In the pantheon of great gays, Walt Whitman certainly ranks, alongside Oscar Wilde, as one of the most famous and most influential figures. After the two met in 1882, Wilde said of Whitman: ‘He is the grandest man I have ever seen. The simplest, most natural, and strongest character I have ever met in my life. I regard him as one of those wonderful, large, entire men who might have lived in any age, and is not peculiar to any one people. Strong, true, and perfectly sane: the closest approach to the Greek we have yet had in modern times. Probably he is dreadfully misunderstood.’ The differences between the two are great – the cosmopolitan British dandy, the rather rustic and proudly simple American – and they typify varying 19th-century attitudes towards homosexuality. Despite a common harking back to antiquity, one approach drew its inspiration from the traditions of the Victorian metropolis, while the other was rooted in a new-world sense of democracy, egalitarianism and camaraderie. They bequeathed these strands of homosexual culture to the next century.

The New York poet, in his life and writings, provided great inspiration for homosexuals in America and overseas. Edward Carpenter (who visited Whitman in America, and intimated that their meeting included a sexual encounter), André Gide, Yukio Mishima and many others invoked his name as kindred spirit and precursor. Later homosexuals named after him a long-lived gay bookshop in Manhattan. Yet Whitman had such broad resonance throughout American culture that he became a national hero, the nation’s poet; the more conservative of his admirers carefully bowdlerized sexual passages in his writing and passed over his homosexuality as they christened streets, schools and other public institutions in his memory. Many who heard in Whitman’s verses the authentic voice of the American would have been – and may still be – horrified to think of him as a sodomite.

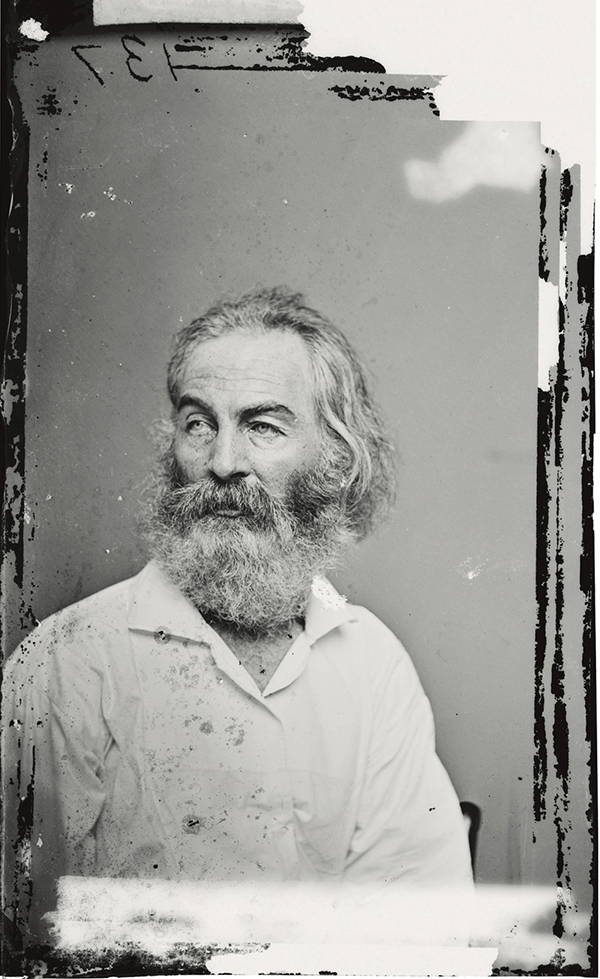

Walt Whitman, c. 1860 (Brady-Handy Photograph Collection/Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

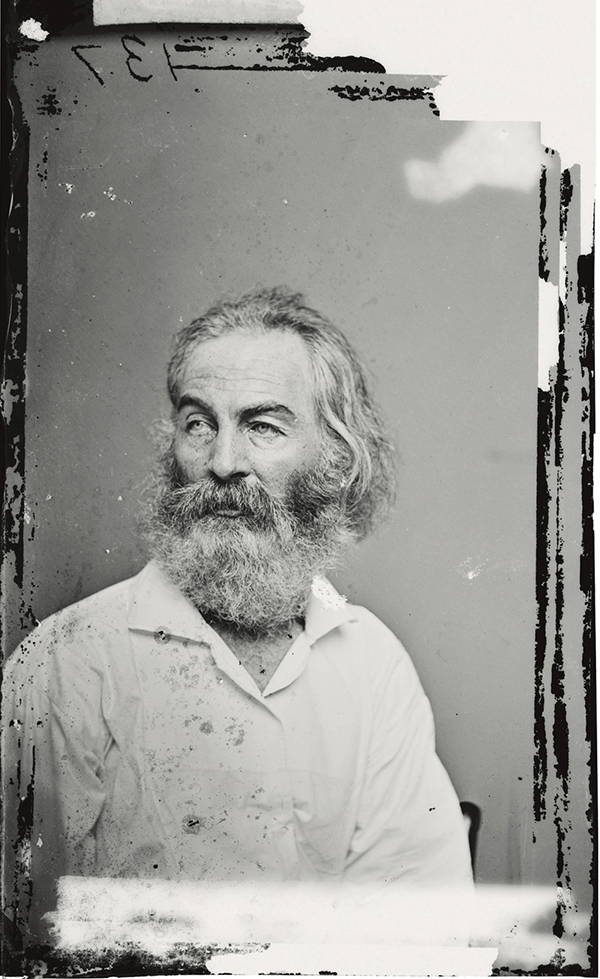

Walt Whitman and Pete Doyle, Washington, D.C., 1865 (Feinberg-Whitman Collection/Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

Reading Whitman’s work today, it is difficult to believe that anyone could have ignored its homoerotic aspects. In ‘Song of Myself’, he confesses to ‘the hugging and loving bed-fellow [who] sleeps at my side through the night’, and he enjoins a friend to ‘Undrape! You are not guilty to me …’. A single stanza of exaltation merges a man’s body with the landscape, the ‘firm masculine colter’, ‘beard, brawn’, ‘fibre of manly wheat’, ‘broad muscular fields’ and ‘your milky stream’. Certain scholars find even more blatant references to sexual acts coded into his words. In the ‘Calamus’ poems of the 1860s, Whitman’s statements are particularly bold as he describes the ‘adhesiveness’ of comradely love: ‘I am the new husband and the comrade’, he declares to a friend, inviting him to commune ‘if you will, thrusting me beneath your clothing, / Where I may feel the throbs of your heart or rest upon your hip’. In another poem, he recalls a night spent with ‘my dear friend my lover’: ‘In the stillness in the autumn moonbeams his face was inclined toward me, / And his arm lay lightly around my breast – and that night I was happy’.

Whitman’s writing exudes joy at intimate friendship. ‘I myself am capable of loving’, he affirms, holding aloft a phallic calamus root as a token of his desires. As a greybeard, he takes pleasure in the kiss of a young man, and finds supreme contentment just in a friend’s simply holding his hand; he recollects with sad fondness a departed one who is yet never separated from him. And in ‘Among the Multitude’, he spies the ‘lover and true equal’ who is his heart’s ideal.

The self-styled ‘poet of comrades’ fashioned a vision of manly love between friends that would be the leaven for a new age and a new spirit, embedded in the nature that Whitman evoked – the busy life of Manhattan, the quiet of the prairies, the earthy smells of the soil. ‘COME, I will make the continent indissoluble, / I will make the most splendid race the sun ever yet shone upon, / I will make divine magnetic lands, / With the love of comrades, / With the life-long love of comrades.’ There is utopianism in Whitman’s work, a great communitarian vision of society as eroticized companionship writ large, built on the adhesion of individuals.

Singing of himself, a prophet of personal and political liberty within this desired comradely cosmos, Whitman’s verse also bespeaks refusal of norms, a rejection of social expectations. Musing in ‘As I Lay with My Head in Your Lap, Camerado’, he challenges: ‘I confront peace, security, and all the settled laws, to unsettle them; / I am more resolute because all have denied me, than I could ever have been had all accepted me; / I heed not, and have never heeded, either experience, cautions, majorities, nor ridicule.’ Elsewhere, he declaims: ‘I am the sworn poet of every dauntless rebel the world over.’ Here is a confession of difference, and a manifesto for action: no wonder Whitman’s voice echoed for later generations of activists.

Whitman was born on Long Island, in New York, in very modest circumstances, and grew up in the borough of Brooklyn. He received only a simple formal education, though his work testifies to interest in literature, opera and history. He worked in various jobs, from apprenticing as a compositor and editor in a printing office to schoolteaching and journalism. He held several posts in the civil service, losing one position in the Department of the Interior because his boss considered his collection of poems Leaves of Grass, first published in 1855, to be obscene (the book was banned in certain American cities). During the Civil War he went to Washington, where he worked as a volunteer in Union hospitals, the war service and his frequenting of the young soldiers (such as the ‘Tan-Faced Prairie-Boy’ of one poem) leaving a lasting impression. The assassination of the greatly admired Abraham Lincoln also much affected him and inspired poems in his memory.

Whitman formed ‘adhesive’ relations with several young men. The most significant of his partners was Peter Doyle, a bus conductor, whom he met in 1866: ‘We were familiar at once – I put my hand on his knee – we understood. He did not get out at the end of the trip – in fact went all the way back with me,’ Doyle remembered. A series of letters that Whitman wrote to ‘dear boy Pete’ from 1868 to 1880, full of expressions of affection, recounted Whitman’s daily life, commented on political developments, and proffered fatherly advice to his protégé.

Some aspects of Whitman’s poetry jar with present-day readers – the utopianism, a naïve American boosterism, a stylistic tendency to catalogues of places or allusions. Yet in his transcendental (and now, as we see it, very ecological) appreciation of landscape, his pleasure in friendship and love, his celebration of unbounded sexuality, his taking up of the cause of the outcast (in, for instance, a poem addressed ‘To a Common Prostitute’), and his rejection of the dictates of God and religion, the patriarchal Whitman remains a profoundly modern bard.

More than eight decades after his death, Edward Carpenter seems a remarkably contemporary figure – all the more so now that his ‘life of liberty and love’ has been newly chronicled in a biography by Sheila Rowbotham. Although his understanding of homosexuals – or ‘Urnings’, as he termed them – as an intermediate sex is now antiquated, and some of his views appear quaintly utopian, his presence remains strong. An advocate of manly ‘homogenic love’ in theory and practice; an apostle of a simple, proto-environmentalist life; a promoter of socialist democracy; a spokesman for women’s rights; a scholar of international gay cultures – Carpenter was broad and sympathetic in his reach.

Born in Brighton to a former naval commander turned barrister and successful railway investor, and a mother who looked after her large family (he was one of ten children), Carpenter was educated at Trinity Hall, Cambridge. After finishing his undergraduate studies, he was elected to a fellowship at his college and ordained as an Anglican minister. Within a few years, however, he had lost his faith, and in 1874 resigned religious orders and his fellowship. He moved to the north of England, to take up a position in a newly created university extension scheme for the education of workers and women. In 1880 he found lodgings with a scythe-maker named Albert Fearnehough, who, though married, became Carpenter’s lover.

Several encounters proved particularly significant for Carpenter, but none more so than his friendship with Walt Whitman, who was his lodestar. Carpenter had written in admiration to the poet in 1874, and in 1877 he visited him in New York; a second trip a few years later confirmed their deep affinities. Leaves of Grass provided a model for Carpenter’s book-length poem Towards Democracy, first published in 1883 and later expanded; and Whitman’s ideas about an egalitarian, mutually supportive attachment between men – spiritual, emotional and physical – formed the basis of Carpenter’s notions of homogenic love. Whitman’s influence is also clear in Carpenter’s writings on homosexuality. These took the form of a privately printed pamphlet later reissued as Love’s Coming of Age (1896) – his courage in addressing the subject at the time of the Oscar Wilde affair is remarkable – and The Intermediate Sex of 1906. The works constitute the first straightforward defence of homosexuality in Britain.

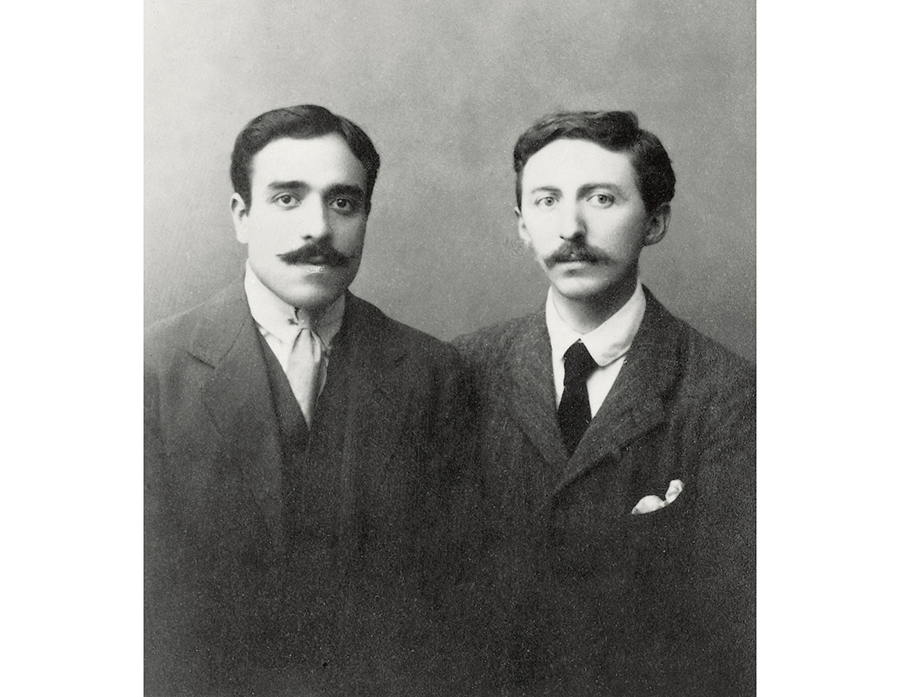

Edward Carpenter and George Merrill at Millthorpe, c. 1900 (Sheffield City Council, Libraries Archives and Information: Sheffield Archives [Carpenter/Box 8/50])

While still at Cambridge, Carpenter had met Ponnabalam Arunachalam, a student from Ceylon. They became good friends (though, it seems, not lovers), and Arunachalam, later both a highly placed colonial civil servant and an early nationalist leader, introduced Carpenter to the Bhagavad Gita and other classic Indian texts – sparking an interest in Eastern philosophies that endured. Carpenter visited Arunachalam in 1890–91, and his journey to Ceylon and India, chronicled in From Adam’s Peak to Elephanta, proved a grand experience, for the attractive exoticism of the landscapes, religions and culture, as well as for the beauty of the young men. Carpenter came back with firm opinions about the wrongs of colonialism. The two friends also conversed about sexuality in Asia: a posthumous publication brought together some of their writings on the subject, and in 1914 Carpenter published a book on Intermediate Types among Primitive Folk, an explanation of same-sex traditions in the classical world, among native peoples, and in the Japanese samurai caste.

Soon after his return from Asia, in a chance encounter in a railway carriage, Carpenter met an unemployed 20-year-old from the Sheffield slums, George Merrill. They began an affair, and Merrill moved into the farm, Millthorpe, that Carpenter had bought in Derbyshire. They remained together until Merrill’s death in 1928, one year before Carpenter himself died. (The two are buried together in Guildford, Surrey.) Merrill was the ideal partner, and Carpenter felt that such an attachment as his own, between someone from the working classes and another from the middle classes, could help breach the enormous social and cultural divides that he considered one of the evils of European society.

Carpenter and Merrill pursued an intentionally simple life at Millthorpe, engaged in what Carpenter termed the ‘exfoliation’ of unnecessary layers of social practice. They did not eat meat or drink alcohol, wore plain clothes (with sandals something of a fashion fetish), and supported William Morris’s artisan-based Arts and Crafts movement. Carpenter took an active role in the Progressive Association, the Sheffield Socialist Society, the Fabian Society, the Humanitarian League (which campaigned against blood sports and vivisection), the anti-war movement at the time of the Great War, and the British Society for the Study of Sex Psychology, which he helped to found in 1913. Alongside these other activities, he continued to write: a mischievously titled book on Civilization: Its Cause and Cure; a memoir about Whitman; and a collection of homogenic poetry through the ages, called Ioläus: An Anthology of Friendship, to name but three. His writings, and those of his interlocutors John Addington Symonds and Havelock Ellis, articulated an apologia for homosexual life and rights. Carpenter became a well-known figure for disciples of the ‘counter-culture’ (though the term is anachronistic) and for homosexuals, and his house a place of pilgrimage for such men as E. M. Forster, who sought his wisdom and his encouragement.

André Gide was one of the towering cultural figures of the first half of the 20th century. That he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1947 is only one of the attestations to his place in the modern pantheon. He typified some of the swirling currents of his lifetime. Born into comfortable circumstances, the son of a professor of law, he pushed against the boundaries of social conventions. Like many people, he wrestled with religion (in his case, the Protestant beliefs that he ultimately jettisoned). He dabbled with Communism, a creed he rejected after a visit to the Soviet Union. He journeyed to equatorial Africa to witness France’s mission civilisatrice, and returned to write a searing critique of colonialism. He moved in the hothouse world of the Parisian intelligentsia, adopting and contributing to the ideas and styles of modernism. His sexual horizons were broad: he was married (though the union was almost certainly unconsummated) and the father of a child by another woman, but he also was one of the best-known homosexuals of his time.

Homosexuality appears in much of Gide’s life – he claimed a number of young disciples and lovers, from young street-boys and peasants he met in Algeria and Egypt to gifted French protégés. Homosexuality also appears regularly in his protean writings. His own homosexual initiation in the Maghreb is recounted in the autobiographical Si le grain ne meurt (1924) and fictionalized in L’Immoraliste (1902).

Two works can be taken to represent Gide’s perspectives on homosexuality. Written in 1911, Corydon earned canonical status as an apologia for same-sex desire. A few copies were privately published and distributed to friends by Gide, but the book did not publicly appear until 1920 – itself an indication of Gide’s concern (or his friends’ fear, as he noted in the preface) about its likely impact on his reputation. The book is a set of imagined dialogues between a homosexual doctor, Corydon (who takes his name from one of Virgil’s shepherd lovers), and a rather homophobic narrator. Corydon tries to develop a theory about homosexuality in nature, attributing its existence to a surfeit of males and an over-abundance of male sexual urges, and drawing a distinction between ‘normal’ (that is, masculine) and effeminate homosexuals.

The argument is hardly convincing, and Gide was no scientist, but the couching of the debate in scientific terms relates it to other diagnostic efforts to explain homosexuality as the biological phenomenon of a ‘third sex’, as an arrested stage of psychosexual development, or (much later) as the product of a ‘gay gene’. But setting aside the dubiousness of Gide’s theory and its tedious and pedantic exposition, the importance of Corydon lay in positing homosexuality as a natural thing, a result of nature, and present even in the animal world; it is therefore not, as the moralists argued, contra naturam. Gide’s book also adduces the ancients as evidence of the social benefits of homosexuality, suggesting (as did many later apologists) a link between homosexuality and creativity, and between sex and art. Finally, he refers to many of the prominent homosexual figures and scandals of the modern world – Whitman and Wilde, Sir Hector Macdonald’s suicide and the Krupp scandal in Germany. For all its flaws, therefore, Corydon remains a historically significant commentary on medical, historical, aesthetic and contemporary debates on homosexuality, and a bravely straightforward statement by a homosexual mandarin.

In 1907 Gide wrote Le Ramier, less than twelve pages long in the published version, which did not appear until 2002. It recounts one late July night in the south-west of France, where Gide celebrated a village festival and the election to local government of his friend Eugène Rouart, the engineer son of a wealthy industrialist, and a future senator. On this evening, Gide made the acquaintance of the handsome son of a farm worker, Ferdinand, a 17-year-old (though Gide erroneously said he was 15). After the fireworks and dancing, they walk together, and Gide’s flirtation and caresses meet with a mixture of bashfulness and eagerness on Ferdinand’s part. They end up in Gide’s bedroom, the windows thrown open to the summer breezes. Their lovemaking is simple. Gide describes his extraordinary happiness in lyrical prose that captures both the moments of pleasure and his recollection of them. The encounter reminded him of earlier assignations, one with Luigi in Rome, and one with Mohammed, a young man introduced to him by Oscar Wilde in North Africa. Here the scene is the French countryside, the partner is a peasant lad, the sentiments evoked are pure and natural – Gide nicknames Ferdinand the ‘wood-dove’ for the cooing sound he makes during their embraces.

Gide’s short piece is rich in details: his attraction to ephebes; Rouart’s apparent cultivation of a whole flock of young partners; the sense of complicity between the two men; Ferdinand’s pretensions to sexual experience and knowledge, contrasted with his manifest innocence; his ardour and willingness to engage in sexual relations with a man twenty years his senior, though without declaring himself homosexual. Rouart later had his own intimate encounters with Ferdinand, and even planned, as he told Gide, to write a novel about the young man. But Ferdinand succumbed to tuberculosis and was confined to hospital, where Rouart visited him, keeping Gide informed of his illness until the boy’s death in 1910.

Corydon and Le Ramier record theory and practice, the intellectual and the emotional experience of homosexual attachment, a debate in a Paris drawing-room and a chance encounter in the French countryside, an attempt to grasp the condition of the homosexual as a species and the memorialization of a particular type of desire and its satisfaction. Today Gide may seem somewhat fusty, his theories outmoded and his encounters tentative and coy, but in his own day he was a sexual and literary revolutionary.

When Edward Morgan Forster was born, Queen Victoria still had more than two decades to reign; when he died, Queen Elizabeth had been on the throne for almost twenty years. In 1879 a man convicted of buggery could still be punished under English law with life imprisonment: only three years before Forster’s death did Parliament hesitatingly and incompletely repeal laws that made consensual homosexual acts a crime.

E. M. Forster with Syed Ross Masood, 1911 (King’s College, Cambridge)

Forster lived through the Wilde affair of the 1890s, offered to testify on behalf of Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness when it was declared obscene in 1928, and followed with concern a homosexual scandal of the 1950s involving several English gentlemen arrested for public indecency. He met Edward Carpenter in 1912, negotiated the complex sexual relationships of the Bloomsbury set in the years around the First World War and, from a distance, witnessed the beginnings of gay liberation in the 1960s.

The convoluted sexual history of British society helps readers understand the pattern underlying both Forster’s long private life and his writings. Shortly before his death, speaking to a potential ‘official’ biographer, William Plomer, Forster emphasized his attitude towards his sexual experiences and their importance: ‘M[organ] said he wanted it made clear that H[omosexuality] “had worked”.’ The centrality of homosexuality to Forster’s life and work is not a topic that all commentators have highlighted, although one recent biography, by Wendy Moffatt, is noteworthy for giving it due place.

Forster was a product of the Victorian middle class. His father, who died when Forster was a child, was an architect. His mother was a headstrong and cloying companion with whom he shared a house and who dominated Forster until her death in 1945 – a major reason for his lack of public openness about his homosexuality. Forster studied at King’s College, Cambridge, between 1897 and 1901, returning as a fellow for his last twenty years. He lived by writing, eventually amassing enough wealth to fund his generosity to friends and protégés. His friends encompassed a Who’s Who of the cultural aristocracy of his day, including many of a homosexual disposition. Among early acquaintances were Virginia Woolf, Lytton Strachey, Duncan Grant and John Maynard Keynes, and Forster later became a mentor to Christopher Isherwood, who received the unpublished manuscript of Maurice, his gay-themed novel, after his death. Though shy and awkward, Forster claimed many great figures as his admirers. He received fame and honours: he was awarded the Order of Merit, was made a Companion of Honour, and was offered a knighthood, which he declined.

Forster’s romantic and sexual passions were not for those who shared his background. (He told Plomer it was important for biographers to note that ‘none of his intimates had been eminent’.) Forster’s sexual apprenticeship had been long and painful. He really had no sexual experience as a young man, not even the erotic horseplay of adolescents. At Cambridge he fell in love with a fellow student, Hugh Meredith, and a few years later met Syed Ross Masood, a robustly handsome, debonair Muslim from a grand Indian family who was studying in England. Masood returned his affections – although not sexually – and Forster considered him his closest friend for many years afterwards. They remained correspondents when Masood returned to India, and after Masood’s death his children continued to visit Forster in England.

Forster’s real sexual initiation came in Alexandria, where he had gone in 1915 to serve with the Red Cross during the First World War. This experience took the form of a quick encounter with a soldier on the beach, but Forster soon met a striking young tram conductor, Mohammed el-Adl. Despite their social and cultural differences, they drew closer and entered into a sexual relationship – Forster’s first consummated affair. Forster was in love, but the end of the war spelled the end of his sojourn in Alexandria. He remained in contact with el-Adl, just as he had with Masood (in whom he confided about his Alexandrian romance). El-Adl married, fathered a child – whom he named Morgan – and saw Forster again when the writer travelled through Egypt on his way to India to visit Masood. El-Adl died from tuberculosis, in 1922, while still in his twenties. Forster never forgot him, carefully preserving his letters – the final messages from Mohammed, with ‘I love you’ repeated in a shaky hand, remained powerful mementos – and each year on the anniversary of his death he put on a ring that el-Adl had given him.

By the time he returned to England, in 1919, Forster was sexually freer, and in the middle of the 1920s estimated that he had had sex with the respectable number of eighteen men. Others relationships followed, sometimes simultaneously, and always with men from the working classes. The most important was with Bob Buckingham, a police officer who was Forster’s lover for years, and occasionally slept with him even after his marriage. Buckingham and his wife proved Forster’s most loyal companions in his later years.

Homosexuality makes only veiled appearances in Forster’s early published writing. However, he intimated that he stopped producing novels after the 1920s because social disapproval meant he could not treat the topic that was central for him. The last novel to appear in his lifetime, A Passage to India (1924), provides perhaps the clearest portrayal of a bond between two men, an Englishman and an Indian – a relationship doomed by colonialism and mores, possible (in Forster’s poignant phrase) ‘not yet … not there’. The book, dedicated to Masood, drew on Forster’s own rather rocambolesque adventures as a short-term secretary to a maharajah in the 1920s, and spoke deeply of his love of India and his discord with the tenets of British colonialism.

Forster wrote his gay-themed novel, Maurice, before the First World War, and occasionally showed it to friends, but considered the manuscript unpublishable. The story, of a relationship between a stockbroker and a gamekeeper – ‘ordinary affectionate men’ – now seems sentimental and dated, but it perfectly captures the homosexual mood of its time and place. Forster was determined that his sole true novel about homosexuality should have a happy ending. After his death, the publication of Maurice (1971) and of a sheaf of short stories with homosexual themes written over the years focused attention on the gay aspects of his life and his other literary works.

Forster’s writings and loves reveal ways in which a homosexual man could ‘connect’ (to ‘connect’ intellectually, emotionally and in other ways was the hallowed directive of the Bloomsbury Group) across boundaries of social status and race, and even across the boundary between homosexual and heterosexual. Though he felt constrained by law, family pressure and the regard of society, Forster illustrated the many fashions in which gay lives could be constructed and sexual desires moulded – from the common rooms of Cambridge to the London suburbs, from England to the Italy and America that figure in his travels and stories, and on to Egypt and India. It is not surprising that literary critics, biographers, historians and readers return time and again to his works.

Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness is the most important lesbian work in modern literature. Today her view of lesbianism as ‘inversion’ – a common conclusion in the early 1900s – is no longer credible, and the book’s somewhat overwrought writing and dark ending hardly make it a joyful read. For decades after its publication in 1928, however, the novel provided one of the few forthright and affirmative depictions of love between women, and thus exerted enormous influence internationally. The daring nature of Hall’s work is also significant. The British government banned it as obscene: despite the support of many literary luminaries, it was not again on sale in the United Kingdom until after the Second World War.

The Well of Loneliness tells the story of Stephen Gordon, a provincial woman from the upper classes (given her first name by a father who had hoped for a boy) who shows no interest in men as companions or suitors, or in typically feminine pursuits, but is drawn to manly activities such as hunting and fencing. She struggles to establish her identity, takes to wearing men’s clothing, reads about sexuality in her father’s library, and falls scandalously in love with a woman neighbour, declaring the nobility of her love when her family discovers her sentiments. She moves to London to write novels, then travels to Paris and discovers a lesbian coterie in the French capital. As an ambulance driver in the First World War, she meets and falls in love with another woman, Mary Llewelyn; Gordon eventually gives her up to a man, however, which seems the only way to secure for Mary the happiness that she herself cannot provide. The book concludes with Gordon’s plea for recognition: ‘God, we believe … Acknowledge us, oh God, before the whole world. Give us also the right to our existence!’

Various aspects of the novel, if not the exact plot, mirror Hall’s own life. She was born into a prosperous family in Bournemouth, but her parents separated when she was very young. Her childhood was not entirely happy: she did not get along with either her mother or her stepfather, who may have abused her, though her beloved grandmother provided comfort. Hall was educated privately, as was usual for girls of her background, and went on to study briefly at King’s College London and in Dresden. At the age of 21 she inherited a fortune (the equivalent of many millions of pounds in present-day terms) from her grandfather, who had been a physician, sanatorium-owner, magistrate and alderman.

Hall, or ‘John’, as she was later known to her friends, had her first lesbian infatuations and affairs as a young woman, and did not doubt that she had been born an ‘invert’. She was well versed in the sexological theories of the early 20th century, including the writings of Havelock Ellis, who contributed a foreword to The Well of Loneliness. Such theorists explained homosexuality as ‘congenital’: some people felt the emotions and desires of one sex while trapped in the body of another. Homosexual desires were, therefore, natural to them, though society generally took the opposite view. Homosexual men and women, they argued, were often drawn to mannerisms and styles of dress (for example) more common to the other gender. Photographs of Hall, who was always elegant, show her attired in Savile Row-tailored masculine suits and in hats of the sort sported by Stephen Gordon in her novel.

In 1907, when she was 27 years old, Hall fell in love with the 50-year-old Mabel Batten, known as ‘Ladye’, whom she had met at a spa resort in Germany. The daughter of the British Judge Advocate General of India, Batten was a fashionable singer and a pianist. She was married and had children and grandchildren, but after her husband’s death, in 1911, she moved in with Hall. Batten was a Roman Catholic, and the following year Hall converted, and was soon received by the pope during a trip to Rome; she never saw a contradiction between her sexuality and her religion, or between Catholicism and an interest in spiritualism.

Through Ladye, in 1915 Hall met her cousin Lady Una Troubridge. Margot Taylor, who owed her married name and title to an ageing admiral, was a Royal Academy-trained sculptor, singer and translator. She and Hall began an affair, and after Batten’s death in 1916 – and Troubridge’s separation from her husband – they starting living together as partners, in a relationship that lasted almost thirty years. They divided their time between London residences and Paris, which they increasingly preferred after the obscenity trial connected with The Well of Loneliness. There and in London, Hall made friends with many of the prominent lesbian figures of her day, from Ethel Smyth to Natalie Clifford Barney (on whom one of the main characters in The Well of Loneliness was modelled). Late in life Hall had one further relationship, with Evguenia Souline, a White Russian nurse whom she had engaged to care for the ailing Troubridge. After Hall’s death in 1943, Troubridge, who lived for a further twenty years, wrote a memoir detailing their life together. Hall and Batten are buried in the same vault in Highgate Cemetery, London; Troubridge died in Rome and was buried there, her tombstone describing her as ‘the friend of Radclyffe Hall’.

By the time of the First World War, Hall had published half a dozen well-received volumes of poetry. Yet where her novels are concerned, The Well of Loneliness has overshadowed all her other works, including Adam’s Breed (1926) – the story of a misfit among a group of Italian migrants in Soho that won literary awards in both Britain and France. The early novel with the most overtly lesbian theme is The Unlit Lamp (1924), in which a girl falls in love with her female tutor, a learned and assertive ‘New Woman’; she proves incapable of realizing her desires, however, caught between family obligations and her lack of resolve, and ends up defeated and unfulfilled. Most of Hall’s work, except for The Well of Loneliness, is now out of print.

Christopher Isherwood 1904–1986

Christopher Isherwood had three lives. His first, and most formative, was that of an English gentleman born in the Edwardian age. The second – as an expatriate in early 1930s Berlin – provided experiences that made him and his writing famous. His third, and longest, life, covering almost five decades, saw him settled in the United States as an acclaimed author, a student of Hinduism and a California celebrity.

Isherwood was born into the upper-middle class, his father a lieutenant-colonel killed in the battle of Ypres in 1915, his mother from a family of wine merchants. At Repton, a venerable independent school, he met W. H. Auden, a life-long friend, literary collaborator and sometime lover. Isherwood read history at Cambridge, but intentionally failed his tripos examinations – writing humorous and facetious answers – which resulted in his expulsion in 1925 and put paid to his mother’s hope that he would become a don. Enrolment to study medicine in London was an even more abbreviated encounter with academia. In the meantime Isherwood was involved in a sustained relationship with the violinist André Mangeot and was working on his first novel, All the Conspirators, published in 1928.

Auden had gone to live in Berlin in the late 1920s, attracted by Europe’s most dynamic gay life, which included numerous bars and cabarets, Magnus Hirschfeld’s sexology institute, and readily available men. He encouraged Isherwood (and Stephen Spender, the third in the triangle of literary comrades) to follow, and so he did. ‘To Christopher, Berlin meant Boys,’ Isherwood wrote neatly in his autobiography. Weimar Germany provided a liberation from interwar England, and Isherwood indulged happily in its pleasures, ultimately falling in love with a young man named Heinz Neddermeyer, the type of rough diamond extracted from the working class to whom he felt attracted. On the horizon, however, was Nazism, and Isherwood’s novels Mr Norris Changes Trains (1935) and Goodbye to Berlin (1939) deftly capture the oncoming menace that would bring the ‘divine decadence’ to an end. The novels scored an enormous success, and the works were eventually transformed into a play, a musical, and then, in 1972, the movie Cabaret. That film – with the handsome Michael York perfectly playing Isherwood, and Liza Minnelli singing memorable songs with more talent than the real chanteuse that she incarnated – is arguably the most popular gay-themed movie ever made, even if the gay adventures of Isherwood form only part of the plot.

The rise of Nazism forced expatriates such as Isherwood out of Germany. Isherwood and Neddermeyer went first to Greece, though the ruin-strewn land of antiquity so seductive to other homosexuals held little magic for men nostalgic for the boulevards of Berlin. England, too, proved uncongenial, and the Canaries provided only an interlude, since Neddermeyer was obliged to return to Germany, where in 1937 he was arrested for committing sexual offences and avoiding military service. Separated from his partner, the following year Isherwood went to the Far East with Auden, writing Journey to a War (1939) about their travels during the Sino-Japanese conflict.

In 1939 Isherwood, along with Auden, arrived in America as a refugee from a Europe on the verge of war. He settled in sunny southern California, as did many other expatriates. Isherwood adapted rapidly to American life, earning money as a scriptwriter and finding easy sexual contacts. He became keenly interested in the Indian Vedanta religion and philosophy, and retreated to a monastery set up by Swami Prabhavananda. They worked together on translations of the Bhagavad Gita and other texts, and Isherwood continued to study the scriptures, though without converting to Hinduism, after he left the monastery, confessing that sexual abstinence proved impossible.

In 1953, on a beach in Santa Monica, Isherwood met Don Bachardy, an attractive 16-year-old. Two years later they began an affair – a love story that lasted, despite the thirty-year age difference and occasional difficulties, for the rest of Isherwood’s life. Isherwood nourished Bachardy’s interest in art: after four years of study at art school, Bachardy developed great skill as a portrait painter and held his first one-man show, at the Redfern Gallery in London, in 1961. Over the years, Bachardy painted and drew (and continues to do so) countless portraits of the famous actors and writers who were the couple’s friends, handsome young men who disported themselves around Hollywood and on the beaches of the Pacific, and those who commissioned his work. His favourite subject, however, was Isherwood, whose many portraits lovingly show him through the decades.

Isherwood appears as a key figure in his own works, from his autobiographical writings and Berlin stories (produced in the 1930s and long afterwards) to books about his parents and his guru. His life is also reflected in A Single Man, published in 1964. A story primarily about middle age (according to Isherwood), it centres on an academic trying to remake his world after the death of his lover. Isherwood wrote the novel when he and Bachardy were going through a rough patch in their relationship, and he was imagining what life would be like without his long-time partner. The 2009 film adaptation has done much to revive interest in Isherwood’s writings, and in a life that is uncommonly revealing about experiences of homosexuality over much of the 20th century.