between d’Eon and his masters placed the French government in a delicate position – especially since d’Eon was flirting with British radicals – and continued without solution for almost a decade. D’Eon, now deprived of an official post but still gathering intelligence, all the while feuding with the new French ambassador, gave journalists and caricaturists a chance to make merry with depictions of court intrigues and supposed conspiracies.

Around 1770 rumours began to circulate that d’Eon was in fact a woman, adding to his notoriety and leading people to place bets totalling tens of thousands of pounds on his true sex. D’Eon mounted a lawsuit against the wagering, but remained coy about settling the matter. The new scandal made news on both sides of the Channel, until a court emissary worked out an agreement. In return for a pension, d’Eon would return to France as a woman, wear only women’s clothing, relinquish all secret documents and take no further role in politics.

D’Eon went home but made great efforts, in vain, to be allowed to wear the uniform of a dragoon captain, though the king conceded that she could wear the Order of St Louis. Banished from court, d’Eon lived at the family house in Burgundy. Her patroness counselled: ‘If Louis XV armed you as a Knight of French soldiers, Louis XVI arms you as a chevalière of French women.’ Her request to raise a company of women soldiers to fight in the American War of Independence met with refusal.

In 1785, bored with life in rural France and chafing at her treatment by Versailles, the chevalière returned to London, championing the British political system and soon applauding the revolution unfolding at home. She lived as a woman, sharing lodgings chastely with an admiral’s widow. The French no longer paid her pension, and she sold a vast library, then earned money through fencing tournaments, to make ends meet. From the mid-1790s, she lived in virtual seclusion, composing memoirs and religious writings that articulated what her biographer calls ‘Christian feminism’.

At this point of her life d’Eon admitted that she had been born a female and was now happy to assume her true gender. However, when d’Eon died in 1810, her octogenarian housemate discovered, while preparing the body for burial, that d’Eon was biologically a normal male. Physicians confirmed the finding, even though in the 1770s magistrates and doctors had pronounced d’Eon a female.

In a study of d’Eon’s remarkable life, the historian Gary Kates has showed how d’Eon fashioned a persona for himself, and explored the reasons why d’Eon decided to lead the second half of his life as a woman. The change came not from gender confusion or sexual dissidence; d’Eon’s manuscripts and actions betray no trace of psychopathology or of ‘gender identity disorders’. Rather, his metamorphosis was a conscious intellectual decision. Faced with the ruin of a political career, financial difficulties and alienation from French life, d’Eon found in the transformation a way to confront an awkward future. It was, perhaps, d’Eon himself who had planted rumours that he was a woman, although his slight build, absence of facial hair and lack of amorous affairs had already raised eyebrows. Long interested in the status of women – his library included many volumes on the subject – d’Eon made a dramatic, radical life choice. There is, incidentally, no record of any romantic or sexual entanglement with man or woman.

The public greeted the d’Eon affaire with fascination but neither horror nor outrage; d’Eon was never considered a pariah or a freak. As Kates points out, although gender divisions were clearly demarcated in Enlightenment Europe, sex and gender were not considered synonymous. ‘D’Eon’s life’, he adds, ‘was played out against the backdrop of other kinds of gender experiments that tested and challenged relations between the sexes and the nature of manhood and womanhood.’ Writers from Jean-Jacques Rousseau to Mary Wollstonecraft philosophized about upbringing, sexuality and gender. There existed a fluidity in terms of gendered clothing, behaviour and activities. Figures such as William Beckford – known for sexual encounters with young men, and for playing with gender in the novel Vathek – challenged traditional notions. Increasing urbanization and social mobility helped swell the sexual subcultures of cities such as London and Paris, each of which also hosted thousands of prostitutes. In London, ‘molly houses’ provided ample opportunities for men who sought their own sex, where they nevertheless often adopted female names and personae during their merriment. D’Eon was part of this changing culture, even if he constitutes an extraordinary incarnation of its possibilities.

D’Eon’s story has inspired novels, plays, a film, an opera and a Japanese anime series. Moving between countries, professions, dress and gender, d’Eon occupied various interstices of Enlightenment life, thwarting gender assignment by jurists and doctors, rejecting easy categorization by contemporaries and historians, and engaging in impressive self-fashioning. A suitable epitaph comes from d’Eon’s autobiography: ‘For I who have neither husband, nor master, nor mistress, I would like to enjoy the privilege of obeying only myself and good sense.’